Abstract

Circadian clocks are ubiquitous timing mechanisms that generate approximately 24-h rhythms in cellular and bodily functions across nearly all living species. These internal clock systems enable living organisms to anticipate and respond to daily changes in their environment in a timely manner, optimizing temporal physiology and behaviors. Dysregulation of circadian rhythms by genetic and environmental risk factors increases susceptibility to multiple diseases, particularly cancers. A growing number of studies have revealed dynamic crosstalk between circadian clocks and cancer pathways, providing mechanistic insights into the therapeutic utility of circadian rhythms in cancer treatment. This review will discuss the roles of circadian rhythms in cancer pathogenesis, highlighting the recent advances in chronotherapeutic approaches for improved cancer treatment.

Subject terms: Circadian rhythms, Targeted therapies

Cancer: Reviewing the role of circadian rhythm

Therapies that reset the body’s circadian clock could prove valuable in treating multiple cancers. Chronic disruption to circadian rhythm by genetic and environmental factors such as frequent jet lag is associated with increased susceptibility to diseases, particularly cancer. Yool Lee at Washington State University in Spokane, USA, reviewed understanding of clock dysregulation in cancers and the promising application of novel ‘chronotherapies’. Disruption to the molecular crosstalk between clock mechanisms and cell cycles (including cell death and immune pathways) can allow cancer cells to take hold. Rhythm disruption also modulates the activity of tumor suppressors and cancer-promoting genes, and can even trigger anti-cancer drug resistance. Training the clock via light therapy, exercise, and administering chemotherapy drugs at specific times of day may prove valuable, while drugs that affect the circadian clock also show promise.

Introduction

Circadian clocks are cell-autonomous timing systems that generate approximately 24-h periodic rhythms that are conserved in nearly all life, from unicellular organisms to humans. These internal timing systems integrate diverse environmental (e.g., light) and metabolic (e.g., food intake) stimuli to regulate biological activities, including sleep/wake, energy metabolism, hormonal and immune functions, and cell proliferation1. Disturbances in these rhythms caused by sleep deprivation, eating at night, or chronic jet lag are closely associated with the development of sleep and mood disorders, obesity, diabetes, and cancers2. In particular, genetic and environmental perturbations of circadian rhythms largely alter the expression and activity of several tumor suppressors and oncogenes in both host and tumor tissues to favor cancer incidence and progression3,4. Circadian disruptions can also reprogram host metabolism and immune systems, fostering an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in multiple cancer types5,6. Due to such roles in cancer onset and progression, circadian rhythms have been an emerging target for cancer prevention and treatment. In recent years, growing numbers of studies have investigated the idea of exploiting circadian clocks for cancer therapy by enhancing circadian rhythms, modulating the activity of circadian clock molecules, and optimizing the timing of anticancer drugs according to the host or tumor circadian rhythms7. In this review, we will discuss additional details regarding the link between circadian clocks and cancer pathways, highlighting treatment strategies that exploit multiple chronophysiological mechanisms.

Mechanism of circadian physiology

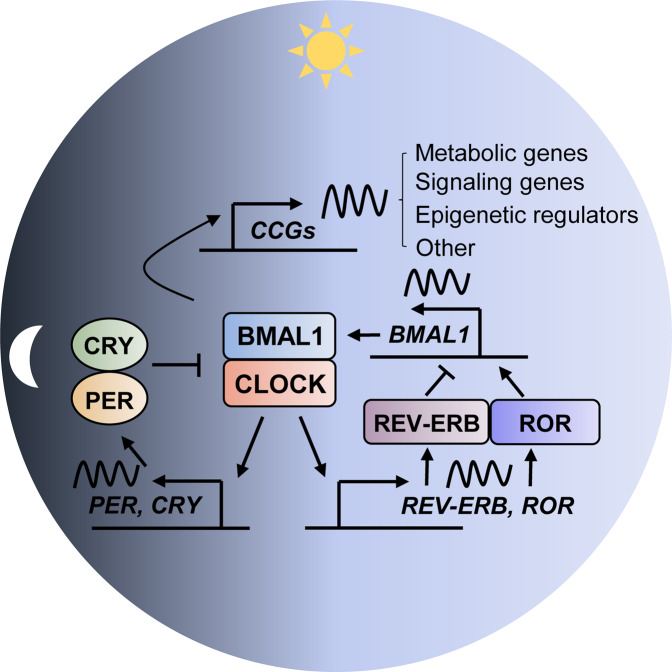

The basic architecture of circadian rhythm mechanisms across living species on earth is typically characterized by a cell-autonomous autoregulatory feedback loop8. In eukaryotes, a subset of dedicated positive and negative clock regulators forms the interlocked transcriptional translational feedback loop to constitute a cell-autonomous oscillator that drives the rhythmic expression of output genes involved in metabolic, biosynthetic, signal transduction, and cell cycle pathways8,9. In mammals, the BMAL1 and CLOCK transcriptional activator complex cyclically drive the transcription of its own repressors, period (PER), and cryptochrome (CRY). The core oscillator is complemented by a second loop in which periodic expression of BMAL1 is maintained by the REV-ERBα/β repressor and retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor (ROR) α/β activator proteins10 (Fig. 1). In addition to the core regulatory loops, multiple levels of epigenetic, posttranscriptional, and posttranslational regulation that involve various kinases and phosphatases, ubiquitin–proteasome pathway components, nuclear–cytoplasmic transporters, noncoding RNAs, and chromatin remodelers contribute to the molecular clockwork, thus coordinating temporal programs via multiple clock-output genes8,11,12. This molecular clockwork is shared across the brain and peripheral organ systems, constituting a body-wide circadian network.

Fig. 1. Circadian molecular clock mechanism.

This autoregulatory feedback loop cycles between the CLOCK/BMAL1 transcriptional activator complex and its repressors (PER/CRY, REV-ERBα) or activators (RORα/β) to constitute the molecular clock oscillator that drives the expression of multiple clock-controlled genes (CCGs), such as metabolic genes, signaling genes, and epigenetic regulators.

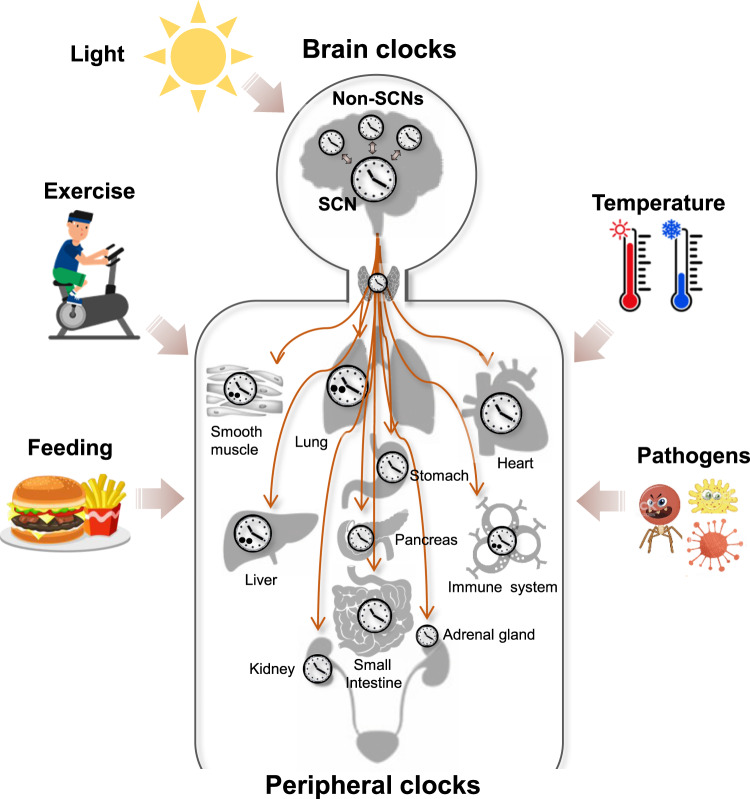

In the brain, intracellular oscillators in approximately 20,000 individual neurons and astrocytes comprise the hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), a central circadian pacemaker13. The principal role of the SCN clock is to communicate retinal light information received from the retinohypothalamic tract (RHT) to peripheral clock systems, thus mediating the periodic synchronization of internal body rhythms with external day and night cycles1. In a hierarchical organization model, the SCN master clock orchestrates circadian phases in non-SCN subordinate brain clocks via rhythmic release of neurotransmitters and neuropeptides, as well as in peripheral organ clocks via systemic hormonal secretion and neural innervations, thereby coordinating rhythmic output physiology and behaviors with daily environmental changes14 (Fig. 2). For example, the SCN coordinates the rhythmic, antiphasic secretion of the night sleep hormone melatonin from the pineal gland with the release of the morning stress hormone GC from the adrenal glands via the sympathetic nervous system to ensure daily rhythms in sleep/wake, as well as neural, metabolic, and immune functions1. In addition, the brain master clock controls other peripheral clock functions in the heart, kidney, pancreas, lung, intestine, and thyroid glands through circadian modulation of the autonomic nervous system14.

Fig. 2. Circadian clock systems.

The SCN central clock in the brain, primarily entrained by light, orchestrates circadian phases not only in non-SCN subordinate brain clocks via rhythmic release of neurotransmitters and neuropeptides but also in peripheral organ clocks via systemic hormonal secretion and neural innervations. Nonphotic external cues (e.g., temperature changes, food intake, exercise, and pathogens) can reset circadian rhythms in peripheral clock tissues, thereby influencing rhythmic output physiology and behaviors.

In addition to SCN-dependent clock entrainment, non-SCN brain regions and peripheral tissues possess their own autonomous and multistimuli entrainable oscillators that influence not only circadian functions in the SCN and neighboring local clocks but also behavioral rhythms via neural, hormonal, and metabolic feedback mechanisms15,16. Moreover, multiple nonphotic physiological (e.g., redox cofactors, reactive oxygen species, microbial products) and environmental (e.g., temperature, food intake, exercise, and pathogenic infections) cues control extra-SCN brain and peripheral clock functions, which, in turn, impact the entire host clock system via neural and immunometabolic circuits17–19. These findings suggest that real-world circadian rhythms are achieved through multimode regulation of tightly coupled body clocks under daily changes in internal and external processes.

Circadian disruption and cancer pathogenesis

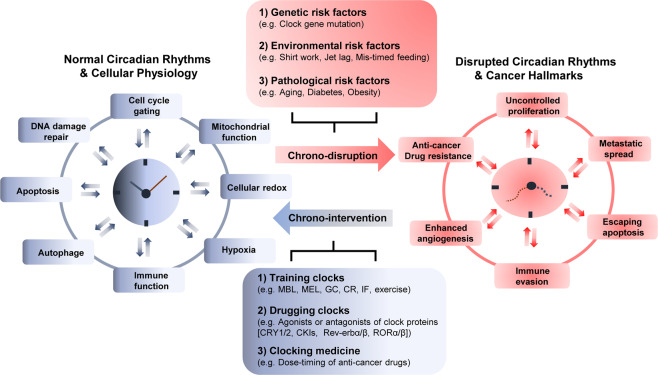

The growing knowledge of chronobiological mechanisms has increased our understanding of how rhythm disturbances by multiple physiological and environmental factors impact pathogenesis in diseases such as cancer (Fig. 3). Disrupted circadian rhythmicity has been a prominent feature of modern society since the invention of artificial light sources. Indeed, 80% of the world’s population is now exposed to light during the night, and approximately 18–20% of workers in the USA and Europe are involved in night or rotating shift work, making them vulnerable to multiple rhythm disorders, including cancer20. Several epidemiological studies further suggest that night shift work or chronic jet lag increases the risk of the incidence and development of the most common cancer types (i.e., breast, lung, prostate, colorectal, and skin cancers)2. Based on this evidence, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified “shift-work that involves circadian disruption” as potentially “carcinogenic to humans (Group 2A)” in 2007 and again in 201921.

Fig. 3. Chronodisruptive factors and chronotherapeutic interventions in cancer pathogenesis and treatment.

Circadian clocks reciprocally interact with multiple pathways involved in cellular homeostasis and metabolism. Circadian rhythm disruptions caused by genetic, environmental, and pathological risk factors promote cancer onset and progression characterized by cancer hallmarks. Conversely, several types of chronotherapeutic interventions can enhance or restore circadian rhythms to reduce cancer pathogenesis and improve the response to anticancer treatment. MBL morning bright light, MEL melatonin, GCs glucocorticoids, CR caloric restriction, IF intermittent fasting.

The results from several studies of animal models exposed to forced circadian desynchrony regimens have also reinforced the causal relationship between circadian disturbances and cancer pathogenesis. In an earlier mouse model study, SCN ablation or exposure to experimental chronic jetlag (CJL, consisting of an 8-h advance of the light-dark cycle every 2 days) was shown to cause alterations in circadian physiology and significantly accelerate the growth rates of transplanted tumors (Glasgow osteosarcoma and pancreatic adenocarcinoma)22. Subsequent animal studies showed that circadian rhythm disruptions induced by CJL promoted lung tumor growth and progression with altered immune functions4,23. Furthermore, CJL conditions have been observed to accelerate tumor cell cycle progression and growth rates in carcinogen-induced tumors as well as grafted melanomas in mice3. In line with these results, another murine melanoma model study reported that circadian disruption facilitates tumor-immune microenvironment remodeling that favors tumor cell proliferation6. More recently, chronic circadian disruption has also been shown to promote breast cancer cell dissemination and metastasis in mice by increasing the stemness and tumor-initiating potential of tumor cells and by creating an immunosuppressive shift in the tumor microenvironment5.

Roles of circadian clock components in cancer

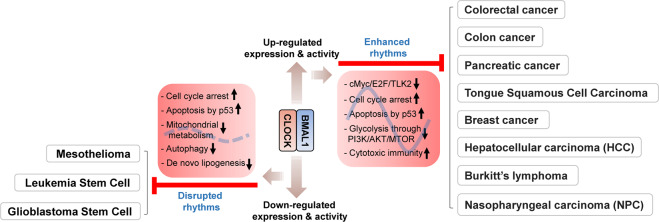

At the molecular and cellular levels, there is close crosstalk between the circadian clock machinery and the cell cycle, DNA repair, apoptosis, senescence, autophagy, and other oncogenic and immune pathways7. Circadian perturbations dysregulate these processes, leading to uncontrolled proliferation, escape from apoptosis, metastatic spread, immune evasion, enhanced angiogenesis, and anticancer drug resistance, which are all hallmarks of cancer24 (Fig. 3). In this regard, multiple loss- and gain-of-function studies with cellular and animal models have demonstrated the direct involvement of clock genes in cancer predisposition and development. Epigenetic or genetic inactivation of Bmal1 and/or Clock has been shown to increase tumor proliferation or growth rates in several types of cancer, such as hematologic cancer25, colon cancer26, pancreatic cancer27, tongue squamous cell carcinoma (TSCC)28, breast cancer29, lung adenocarcinoma4, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)30, nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC)31, and glioblastoma (GBM)32. Conversely, overexpression of these circadian activators suppresses proliferative and malignant phenotypes in tumor cells via mechanisms involving cell cycle arrest and p53-dependent apoptosis32,33. Similarly, downregulation or upregulation of Per1, Per2, and Cry1, the principal target genes of BMAL1/CLOCK, has been shown to promote or suppress tumor incidence and proliferation, respectively, in multiple cancer cell types, including Lewis lung carcinoma and mammary carcinoma cells34, pancreatic cancer35, lung carcinoma4, leukemia36,37, glioma38, ovarian cancer39, and oral squamous cell carcinoma40,41. The potential anticancer mechanism exerted by PER1/2 has been suggested to involve the inhibition of PI3K/AKT/mTOR-mediated glycolysis as well as cell cycle arrest and apoptosis induction34,40,41. As an additional tumor-controlling mechanism, the Lamia group has reported that CRY1 and/or CRY2 promote the degradation of cMYC, early 2 factors (E2F) family members, and tousled-like kinase 2 (TLK2) by recruiting these cell cycle-related oncogenic factors to the SCFFBXL3 ubiquitin-ligase complex42. Consistent with these results, a recent large-scale systems analysis of 32 human cancer types revealed that PERs and CRYs, among several other clock genes, are downregulated in multiple cancers43. Overall, these findings highlight the tumor suppressor functions of canonical clock components in most cancer types (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Divergent roles of circadian clock components in cancer.

Enhanced levels or activity of circadian clock components (e.g., CLOCK/BMAL1) inhibit tumor proliferation and growth by promoting the degradation of oncoproteins (e.g., cMYC, E2F, and TLK2), cell cycle arrest, apoptotic cell death, metabolic defects, and cytotoxic immunity in multiple cancers, as indicated. On the other hand, the core clock components may also exert tumor-suppressive functions in some cancer cell types (e.g., mesothelioma, leukemia stem cells, glioblastoma stem cells) by inhibiting tumor progression upon downregulation. E2F early 2 factor, TLK2 tousled like kinase 2.

On the other hand, some studies show that the core clock genes exert tumor promotive functions, depending on the cancer cell status or type. For example, BMAL1 silencing was observed to lead to a substantial increase in apoptosis with mitotic and morphological abnormalities in malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) cells44. Similarly, knockdown of either BMAL1 or CLOCK has been observed to induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in cancer stem cells (CSCs) in patient-derived GBM45 or murine leukemia stem cells (LSCs) in acute myeloid leukemia (AML)46. Furthermore, a recent study showed that BMAL1 overexpression promotes breast cancer cell invasion and metastasis by upregulating the expression of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9), a mediating factor for local invasion and distant metastasis of tumors47. More recently, CRY1 has been suggested to be a critical factor for efficient DNA repair in tumors, acting as a protumorigenic factor48. This is reminiscent of previous studies showing that knockout of Cry1/2−/− in mice enhances apoptosis pathways in genotoxic responses to UV or cisplatin, a DNA damaging agent, by causing increased expression of the proapoptotic Factor p7349. The tumor-promoting function of CRY1 has been further suggested in a recent study showing that CRY1 enhances p53 tumor suppressor degradation via p53 binding to its ubiquitin E3 ligase MDM2 proto‑oncogene in bladder cancer cells, thereby increasing anticancer drug sensitivity50. Altogether, these results suggest divergent roles of circadian clock genes in tumor pathogenesis depending on the type and/or state of the cell (Fig. 4).

Targeting circadian rhythms in cancer treatment

Further insights into circadian rhythms and their related diseases have ignited growing interest in how these processes can be utilized to improve cancer prevention and treatment. In a recent review article, Sulli et al. nicely categorized chronotherapeutic approaches into three types: (1) training the clock: interventions to enhance or maintain a robust circadian rhythm in feeding-fasting, sleep-wake, or light–dark cycles; (2) drugging the clock: using small-molecule agents that directly target a circadian clock; and (3) clocking the drugs: optimizing the timing of drugs to improve efficacy and reduce adverse side effects51 (Fig. 3). These chronobiological concepts are not exclusive to each other but have been applied to cancer treatment in a combinatory manner. For example, training the clock can be implemented to strengthen the compromised or disordered rhythms, thus improving the effects of clocked drugs or drugging the clock. With these strategies in mind, in the following sections, we describe recent chronobiological approaches in cancer therapy.

Training circadian clocks for cancer treatment

Based on the rhythm entrainment mechanism by photic stimuli, morning bright light (MBL) exposure has been widely implemented to cure sleep problems (e.g., advanced or delayed sleep phase syndromes), neuropsychiatric diseases (e.g., autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and dementia), and metabolic disorders (e.g., diabetes and obesity) in preclinical or clinical settings52. In line with this, light therapy has been an emerging chronotherapeutic tool to mitigate cancer progression. Accumulated studies with a human cancer xenograft model have revealed that daytime blue light enhances nighttime circadian melatonin inhibition of tumor growth in prostate, liver, and breast cancers53,54. These results correspond with previous reports showing that melatonin depletion by light exposure late at night stimulates the growth of multiple human cancer xenografts and increases anticancer drug resistance55,56. Other experimental human studies with a simulated night shift work model have shown that bright light induces complete and rapid adjustment of peripheral clocks, suggesting that phototherapy may be a potential nonpharmacological intervention to counteract the progressive effects of shift work or jet lag on tumors57,58. Overall, these studies suggest that targeting the brain–neurohormone axis holds promise for achieving multiple therapeutic benefits in cancer prevention and treatment via the improvement or correction of circadian rhythms.

In recent studies, nutritional interventions have been increasingly thought to improve circadian rhythms and health59. Indeed, mouse studies have revealed that circadian molecular and metabolic profiles altered by aging are reverted by caloric restriction (CR), a well-known antiaging dietary intervention60. In addition to its antiaging benefits, increasing preclinical evidence indicates that CR may have anticancer effects by reducing tumor progression, enhancing the death of cancer cells, and elevating the effectiveness and tolerability of chemo- and radiotherapies61. Nonetheless, it is increasingly recognized that chronic CR often has detrimental effects on tumor development and chemotherapy in cancer patients, possibly by negatively affecting the immune system, wound healing, and other important functions62. As an alternative, intermittent fasting (IF), a diet-based therapy that alternates between fasting and free feeding/eating for a period of time, has been reported to inhibit tumor growth and improve antitumor immune responses in preclinical and clinical studies63. Furthermore, IF can increase cancer sensitivity to chemotherapy and radiotherapy and reduce the side effects of traditional anticancer treatments63. Taken together, this body of evidence suggests that well-designed chronodietary intervention holds promise as a potential therapeutic regimen to counter cancer, with fewer side effects and more safety.

Along with diet, exercise is gaining emerging attention as a potential chronotherapeutic intervention strategy for the prevention and treatment of multiple disease processes17. Notably, increasing numbers of human studies have revealed the therapeutic benefits of exercise in cancer treatment and survival64. Compared to mice treated with chemotherapy alone, mice treated with exercise plus chemotherapy presented with delayed tumor growth in models of breast cancer, melanoma, and pancreatic cancer64. However, most of these studies were performed without considering the effects of exercise timing on these disease processes. In this regard, a recent, population-based, case-control study reports that those who exercise in the early morning may have reduced risks of developing prostate or breast cancer than those who exercise in the evening65. In the future, it would be interesting to investigate how the timing of exercise influences cancer progression and chemotherapeutic outcomes with more mechanistic approaches.

In parallel with nonpharmacological interventions, several experimental and clinical studies have suggested that melatonin is an effective anticancer hormone beyond its circadian entrainment function66. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials revealed that low secretion of melatonin is associated with a higher incidence of cancer development in patients with exposure to light during nighttime hours67. Moreover, melatonin has the capacity to act specifically on cancer cells, not on normal cells68. Melatonin also reduces chemotherapy‐induced toxicity on normal cells through the re‐establishment of the light/dark circadian rhythm69. These results hold promise for establishing melatonin therapy as one of the safest chronobiotic strategies in the treatment of cancer.

Similar to melatonin, glucocorticoids (GCs) are also anticancer hormones. GCs are steroid hormones that are rhythmically secreted from the adrenal gland via SCN modulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal stress response axis70. GC levels peak in the morning as a strong circadian cue to reset the peripheral tissue clock, and they have a systemic influence on metabolic (e.g., gluconeogenesis) and immune (e.g., anti-inflammatory) functions70. The synthetic GC steroid dexamethasone (Dex) has been used as a supportive care comedication for cancer patients undergoing standard care pemetrexed/platinum doublet chemotherapy71. In particular, GCs have been very effective in the treatment of lymphoid malignancies, including leukemia, lymphomas, and MM, with much work being done to enhance their effects and overcome resistance72. Interestingly, a recent animal study showed that enhancing the circadian clock with Dex treatment reduced tumor proliferation and growth in mouse melanoma73. Despite their tumor suppressor function, recent clinical reports suggest that GCs may also be implicated in poorer responses to cancer therapies with immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as anti-PD-(L)1, due to their immunosuppressive functions74. Given the diurnal fluctuation in endogenous GC levels, it would therefore be important to consider the dose and administration timing of corticosteroids to improve efficacy and safety in their use with immune-based cancer therapies.

Drugging clocks for cancer treatment

In recent years, the identification of a growing number of small molecules that modulate circadian rhythms by targeting core or noncore clock proteins has expanded the treatment windows and options for patients with diverse clock-related disorders75. Casein kinases 1δ and 1ε (CK1δ/ε) are critical components of the circadian clockwork that determine the circadian period and re-entrainment kinetics via phosphorylation of PERs to regulate their timed nuclear entry and activity76. Recently, casein kinases have been suggested to be pro-oncogenic proteins that are emerging as therapeutic targets in cancer77. For example, a series of potent and selective CK1δ/ε inhibitors have been shown to have an antitumor effect in the treatment of breast cancer both in vitro and in vivo78. Likewise, the CK1δ/ε inhibitor IC261 decreases cell survival and proliferation and increases apoptosis in colon, liver, and other human cancer cells, involving multiple oncogenic mechanisms79. In addition to studies targeting the CK1 family, more recent cell-based screens have identified a novel, potent, and highly selective CK2 inhibitor (GO289) that was demonstrated to strongly lengthen the circadian period and inhibit the growth of human and mouse cancer cells80. In line with these findings, several preclinical and clinical studies have shown that multiple anticancer drugs (e.g., umbralisib and CX-4945) targeting the CK1 or CK2 family exhibit unique immunomodulatory effects in the treatment of hematological cancers, such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia, other non-Hodgkin lymphomas, myelodysplastic syndrome, AML and multiple myeloma (MM)81,82. Collectively, these results suggest that targeting CK family members is a promising therapeutic avenue for the treatment of various forms of cancer.

Similarly, growing evidence suggests that pharmacological targeting of REV-ERBs may have therapeutic potential in a wide range of neuropsychiatric, metabolic, and immune disorders, as well as cancers. Synthetic REV-ERB agonists, such as SR9009 and SR9011, induce wakefulness, suppress sleep, regulate emotional behavior, and reduce anxiety-like behavior in mice83. Notably, recent in vitro and in vivo studies have revealed that REV-ERB agonists (SR9009 and SR9011) exhibit selective anticancer properties in brain, leukemia, breast, colon, and melanoma cancer cell lines by inhibiting autophagy and de novo lipogenesis important for cancer cell survival45,84,85. The antitumor effect of the REV-ERB agonist SR9009 was further confirmed by subsequent studies showing that treatment with this drug significantly reduced cell proliferation and viability in glioma cells as well as chemoresistant and chemosensitive small-cell lung carcinoma cells by impairing autophagy86,87.

Additional potential targets for treating cancer include several ROR isoforms and positive transcriptional regulators of Bmal1 expression. Notably, emerging studies report that pharmacological inhibition of RORγ in vitro and in vivo exerts potent antitumor activity in multiple cancer types, such as castration-resistant prostate cancer88, pancreatic adenocarcinoma89, and triple-negative breast cancer90. On the other hand, synthetic RORγ agonists have also been reported to enhance antitumor immunity by increasing cytotoxic lymphocyte functions and attenuating immunosuppressive mechanisms91. Indeed, the ROR agonist LYC-55716 has been actively implemented in preclinical and clinical trials, showing good tolerability, safety, and pharmacokinetics in single or combined treatment with existing immunotherapeutic agents74. Notably, nobiletin, a dietary flavonoid found in citrus fruits, has been recently characterized as an agonist of RORα and RORγ that can induce apoptosis and cell cycle arrest, suppress migration and invasion, inhibit many oncogenic drivers, upregulate tumor suppressors, and increase chemotherapy sensitivity across several cancer cell types92. These results suggest that ROR isoforms may be a promising target for the treatment of cancers.

Increasing numbers of reports have suggested a potential role for CRY modulators in metabolic disease and cancer treatments. Hirota and colleagues first reported that KL001, a CRY stabilizer identified via cell-based high-throughput circadian assays, was found to lengthen the circadian period in a variety of cells and tissues and block glucagon-dependent induction of gluconeogenesis in cultured hepatocytes93. Remarkably, in a recent study, KL001 exhibited antitumor activity, such as impaired self-renewal, cell migration, and proliferation, as well as increased apoptosis, in patient-derived GBM stem cells45. However, another study showed that KL001 promoted cancer cell migration but had no effects on cell proliferation or colony formation in U2OS human osteosarcoma cells94. Interestingly, the CRY1/2 inhibitor KS15 has been reported to reduce MCF-7 cell growth and increase chemosensitivity in human breast cancer cells, possibly via the drug-induced elevation of PER2, a tumor suppressor clock protein95. These findings suggest that the antitumor effects of CRY modulators in cancer cells involve divergent mechanisms that are cell type-specific.

Clocking medicine for cancer treatment

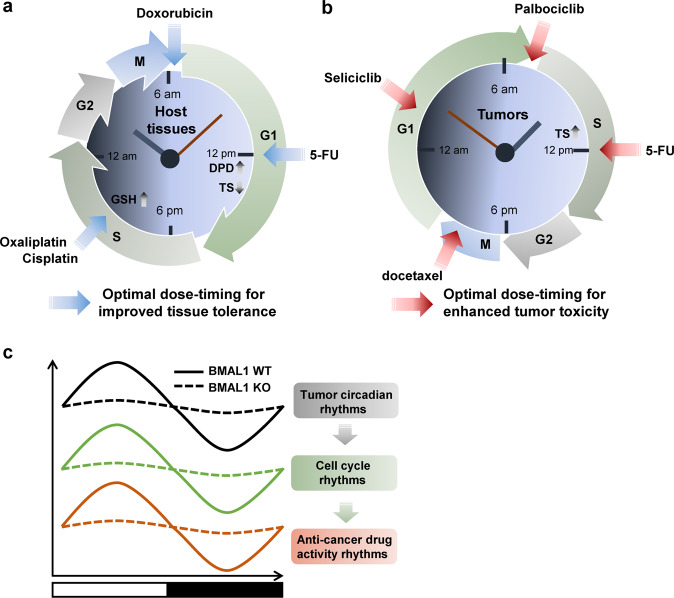

It has been well documented that circadian clocks regulate the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination of drugs96. Furthermore, growing experimental and clinical evidence suggests that the circadian timing of medicine can be an important parameter in disease treatment, including chemotherapy7. Numerous clinical studies have shown that the efficacies of over 30 chemotherapy drugs can vary by over 50% depending on when they are administered97. Due to the cytotoxic effects of anticancer drugs on normal tissues as well as malignant cells, a major goal of chronocancer therapeutic studies is to reduce the toxicity that results in host tissue damage and immunological dysfunction (Fig. 5a). Early human studies in patients with advanced ovarian cancer showed that administration of doxorubicin in the morning (e.g., at 6 am) and cisplatin in the evening (e.g., at 6 pm before or after doxorubicin) caused fewer complications and less renal toxicity, along with dose reductions and treatment delays, when compared with administration of doxorubicin in the evening and cisplatin in the morning98,99. Likewise, in several clinical trials with patients with metastatic colorectal cancer, chronotherapy with irinotecan, oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), and leucovorin in combination resulted in advantages in time to progression and overall survival, with increased tolerability and safety compared to routine chemotherapy100.

Fig. 5. Circadian timing of cancer medicine.

The purpose of chronotherapy in anticancer medicine is to improve host tolerance and safety (a) or tumor cytotoxicity (b). a Chronotissue tolerance in anticancer therapy. The antiphasic peak and trough levels of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD), an elimination enzyme of 5-FU, and thymidine synthase (TS) in host tissues are associated with reduced toxicity with 5-FU treatment. Daily variation in the levels of glutathione (GSH), a potent antioxidant, is another host chronotolerance biomarker to consider when platinum-based anticancer drugs (e.g., oxaliplatin and cisplatin) are used. For example, doxorubicin is more effective and causes fewer side effects with morning treatment. b Chronotumor toxicity of antitumor agents. Daily rhythms in the tumor-specific cell cycle can be targeted by various cell cycle-specific anticancer drugs, including those that target the G1 phase (seliciclib), G–S phase transition (palbociclib), S phase (5-FU), and M phase (docetaxel). G; cell growth, S; DNA synthesis, M; mitosis. c Circadian regulation of the time-of-day specificity of antitumor drugs. Circadian clock function in tumors regulates cell cycle rhythms that mediate the dose-time-dependent cytotoxicity of antitumor drugs. Genetic ablation of BMAL1 (BMAL1 KO; dashed line) in tumors abolishes cell cycle rhythms and the time-of-day-specific drug sensitivity present in intact tumor cells (BMAL1 WT; solid line).

Importantly, extensive studies have unraveled potential mechanisms underlying chronomodulated chemodrug safety. Computational analysis with experimental and clinical results has revealed that the same temporal pattern of drug (e.g., 5-FU and oxaliplatin) administration can result in minimal cytotoxicity in one cell population (e.g., normal cells), while at the same time, it can display high cytotoxicity in another cell population (e.g., tumor cells)101. These analyses underscore a potential advantage of chronotherapy in improving the simultaneous chronotolerance and chronoefficacy of anticancer drugs. For example, at the molecular level, the rhythmic response and toxicity of 5-FU are dependent upon circadian oscillations in thymidylate synthase activity, its molecular target, and dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase activity (DPD), the rate-limiting enzyme responsible for its elimination102,103. In line with this, a recent clinical study has shown that circadian oscillation of the DPD enzyme, with the peak of activity occurring at 4 pm and the trough of activity occurring at 4 am, modulates the time-dependent bioavailability and efficacy of 5-FU104. Moreover, the levels of glutathione (GSH), an antioxidant tripeptide involved in drug detoxification, were also found to fluctuate daily, with peak concentrations occurring in the afternoon (~4 pm); therefore, platinum drug (e.g., cisplatin and oxaliplatin) toxicities were reduced when they were administered within the peak GSH time window105. Indeed, current knowledge of these circadian mechanisms has been widely leveraged to design and implement recent clinical trials, such as the induction of chronomodulated chemotherapy with 5-FU or cisplatin plus radiotherapy for NPC, with growing results showing reductions in adverse effects and enhanced tolerance with thoughtful, timed treatment approaches106.

In addition to host circadian rhythms, it has been suggested that daily cell-cycle dynamics in tumors can also be targeted for the time-of-day efficacy of anticancer therapy (Fig. 5b). In particular, cell cycle rhythm has been considered one of the most determinant factors in chronocancer therapy since 24-h mitotic rhythmicity was reported in human mammary cell cancer biopsy samples107. Notably, a flow cytometry study of cells from ovarian cancer patients revealed that tumor cell proliferation, as determined by the percentage of cells in the S (DNA synthesis) phase, exhibits a highly significant 24-hour rhythm, with a peak in the mid-to-late morning that is nearly 12 h out of phase with nontumor cell proliferation in normal tissues108 (Fig. 5a, b). Along these lines, preclinical and clinical cancer studies reporting on the chronoutility of cell cycle phase-specific drugs, such as cisplatin or 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) (S phase-specific), docetaxel (M phase-specific), and seliciclib (G1 phase-specific), showed that their maximal efficacy and minimal toxicity were achieved at different times during the day109. Furthermore, palbociclib (PD-0332991), a selective inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 4/6, which is responsible for G1/S cell cycle progression, was found to reduce the growth of cultured cells and mouse tumors in a time-of-day-specific manner3. Together, these findings argue for chemotherapy approaches that are timed to coincide with times of high tumor cell vulnerability and low toxicity to normal tissues108 (Fig. 5).

Increasing evidence suggests direct roles for circadian clock genes in modulating the efficacy of anticancer therapies depending on the time of day. In recent individual chronopharmacological studies, the DNA alkylator temozolomide and irinotecan, a topoisomerase I inhibitor, was shown to exhibit rhythmic drug toxicity in GBM and colorectal cancer cells, respectively, with maximum drug sensitivity occurring near the peak of BMAL1 expression. These cytotoxic rhythms were ablated when BMAL1 was silenced110,111. These studies coincide with other reports indicating that elevated BMAL1 expression increases the sensitivity of colorectal cancer and TSCC cells to oxaliplatin and paclitaxel28,112. Similar to BMAL1, a recent mouse tumor graft study with human oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) cells suggested that PER2 is an effective chronomodulator of DNA damaging agents (e.g., oxaliplatin) since the efficacies of these drugs can be greatly boosted with timely administration at the peak of PER2 expression113. In further molecular analyses, PER2 was shown to periodically suppress proliferating cell nuclear antigen transcription, which, in turn, impeded the drug-induced DNA repair mechanism, thus increasing chronodrug sensitivity113. In addition, other individual studies using in vitro or in vivo tumor graft models showed that synthetic (e.g., SR9009, bortezomib, and aldehyde dehydrogenase inhibitor) and natural (e.g., curcumin) compounds could exert time-of-day-dependent antitumor activity via multiple circadian-dependent metabolic factors in GBM, liver, and breast cancer cells86,114,115. In line with these findings, a recent large-scale chronopharmacological analysis revealed that multiple anticancer drugs, including HSP90 inhibitors, exhibit time-of-day cytotoxicity, which requires cell cycle rhythms; however, these effects were abrogated in clock-deficient cancer cells116. In further analyses, Bmal1 ablation was shown to critically affect melanoma proliferation and time-of-day sensitivity to an HSP90 inhibitor in vivo116. Overall, these results clearly suggest that circadian regulation of cellular dynamics in tumors can dictate the time-of-day specificity of anticancer drugs (Fig. 5c).

Notably, it is increasingly recognized that chronotype, sex, age, disease status, and other interpersonal differences in rhythm status can largely affect pharmacodynamic variability among cancer patients, posing a daunting challenge in cancer drug therapy2. In particular, growing numbers of experimental and clinical studies suggest that environmental or physiological perturbations of circadian rhythms, such as shift work, abnormal sleep timing, irregular psychosociological stresses, and critical illness, can underlie interindividual variability in both cancer growth and response to cancer therapy3,117. Circadian disruption may also be related to the chronic sleep loss and depression suffered by many cancer patients following diagnosis and treatment118. Thus, it can be anticipated that training or enhancing the body clock with scheduled light exposure, mealtimes, or exercise, alongside a carefully timed chemotherapy regimen, would improve antitumor treatment.

Concluding remarks

In recent decades, extensive chronobiological research has expanded our understanding of the functional roles and mechanisms of the circadian clockwork in human health and diseases, including cancer. Circadian disruptions negatively influence both tumor molecular clocks and host circadian systems to increase cancer risk and progression. On the other hand, given the close link between cancers and other rhythm-disruptive pathologies, such as aging, obesity, and diabetes, enhancing circadian rhythms with chronophysiological interventions (e.g., chronophototherapy, chronodiet, and chronoexercise) is expected to highly benefit overall circadian health and cancer therapy. In addition, the dose timing of chemotherapeutic agents is an important therapeutic option that can improve tumor-specific cytotoxicity while sparing normal cells and host tissues. With the growing development of chronotherapeutic tools and strategies, it may be reasonable to expect that integrative chronotherapy will further improve the prevention and treatment of cancer.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Elson S. Floyd College of Medicine to Y.L. We would like to thank Amy Sullivan, Ph.D. from Obrizus Communications for assisting with the helpful editing of this article.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Koronowski KB, Sassone-Corsi P. Communicating clocks shape circadian homeostasis. Science. 2021;371:eabd0951. doi: 10.1126/science.abd0951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pariollaud M, Lamia KA. Cancer in the fourth dimension: what is the impact of circadian disruption? Cancer Discov. 2020;10:1455–1464. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee Y, et al. G1/S cell cycle regulators mediate effects of circadian dysregulation on tumor growth and provide targets for timed anticancer treatment. PLoS Biol. 2019;17:e3000228. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Papagiannakopoulos T, et al. Circadian rhythm disruption promotes lung tumorigenesis. Cell Metab. 2016;24:324–331. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hadadi E, et al. Chronic circadian disruption modulates breast cancer stemness and immune microenvironment to drive metastasis in mice. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:3193. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16890-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aiello I, et al. Circadian disruption promotes tumor-immune microenvironment remodeling favoring tumor cell proliferation. Sci. Adv. 2020;6:eaaz4530. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz4530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sulli G, Lam MTY, Panda S. Interplay between circadian clock and cancer: new frontiers for cancer treatment. Trends Cancer. 2019;5:475–494. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2019.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaix A, Zarrinpar A, Panda S. The circadian coordination of cell biology. J. Cell Biol. 2016;215:15–25. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201603076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patke A, Young MW, Axelrod S. Molecular mechanisms and physiological importance of circadian rhythms. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020;21:67–84. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0179-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takahashi JS. Transcriptional architecture of the mammalian circadian clock. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2017;18:164–179. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anafi RC, et al. Machine learning helps identify CHRONO as a circadian clock component. PLoS Biol. 2014;12:e1001840. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee Y, et al. The NRON complex controls circadian clock function through regulated PER and CRY nuclear translocation. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:11883. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48341-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brancaccio M, et al. Cell-autonomous clock of astrocytes drives circadian behavior in mammals. Science. 2019;363:187–192. doi: 10.1126/science.aat4104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buijs RM, Guzman Ruiz MA, Mendez Hernandez R, Rodriguez Cortes B. The suprachiasmatic nucleus; a responsive clock regulating homeostasis by daily changing the setpoints of physiological parameters. Auton. Neurosci. 2019;218:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finger AM, Kramer A. Peripheral clocks tick independently of their master. Genes Dev. 2021;35:304–306. doi: 10.1101/gad.348305.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Drunen R, Eckel-Mahan K. Circadian rhythms of the hypothalamus: from function to physiology. Clocks Sleep. 2021;3:189–226. doi: 10.3390/clockssleep3010012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gabriel BM, Zierath JR. Circadian rhythms and exercise—resetting the clock in metabolic disease. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019;15:197–206. doi: 10.1038/s41574-018-0150-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reinke H, Asher G. Crosstalk between metabolism and circadian clocks. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019;20:227–241. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scheiermann C, Gibbs J, Ince L, Loudon A. Clocking in to immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018;18:423–437. doi: 10.1038/s41577-018-0008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brum MCB, et al. Night shift work, short sleep and obesity. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2020;12:13. doi: 10.1186/s13098-020-0524-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.IARC Monographs Vol 124 group. Carcinogenicity of night shift work. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:1058–1059. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30455-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Filipski E, Lévi F. Circadian disruption in experimental cancer processes. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2009;8:298–302. doi: 10.1177/1534735409352085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Logan RW, et al. Chronic shift-lag alters the circadian clock of NK cells and promotes lung cancer growth in rats. J. Immunol. 2012;188:2583–2591. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taniguchi H, et al. Epigenetic inactivation of the circadian clock gene BMAL1 in hematologic malignancies. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8447–8454. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y, et al. BMAL1 knockdown triggers different colon carcinoma cell fates by altering the delicate equilibrium between AKT/mTOR and P53/P21 pathways. Aging. 2020;12:8067–8083. doi: 10.18632/aging.103124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang W, et al. The circadian clock gene Bmal1 acts as a potential anti-oncogene in pancreatic cancer by activating the p53 tumor suppressor pathway. Cancer Lett. 2016;371:314–325. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang Q, et al. Circadian clock gene Bmal1 inhibits tumorigenesis and increases paclitaxel sensitivity in tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2017;77:532–544. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korkmaz T, et al. Opposite carcinogenic effects of circadian clock gene BMAL1. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:16023. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34433-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fekry B, et al. Incompatibility of the circadian protein BMAL1 and HNF4alpha in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:4349. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06648-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peng H, et al. ARNTL hypermethylation promotes tumorigenesis and inhibits cisplatin sensitivity by activating CDK5 transcription in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;38:11. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0997-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gwon DH, et al. BMAL1 suppresses proliferation, migration, and invasion of U87MG cells by downregulating cyclin B1, phospho-AKT, and metalloproteinase-9. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:2352. doi: 10.3390/ijms21072352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sakamoto W, Takenoshita S. Overexpression of both clock and Bmal1 inhibits entry to S phase in human colon cancer cells. Fukushima J. Med. Sci. 2015;61:111–124. doi: 10.5387/fms.2015-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hua H, et al. Circadian gene mPer2 overexpression induces cancer cell apoptosis. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:589–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00225.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oda A, et al. Clock gene mouse period2 overexpression inhibits growth of human pancreatic cancer cells and has synergistic effect with cisplatin. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:1201–1209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanoun M, et al. Epigenetic silencing of the circadian clock gene CRY1 is associated with an indolent clinical course in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. PloS ONE. 2012;7:e34347. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun CM, et al. Per2 inhibits k562 leukemia cell growth in vitro and in vivo through cell cycle arrest and apoptosis induction. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2010;16:403–411. doi: 10.1007/s12253-009-9227-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhanfeng N, et al. Period2 downregulation inhibits glioma cell apoptosis by activating the MDM2-TP53 pathway. Oncotarget. 2016;7:27350–27362. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Z, Li F, Wei M, Zhang S, Wang T. Circadian clock protein PERIOD2 suppresses the PI3K/Akt pathway and promotes cisplatin sensitivity in ovarian cancer. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020;12:11897–11908. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S278903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gong X, Tang H, Yang K. PER1 suppresses glycolysis and cell proliferation in oral squamous cell carcinoma via the PER1/RACK1/PI3K signaling complex. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12:276. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-03563-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nirvani M, Khuu C, Utheim TP, Sand LP, Sehic A. Circadian clock and oral cancer. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2018;8:219–226. doi: 10.3892/mco.2017.1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chan AB, Huber AL, Lamia KA. Cryptochromes modulate E2F family transcription factors. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:4077. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-61087-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ye Y, et al. The genomic landscape and pharmacogenomic interactions of clock genes in cancer chronotherapy. Cell Syst. 2018;6:314–328. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2018.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Louw A, Badiei A, Creaney J, Chai MS, Lee YCG. Advances in pathological diagnosis of mesothelioma: what pulmonologists should know. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2019;25:354–361. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dong Z, et al. Targeting glioblastoma stem cells through disruption of the circadian clock. Cancer Discov. 2019;9:1556–1573. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Puram RV, et al. Core circadian clock genes regulate leukemia stem cells in AML. Cell. 2016;165:303–316. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang J, et al. Circadian protein BMAL1 promotes breast cancer cell invasion and metastasis by upregulating matrix metalloproteinase9 expression. Cancer Cell Int. 2019;19:182. doi: 10.1186/s12935-019-0902-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shafi AA, et al. The circadian cryptochrome, CRY1, is a pro-tumorigenic factor that rhythmically modulates DNA repair. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:401. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20513-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee JH, Gaddameedhi S, Ozturk N, Ye R, Sancar A. DNA damage-specific control of cell death by cryptochrome in p53-mutant ras-transformed cells. Cancer Res. 2013;73:785–791. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jia M, et al. Circadian clock protein CRY1 prevents paclitaxelinduced senescence of bladder cancer cells by promoting p53 degradation. Oncol. Rep. 2021;45:1033–1043. doi: 10.3892/or.2020.7914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sulli G, Manoogian ENC, Taub PR, Panda S. Training the circadian clock, clocking the drugs, and drugging the clock to prevent, manage, and treat chronic diseases. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2018;39:812–827. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2018.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vallee A, Lecarpentier Y, Guillevin R, Vallee JN. The influence of circadian rhythms and aerobic glycolysis in autism spectrum disorder. Transl. Psychiatry. 2020;10:400. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-01086-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mao L, et al. Circadian gating of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer cells via melatonin-regulation of GSK3beta. Mol. Endocrinol. 2012;26:1808–1820. doi: 10.1210/me.2012-1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dauchy RT, et al. Effect of daytime blue-enriched LED light on the nighttime circadian melatonin inhibition of hepatoma 7288CTC Warburg effect and progression. Comp. Med. 2018;68:269–279. doi: 10.30802/AALAS-CM-17-000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dauchy RT, et al. Circadian and melatonin disruption by exposure to light at night drives intrinsic resistance to tamoxifen therapy in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2014;74:4099–4110. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xiang S, et al. Doxorubicin resistance in breast cancer is driven by light at night-induced disruption of the circadian melatonin signal. J. Pineal Res. 2015;59:60–69. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cuesta M, Boudreau P, Cermakian N, Boivin DB. Rapid resetting of human peripheral clocks by phototherapy during simulated night shift work. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:16310. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16429-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kervezee L, Cuesta M, Cermakian N, Boivin DB. The Phase-Shifting Effect of Bright Light Exposure on Circadian Rhythmicity in the Human Transcriptome. J. Biol. Rhythms. 2019;34:84–97. doi: 10.1177/0748730418821776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lundell LS, et al. Time-restricted feeding alters lipid and amino acid metabolite rhythmicity without perturbing clock gene expression. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:4643. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18412-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liang Y, et al. Calorie restriction is the most reasonable anti-aging intervention: a meta-analysis of survival curves. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:5779. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-24146-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alidadi M, et al. The effect of caloric restriction and fasting on cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2020;73:30–44. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2020.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brandhorst S, Longo VD. Fasting and caloric restriction in cancer prevention and treatment. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2016;207:241–266. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-42118-6_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhao X, et al. The role and its mechanism of intermittent fasting in tumors: friend or foe? Cancer Biol. Med. 2021;18:63–73. doi: 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2020.0250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Christensen JF, Simonsen C, Hojman P. Exercise training in cancer control and treatment. Compr. Physiol. 2018;9:165–205. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c180016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weitzer J, et al. Effect of time of day of recreational and household physical activity on prostate and breast cancer risk (MCC-Spain study) Int. J. Cancer. 2021;148:1360–1371. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Najafi M, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with melatonin for targeting human cancers: a review. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019;234:2356–2372. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang YM, et al. The efficacy and safety of melatonin in concurrent chemotherapy or radiotherapy for solid tumors: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2012;69:1213–1220. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-1828-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rodriguez-Garcia A, et al. Phenotypic changes caused by melatonin increased sensitivity of prostate cancer cells to cytokine-induced apoptosis. J. Pineal Res. 2013;54:33–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2012.01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lissoni P. Biochemotherapy with standard chemotherapies plus the pineal hormone melatonin in the treatment of advanced solid neoplasms. Pathol. Biol. 2007;55:201–204. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2006.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shimba A, Ikuta K. Glucocorticoids regulate circadian rhythm of innate and adaptive immunity. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:2143. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.02143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cook AM, McDonnell AM, Lake RA, Nowak AK. Dexamethasone comedication in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy causes substantial immunomodulatory effects with implications for chemo-immunotherapy strategies. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5:e1066062. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1066062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pufall MA. Glucocorticoids and cancer. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2015;872:315–333. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2895-8_14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kiessling S, et al. Enhancing circadian clock function in cancer cells inhibits tumor growth. BMC Biol. 2017;15:13. doi: 10.1186/s12915-017-0349-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cash E, et al. The role of the circadian clock in cancer hallmark acquisition and immune-based cancer therapeutics. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021;40:119. doi: 10.1186/s13046-021-01919-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ribeiro RFN, Cavadas C, Silva MMC. Small-molecule modulators of the circadian clock: pharmacological potentials in circadian-related diseases. Drug Discov. Today. 2021;26:1620–1641. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2021.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Narasimamurthy R, Virshup DM. The phosphorylation switch that regulates ticking of the circadian clock. Mol. Cell. 2021;81:1133–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Di Maira G, et al. The protein kinase CK2 contributes to the malignant phenotype of cholangiocarcinoma cells. Oncogenesis. 2019;8:61. doi: 10.1038/s41389-019-0171-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Monastyrskyi A, et al. Development of dual casein kinase 1delta/1epsilon (CK1delta/epsilon) inhibitors for treatment of breast cancer. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018;26:590–602. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2017.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liu M, et al. IC261, a specific inhibitor of CK1delta/epsilon, promotes aerobic glycolysis through p53-dependent mechanisms in colon cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020;16:882–892. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.40960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Oshima T, et al. Cell-based screen identifies a new potent and highly selective CK2 inhibitor for modulation of circadian rhythms and cancer cell growth. Sci. Adv. 2019;5:eaau9060. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aau9060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gowda C, et al. Casein Kinase II (CK2) as a therapeutic target for hematological malignancies. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2017;23:95–107. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666161006154311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Janovska P, Normant E, Miskin H, Bryja V. Targeting casein kinase 1 (CK1) in hematological cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:9026. doi: 10.3390/ijms21239026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Banerjee S, et al. Pharmacological targeting of the mammalian clock regulates sleep architecture and emotional behavior. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5759. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.De Mei C, et al. Dual inhibition of REV-ERBbeta and autophagy as a novel pharmacological approach to induce cytotoxicity in cancer cells. Oncogene. 2015;34:2597–2608. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sulli G, et al. Pharmacological activation of REV-ERBs is lethal in cancer and oncogene-induced senescence. Nature. 2018;553:351–355. doi: 10.1038/nature25170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wagner PM, Monjes NM, Guido ME. Chemotherapeutic effect of SR9009, a REV-ERB agonist, on the human glioblastoma T98G cells. ASN Neuro. 2019;11:1759091419892713. doi: 10.1177/1759091419892713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shen W, et al. SR9009 induces a REV-ERB dependent anti-small-cell lung cancer effect through inhibition of autophagy. Theranostics. 2020;10:4466–4480. doi: 10.7150/thno.42478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang J, et al. ROR-gamma drives androgen receptor expression and represents a therapeutic target in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nat. Med. 2016;22:488–496. doi: 10.1038/nm.4070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lytle NK, et al. A multiscale map of the stem cell state in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cell. 2019;177:572–586. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cai D, et al. RORgamma is a targetable master regulator of cholesterol biosynthesis in a cancer subtype. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:4621. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12529-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hu X, et al. Synthetic RORgamma agonists regulate multiple pathways to enhance antitumor immunity. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5:e1254854. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1254854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ashrafizadeh M, et al. Nobiletin in cancer therapy: how this plant derived-natural compound targets various oncogene and onco-suppressor pathways. Biomedicines. 2020;8:100. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines8050100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hirota T, et al. Identification of small molecule activators of cryptochrome. Science. 2012;337:1094–1097. doi: 10.1126/science.1223710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lin HH, Robertson KL, Bisbee HA, Farkas ME. Oncogenic and circadian effects of small molecules directly and indirectly targeting the core circadian clock. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2020;19:1534735420924094. doi: 10.1177/1534735420924094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chun SK, et al. A synthetic cryptochrome inhibitor induces anti-proliferative effects and increases chemosensitivity in human breast cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015;467:441–446. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.09.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dallmann R, Okyar A, Lévi F. Dosing-time makes the poison: circadian regulation and pharmacotherapy. Trends Mol. Med. 2016;22:430–445. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Innominato PF, et al. The circadian timing system in clinical oncology. Ann. Med. 2014;46:191–207. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2014.916990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hrushesky WJ. Circadian timing of cancer chemotherapy. Science. 1985;228:73–75. doi: 10.1126/science.3883493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lévi F, et al. Chemotherapy of advanced ovarian cancer with 4’-O-tetrahydropyranyl doxorubicin and cisplatin: a randomized phase II trial with an evaluation of circadian timing and dose-intensity. J. Clin. Oncol. 1990;8:705–714. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.4.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Innominato PF, et al. Efficacy and safety of chronomodulated irinotecan, oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin combination as first- or second-line treatment against metastatic colorectal cancer: Results from the International EORTC 05011 Trial. Int. J. Cancer. 2020;148:2512–2521. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Altinok A, Lévi F, Goldbeter A. Identifying mechanisms of chronotolerance and chronoefficacy for the anticancer drugs 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatin by computational modeling. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009;36:20–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2008.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pullarkat ST, et al. Thymidylate synthase gene polymorphism determines response and toxicity of 5-FU chemotherapy. Pharmacogenomics J. 2001;1:65–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Harris BE, Song R, Soong SJ, Diasio RB. Relationship between dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase activity and plasma 5-fluorouracil levels with evidence for circadian variation of enzyme activity and plasma drug levels in cancer patients receiving 5-fluorouracil by protracted continuous infusion. Cancer Res. 1990;50:197–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Jacobs BA, et al. Pronounced between-subject and circadian variability in thymidylate synthase and dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase enzyme activity in human volunteers. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016;82:706–716. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zeng ZL, et al. Circadian rhythm in dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase activity and reduced glutathione content in peripheral blood of nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. Chronobiol. Int. 2005;22:741–754. doi: 10.1080/07420520500179969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gou XX, et al. Induction chronomodulated chemotherapy plus radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a Phase II prospective randomized study. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2018;14:1613–1619. doi: 10.4103/jcrt.JCRT_883_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Garcia-Sainz M, Halberg F. Mitotic rhythms in human cancer, reevaluated by electronic computer programs. Evidence for chronopathology. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 1966;37:279–292. doi: 10.1093/jnci/37.3.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Klevecz RR, Shymko RM, Blumenfeld D, Braly PS. Circadian gating of S phase in human ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 1987;47:6267–6271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bernard S, Cajavec Bernard B, Lévi F, Herzel H. Tumor growth rate determines the timing of optimal chronomodulated treatment schedules. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2010;6:e1000712. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Dulong S, Ballesta A, Okyar A, Lévi F. Identification of circadian determinants of cancer chronotherapy through in vitro chronopharmacology and mathematical modeling. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2015;14:2154–2164. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Slat EA, et al. Cell-intrinsic, Bmal1-dependent circadian regulation of temozolomide sensitivity in glioblastoma. J. Biol. Rhythms. 2017;32:121–129. doi: 10.1177/0748730417696788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zeng ZL, et al. Overexpression of the circadian clock gene Bmal1 increases sensitivity to oxaliplatin in colorectal cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014;20:1042–1052. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Tang Q, et al. Periodic oxaliplatin administration in synergy with PER2-mediated PCNA transcription repression promotes chronochemotherapeutic efficacy of OSCC. Adv. Sci. 2019;6:1900667. doi: 10.1002/advs.201900667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Matsunaga N, et al. Optimized dosing schedule based on circadian dynamics of mouse breast cancer stem cells improves the antitumor effects of aldehyde dehydrogenase inhibitor. Cancer Res. 2018;78:3698–3708. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-4034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sarma A, et al. The circadian clock modulates anticancer properties of curcumin. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:759. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2789-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lee Y, et al. Time-of-day specificity of anticancer drugs may be mediated by circadian regulation of the cell cycle. Sci. Adv. 2021;7:eabd2645. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abd2645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Walker WH, 2nd, et al. Light pollution and cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:9360. doi: 10.3390/ijms21249360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Telias I, Wilcox ME. Sleep and circadian rhythm in critical illness. Crit. Care. 2019;23:82. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2366-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]