Abstract

Background:

Pramipexole (P) or levodopa (L) treatment has been suggested as a therapeutic method for Parkinson disease (PD) in many clinical studies. Nonetheless, the combined effects of 2 drugs for PD patients are not completely understood.

The aim of this research was to evaluate the clinical efficacy and safety of P plus L (P+L) combination therapy in the treatment of PD compared to that of L monotherapy, in order to confer a reference for clinical practice.

Methods:

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of P+L for PD published up to April, 2020 were retrieved. Standardized mean difference (SMD), odds ratio (OR), and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated and heterogeneity was measured with the I2 test. Sensitivity analysis was also carried out. The outcomes of interest were as follows: the efficacy, unified Parkinson disease rating scale (UPDRS) scores, Hamilton depression rating scale score or adverse events.

Results:

Twenty-four RCTs with 2171 participants were included. Clinical efficacy of P+L combination therapy was significantly better than L monotherapy (9 trials; OR 4.29, 95% CI 2.78 to 6.64, P < .00001). Compared with L monotherapy, the pooled effects of P+L combination therapy on UPDRS score were (22 trials; SMD −1.31, 95% CI −1.57 to −1.04, P < .00001) for motor UPDRS score, (16 trials; SMD −1.26, 95% CI −1.49 to −1.03, P < .00001) for activities of daily living UPDRS score, (12 trials; SMD −1.02, 95% CI −1.27 to −0.77, P < .00001) for mental UPDRS score, (10 trials; SMD −1.54, 95% CI −1.93 to −1.15, P < .00001) for complication UPDRS score. The Hamilton depression rating scale score showed significant decrease in the P+L combination therapy compared to L monotherapy (12 trials; SMD −1.56, 95% CI −1.90 to −1.22, P < .00001). In contrast to L monotherapy, P+L combination therapy reduced the number of any adverse events obviously in PD patients (16 trials; OR 0.36, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.50, P < .00001).

Conclusions:

P+L combination therapy is superior to L monotherapy for improvement of clinical symptoms in PD patients. Moreover, the safety profile of P+L combination therapy is better than that of L monotherapy. Further well-designed, multicenter RCTs needed to identify these findings.

Keywords: levodopa, meta-analysis, Parkinson disease, pramipexole, safety, UPDRS

1. Introduction

Parkinson disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disease. With the acceleration of global population aging, the incidence of PD is increasing year by year. The clinical symptoms of PD mainly include bradykinesia, resting tremor, and myotonia. Psychological disorders may also occur in patients with advanced PD.[1] At present, the etiology of PD is not yet clear, which makes the treatment difficult. The improvement of PD patients’ condition is mainly achieved by increasing dopamine level in the brain. Levodopa (L) is the mainstay of treatment for PD patients, which can supplement dopamine in the brain and improve the extrapyramidal function.[2] However, long-term use of L will cause adverse reactions such as “on-off” phenomenon, dyskinesia and wearing off phenomenon,[3,4] furthermore, some patients’ condition will be irreversible throughout their lives. Pramipexole (P) is a dopamine receptor agonist designed to improve the clinical signs and symptoms of adult idiopathic PD.[5,6] In other words, when the efficacy of L is gradually weakened, or “on-off” fluctuation occur during the course of disease, P can be used alone or in combination with L for PD patients.[7,8] The exact mechanisms of P in the treatment of PD remain unclear. The current researches show that the combination of P and L can stimulate the dopamine receptor of PD patients, prolong the half-life of L in vivo, significantly reduce the dose of L, and promote the alleviation of motor and non-motor symptoms.[9,10]

Numerous clinical randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have proved that the P plus L (P+L) combination therapy has more remarkable effects and fewer adverse events than L monotherapy in the treatment of PD.[8,11] Nevertheless, the sample sizes of these trials are too small, and they are all single-center studies. What's more, there is still a phenomenon that the results are not completely consistent, some studies have demonstrated that the addition of P to L in the treatment of PD patients can not significantly reduce the incidence of adverse events.[11,12] These factors lead to insufficient evidence that combination therapy of 2 drugs is clinically effective in the treatment of PD. At present, there is no meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of P and L in the treatment of PD patients. This study aims to systematically evaluate the clinical efficacy of adjunctive P in L-treated patients with PD, in order to provide a reference for the choice of drugs for PD patients.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy

This meta-analysis was performed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.[13] The electronic databases of PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, Embase, Cochrane Library, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure Database and Wanfang Database were searched without language restrictions, from the earliest available date to April 1, 2020. The key terms used in this search were (Parkinson's disease or Parkinson disease or Parkinson or PD) and (pramipexole or sifrol or mirapex or mirapexin or praxol) and (levodopa or L-dopa or larodopa).

2.2. Study selection criteria

Studies were included if they met all eligibility criteria, stated as: study types were RCTs. Patients were clinically diagnosed with any stage of idiopathic PD. Patients in experimental group were correspondingly treated with P and L, and patients in control group were treated with L. Data on changes in efficacy, unified Parkinson disease rating scale (UPDRS) scores, Hamilton depression rating scale (HAMD) score or adverse events could be extracted. The exclusion criteria included: cross-over trials and quasi-randomised trials. Trials with some deficiencies in data, or original data displayed as figures. Trials were excluded if participants had another neurodegenerative disorder besides PD, an unstable cardiac disorder, or clinically significant hepatic, lung, or renal disease. Animal or basic experiments, and unavailability of full text.

2.3. Data extraction

Data of the independent variables including patient baseline characteristics, study durations, initial or maintenance doses of drugs, pharmaceutical dosage forms, were summarised independently by the investigators. The primary outcomes of interest consisted of efficacy, motor UPDRS score, activities of daily living (ADL) UPDRS score, mental UPDRS score, complication UPDRS score, or HAMD score. Moreover, the secondary outcome was adverse events. Clinical efficacy was divided into 3 categories: markedly effective (percentage of decrease in motor UPDRS score or modified Webster scale score from baseline to end-of-treatment visit was ≥50%), effective (percentage of decrease in motor UPDRS score or modified Webster scale score was 50% to 10%), and ineffective (percentage of decrease in motor UPDRS score or modified Webster scale score from baseline to end-of-treatment visit was <10%).

2.4. Quality assessment

The established Jadad scale was used to measure the methodological quality of included studies by the authors.[14] Four to seven points indicated high-quality trials, and 0 to 3 points indicated poor or low-quality trials. In case of disagreements regarding the risk of quality assessment, discussion was conducted until a consensus was reached.

2.5. Ethical approval

All the data in present meta-analysis were extracted from the previous published studies, no ethical approval or patient consent was required.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The weighted standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were estimated for continuous data (changes in various UPDRS scores or HAMD score), and dichotomous data (efficacy or adverse events) were expressed as odds ratio (OR) and 95% CIs. Heterogeneity test was performed by Q test and I2 statistics, when the significant heterogeneity existed (I2 > 50% or P ≤ .10), the random-effect (RE) model was used for analysis, otherwise, the fixed-effect (FE) model was used.[15] The possibility of publication bias was tested by funnel plot and Egger test. The influence of a single study on the overall pooled estimate was investigated by excluding 1 trial in each turn. A P value less than.05 was judged as statistically significant. All statistical analysis were performed using RevMan 5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK) and Stata 12.0 softwares (StataCorp, TX).

3. Results

3.1. Description of the studies

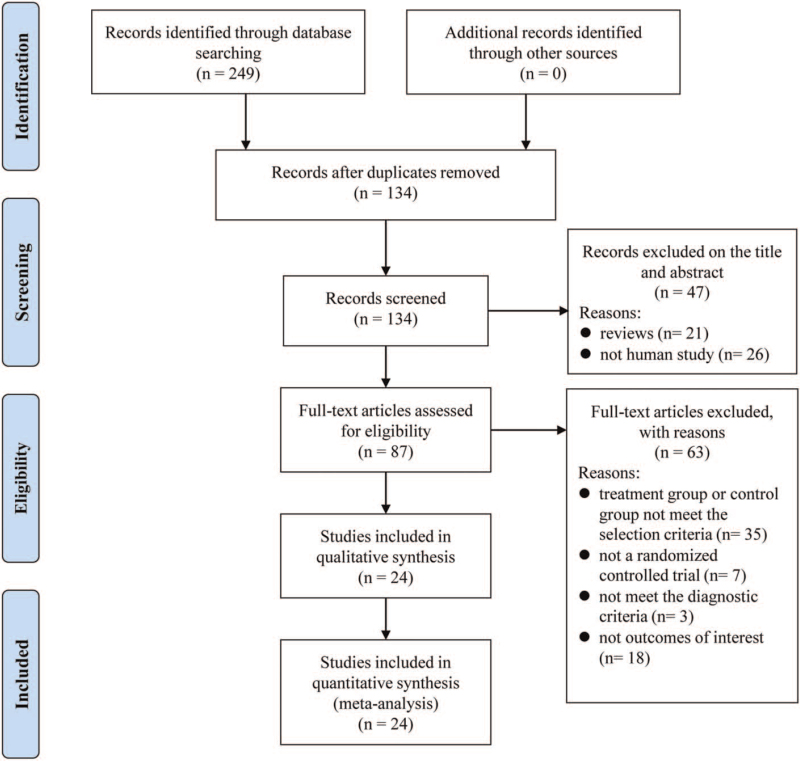

The process of the study selection was presented in Figure 1. Two hundred forty-nine potentially relevant articles were retrieved from the initial searches, but only 24 studies[8,11,12,16–36] satisfying the inclusion and exclusion criteria were selected for this analysis. The key characteristics of the 24 RCTs and Jadad scores were shown in Table 1. One thousand ninety-two PD patients were included in the P+L combination therapy group and 1079 PD patients were included in the L monotherapy group. The treatment durations varied from 2 months to 18 weeks. Only 2 studies[21,22] didnot report the PD duration. The initial dose of P was 0.375 mg/d in 18 studies, and the maintenance dose of P ranged from.25 to 4.5 mg/d in all RCTs. The dosage forms of P used in the 2 trials[18,28] were sustained-release formulations, and the others were immediate-release preparations. The number of any adverse events was not available in 8 trials.[8,16,18,20–23,31] Twelve studies[8,17,24,25,28–35] with 4 or larger points were of high quality and the remaining studies with 3 or lower points were all of low quality.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study selection in the meta-analysis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis.

3.2. Efficacy

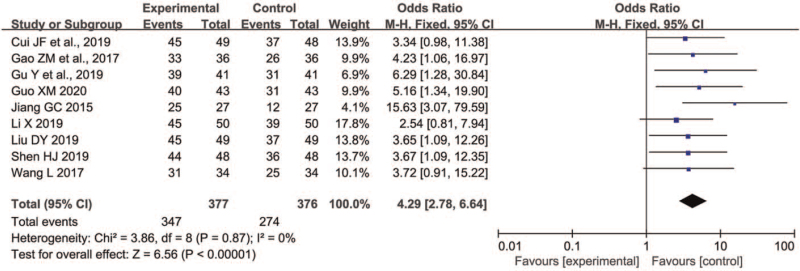

Nine trials[11,17–19,21–23,28,31] involving a total of 753 participants measured the efficacy (377 receiving P+L combination therapy and 376 receiving L monotherapy). As shown in Figure 2, the FE model was used because insignificant heterogeneity between trials for 2 groups was observed (P = .87, I2 = 0%). In contrast to L monotherapy, P+L combination therapy for PD markedly improved the efficacy (OR 4.29, 95% CI 2.78 to 6.64, P < .00001). On sensitivity analyses, we found the I2 value was 0% unchangeably and the Z value for overall effect ranged from 5.76 to 6.56, which indicated the result was very robust.

Figure 2.

Comparison of P+L combination therapy and L monotherapy in the clinical efficacy for Parkinson disease. L = levodopa; P = pramipexole.

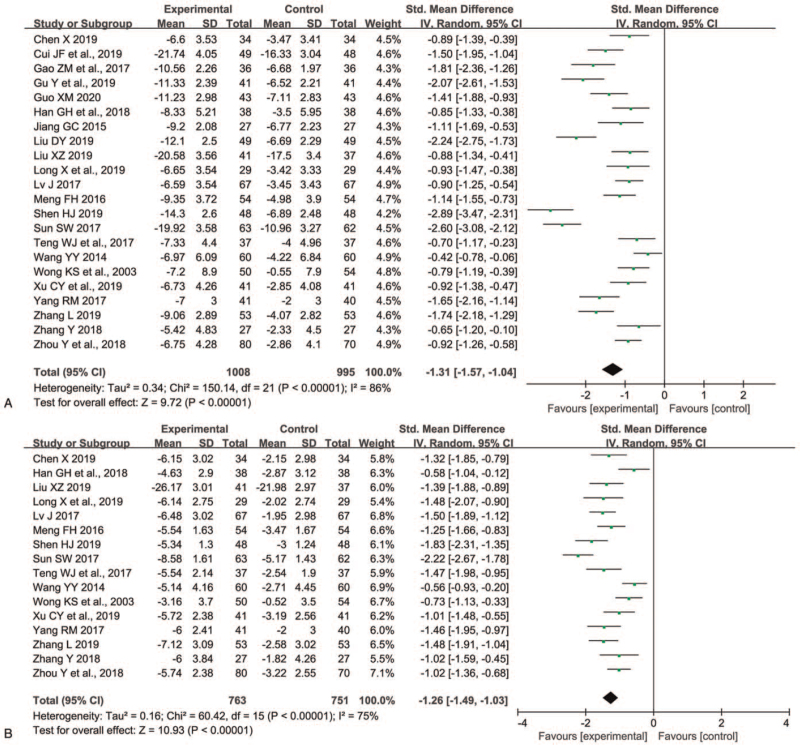

3.3. Motor UPDRS score

Twenty-two trials[8,11,12,16–21,23–30,32–36] involving 2003 patients measured the motor UPDRS score. As shown in Figure 3A, the RE model was used because remarkable heterogeneity between trials for 2 groups was discovered (P < .00001, I2 = 86%). Compared with L monotherapy, P+L combination therapy declined motor UPDRS score dramatically (SMD -1.31, 95% CI -1.57 to -1.04, P < .00001). On sensitivity analyses, we found the I2 value ranged from 83% to 87% and the Z value for overall effect ranged from 9.24 to 10.15, which implied the result was very stable.

Figure 3.

Comparison of P+L combination therapy and L monotherapy in the motor UPDRS score (A) and ADL UPDRS score (B) for Parkinson disease. ADL = activities of daily living; L = levodopa; P = pramipexole, UPDRS = unified Parkinson disease rating scale.

3.4. ADL UPDRS score

Sixteen trials[8,12,16,20,24–30,32–36] involving 1514 patients evaluated the ADL UPDRS score. As shown in Figure 3B, the RE model was used because significant heterogeneity between trials for 2 groups was observed (P < .00001, I2 = 75%). P+L combination therapy had lower ADL UPDRS score than L monotherapy in patients with PD (SMD -1.26, 95% CI -1.49 to -1.03, P < .00001). The sensitivity analyses displayed that the I2 value ranged from 65% to 77% and the Z value for overall effect ranged from 10.15 to 11.93, which suggested the result was robust.

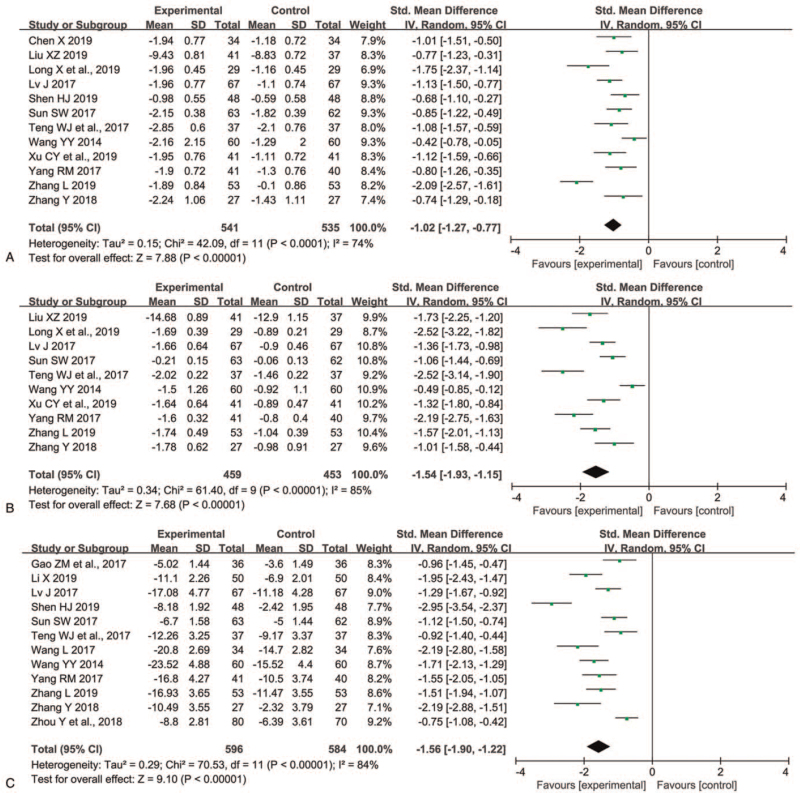

3.5. Mental UPDRS score

Twelve trials[16,24–26,28–30,32–36] involving 1076 participants assessed the mental UPDRS score. As shown in Figure 4A, heterogeneity was obvious for the analysis (P < .0001, I2 = 74%), the RE model was used. In contrast to L monotherapy, P+L combination therapy improved mental UPDRS significantly (SMD -1.02, 95% CI -1.27 to -0.77, P < .00001). On sensitivity analyses, after excluding the study reported by Zhang,[35] the I2 value ranged from 74% to 48% and the overall effect ranged from (Z = 7.88, P < .00001) to (Z = 9.49, P < .00001).

Figure 4.

Comparison of P+L combination therapy and L monotherapy in the mental UPDRS score (A), complication UPDRS score (B), and HAMD score (C) for Parkinson disease. HAMD = Hamilton depression rating scale; L = levodopa; P = pramipexole; UPDRS = unified Parkinson disease rating scale.

3.6. Complication UPDRS score

Ten trials[24–26,29,30,32–36] involving 912 patients evaluated the complication UPDRS score. The RE model was used because significant heterogeneity between trials for 2 groups was observed (P < .00001, I2 = 85%). The complication UPDRS score showed significant decrease in the P+L combination therapy group compared to L monotherapy group (SMD -1.54, 95% CI -1.93 to -1.15, P < .00001) (Figure 4B). The sensitivity analyses showed that the I2 value ranged from 77% to 87% and the Z value for overall effect ranged from 6.78 to 9.51, which implied the result was stable.

3.7. HAMD score

Twelve trials[12,17,22,26,28–32,34–36] involving 1180 patients measured the HAMD score. Heterogeneity was obvious for the analysis (P < .00001, I2 = 84%), the RE model was used. The P+L combination therapy group had lower HAMD score than that of L monotherapy group (SMD -1.56, 95% CI -1.90 to -1.22, P < .00001) (Figure 4C). On sensitivity analyses, we found the I2 value ranged from 77% to 86% and the Z value for overall effect ranged from 8.30 to 9.95, which suggested the result was robust.

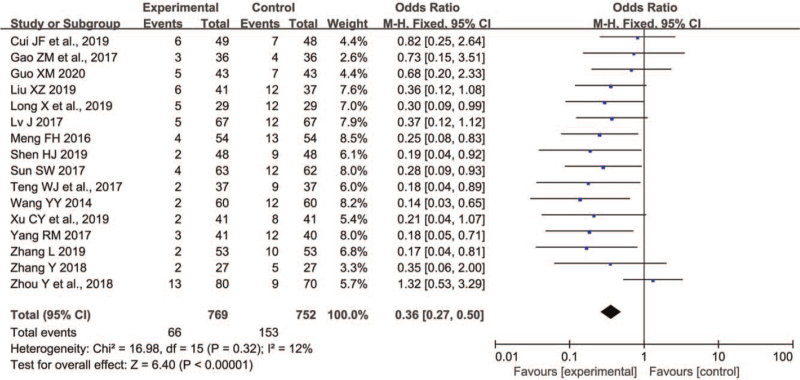

3.8. Safety

Sixteen trials[11,12,17,19,24–30,32–36] involving 1521 patients reported the number of adverse events, 769 participants received P+L combination therapy and 752 participants received L monotherapy. As shown in Figure 5, the FE model was used because insignificant heterogeneity between trials for 2 groups was discovered (P = .32, I2 = 12%). Compared with L monotherapy, P+L combination therapy for PD decreased the number of any adverse events significantly (OR 0.36, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.50, P < .00001). On sensitivity analyses, we found the I2 value ranged from 0% to 18% and the Z value for overall effect ranged from 5.91 to 6.88, which indicated the result was robust. The most commonly reported adverse events in the PD patients treated with P and L were nausea, dizziness, insomnia, constipation, somnolence, or anorexia. Because most studies did not report these side effects in detail, we were unable to analyze the rates of various adverse events, respectively.

Figure 5.

Comparison of P+L combination therapy and L monotherapy in the any adverse events for Parkinson disease. L = levodopa; P = pramipexole.

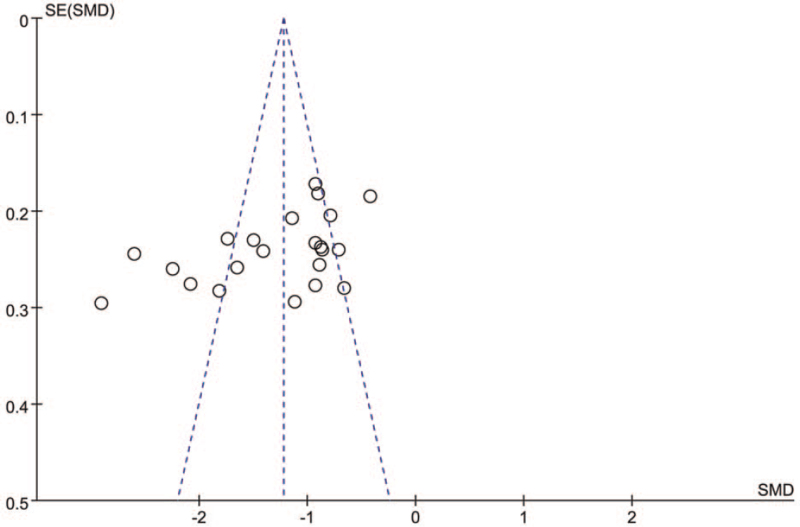

3.9. Publication bias

The Egger test for publication bias for all motor UPDRS score trials implied a possible publication bias with P > |t| = .014 (CI −15.488, −1.998). The funnel shape according to the motor UPDRS score was not symmetrical (Fig. 6), also indicating a potential publication bias.

Figure 6.

Funnel plot for estimation of potential publication bias.

4. Discussion

L, a precursor of dopamine, is an intermediate product in the process of catecholamine production from tyrosine. After entering the central nervous system through the blood-brain barrier, L can elevate the concentration of dopamine in brain to a certain extent under the action of decarboxylase, which can help relieve degenerative lesions of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons in the midbrain, thereby reducing the clinical symptoms of PD patients.[37] However, after L enters the blood circulation system, only a small part of it can enter the cerebral circulation through the blood-brain barrier, whereas about 95% of it cannot cross the blood-brain barrier and is broken down into catecholamine by the action of dopa-decarboxylase in peripheral tissues.[38] Catecholamine can stimulate vascular alpha receptors to promote vasoconstriction, accelerate heart rate, increase cardiac output, accelerate oxygen and energy consumption. Due to the long course of disease and long duration of L therapy in PD patients, the accumulation of catecholamine acidic metabolites in alimentary canal or peripheral organs is promoted,[39] and then the clinical adverse events in digestive system, central nervous system and cardiovascular system are presented, which reduces the safety of L in the treatment of PD. Moreover, with the prolongation of medication, the efficacy of L gradually decreases, and patients may also have adverse events such as wearing-off fluctuations, dyskinesia, and morning stiffness.[40] Therefore, exploring a safe and effective therapeutic method for PD and choosing anti-PD drugs combined with L preparation to improve the anti-PD efficacy and decrease the incidence of adverse events have always been a hot issue in the research area of neurologists.

With the development of drug research, dopamine receptor agonist drugs have been applied in clinical practice, reducing the application defects of L and effectively improving the clinical symptoms of PD patients. The results of this study proved that, compared with L alone, P+L combo therapy in the treatment of PD patients could significantly elevate the treatment efficiency and reduce motor UPDRS score, ADL UPDRS score, mental UPDRS score and complication UPDRS score. The motor function, daily activity ability, and mental symptoms of PD patients have been dramatically improved. P is a synthetic aminobenzothiazole derivative and belongs to a non-ergot dopaminergic agonist. P has strong affinity to dopaminergic D2/D3 receptors. P can selectively and specifically bind to dopamine D2 receptor to promote dopamine release. Studies have proved that P can stimulate D2 receptor to quickly alleviate the clinical symptoms and can also activate D3 receptor to effectively relieve depression in PD patients.[41,42] We also found that the HAMD score of the combined drugs group was dramatically lower than that of the single drug group. Experimental studies display that P can inhibit the generation of free radicals to protect dopaminergic neurons, and also suppress the production of quinone groups to reduce its damage to substantia nigra cells,[43] which reduce the emergence of adverse events. The results of this study suggested that the incidence of side effects of combination medication was remarkably lower than that of L alone. On the 1 hand, P treatment can effectively improve the adverse symptoms and the pathology changes in substantia nigra of PD patients,[44] on the other hand, it can reduce the clinical dosage of L and avoid adverse drug reactions caused by long-term and large-scale medication, so P+L combo therapy has better drug safety than L monotherapy.[9,45] In this study, the maintenance dose of L in combination group was 375 mg/d in 6 studies, which was obviously smaller than the 3000 to 6000 mg/d in L monotherapy group. In addition, the following problems should be paid attention to during the P treatment: starting from a small dose in the early stage, observing the patient's tolerance, and adjusting the drug dosage according to the tolerance.

The limitations of this systematic review are as follows: Most of the included RCTs donot account for allocation concealment, and some trials have certain shortcomings in randomization or double-blind, which lead to a high risk of bias and reduce the reliability of results of this study. The modified Jadad scale was used for methodological quality evaluation, only half of the RCTs were of high quality and the others were of low quality, which would also have a negative impact on the stability of the data. The included RCTs are all published literatures, most of them have positive results. It is possible that some research papers with negative results are not included, resulting in a certain degree of publication bias. The maintenance dose of P is in the range of 0.25 to 4.5 mg/d, due to the unclear dose grouping in some RCTs, the optimal dosage of P cannot be scientifically evaluated. The adverse reaction has not been reported or the report is not specific, so the incidence of each adverse event cannot be measured.

In addition, most of studies included in this meta-analysis have small number of patients, all of them were single-center trials. In the future, the sample size of clinical trials could be increased and multicenter, large-sample RCTs should be carried out. Furthermore, future clinical research should also extend the follow-up time to observe the long-term efficacy of P+L in PD patients, and track the disease development to understand the changes in the UPDRS scores of patients after long-term treatment, so as to obtain comprehensive clinical trial results.

In conclusion, we have systematically reviewed and synthesized published literature reporting on the efficacy of P as add-on therapy in L-treated patients with PD. It has been elucidated that the UPDRS and HAMD scores of patients in the experimental group receiving P and L were obviously less than those in the control group receiving L alone, and the incidence of adverse events was markedly lower than that in the control group. P+L combo therapy has a significant effect in the treatment of PD, which can dramatically improve the patients’ motor function and mental symptoms, and relieve the patients’ depression, furthermore, it is of high drug safety. However, the conclusions of this study need to be further confirmed by large-sample and high-quality RCTs.

Author contributions

Investigation: Yan Wang, De-Qi Jiang.

Methodology: De-Qi Jiang, Cheng-Shu Lu, Ming-Xing Li, Yan Wang, Li-Lin Jiang.

Writing – original draft: Yan Wang.

Writing – review & editing: De-Qi Jiang.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ADL = activities of daily living; CI = confidence interval; FE = fixed-effect; HAMD = Hamilton depression rating scale; L = levodopa; OR = odds ratio; P = pramipexole; PD = Parkinson disease; RCTs = randomized controlled trials; RE = random-effect; SMD = standardized mean difference; UPDRS = unified Parkinson disease rating scale.

How to cite this article: Wang Y, Jiang DQ, Lu CS, Li MX, Jiang LL. Efficacy and safety of combination therapy with pramipexole and levodopa vs levodopa monotherapy in patients with Parkinson disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2021;100:44(e27511).

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- [1].Stutts LA, Speight KL, Yoo S, et al. Positive psychological predictors of psychological health in individuals with Parkinson's disease. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2020;27:182–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Jiang DQ, Wang HK, Wang Y, et al. Rasagiline combined with levodopa therapy versus levodopa monotherapy for patients with Parkinson's disease: a systematic review. Neurol Sci 2020;41:101–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Gupta HV, Lyons KE, Wachter N, et al. Long term response to levodopa in Parkinson's disease. J Parkinsons Dis 2019;9:525–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Delamarre A, Tison F, Li Q, et al. Assessment of plasma creatine kinase as biomarker for levodopa-induced dyskinesia in Parkinson's disease. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2019;126:789–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Jiang DQ, Jiang LL, Wang Y, et al. The role of pramipexole in the treatment of patients with depression and Parkinson's disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Asian J Psychiatr 2021;61:102691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Zhou H, Li S, Yu H, et al. Efficacy and safety of pramipexole sustained release versus immediate release formulation for nocturnal symptoms in Chinese patients with advanced Parkinson's disease: a pilot study. Parkinsons Dis 2021;2021:8834950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jiang DQ, Zang QM, Jiang LL, et al. Comparison of pramipexole and levodopa/benserazide combination therapy versus levodopa/benserazide monotherapy in the treatment of Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2021;394:1893–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wong KS, Lu CS, Shan DE, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of pramipexole in untreated and levodopa-treated patients with Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Sci 2003;216:81–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Utsumi H, Okuma Y, Kano O, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy of pramipexole for treating levodopa-induced dyskinesia in patients with Parkinson's disease. Intern Med 2013;52:325–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Huang J, Hong W, Yang Z, et al. Efficacy of pramipexole combined with levodopa for Parkinson's disease treatment and their effects on QOL and serum TNF-α levels. J Int Med Res 2020;48:300060520922449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- [11].Cui JF, Chang LX, Jin HB. Effect of pramipexole combined with levodopa on Parkinson's disease and stress response. Sichuan J Physiol Sci 2019;41:210–2. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zhou Y, Chen L, Dai J, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of levodopa combined with pramipexole in treatment of Parkinson's disease. Drug Eval Res 2018;41:2262–5. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Open Med 2009;3:e123–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996;17:01–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Chen X. Clinical observation of pramipexole combined with levodopa in the treatment of patients with Parkinson's disease. Tibetan Med 2019;40:78–80. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Gao ZM, He JQ, Jiang HB, et al. Therapeutic effect of levodopa combined with pramipexole on subjects with Parkinson's disease. Chin Prev Med 2017;18:370–3. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gu Y, Yu JF, Wu YH. Effectiveness analysis of levodopa combined with pramipexole in treatment of Parkinson's disease. Smart Healthcare 2019;5:116–7. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Guo XM. Clinical efficacy of levodopa combined with pramipexole in the treatment of Parkinson's disease and its effect on motor function in patients. Chronic Pathematology 2020;21:133–4. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Han GH, Ji SB. Analysis of the therapeutic effect of levodopa combined with pramipexole and its effect on improving motor function in patients with Parkinson's disease. J North Pharm 2018;15:86–7. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Jiang GC. Clinical effects observation of pramipexole and levodopa in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Contemp Med 2015;21:133–4. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Li X. Clinical curative effect and safety of pramipexole combined with levodopa in treatment of Parkinson's disease. Smart Healthcare 2019;5:59–60. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Liu DY. Effects of levodopa and pramipexole on clinical efficacy and motor function in the treatment of patients with Parkinson's disease. J North Pharm 2019;16:92–3. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Liu XZ. Clinical effect of levodopa combined with pramipexole in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Chin Foreign Med Res 2019;17:52–4. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Long X, Bao YM. Efficacy and safety of pramipexole in adjuvant treatment of Parkinson's disease. Chin Foreign Med Res 2019;17:25–7. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lv J. Efficacy and safety of pramipexole combined with levodopa in Parkinson's disease. Clin J Med Offic 2017;45:53–5. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Meng FH. Study on the clinical efficacy and safety of pramipexole in patients with Parkinson's disease. Chin J Mod Drug Appl 2016;10:141–2. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Shen HJ. Efficacy and mechanisms of levodopa combined with pramipexole in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Contemp Med 2019;25:135–7. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Sun SW. Effects of pramipexole combined with levodopa on clinical symptoms and negative emotions in patients with advanced Parkinson's disease. Chin J Pract Nerv Dis 2017;20:118–20. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Teng WL, Sun CL, Yang J, et al. Clinical analysis of levodopa combined with pramipexole in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. J China Prescrip Drug 2017;15:78–9. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wang L. Clinical efficacy and safety of levodopa plus pramipexole in the treatment of patients with Parkinson's disease. Guide China Med 2017;15:65–6. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Wang YY. Clinical observation of pramipexole combined with levodopa in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Chin J Med Guide 2014;16:88–90. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Xu CY, Zhan XP, Wu ZZ. Combined therapeutic effects of levodopa and pramipexole in patients with Parkinson's disease. Med Equip 2019;32:132–3. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Yang RM. Clinical analysis of efficacy of pramipexole combined with levodopa in patients with Parkinson's disease. China J Pharm Econ 2017;12:60–2. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Zhang L. Investigation on clinical efficacy of pramipexole combined with levodopa in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Chin J Ration Drug Use 2019;16:142–4. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zhang Y. Clinical evaluation of therapeutic effect of pramipexole combined with levodopa in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. J China Prescrip Drug 2018;16:03–4. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Jiang DQ, Li MX, Jiang LL, et al. Comparison of selegiline and levodopa combination therapy versus levodopa monotherapy in the treatment of Parkinson's disease: a meta-analysis. Aging Clin Exp Res 2020;32:769–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Huang L, Deng M, He Y, et al. β-asarone and levodopa co-administration increase striatal dopamine level in 6-hydroxydopamine induced rats by modulating P-glycoprotein and tight junction proteins at the blood-brain barrier and promoting levodopa into the brain. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2016;43:634–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Hinterberger H, Andrews CJ. Catecholamine metabolism during oral administration of levodopa. Arch Neurol 1972;26:245–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Mizuno Y, Shimoda S, Origasa H. Long-term treatment of Parkinson's disease with levodopa and other adjunctive drugs. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2018;125:35–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Perez-Lloret S, Rey MV, Ratti L, et al. Pramipexole for the treatment of early Parkinson's disease. Expert Rev Neurother 2011;11:925–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Yasui N, Sekiguchi K, Hamaguchi H, et al. The effect of pramipexole on depressive symptoms in Parkinson's disease. Kobe J Med Sci 2011;56:E214–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Asanuma M, Miyazaki I, Diaz-Corrales FJ, et al. Pramipexole has ameliorating effects on levodopa-induced abnormal dopamine turnover in Parkinsonian striatum and quenching effects on dopamine-semiquinone generated in vitro. Neurol Res 2005;27:533–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Hauser RA, Schapira AH, Barone P, et al. Long-term safety and sustained efficacy of extended-release pramipexole in early and advanced Parkinson's disease. Eur J Neurol 2014;21:736–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Shen T, Ye R, Zhang B. Efficacy and safety of pramipexole extended-release in Parkinson's disease: a review based on meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Neurol 2017;24:835–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]