Abstract

The nanoparticle has been reported to have severe effects and metabolic disorders in crops. Analysis of poisoning exposure to titanium dioxide is very important during the seed germination stage. Measuring the levels of water supply, reserve mobilization and redox metabolism with germination success is a prerequisite for understanding the TiO2 stress mechanism. These measurements are carried out using different methods, including germination tests, determination of growth parameters, analysis of reserve mobilization processes and redox activities under different stress conditions. The significant effects (P < 0.05) of TiO2 on seed germination were determined by analysis of variance (2 ways-ANOVA). We considered the effect of TiO2 dose (0 and 50 mg/L) and time of exposure (1,2,3,4 and 5 days). The results showed that TiO2 treatment significantly affected the germination rate (GR), the mean daily germination (MDG), the tissues dry weights, water supply, solute leakage, and induced oxidative stress and antioxidant enzyme activities. Oxidative and metabolic disturbances are among the major causes of the successful germination of pea seeds.

Keywords: Germination, Oxidative stress, Pisum sativum L., Seeds, Titanium dioxide

1. Introduction

The incorporation of nanomaterials into diversified products leads to their dissemination in the environment (water, soil, air), as well as the different living species (bacteria, animals, plants…) (He et al., 2015). Crops play a potential role in the food chain. It is therefore an important vehicle of nanoparticles (Missaoui et al., 2021a). The transport of nanoparticles in the environment can be through their penetration and bioaccumulation in plants (Missaoui et al., 2021b). With sizes between 1 and 100 nm, they have some interesting properties (Chemingui et al., 2021a). The term nanoparticles refer to different families such as metal oxides (titanium, copper, zinc, aluminum, silicon), carbon nanotubes, which form solid fibers with special electrical properties, Fullerenes [C60, C70], used to improve the electrical and optical properties of polymers or for pharmaceutical applications, and silver nanopowders, whose antibacterial properties are used in particular in textiles (Chemingui et al., 2021b). Nanoparticles are present in more than a thousand products (Singh et al., 2017). Their small size facilitates their passage through the cells and internal organs (Missaoui et al., 2021a). In addition, nanoparticles have an enormous specific surface area, which increases their ability to interact with living organisms (Chemingui et al., 2019a). Some nanoparticles have the property of adsorbing molecules on their surface that can be toxic (Guey et al., 2020). Plants are the first to be exposed to pollutants, especially nanoparticles (Smiri et al., 2015, Smiri et al., 2016, Missaoui et al., 2017, Chemingui et al., 2019b). The term “Plant nanotoxicology” was introduced as a discipline that studies the effects and mechanisms of nanoparticles in plants, such as transport, surface interactions, and plant-specific responses depending on the nature of the nanoparticle (Dietz and Herth, 2011). Different plants give different responses following exposure to the same nanoparticles (Zhu et al., 2008, Ma et al., 2010). Contaminants must pass through several physical barriers before entering the cytosol of cells. Contamination is highly dependent on climatic conditions, plant species, physiological status, and chemical speciation of the element (Schönherr, 2000, Smiri, 2011, Smiri et al., 2013, Smiri and Missaoui, 2014). In the present work, we analyzed the effect of TiO2 nanoparticles on pea seed germination (germination rate, main daily germination, and germination speed), seedling growth (embryo development), biomass yield (dry matter) concerning oxidative stress (oxidase activities and lipid peroxidation), and antioxidant system (catalase and guaiacol peroxidase activities).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. The plant material

The plant material used is pea (Pisum sativum L. cultivar Merveille de Kelvedon). We looked at the effects of TiO2 using the seedling assay of pea as a model crop. Leguminous plants are among the most important food crops and they are easily cultured and maintained in laboratory conditions. This work aimed to examine the impact of imbibition with TiO2 nanoparticles on seedling growth and the metabolism and behavior of some enzyme capacities involved in oxidative stress.

2.2. Germination condition

seeds are disinfected with sodium hypochlorite (2%) for 10 min, washed thoroughly with distilled water, and then germinated for 5 days in Petri dishes (16 seeds per box) on filter paper moistened with H2O or 50 mg.L−1 TiO2 with size less than 25 nm (Fig. 1). The number of seeds and the volume of imbibition solutions are the same for all treatments. The germination is carried out in the dark in an air-conditioned greenhouse at 25 °C.

Fig. 1.

Germination of pea seeds (Pisum sativum L. cultivar Merveille de Kelvedon) after soaking with H2O or 50 mg.L−1 TiO2.

2.3. Harvest

The germination rate was determined by the interval of 1 day until the maximum germination of the control seeds (H2O) was considered as 100%. At harvest, the germinated seeds are separated into cotyledons and embryonic axes, washed three times with distilled water for 5 min, dried between two sheets of filter paper, and then weighed (Sertorius precision balance to the nearest 0.1 mg). The harvested tissues were (1) dehydrated in an oven at 70 °C for at least 8 days (determination of dry weight) or (2) stored at −80 °C. Germination rate was expressed as the ratio of the number of germinated seeds to the total number of seeds. The number of germinated seeds was determined after 1; 2; 3; 4 and 5 days after the beginning of the experiment. The germination speed was estimated by the average time T50 which corresponds to the germination of 50% of seeds. The main daily germination (MDG) was estimated by the number of seeds germinated over the number of days of imbibition.

2.4. Growth parameters

The embryo axes length was measured every 24 h during the 5 days of treatment. After every 24 h, we determined the weight of the embryo, coat, and cotyledon using a precision balance. We placed tissues at 60 °C for 8 days. These tissues were reweighed to determine the dry weight and water content.

2.5. Reserve mobilization during germination

It is an essential stage of the plant life cycle that allows the growth of the seedling during the early stages of development. The sensitivity of this phase to TiO2 stress is estimated by solute leakage and the effect on translocation (cotyledon-embryo) in the different seed tissues. Electrolyte leakage measurements were assayed with a conductivity meter (Model 250, Denver Instrument). The electrical conductivity was expressed based on seed number (Missaoui et al., 2019). Blanks containing water.

2.6. Enzyme assays

Embryonic axes were ground in a mortar with pestle in a medium (w/v = 1/5) containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.4 M sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM ascorbic acid and 1 mM MgCl2. The homogenate was squeezed through double cheesecloth and centrifuged at 5000g for 20 min. The supernatant obtained was carefully decanted and used for GPOX, CAT, and NADH oxidase assays. Enzyme activities (GPOX, CAT, and NADH oxidase) were expressed as units per gram of fresh weight (U g − 1 FW) and were detected using an Ultraviolet–Visible spectrophotometer (Lamba 2, PerkinElmer). Lipid peroxidation was estimated by determining the concentration of MDA (Hernández and Almansa, 2002). Fresh samples (250 mg) were homogenized in 2 mL of 0.1% trichloroacetic acid (TCA). The homogenate was squeezed through double cheesecloth and centrifuged at 3000g for 15 min.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Germination data were arcsine transformed before statistical analysis to ensure homogeneity of variance. The significant effects (P < 0.05) of TiO2 on seed germination were determined by analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SPSS version 23 for Windows. If the ANOVA indicated a significant effect, then post hoc Bonferroni tests were performed to compare treatment means.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of TiO2 on germination rate

The results presented in Table 1 showed that the germination process was vulnerable to TiO2 enrichment of the imbibition medium. The germination rate of TiO2-soaked seeds decreased by 16% compared to controls after 5 days of seed imbibition. Main daily germination (MDG) and germination speed (T50) of P. sativum in response to variable TiO2 (0–50 mg/L TiO2) were determined. At 0 mg/L TiO2, MDG was about 1.90 seed/day and T50 was obtained after 2 days. After treatment with 50 mg/L TiO2, we showed a regression in MDG (1.60 seed/day) and T50 were obtained after 2 days. The effects of TiO2 on seed germination success vary significantly depending on the dose and the treatment time (Table 2).

Table 1.

Seed germination rate, main daily germination (MDG), and germination speed (T50) of (Pisum sativum L. cultivar Merveille de Kelvedon) in response to variable titanium dioxide (0–50 mM TiO2). Different letters via the Bonferroni test indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) between treatments.

| Treatments | Germination rate | MDG | T50 |

|---|---|---|---|

| TiO2 (0 mg/L) | 95a | 1.90 | 2 |

| TiO2 (50 mg/L) | 80b | 1.60 | 2 |

Table 2.

Results of two-way ANOVA of characteristics by variable doses of titanium dioxide (D) and Time (T) and their interactions on the rate of seed germination of Pisum sativum L. cultivar Merveille de Kelvedon in 12 h photoperiod condition.

| Independent variables | D | T | D × T | Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| df | 2 | 5 | 10 | |

| Pisum sativum L. | 18.74*** | 40.65*** | 31.10*** | MS :3.00 |

Superscript *** denotes significant difference at P < 0.05, Data represent F values.

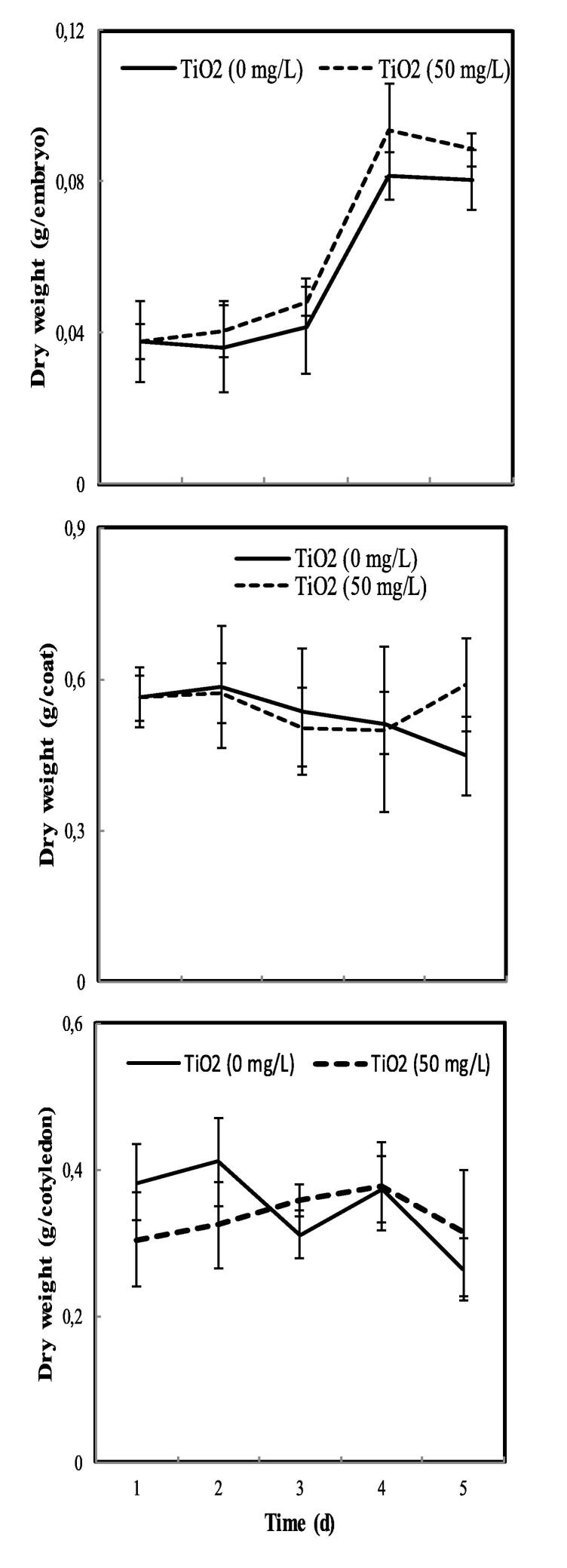

3.2. Effect of TiO2 on pea embryo growth

Treatment of pea seeds with TiO2 induces embryonic axis biomass by 10% after 5 days of germination compared to the control (Fig. 2). There are no significant effects of TiO2 on the dry biomass of the seed coat and the cotyledons.

Fig. 2.

The dry weight of the embryo, coat, and cotyledon of pea seeds during germination after soaking with H2O or 50 mg.L−1 TiO2. The values represent the mean of two independent experiments. Each experiment is performed with 16 seeds. Superscript * denotes significant difference at P < 0.05.

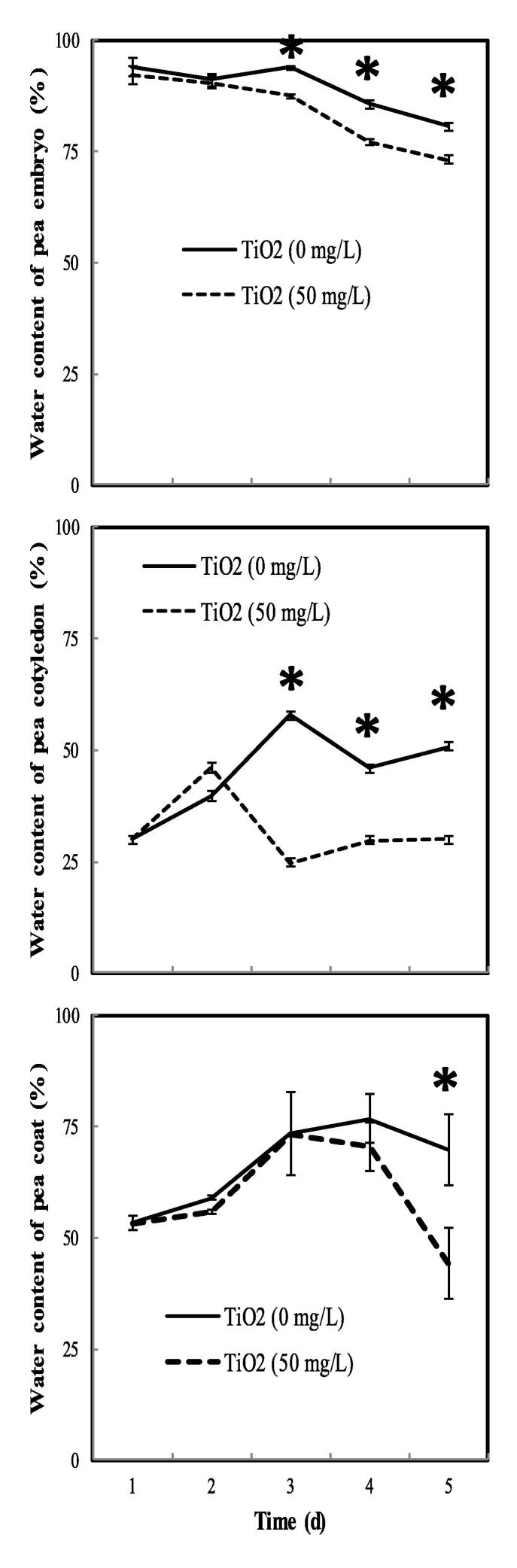

3.3. Water absorption in pea embryo

The results presented in Fig. 3 show a blockage of water absorption and dehydration of pea tissues after treatment with TiO2. A 10%, 36%, and 43% of decrease in water content in the embryonic axes, coat, and cotyledon, respectively, after 5 days of germination of treated pea seeds compared to controls.

Fig. 3.

The water content of the embryo, coat, and cotyledon of pea seeds during germination after soaking with H2O or 50 mg.L−1 TiO2. The values represent the mean of two independent experiments. Each experiment is performed with 16 seeds. Superscript * denotes significant difference at P < 0.05.

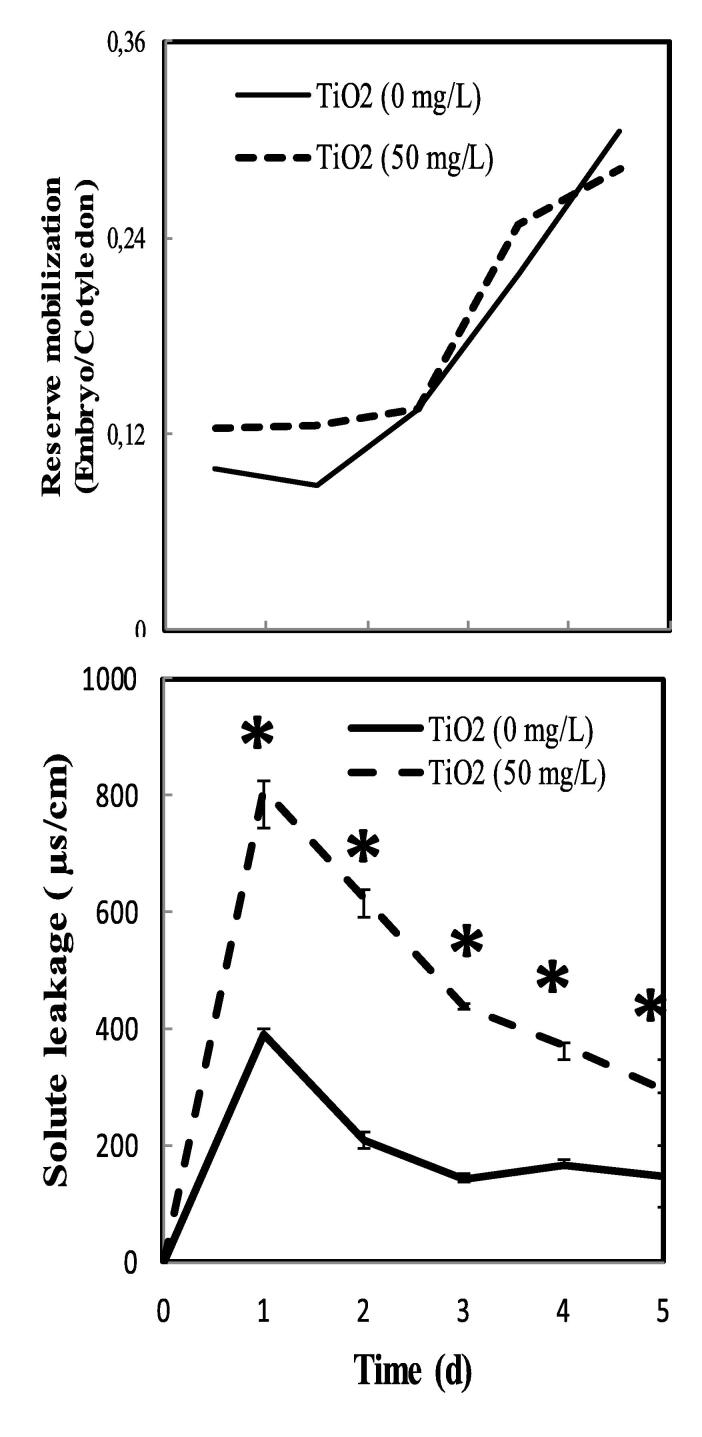

3.4. Reserve mobilization

TiO2 treatments do not affect the translocation between axes and cotyledons of pea seeds (Fig. 4A). The curve corresponding to the variation in biomass of the embryonic axes compared to the cotyledons of seeds treated with TiO2 follows the curve of the control seeds. We recorded a strong leakage of solute in the imbibing medium after treatment with 50 mg/L of TiO2. The highest leakage was observed after 24 h (Fig. 4B). It exceeds twice times that of control.

Fig. 4.

Variation in the report of the biomass of the embryonic axes compared to that of the cotyledons and solute leakage of pea seeds during germination after soaking with H2O or 50 mg.L−1 TiO2. Superscript * denotes significant difference at P < 0.05.

3.5. Oxidative stress in pea embryo

We used two stress biomarkers to demonstrate the possible installation of oxidative stress in pea embryos due to imbibition with water enriched with TiO2: malonaldehyde as a lipid peroxidation marker, and NADH oxidase as membrane-bound proteins transferred electrons across the plasma membrane to molecular oxygen. The results obtained in Fig. 5A show stimulation of lipid peroxidation from the first 48 h of more than 62% in pea embryo of seed imbibed with TiO2 compared with control. Similarly, TiO2 stimulates NADH oxidase activity in pea embryos by about 162% after three days of treatment Fig. 5A.

Fig. 5.

NADH oxidase (A) and MDA (B) activities in embryos of pea seeds during germination after imbibition with H2O or 50 mg.L−1 TiO2. Data are means (±SE) of five replicates. Superscript * denotes significant difference at P < 0.05.

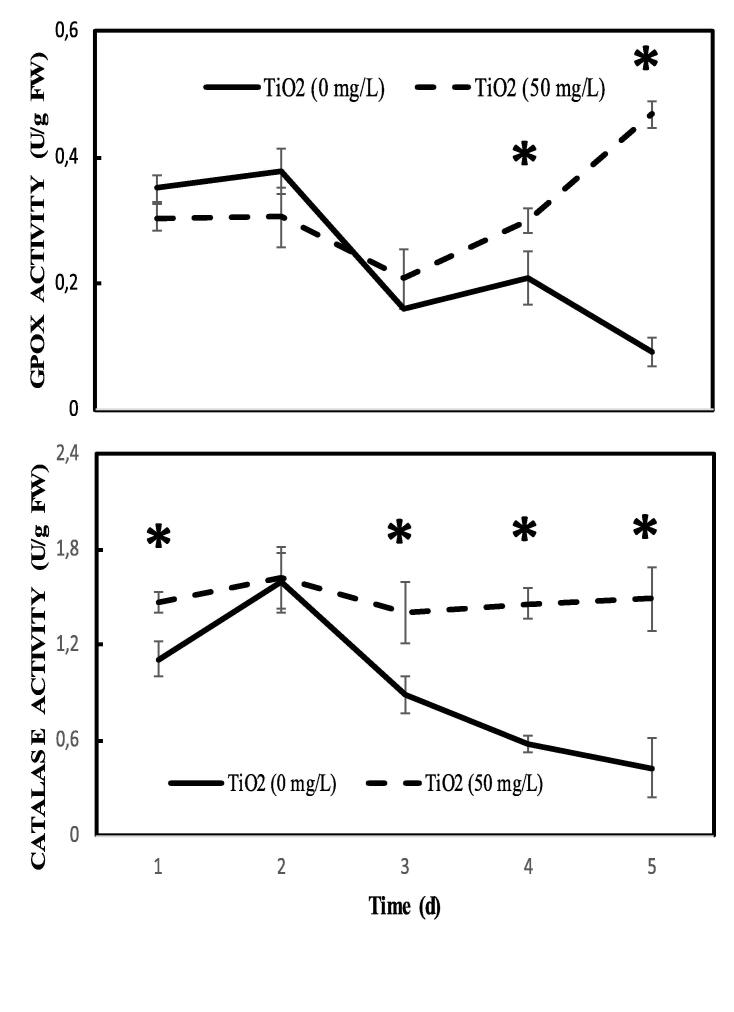

3.6. Antioxidant system in pea embryo

The antioxidant activity involves non-enzymatic elements such as glutathione, but especially antioxidant enzymes. We monitored the guaiacol peroxidase and catalase activities. TiO2 stimulates more than 4 and 3 times the GPOX and catalase activities, respectively, after 5 days of treatment (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Guaiacol peroxidase (A) and catalase (B) activities in embryos of pea seeds during germination after imbibition with H2O or 50 mg.L−1 TiO2. Data are means (±SE) of five replicates. Superscript * denotes significant difference at P < 0.05.

4. Discussion

Nanoparticles are more and more widespread on earth. The use of nanoparticles is diversified. The study of the toxicity of nanoparticles in plants varies depending on the type of nanoparticle (Missaoui et al., 2017), dose (Missaoui et al., 2021b), time of exposure (Chemingui et al., 2019b), and manner of exposure (Missaoui et al., 2021a). Little is known about the mechanisms of nanoparticle toxicity. The toxicity of TiO2 could be explained by disturbances of growth actors during the seedling stage, which leads to a delay in the level of weight as well as in the level of embryo length. Nanoparticles involved plant growth, development, and protection due to interaction with nutrient supply, pathogenicity, photosynthetic capacity, and germination success (Agrahari and Dubey, 2020). The positive and/or negative impacts of nanoparticles can be established. With 50 mg/L TiO2, we showed a delay in pea seed germination, embryo development, and water supply (Figs. 2 and 3). Raskar and Laware (2013) point out the possible use of TiO2 NPs in onion to promote seed germination and early seedling growth at low concentrations (10–50 μg mL-1). Mean germination time was affected at 10 ppm concentration of TiO2 in wheat (Feizi et al., 2011). TiO2 with four concentrations (0, 10, 30, 60 μg/ml) increased calli size and embryogenesis of barley mature embryos were cultured in Murashige and Skoog medium (Mandeh et al., 2012). In agreement with our results, relative water content was significantly enhanced during nano-priming treatment with 60 ppm of TiO2 in maize seedling (Shah et al., 2020). The blockage of water absorption at the embryonic axes could explain, at least in part, the delay in growth as well as the success of pea seed germination treated with TiO2. A second fundamental event in seed germination is that of reserve mobilization. This event is very affected by TiO2 (Fig. 4). The strong solute leakage proved a disorder in the mechanisms of transport of solutes from the pea cotyledons to the embryonic axes. Nano-TiO2 (500 mg/L) decreased the membrane electrolyte leakage in barley germination seeds under salinity stress (Karami and Sepehri, 2018). In previous work with cobalt nanoparticles, the content of electrolyte leakage increased after 250 mg L−1 of Co3O4 NPs and showed a maximum level of 4000 mg L−1 (Jahani et al., 2020). The variation in the solute leakage of pea seeds during germination after soaking with 50 mg.L−1 TiO2 can be attributed to a disorder in nutrient supply. Another explanation of high solute leakage is that attributed to oxidative stress, especially lipid peroxidation (Fig. 5). TiO2 induced lipid peroxidation and oxidase activities. NP treatments triggered the accumulation of reactive oxygen species, increased production of stress enzymes, lipid peroxidation that mediated oxidative stress in lentils (Khan et al., 2019). Ebrahimi et al. (2016) showed the installation of oxidative stress in Phaseolus vulgaris seedlings and disorder in antioxidant systems after treatment with TiO2 NPs. In the same way, we showed that TiO2 induced the antioxidant enzyme activities guaiacol peroxidase and catalase (Fig. 6). Despite the stimulation of the antioxidant system in the pea stressed by TiO2, it appears that there is a significant lipid peroxidation activity that disrupted the processes of transport in the membrane of water and solutes. These oxidative and metabolic disturbances are among the major causes of successful germination.

5. Conclusion

Drastic reduction of biomass production and nutritional quality have been often observed in crops grown in a contaminated environment. Seed germination is an important stage of plant life, which is highly sensitive to surrounding medium changes since the germinating seed is the first interface of material exchange between the plant cycle and the environment. This work aimed to examine the impact of imbibition with TiO2 nanoparticles on seedling growth and the metabolism and behavior of some enzyme capacities involved in oxidative stress. We have tried with a dose of 50 mg.L−1 TiO2 and for different treatment durations to highlight the mechanism of toxicity of this pollutant on the different tissues of the pea seeds. The results showed that TiO2 treatment significantly affected the germination rate (GR), the mean daily germination (MDG), the tissues dry weights, water supply, solute leakage, and induced oxidative stress and antioxidant enzyme activities. There is a significant lipid peroxidation activity that disrupted the processes of transport of water and solutes. Oxidative and metabolic disturbances are among the major causes of the successful germination of pea seeds.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Dr. Moêz Smiri for help on plant material selection and discussion.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Agrahari S., Dubey A. In: Biogenic Nano-Particles and their Use in Agro-ecosystems. Ghorbanpour M., Bhargava P., Varma A., Choudhary D., editors. Springer; Singapore: 2020. Nanoparticles in Plant Growth and Development. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chemingui H., Rezma S., Lafi R., Alhalili Z., Missaoui T., Harbi I., Smiri M., Hafiane A. Investigation of methylene blue adsorption from aqueous solution onto ZnO nanoparticles: equilibrium and Box-Behnken optimisation design. Inter. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2021 doi: 10.1080/03067319.2021.1897121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chemingui H., Smiri M., Missaoui T., Hafiane A. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Induced Oxidative Stress and Changes in the Photosynthetic Apparatus in Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum graecum L.) Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2019;102:477–485. doi: 10.1007/s00128-019-02590-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemingui H., Missaoui T., Mzali J.C., Moez Smiri, Hafiane A., Yatmaz H.C. Facile green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs): Antibacterial and photocatalytic activities. Mater. Res. Exp. 2019;6(10):1050B4. doi: 10.1088/2053-1591/ab3cd6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chemingui H., Mzali J.C., Missaoui T., Konyar M., Smiri M., Yatmaz H.C., Hafiane A. Characteristic of Er-doped zinc oxide layer: application to color removal of synthetic dye solution. Desal. Water Treat. 2021;402–413 doi: 10.5004/dwt.2021.26644. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz K.J., Herth S. Plant nanotoxicology. Trends Plant Sci. 2011;16(11):582–589. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimi A., Galavi M., Ramroudi M., Moaveni P. Effect of TiO2 Nanoparticles on Antioxidant Enzymes Activity and Biochemical Biomarkers in Pinto Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) J. Mol Biol. Res. 2016;6(1):58. doi: 10.5539/jmbr.v6n1p58. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feizi H., Rezvani Moghaddam P., Shahtahmassebi N., Fotovat A. Impact of Bulk and Nanosized Titanium Dioxide (TiO2) on Wheat Seed Germination and Seedling Growth. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2011;146(1):101–106. doi: 10.1007/s12011-011-9222-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guey F., Smiri M., Chemingui H., Dekhil A.B., Elarbaoui S., Hafiane A. Remove of Humic Acid From Water Using Magnetite Nanoparticles. European J. Adv. Chem. Res. 2020;1(4):9. doi: 10.24018/ejchem. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Aker W.G., Fu P.P., Hwang H.-M. Toxicity of engineered metal oxide nanomaterials mediated by nano–bio–eco–interactions: a review and perspective. Environ. Sci. Nano. 2015 doi: 10.1039/c5en00094g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez J.A., Almansa M.S. Short-term effects of salt stress on antioxidant systems and leaf water relations of pea leaves. Physiologia Plantarum. 2002;115(2):251–257. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2002.1150211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahani M., Khavari-Nejad R.A., Mahmoodzadeh H., Saadatmand S. Effects of cobalt oxide nanoparticles (Co3O4 NPs) on ion leakage, total phenol, antioxidant enzymes activities and cobalt accumulation in Brassica napus L. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca. 2020;48(3):1260–1275. doi: 10.15835/nbha48311766. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karami A., Sepehri A. Effect of Nano Titanium Dioxide and Sodium nitroprusside on seed germination, vigor index and antioxidant enzymes of Afzal barley seedling under salinity stress. Iranian J. Seed Sci. Res. 2018;5(3):47–61. [Google Scholar]

- Khan Z., Shahwar D., Yunus Ansari M.K., Chandel R. Toxicity assessment of anatase (TiO2) nanoparticles: A pilot study on stress response alterations and DNA damage studies in Lens culinaris Medik. Heliyon. 2019;5(7) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X., Geiser-Lee J., Deng Y., Kolmakov A. Interactions between engineered nanoparticles (ENPs) and plants: Phytotoxicity, uptake, and accumulation. Sci. Total Environ. 2010;408:3053–3061. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandeh M., Omidi M., Rahaie M. In Vitro Influences of TiO2 Nanoparticles on Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Tissue Culture. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2012;150(1–3):376–380. doi: 10.1007/s12011-012-9480-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missaoui T., Smiri M., Chemingui H., Hafiane A. Effects of nanosized titanium dioxide on the photosynthetic metabolism of fenugreek (Trigonella foenum graecum L.) C. R. Biol. 2017;340(11–12):499–511. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2017.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missaoui T., Smiri M., Hafiane A. Reserve Mobilization, Membrane Damage and Solutes Leakage in Fenugreek Imbibed with Urban Treated Wastewater. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s00128-019-02658-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missaoui T., Smiri M., Chemingui H. Effect of Nanosized TiO2 on Redox Properties in Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum graecum L.) during Germination. Environ. Process. 2021;8:843–867. doi: 10.1007/s40710-020-00493-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Missaoui T., Smiri M., Chemingui H., Alhalili Z., Hafiane A. Disturbance in Mineral Nutrition of Fenugreek Grown in Water Polluted with Nanosized Titanium Dioxide. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2021;106(4):557. doi: 10.1007/s00128-020-03051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskar S., Laware S.L. Effect of titanium dioxide nano particles on seed germination and germination indices in onion. Plant Sci. Feed. 2013;3(9):103–107. [Google Scholar]

- Schönherr J. Calcium chloride penetrates plant cuticles via aqueous pores. Planta. 2000;212:112–118. doi: 10.1007/s004250000373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah T., Latif S., Saeed F., Ali I., Ullah S., Abdullah Alsahli A., Ahmad P. Seed priming with titanium dioxide nanoparticles enhances seed vigor, leaf water status, and antioxidant enzyme activities in maize (Zea mays L.) under salinity stress. J. King Saud University-Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jksus.2020.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S., Tripathi D.K., Dubey N.K., Chauhan D.K. Effects of nano-materials on seed germination and seedling growth: striking the slight balance between the concepts and controversies. Mater. Focus. 2017;5:195–201. doi: 10.1166/mat.2016.1329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smiri M. Effect of cadmium on germination, growth, redox and oxidative properties in Pisum sativum seeds. J. Environ. Chem. Ecotox. 2011;3(3):52–59. doi: 10.5897/JECE.9000017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smiri M., Jelali N., El Ghoul J. Cadmium affects the NADP-thioredoxin reductase/thioredoxin system in germinating pea seeds. J. Plant Inter. 2013;8(2):125–133. doi: 10.1080/17429145.2012.689865. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smiri M., Missaoui T. The role of ferredoxin: thioredoxin reductase/ thioredoxin m in seed germination and the connection between this system and copper ion toxicity. J. Plant Physiol. 2014;171:1664–1670. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2014.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smiri M., Elarbaoui S., Missaoui T., Ben Dekhil A. Micropollutants in Sewage Sludge: Elemental Composition and Heavy Metals Uptake by Phaseolus vulgaris and Vicia faba Seedlings. Arabian J. Sci. Eng. 2015;40:1837–1847. doi: 10.1007/s13369-015-1639-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smiri M., Bousami S., Missaoui T., Hafiane A. In: Redox State as a Central Regulator of Plant-Cell Stress Responses. Gupta D.K., Palma J.M., Corpas F.J., editors. Springer International Publishing; Switzerland: 2016. The cadmium-binding thioredoxin o acts as an upstream regulator of the redox plant homeostasis; p. 350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H., Han J., Xiao J.Q., Jin Y. Uptake, translocation, and accumulation of manufactured iron oxide nanoparticles by pumpkin plants. J. Environ. Monitor. 2008;10:713–717. doi: 10.1039/b805998e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]