Abstract

Rapid molecular assays for the detection of mutations associated with rifampin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis are commercially available. However, they are complex and expensive and have predictive values of 90 to 95%. Molecular assays for other drugs are less predictive of resistance. Ideally, assays based on phenotypic markers should be used for susceptibility testing, but these can take weeks to complete. We previously described a rapid phenotypic assay, the phage amplified biologically (PhaB) assay, for the rapid determination of rifampin and isoniazid susceptibility in clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis. In this study, we extended the assay to the study of ethambutol, pyrazinamide, streptomycin, and ciprofloxacin. After the optimization of antibiotic concentrations and incubation conditions, the assay was applied to each drug for a total of 157 isolates. The correlations between the results of the PhaB assay and the resistance ratio method were 94% for isoniazid, 96% for streptomycin, 100% for ciprofloxacin, 88% for ethambutol, and 87% for pyrazinamide. For ciprofloxacin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide, significantly better correlations were found when a 90% reduction in plaque count was used as the cutoff. Turnaround times for the PhaB assay were 2 to 3 days, compared with 10 days for the resistance ratio method. We believe that this low-cost assay may have widespread applicability for the rapid screening of drug resistance in M. tuberculosis isolates, especially in developing countries.

Tuberculosis (TB) is the leading cause of death due to an infectious agent. It affects one-third of the world's population, and 95% of the disease burden is borne by developing countries (11), whose economic and health care infrastructures are often ill equipped to meet the demands placed upon them (14). This situation is likely to deteriorate in the future, with annual disease rates expected to rise from 8.8 million in 1995 to 11.9 million per year in 2005 (13). Superimposed on this is the growing burden of human immunodeficiency virus infection, currently estimated at nearly 31 million people (21), and the potential for both reactivation and exogenous reinfection in patients coinfected with TB and human immunodeficiency virus (17). As TB incidence has increased, there has been a corresponding rise in the proportion of drug-resistant cases, acquired largely as a result of incomplete treatment regimens but also as a result of spread from index cases of resistant TB (12). The most worrisome trend is the increase in multidrug-resistant TB, i.e., resistance to at least isoniazid and rifampin (6). Recent data suggest median acquired rates as high as 36% in some regions (12). One of the major factors influencing the clinical outcome of and the control of the transmission of multidrug-resistant TB from patients is the time taken to obtain drug susceptibility data (19). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend that all isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis be tested for their susceptibility to antibiotics, using the most rapid methods possible, and that susceptibility data for first-line drugs be available within 30 days of receipt of a specimen (18). Conventional culture-based techniques for susceptibility testing take several weeks to complete, and although both radiometric and nonradiometric liquid culture systems have significantly reduced turnaround times, results are still not available for 5 to 12 days after receipt of an isolate (1, 16). Rapid phenotypic methods have a potential advantage, in that they can be applied to susceptibility testing of any drug that inhibits the phenotypic marker being studied. One of the most promising approaches has been in the use of mycobacteriophages to demonstrate the viability of mycobacterial cells. For example, the recombinant mycobacteriophage phAE40 carries the firefly luciferase gene under the control of a strong mycobacterial promoter (hsp 60), and this has been used to transfect M. tuberculosis (luciferase reporter phage [LRP] assay) and demonstrate a loss of light output in the presence of antimicrobial drugs (10). In 1979, David et al. described the lytic cycle of mycobacteriophage D29 in both M. tuberculosis and the rapidly growing Mycobacterium smegmatis (5). In M. smegmatis, the lytic cycle is completed within 90 min, whereas lysis takes approximately 13 h in M. tuberculosis. Wilson et al. developed the phage amplified biologically (PhaB) assay, using D29 to detect viable M. tuberculosis, and they demonstrated that rifampin blocked productive infection in sensitive but not resistant strains (20). A phagicidal agent was used to neutralize extracellular viruses, and infected M. tuberculosis cells were demonstrated by the production of plaques on a lawn of M. smegmatis. The PhaB assay has been compared with both rapid molecular assays (18) and reverse transcriptase PCR (6a) for the rapid diagnosis of rifampin resistance in M. tuberculosis.

In this study, we evaluated the use of the PhaB assay for screening for resistance to isoniazid, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, streptomycin, and ciprofloxacin in clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolates.

Clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis were obtained from clinical specimens cultured on-site at the Public Health Laboratory Service Mycobacterium Reference Unit or subcultured from strains stored in our archives. They were identified by conventional biochemical methodology (3), and for the majority of isolates, identities were also confirmed by DNA probe (AccuProbe; GenProbe, Inc., San Diego, Calif.). Isolates were subcultured on Lowenstein-Jensen egg medium at 37°C.

Preparation of isolates and exposure to drug.

A 1-μl plastic loopful, containing approximately 106 organisms of a mycobacterial isolate, was transferred from growth on Lowenstein-Jensen slopes to a 25-ml plastic screw-cap universal container containing 1 ml of acid-washed glass beads (1 to 4 mm in diameter) in 1 ml of 7H9 broth (Becton Dickinson, Oxford, United Kingdom) with 10% (vol/vol) oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase (OADC) enrichment (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) and 1 mM CaCl2. Organisms were vortexed for 20 s on the maximum speed setting, and an additional 4 ml of 7H9 medium was added. The homogenate was allowed to stand for 15 to 20 min to allow larger clumps to settle. One milliliter of supernatant was transferred to plastic universal containers containing aliquots of antibiotic stock solution to yield the working concentrations. Control samples consisting of 1 ml of the same organism suspension without antibiotic were included.

Preparation of phage D29 suspension.

A plate lysate of D29 was prepared by the standard plate lysate method as described previously (20). The titers of the phage stock were determined by pipetting 10-μl aliquots of 10-fold dilutions onto a lawn of M. smegmatis. Phage stock, containing approximately 109 PFU per ml, was stored at 4°C in 7H9-glycerol-CaCl2 and 10% (vol/vol) OADC with 0.05% (wt/vol) sodium azide. Prior to the PhaB assay, the phage suspension was diluted 100-fold in 7H9-glycerol-CaCl2 and 10% (vol/vol) OADC.

PhaB assay.

The PhaB assay was performed as described by Wilson et al. (20). After samples had been incubated at 37°C, with or without antibiotic, 100 μl of phage D29 suspension was added to each tube. Positive and negative controls containing 1 ml of dilute M. smegmatis (about 105 organisms) and broth only, respectively, were included to assess the integrity of the phage and the effectiveness of the phagicidal agent (phagicide control), respectively. The test and control tubes were incubated for 3 h at 37°C, which corresponds to the absorption and uptake time for D29 with M. tuberculosis (5, 20). Extracellular phage was neutralized by adding 100 μl of 4% (wt/vol) ferrous ammonium sulfate (FAS) and hexahydrate (Sigma-Aldrich, Ltd., St. Louis, Mo.) to each sample, followed by thorough mixing and incubation at room temperature for 5 min before addition of 9 ml of 7H9-glycerol-CaCl2 and 10% (vol/vol) OADC. Samples were incubated for an additional 3 h at 37°C to allow the replication of intracellular phage. Finally, 1 ml of each sample was added to a sterile petri dish with 1 ml of stationary phase M. smegmatis and 9 ml of molten Lemco broth (at 52°C) containing 1% (wt/vol) Bacto Agar (Difco). Immediately before pouring, 1 mM CaCl2 and 10% (vol/vol) OADC were added. On pouring, plates were rotated several times, both clockwise and counterclockwise, to facilitate the mixing of phage-infected cells and M. smegmatis. Plates were allowed to set, and then they were incubated for 18 h at 37°C in plastic bags before readings were taken. When the M. smegmatis growth was insufficiently dense to allow the visualization of the plaques, the incubation period was extended to 24 h. The remaining FAS-treated samples were stored at 4°C.

Resistance ratio method.

Susceptibility testing of the clinical isolates to isoniazid, ethambutol, streptomycin, and ciprofloxacin was performed by the resistance ratio method as described by Collins et al. (3). Pyrazinamide susceptibility testing was carried out by a the modification of Marks' “stepped pH” method (3).

Antibiotic solutions.

Antibiotic stock solutions were made up as follows. Isoniazid (Sigma-Aldrich, Poole, United Kingdom), streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich), and ethambutol (Sigma-Aldrich) were all made up as 1-mg/ml stock solutions in sterile distilled water and stored at 4°C. Ciprofloxacin (Bayer, Newbury, United Kingdom) was made up as a 10-mg/ml stock solution in sterile distilled water and stored at −20°C. Pyrazinamide (Sigma-Aldrich) was made up as a 2.2-mg/ml stock solution and stored at −20°C.

RESULTS

Initial evaluation.

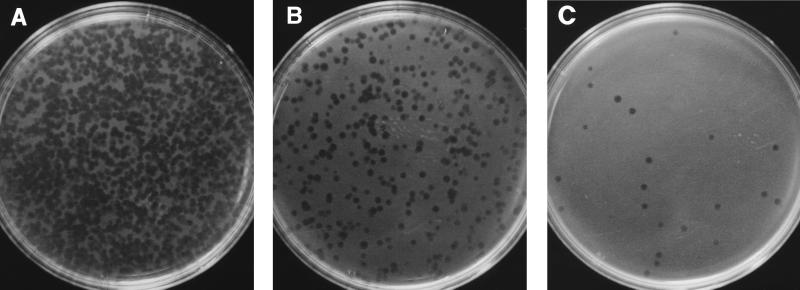

The PhaB assay was performed on stored cultures of M. tuberculosis with known drug susceptibility patterns, determined by the resistance ratio method. After exposure of the drug-susceptible and -resistant isolates to each drug at several concentrations over 24 to 48 h, the mean reductions in the plaque counts obtained in the PhaB assay were compared with the results of the resistance ratio method. The results are summarized in Table 1. The optimum incubation times were 24 h for streptomycin and 48 h for the other four agents. The concentrations of each drug providing discrimination between resistant and susceptible isolates were as follows: 0.8 μg/ml for isoniazid, 16 μg/ml for ethambutol, 8 μg/ml for streptomycin, and 8 μg/ml for ciprofloxacin. The initial evaluation with pyrazinamide at 160 μg/ml was performed at pH 7.4 and 5.5. At the latter pH, neutralization with sodium hydroxide was compared with a wash step. There was little or no effect of the antibiotic on the plaque counts (and hence viable organisms) for pyrazinamide-susceptible mycobacteria after exposure at pH 7.4. Mean reductions in plaque counts were much greater when susceptible isolates were incubated for 48 h at pH 5.5, but only when the cells were washed before the addition of phage. The addition of NaOH, to raise the pH after antibiotic exposure, appeared to reduce the viricidal effect of FAS (Table 1). The initial evaluation of ethambutol showed a possible inhibitory effect of 1 mM CaCl2 on the assay. This was excluded during the ethambutol exposure step during subsequent evaluations. Plates from the PhaB assay are shown in Fig. 1.

TABLE 1.

Preliminary results of PhaB assay

| Antibiotic | Exposure time (h) | Concn (μg/ml) | Mean % reduction in no. of plaques | Result by resistance ratio method | No. of isolates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethambutol | 72 | 4 | 88 | Sensitive | 7 |

| 72 | 8 | 94 | Sensitive | 7 | |

| 48 | 8 | 90 | Sensitive | 10 | |

| 48 | 16 | >99 | Sensitive | 4 | |

| 48 | 16 | 67 | Resistant | 4 | |

| Isoniazid | 24 | 0.8 | 79 | Sensitive | 5 |

| 48 | 0.8 | >99 | Sensitive | 7 | |

| 48 | 0.8 | 34 | Resistant | 3 | |

| Streptomycin | 48 | 8 | >99 | Sensitive | 11 |

| 24 | 8 | >99 | Sensitive | 8 | |

| 24 | 16 | >99 | Sensitive | 6 | |

| 24 | 16 | 5 | Resistant | 2 | |

| 24 | 16 | 90 | Borderline | 1 | |

| 24 | 16 | 95 | Borderline | 1 | |

| Ciprofloxacin | 48 | 4 | 95 | Sensitive | 10 |

| 48 | 4 | 86 | Resistant | 1 | |

| 48 | 8 | 98 | Sensitive | 10 | |

| 48 | 8 | 67 | Resistant | 1 | |

| Pyrazinamide | 48 (pH 7.4) | 160 | 38 | Sensitive | 12 |

| 48 (pH 5.5) | 80 | 31 | Sensitive | 5 |

FIG. 1.

Photographs of plates from the PhaB assay performed on 10-fold dilutions of M. smegmatis demonstrating an approximate 10-fold reduction in the number of plaques produced at each dilution. (A) One milliliter of a 48-h broth culture of M. smegmatis was diluted 100-fold in 7H9 broth, and the PhaB assay was performed on a 1-ml sample as described previously. Samples of 1 ml were further diluted 1/10 (B) and 1/100 (C) prior to PhaB assay.

Further evaluation with clinical isolates.

The PhaB assay was performed on clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis referred to the Mycobacterium Reference Unit for susceptibility testing. Isolates were chosen such that the study could include the maximum number of strains resistant to each drug, and some multidrug-resistant isolates were tested by the PhaB assay with more than one agent. In total, 156 clinical isolates were used, and the utility of the PhaB assay was determined with 51 isolates for isoniazid and 50 isolates for each of the other drugs. Drug concentrations and assay conditions were as follows: isoniazid at 0.8 μg/ml for 24 h, streptomycin at 8 μg/ml for 24 h, ethambutol at 16 μg/ml for 48 h, pyrazinamide at 160 μg/ml for 48 h at pH 5.5, and ciprofloxacin at 8 μg/ml for 48 h. Isolates were scored sensitive by the PhaB assay if there was a 99% or greater reduction in the plaque count in the presence of the drug. Results were also calculated by using a 90% or greater reduction in the plaque count to assess which cutoff discriminated better between susceptible and resistant strains. The concordance between the PhaB assay and the resistance ratio method for the initial testing of each drug is shown in Tables 2 to 6.

TABLE 2.

Concordance between results of PhaB assay with isoniazid at 0.8 μg/ml for 48 h and resistance ratio method

| PhaB assay result | No. of isolates with resistance ratio method result ofa:

|

% Concordance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitive | Resistant | ||

| 99% cutoff (n = 51) | |||

| Sensitive | 31 | 1 | |

| Resistant | 2 | 17 | 94 |

| 90% cutoff (n = 51) | |||

| Sensitive | 33 | 1 | |

| Resistant | 0 | 17 | 98 |

Results after 10 to 21 days, using a cutoff of 0.2 μg/ml in egg medium.

TABLE 6.

Concordance between results of PhaB assay with ciprofloxacin at 8 μg/ml for 48 h and resistance ratio method

| PhaB assay result | No. of isolates with resistance ratio method result ofa:

|

% Concordance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitive | Resistant | ||

| 99% cutoff (n = 39) | |||

| Sensitive | 11 | 0 | |

| Resistant | 23 | 5 | 47 |

| 90% cutoff (n = 42) | |||

| Sensitive | 37 | 0 | |

| Resistant | 0 | 5 | 100 |

Results after 10 to 21 days, using a cutoff of 5 μg/ml.

One isoniazid-resistant isolate gave a susceptible result for the PhaB assay, when a 99% reduction in plaque numbers was used, for both initial and repeat testing. One streptomycin-resistant isolate also gave an incorrect sensitive result at the above cutoff. This strain was initially borderline resistant by the resistance ratio method, but on retesting it was shown to be low-level resistant (resistance ratio of 4) (9).

Out of 251 PhaB assays performed, 20 (8%) failed to give a result on initial testing due to inadequate plaque numbers on the control plates. Of these, three isolates were contaminated with environmental bacteria and the remaining 17 were concordant with the resistance ratio method on retesting, apart from one ethambutol-resistant isolate which was incorrectly scored as sensitive; i.e., there was a >90% reduction in the plaque count in the presence of the drug.

DISCUSSION

The PhaB assay was developed by Wilson et al. and was applied to rifampin and isoniazid susceptibility testing in clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis (20). In the present study, we demonstrated that this methodology can be used, with minor modifications, as a rapid screen for antimicrobial resistance not only to isoniazid but also to ethambutol, pyrazinamide, streptomycin, and ciprofloxacin. The total time taken to determine susceptibility to streptomycin was 48 h. The turnaround time for the other agents was 72 h, i.e., 1 week less than with the resistance ratio method on solid media. Streptomycin consistently achieved a 99% reduction in plaque counts after only a 24-h exposure. This is consistent with data from another mycobacteriophage-based assay, the LRP assay, in which a 99% reduction in the light signal was seen after an overnight incubation of susceptible isolates with streptomycin (16). In the PhaB assay, exposure of cells to isoniazid, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, and ciprofloxacin for 48 h is recommended, which is also consistent with the LRP assay (15). The differences in the exposure times required are likely to reflect differences in the modes of action of the agents, such as streptomycin and rifampin, which act on transcription and translation (cell processes vital to the support of a lytic cycle), and those such as isoniazid and ethambutol, which act on the cell wall (10).

The results of the streptomycin and isoniazid susceptibility testing by the PhaB assay were highly concordant with the results of the resistance ratio method, the conventional, culture-based methodology used by the United Kingdom reference laboratory. Reductions in plaque counts on antibiotic-treated plates that were greater than 99% from those on untreated plates were used by the PhaB assay as the cutoff points for defining resistance (20). For ethambutol, ciprofloxacin, and pyrazinamide, a 99% reduction in the plaque counts of drug-treated organisms was rarely obtained, and a 90% reduction discriminated better between susceptible and resistant strains. The sensitivity and specificity, respectively, of the assay for the detection of resistance in clinical isolates (including repeat testing of isolates for which no result was obtained on initial testing) were 94 and 94% for isoniazid (99% plaque reduction), 90 and 100% for streptomycin (99% plaque reduction), 100 and 100% for ciprofloxacin (90% plaque reduction), 92 and 70% for pyrazinamide (90% plaque reduction), and 94 and 75% for ethambutol (90% plaque reduction).

Relatively high antibiotic breakpoints were used in this study, compared with concentrations recommended for methods which measure growth over a much longer time course (3, 9). Other rapid phenotypic assays have utilized high breakpoint concentrations; for instance, Ryan et al. detected relatively low numbers of isoniazid-resistant mutants in a mixed population of Mycobacterium bovis BCG by gel microdrop encapsulation (16). The organisms were incubated with 5 μg of isoniazid per ml for 4 days, and the assay revealed that 3% of the population was resistant, although no difference could be demonstrated when only 1% of the population was resistant. Although cells were exposed to a lower concentration of antibiotic for less time in the PhaB assay, it was still possible that, with high breakpoint concentrations, isolates with borderline or low-level resistance may have been missed. However, the good correlation with the resistance ratio method results suggests that these isolates are relatively uncommon in our laboratory. High concentrations of antibiotics may also affect different cellular targets. This may have been the case with ethambutol, which, at lower concentrations, is regarded as a bacteriostatic agent both in vitro (8) and in a macrophage model (4). The reductions in plaque counts of greater than 90%, seen with the majority of susceptible isolates with 16 μg of ethambutol per ml over 48 h, were incompatible with a bacteriostatic effect alone. As the doubling time for M. tuberculosis is 18 to 24 h (9), at most only a sixfold difference would be expected between untreated and antibiotic-treated mycobacteria during exposure, which suggests that the antibiotic is bactericidal at higher concentrations. This is consistent with the observations of others who demonstrated that a pulsed exposure of susceptible M. tuberculosis to 10 μg of ethambutol per ml for 96 h resulted in a 4-log reduction in CFU counts (7) and that ethambutol has a moderate early bactericidal effect in vivo (2). Nevertheless, a good correlation with the resistance ratio method was found, so any effect of ethambutol on the ability of D29 to infect resistant strains was not significant.

This method is easy to perform and presents a low-cost, reliable means of screening for antimicrobial resistance in clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis. In addition, the limited capital outlay and training required make this an assay suitable for use in developing countries.

TABLE 3.

Concordance between results of PhaB assay with streptomycin at 8 μg/ml for 24 h and resistance ratio methoda

| PhaB assay result | No. of isolates with resistance ratio method result ofa:

|

% Concordance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitive | Resistant | ||

| 99% cutoff (n = 50) | |||

| Sensitive | 39 | 1 | |

| Resistant | 0 | 10 | 98 |

| 90% cutoff (n = 50) | |||

| Sensitive | 39 | 2 | |

| Resistant | 0 | 9 | 96 |

Results after 10 to 21 days, using a cutoff of 40 μg/ml in egg medium.

TABLE 4.

Concordance between results of PhaB assay with ethambutol at 16 μg/ml for 48 h and resistance ratio method

| PhaB assay result | No. of isolates with resistance ratio method result ofa:

|

% Concordance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitive | Resistant | ||

| 99% cutoff (n = 42) | |||

| Sensitive | 7 | 0 | |

| Resistant | 20 | 15 | 53 |

| 90% cutoff (n = 43) | |||

| Sensitive | 23 | 0 | |

| Resistant | 5 | 15 | 88 |

Results after 10 to 21 days, using a cutoff of 3.2 μg/ml in egg medium.

TABLE 5.

Concordance between results of PhaB assay with pyrazinamide at 160 μg/ml (pH 5.5) for 48 h and conventional methodology

| PhaB assay result | No. of isolates with stepped pH method result ofa:

|

% Concordance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitive | Resistant | ||

| 99% cutoff (n = 35) | |||

| Sensitive | 11 | 0 | |

| Resistant | 15 | 9 | 57 |

| 90% cutoff (n = 43) | |||

| Sensitive | 27 | 1 | |

| Resistant | 5 | 12 | 87 |

Yates's adaption of Marks's stepped pH method after 10 to 21 days, using a cutoff of 66 μg/ml.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bergmann J S, Woods G L. Evaluation of the ESP culture system II for testing susceptibilities of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates to four primary antituberculous drugs. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2940–2943. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.2940-2943.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Botha F J, Sirgel F A, Parkin D P, van de Wal B W, Donald P R, Mitchison D A. Early bactericidal activity of ethambutol, pyrazinamide and the fixed combination of isoniazid, rifampicin and pyrazinamide (Rifater) in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. S Afr Med J. 1996;86:155–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins C H, Grange J M, Yates M D. Tuberculosis bacteriology: organization and practice. Oxford, England: Butterworth Heinemann; 1997. pp. 98–110. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crowle A J. Studies of antituberculous chemotherapy with an in vitro model of human tuberculosis. Semin Respir Infect. 1986;1:262–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.David H L, Clavel S, Clement F. Absorption and growth of the bacteriophage D29 in selected mycobacteria. Ann Virol. 1979;131:167–184. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drobniewski F A. Is death inevitable with multiresistant TB plus HIV infection? Lancet. 1997;349:71–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)60878-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6a.Eltringham I J, Drobniewski F A, Mangan J A, Butcher P D, Wilson S M. Evaluation of reverse transcription-PCR and a bacteriophage-based assay for rapid phenotypic detection of rifampin resistance in clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3524–3527. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.11.3524-3527.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gangadharam P R, Pratt P F, Perumal V K, Iseman M D. The effects of exposure time, drug concentration, and temperature on the activity of ethambutol versus Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;141:1478–1482. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/141.6.1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gangadharam P R. Drug resistance in mycobacteria. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press; 1984. pp. 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heifets L B. Drug susceptibility in the chemotherapy of mycobacterial infections. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1991. pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobs W R, Jr, Barletta R G, Udani R, Chan J, Kalkut G, Sosne G, Kieser T, Sarkis G J, Hatful G, Bloom B R. Rapid assessment of drug susceptibilities of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by means of luciferase reporter phages. Science. 1993;260:819–822. doi: 10.1126/science.8484123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Narain J P, Raviglione M C, Kochi A. HIV associated tuberculosis in developing countries: epidemiology and strategies for prevention. Tuber Lung Dis. 1992;73:311–321. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(92)90033-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pablos-Mendez A, Raviglione M C, Laszlo A. Global surveillance for antituberculous drug resistance, 1994–1997. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1641–1649. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199806043382301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raviglione M C, Snider D E, Kochi A. Global epidemiology of tuberculosis. JAMA. 1995;223:220–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raviglione M C, Dye C, Schmidt S, Kochi A. Assessment of worldwide tuberculosis control. Lancet. 1997;350:624–629. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)04146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riska P F, Jacobs W R., Jr The use of luciferase-reporter phage for antibiotic-susceptibility testing in mycobacteria. Methods Microbiol. 1998;101:431–455. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-471-2:431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryan C, Nguyen B-T, Sullivan S J. Rapid assay for mycobacterial growth and antibiotic susceptibility using gel microdrop encapsulation. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1720–1726. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.7.1720-1726.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Styblo K. The impact of HIV infection on the global epidemiology of tuberculosis. Bull Int Union Tuberc Lung Dis. 1991;66:27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tenover F C, Crawford J T, Huebner R E, Geiter L J, Horsburgh C R, Jr, Good R C. The resurgence of tuberculosis: is your laboratory ready? J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:767–770. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.4.767-770.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wenger P N, Otten J, Breeden A, Orfas D, Beck-Sague C M, Jarvis W R. Control of nosocomial transmission of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Lancet. 1995;345:235–240. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90228-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson S M, Al-Suwaidi Z, McNerney R, Drobniewski F A. Evaluation of a new rapid bacteriophage-based method for the drug susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat Med. 1997;3:465–468. doi: 10.1038/nm0497-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-data as at 30 June 1996. Weekly Epidemiol Rec. 1996;71:205–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]