Abstract

In mammals, molecular mechanisms and factors involved in the tight regulation of telomerase expression and activity are still largely undefined. In this study, we provide evidence for a role of estrogens and their receptors in the transcriptional regulation of hTERT, the catalytic subunit of human telomerase and, consequently, in the activation of the enzyme. Through a computer analysis of the hTERT 5′-flanking sequences, we identified a putative estrogen response element (ERE) which was capable of binding in vitro human estrogen receptor α (ERα). In vivo DNA footprinting revealed specific modifications of the ERE region in ERα-positive but not ERα-negative cells upon treatment with 17β-estradiol (E2), indicative of estrogen-dependent chromatin remodelling. In the presence of E2, transient expression of ERα but not ERβ remarkably increased hTERT promoter activity, and mutation of the ERE significantly reduced this effect. No telomerase activity was detected in human ovary epithelial cells grown in the absence of E2, but the addition of the hormone induced the enzyme within 3 h of treatment. The expression of hTERT mRNA and protein was induced in parallel with enzymatic activity. This prompt estrogen modulation of telomerase activity substantiates estrogen-dependent transcriptional regulation of the hTERT gene. The identification of hTERT as a target of estrogens represents a novel finding which advances the understanding of telomerase regulation in hormone-dependent cells and has implications for a potential role of hormones in their senescence and malignant conversion.

Most human somatic cells do not express telomerase, the ribonucleoprotein that elongates telomeric DNA, or its catalytic protein, hTERT, which is limiting for enzyme activity (33). In humans, telomerase is regulated in a tissue-specific manner during development (42); the enzyme is present in early embryogenesis but is repressed upon cell differentiation in somatic tissues (27, 42). Loss of enzymatic activity is accompanied by loss of the full-length transcript of hTERT and/or by the appearance of alternatively spliced transcripts that are unlikely to encode functional proteins (21, 42). In the adult, telomerase persists only in germ line cells and in progenitor cells of somatic tissues with self-renewing potential, in agreement with the requirement for the enzyme for sustained cell proliferation (16). How hTERT silencing is achieved and which factors contribute to this process are presently unknown, although the regulation of hTERT expression appears to be primarily at the transcriptional level (42). An understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation of telomerase activity might allow the modulation of telomerase expression and, consequently, of cell life span (4, 43), with important potential therapeutic applications in aging and malignancy.

Several lines of evidence suggest that sex steroid hormones may be good candidates as physiological regulators of hTERT expression. Recent findings are consistent with the hypothesis that telomerase activity is potentially under hormonal control in some estrogen-targeted tissues, such as the endometrium (25, 37, 40), and the prostate (30), and in epithelial cells with high renewing potential from estrogen-regulated tissues (3). Physiological responses to estrogen are mediated, within specific tissues, by at least two members of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily, the estrogen receptors (ERs) ERα and ERβ (2). These are ligand-dependent transcription factors belonging to a large family of structurally related proteins that are able to modulate the expression of a variety of genes involved in diverse biological functions, such as cell proliferation, morphogenesis, cellular differentiation, and programmed cell death. ERs act by direct interaction of the hormone-receptor complex with a set of specific DNA sequences, the estrogen response elements (EREs), localized in the 5′-flanking regions of hormone-regulated genes. Distinct ligand-directed conformational changes of the hormone-receptor complex may result, in turn, in transcriptional silencing or activation of target genes (2, 28). Alternative mechanisms of ER activation, involving coregulatory proteins (19, 20), transcription factors such as AP-1 or Sp1 (35, 44), and/or phosphorylation signaling pathways, have also been reported (2).

The recent cloning and characterization of the hTERT gene and its promoter region (6, 17, 40, 45) has provided essential reagents for the investigation of the molecular mechanisms involved in the regulation of telomerase in different cell backgrounds. In this study, we provide evidence for a potential role of estrogens and ERs in the transcriptional regulation of hTERT by demonstrating that a noncanonical ERE within the hTERT promoter is functional in vitro and in vivo and that the addition of estrogen to human ovary epithelium cell cultures results in the induction of hTERT expression and of telomerase activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

Human ovarian surface epithelium (HOSE) cell strains GRO, LLO, and LEA and immortal HOSE cell line WOO were cultured in E3 medium with 3% fetal calf serum (FCS) (8). The human ovarian cancer cell line OVCA-433 (36) was grown in RPMI 1640 with 10% FCS, while cervical cancer HeLa cells, breast cancer MCF-7 and MDA-MB231 cells, and mouse NIH 3T3 fibroblasts were grown in Dulbecco modified essential medium with 10% FCS. Forty-eight hours prior to experimental use, the cells were switched to medium supplemented with hormone-deprived serum (18).

Plasmids and transfections.

Plasmids P-1009 and P-330 and the pGL2-Enhancer vector have been described previously (6). P-1009Mut, with a mutated ERE, was generated using a QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) and the following oligonucleotide sequence: 5′-CCTCCCCCTTGTGCGGGCATGATGTGATCAGATGTTGGCC-3′.

The hTERT-ERE-TK reporter was generated by inserting double-stranded oligonucleotides encompassing the hTERT promoter (−956 to −930) into the linker region of pBLCAT2 (12) upstream of the thymidine kinase (TK) promoter at bp −105. All constructs were sequenced using the dideoxynucleotide method (38). pSG5-HEO, encoding human ERα (13), and the human ERβ expression vector (24) were gifts from P. Chambon (Strasbourg, France) and J. A. Gustafsson (Huddinge, Sweden), respectively. The reporter vector for the Xenopus laevis vitellogenin B1 (VIT) promoter has been previously described (12). pCMV-β-gal was used as an internal control to monitor transfection efficiency. Cells were electroporated as described previously (12) and assayed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activities using reagents and protocols from Promega (Madison, Wis.).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay.

A 32P-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotide containing the hTERT ERE (5′-GCATGTGTGTGCGGGCGGGATGTGACCAGATGTGATCC-3′; bp −949 to −935 upstream of the ATG) was assayed for binding to extracts from Spodoptera frugiperda Sf9 cells infected with a baculovirus expressing human ERα (5) or ERβ (Alexis Biochemicals, Milan, Italy) or with a control baculovirus. As a control for ER binding, a 32P-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotide spanning the canonical X. laevis VIT ERE was used. Competition experiments were performed by adding to the binding mixture increasing amounts of unlabeled oligonucleotides containing the hTERT ERE, the human coaggulation factor XII ERE (12), or the mutant hTERT ERE 20 min prior to the addition of the 32P-labeled probe. Supershift experiments with ERβ were carried out with anti-ERβ antibody L-20X (Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, Calif.). Binding reactions and native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis were carried out as previously described (12).

Western blot analysis.

For detection of ERα expression, cell lysates were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). Immunostaining of proteins was done with antibody HC-20 according to supplier instructions (Santa Cruz), and detection was done by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Corp., Arlington Heights, Ill.).

Genomic footprinting.

Cells were treated with the DNA-alkylating reagent dimethyl sulfate (DMS) (0.1% for 2 min for MCF-7, MDA-MB231, and HeLa cells and 0.2% for 4 min for OVCA-433 cells), and their DNA was cleaved with piperidine. Genomic footprinting was performed by ligation-mediated (LM) PCR (9) with Vent DNA polymerase for first-strand extension and subsequent PCR amplification. To generate footprints for the endogenous hTERT gene, the following primers, specific for the region of interest, were used (coding strand): primer 1, GAATCGGCCTAGGCTGTG; primer 2, ACCGGGCGCCTCACACCAGCC; and primer 3, ACCGGGCGCCTCACACCAGCCACAACGG. Labeled PCR products were resolved on a 6% polyacrylamide–8 M urea sequencing gel. Control samples consisted of chromatin-free DNA from each cell line treated in vitro with 0.125% DMS for 2 min. Volumetric integration of signal intensities was performed with NIH Image software (version 1.58), and quantitation was done as described by Dey et al. (9). Briefly, the average value of each band from three independent experiments was normalized to the value of the corresponding band in the control guanine ladder. Methylation percentages were obtained by normalization of values for ERα-positive (MCF-7 and OVCA-433) cells to those for ERα-negative (MDA-MB231 and HeLa) cells, which showed no protection or hypersensitivity. Values of <15% were considered not significant (32).

RT-PCR analysis of hTERT mRNA.

Expression of hTERT mRNA was analyzed by semiquantitative reverse transcription (RT)-PCR amplification. Total RNA was prepared from HOSE cells using RNAzol B (Biotech, Rome, Italy) according to the manufacturer's protocol. One microgram of total RNA was reverse transcribed at 37°C for 45 min in the presence of random hexamers and Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Gibco-BRL). hTERT mRNA analysis was carried out by PCR amplification of a fragment of 145 bp using primers and conditions described by Ulaner et al. (42). The housekeeping aldolase mRNA, used as an external standard, was amplified from the same cDNA reaction mixture using specific primers (31). The exponential phase of amplification was previously determined by serial dilution of RT reaction mixtures for each cDNA template used and PCR performed under these conditions. Amplified PCR products were electrophoresed on a 3% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml) and visualized under UV light.

Immunofluorescence.

LEA and LLO cells, grown in E3 medium with hormone-deprived serum, were seeded in 35-mm plates. After 16 h, the medium was replaced with fresh medium containing 17β-estradiol (E2) at a final concentration of 10−7 M or the equivalent volume of vehicle alone. Cells were immunostained with the telomerase-specific antibody K-370 as described by Martin-Rivera et al. (29), and nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33258. Images were captured with a Zeiss fluorescence microscope.

Telomerase assay.

Extracts from GRO, LEA, LLO, and WOO cells were prepared by detergent lysis, and enzymatic activity was detected by the PCR-based telomere repeat amplification protocol (TRAP) (22).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Ligand-dependent occupancy of the hTERT promoter in vitro and in vivo.

A computer-assisted analysis of the hTERT 5′-flanking sequence (6) revealed a composite regulatory unit comprising an imperfect palindromic consensus sequence for the ERE (5′-GGCGGGATGTGACCA-3′, at positions −949 to −935 relative to the ATG), partially overlapping an AP1 binding site and adjacent to an SP1 motif (Fig. 1a).

FIG. 1.

(a) Schematic diagram and nucleotide sequence of the hTERT gene 5′-flanking sequences. The region extending to bp 1009 upstream of the hTERT ATG (+1) and the locations of the two ERE half-sites and of an additional downstream half-site (black triangles) are indicated. The hTERT promoter sequence between bp −1009 and −755 is shown below the diagram. The boxes define the composite regulatory unit comprising an imperfect palindromic ERE at positions −949 to −935, a partially overlapping AP1 binding site, an adjacent SP1 motif, and the single ERE half-site at positions −794 to −789. The asterisks indicate G residues altered in the genomic footprints shown in Fig. 2. (b) ERα binding to the hTERT ERE. A 32P-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotide containing the hTERT ERE sequence was incubated with extracts of Sf9 cells infected with wild-type (wt) baculovirus (lane 2) or recombinant baculovirus expressing human ERα (lanes 3 to 10). Lane 1, probe alone; lane 3, recombinant ERα alone; lanes 4 to 9, like lane 3 but with 25-, 100-, and 250-fold molar excesses of unlabeled oligonucleotides containing the hTERT (lanes 4 to 6) or FXII (lanes 7 to 9) ERE sequences; lane 10, like lane 3 but with a 250-fold molar excess of an unrelated unlabeled oligonucleotide (NS). (c) ERβ binding to EREs. 32P-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotides containing the VIT ERE (lanes 1 to 4) or the hTERT ERE (lanes 5 to 8) were incubated with extracts of Sf9 cells infected with recombinant baculovirus expressing human ERβ (lanes 2 to 4 and 6 to 8) in the presence of (E2) (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8) or of TAM (lanes 3 and 7). Anti-ERβ antibodies (lanes 4 and 8) were used for supershifting ERβ-ERE complexes. Lane 1, VIT ERE probe alone; lane 5, hTERT ERE probe alone.

We first evaluated the ability of the hTERT promoter to bind in vitro ligand-activated human ERs. Incubation of a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide spanning the hTERT ERE with extracts from S. frugiperda (Sf9) cells infected with a baculovirus expressing ERα (Fig. 1b, lane 3) resulted in the formation of a specific complex that was progressively inhibited by increasing concentrations of unlabeled oligonucleotides corresponding to the hTERT ERE (Fig. 1b, lanes 4 to 6) or to the well-characterized FXII ERE (12) (Fig. 1b, lanes 7 to 9). Compared to the hTERT ERE, the FXII ERE was a less efficient competitor, likely because of sequence divergence between the two oligonucleotides within the 5′ half-site. No inhibition was observed upon the addition of a 250-fold molar excess of an unrelated oligonucleotide (Fig. 1b, lane 10), and no complex was formed when the hTERT ERE was incubated with extracts from SF9 cells infected with wild-type virus (Fig. 1b, lane 2), underscoring the specificity of the interaction between ERα and the hTERT ERE. An oligonucleotide containing a mutated hTERT ERE competed weakly for ER binding (data not shown), in agreement with functional data showing that mutations strongly reduced the estrogen response of the element (see Fig. 3a and b). Incubation of 32P-labeled hTERT ERE with Sf9 cells infected with a baculovirus expressing ERβ did not show any interaction, whether in the presence or absence of E2 or of the antiestrogen 4-hydroxytamoxifen (TAM). As a control for the functionality of ERβ, the canonical X. laevis VIT ERE was used (Fig. 1c). In the presence of E2, ERβ bound the VIT ERE and was supershifted upon the addition of anti-ERβ antibody (Fig. 1c, lanes 2 and 4, respectively). The addition of TAM to the binding mixture inhibited the formation of the ERβ-VIT ERE complex (Fig. 1c, lane 3).

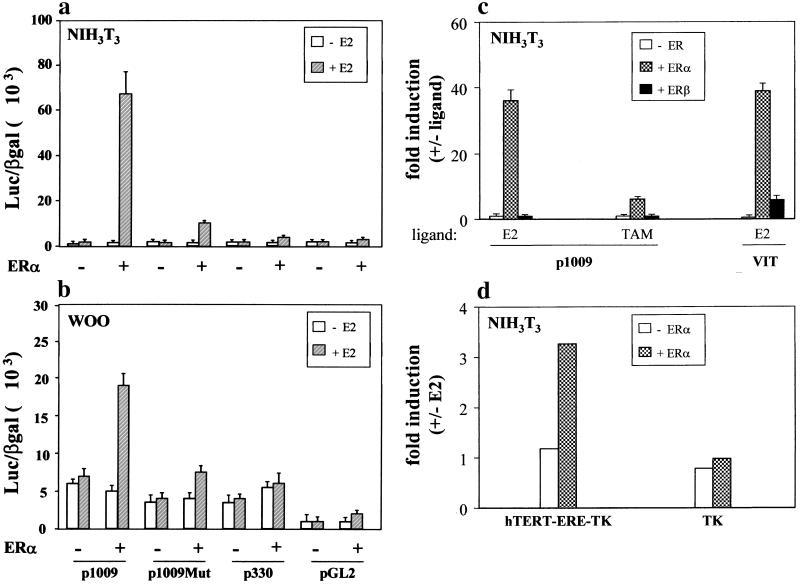

FIG. 3.

Effects of E2 and ERs on hTERT promoter activity. (a and b) NIH 3T3 or WOO cells, grown in the presence or absence of 10−7 M E2, were cotransfected with 5 μg of the hTERT promoter-luciferase reporter plasmids (P-1009, P-1009Mut, and P-330) or the control vector pGL2-Enhancer (pGL2), 5 μg of the ERα expression vector, and 250 ng of pCMV-βgal. Cells were assayed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activities after 48 to 72 h. Data are expressed as light units/β-galactosidase units in the presence (+) or absence (−) of hormone. Results represent the average (± standard error [SE]) of a minimum of three independent experiments, each performed in duplicate. (c) NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with P-1009, alone (− ER) or in combination with expression vectors for ERα (+ ERα) or ERβ (+ ERβ), in the presence of E2 or TAM. The VIT promoter (nucleotides −596 to +8), containing a perfect ERE, was used as a control reporter (VIT). Results represent the average (± SE) of three independent experiments, each performed in duplicate, and values are expressed as fold induction (ratio with and without ligand). (d) NIH 3T3 cells were cotransfected with (+ ERα) or without (− ERα) the expression vector for ERα and the hTERT-ERE-TK and TK reporters as indicated and cultured in the absence or presence of E2. Results of a representative experiment out of two, each performed in triplicate, are expressed as fold induction as described for panel c.

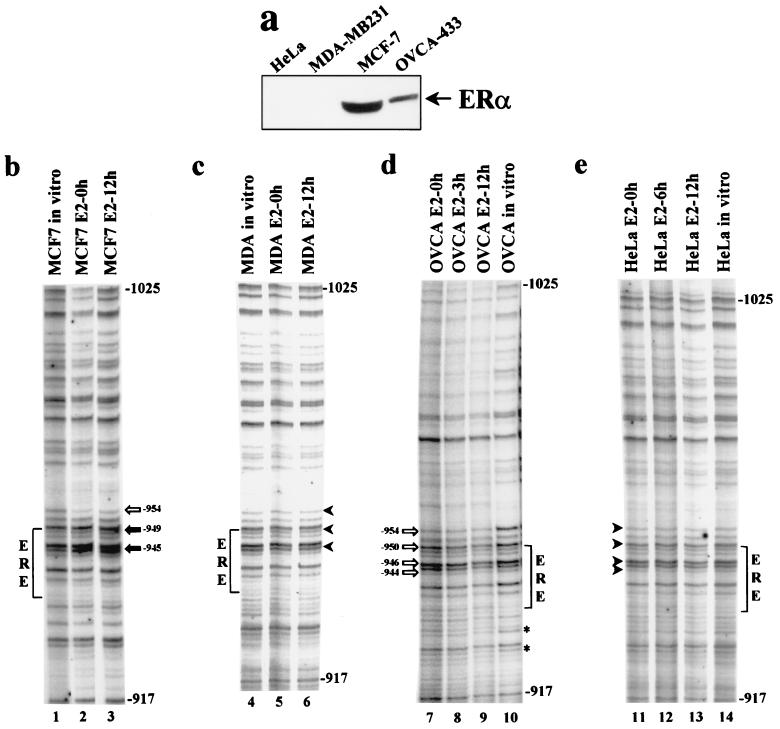

To assess the functionality of the hTERT ERE in cells from estrogen-regulated tissues, we compared the in vivo DNA footprints over this region in ERα-positive (MCF-7 and OVCA-433) and ERα-negative (MDA-MB231 and HeLa) cells (Fig. 2a) cultured in the presence or absence of E2 (10−7 M) for various times. Cells were treated with DMS, and their DNA was analyzed by LM PCR with primers specific for the region of the hTERT promoter from positions −1025 to −917 relative to the ATG (Fig. 1a). The extent of protection or hypersensitivity of specific residues was evaluated by densitometry (Table 1) (Materials and Methods). A comparison of DNA extracted from DMS-treated cells to purified DNA treated with DMS in vitro (Fig. 2b to e) revealed a mixed pattern of protected and hyperreactive G residues in cells constitutively expressing ERα (e.g., MCF-7 and OVCA-433). In particular, in MCF-7 cells grown in the absence of E2, we observed protection (∼70%) of the G at position −954; protection was less pronounced (∼40%) in cells grown with the hormone (Fig. 2b, compare lane 2 with lanes 1 and 3). The addition of estrogen resulted in hypermethylation (30 to 55%) of two clusters of G residues, at positions −949 to −945, immediately upstream of and within the hTERT ERE 5′ half-site; this result was compatible with unmasking of binding sites normally inaccessible to transcription factors, as suggested for the uteroglobin gene enhancer in hormone-treated endometrial cells (39). In OVCA-433 cells (Fig. 2d), estrogen treatment resulted in a different pattern, with consistent protection (35 to 45%) of four G residues (at positions −954, −950, −946, and −944) upstream of and within the 5′ half-site of the ERE. In addition, G residues at positions −931 and −927 downstream of the ERE were protected, in comparison to the results for in vitro-treated DNA or DNA from cells grown without estrogen. Protection of all these regions may be mediated by the conformational and functional changes that the ER undergoes following transition from an inactive to an active state (2, 28). The presence of a binding site for AP1 and SP1 adjacent to or within the ERE may also contribute to this effect, since these nuclear proteins have been shown to interact with ERα in certain contexts involving estrogen-regulated promoters (35, 44).

FIG. 2.

(a) Expression of endogenous ERα by Western blot analysis. ERα-negative (HeLa and MDA-MB231) and ERα-positive (OVCA-433 and MCF-7) cells were lysed directly in protein sample buffer, and equal amounts of protein were separated on a denaturing 12% polyacrylamide gel. Immunostaining was performed with anti-ERα antibody HC-20. As a loading control, proteins were stained with Ponceau S (data not shown). Treatment with E2 did not affect the levels of ERα in the ER-positive cells (data not shown). (b to e) DMS genomic footprinting of the hTERT promoter. Cells were treated with the DNA-alkylating reagent DMS, and their DNA was cleaved with piperidine and analyzed by LM PCR with primers specific for the region of the hTERT promoter from bp −1025 to −917 relative to the ATG (Fig. 1a). (b) Breast cancer MCF-7 cells. (c) Breast cancer MDA-MB231 cells. (d) Ovarian cancer OVCA-433 cells. (e) Cervical cancer HeLa cells. Length (in hours) of treatment with E2 (lanes 2, 3, 5 to 9, and 11 to 13) is indicated. In vitro-methylated DNA from each cell line is shown in lanes 1, 4, 10, and 14. Protected guanine residues over the ERE region are indicated by open arrows, while relevant hypermethylated guanine residues are indicated by filled arrows (b and d). Corresponding G residues unmodified in ERα-negative cells are indicated by arrowheads (c and e). The asterisks (in panel d) indicate two protected guanine residues, of unknown significance, downstream of the ERE region.

TABLE 1.

Densitometry of genomic footprintsa

| Cells | Guanine position | % Methylation in the presence of E2 at the following h:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3 | 12 | ||

| MCF-7 | −954 | 31 | ND | 61 |

| −949 | 105 | ND | 130 | |

| −945 | 114 | ND | 155 | |

| OVCA-433 | −954 | 98 | 62 | 46 |

| −950 | 79 | 72 | 59 | |

| −946 | 86 | 76 | 63 | |

| −944 | 73 | 67 | 50 | |

Genomic footprints (Fig. 2) were quantitated by densitometry. In vivo percent methylation of each guanine residue was calculated relative to methylation at the correspondnig guanine position in free-DNA (in vitro) reactions, followed by normalization of values obtained in ER-positive (MCF-7 and OVCA-433) cells to those obtained in ER-negative (MDA-MB231 and HeLa) cells. Values of <15% were taken as nonsignificant; ND, not determined.

In MDA-MB231 and HeLa cells, both of which do not express ERα (Fig. 2a), no genomic footprint was detectable over the region comprising the ERE, regardless of hormone treatment (Fig. 2c and e); this result suggests that no factors are bound to this region, at least in these cell backgrounds. The lack of a footprint in MDA-MB231 cells, which express low levels of human ERβ (1), further indicates that this receptor does not interact in vivo with the hTERT ERE. Overall, these results demonstrate that distinct and cell-type specific remodelling of chromatin takes place over the hTERT ERE upon hormonal induction and that the expression of ERα is required for this effect.

Functional characterization of the hTERT ERE.

Chimeric constructs containing the luciferase reporter fused to two fragments of the hTERT promoter, P-1009 and P-330 (6), only the first of which contains the ERE, were cotransfected with an ERα expression vector into NIH 3T3 murine fibroblasts and immortal HOSE WOO cells in the presence or absence of E2 (10−7 M). In NIH 3T3 cells, the combination of ERα and estrogen resulted in about 40-fold enhancement in the activity of the P-1009 promoter. Mutation of the hTERT ERE in P-1009Mut essentially abrogated the estrogen responsiveness of this construct (Fig. 3a). No estrogen-mediated activation was observed with the ERE-negative construct P-330. Similar results were obtained with WOO cells (Fig. 3b), although in this case the hormone-dependent induction of the P-1009 promoter was substantially less pronounced (about fourfold). This reduced responsiveness could be accounted for by the higher basal level of the promoter in WOO cells and/or by the effects of other cell-specific factors that may contribute to hTERT transcriptional regulation in ovarian cells.

The oncogene c-myc has been shown to activate telomerase through a variety of sites (45), and estrogens have been shown to activate c-myc (10). The two c-myc binding sites within the first 250 nucleotides upstream of the ATG are present in both the P-1009 and the P-330 constructs; therefore, the observed differences in the activation of these two reporters cannot be explained by the presence of these sites. Moreover, the lack of activation with P-1009Mut demonstrates specific dependence on the hTERT ERE. Thus, our data rule out an indirect effect of estrogens mediated by the activation of c-myc.

To expand on the results of the electrophorectic mobility shift assays and DNA footprinting experiments, the potential role of ERβ in hTERT promoter function was evaluated directly by cotransfection of the ERβ expression vector and the P-1009 reporter in NIH 3T3 cells (Fig. 3c). Unlike the results obtained with ERα and in agreement with the results of the band shift assays, no induction of promoter activity by ERβ over basal levels was observed in the presence of E2. Moreover, treatment with TAM, which is reported to activate ERβ via an AP1 binding site (34), did not elicit a promoter response. As expected, the addition of TAM virtually abrogated ERα transactivation. These results demonstrate that the ERE contained within the proximal 1 kb of the hTERT promoter is functional and is necessary for transcriptional regulation by ligand-activated ERα. In contrast, ERβ does not appear to mediate E2 induction of the hTERT promoter.

The ability of hTERT ERE to respond to E2 on its own was assessed by cloning a single copy of this element upstream of the TK promoter (hTERT-ERE-TK construct). With the control vector (TK), in which the reporter is under the control of the TK promoter (positions −105 to +51), there was no change in chloramphenicol acetyltransferase activity upon cotransfection with ERα and treatment with E2 (Fig. 3d). In contrast, the hTERT ERE was able to confer E2 inducibility (threefold) to the heterologous TK promoter, demonstrating the regulatory properties of this element.

Estrogen induction of telomerase activity and hTERT expression.

To further investigate the potential role of sex steroid hormones in the regulation of hTERT expression and of telomerase activity, we made use of normal HOSE cells, derived from estrogen-responsive tissue from which over 90% of ovarian tumors arise (23). HOSE cells express substantial levels of ERs (11, 15; data not shown), and specific transcripts for both ERα and ERβ as well as androgen and progesterone receptors are detectable in these cells in postmenopausal women (15). These properties, together with the lack of telomerase activity, make HOSE cells a suitable model to study the role of steroid hormones in telomerase regulation.

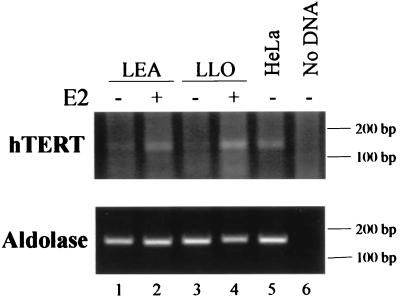

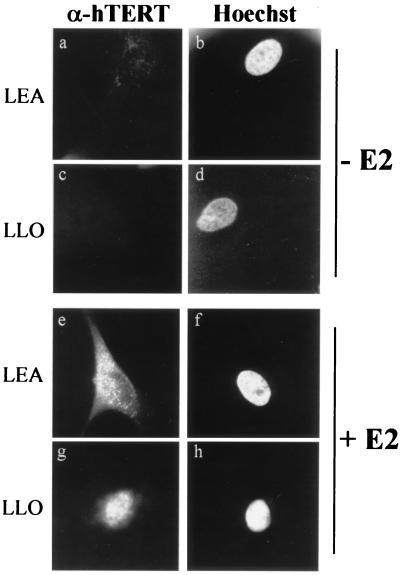

To assess whether transcriptional induction of hTERT promoter activity by E2 was paralleled by the induction of hTERT mRNA expression in estrogen-sensitive tissues, hTERT mRNA levels were measured in HOSE cells by semiquantitative RT-PCR. In the absence of hormone, no expression of hTERT mRNA was detected, whereas treatment with E2 for 6 h resulted in the appearance of a product corresponding to the amplified hTERT cDNA fragment (Fig. 4). The prompt estrogen induction of hTERT mRNA is in agreement with a regulatory mechanism acting at the transcriptional level. In addition to the mRNA, expression of the hTERT protein in the same set of primary ovarian cells was monitored by indirect immunofluorescence. Figure 5 shows the results obtained with LEA (Fig. 5a, b, e, and f) and LLO (Fig. 5c, d, g, and h) cells stained with antibody K-370 to the telomerase protein (Fig. 5a, c, e, and g). As a control, telomerase-positive, ERα-negative HeLa cells were included in each assay (data not shown). In the absence of hormone, no fluorescent signal was detected (Fig. 5a and c), in agreement with the lack of hTERT transcripts. The addition of E2 (Fig. 5e and g) for 6 h resulted in specific staining in over 70% of the cells. The staining pattern was predominantly nuclear and punctuated, as described for hTERT (14, 29). However, in the majority of LEA cells, staining extended to the cytoplasm (Fig. 5e); the reason for this dual pattern in not clear, but the morphology of cells with nuclear and cytoplasmic staining suggested that they might be approaching senescence.

FIG. 4.

Expression of hTERT mRNA in HOSE cells upon estrogen treatment. Total RNA was extracted from LEA (lanes 1 and 2) and LLO (lanes 3 and 4) cells grown in the presence (+) or absence (−) of 10−7 M E2 for 6 h. RT-PCR analysis was performed using primers specific for the hTERT and housekeeping aldolase genes and the conditions described in Materials and Methods. Lane 5, HeLa cell RNA as a control; lane 6, no cDNA template. Positions of molecular size markers are indicated.

FIG. 5.

Induction of hTERT expression by E2. LEA (a, b, e, and f) and LLO (c, d, g, and h) cells were grown in the absence (a to d) or presence (e to h) of E2 and stained with anti-hTERT antibody K-370 (a, c, e, and g) or with Hoechst 33258 (b, d, f, and h). Uninduced cells (a and c) did not express hTERT, while treatment with the hormone for 6 h resulted in abundant nuclear accumulation of the protein (e and g). Magnification, ×85.

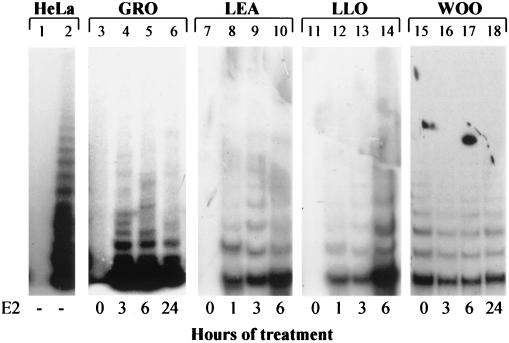

Finally, telomerase activity in extracts of HOSE cell strains (GRO, LEA, and LLO) and in immortal HOSE cells (WOO) grown in the absence or presence of estrogens was assayed by TRAP (Fig. 6). As reported previously (8), extracts from mortal cells were telomerase negative in the uninduced state (Fig. 6, lanes 3, 7, and 11). Upon the addition of E2 (10−7 M) to the culture medium, telomerase activity was induced within 3 h of treatment and increased marginally by 6 h. By 24 h, enzymatic activity was reduced, likely because of E2 intracellular catabolism (46). No hormonal induction of telomerase activity was observed in human embryonic kidney cells, which are telomerase negative and non-estrogen responsive (data not shown). Extracts from immortal WOO cells were telomerase positive, even in the absence of E2 (8); estrogen treatment did not induce significant changes in telomerase activity (Fig. 6, lanes 15 to 18), suggesting that once telomerase reactivation has taken place (here through cell immortalization), no estrogen-dependent modulation of enzymatic activity is detectable.

FIG. 6.

Telomerase activity in response to E2 treatment. Telomerase activity was assayed by TRAP in extracts from GRO (lanes 3 and 4), LEA (lanes 7 to 10), LLO (lanes 11 to 14), and WOO (lanes 15 to 18) cells. Assays shown were performed with 5 μg of protein, except in the case of WOO cells (10 μg of protein; similar results were obtained with 1 μg of protein). Cells were grown in the presence of E2 at 10−7 M for the indicated times. As positive and negative controls, 0.1 μg of protein from telomerase-positive HeLa cells was assayed before and after heat inactivation (no E2) (lanes 2 and 1, respectively).

Taken together, the above results indicate that estrogen treatment induces de novo hTERT expression and telomerase activity in telomerase-negative primary ovary epithelial cells with rapid kinetics strongly indicative of hormone-dependent transcriptional regulation of the hTERT gene. Our results differ from those of Tanaka et al. (41), who failed to detect changes in telomerase activity upon estrogen treatment of human endometrial cells. However, as the authors themselves suggested, this lack of response may have been related to the cells used, telomerase-positive endometrial cells that were unable to proliferate in vitro. Moreover, it has been shown that estrogen effects on the endometrium are mediated indirectly by ER-positive stromal cells (7).

In conclusion, the finding that hormone treatment of telomerase-negative ovary epithelium cells activates hTERT expression and telomerase provides, to our knowledge, the first direct evidence that a “physiological” stimulus may reverse telomerase silencing in normal cells. In addition, the identification of the hTERT gene as a target of hormones greatly advances the understanding of telomerase regulation in normal and malignant hormone-dependent cells and provides a suitable model for investigating the effects of steroid hormones in cell senescence and oncogenesis.

After submission of this paper, Kyo et al. (26) reported the activation of hTERT expression and of telomerase by E2 in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Together with our results, these findings indicate that estrogens play a role in the regulation of telomerase expression in estrogen-targeted tissues under different physiological and pathological conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Jan-Ake Gustafsson for the ERβ expression vector and to Maria Blasco for antibody K-370. We also thank the anonymous reviewer for very helpful suggestions on the role of c-myc in the response of telomerase to estrogens.

This work was supported by grants from Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC), Ministero della Sanità, Ministero dell'Università e della Ricerca Scientifica e Tecnologica (MURST), and the National Cancer Institute of Canada (NCIC) to S.B.

S.M. and S.N. contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aldous W K, Marean A J, DeHart M J, Matej L A, Moore K H. Effects of tamoxifen on telomerase activity in breast carcinoma cell lines. Cancer. 1999;85:1523–1529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beato M, Sanchez-Pacheco A. Interaction of steroid hormone receptors with the transcription initiation complex. Endocrinol Rev. 1996;17:587–609. doi: 10.1210/edrv-17-6-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bednarek A K, Chu Y, Aldaz C M. Constitutive telomerase activity in cells with tissue-renewing potential from estrogen-regulated rat tissues. Oncogene. 1998;16:381–385. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodnar A G, Ouellette M, Frolkis M, Holt S E, Chiu C P, Morin G B, Harley C B, Shay J W, Lichtsteiner S, Wright W E. Extension of life-span by introduction of telomerase into normal human cells. Science. 1998;279:349–352. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown M, Sharp P A. Human estrogen receptor forms multiple protein-DNA complexes. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:11238–11243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cong Y S, Wen J, Bacchetti S. The human telomerase catalytic subunit hTERT: organization of the gene and characterization of the promoter. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:137–142. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooke P S, Buchanan D L, Young P, Seawan T, Brody J, Korach K S, Taylor J, Lubhan D B, Cunha G R. Stromal estrogen receptors mediate mitogenic effects of estradiol on uterine epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6535–6540. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Counter C M, Hirte H W, Bacchetti S, Harley C B. Telomerase activity in human ovarian carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2900–2904. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.2900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dey A, Thornton A M, Lonergan M, Weissman S M, Chamberlain J W, Ozato K. Occupancy of upstream regulatory sites in vivo coincides with major histocompatibility complex class I gene expression in mouse tissues. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:3590–3599. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.8.3590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubik D, Shiu R P C. Mechanism of estrogen activation of c-myc oncogene expression. Oncogene. 1992;7:1587–1594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Grandien K, Lagercrantz S, Lagercrantz J, Nordenskjold C, Gustafsson J A. Human estrogen receptor beta-gene structure, chromosomal localization and expression pattern. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:4258–4265. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.12.4470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farsetti A, Misiti S, Citarella F, Felici A, Andreoli M, Fantoni A, Sacchi A, Pontecorvi A. Molecular basis of estrogen regulation of Hageman factor XII gene expression. Endocrinology. 1995;136:5076–5083. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.11.7588244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green S, Issemann I, Sheer E. A versatile in vivo and in vitro eucaryotic expression vector for protein engineering. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;16:369. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.1.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrington L, Zhou W, McPhail T, Oulton R, Yeung D S K, Mar V, Bass M B, Robinson M O. Human telomerase contains evolutionarily conserved catalytic and structural subunits. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3109–3115. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.23.3109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hillier S G, Anderson R A, Williams A R, Tetsuka M. Expression of oestrogen receptor alpha and beta in cultured human ovarian surface epithelial cells. Mol Hum Reprod. 1998;4:811–815. doi: 10.1093/molehr/4.8.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holt S E, Shay J W. Role of telomerase in cellular proliferation and cancer. J Cell Physiol. 1999;180:10–18. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199907)180:1<10::AID-JCP2>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horikawa I, Cable P L, Afshari C, Barrett J C. Cloning and characterization of the promoter region of human telomerase reverse transcriptase gene. Cancer Res. 1999;59:826–830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horwitz K B, McGuire W L. Estrogen control of progesterone receptor in human breast cancer. J Biol Chem. 1987;266:1008–1013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horwitz K B, Jackson T A, Bain D L, Richer J K, Takimoto G S, Tung L. Nuclear receptor coactivators and corepressors. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:1167–1177. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.10.9121485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katzenellenbogen J A, O'Malley B W, Katzenellenbogen B S. Tripartite steroid hormone receptor pharmacology: interaction with multiple effector sites as a basis for the cell- and promoter-specific action of these hormones. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:119–131. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.2.8825552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kilian A, Bowtell D D L, Abud H E, Hime G R, Venter D J, Keese P K, Duncan E L, Reddel R R, Jefferson R A. Isolation of a candidate human telomerase catalytic subunit gene, which reveals complex splicing patterns in different cell types. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:2011–2019. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.12.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim N W, Wu F. Advances in quantification and characterization of telomerase activity by the telomeric repeat amplification protocol (TRAP) Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2595–2597. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.13.2595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kommos F. Gynaecological cancer. In: Pasqualini J R, Katzenellenbogen B S, editors. Hormone-dependent cancer. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1996. pp. 541–572. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuiper G G, Lemmen J G, Carlsson B, Corton J C, Safe S H, van der Saag P T, van der Burg B, Gustafsson J A. Interaction of estrogenic chemicals and phytoestrogens with estrogen receptor beta. Endocrinology. 1998;139:4252–4263. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.10.6216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kyo S, Takakura M, Kohama T, Inoue M. Telomerase activity in human endometrium. Cancer Res. 1997;57:610–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kyo S, Takakura M, Kanaya T, Zhuo W, Fujimoto K, Nishio Y, Orimo A, Inoue M. Estrogen activates telomerase. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5917–5921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lau K M, Mok S C, Ho S M. Expression of mouse telomerase catalytic subunit in embryos and adult tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5722–5727. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lazennec G, Ediger T R, Petz L N, Nardulli A M, Katzenellenbogen B S. Mechanistic aspects of estrogen receptor activation probed with constitutively active estrogen receptors: correlations with DNA and coregulator interactions and receptor conformational changes. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:1375–1386. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.9.9983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin-Rivera L, Herrera E, Albar J P, Blasco M A. Expression of mouse telomerase catalytic subunit in embryos and adult tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10471–10476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meeker A K, Sommerfeld H J, Coffey D S. Telomerase is activated in the prostate and seminal vesicles of castrated rats. Endocrinology. 1996;137:5743–5746. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.12.8940411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moretti F, Farsetti A, Soddu S, Misiti S, Crescenzi M, Filetti S, Andreoli M, Sacchi A, Pontecorvi A. P53 re-expression inhibits proliferation and restores differentiation of human thyroid anaplastic carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 1997;14:729–740. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mueller P R, Salser S J, Wold B. Constitutive and metal-inducible protein: DNA interactions at the mouse metallothionein I promoter examined by in vivo and in vitro footprinting. Genes Dev. 1988;2:412–427. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.4.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nugent C I, Lundblad V. The telomerase reverse transcriptase: components and regulation. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1073–1085. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.8.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paech K, Webb P, Kuiper G G J M, Nilsson S, Gustafsson J-A, Kushner P J, Scanlan T S. Differential ligand activation of estrogen receptors ERα and ERβ at AP-1 site. Science. 1997;277:1508–1510. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Porter W, Saville B, Hoivik D, Safe S. Functional synergy between the transcription factor Sp1 and the estrogen receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:1569–1580. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.11.9916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodriguez G C, Berchuck A, Whitaker R S, Schlossman D, Clarke-Pearson D L, Bast R C., Jr Epidermal growth factor expression in normal ovarian epithelium and ovarian cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:745–750. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90508-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saito T, Schneider A, Martel N, Mizumoto H, Bulgay-Moerschel M, Kudo R, Nakazawa H. Proliferation-associated regulation of telomerase activity in human endometrium and its potential implication in early cancer diagnosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;231:610–614. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scholz A, Truss M, Beato M. Hormone-dependent recruitment of NF-Y to the uteroglobin gene enhancer associated with chromatin remodeling in rabbit endometrial epithelium. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4017–4026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.4017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takakura M, Kyo S, Kanaya T, Hirano H, Takeda J, Yutsudo M, Inoue M. Cloning of human telomerase catalytic subunit (hTERT) gene promoter and identification of proximal core promoter sequences essential for transcriptional activation in immortalized and cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1999;59:551–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanaka M, Takakura M, Kanaya T, Sagawa T, Yamashita K, Okada Y, Hiyama E, Inoue M. Expression of telomerase activity in human endometrium is localized to epithelial glandular cells and regulated in a menstrual phase-dependent manner correlated with cell proliferation. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:1985–1991. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65712-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ulaner G A, Hu J F, Vu T H, Giudice L C, Hoffman R. Telomerase activity in human development is regulated by human telomerase reverse transcriptase transcription and by alternative splicing of hTERT transcripts. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4168–4172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vaziri H, Benchimol S. Reconstitution of telomerase activity in normal human cells leads to elongation of telomeres and extended replicative life span. Curr Biol. 1998;8:279–282. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70109-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Webb P, Lopez G N, Uht R M, Kushner P J. Tamoxifen activation of the estrogen receptor/AP-1 pathway: potential origin for the cell-specific estrogen-like effects of antiestrogens. Mol Endocrinol. 1995;9:443–456. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.4.7659088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu K-J, Grandori C, Amacker M, Simon-Vermot N, Polack A, Lingner J, Dalla-Favera R. Direct activation of TERT transcription by c-Myc. Nat Genet. 1999;21:220–224. doi: 10.1038/6010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zimmermann H, Koytchev R, Mayer O, Borner A, Mellinger U, Breitbarth H. Pharmacokinetics of orally administered estradiol-valerate. Results of a single-dose cross-over bioequivalence study in postmenopausal women. Arzneimittelforschung. 1998;48:941–947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]