Abstract

Background

The emergence of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa is one of the most important challenges in a healthcare setting. The aim of this study is double-locus sequence typing (DLST) typing of blaNDM-1 positive P. aeruginosa isolates.

Methods

Twenty-nine blaNDM-1 positive isolates were collected during three years of study from different cities in Iran. Modified hodge test (MHT), double-disk synergy test (DDST) and double-disk potentiation test (DDPT) was performed for detection of carbapenemase and metallo-beta-lactamase (MBL) producing blaNDM-1 positive P. aeruginosa isolates. The antibiotic resistance genes were considered by PCR method. Clonal relationship of blaNDM-1 positive was also characterized using DLST method.

Results

Antibiotic susceptibility pattern showed that all isolates were resistant to imipenem and ertapenem. DDST and DDPT revealed that 15/29 (51.8%) and 26 (89.7%) of blaNDM-1 positive isolates were MBL producing isolates, respectively. The presence of blaOXA-10, blaVIM-2, blaIMP-1 and blaSPM genes were detected in 86.2%, 41.4%, 34.5% and 3.5% isolates, respectively. DLST typing results revealed the main cluster were DLST 25-11 with 13 infected or colonized patients.

Conclusions

The presence of blaNDM-1 gene with other MBLs encoding genes in P. aeruginosa is a potential challenge in the treatment of microorganism infections. DLST showed partial diversity among 29 blaNDM-1 positive isolates.

Keywords: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, blaNDM-1, DLST, MHT, MBL

Background

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is one of the most important hospital-acquired pathogens that causes miscellaneous opportunistic infections [1]. The emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR: was defined as acquired non-susceptibility to at least one agent in three or more antimicrobial categories) and extremely drug resistant (XDR: was defined as non-susceptibility to at least one agent in all but two or fewer antimicrobial categories) P. aeruginosa isolates has been considered as a major concern for the treatment of infections caused by these isolates [2]. Carbapenemases are a wide spectrum group of beta-lactamase which hydrolyzes carbapenems to other b-lactams including monobactams, penicillins, and cephalosporins. Although carbapenems are a commonly last resort treatment used for MDR P. aeruginosa infection, the emergence of carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa is becoming a main public health concern and is associated with high rates of mortality and morbidity among hospitalized patients [3, 4].

Resistance to carbapenems can be related to producing carbapenemase enzymes such as serine carbapenemases and the MBLs encoding genes such as IMP, VIM, and NDM enzymes [5]. The MBLs encoding genes such as blaVIM and blaIMP are one of the most clinically important classes of beta-lactamases; but, discovered transmissible New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase-1 (NDM-1) is becoming the most threatening carbapenemase, recently [6–8]. The blaNDM-1 producing strains are resistant to a wide-ranging of other antibiotic groups and transport numerous additional resistance genes such as genes encodings resistance to fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, sulfonamides, and macrolides. Furthermore, the NDM‑1 enzyme is surfacing, resulting in almost whole resistance to antibiotics [8–10].

Molecular typing of P. aeruginosa is important to understand the local epidemiology, but it remains a challenging issue. The epidemiology of P. aeruginosa has been analyzed by an array of different typing methods such as Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) that are costly, required specific technical abilities and time to consume [11]. The newly described double-locus sequence typing (DLST) methods based on the partial sequencing of two highly variable loci to typing P. aeruginosa isolates which allowed us to obtain an unambiguous and standardized definition of types [12]. DLST has remarkable discriminatory power, reproducibility and is able to recognize high-risk epidemic clones [12]. Although blaNDM-1 positive isolates are rare, knowledge of its occurrence is considered as a serious menace, however, this study is the first report of DLST typing of blaNDM-1 positive P. aeruginosa isolates obtained from different part of Iran.

Methods

Study design, sampling, and bacterial isolates

A cross-sectional study was conducted at three major teaching Hospitals (Ahvaz, Tehran, and Isfahan) in Iran during three-year period. In total, 369 non-duplicate P. aeruginosa isolates were collected from different clinical sources such as trachea (84/369), wound (51/369), urine (79/369), punch biopsy (62/369), blood (34/369), sputum (35/369) and other (24/369). These samples were obtained from patient hospitalized in intensive care (ICU) and neonatal ICU (174/369), internal (149/369), emergency (11/369), other (15/369) and 20 samples from outpatients referred to laboratory center [13].

A total of 29 non-duplicate blaNDM-1 positive P. aeruginosa were collected from different clinical samples. The identification of P. aeruginosa was done by the conventional microbiology tests and confirmed by PCR with specific primers for gyrB gene [14].

PCR amplification of resistance genes

PCR amplification was performed for detection of blaNDM, blaIMP, blaVIM, blaKPC, blaGES, blaSPM and blaOXA-10 using a set of specific primers on a thermal cycler (Eppendorf AG, Germany) as described previously [15–17]. Sequencing of the amplicons was performed by the Bioneer Company (Bioneer, Daejeon, South Korea) and the nucleotide sequences were analyzed using GenBank nucleotide database at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Antibiotic susceptibility of the blaNDM-1 positive isolates was determined by the Kirby–Bauer method as recommended by the CLSI. The 11 standard antibiotic disks used include: imipenem (10 µg), meropenem (10 µg), ertapenem (10 µg), ceftazidime (30 µg), cefotaxime (30 µg), cefepime (30 µg), gentamicin (10 µg), piperacillin/tazobactam (100/10 µg), amikacin (30 µg), ciprofloxacin (5 µg) and aztreonam (30 µg) (Mast Group Ltd, UK). The ESBL phenotype was identified using combined disk method by disks of ceftazidime (30 mg) with (10 mg) and without clavulanic acid (Mast Group Ltd, UK), applied to all blaNDM−1 positive isolates (15). Moreover, the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of imipenem (10 µg/ml) [≤ 2 mg/L (susceptible), 4 mg/L (intermediate), and ≥ 8 mg/L (resistant)] (Liofilchem, Roseto degli Abruzzi, Italy) were applied by gradient test strips to blaNDM−1 positive P. aeruginosa isolates [18].

Carbapenemase screening

The double-disk potentiation tests (DDPT) and double disk synergy test (DDST) was performed phenotypically for all blaNDM−1 positive described by Yong et al. [19].

Double-locus sequence typing method

DLST typing was carried out using amplification of ms172 and ms217 loci using specific primers as previously described (Basset and Blanc, 2014) and according to DLST website (http://www.dlst.org/). PCR products were purified and were sequenced by Bioneer Corporation (Bioneer, Daejeon, South Korea).

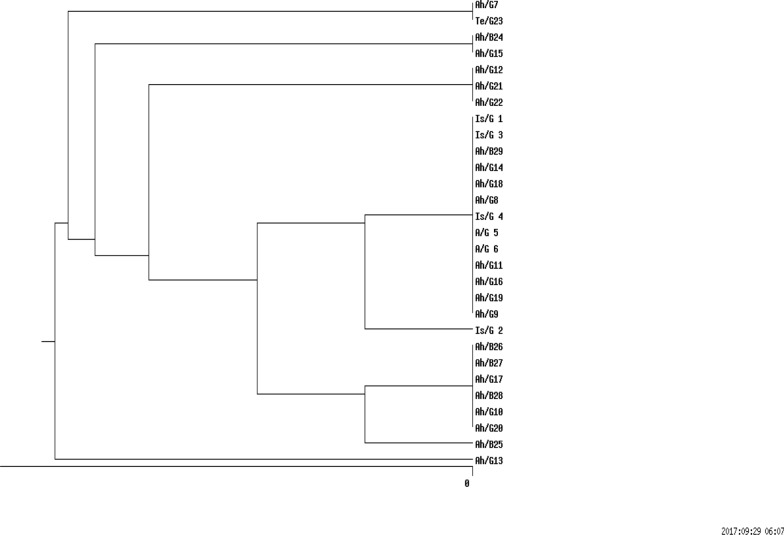

In the cases of any results of allele assignment, the allele was considered as a null allele. The allele profiles were compared and clustered by the UPGMA and Dice methods (Fig. 1), using an online data analysis service (nslico.ehu.es).

Fig. 1.

Dendrogram of DLST result analysis of 29 blaNDM-1 P. aeruginosa clinical strains isolated from hospitals in three different cities (Tehran, Ahvaz, Isfahan) of Iran. Results were clustered by UPGMA and compared by Dice Methods; Is; Isfahan, Ah; Ahvaz, Te; Tehran, G; General hospital, B; Burn hospital

Results

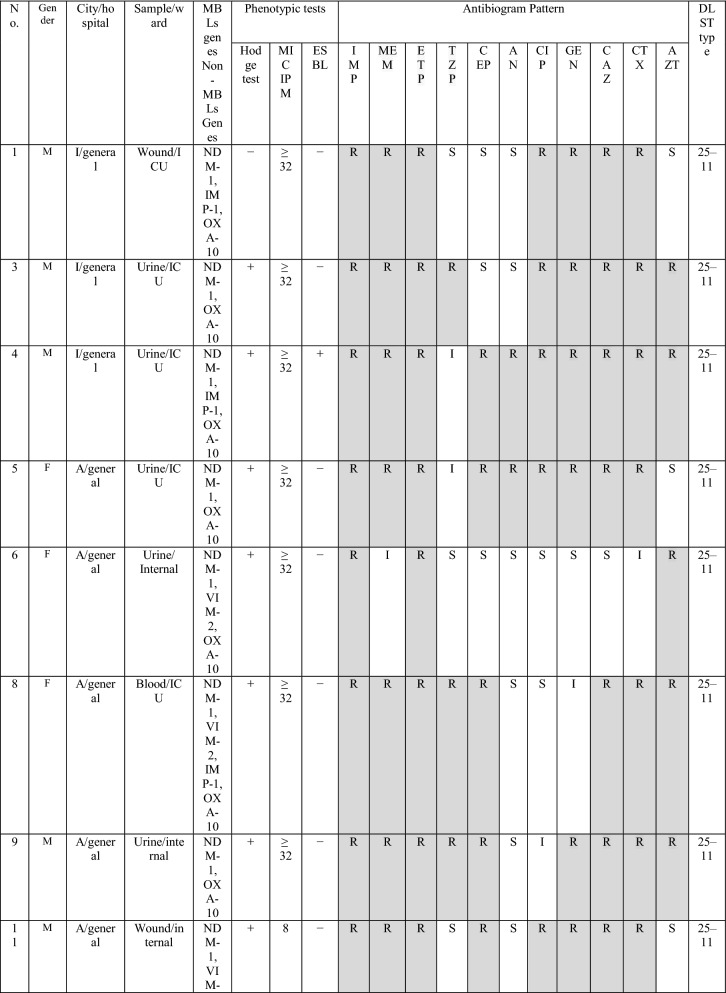

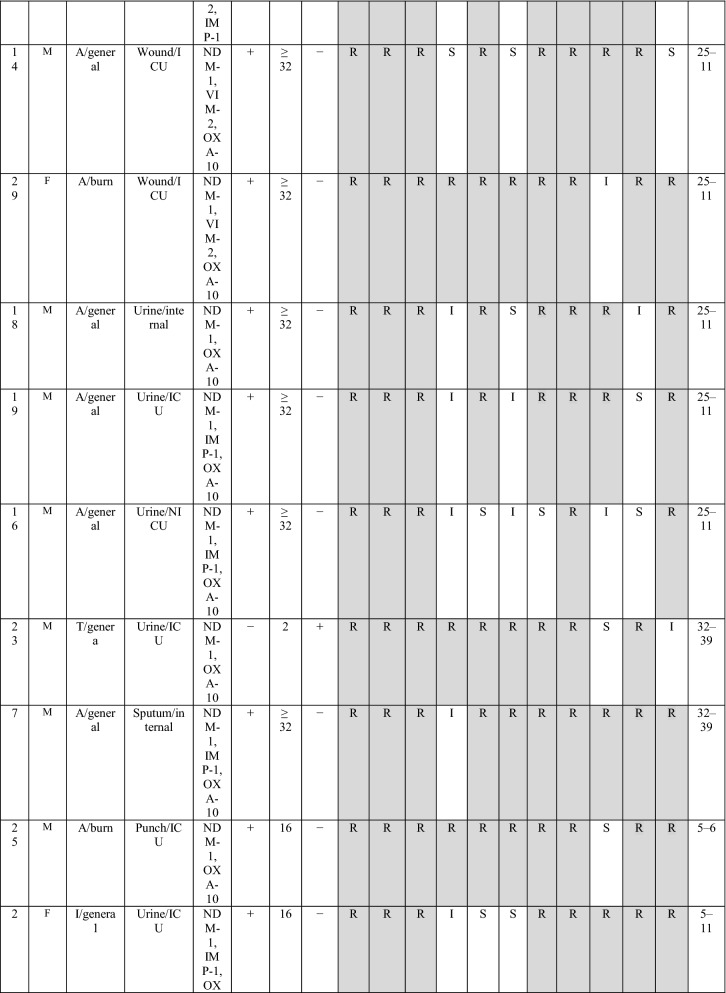

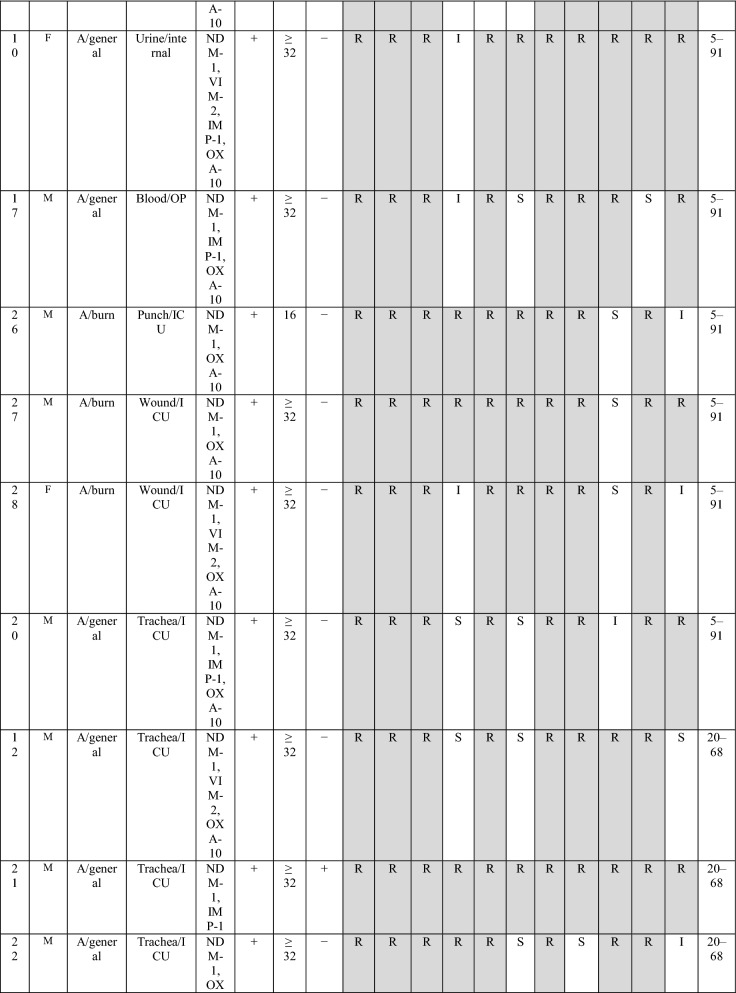

During the three years of study, twenty-nine of blaNDM-1 positive isolates were collected, of them, 6 (20.7%) and 23 (79.3%) isolates were from burn patients and non-burn patients, respectively. The male to the female proportion in blaNDM-1 isolates was 3.22 (n= 20:9). The most blaNDM-1 positive strains were isolated from wound/punch (n = 11; 37.9%) followed by urine (n = 11; 37.9%) samples, whereas, the majority of the blaNDM-1 isolates were obtained from ICU ward (n = 21: 72.4%), followed by internal ward (n = 6; 20.7%) and burn ward (n = 6; 20.7%) (Table 1). Antibiotic susceptibility pattern showed that all isolates were resistance to imipenem and ertapenem, moreover, the resistance rate of meropenem was 96.5%. In contrast, the highest sensitivity was against to piperacillin/tazobactam and amikacin (41.4%). All blaNDM-1 positive isolates were defined as MDR. The full results of antibiotic resistance pattern of blaNDM-1 positive P. aeruginosa isolates showed in Table 2.

Table 1.

The detailed results of P. aeruginosa with and without blaNDM-1

| Variable |

P. aeruginosa (without blaNDM-1) N=340 (%) |

P. aeruginosa (with blaNDM-1) N=29 (%) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 199 (58.5) | 20 (69) | 0.2 |

| Female | 141 (41.5) | 9 (31) | |

| Type of sample | |||

| Trachea | 80 (23.5) | 4 (13.8) | 0.2 |

| Urine | 68 (20) | 11 (37.9) | 197 |

| Punch | 60 (17.6) | 2 (6.9) | 0.1 |

| Wound | 42 (12.3) | 9 (31) | 0.005 |

| Sputum | 34 (10) | 1 (3.5) | 0.2 |

| Blood | 32 (9.4) | 2 (6.9) | 0.6 |

| Other | 24 (70.5) | – | – |

| Type of patients | |||

| Burn | 45 (13.2295) | 6 (20.7) | |

| ICU | 153 (45) | 21 (72.4) | 0.09 |

| Internal | 143 (42.1) | 6 (20.7) | 0.02 |

| Emergency | 11 (3.2) | – | – |

| Outpatients | 18 (5.3) | 2 (6.9) | 0.7 |

| Other | 15 (4.4) | – | – |

ICU Intensive care unit

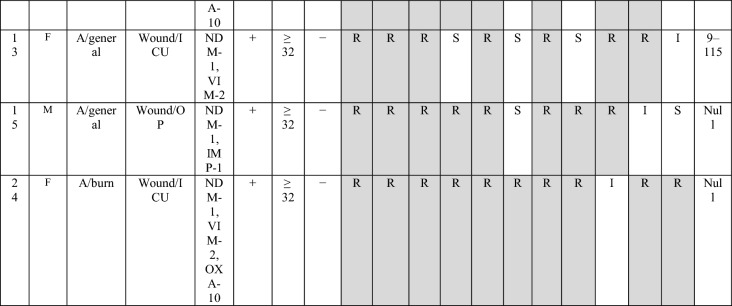

Table 2.

The detailed results of blaNDM−1 isolates

Imipenem (IPM), meropenem (MEM), ertapenem (ETP), piperacillin-tazobactam (TZP), cefepime (CFP), amikacin (AN), ciprofloxacin (CIP), gentamicin (GEN), ceftazidime (CAZ), cefexime (CTX), azteronam (AZT).َ A, Ahvaz; I, Isfahan; T, Tehran; OP, Outpatient; ICU

The MICs of imipenem against blaNDM−1 positive P. aeruginosa isolates are presented in Table 1. Overall, the results of MICs of imipenem showed 82.7% (24/29) isolates were high-level imipenem-resistant isolates (MIC ≥32). DDST and DDPT revealed that 15/29 (51.8%) and 26 (89.7%) of blaNDM-1 positive isolates were MBL producing isolates, respectively. In addition, the results of MHT showed that 27/29 (89.6%) of blaNDM−1 positive P. aeruginosa isolates were carbapenemase-producing isolates.

The distribution of carbapenemase genes and other antibiotic resistance genes among blaNDM-1 positive P. aeruginosa isolates are presented in Table 2. However, PCR analysis showed none of the blaNDM-1 positive P. aeruginosa isolates contained blaKPC and blaGES genes. The presence of blaVIM-2, blaIMP-1 and blaSPM genes were detected in 41.4%, 34.5% and 3.5% isolates, respectively. Among blaNDM-1 positive P. aeruginosa isolates, the blaOXA-10 beta-lactamase was the most frequently gene recognized in 86.2% (25/29).

The combination of blaVIM-2/ blaOXA-10 and blaIMP-1/blaOXA-10 beta-lactamase was found in 8 (27.6%) and 10 (34.5%) isolates, respectively. Moreover, among blaNDM-1 positive P. aeruginosa isolates the co-harboring of three genes, blaOXA-10, blaIMP-1 and blaVIM-2 was found in two isolates and only one isolate contained blaSPM that in combination with blaVIM-2 and blaOXA-10.

In the current study, the DLST method was tested for all blaNDM-1 isolates recovered over a period of four years from various hospital wards. DLST results revealed partial diversity among 29 blaNDM-1 positive isolates. Totally, 8 different DLST profile (DL type) (four different common types and three single type) were detected (Table 2). The most common type including 13 isolates (45%) from different hospitals (in Ahvaz and Isfahan). A total of 29, 27 sequences were ms172 and ms217 whereas, 2 strains carried null alleles for these loci. The DLST profile 5–91 were detected in 3 (50%) burn isolates. The details of information about DL type of P. aeruginosa isolates are presented in Table 2.

Discussion

P. aeruginosa, one of the most common opportunistic pathogen associated with nosocomial infections, including pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and wound infections [1, 20]. Although carbapenems are often used as a therapeutic agent for treating infections caused by P. aeruginosa, the high emergence of carbapenem resistance significantly decreases their usefulness [21, 22]. The presence of blaNDM−1 producing isolates which may increase resistance to carbapenems is increasing among patients in healthcare systems [23]. In the current study, we described molecular characterization of blaNDM-1 producing of P.aeruginosa isolates with phenotypic and genotypic methods.

The overall data show that the frequency of blaNDM-1 producing P. aeruginosa isolates was 7.8% (29/369). In addition, there are variable reports of blaNDM-1 from different countries in Europe and Asian. The blaNDM-1 producing P. aeruginosa isolates has been also detected in Iran, recently. Shokri et al. from Isfahan (Center of Iran) in 2017 reported 6% of P. aeruginosa isolates were blaNDM-1 positive which is slightly lower than the result obtained in the present study [24]. In another study, Dogonchi et al. reported one isolate of P. aeruginosa harboring blaNDM-1 in the north of Iran [25]. Recently, Azimi et al. described a lower frequency rate for blaNDM-1 (7%) among carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa [26]. Moreover, the blaNDM−1 gene was also revealed by Riahi Rad et al. in Iran (21.4%) [27] and Takahashi et al. in Nepal (7%) [28].

With regard to the fact that our isolates were collected from hospitals of different cities in Iran and also regarding the results of previous studies, an increasing trend of blaNDM-1 producing P. aeruginosa strains can be observed in Iranian hospitals where it could be an endemic and serious concern in future. One of the important reason of possible increase of this phenomenon among Gram-negative isolates is inappropriate and excessive prescription and use of carbapenems in our hospitals, which leads to selective pressure.

According to our results, the most blaNDM-1 positive isolates (72.4%) were collected from the ICU ward that these findings are broadly consistent with the previous studies conducted in Iran [24, 25]. This finding suggests that the ICU ward is can be a risk factor and major source for the dissemination of resistant genes in the Iranian hospitals. Our results presented that blaNDM-1 positive isolates had highly resistant to all antibiotics commonly used in the clinic which is in agreement with to the results of other studies [24, 29, 30].

In spite of the fact that the blaNDM-1 gene demonstrating the sensitivity of bacteria to aztreonam, 62% of blaNDM-1 positive isolates were resistant to this agent that could be related to the presence of other beta-lactamase genes. Based on screening of other carbapenemase and metallo β-lactamase genes, blaOXA-10 was the most frequently detected beta-lactamase among blaNDM-1 positive strain and blaIMP-1 was second, which is in contrast to other reports where blaVIM was significantly associated with blaNDM-1 [31, 32].

One of the important findings in this study was the emergence of the co-harboring of blaNDM-1 positive P. aeruginosa isolates with more than one carbapenemase gene and metallo β-lactamase determinants, simultaneously. Accordingly, we report the first isolate of P. aeruginosa producing four carbapenemases co-existence blaNDM-1, blaVIM--2, blaIMP-1 and blaOXA-10 from Iran. One of them that was obtained from urine sample was resistant to all antibiotics used except to TZP that were intermediate. Furthermore, we demonstrated the co-harboring of blaNDM-1 with metallo-β-lactamases genes such as blaOXA-10, blaIMP-1 and blaVIM-2 in P. aeruginosa. The coexistence of carbapenemases encoding genes with blaNDM-1 positive P. aeruginosa isolates has been reported in several Asian and European countries including in India (blaNDM-1 + blaIMP+ blaVIM+ blaSPM), Denmark (blaNDM-1 + bla VIM-5+ blaVIM-6) [33], Bangladesh (blaNDM-1, blaVIM-1, blaVIM-2, bla IMP-1) [34] and Turkey (blaVIM-1+ blaVIM-2+ blaGES-5 [35].

The previous studies revealed that the acquisition of MBL determinants such as blaNDM-1, bla VIM, bla IMP and blaSPM led to the emergence of MDR or XDR P. aeruginosa [36, 37].

To the extent of our knowledge, this study is the first to report of Molecular typing of blaNDM-1 positive isolates in P. aeruginosa by DLST method.

Among various genotyping technique, DLST as a reliable genotyping method, provide a new, rapid, typability, stability and low-cost of epidemiological surveillance of P. aeruginosa isolates [11, 38]. Analysis of DLST types revealed that the majority (19/29) of the isolates belonged to DLST type 25-11 and 5-91.

In addition, 8 blaNDM-1 positive isolates were clustered into two DLST types and 3 singletons. Accordingly, blaNDM-1 positive isolates were relatively heterogeneous, however, the route of transmission is not clear. These results highlight the importance of investigating carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa isolates in health care settings in our region.

Conclusions

The occurrence of blaNDM-1 isolates in P. aeruginosa is a large challenge in the treatment and worrying for global health. DLST type 25-11 is a significant cluster because a large number of blaNDM-1 isolates showed this genotype and also DLST type 5-91 known as an alarming type in burn patients. This work suggests that the DLST as an appreciated method in typing of blaNDM−1 strains; this technique reducing considerably the time and the cost of the molecular analysis and providing a reliable phylogenetic study. This information can help to generate the proper strategies for accurate and specific use of this antibacterial which can help to control of blaNDM-1 isolates.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to guidance and advice from “Clinical Research Development Unit of Baqiyatallah Hospital”.

Abbreviations

- ESBL

Extended-spectrum b-lactamases

- CLSI

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

- CCs

Clonal complex

- DLV

Double-locus variants

- DDST

Double-disk synergy test

- DDPT

Double-disk potentiation test

- KTP

Kidney transplant patients

- ST

Sequence types

- SLV

Single-locus variants

- SD

Standard deviation

- UPEC

Uropathogenic Escherichia coli

- UTI

Urinary tract infections

- MLST

Multilocus sequence typing

- VFs

Virulence factors

Authors’ contributions

AA designed the study and reviewed the manuscript, and edited the final version. MSH contributed to design the study, collected the data, and drafted the manuscript. AA analyzed the data, reviewed the manuscript, and edited the final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript

Funding

Self- funding.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was also confirmed and permitted by the Ethics Committee of Clinical Research Development Unit of Baqiyatallah Hospital” IR.BMSU.REC.1398.241”.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Floret N, Bertrand X, Thouverez M, et al. Nosocomial infections caused by Pseudomonasaeruginosa: exogenous or endogenous origin of this bacterium? Pathol Biol (Paris) 2009;57:9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:268–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gniadek TJ, Carroll KC, Simner PJ. Carbapenem-resistant non-glucose-fermenting gram-negative bacilli: the missing piece to the puzzle. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:1700–10. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03264-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakamura I, Yamaguchi T, Tsukimori A, et al. New options of antibiotic combination therapy for multidrug-resistant Pseudomonasaeruginosa. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34:83–7. doi: 10.1007/s10096-014-2192-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeannot K, Poirel L, Robert-Nicoud M, et al. IMP-29, a novel IMP-type metallo-β-lactamase in Pseudomonasaeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:2187–90. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05838-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jamal WY, Albert MJ, Rotimi VO. High prevalence of New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-1 (NDM-1) producers among carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Kuwait. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0152638. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kashyap A, Gupta R, Sharma R, et al. New Delhi metallo beta lactamase: menace and its challenges. J Mol Genet Med. 2017;11:1747–0862. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Queenan AM, Bush K. Carbapenemases: the versatile beta-lactamases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:440–58. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00001-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jovčić B, Lepšanović Z, Begović J, et al. Two copies of blaNDM-1 gene are present in NDM-1 producing Pseudomonasaeruginosa isolates from Serbia. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2014;105:613–8. doi: 10.1007/s10482-013-0094-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muir A, Weinbren MJ. New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase: a cautionary tale. J Hosp Infect. 2010;75:239–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basset P, Blanc DS. Fast and simple epidemiological typing of Pseudomonasaeruginosa using the double-locus sequence typing (DLST) method. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33:927–32. doi: 10.1007/s10096-013-2028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cholley P, Stojanov M, Hocquet D, et al. Comparison of double-locus sequence typing (DLST) and multilocus sequence typing (MLST) for the investigation of Pseudomonasaeruginosa populations. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;82:274–7. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2015.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farajzadeh Sheikh A, Shahin M, Shokoohizadeh L, et al. Molecular epidemiology of colistin-resistant Pseudomonasaeruginosa producing NDM-1 from hospitalized patients in Iran. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2019;22:38–42. doi: 10.22038/ijbms.2018.29264.7096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lavenir R, Jocktane D, Laurent F, et al. Improved reliability of Pseudomonasaeruginosa PCR detection by the use of the species-specific ecfX gene target. J Microbiol Methods. 2007;70:20–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nordmann P, Naas T, Poirel L. Global spread of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1791–8. doi: 10.3201/eid1710.110655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shacheraghi F, Shakibaie MR, Noveiri H. Molecular identification of ESBL Genes blaGES-blaVEB-blaCTX-M blaOXA-blaOXA-4, blaOXA-10 andblaPER-in Pseudomonasaeruginosa strains isolated from burn patients by PCR, RFLP and sequencing techniques. Int J Biol life Sci. 2010;37:1189–1193. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golshani Z, Sharifzadeh A. Prevalence of blaOxa10 type beta-lactamase gene in carbapenemase producing Pseudomonasaeruginosa strains isolated from patients in Isfahan. 2013;6.

- 18.Wayne P. CLSI. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twenty-second. Informational supplement CLSI document M100–S33. Wayne: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yong D, Lee K, Yum JH, et al. Imipenem-EDTA disk method for differentiation of metallo-beta-lactamase-producing clinical isolates of Pseudomonas spp. and Acinetobacter spp. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:3798–801. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.10.3798-3801.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alavi Foumani A, Yaghubi Kalurazi T, Mohammadzadeh Rostami F, et al. Epidemiology of Pseudomonasaeruginosa in cystic fibrosis patients in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infez Med. 2020;28:314–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ellappan K, Narasimha H, Kumar S. Coexistence of multidrug resistance mechanisms and virulence genes in carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonasaeruginosa strains from a tertiary care hospital in South India. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2018;12:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2017.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faghri J, Nouri S, Jalalifar S, et al. Investigation of antimicrobial susceptibility, class I and II integrons among Pseudomonasaeruginosa isolates from hospitalized patients in Isfahan, Iran. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:806. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3901-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khajuria A, Praharaj AK, Kumar M, et al. Emergence of NDM-1 in the clinical isolates of Pseudomonasaeruginosa in India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:1328–31. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/5509.3137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shokri D, Rabbani Khorasgani M, Fatemi SM, et al. Resistotyping, phenotyping and genotyping of New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (NDM) among Gram-negative bacilli from Iranian patients. J Med Microbiol. 2017;66:402–11. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dogonchi AA, Ghaemi EA, Ardebili A, et al. Metallo-β-lactamase-mediated resistance among clinical carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonasaeruginosa isolates in northern Iran: a potential threat to clinical therapeutics. Tzu-Chi Med J. 2018;30:90. doi: 10.4103/tcmj.tcmj_101_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rad ZR, Rad ZR, Goudarzi H, et al. Detection of New Delhi Metallo-β-lactamase-1 among Pseudomonasaeruginosa isolated from adult and pediatric patients in Iranian hospitals. Gene Rep. 2021;23:101152. doi: 10.1016/j.genrep.2021.101152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Azimi L, Fallah F, Karimi A, et al. Survey of various carbapenem-resistant mechanisms of Acinetobacterbaumannii and Pseudomonasaeruginosa isolated from clinical samples in Iran. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2020;23:1396–400. doi: 10.22038/IJBMS.2020.44853.10463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takahashi T, Tada T, Shrestha S, et al. Molecular characterisation of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonasaeruginosa clinical isolates in Nepal. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2021;26:279–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2021.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohanam L, Menon T. Coexistence of metallo-beta-lactamase-encoding genes in Pseudomonasaeruginosa. Indian J Med Res. 2017;146:46-s52. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_29_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaaban M, Al-Qahtani A, Al-Ahdal M, et al. Molecular characterization of resistance mechanisms in Pseudomonasaeruginosa isolates resistant to carbapenems. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2017;11:935–43. doi: 10.3855/jidc.9501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paul D, Dhar D, Maurya AP, et al. Occurrence of co-existing bla VIM-2 and bla NDM-1 in clinical isolates of Pseudomonasaeruginosa from India. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2016;15:31. doi: 10.1186/s12941-016-0146-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rahman M, Prasad KN, Gupta S, et al. Prevalence and molecular characterization of new Delhi metallo-beta-lactamases in multidrug-resistant Pseudomonasaeruginosa and Acinetobacterbaumannii from India. Microbial Drug Resist. 2018;24:792–8. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2017.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang M, Borris L, Aarestrup FM, et al. Identification of a Pseudomonasaeruginosa co-producing NDM-1, VIM-5 and VIM-6 metallo-β-lactamases in Denmark using whole-genome sequencing. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2015;45:324–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farzana R, Shamsuzzaman S, Mamun KZ. Isolation and molecular characterization of New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase-1 producing superbug in Bangladesh. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2013;7:161–8. doi: 10.3855/jidc.2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malkocoglu G, Aktas E, et al. VIM-1, VIM-2, and GES-5 carbapenemases among Pseudomonasaeruginosa isolates at a tertiary hospital in Istanbul. Turkey Microb Drug Resist. 2017;23:328–34. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2016.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paul D, Dhar Chanda D, Maurya AP, et al. Co-carriage of blaKPC-2 and blaNDM-1 in clinical isolates of Pseudomonasaeruginosa associated with hospital infections from India. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0145823. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Flateau C, Janvier F, Delacour H, et al. Recurrent pyelonephritis due to NDM-1 metallo-beta-lactamase producing Pseudomonasaeruginosa in a patient returning from Serbia, France, 2012. Eurosurveillance. 2012;17:20311. doi: 10.2807/ese.17.45.20311-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pappa O, Beloukas A, Vantarakis A, et al. Molecular characterization and phylogenetic analysis of Pseudomonasaeruginosa isolates recovered from Greek aquatic habitats implementing the double-locus sequence typing scheme. Microb Ecol. 2017;74:78–88. doi: 10.1007/s00248-016-0920-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.