Abstract

Widowhood is a catastrophic event at any stage of life for the surviving partner particularly in old age, with serious repercussions on their physical, economic, and emotional well-being. This study investigates the association of marital status and living arrangement with depression among older adults. Additionally, the study aims to evaluate the effects of factors such as socio-economic conditions and other health problems contributing to the risk of depression among older adults in India. This study utilizes data from the nationally representative Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI-2017–18). The effective sample size was 30,639 older adults aged 60 years and above. Descriptive statistics and bivariate analysis have been performed to determine the prevalence of depression. Further, binary logistic regression analysis was conducted to study the association between marital status and living arrangement on depression among older adults in India. Overall, around nine percent of the older adults suffered from depression. 10.3% of the widowed (currently married: 7.8%) and 13.6% of the older adults who were living alone suffered from depression. Further, 8.4% of the respondents who were co-residing with someone were suffering from depression. Widowed older adults were 34% more likely to be depressed than currently married counterparts [AOR: 1.34, CI 1.2–1.49]. Similarly, respondents who lived alone were 16% more likely to be depressed compared to their counterparts [AOR: 1.16; CI 1.02, 1.40]. Older adults who were widowed and living alone were 56% more likely to suffer from depression [AOR: 1.56; CI 1.28, 1.91] in reference to older adults who were currently married and co-residing. The study shows vulnerability of widowed older adults who are living alone and among those who had lack of socio-economic resources and face poor health status. The study can be used to target outreach programs and service delivery for the older adults who are living alone or widowed and suffering from depression.

Subject terms: Geriatrics, Public health

Introduction

The pace of world population aging has been the fastest in recent years. According to Help Age India, the people aged 60 and above are classified as older population in India, whose proportion is projected to rise to 19.5 percent by 20501. However, the significance of the rapid increase in life expectancy and its implication is yet to be appreciated as increased life expectancy does not mean the improved quality of life among older adults2. Most countries, including developing countries with a constant increase in longevity, pose serious challenges such as increased risks of multi-morbidity, disability, dementia and, weakening their functional capability, and increasing dependence for personal, household, and medical care3,4.

The average life span in the world is expected to double in the twentieth century5. With increased longevity in some countries, the concept of widowhood has broadened due to growing concerns of older adults whose spouse has died, and their likelihood of living alone for a longer period has also increased6. Approximately 350 million people are estimated to be widowed in 2020, out of which about 80 percent are females7. Some predominant reasons for increased risk for women to outlive men are related to the higher life expectancy of females due to their biological advantages over men. However, the differences in life expectancy between the two sexes are not purely biological and there are intervening social factors such as the age gap in marriage, higher risk-taking behavior, and increased substance use among men8.

Widowhood is an irreversible situation9. It is a catastrophic event at any stage of life for the surviving partner with serious repercussions on their physical, economic, and emotional well-being, particularly in the first year of the loss or for a longer term in some cases10. However, the emotional response to the spousal loss is hypothesized to be different depending on various socio-demographic characteristics such as age, gender, widowhood duration, living arrangement, functional ability to perform activities, health status and other factors such as community involvement and economic conditions of the survivor11–13. Widowhood often places individuals at a greater risk of deteriorating health and depressive symptoms with passing time post spousal loss for both sexes7. Across studies, prevalence rates of depressive symptoms are estimated to be high as 15–30 percent within the first year of widowhood10. However, it remains unclear whether widowhood has more psychological consequences on males or females. Differences between the two sexes in depression due to spousal loss is argued to differ according to gender roles; as compared to men, women are found to invest less in their financial security and more in familial relationships. After the bereavement of the spouse, their only source of income is lost, which increases their economic hardships at older ages leading to an adverse impact on their psychological well-being7,14,15. Few studies suggest that men and women have similar difficulty adapting to widowhood and reorganizing their lives after the spousal loss6. However, the loss of a spouse is not always associated with negative outcomes. For instance, some studies observed improvement of well-being and lower depressive symptoms among older widows after spousal bereavement, due to reorientation of life, and increased time for individual development because of the decreased burden of caregiving16. Considering the large variation in reaction to spousal loss, this as a generalized hypothesis as an outcome of widowhood is not appropriate. In many countries like India where widows account for a larger proportion of the population, widowhood is considered as the most dreaded phase of life due to strict gender roles, stigma and prevailing traditional customs along with poverty, abuse and lack of social support17. Widowhood brings serious economic challenges, and studies have found wealth status to be a strong predictor of health outcomes among older adults17–19. However, it is unclear whether economic status after a spouse's death is a primary cause for the psychological distress among older adults.

Marital status and its link with mental health has been explored previously, concluding that unmarried and widowed individuals show higher rates of loneliness, lower life satisfaction, physical ailments, and higher mortality20. Globally, about 90 million older adults are estimated to live alone, of which roughly about 60 million are females; still, a great majority of older adults have only been in one union and decide not to marry after the spousal bereavement in older age21. Troubled mental state during this phase, such as negative emotions and feelings of emptiness, are challenging for many older adults; as a result, they may tend to withdraw and become unresponsive22. However, remarriage in older age is still an exception. Widowed men are observed to remarry at a rate twice as high than female widows23. Co-residence with family and community involvement is more common for widows24,25. Previous studies have explicitly discussed depression and other psychological illnesses such as dementia in association with population aging, and a few have also reflected on the role of spousal loss in old age26,27. The effect of widowhood and co-residence with family together on depression has been observed, but is rather inconclusive; and some studies also suggest that older widowed women who are sick and more depressed might be more likely to co-reside with family28.

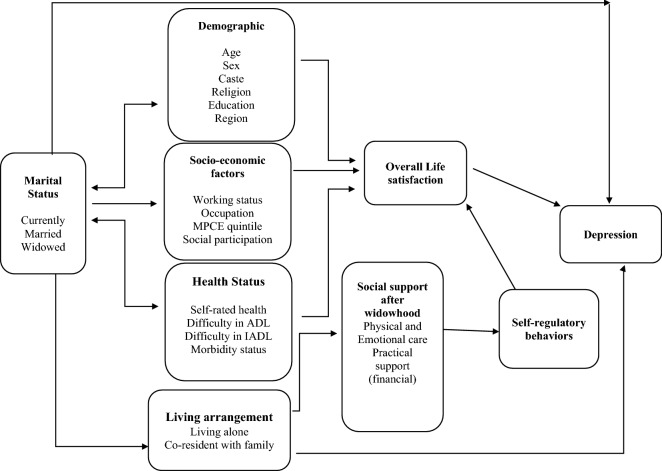

Therefore, the present study attempts to address the literature gap by providing empirical evidence, and to examine the association between marital status and living arrangements with depression among older adults in India. Figure 1 represents the conceptual framework for the present study. Additionally, the study also aims to examine the factors that contribute to the risk of depression among older adults. The study hypothesizes that there is a strong association between widowhood and living alone on depression among older adults.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework.

Methods

Data

This study utilizes data from India’s first nationally representative Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI-2017–18), which investigates the health, economics, and social determinants and consequences of population aging in India29. The representative sample included 72,250 individuals aged 45 and above and their spouses across all states and union territories of India except Sikkim. The LASI includes 31,464 older adults aged 60 years and above and 6749 oldest-old persons aged 75 years and above. The LASI adopts a multistage stratified area probability cluster sampling design to select the eventual units of observation. Households with at least one member aged 45 and above were taken as the eventual unit of observation. The response rate was 95.6% for the individual interviews and 92.7% in household interviews. The LASI survey provides information on demographics, household economic status, chronic health conditions, symptom-based health conditions, functional and mental health, biomarkers, health care utilization, work, and employment, etc. It enables the cross-state analyses of aging, health, economic status, and social behaviors and has been designed to evaluate the effect of changing policies and behavioral outcomes in India. Detailed information on the sampling frame is available on the LASI WAVE-1 Report.

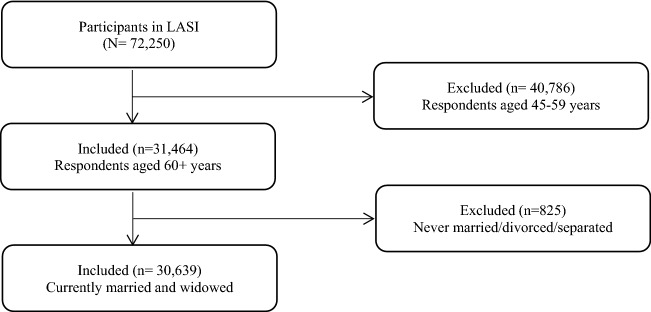

Selection of the study sample

The effective sample size for the present study was 30,639 older adults. There were no missing values and hence the whole sample was taken into consideration for the analysis. Older adults who were never married/divorced/separated (825 older adults) were dropped from the sample (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Sample selection criteria.

Variable description

Outcome variable

The outcome variable for the study was depression which was coded as 0 for “not diagnosed with depression” and 1 for “diagnosed with depression”. Major depression among the older adults with symptoms of dysphoria, calculated using the CIDI-SF (Short Form Composite International Diagnostic Interview) score of 3 or more on a scale of 0 to 10. The score of less than 3 was categorized as “not diagnosed with depression” and score of 3 and more was categorized as “diagnosed with depression”. This scale estimates a probable psychiatric diagnosis of major depression and has been validated in field settings and widely used in population-based health surveys29. The scale was validated for older adults30. The questions used to assess depression are presented in appendix.

Exposure variables

Main exposure variables

Marital status was categorized as currently married and widowed. Living arrangement was categorized as co-residing, which includes living with a spouse, with children, or living with others; and living alone.

Other exposure variables

Age was categorized as young old (60–69 years), old-old (70–79 years), and oldest-old (80 + years). Sex was categorized as male and female. Educational status was categorized as no education/primary not completed, primary, secondary and higher. Working status was categorized as currently working, retired, and not working19. Social participation was categorized as no and yes. Social participation was measured through the question, “Are you a member of any of the organizations, religious groups, clubs, or societies”? The response was categorized as no and yes. Life satisfaction among older adults was assessed using the questions a. In most ways, my life is close to ideal; b. The conditions of my life are excellent; c. I am satisfied with my life d. So far, I have got the important things I want in life; e. If I could live my life again, I would change almost nothing. The responses were categorized as strongly disagree, somewhat disagree, slightly disagree, neither agree nor disagree, slightly agree, somewhat agree, and strongly agree. Using the responses to the five statements regarding life satisfaction, a scale was constructed. The categories of the scale are ‘low satisfaction (score of 5–20), ‘medium satisfaction’ (score of 21–25), and ‘high satisfaction’ (score of 26–35). Self-rated health was coded as good which includes excellent, very good, and good, whereas poor, includes fair and poor.

Difficulty in ADL (Activities of Daily Living) was coded as no and yes31. Activities of Daily Living (ADL) is a term used to refer to normal daily self-care activities (such as movement in bed, changing position from sitting to standing, feeding, bathing, dressing, grooming, personal hygiene, etc.) The ability or inability to perform ADLs is used to measure a person’s functional status, especially in the case of people with disabilities and the elderly. Difficulty in IADL (Instrumental Activities of Daily Living) was coded as no and yes31. Activities of daily living that are not necessarily related to the fundamental functioning of a person, but they let an individual live independently in a community. These tasks are necessary for the independent functioning of older adults in the community. Morbidity status was categorized as 0 “no morbidity”, 1 “any single morbid condition”, and 2 + “co-morbidity”. Morbidity was assessed by self-report where the interviewer asked the participant whether any health professional ever diagnosed them with the following diseases? The diseases were a. Hypertension or high blood pressure b. Diabetes or high blood sugar c. Cancer or a malignant tumour d. Chronic lung disease such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/Chronic bronchitis or other chronic lung problems, e. Chronic heart diseases such as Coronary heart disease (heart attack or Myocardial Infarction), congestive heart failure, or other chronic heart problems f. Stroke g. Arthritis or rheumatism, Osteoporosis or other bone/joint diseases h. Any neurological or psychiatric problems i. High cholesterol. All the morbidities were self-reported32.

The monthly per capita consumption expenditure (MPCE) quintile was assessed using household consumption data. Sets of 11 and 29 questions on the expenditures on food and non-food items, respectively, were used to canvas the sample households. The variable was then divided into five quintiles, i.e., from poorest to richest. Religion was coded as Hindu, Muslim, Christian, and Others. Caste was recoded as Scheduled Tribe (ST), Scheduled Caste (SC), Other Backward Class (OBC), and others. The ST includes a group of the population that is socially segregated and have a financially/economically low status as per Hindu caste hierarchy. The SC and ST are among the most disadvantaged socio-economic groups in India. The OBC is the group of people who were identified as “educationally, economically and socially backward”. The OBC is considered low in the traditional caste hierarchy but somewhere above the boundary of the most disadvantaged groups. The “other” caste category is identified as having higher social status33,34. Place of residence was categorized as rural and urban. The region was coded as North, Central, East, Northeast, West, and South.

Statistical analysis

In this study, descriptive statistics and bivariate analysis has been performed to determine the prevalence of depression by socio-economic status and other factors in the country. A Chi-square test was used to check the significance level for the bivariate association. Further, binary logistic regression analysis35 was conducted to study the association between marital status and living arrangements with depression among older adults. The results are presented in the form of an odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. In model-3, interaction effects were observed for marital status and living arrangement with depression among older adults in India. Model-1 was an unadjusted model whereas Model-2 provided the adjusted estimates. Model-3 provides the interaction estimates which are adjusted for all other covariates. In model-3 the interaction effects (Marital status # Living arrangement) were observed therefore the independent effect of marital status and living arrangement were estimated. Model-1 was controlled for marital status and living arrangement; Model-2 and 3 was controlled for marital status, living arrangement, age, sex, education, working status, social participation life satisfaction, self-rated health, difficulty in ADL, difficulty in IADL, morbidity status MPCE quintile, religion, caste, place of residence, region.

The regression diagnostics for heteroscedasticity36, multicollinearity37, and outliers were performed via computation of variance inflation factors (VIFs) and visual inspection of residual plots for the regression models. The cut-off of 10 or more was considered unacceptable; i.e., if the score was 10 or more, then the variables are expected to have multicollinearity between them. The complex survey design effects were adjusted by using STATA svyset and svy commands. The whole statistical analyses were performed by using STATA version 1438.

Results

Background characteristics of the eligible respondents are presented in Table 1. Analysis indicated that around sixty-three percent of the older adults in India were currently married. A majority of the older Indian adults (94%) were co-residing with their families. As far as education is concerned, the majority of the older adults in the country were uneducated or had not completed primary education (68%), and one-fourth of them had primary or secondary level of education, and only seven percent of them had the higher education.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic profile of older adults in India.

| Background characteristic | Sample | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Marital status | ||

| Currently married | 19,302 | 63.0 |

| Widowed | 11,337 | 37.0 |

| Living arrangement | ||

| Co-residing | 28,990 | 94.6 |

| Living alone | 1,649 | 5.4 |

| Age | ||

| Young-old | 17,902 | 58.4 |

| Old-old | 9,287 | 30.3 |

| Oldest-old | 3,450 | 11.3 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 14,502 | 47.3 |

| Female | 16,137 | 52.7 |

| Education | ||

| No education/primary not completed | 20,815 | 67.9 |

| Primary completed | 3,421 | 11.2 |

| Secondary completed | 4,258 | 13.9 |

| Higher and above | 2,144 | 7.0 |

| Working status | ||

| Working | 9,387 | 30.6 |

| Retired | 13,127 | 42.8 |

| Not working | 8,126 | 26.5 |

| Social participation | ||

| No | 29,263 | 95.5 |

| Yes | 1,376 | 4.5 |

| Life satisfaction* | ||

| Low | 9,444 | 31.9 |

| Medium | 6,615 | 22.3 |

| High | 13,548 | 45.8 |

| Self-rated health* | ||

| Good | 15,451 | 51.5 |

| Poor | 14,567 | 48.5 |

| Difficulty in ADL* | ||

| No | 23,263 | 76.2 |

| Yes | 7,253 | 23.8 |

| Difficulty in IADL* | ||

| No | 15,793 | 51.8 |

| Yes | 14,723 | 48.3 |

| Morbidity status | ||

| 0 | 14,333 | 46.8 |

| 1 | 8,949 | 29.2 |

| 2 + | 7,357 | 24.0 |

| MPCE quintile | ||

| Poorest | 6,614 | 21.6 |

| Poorer | 6,660 | 21.7 |

| Middle | 6,421 | 21.0 |

| Richer | 5,906 | 19.3 |

| Richest | 5,038 | 16.4 |

| Religion | ||

| Hindu | 25,181 | 82.2 |

| Muslim | 3,480 | 11.4 |

| Christian | 861 | 2.8 |

| Others | 1,116 | 3.6 |

| Caste | ||

| Scheduled Caste | 5,827 | 19.0 |

| Scheduled Tribe | 2,496 | 8.2 |

| Other Backward Class | 13,783 | 45.0 |

| Others | 8,534 | 27.9 |

| Place of residence | ||

| Rural | 21,639 | 70.6 |

| Urban | 9,000 | 29.4 |

| Region | ||

| North | 3,887 | 12.7 |

| Central | 6,440 | 21.0 |

| East | 7,316 | 23.9 |

| Northeast | 912 | 3.0 |

| West | 5,275 | 17.2 |

| South | 6,809 | 22.2 |

| Total | 30,639 | 100.0 |

*The sample may differ due to missing cases; ADL: Activities of Daily Living; IADL: Instrumental Activities of Daily Living.

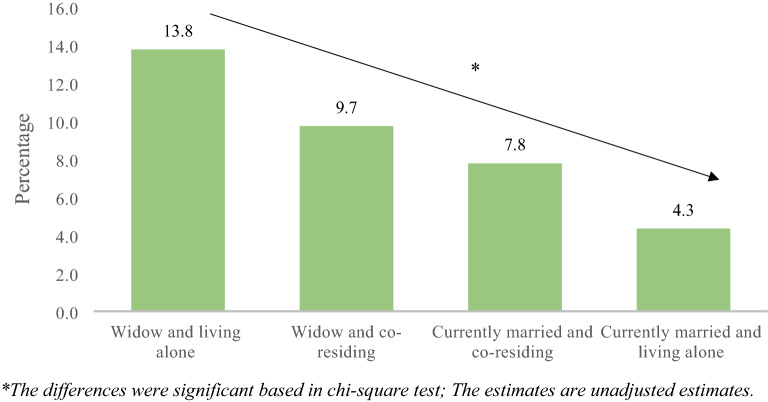

Figure 3 represents the percentage of older adults suffering from depression by their marital status and living arrangement. It was revealed that about 13.8% of older adults who were widowed and living alone suffered from depression in reference to an older adult who was a widow but co-reside (9.7%), currently married, and co-residing (7.8%), and currently married living alone (4.3%). The differences were significant based on the chi-square test.

Figure 3.

Percentage of older adults suffering from depression by their marital status and living arrangement.

Table 2 presents the proportion of older adults suffering from depression by background characteristics in the country. Overall, around nine percent of the older adults in the country were suffering from depression. As evident from the data, about 10.3% of the widowed older adults were suffering from depression (currently married: 7.8%). Nearly 13.6% of the older adults who were living alone were suffering from depression whereas around 8.4% of the respondents who were residing with someone were suffering from depression.

Table 2.

Percentage of older adults suffering from depression by their background characteristic in India.

| Background characteristic | % | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Marital status | < 0.001 | |

| Currently married | 7.8 | |

| Widowed | 10.3 | |

| Living arrangement | < 0.001 | |

| Co-residing | 8.4 | |

| Living alone | 13.6 | |

| Age | 0.207 | |

| Young-old | 8.5 | |

| Old-old | 8.4 | |

| Oldest-old | 10.9 | |

| Sex | < 0.001 | |

| Male | 7.5 | |

| Female | 9.7 | |

| Education | < 0.001 | |

| No education/primary not completed | 9.6 | |

| Primary completed | 8.1 | |

| Secondary completed | 6.1 | |

| Higher and above | 5.8 | |

| Working status | < 0.001 | |

| Working | 7.8 | |

| Retired | 10.0 | |

| Not working | 7.7 | |

| Social participation | < 0.001 | |

| No | 8.8 | |

| Yes | 6.6 | |

| Life satisfaction | < 0.001 | |

| Low | 13.2 | |

| Medium | 7.8 | |

| High | 6.0 | |

| Self-rated health | < 0.001 | |

| Good | 4.7 | |

| Poor | 13.0 | |

| Difficulty in ADL | < 0.001 | |

| No | 6.7 | |

| Yes | 15.5 | |

| Difficulty in IADL | < 0.001 | |

| No | 5.6 | |

| Yes | 12.1 | |

| Morbidity status | < 0.001 | |

| 0 | 7.2 | |

| 1 | 8.6 | |

| 2 + | 11.9 | |

| MPCE quintile | < 0.001 | |

| Poorest | 8.9 | |

| Poorer | 8.0 | |

| Middle | 8.1 | |

| Richer | 8.8 | |

| Richest | 10.1 | |

| Religion | < 0.001 | |

| Hindu | 8.6 | |

| Muslim | 9.6 | |

| Christian | 7.5 | |

| Others | 8.5 | |

| Caste | < 0.001 | |

| Scheduled Caste | 10.0 | |

| Scheduled Tribe | 5.0 | |

| Other Backward Class | 9.3 | |

| Others | 7.9 | |

| Place of residence | < 0.001 | |

| Rural | 9.7 | |

| Urban | 6.3 | |

| Region | < 0.001 | |

| North | 6.8 | |

| Central | 14.6 | |

| East | 8.3 | |

| Northeast | 5.7 | |

| West | 7.6 | |

| South | 5.9 | |

| Total | 8.7 |

%: Percentage; ADL: Activities of Daily Living; IADL: Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; p-value based on chi-square test.

Table 3 shows the results obtained from the logistic regression analysis of the socio-economic status and lifestyle determinants of depression among older adults. Model-1 represents unadjusted estimates and reveals that older adults who were widowed had higher odds to suffer from depression in reference to those older adults who were currently married [UOR: 1.41; CI 1.29, 1.55]. Older adults who were living alone had higher odds to suffer from depression in reference to those older adults who were co-residing [UOR: 1.26; CI 1.05, 1.51]. In model-2, it was found that widowed older adults were 34% significantly more likely to be depressed than currently married older adults [AOR: 1.34, CI 1.2–1.49]. Similarly, respondents who were living alone were 16 percent significantly more likely to be depressed in comparison to older adults who were co-residing [AOR: 1.16; CI 1.02, 1.40]. Model-3 represents the interaction effect of marital status along with living arrangement on depression among older adults. Older adults who were widowed and living alone were 56 percent significantly more likely to suffer from depression [AOR: 1.56; CI 1.28,1.91] in reference to older adults who were currently married and co-residing. Even older adults who were widowed and co-residing 33 percent significantly more likely to suffer from depression [AOR: 1.33; CI 1.19, 1.48] in reference to older adults who were currently married and co-residing.

Table 3.

Logistic regression estimates for older adults suffering from depression by their background characteristic in India.

| Background characteristic | Model-1 | Model-2 | Model-3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| UOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Currently married | Ref | Ref | |

| Widowed | 1.41*(1.29,1.55) | 1.34*(1.2,1.49) | |

| Living arrangement | |||

| Co-residing | Ref | Ref | |

| Living alone | 1.26*(1.05,1.51) | 1.16*(1.02,1.40) | |

| Age | |||

| Young-old | Ref | Ref | |

| Old-old | 0.79*(0.71,0.88) | 0.79*(0.71,0.88) | |

| Oldest-old | 0.71*(0.60,0.83) | 0.73*(0.62,0.83) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | Ref | Ref | |

| Female | 1.08(0.96,1.21) | 1.08(0.95,1.21) | |

| Education | |||

| No education/primary not completed | 0.95(0.76,1.19) | 0.95(0.76,1.19) | |

| Primary completed | 1.01(0.79,1.29) | 1.01(0.79,1.29) | |

| Secondary completed | 0.95(0.75,1.2) | 0.95(0.75,1.2) | |

| Higher and above | Ref | Ref | |

| Working status | |||

| Working | Ref | Ref | |

| Retired | 0.95(0.84,1.07) | 0.95(0.84,1.07) | |

| Not working | 0.77*(0.66,0.89) | 0.77*(0.66,0.89) | |

| Social participation | |||

| No | 0.91(0.73,1.12) | 0.91(0.73,1.12) | |

| Yes | Ref | Ref | |

| Life satisfaction | |||

| Low | 2.16*(1.93,2.41) | 2.16*(1.93,2.41) | |

| Medium | 1.33*(1.17,1.51) | 1.33*(1.17,1.51) | |

| High | Ref | Ref | |

| Self-rated health | |||

| Good | Ref | Ref | |

| Poor | 2.18*(1.96,2.42) | 2.18*(1.96,2.42) | |

| Difficulty in ADL | |||

| No | Ref | Ref | |

| Yes | 1.71*(1.53,1.91) | 1.71*(1.53,1.91) | |

| Difficulty in IADL | |||

| No | Ref | Ref | |

| Yes | 1.56*(1.4,1.74) | 1.56*(1.39,1.73) | |

| Morbidity status | |||

| 0 | Ref | Ref | |

| 1 | 1.20*(1.07,1.35) | 1.21*(1.07,1.35) | |

| 2 + | 1.53*(1.36,1.73) | 1.53*(1.36,1.73) | |

| MPCE quintile | |||

| Poorest | 0.76*(0.65,0.89) | 0.76*(0.65,0.89) | |

| Poorer | 0.75*(0.64,0.87) | 0.75*(0.64,0.87) | |

| Middle | 0.67*(0.57,0.78) | 0.67*(0.57,0.77) | |

| Richer | 0.85*(0.74,0.99) | 0.85*(0.74,0.98) | |

| Richest | Ref | Ref | |

| Religion | |||

| Hindu | Ref | Ref | |

| Muslim | 1.07(0.93,1.24) | 1.07(0.93,1.24) | |

| Christian | 0.94(0.74,1.22) | 0.95(0.74,1.21) | |

| Others | 1.15(0.92,1.44) | 1.16(0.92,1.45) | |

| Caste | |||

| Scheduled Caste | 1.09 (0.94,1.26) | 1.09 (0.94,1.26) | |

| Scheduled Tribe | 0.63*(0.52,0.77) | 0.63*(0.52,0.77) | |

| Other Backward Class | 1.19*(1.06,1.35) | 1.19*(1.06,1.35) | |

| Others | Ref | Ref | |

| Place of residence | |||

| Rural | Ref | Ref | |

| Urban | 1.24*(1.11,1.39) | 1.24*(1.11,1.39) | |

| Region | |||

| North | Ref | Ref | |

| Central | 2.15*(1.84,2.51) | 2.15*(1.84,2.51) | |

| East | 1.00(0.86,1.17) | 1.00(0.86,1.17) | |

| Northeast | 0.63*(0.5,0.81) | 0.63*(0.5,0.81) | |

| West | 1.23*(1.04,1.46) | 1.23*(1.04,1.46) | |

| South | 0.64*(0.54,0.76) | 0.64*(0.54,0.76) | |

| Marital status # Living arrangement | |||

| Widowed # co-residing | 1.33*(1.19,1.48) | ||

| Currently married # co-residing | Ref | ||

| Currently married # living alone | 0.54(0.12,2.32) | ||

| Widowed # living alone | 1.56*(1.28,1.91) | ||

#: Interaction; Ref: Reference; *if p < 0.05; AOR: Adjusted odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval; ADL: Activities of Daily Living; IADL: Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; Model-1 was controlled for marital status and living arrangement; Model-2 and 3 was controlled for marital status, living arrangement, age, sex, education, working status, social participation life satisfaction, self-rated health, difficulty in ADL, difficulty in IADL, morbidity status MPCE quintile, religion, caste, place of residence, region.

In model-2, it was additionally found that older adults who were not working were found to be negatively associated with depression. A lower level of life satisfaction was found to be significantly positively associated with depression [AOR: 2.16, CI 1.93–2.41]. Respondents who reported the life satisfaction as ‘low’ and ‘medium’ were 2.16 [AOR: 2.16, CI 1.93–2.41] times and 1.33 [AOR: 1.33, CI 1.17–1.51] times more likely to have depression in comparison to those who reported their life satisfaction level as ‘high’ respectively. Further, respondents who rated their health as poor were 2.18 times significantly more likely to be depressed than those who reported their health to be good [AOR: 2.18, CI 1.96–2.42]. The likelihood of getting depressed was higher among those who had difficulty with ADL activities than those who did not have any difficulty with ADL activities [AOR: 1.71, CI 1.53–1.91]. Similarly, older adults who had difficulty in IADL 56% significantly more likely to be depressed than older adults who do not have difficulty with IADL activities [AOR: 1.56, CI 1.4–1.74]. Having two and above morbidity conditions had a significant positive association with the prevalence of depression [AOR: 1.53, CI 1.36–1.73]. Older adults from the poorest wealth quintile had lower odds to suffer from depression in reference to older adults from richest wealth quintile [AOR: 0.76; CI 0.65–0.89]. Older adults from OBC had higher odds of suffering from depression in reference to older adults from others category [AOR: 1.19; CI 1.06,1.35]. Older adults from an urban place of residence had higher odds to suffer from depression in reference to older adults from rural counterparts [AOR: 1.24; CI 1.11–1.39].

Discussion

Several epidemiological studies suggest that the non-co-residential living arrangements of older adults are often associated with the prevalence of depressive symptoms7,39,40. Supporting this, our study produced similar findings, with 10.3 percent and 13.6 percent of older adults who were widowed and lived alone, respectively (against 7.8 and 8.4 percent of those currently married and co-residing) reporting severe depressive symptoms as measured by the CIDI-SF 10. The current study, using the first large nationally representative survey data of LASI, included a wide range of potential explanatory variables and adds to the few studies that have been conducted in low-income countries. Previous studies in middle- and high-income countries as well as some low-income countries like China have also observed a significant association between marital status, living arrangements and mental health among older adults41–44.

In our multivariable models, living arrangement and marital status were found to be significantly associated with depressive symptoms. These findings are parallel to studies that identified widowhood and solo living as risk factors to poor mental health among older adults in general45–48 and those who are oldest-old in particular48–51. Also, the interactive effect of marital status and living arrangement with depression was concordant with a recent study in Japan that has shown the adverse impact of both widowhood and living alone on depressive symptoms52. The possible explanation for the negative effect of widowhood on psychological wellbeing may be the increased stress due to spousal loss that results in reduced emotional support and lack of financial support53,54. Also, as documented, solo-living older individuals are less likely to have a family or close friends to talk to and are thus more likely to have a strong sense of loneliness resulting in depression55–57. On the other hand, contrary to other population-based studies58,59, older age was found to be inversely associated with depression among older adults in the present study. It can be explained in part by older persons’ reduced levels of emotional reactivity by increasing age leading to lesser reporting of symptoms of extreme distress or depression compared to their younger counterparts60. However, the increased depression associated with widowhood and solo living in older adults in our study calls for special attention from policy makers since older Indian adults are left with no or minimum social security and support.

Interestingly, the older adults who were currently in a marital union and lived alone in the present study had lower likelihood of late-life depression, as compared to married and co-residing individuals (Fig. 3). This is contrary to multiple studies showing that solo living among older individuals may lead to mental illnesses22,61. This inconsistent finding could partially be explained by the self-selection for individuals who enjoy living alone. The relatively smaller sample of older people who lived alone in our study could also have resulted in the lower odds of depression in solo living individuals due to power effects. Furthermore, consistent with existing literature, the factors identified with a linkage to the increased rates of depression in later life in this study include sex40,44, socio-economic resources62, and health status63,64. The results of the study revealed that older females and those who faced poor self-rated health, low ADL and IADL, and a higher number of diseases reported a higher rate of depressive symptoms. Findings are also in line with the evidence suggesting that the cumulative impacts of disadvantages may increase the risk for negative mental health outcomes as people grow older65,66. Consistent with past studies that have found urban–rural differences in terms of psychological wellbeing and depressive symptoms, the current results show that rural living older adults have an increased risk of depression67–69. Further, lower social class may contribute to the psychological distress among older adults due to their lack of household economic resources and financial strain70, which is supported by current finding of higher prevalence of depression among older adults from OBC category. However, the current study also observed that people from ST are at lower risk of late-life depression in comparison to ‘other’ caste category which includes castes that are considered socioeconomically advantaged. This finding suggests a need for further investigation exploring the variations in mental illnesses among different caste groups in India.

In addition, the significant association of life satisfaction with depression in our study was consistent with previous studies that have shown that older individuals who had greater life dissatisfaction were more likely to suffer from depression and suggested that such a subjective status can be promoted by enhancing their social and economic circumstances71,72. Nonetheless, the association of higher household economic status with an increased risk of depression among older adults in our study is in variance with the existing literature that shows that economic status is negatively associated with late-life depression73–75. Further studies are required to better understand the risk of developing depression among higher socio-economic groups.

There are several limitations of the present study to be acknowledged. The major limitation is the cross-sectional design of the study, eliminating the drawing of causal inferences among variables. Indeed, it is important to consider that some individuals may become lonelier because they feel depressed or lack energy. Moreover, the study is limited to older adults who are widowed or currently in a marital union. Thus, the exclusion of those who are never married/ divorced/ separated may affect the findings of the study in terms of the association of marital status with late-life depression. Importantly, in the study sample, only 5.4% of the older adults were found to be living alone. This may have led to underestimation of the association, lack of power or type II error and could also have impacted the current findings. Notwithstanding these limitations, the present study's findings provide empirical support to the body of literature that highlights the vulnerability of widowed older adults living alone.

Conclusion

The findings of the study highlight that being in a marital union and co-residential living arrangements are an essential part of mental well-being in later years of life. The study synthesized its finding with theoretical understandings of vulnerability. As in this study, older widowed women who were exposed to vulnerabilities like lower socioeconomic conditions, poor health status etc. were mainly at a higher risk of depression. Importantly, the information deriving from this study can be used to target outreach programs and service delivery for the older adults who are living alone or widowed and suffering from depression.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

Conceived and designed the research paper: S.S. and T.M.; analyzed the data: S.S. and T.M.; Contributed agents/materials/analysis tools: S.S., P.D., and T.M.; Wrote the manuscript: S.S., P.D., N.S., and T.M.; Refined the manuscript: S.S. and T.M.

Funding

No funding was received for the present study.

Data availability

The study uses secondary data which is available on reasonable request through https://www.iipsindia.ac.in/content/lasi-wave-i.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-01238-x.

References

- 1.United Nations. World Population Ageing, 2014. Dep Econ Soc Aff Popul Div.

- 2.UNFPA. Caring for Our Elders : Early Responses India Ageing Report-2017. New Delhi, India, 2017.

- 3.Guimarães RM, Andrade FCD. Healthy life-expectancy and multimorbidity among older adults: Do inequality and poverty matter? Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2020.104157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stallard E. Compression of morbidity and mortality: New perspectives. N Am. Actuar. J. 2016;20:341–354. doi: 10.1080/10920277.2016.1227269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. WHO|Life expectancy. WHO.

- 6.Sullivan AR, Fenelon A. Patterns of widowhood mortality. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2014 doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sasson I, Umberson DJ. Widowhood and depression: New light on gender differences, selection, and psychological adjustment. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2014;69:135–145. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rogers RG, Everett BG, Onge JMS, et al. Social, behavioral, and biological factors, and sex differences in mortality. Demography. 2010 doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zisook S, Shuchter SR. The first four years of widowhood. Psychiatr Ann. 1986 doi: 10.3928/0048-5713-19860501-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilcox S, Aragaki A, Mouton CP, et al. The effects of widowhood on physical and mental health, health behaviors, and health outcomes: The women’s health initiative. Heal Psychol. 2003;22:513–522. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krochalk PC, Li Y, Chi I. Widowhood and self-rated health among Chinese elders: The effect of economic condition. Australas. J. Ageing. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2007.00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moon JR, Kondo N, Glymour MM, et al. Widowhood and mortality: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2011 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agrawal G, Keshri K. Morbidity patterns and health care seeking behavior among older widows in India. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:1–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Grootheest DS, Beekman ATF, Broese Van Groenou MI, et al. Sex differences in depression after widowhood. Do men suffer more? Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 1999 doi: 10.1007/s001270050160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muhammad T, Srivastava S, Sekher TV. Association of self-perceived income status with psychological distress and subjective well-being: A cross-sectional study among older adults in India. BMC Psychol. 2021;9:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s40359-021-00588-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vable AM, Subramanian SV, Rist PM, et al. Does the ‘widowhood effect’ precede spousal bereavement? Results from a nationally representative sample of older adults. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gillen M, Kim H. Older women and poverty transition: Consequences of income source changes from widowhood. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2009 doi: 10.1177/0733464808326953. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Srivastava S, Purkayastha N, Chaurasia H, et al. Socioeconomic inequality in psychological distress among older adults in India: A decomposition analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21:1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02964-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muhammad T, Srivastava S. Why rotational living is bad for older adults evidence from a cross- sectional study in India. J. Popul. Ageing. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12062-020-09312-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zebhauser A, Hofmann-Xu L, Baumert J, et al. How much does it hurt to be lonely? Mental and physical differences between older men and women in the KORA-Age Study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2014 doi: 10.1002/gps.3998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perkins JM, Lee HY, James KS, et al. Marital status, widowhood duration, gender and health outcomes: A cross-sectional study among older adults in India. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3682-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trivedi J, Sareen H, Dhyani M. Psychological aspects of widowhood and divorce. Mens. Sana Monogr. 2009;7:37–49. doi: 10.4103/0973-1229.40648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cleveland WP, Gianturco DT. Remarriage probability after widowhood: A retrospective method. J. Gerontol. 1976 doi: 10.1093/geronj/31.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roan CL, Raley RK. Intergenerational coresidence and contact: A longitudinal analysis of adult children’s response to their mother’s widowhood. J. Marriage Fam. 1996 doi: 10.2307/353730. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Srivastava S, Muhammad T. In pursuit of happiness: Changes in living arrangement and subjective well-being among older adults in India. J. Popul. Ageing. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s12062-021-09327-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muhammad T, Meher T. Association of late-life depression with cognitive impairment: Evidence from a cross-sectional study among older adults in India. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01943-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shin SH, Kim G, Park S. Widowhood status as a risk factor for cognitive decline among older adults. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2018;26:778–787. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2018.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Do YK, Malhotra C. The effect of coresidence with an adult child on depressive symptoms among older widowed women in South Korea: An instrumental variables estimation. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2012;67:384–391. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), NPHCE, MoHFW HTHCS of PH (HSPH) and the U of SC (USC). Longitudinal Ageing Study in India ( LASI ) Wave 1, 2017–18, India Report. Mumbai. (2020).

- 30.Kessler RC, Üstün BB. The world mental health (WMH) survey initiative version of the world health organization (WHO) composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI) Int. J. Methods Psychiatric Res. 2004 doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muhammad T, Govindu M, Srivastava S. Relationship between chewing tobacco, smoking, consuming alcohol and cognitive impairment among older adults in India: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21:85. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02027-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKenna SP. Measuring patient-reported outcomes: Moving beyond misplaced common sense to hard science. BMC Med. 2011 doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Subramanian S V, Nandy S, Irving M, et al. Role of socioeconomic markers and state prohibition policy in predicting alcohol consumption among men and women in India : a multilevel statistical analysis. Bull. World Health Organ.; 019893. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Srivastava S, Singh SK, Kumar M, et al. Distinguishing between household headship with and without power and its association with subjective well-being among older adults: An analytical cross- sectional study in India. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21:304. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02256-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Osborne J, King JE. Binary Logistic Regression. In: Best Practices in Quantitative Methods. SAGE Publications, Inc., 2011, pp. 358–384.

- 36.Webster A. Heteroscedasticity. In: Introductory Regression Analysis. (2020). 10.4324/9780203182567-12.

- 37.Alin A. Multicollinearity. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Comput Stat. (2010). 10.1002/wics.84.

- 38.StataCorp. Stata: Release 14. Statistical Software. 2015.

- 39.Lee SE, Hong GRS. Predictors of depression among community-dwelling older women living alone in Korea. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2016;30:513–520. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin PC, Wang HH. Factors associated with depressive symptoms among older adults living alone: An analysis of sex difference. Aging Ment. Heal. 2011;15:1038–1044. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2011.583623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Su D, Wu XN, Zhang YX, et al. Depression and social support between China’ rural and urban empty-nest elderly. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2012;55:564–569. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hu Y, Ruiz M, Bobak M, et al. Do multigenerational living arrangements influence depressive symptoms in mid-late life? Cross-national findings from China and England. J. Affect Disord. 2020;277:584–591. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fried EI, Bockting C, Arjadi R, et al. From loss to loneliness: The relationship between bereavement and depressive symptoms. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2015;124:256–265. doi: 10.1037/abn0000028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perrig-Chiello P, Spahni S, Höpflinger F, et al. Cohort and gender differences in psychosocial adjustment to later-life widowhood. J. Gerontol Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2016;71:765–774. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbv004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bennett KM. Longitudinal changes in mental and physical health among elderly, recently widowed men. Mortality. 1998;3:265–273. doi: 10.1080/713685953. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bennett KM, Smith PT, Hughes GM. Coping, depressive feelings and gender differences in late life widowhood. Aging Ment. Heal. 2005;9:348–353. doi: 10.1080/13607860500089609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jeon GS, Choi K, Cho SI. Impact of living alone on depressive symptoms in older Korean widows. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2017 doi: 10.3390/ijerph14101191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith KJ, Victor C. Typologies of loneliness, living alone and social isolation, and their associations with physical and mental health. Ageing Soc. 2019;39:1709–1730. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X18000132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jakobsson U, Hallberg IR, Westergren A. Overall and health related quality of life among the oldest old in pain. Qual. Life Res. 2020;13:125–136. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000015286.68287.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen F, Short SE. Household context and subjective well-being among the oldest old in China. J. Fam. Issues. 2008;29:1379–1403. doi: 10.1177/0192513X07313602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ng ST, Tey NP, Asadullah MN. What matters for life satisfaction among the oldest-old? Evidence from China. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakagomi A, Koichiro S, Hanazato M, et al. Does community-level social capital mitigate the impact of widowhood & living alone on depressive symptoms?: A prospective, multi-level study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020;259:113140. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ansari S, Muhammad T, Dhar M. How does multi—morbidity relate to feeling of loneliness among older adults evidence from a population—based survey in India. J. Popul. Ageing. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s12062-021-09343-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Srivastava S, Shaw S, Chaurasia H, et al. Feeling about living arrangements and associated health outcomes among older adults in India: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-10013-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Henning-Smith C. Quality of life and psychological distress among older adults: The role of living arrangements. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2016;35:39–61. doi: 10.1177/0733464814530805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.United Nations. World Population Ageing 2017 report. 2017.

- 57.Yeh SCJ, Lo SK. Living alone, social support, and feeling lonely among the elderly. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2004;32:129–138. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2004.32.2.129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Taqui AM, Itrat A, Qidwai W, et al. Depression in the elderly: Does family system play a role? A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-7-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kamble SV, Dhumale GB, Goyal RC, et al. Depression among elderly persons in a primary health centre area in Ahmednagar, Maharastra. Indian J. Public Health. 2009;53:253–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carr D, Bodnar-Deren S. Gender, Aging and Widowhood. Int. Handbook Popul. Aging. 2009 doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-8356-3_32. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jadhav A, Weir D. Widowhood and depression in a cross-national perspective: Evidence from the United States, Europe, Korea, and China. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2018;73:e143–e153. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbx021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Domènech-Abella J, Mundó J, Leonardi M, et al. The association between socioeconomic status and depression among older adults in Finland, Poland and Spain: A comparative cross-sectional study of distinct measures and pathways. J. Affect Disord. 2018;241:311–318. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.08.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Koster A, Bosma H, Kempen GIJM, et al. Socioeconomic differences in incident depression in older adults: The role of psychosocial factors, physical health status, and behavioral factors. J. Psychosom. Res. 2006;61:619–627. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Won S, Kim H. Social participation, health-related behavior, and depression of older adults living alone in Korea. Asian Soc. Work Policy Rev. 2020;14:61–71. doi: 10.1111/aswp.12193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dannefer D. Cumulative advantage/disadvantage and the life course: Cross-fertilizing age and social science theory. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2003;58:327–337. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.6.s327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gonyea JG, Curley A, Melekis K, et al. Loneliness and depression among older adults in urban subsidized housing. J. Aging Health. 2018;30:458–474. doi: 10.1177/0898264316682908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dong XQ, Simon MA. Health and aging in a Chinese population: Urban and rural disparities. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2010;10:85–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2009.00563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bergdahl E, Allard P, Lundman B, et al. Depression in the oldest old in urban and rural municipalities. Aging Ment. Heal. 2007;11:570–578. doi: 10.1080/13607860601086595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sasaki Y, Shobugawa Y, Nozaki I, et al. Association between depressive symptoms and objective/subjective socioeconomic status among older adults of two regions in Myanmar. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jensen R. Caste, culture, and the status and well-being of widows in India. Anal. Econ. Aging. 2005;I:357–376. doi: 10.7208/chicago/9780226903217.003.0012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lue BH, Chen LJ, Wu SC. Health, financial stresses, and life satisfaction affecting late-life depression among older adults: A nationwide, longitudinal survey in Taiwan. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2010;50(Suppl 1):S34–S38. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4943(10)70010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Reyes Fernández B, Rosero-Bixby L, Koivumaa-Honkanen H. Effects of self-rated health and self-rated economic situation on depressed mood via life satisfaction among older adults in costa rica. J. Aging Health. 2016;28:225–243. doi: 10.1177/0898264315589577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kong FL, Hoshi T, Ai B, et al. Association between socioeconomic status (SES), mental health and need for long-term care (NLTC)-A longitudinal study among the Japanese elderly. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2014;59:372–381. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2014.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kong F, Xu L, Kong M, et al. The relationship between socioeconomic status, mental health, and need for long-term services and supports among the Chinese elderly in shandong province—A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019;16:1–19. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16040526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ng CWL, Tan WSH, Gunapal PPG, et al. Association of socioeconomic status (SES) and social support with depressive symptoms among the elderly in Singapore. Ann. Acad. Med. Singapore. 2014;43:576–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The study uses secondary data which is available on reasonable request through https://www.iipsindia.ac.in/content/lasi-wave-i.