Abstract

Current antibody testing for human granulocytic ehrlichiosis relies predominantly on indirect fluorescent-antibody assays and immunoblot analysis. Shortcomings of these techniques include high cost and variability of test results associated with the use of different strains of antigens derived from either horses or cultured HL-60 cells. We used recombinant protein HGE-44, expressed and purified as a maltose-binding protein (MBP) fusion peptide, as an antigen in a polyvalent enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Fifty-five normal serum samples from healthy humans served as a reference to establish cutoff levels. Thirty-three of 38 HGE patient serum samples (87%), previously confirmed by positive whole-cell immunoblotting, reacted positively in the recombinant ELISA. In specificity analyses, serum samples from patients with Lyme disease, syphilis, rheumatoid arthritis, and human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME) did not react with HGE-44–MBP antigen, except for one sample (specificity, 98%). We conclude that recombinant HGE-44 antigen is a suitable antigen in an ELISA for the laboratory diagnosis and epidemiological study of HGE.

Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE) is an emerging tick-borne infection in North America and Europe and has been recognized increasingly as a cause of acute febrile illness in tick-infested areas (5, 12, 20). The bacterium that causes HGE is transmitted by the same ticks (Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus in the United States and Ixodes ricinus in Europe) that are also responsible for the transmission of Borrelia burgdorferi or Babesia spp., the agents of Lyme disease and human babesiosis, respectively (3, 19, 23). Therefore, patients who have been diagnosed with one tick-associated illness are at an increased risk for another tick-borne infection (13, 16).

The cultivation of the HGE agent in HL-60 cells has facilitated investigations of this gram-negative intracellular organism (7). Several immunoreactive proteins have been identified and characterized (1, 10, 11, 25), and some of the genes encoding these proteins have been cloned (9, 18, 22, 24). The hge-44 gene family encodes several proteins that are thought to be located on the bacterial membrane surface and are most frequently recognized by antibodies in sera from HGE patients (9, 11, 18, 24). Antibody testing for HGE is currently performed by using indirect fluorescent-antibody (IFA) staining methods, immunoblot analysis, an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), or a dot blot assay (11, 16, 21, 24). Disadvantages of the three former techniques include high cost and variability of test results associated with the use of different strains of antigens derived from either horses or cultured HL-60 cells (1, 17). Since the HGE-44 proteins are readily recognized by sera from most HGE patients, the use of recombinant HGE-44 antigen for an automated diagnostic ELISA may reduce cost and variability of results and provide a method for screening large numbers of patient sera. We report in this paper on the development and use of an ELISA with recombinant HGE-44 antigen for the serodiagnosis of HGE.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient sera.

Thirty-eight sera from 36 patients with HGE were collected by physicians collaborating in the Yale–Connecticut Department of Public Health emerging infections program. All patients fulfilled the criteria of having an acute febrile illness, headache, and malaise, while the majority had laboratory findings of leukopenia and/or thrombocytopenia. The patients were all diagnosed with HGE based on clinical signs and symptoms and either the identification of morulae in a peripheral blood smear or a positive PCR result, and all had a positive whole-cell lysate HGE immunoblot result (11). Twelve sera from 12 patients with a documented infection with Ehrlichia chaffeensis (identification of morulae and by IFA testing) were used for specificity studies; these sera were kindly provided by J. G. Olson, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga., and by the Connecticut Department of Public Health. These sera were previously documented by IFA testing to have positive antibody titers for E. chaffeensis antigen (1:80 or greater) and negative results for Ehrlichia equi (positive titer, 1:80 or greater). All 12 sera were tested by immunoblotting with a whole-cell lysate antigen of the HGE agent, and none of them was reactive. Twenty-four sera from 24 patients with Lyme disease were tested at the Lyme Reference Laboratory at Yale University and at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station. Testing procedures were based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria (2). Of those 24 sera, 8 sera were reactive in immunoblotting with whole-cell lysate ehrlichial antigens and were excluded from specificity analyses. Sixteen sera from 16 patients diagnosed with syphilis were provided by the Connecticut Department of Public Health and tested for antibodies to Treponema pallidum. One serum found to have antibodies to the HGE agent by immunoblotting was excluded from specificity analyses. Seven sera from seven patients with rheumatoid arthritis were tested by rheumatologists at Yale University, and all seven sera were positive for rheumatoid factor. None of these samples was reactive in immunoblotting for HGE.

A total of 55 sera from 55 healthy blood donors were used as a reference group to test antibody reactivity in an ELISA with HGE-44–maltose-binding protein (MBP) as an antigen and MBP as a control. The 55 sera were tested by whole-cell lysate immunoblotting, and all but 3 sera were nonreactive. The three reactive samples were not excluded from the reference group.

Informed consent, in accordance with institutional review board approval, was obtained for these studies.

Preparation of HGE-44–MBP.

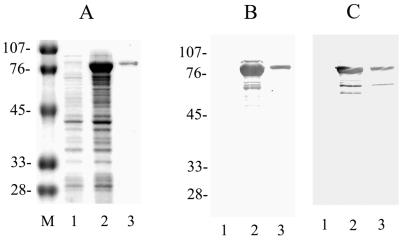

The hge-44 gene sequence that was used to generate recombinant HGE-44 protein has been published previously (9). To improve the solubility of the recombinant protein, glutathione transferase (GT) was replaced by MBP as a fusion partner. The DNA fragment was generated by double digestion of hge-44-pMX with EcoRI and XhoI, releasing a 1,290-bp fragment, and was inserted into the pMAL-c2X vector downstream of the Escherichia coli malE gene, which encodes MBP, resulting in the expression of an MBP fusion protein (pMAL protein fusion and purification system; New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.). Transformed cells (XL-1 blue; Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) were grown to a concentration of 2 × 108 cells/ml, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added (final concentration, 0.3 mM), and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 20 min and were lysed by overnight freezing at −20°C and by subsequent sonication for 10 min. Expression in E. coli produced a soluble fusion protein of about 80 kDa on a Coomassie blue-stained gel (Fig. 1A); the protein was purified on an affinity column as suggested by the protocol of the manufacturer (New England Biolabs). HGE-44–MBP was recognized by rabbit anti-MBP serum (Fig. 1B) and patient serum (Fig. 1C) in an immunoblot analysis. Similarly, MBP was purified for use as a control in an ELISA (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

HGE-44–MBP protein synthesis and immunoblot analysis. (A) Coomassie blue stain of an E. coli lysate containing HGE-44–MBP (lane 1, uninduced; lane 2, induced; lane 3, affinity-purified HGE-44–MBP). Lane M, size markers (kilodaltons). (B) Immunoblot of the gel in panel A probed with rabbit anti-MBP serum. (C) Immunoblot of the gel in panel A probed with serum from an HGE patient.

ELISA.

The ELISA was a solid-phase noncompetitive method similar to that used for the detection of antibodies to whole-cell or recombinant B. burgdorferi antigens (14, 15). Ninety-six-well flat-bottom polystyrene plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated by adding in alternate rows 50 μl of antigen (HGE-44–MBP diluted in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]; final concentration, 2.5 μg/ml) or PBS only (PBS control). Similarly, control plates were coated by adding in alternate rows 50 μl of MBP in PBS (final concentration, 2.5 μg/ml) or PBS only (PBS control). The plates were incubated uncovered overnight at 37°C. On the next day, the plates were blocked with PBS containing 0.5% horse serum (200 μl per well) at 37°C for 90 min. Human sera were serially diluted twofold (starting at a dilution of 1:80) with diluent (1 liter of diluent contains 376 ml of 10× PBS, 2 ml of Tween, 564 ml of distilled water, 50 ml of horse serum, and 10 ml of 5% dextran sodium sulfate). After blocking, the plates were washed five times with PBS–0.05% Tween. Diluted sera (60 μl/well) were added to wells coated with HGE-44–MBP, MBP alone, or PBS only and incubated for 60 min. The plates were washed five times. Subsequently, 60 μl of polyvalent horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Kierkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Inc. [KPL], Gaithersburg, Md.) (1:12,000 dilution in diluent) was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. After the plates were washed five times, 60 μl of ABTS (2,2′-azino-di-[3-ethylbenzthiazoline sulfonate]; KPL) was added to each well and incubated at 37°C. After 1 h, absorbances were measured with a plate reader at 405 nm. Optimal concentrations of antigens, serum dilutions, secondary antibody dilutions, and substrate incubation times were established in prior experiments. Net absorbance values were calculated by subtracting MBP values from their respective HGE-44–MBP values after first correcting for the PBS control values for both HGE-44–MBP and MBP. Cutoff values were established based on 2 standard deviations above the mean absorbance in the group of healthy donor sera (n = 55).

Immunoblotting.

All sera were tested by immunoblot analysis with procedures described previously prior to the ELISA testing (11). Briefly, a lysate of ehrlichial bacteria was dissolved in sample buffer (5% 2-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], and 0.8% bromophenol blue in 6.25 mM Tris buffer [pH 6.8], heated for 10 min at 100°C, and loaded onto a gel for SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis separation. Molecular mass standards were used for each panel (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.). Protein was transferred to nitrocellulose, and the blocking procedure was performed by use of PBS with 5% nonfat dry milk. Nitrocellulose strips were incubated with a 1:100 PBS dilution of human sera, washed three times with PBS–0.2% Tween, incubated with the secondary alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antibody, and washed three times with PBS–0.2% Tween. The secondary antibody, alkaline phosphatase-conjugated F(ab′)2 anti-human IgM or IgG (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.), was used as specified by the manufacturer (1:1,000 dilution). Blots were developed for 5 min with nitroblue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (KPL), and the reaction was quenched with distilled water. Immunoblots containing HGE-44–MBP were processed in a similar manner, except that 5 μg of HGE-44–MBP was loaded onto the gel instead of a whole-cell HGE agent lysate.

IFA.

Serologic testing by IFA staining methods was performed as described previously (13, 16). Briefly, slides for IFA testing were coated with HL-60 cells infected with the HGE agent (NCH-1 strain) and fixed by cold acetone treatment. Sera were diluted in PBS solution and tested for total antibodies with a 1:80 dilution of polyvalent fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled goat anti-human immunoglobulin (KPL). Distinct fluorescence of inclusion bodies of infected HL-60 cells was considered evidence of antibody presence in diluted sera (dilution, 1:80 or greater). Twofold dilutions of positive sera were retested to determine the highest serum dilution that was still reactive. Positive and negative control sera were included in all testing.

RESULTS

ELISA.

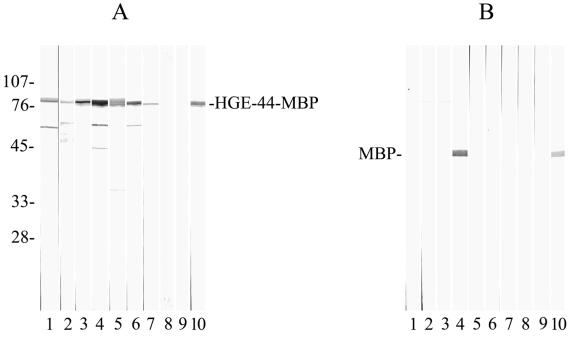

The optical density (OD) values of the 55 sera from the 55 healthy blood donors were used as the reference group to calculate the cutoff levels at different serum dilutions. OD values were considered positive if equal to or greater than 0.45 (1:160 dilution), 0.38 (1:320 dilution), or 0.26 (1:640 dilution or greater). Subsequently, 38 sera from HGE patients (with clinical disease and reactivity to the 44-kDa antigen on immunoblots) were tested in an ELISA. Of these, 33 sera (87%) showed antibody reactivity, with OD values considered positive according to the previously established cutoff levels, while 4 sera had OD values that were below the cutoff levels and were considered nonreactive. One serum sample showed high reactivity to the MBP control antigen (at a titer of ≥1:640) as well as to the HGE-44–MBP antigen (at a titer of ≥1:640); the test result was therefore not interpretable. The four HGE patient sera that failed to react in the ELISA were retested in an ELISA with the same HGE-44–MBP antigen; again, no antibodies were detected, while reactivity was clearly indicated on immunoblots with either HGE-44–MBP (Fig. 2) or the whole-cell HGE agent lysate as the antigen (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

(A) HGE-44–MBP immunoblots probed with sera from patients with HGE. Lanes 1 to 3, HGE patient sera that tested negative in the ELISA; lane 4, HGE serum containing antibodies to MBP; lanes 5 to 7, HGE patient sera that tested positive in the ELISA; lanes 8 and 9, sera from healthy volunteers; lane 10, rabbit serum containing antibodies to MBP (positive control). The molecular mass of HGE-44–MBP is about 80 kDa. (B) Immunoblots containing MBP probed with sera as in panel A. Numbers at left are in kilodaltons.

Next, specificity tests were performed with sera from different study groups, including confirmed Lyme disease, human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME), rheumatoid arthritis, or syphilis (Table 1). A total of 24 sera from subjects with Lyme disease (clinical disease and confirmed by immunoblotting) were randomly selected based on a positive Lyme immunoblot result and then tested by whole-cell HGE agent lysate immunoblotting to exclude possible exposure (concomitant or prior) to the HGE agent. Eight sera showed specific reactivity to ehrlichial proteins in immunoblotting and were excluded from specificity analyses of the HGE ELISA because these sera were considered to have specific antibodies to both B. burgdorferi and the HGE agent. The other 16 sera tested negative in the ELISA (Table 1). Twelve HME patient sera characterized previously by IFA procedures and immunoblotting did not show antibody reactivity in the HGE-44–MBP ELISA. Seven sera from patients with clinical rheumatoid arthritis and positive for rheumatoid factor did not have detectable antibodies to the HGE agent in the ELISA. Of the 16 sera from 16 patients with confirmed syphilis (IFA titer, ≥1:1,024), 15 were nonreactive in whole-cell HGE agent lysate immunoblotting, while 1 was reactive (Table 1). This sample was excluded from the specificity calculations. Of the 15 sera included, 14 did not have detectable antibodies in the ELISA, while the 1 remaining sample was reactive. The reactivity of this sample was interpreted as a false-positive ELISA result. In specificity calculations for the ELISA, based on the analysis of 50 sera from 50 patients with different diseases (16 Lyme disease, 12 HME, 7 rheumatoid arthritis, and 15 syphilis patients), only one syphilitic serum sample showed antibody reactivity, resulting in a specificity of 98%.

TABLE 1.

Antibody reactivity of human sera in the HGE-44–MBP ELISA and a whole-cell HGE agent lysate immunoblot

| Study group | Total no. of sera | No. of sera with the indicated result in:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELISA

|

Immunoblotting

|

||||

| Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | ||

| HGE | 38 | 5a | 33 | 0 | 38 |

| Lyme disease | 24 | 17 | 7b | 16 | 8b |

| HME | 12 | 12 | 0 | 12 | 0 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 7 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| Syphilis | 16 | 14 | 2c | 15 | 1c |

One sample had antibody reactivity to the MBP control antigen and the HGE-44–MBP antigen at a titer of ≥1:640; the result was therefore uninterpretable.

These samples contained antibodies specific for the HGE agent in immunoblotting, so only the 16 immunoblot-negative serum samples were included in the ELISA specificity calculations.

One sample was previously found to have antibodies specific for the HGE agent and was therefore excluded from the ELISA specificity calculations. The other sample did not show reactivity in immunoblotting and was included in the ELISA specificity calculations.

In order to compare the HGE-44-based ELISA with current IFA tests, the 38 sera from the HGE patients also were tested by IFA staining procedures. Twenty-seven sera had evidence of antibodies against the HGE agent, while 11 sera were not reactive in IFA procedures. The calculated sensitivity was 71%. Of the five HGE sera that were found negative in the ELISA but positive in immunoblotting, three were found positive in IFA procedures. For the positive samples in both tests, the calculated geometric mean antibody titers were 753 in the ELISA and 296 in the IFA test, and the titers ranged from 160 to 10,240 and 80 to 2,560, respectively.

DISCUSSION

During the course of an HGE infection, most patients develop antibodies to the 44-kDa family of ehrlichial proteins (1, 11, 25). These HGE-44 proteins are members of a family of related proteins that have molecular masses between 42 and 47 kDa and are encoded by genes which have a high degree of nucleotide similarity in conserved parts of the gene sequence (9, 18, 24). In this paper, we describe the use of HGE-44 as a recombinant protein fused to MBP. The HGE-44–MBP antigen was used in our polyvalent ELISA-based diagnostic test. Thirty-three HGE patients were correctly found to have antibodies to the HGE agent (sensitivity, 87%), while sera from persons with other diseases, such as Lyme disease, HME, rheumatoid arthritis, or syphilis, were normally nonreactive in the HGE ELISA (specificity, 98%). We conclude that the performance of an ELISA with the HGE-44–MBP antigen is comparable to if not better than that of IFA procedures for the laboratory diagnosis of HGE. However, the overall sensitivity needs to be improved further if this recombinant antigen-based test is to be used as a major screening test.

Currently, there is no practical laboratory “gold standard” for the detection of HGE infection, making discordant results from IFA staining methods, immunoblotting, and the HGE-44 ELISA difficult to interpret. We used whole-cell HGE immunoblotting as our standard to define our group of negative controls and to confirm HGE antibody reactivity in the HGE patient group. Although there may be a selection bias in the use of HGE patient sera that contain antibodies to HGE-44 proteins, as detected by immunoblotting, we have found agreement between the results of IFA and immunoblot testing to be in the range of 79 to 87% (8, 16). The observed relatively low sensitivity of IFA testing may be due in part to this selection bias, the HGE strain used, or the conservative grading procedures in the test. Furthermore, occasionally we have observed specific fluorescence of morulae for some sera that showed reactivity on immunoblots to bands in the 70- to 80-kDa range but not to the 44-kDa cluster of bands. Nevertheless, if analyses of larger numbers of sera confirm our findings, then an HGE-44-based ELISA may replace the current serologic IFA testing method that uses whole-cell HGE antigens (4, 17, 21). Variability in IFA test results is the product of interlaboratory differences, use of different ehrlichial strains, and variations associated with separate batches of cultured HGE antigen. Despite these variations, which lead to different sensitivities and specificities, IFA staining procedures have been an acceptable method for the initial screening of sera (17). The advent of an automated HGE-44-based ELISA will reduce some of the sources of variability in the current IFA testing method and may improve the overall performance of HGE antibody testing. However, the development of ELISAs to differentiate class-specific antibodies is needed. Immunoblot analysis should be used to verify ELISA results and to further evaluate the performance of ELISAs.

We identified four HGE patients whose sera did not have detectable antibodies in an ELISA with the HGE-44–MBP antigen, but specific antibodies to 44-kDa proteins were detected by whole-cell immunoblot analysis. The presence of SDS in the immunoblotting procedure may have affected protein folding, resulting in the observed differences. Furthermore, several investigators have reported the cloning and expression of an hge-44 gene homolog. A comparison of the corresponding protein sequences shows a general pattern for all members of this gene family (9, 18, 24). In general, the protein sequences consist of two conserved regions located at the amino terminus and carboxyl terminus and flanking a highly variable middle region. A similar phenomenon has been shown for the genetically related MSP-2 family in Anaplasma marginale (6). Immunoblots with different HGE isolates show different banding patterns when a panel of HGE patient sera is used, indicating that the proteins of the HGE-44 family are differentially expressed (1, 25). The variable banding patterns also indicate that persons have developed different antibody responses depending on which HGE-44 proteins are expressed. Therefore, it is conceivable that an HGE patient may not have antibodies against a certain HGE-44 homolog if that homolog is not expressed during the acute phase of infection. If such a homolog were used as an antigen in a recombinant HGE-44 antigen-based ELISA, then there could be false-negative results. A mixture of two or more recombinant antigens, a strategy that is currently being considered for Lyme disease antibody testing (14, 15), may circumvent this problem and thus improve the overall sensitivity of the assay.

We conducted specificity tests with sera from patients with well-documented diseases, including Lyme disease, syphilis, rheumatoid arthritis, and HME. In defining the Lyme disease group, we found that one third of the Lyme disease sera had antibodies to the HGE agent, as detected by immunoblotting. This result is to be expected because patients with Lyme disease and frequent tick bites probably have a risk of acquiring other tick-associated illnesses, including HGE (13, 16). The number of Lyme disease patients with concomitant ehrlichial and borrelial antibodies is comparable to what has been previously reported (13, 16). Sera containing antibodies specific to both B. burgdorferi and the HGE agent need to be excluded from ELISA specificity analyses for this reason.

The advantage of using MBP rather than glutathione transferase (GT) as a fusion partner is that the HGE-44–MBP antigen is highly soluble and easy to purify, compared to the HGE-44–GT antigen (9). Other investigators have encountered similar difficulties in purifying recombinant HGE-44 proteins in large quantities using a variety of different strategies (18, 24). This result is most likely attributable to the peptide sequence and structure, which dictate the (in)solubility of these membrane proteins. We observed antibodies that reacted to MBP in only 1 serum of a total of 156 sera. Therefore, we suggest that the presence of antibodies to MBP is not a common occurrence. If there is major antibody reactivity to MBP in a patient serum, interpretation may not be possible. It is advised that proper controls be included in all ELISAs to check for false-positive reactions to MBP or other reagents.

Since the first description of HGE in the United States in 1994, the number of reported cases has increased steadily. Accurate laboratory confirmation of suspected HGE infections is important for clinical practice as well as for epidemiological studies of this emerging disease. A recombinant HGE-44 antigen-based ELISA may prove to be an additional diagnostic tool for further determining the incidence and geographic distribution of this disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tia Blevins for technical assistance and James Meek and Robert Ryder (Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, Yale University) for coordinating the emerging infections program.

This work was supported in part by grants (HR8-CCR113382 and U50/CCU111188) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a grant (RO1-AI41440) from the National Institutes of Health, and federal Hatch funds administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. J.W.I. is supported by a fellowship from the L. P. Markey Charitable Trust, and E.F. is a recipient of a clinical scientist award in translational research from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asanovich K M, Bakken J S, Madigan J E, Aguero-Rosenfeld M, Wormser G P, Dumler J S. Antigenic diversity of granulocytic ehrlichia isolates from humans in Wisconsin and New York and a horse in California. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1029–1034. doi: 10.1086/516529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for test performance and interpretation from the Second National Conference on Serologic Diagnosis of Lyme Disease. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1995;44:590–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christova I S, Dumler J S. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Bulgaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:58–61. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Comer J A, Nicholson W L, Olson J G, Childs J E. Serologic testing for human granulocytic ehrlichiosis at a national referral center. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:558–564. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.3.558-564.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dumler J S, Bakken J S. Human ehrlichioses: newly recognized infections transmitted by ticks. Annu Rev Med. 1998;49:201–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.French D M, McElwain T F, McGuire T C, Palmer G H. Expression of Anaplasma marginale major surface protein 2 variants during persistent cyclic rickettsemia. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1200–1207. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.1200-1207.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodman J L, Nelson C, Vitale B, Madigan J E, Dumler J S, Kurtti T J, Munderloh U G. Direct cultivation of the causative agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:209–215. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601253340401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.IJdo, J. W., J. I. Meek, M. L. Cartter, L. A. Magnarelli, C. Wu, S. W. Tenuta, E. Fikrig, and R. W. Ryder. Emergence of another tick-borne infection in the 12-town area around Lyme, Connecticut: human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.IJdo J W, Sun W, Zhang Y, Magnarelli L A, Fikrig E. Cloning of the gene encoding the 44-kilodalton antigen of the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis and characterization of the humoral response. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3264–3269. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3264-3269.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.IJdo J W, Zhang Y, Anderson M L, Goldberg D, Fikrig E. Heat shock protein 70 of the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis binds to Borrelia burgdorferi antibodies. Clin Diagn Lab Med. 1998;5:118–120. doi: 10.1128/cdli.5.1.118-120.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.IJdo J W, Zhang Y, Hodzic E, Magnarelli L A, Wilson M L, Telford S R, Barthold S W, Fikrig E. The early humoral response in human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:687–692. doi: 10.1086/514091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lotric-Furlan S, Petrovec M, Zupanac T A, Nicholson W L, Sumner J W, Childs J E, Strle F. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Europe: clinical and laboratory findings for four patients from Slovenia. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:424–428. doi: 10.1086/514683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magnarelli L A, Dumler J S, Anderson J F, Johnson R C, Fikrig E. Coexistence of antibodies to tick-borne pathogens of babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, and Lyme borreliosis in human sera. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3054–3057. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.11.3054-3057.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magnarelli L A, Fikrig E, Padula S J, Anderson J F, Flavell R A. Use of recombinant antigens of Borrelia burgdorferi in serologic tests for diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:237–240. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.2.237-240.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magnarelli L A, Flavell R A, Padula S J, Anderson J F, Fikrig E. Serologic diagnosis of canine and equine borreliosis: use of recombinant antigens in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:169–173. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.169-173.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magnarelli L A, IJdo J W, Anderson J F, Padula S J, Flavell R A, Fikrig E. Human exposure to a granulocytic ehrlichia and other tick-borne agents in Connecticut. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2823–2827. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.2823-2827.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magnarelli L A, IJdo J W, Dumler J S, Heimer R, Fikrig E. Reactivity of human sera to different strains of granulocytic ehrlichiae in immunodiagnostic assays. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1835–1838. doi: 10.1086/314516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy C I, Storey J R, Recchia J, Doros-Richert L A, Gingrich-Baker C, Munroe K, Bakken J S, Coughlin R T, Beltz G A. Major antigenic proteins of the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis are encoded by members of a multigene family. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3711–3718. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3711-3718.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pancholi P, Kolbert C P, Mitchell P D, Reed K D, Jr, Dumler J S, Bakken J S, Telford III S R, Persing D H. Ixodes dammini as a potential vector of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:1007–1012. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.4.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petrovec M, Furlan S L, Zupanc T A, Strle F, Brouqui P, Roux V, Dumler J S. Human disease in Europe caused by a granulocytic ehrlichia species. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1556–1559. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1556-1559.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ravyn M D, Goodman J L, Kodner C B, Westad D K, Coleman L A, Engstrom S M, Nelson C M, Johnson R C. Immunodiagnosis of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis by using culture-derived human isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1480–1488. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.6.1480-1488.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Storey J R, Doros-Richert L A, Gingrich-Baker C, Munroe K, Mather T N, Coughlin R T, Beltz G A, Murphy C I. Molecular cloning and sequencing of three granulocytic ehrlichia genes encoding high-molecular-weight immunoreactive proteins. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1356–1363. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1356-1363.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Telford S R, III, Dawson J E, Katavolos P, Warner C K, Kolbert C P, Persing D H. Perpetuation of the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in a deer tick-rodent cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6209–6214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.6209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhi N, Ohashi N, Rikihisa Y, Horowitz H W, Wormser G P, Hechemy K. Cloning and expression of the 44-kilodalton major outer membrane protein gene of the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent and application of the recombinant protein to serodiagnosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1666–1673. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.6.1666-1673.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhi N, Rikihisa Y, Kim H Y, Wormser G P, Horowitz H W. Comparison of major antigenic proteins of six strains of the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent by Western immunoblot analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2606–2611. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2606-2611.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]