Abstract

In eukaryotes, alternative splicing refers to a process via which a single precursor RNA (pre-RNA) is transcribed into different mature RNAs. Thus, alternative splicing enables the translation of a limited number of coding genes into a large number of proteins with different functions. Although, alternative splicing is common in normal cells, it also plays an important role in cancer development. Alteration in splicing mechanisms and even the participation of non-coding RNAs may cause changes in the splicing patterns of cancer-related genes. This article reviews the latest research on alternative splicing in cancer, with a view to presenting new strategies and guiding future studies related to pathological mechanisms associated with cancer.

Keywords: Alternative splicing, cancer, splicing factors, isoforms, CircRNA

Introduction

Although more than 20,000 protein-coding genes were identified at the completion of the Human Genome Project, this number was far less than what was originally expected. Studies conducted later revealed that although the number of protein-coding genes is limited, different transcripts are generated by alternative splicing, leading to a large number of proteins with different functions. In fact, approximately 95% of human genes can be alternatively spliced [1,2]. For example, BIM, which consists of six exons, generates at least 18 different transcripts via alternative splicing [3]. Thus, alternative splicing greatly enhances the diversity and complexity of transcripts without altering the genome sequence and structure, thereby increasing the amount of genetic information. Thus, this process exerts an important effect on normal physiological and pathological processes.

Several studies have indicated that dysregulation of alternative splicing, which directly affects cell proliferation, apoptosis, invasion, migration, metabolism, and other characteristics of cancer cells, is closely associated with numerous diseases, including cancer [4]. Therefore, the identification of potential targets of alternative splicing may provide a basis for the development of new methods for cancer diagnosis and treatment. In this review, we introduce the general mechanisms underlying RNA splicing and discuss important factors that affect the process of alternative splicing. Next, we summarize specific mechanisms underlying the alternative splicing of cancer-related genes, according to cancer characteristics. Then, we describe the latest advances in alternative splicing related therapeutic strategies. Furthermore, we discuss the involvement of non-coding RNAs in the process of alternative splicing in cancer, in order to explore recent progress in the understanding of alternative splicing in relation to tumorigenesis and development.

RNA splicing process and alternative splicing

Mechanism of RNA splicing

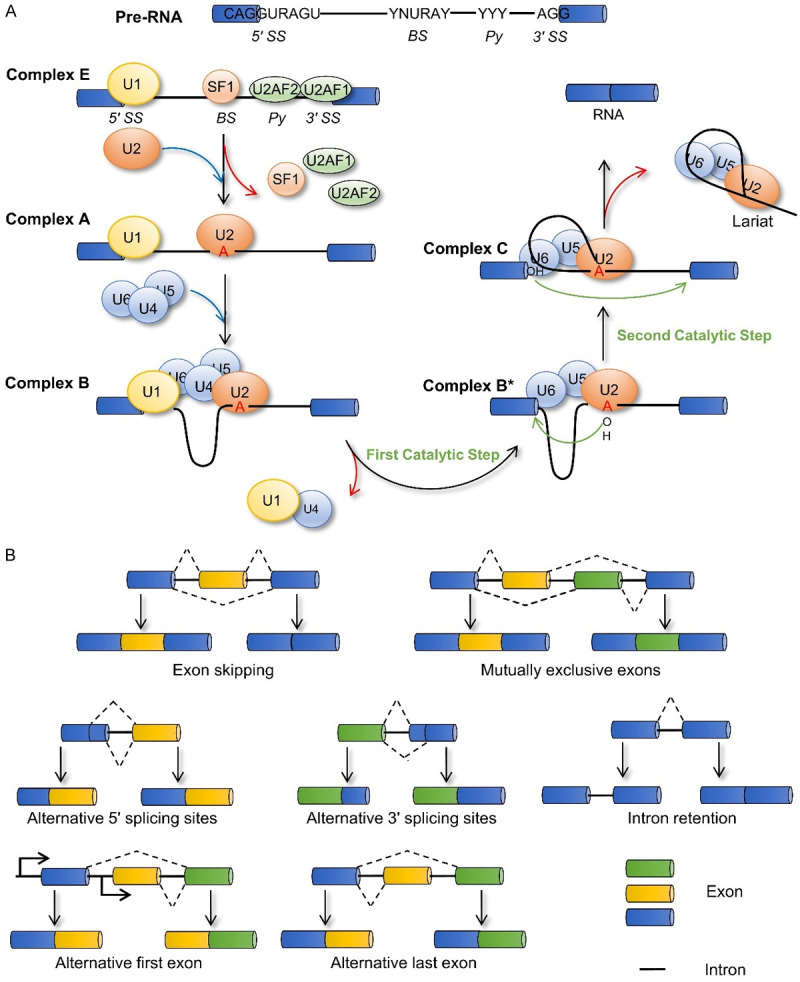

RNA splicing constitutes an important step in the process of transforming pre-RNA into mature RNA. During this process, the spliceosome, acting as “scissors”, plays a role in identifying splice sites and catalyzing splicing reactions. It is mainly composed of five small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs), U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6 [5]. The spliceosome enables pre-RNA to complete two transesterification reactions, which release a lariat-shaped intron and connect the upstream and downstream exons. First, the U1 snRNP binds to the 5’ splice site via base pairing between the small nuclear RNA and the splice site. The splicing helper, U2AF, consists of two isoforms: U2AF1, which recognizes the 3’ acceptor splice site; and U2AF2, which binds to the adjacent polypyrimidine region. Another helper, splicing factor 1 (SF1), binds to the branch site (BS). Subsequently, SF1 is displaced by U2 snRNP, which recognizes and binds to the BS on the intron via base pairing, thereby forming the A complex. The U4/U5/U6 snRNP complex then binds to the 5’ splice site to form the B complex. The instability of U1 and U4 snRNPs leads to their separation from the system, leading to a conformational rearrangement that forms an active B complex, wherein the U6 snRNP replaces the U1 snRNP. The interaction between U6 and U2 snRNPs causes the 2’ hydroxyl group of the conserved adenosine in the BS to attack the phosphate group of the conserved guanosine at the 5’ splice site. The intron released at the 5’ end completes the first transesterification reaction. Then, U5 snRNP participates in the completion of the second transesterification, causing the hydroxyl group of the 5’ end of the exon to attack the phosphate group of the 3’ splice site, thereby releasing the lariat-shaped intron and connecting the two adjacent exons (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Splicing mechanism and alternative splicing patterns. A. Following spliceosome assembly and two transesterification reactions, pre-RNA is finally transformed into mature RNA. B. Different RNA splicing patterns: Exon skipping, Mutually exclusive exons, Alternative 5’ or 3’ splicing sites, Intron retention, Alternative first exon, and Alternative last exon. BS, branch site; Py, polypyrimidine; 5’ SS, 5’ splicing site; 3’ SS, 3’ splicing site.

Regulatory factors of alternative splicing

The selection of splice sites in pre-RNA allows for the possibility of many RNA splicing patterns (Figure 1B). The main factors affecting selection are cis-acting elements and trans-acting factors. Cis-acting elements, which are mainly located at the 5’ or 3’ splice sites and BS, also include auxiliary cis-acting elements, such as exon splicing enhancers (ESEs), exon splicing silencers (ESSs), intron splicing enhancers (ISEs), and intron splicing silencers (ISSs). Classical trans-acting factors include the serine/arginine-rich (SR) protein family and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) family. Their interaction with ESEs/ISEs and ESSs/ISSs either promote or inhibit the recognition of splice sites (Figure 2). The effects of cis-acting elements and trans-acting factors on alternative splicing have been previously described in many review articles and are therefore not described in detail here [6-8].

Figure 2.

Multiple regulatory factors involved in alternative splicing. In addition to cis-acting elements and trans-acting factors, the elongation rate of RNA polymerase II during transcription affects the mode of alternative splicing, and histone modification plays an important role as a scaffold between transcription and alternative splicing. Moreover, m6A writers, readers, and erasers participate in alternative splicing. MRG15, Morf-related gene 15; PTB, polypyrimidine binding protein; H3K36me3, histone H3 Lys36 trimethylation; Pol II, RNA polymerase II; CTD, C-terminal domain; SR protein, serine/arginine-rich protein; hnRNP, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein; ESE, exon splicing enhancer; ESS, exon splicing silencer; ISE, intron splicing enhancer; ISS, intron splicing silencer; m6A, N6-methyladenine; YTHDC1, YTH domain containing 1; FTO, fat mass and obesity-associated protein; SRSF3, serine and arginine rich splicing factor 3; SRSF10, serine and arginine rich splicing factor 10; METTL16, methyltransferase like 16; METTL3, methyltransferase like 3; hnRNPA2B1, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2/B1; hnRNPG, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein G.

In eukaryotes, functional coupling occurs between alternative splicing and RNA transcription [9-11], suggesting that alternative splicing is affected by transcriptional regulation. The main C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II (Pol II) plays a key role in the processes of transcription and RNA splicing. It can induce the enrichment of splicing factors in newborn transcripts to increase their concentration and thus promote splicing [12,13]. Faster transcriptional elongation by Pol II facilitates the recruitment of splicing factors to strong splicing sites, resulting in exon skipping, whereas slower transcriptional elongation leads to exon inclusion. The pausing of Pol II at the exon provides sufficient time for spliceosome assembly. However, the distribution of nucleosomes seems to hinder the extension of Pol II [14]. In addition, chromatin structure, histone modification, and DNA methylation facilitate the coupling process of alternative splicing and transcription. For example, an adapter system composed of H3K36me3, binding protein MRG15, and splicing factor polypyrimidine binding (PTB) protein regulates alternative splicing events [15] (Figure 2).

Additionally, several studies have indicated that post-transcriptional modifications exert an important effect on alternative splicing. N6-methyladenine (m6A) modification is the most common and abundant mRNA alteration mechanism in eukaryotes [16]. Reportedly, the m6A-related enzymes, “reader”, “writer”, and “eraser”, were mainly located in nuclear speckles, which is consistent with the enrichment position of splicing factors. The knockdown of methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3) facilitates the expression of MyD88s, a MyD88 isoform, to inhibit the inflammatory process [17]. In bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, METTL3 knockdown altered the expression levels of vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) splicing variants [18]. Downregulation of METTL3 also altered the expression of related genes and the alternative splicing patterns in p53 signaling pathway components [19]. Methyltransferase-like 16 induces the splicing mode of which enables intron retention by methylating the hairpin structure of MAT2A [20]. The m6A reader, YTH domain containing 1 (YTHDC1), interacts with many SR proteins, where SRSF3 is recruited by YTHDC1 to prevent the splicing effect of SRSF10 on pre-RNA and promote exon inclusion. In contrast, SRSF10 promotes exon skipping in the absence of YTHDC1 [21,22]. Furthermore, hnRNPA2B1 and hnRNPG, acting as m6A readers, also affect the splicing of pre-RNA [23,24]. The depletion of fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) may also induce exon skipping events, whereas METTL3 and FTO reportedly exert opposing regulatory effects on the expression of internal and 3’ terminal exons [25]. However, studies investigating the relationship between m6A and alternative splicing are incomplete and this relationship needs further exploration.

Many studies have demonstrated that non-coding RNAs can also affect alternative splicing, which are described below. Thus, several complex factors affect alternative splicing, which consists of a fine regulatory network that acts as a premise for the maintenance of normal physiological activity of cells. It is important to study the function of these splicing factors in diseases caused by abnormal alternative splicing, with particular reference to cancer.

Alternative splicing is involved in the development of cancer

Alternative splicing has a far-reaching impact on the occurrence and development of cancer, by affecting almost all characteristics of cancer cells. Therefore, the splicing isoforms of cancer-related genes are potential therapeutic targets worthy of our attention. Moreover, the regulation of alternative splicing by lncRNAs and microRNAs (miRNAs) provides a more comprehensive understanding of the role of non-coding RNAs, which in turn may help develop and apply new methods and strategies for cancer therapy. Here, we describe mechanisms associated with alternative splicing with the expectation that this information may enable a better understanding of the important role played by cancer-related genes in cancer development.

Alternative splicing and cell proliferation

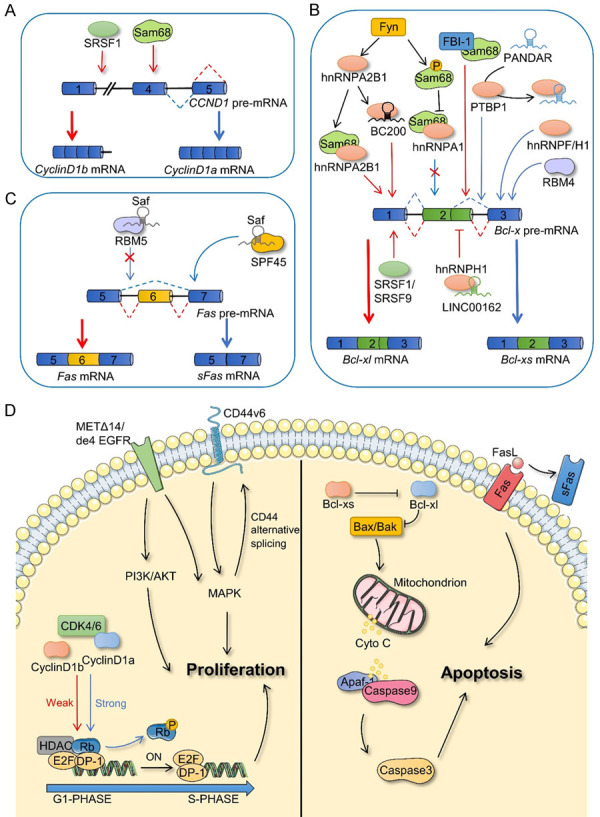

In normal cells, cell proliferation is an orderly and stable process to ensure a dynamic balance of cell numbers. However, long-term abnormal proliferation is a typical characteristic of cancer cells, and the proliferation of cancer cells is often closely related to the cell cycle and growth rate. For example, CCND1 encodes cyclin D1a and cyclin D1b, the two isoforms of cyclin D1, which are upregulated in many cancers. Unlike cyclin D1a mRNA, cyclin D1b mRNA does not retain all exons [26]. The production of cyclin D1b is promoted by the splicing factor, Sam68, which interferes with the recruitment of U1 snRNP by binding to intron 4. Similarly, SRSF1 has also been implicated as a splicing factor in the alternative splicing of CCND1. Importantly, the formation of cyclin D1b is associated with G/A polymorphism at the exon 4 and intron 4 junctions of CCND1 (nucleotide 870), and Sam68 and SRSF1 are associated with this polymorphism [27,28]. Cyclin D1a forms a complex with cyclin-dependent kinase 4 or 6 (CDK4/6) to activate phosphorylation of the tumor suppressor protein Rb, which in turn promotes cell cycle progression and affects cell proliferation. Although cyclin D1b retains the ability to bind CDK4, its capacity to induce Rb phosphorylation is markedly inadequate [29,30]. However, compared with cyclin D1a, cyclin D1b effectively induces cell transformation and displays a more pronounced carcinogenic potential [27,31]. Moreover, it was independently associated with prognoses and was not affected by the expression of cyclin D1a [32]. However, it has been shown that Cyclin D1b inhibits cancer growth by antagonizing cyclin D1a [33]. Therefore, cyclin D1b-mediated tumorigenesis warrants further research (Figure 3A, 3D).

Figure 3.

Alternative splicing in cell proliferation and apoptosis. A. Splicing factors affect the alternative splicing process of CCND1. B. The pathways involved in the alternative splicing of Bcl-x to form Bcl-xl and Bcl-xs isoforms. C. Fas and sFas are alternative splicing products of Fas. D. CCND1 splicing products (Cyclin D1b and Cyclin D1a), CD44 splicing products (CD44v6), and receptor tyrosine kinase families (METΔ14 and de4 EGFR) affect cell proliferation (left). Splicing products of Fas and Bcl-x play a functional role in apoptosis (right). SRSF1, serine and arginine rich splicing factor 1; Fyn, Src family tyrosine kinase; FBI-1, factor binding IST protein 1; RBM5, RNA-binding motif 5; RBM4, RNA-binding motif 4; SPF45, RNA binding motif protein 17; PTBP1, epithelial splicing regulatory protein 1; hnRNPA1, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1; hnRNPA2B1, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2/B1; hnRNPH1, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein H1; hnRNPF, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein F; SRSF9, serine and arginine rich splicing factor 9; METΔ14, MET which lacks exon 4; de4 EGFR, EGFR which has exon 4 excluded; CDK4/6, cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6; HDAC, histone deacetylase; P, phosphorylation; Bcl-x, B-cell leukemia x; Bcl-xs, Bcl-x short isoform; Bcl-xl, Bcl-x long isoform; BAX, BCL2-associated X; BAK, BCL2 Antagonist/Killer 1; Apaf-1, Apoptotic peptidase activating factor 1; Cyto C, Cytochrome C; Fas, Fas cell surface death receptor; sFas, soluble Fas; FasL, Fas ligand.

In addition, proliferation-related signaling pathways regulate alternative splicing of related genes. For example, CD44, a type I transmembrane glycoprotein receptor, is closely associated with cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis. Hundreds of transcripts generated by CD44 via alternative splicing are classified as CD44v and CD44s isoforms, and show phenotypic differences in many types of cancers. The phorbol ester-activated MAPK signaling pathway enhances CD44 splicing, which requires ERK-mediated phosphorylation of Sam68. The amino acids, Ser58, Thr71, and Thr84, are the main phosphorylation sites of Sam68 that are targeted by ERK, which regulates alternative splicing of CD44 [34]. The expression of SWI/SNF subunit BRM, a chromatin remodeling protein, also affects CD44 splicing, and its interaction with Sam68 and U5 snRNP suggests that this protein may, together with Sam68, play a role as a bridge for recruiting spliceosomes and mediate the elongation rate of Pol II in CD44 [35]. The transcriptional coactivator SND1 interacts with Sam68. Although SND1 does not affect the elongation rate of Pol II in CD44, it is required for the binding of Sam68 to Pol II [36]. Reportedly, a positive feedback loop exists between CD44 alternative splicing and the MAPK signaling pathway. In this cycle, MAPK signaling affects CD44 alternative splicing by regulating splicing factors, whereas the CD44v6 variant forms complexes with a growth factor, HGF, and a receptor tyrosine kinase, MET, to maintain the MAPK signal [37] (Figure 3D).

Receptor protein tyrosine kinases, which activate the downstream MAPK and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways, play an important role in cell proliferation and motility. Alternative splicing induces formation of different isoforms of many cell surface receptors, thereby regulating cancer cell proliferation. For example, a classical splicing isoform of the epidermal growth factor receptor lacking exon 4 (de4 EGFR) exists in many cancer cells, but not in adjacent normal tissues [38]. METΔ14, a splicing isoform of the tyrosine kinase MET, is considered to be a potential driver of lung cancer [39] (Figure 3D). In breast cancer, the splicing of the epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) is regulated by SRSF3 and hnRNPH1, where SRSF3 knockdown causes transformation of the HER2 splice variant Δ16HER2 into P100, which contains exon 15 and inhibits cell proliferation [40].

These data indicate that changes in alternative splicing of related genes induce dysregulation in the proliferation signaling pathway. Ultimately, this disorder promotes cell proliferation and is conducive to cancer progression.

Alternative splicing and cell apoptosis

During tumorigenesis, cancer cells become desensitized to apoptosis signals, thereby hindering programmed cell death and entering a state of disordered and unchecked growth. The two established classical pathways of apoptosis are as follows: exogenous apoptosis mediated by death receptors and endogenous apoptosis induced by mitochondria.

The endogenous apoptosis pathway involves B-cell leukemia-2 family proteins, which are also regulated by alternative splicing. For example, the isoforms of B-cell leukemia x (Bcl-x), generated through alternative splicing, possess opposing biological functions. Bcl-x, specifically, is composed of three exons. The selection of the proximal 5’ splicing site in exon 2 produces the Bcl-xl isoform, which has an anti-apoptotic function, whereas selection of the distal 5’ splicing site in exon 2 produces the apoptotic Bcl-xs isoform. Moreover, Bcl-xs activates the downstream proteins, Bax and Bak, by inhibiting the Bcl-xl isoform. The permeability of the mitochondrial outer membrane is altered, releasing cytochrome C, leading to the formation of an apoptosome with Apaf-1 and caspase-9. This apoptosome further activates caspase-3, eventually leading to cell apoptosis [41-43]. Therefore, alternative splicing of Bcl-x may directly regulate the ratio of intracellular Bcl-xl/Bcl-xs, thereby affecting cell survival. Studies have shown that classical splicing factors, SR proteins and hnRNPs, such as SRSF1 (ASF/SF2) [44,45], SRSF9 [46], PTBP1 (hnRNP I) [45], hnRNPF, hnRNPH1 [47], and hnRNPA2B1 [48], are involved in the alternative splicing of Bcl-x. In addition, other RNA-binding proteins are also involved in the alternative splicing of Bcl-x. For example, Sam68 is considered to be a regulator of alternative splicing of Bcl-x. The kinase, Fyn, induces tyrosine phosphorylation of Sam68 and blocks the interaction between Sam68 and hnRNPA1, thus promoting the formation of the Bcl-xl isoform [44]. Moreover, hnRNPA2B1 is also regulated by Fyn to promote the formation of Bcl-xl and cooperate with Sam68 in regulating apoptosis [48]. BC200 is an estrogen-regulated lncRNA containing a 17 bp sequence that complements the 3-UTR of Bcl-x mRNA, eventually recruiting hnRNPA2B1 to promote the expression of the Bcl-xl isoform [49]. This indicates that alternative splicing is not only regulated by protein-protein interactions, but also by non-coding RNAs, which display catalytic splicing ability. Other non-coding RNAs, such as LINC00162 [50] and PANDAR [51], also participate in the alternative splicing of Bcl-x. Furthermore, the interaction between the transcription factor FBI-1 and Sam68, hinders the recruitment of Sam68 to Bcl-x precursor messenger RNA (pre-mRNA) to participate in splicing, which leads to transformation of the Bcl-xs isoform to the Bcl-xl isoform. However, this interaction does not interfere with the interaction between Sam68 and other splicing factors. Histone deacetylase may modulate FBI-1-mediated Bcl-x splicing by altering the chromatin structure or affecting the process of RNA transcription [52] (Figure 3B, 3D).

In the exogenous apoptosis pathways, Fas, a cancer necrosis factor receptor, triggers apoptosis by binding to the Fas ligand (FasL). However, Fas pre-mRNA produces an antiapoptotic soluble isoform, sFas, via exon 6 skipping [53]. Several splicing regulators are reportedly involved in regulating the splicing process of Fas [54-57]. Recently, hypoxic microenvironments were found to regulate Fas splicing and promote the production of anti-apoptotic sFas mRNA. However, the function of related splicing factors remains to be studied [58]. Interestingly, Saf, a type of antisense transcriptional lncRNA of Fas, was shown to interact with the splicing factor SPF45 (also known as RBM17) to promote the production of sFas, which binds to FasL and blocks Fas-mediated apoptosis [59], whereas the combination of Saf and RBM5 prevents the skipping of exon 6 of Fas pre-mRNA [60] (Figure 3C, 3D).

In conclusion, Bcl-x and Fas play critical roles in the regulation of exogenous and endogenous apoptosis pathways, and thus, investigating their splicing variants may provide a new direction in cancer therapy.

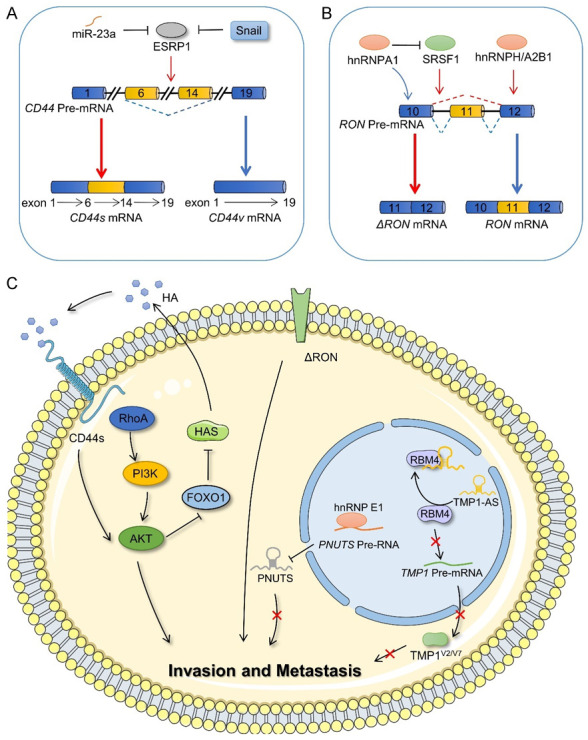

Alternative splicing in the invasion and metastasis of cancer cells

Invasion and metastasis of cancer cells are considered the most difficult issues affecting cancer therapy [61-68]. Epithelial-mesenchymal transformation (EMT) is reported to be the key mechanism underlying the metastatic and invasive abilities of epithelial tissue-derived malignant tumors [69]. Transforming CD44v to CD44s is considered as a strategy that may enable the regulation of EMT in cancer cells [70-72]. Epithelial splicing regulatory protein 1 (ESRP1) plays a negative regulatory role in this transformation and inhibits the occurrence of EMT [71,73,74]. In recent years, many upstream factors have been reported to target ESRP1 to regulate the splicing events of CD44 pre-mRNA. For example, the transcription factor, Snail, inhibits the transcription of ESRP1 by binding its promoter region, thereby interfering with the splicing process of CD44 pre-mRNA and enhancing the invasion and metastatic abilities of cancer cells [75]. In pancreatic cancer cells, miR-23a plays a tumor-promoting role by inhibiting ESRP1 expression and inducing the transformation of CD44v to CD44s [76] (Figure 4A). Another study suggested that the CD44s isoform inhibits the activity of the transcriptional inhibitor FOXO1 by activating the AKT signal and promoting the transcription of hyaluronidase 2 (HAS2). HAS2 encodes hyaluronic acid, the ligand of CD44s, which can further stimulate the CD44-AKT pathway, finally forming a closed-loop of positive feedback regulation to promote EMT and cancer cell survival [77] (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Alternative splicing in the invasion and metastasis of cancer cells. A. Alternative splicing of CD44 and splicing factors that affect the splicing process of CD44. B. RON generates RON and ΔRON isoforms by alternative splicing and involves the participation of other splicing factors. C. The regulatory mechanism of CD44s, ΔRON, PUNTS, and TMP1V2/V7 splicing isoforms on cell invasion and metastasis. ESRP1, epithelial splicing regulatory protein 1; hnRNPA1, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1; hnRNPH, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein H; hnRNPA2B1, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2/B1; SRSF1, serine and arginine rich splicing factor 1; RhoA, Ras homolog family member A; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; AKT, AKT serine/threonine kinase; FOXO1, forkhead box O1; HAS, hyaluronidase 2; HA, hyaluronic acid; RBM4, RNA-binding motif 4; hnRNPE1, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein E1.

RON is a tyrosine kinase receptor, which binds human macrophage-stimulating protein. The overexpression of its isoform, ΔRON, resulting from skipping exon 11 in RON pre-mRNA, enhances the invasive ability of cancer cells. Moreover, SRSF1 promotes ΔRON expression [78,79]. However, binding between hnRNPA1 and ESS sequence in exon 12 interferes with the interaction between SRSF1 and ESE elements, thereby inhibiting ΔRON production [80]. Furthermore, hnRNPA2B1 and hnRNPH are also involved in the splicing process in glioblastomas [81,82] (Figure 4B, 4C).

Similarly, non-coding RNAs can also regulate the alternative splicing of downstream target genes via different mechanisms, thus affecting the migration and invasion of cancer cells. For example, the lncRNA, TPM1-AS, binds RBM4 to prevent interaction between RBM4 and TPM1-AS pre-mRNA, thus affecting the alternative splicing of human tropomyosin 1 (TPM1) and causing the downregulation of TPM1 isoforms, V2 and V7. This inhibits the formation and migration of filamentous pseudopodia of cancer cells [83]. PNUTS pre-RNA can generate PNUTS mRNA and lncRNA PNUTS via alternative splicing. HnRNPE1 inhibits the formation of lncRNA PNUTS by binding to the BAT element at the splicing site of PNUTS pre-RNA, thus regulating cancer cell migration and invasion [84] (Figure 4C).

These data suggest that the splicing variants of related genes may be key switches affecting invasion and metastasis.

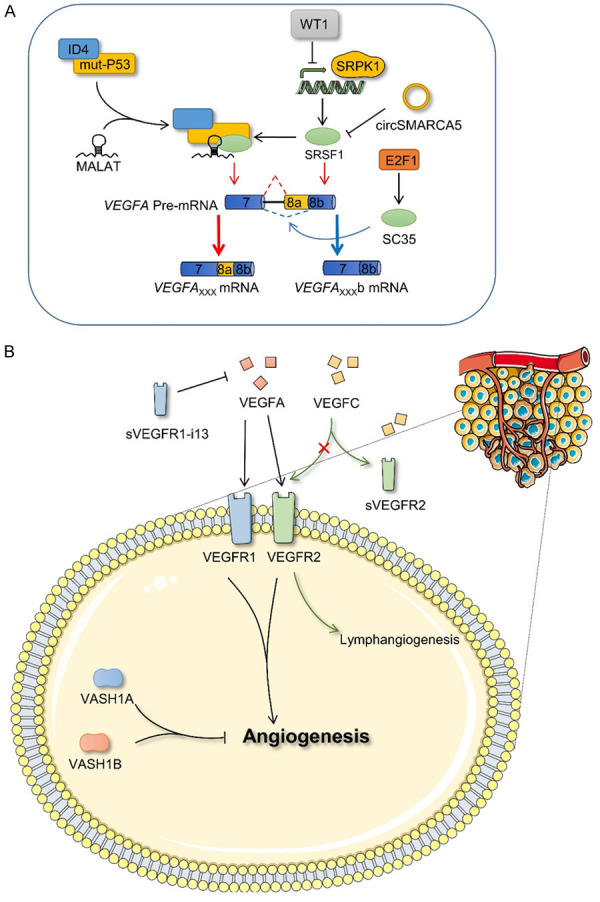

Alternative splicing and angiogenesis

Angiogenesis, which is a major characteristic of cancer, enables the continuous expansion of cancer cells [85,86]. VEGFA is the most common angiogenesis-inducing factor. VEGFA contains eight exons, and selecting the proximal 3’ splicing site in exon 8 produces pro-angiogenic VEGFA××× isoforms, which are upregulated in cancer, whereas selecting the distal 3’ splicing site in exon 8 promotes the formation of anti-angiogenic VEGFA×××b isoforms, the expression of which is low in most cancer types (the subscript××× indicates the number of amino acids in different isomers) [87]. The splice factor SR protein family is closely associated with the alternative splicing of VEGFA. For example, WT1 inhibits the expression of SRSF protein kinase 1 (SRPK1) by binding to its promoter. In WT1 mutant cells, the upregulation of SRPK1 expression leads to greater phosphorylation of SRSF1, which regulates alternative splicing of VEGFA and cancer growth [88]. The transcription factor, E2F1, influences the ratio of VEGFA×××a/VEGFA×××b by inducing the expression of an SR family protein, SC35 (also known as SRSF2), to promote the formation of the anti-angiogenic isoform [89]. In addition, non-coding RNAs are also involved in the alternative splicing of VEGFA. Mutant P53/ID4/MALAT/SRSF1 complexes in breast cancer affect VEGFA pre-mRNA splicing to promote the formation of the angiogenic isoform [90]. CircSMARCA5 affects the splicing of VEGFA pre-mRNA through SRSF1 in pleomorphic glioblastoma [91] (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Alternative splicing and angiogenesis. A. VEGFA forms VEGFA××× and VEGFA×××b isoforms via alternative splicing. SRSF1 and SC35 (also known as SRSF2) promote formation of the two VEGFA isoforms and these splicing factors are regulated by other proteins and non-coding RNA, which indirectly affect the splicing of VEGFA. B. Regulation of angiogenesis by different splicing isoforms of VEGFR and VASH1. ID4, inhibitor of DNA binding 4; SRPK1, SRSF growth factor 1; E2F1, E2F transcription factor 1; VEGFA, vascular endothelial growth factor A; VEGFC, vascular endothelial growth factor C; VEGFR1, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1; VEGFR2, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2; sVEGFR2, soluble VEGFR2; VASH1A, vasohibin 1 A isoform; VASH1B, vasohibin 1 B isoform.

However, the VEGFA family must bind to the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) on the cell surface to exert its biological effects via a series of signaling pathways. Among them, VEGFA mainly binds to VEGFR2, whereas sVEGFR2, a soluble splicing isoform of VEGFR2, does not affect angiogenesis but inhibits the proliferation of human lymphangioma endothelial cells induced by VEGFC [92]. At present, four splice variants of VEGFR1 have been identified. Of these four, sVEGFR1-i13 is considered a natural antagonist of VEGFA [93]. In addition, vasohibin 1 (VASH1), an angiogenesis inhibitor, produces different transcripts via alternative splicing, including the VASH1A and VASH1B isoforms, both of which inhibit cancer growth and angiogenesis, although their effects on cancer vessels differ. Interestingly, the comprehensive application of both reportedly contributes to the efficacy of anti-angiogenesis therapy [94] (Figure 5B).

These data suggest that alternative splicing plays a significant role in angiogenesis.

Alternative splicing and metabolism

Compared with that of normal cells, the metabolic pattern of cancer cells is altered, with the most marked change occurring in the glucose metabolism pathway [95]. Even under conditions of oxygen sufficiency, cancer cells preferentially use aerobic glycolysis (also known as the Warburg effect) to convert glucose into lactic acid, which allows these cells to obtain energy more rapidly. Pyruvate kinase M1 (PKM1) and pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2), which are formed by the alternative splicing of PKM pre-mRNA, influence the Warburg effect and have been widely studied in the field of cancer. However, the results of previous studies on PKM1 and PKM2 have been subject to controversy and require further exploration [96,97]. Concluding that PKM2 promotes aerobic glycolysis and thereby cancer growth, whereas PKM1 promotes aerobic phosphorylation and inhibits cancer development, appears to be too simplistic. Studies have shown that PTBP1, hnRNPA1, and hnRNPA2, which are regulated by c-Myc, specifically bind to the flanking sequence of exon 9, inducing the formation of the PKM2 isoform [98]. However, the downregulation of PTBP1 promotes the production of PKM1 and reduces drug resistance in pancreatic ductal carcinoma cells [99]. Furthermore, miR-124 and miR-206 reportedly target PTBP1 and hnRNPA1, respectively, in colorectal cancer, thereby regulating the transformation of PKM2 to PKM1 [100,101]. NEK2, a serine/threonine kinase, regulated by c-Myc at the transcriptional level, also interacts with hnRNPA1/2 to regulate the PKM1/PKM2 ratio, thus promoting aerobic glycolysis in myeloma cells [102]. In hepatocellular carcinoma, RNA helicase MTR4 binds to the intron of PKM pre-mRNA to regulate its alternative splicing process by recruiting PTBP1, and c-Myc promotes the transcription of MTR4 [103]. LncRNAs have almost no protein-coding function, and therefore, it is difficult to recognize functional short open reading frames in lncRNAs. However, a study demonstrated that the lncRNA, HOXB-AS3, produces HOXB-AS3 peptides, which competitively bind to the splicing factor hnRNPA1 to promote the formation of PKM1, thus inhibiting the reprogramming of glucose metabolism and the development of colorectal cancer [104]. Moreover, ChiRP-MS and bioinformatics analyses indicated that lncRNA SNHG6 interacts with hnRNA1 to increase the ratio of PKM2/PKM1 in colorectal cancer [105] (Figure 6A, 6B). These findings suggest that PKM1 and PKM2 may be therapeutic targets in glucose metabolism.

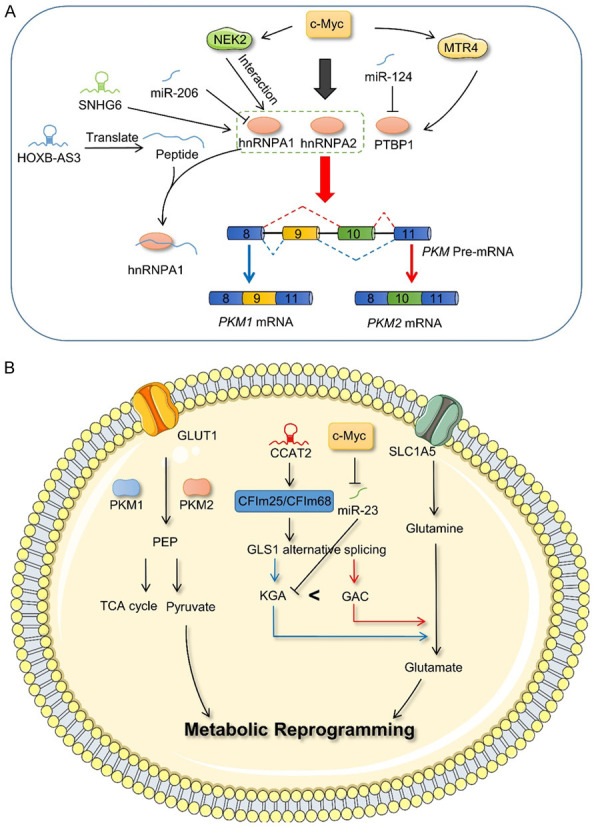

Figure 6.

Alternative splicing and metabolism. A. PKM forms PKM1 and PKM2 isoforms via alternative splicing, wherein PTBP1, hnRNPA1, hnRNPA2, splicing factors are regulated by c-Myc and non-coding RNAs. B. PKM1 and PKM2 play a functional role in the glycolysis pathway, and lncRNA CCAT2 and miR23 affect the expression of KGA and GAC, thereby regulating the process of glutamine metabolism. NEK2, NIMA-related kinase 2; hnRNPA1, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1; hnRNPA2, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2; PTBP1, polypyrimidine tract binding protein 1; PKM1, pyruvate kinase M1; PKM2, pyruvate kinase M2; GLUT1, glucose transporter 1; SLC1A5, solute carrier family 1 member 5; GLS1, glutaminase 1; CFIM, cleavage factor I; KGA, glutaminase kidney isoform; GAC, glutaminase isoform C; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate.

However, glycolysis is not the sole mechanism via which cancer cells obtain energy. Glutamine metabolism in mitochondria also acts as an “energy refueling base” for cancer cells [106]. Glutaminase (GLS), which is known to convert glutamine to glutamate and ammonia, has two isoforms, GLS1 and GLS2. Of these, GLS1 forms two main splice variants, GAC and KGA, which have different 3’ UTR regions, via alternative splicing. The large-scale analysis of clinical sample data has shown that GLS exerts a strong alternative splicing-coupled 3’ UTR shift effect in cancer, which leads to transition from KGA to GAC. Moreover, the expression of GAC was significantly increased in lung cancer and renal clear cell carcinoma [107]. More studies have shown that GAC exerts a greater effect on cell growth than KGA in cancer [108,109]. An experimental investigation demonstrated that overexpression of c-Myc inhibits miR-23, which specifically binds to the KGA 3’ UTR region, thus promoting the expression of the KGA isoform [110]. In addition, researchers have found that cleavage factor I 25 (CFIm25) can influence the alternative splicing of GLS via alternative polyadenylation, thus promoting the generation of GAC [111]. lncRNA CCAT2 reportedly acts as a scaffold, or is recruited to interact with CFIm25/CFIm68 complexes, to regulate the alternative splicing of GLS in an allele-specific manner, thus affecting the process of glutamine metabolism in cancer [112] (Figure 6B). Therefore, in addition to glycolysis, alternative splicing associated with glutamine metabolism may also be worth consideration.

Alternative splicing and immune escape

As a protective response of the body, immunity plays an important role in identifying and removing antigenic foreign bodies and maintaining a normal physiological state. However, the competition between cancer and immunity has always been a focus of attention [113-116]. Dunn et al. proposed the “immune editing” theory to describe the complex dynamic relationship between cancer and immunity [117]. Alternative splicing associated with the immune system also affects the occurrence and development of cancer.

The programmed cell death ligand 1/programmed cell death 1 (PD-L1/PD-1) immune checkpoint is a hotspot in the field of immunotherapy [118,119]. At present, PD-L1/PD-1 immunotherapy uses antibody inhibitor immune drugs to block binding between PD-1 and PD-L1. The main pattern of alternative splicing of PDCD1 is exon 3 skipping, which results in the formation of the PD-1Δ3 isoform. PD-1Δ3 is a soluble PD-1 (sPD-1) that prevents interaction between PD-L1 and PD-1. Clinical studies have demonstrated a positive correlation between prognosis and sPD-1 expression in patients with non-small cell lung cancer during erlotinib therapy [120]. Moreover, adopting an antisense oligodeoxynucleotide targeting strategy can alter the splicing pattern of PDCD-1 and guide the generation of PD-1Δ3 to exert a therapeutic effect (Figure 7A). CTLA4, another popular immune checkpoint inhibitor target, also has splicing isoforms. Soluble CTLA-4 (sCTLA-4) inhibits interaction between B7 and CD28 by binding to B7 of antigen-presenting cells, thus inhibiting the activation of T cells. Anti-sCTLA-4 monoclonal antibodies specifically bind to sCTLA-4, but do not recognize full-length CTLA-4, thereby enhancing the antigen-specific T cell response and exerting anti-tumor activity [121] (Figure 7B). Thus, it is possible to effectively enhance the efficacy of immunotherapy by using functional differences between the splicing variants of key proteins associated with immune checkpoints.

Figure 7.

Alternative splicing and immune escape. A. PDCD1 produces PD-1 and PD-1Δ3 (also known as sPD-1) isoforms via alternative splicing. Among these, sPD-1 prevents the interaction of PD-L1/PD-1. B. CTLA4 produces CTLA4 and sCTLA4 isoforms via alternative splicing, both of which reduce T cell activity. C. ST2L and sST2 originate from the alternative splicing of ST2, where sST2 inhibits the binding of ST2L/IL-1RacP heterodimer on the surface of immune cells and suppresses the activation of IL-33/ST2L signal by competitively binding to IL-33. In IL-33/ST2L signaling, compared with IRAK4-L, IRAK4-S decreases the activation potential of NF-κB. PD-1, programmed cell death-1; sPD-1, soluble PD-1; PD-L1, programmed cell death-ligand 1; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4; sCTLA-4, soluble CTLA-4; TCR, T-cell receptor; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; APC, antigen-presenting cells; IL-33, cytokine receptor interleukin-33; sST2, soluble ST2; ST2L, ST2 long isoform; IL-1RAcF, interleukin 1 receptor accessory protein; MyD88, myeloid differentiation primary response 88; IRAK-4S, IRAK-4 short isoform; IRAK-4L, IRAK-4 long isoform; IRAK-1, interleukin 1 receptor associated kinase 1; TRAF6, TNF receptor associated factor 6; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B subunit 1; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; P38, mitogen-activated protein kinase 14.

The cytokine receptor, interleukin-33 (IL-33), is an alarmin that exerts its biological effect by binding to the suppression of tumorigenicity 2 (ST2) factor. Alternative splicing of ST2 generates three isoforms: ST2L (transmembrane isoform), sST2 (soluble isoform), and ST2V [122]. When released, IL-33 activates the heterodimer ST2L/IL-1RacP (IL-1 receptor helper protein) on the surface of immune cells and induces the transcription of inflammatory genes by activating a variety of downstream cytokines and kinases. Here, sST2 usually acts as a “bait receptor” to competitively bind IL-33 and block the activation of the IL-33/ST2L signal [123,124]. Moreover, the IL-33/ST2L axis plays an important role in cancer development. Reportedly, sST2 negatively regulated IL-33/ST2L signaling in colorectal cancer and a mouse pancreatic cancer model [125,126]. In the myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia, IRAK4-L, the interleukin 1 receptor-associated kinase 4 (IRAK4) isoform, activates NF-κB via MyD88 binding. By contrast, the IRAK4-S isoform is mainly expressed in healthy hematopoietic cells, the decreased binding of which to MyD88 reduces the activation potential of NF-κB [127]; (Figure 7C). In addition, the isoforms of natural killer cell receptors, ligands, and cell adhesion molecules [128], which are reportedly generated by alternative splicing, are closely related to the occurrence and development of cancer. This indicates the usefulness of elucidating the relationship between alternative splicing and immunity.

Circular RNA (circRNA) is a special alternative splicing product

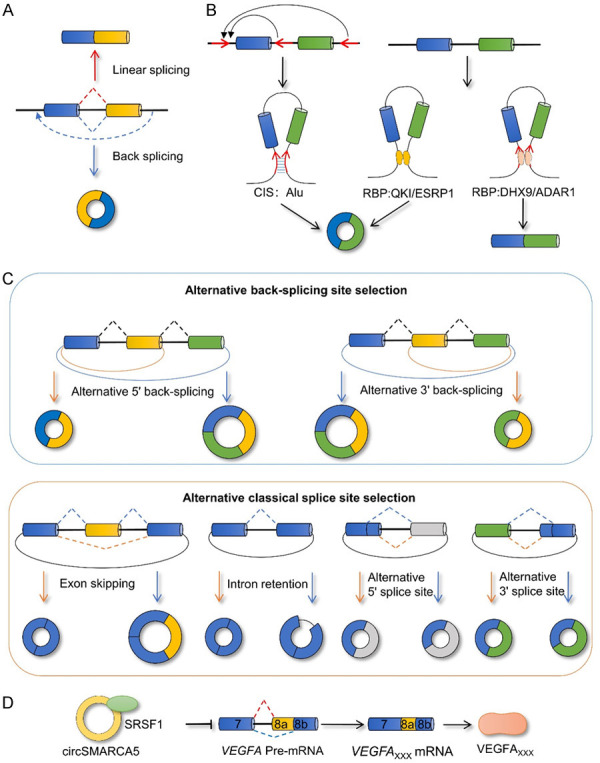

Back-splicing, a special splicing mode, is considered to compete with conventional linear splicing (Figure 8A). It involves the eventual transformation of pre-RNA into circRNA, which was initially considered to be a by-product of mis-splicing without a substantial role. However, circRNAs has increasingly attracted attention in recent years and reportedly results in either competitively binding mirRNAs as competing endogenouse RNAs, or interacting with proteins [129-135] as well as encoding small peptides to mediate its function [136-140].

Figure 8.

CircRNA is a special alternative splicing product. A. A competitive relationship exists between back-splicing and linear splicing. B. Back-splicing is affected by cis-acting elements and trans-acting factor to promote or inhibit the formation of circRNA. C. Selecting different reverse splicing sites and different conventional splicing modes will result in the generation of different circRNAs. D. CircRNA has the potential to affect the splicing pattern of SRSF1 and downstream genes. CIS, cis-acting element; RBP, RNA binding protein; ESRP1, epithelial splicing regulatory protein 1; QKI, KH domain containing RNA binding; DHX9, DExH-box helicase 9; ADAR1, adenosine deaminase 1; VEGFA, vascular endothelial growth factor A; SRSF1, serine and arginine rich splicing factor 1.

The generation of circRNAs depends on a mechanism similar to that underlying classical splicing. Although the effect of spliceosome interference on circRNA generation has been proven, the specific processes involved in its participation require further investigation [141,142]. The generation of circRNAs also depends on cis-acting elements as well as trans-acting factors involved in the splicing process [143-146]. The flanking introns of usually cyclized exons contain complementary reverse sequences; for example, Alu elements assist in back-splicing via base complementary pairing. The pairing competition between different introns or different sequences of the same intron will directly affects the selection of the back-splicing site as well as the efficacy of loop formation [147]. RNA-binding proteins also regulate the formation of circRNAs. During EMT, circRNA formation is regulated by the splicing factor QKI [146]. The YY1/p65/p300 complex stimulates QKI expression by binding to the super enhancer and the promoter of QKI to promote the formation of circRNA [148]. The splicing factor, ESRP1, promotes the formation of circUHRF1 by targeting flanking introns, thus affecting the occurrence and development of oral squamous cell carcinoma [149]. A eukaryotic initiator, elF4A3, and a transcription factor, Twist1, reportedly affect the splicing process of target genes and promote circRNA formation. However, the underlying mechanism remains unclear [150,151]. By contrast, some proteins inhibit the formation of circRNAs. Adenosine deaminase 1 (ADAR1) and DHX9 co-operatively block the formation of circRNAs by binding to the Alu element in an intron flanking the cyclized exon [152]. The androgen receptor was found to inhibit the formation of CircARSP91 by upregulating ADAR1 in hepatocellular carcinoma [153]. Thus, the regulatory mechanism of circRNA appears to be much more complex and requires further research (Figure 8B).

Notably, pre-RNA generates different circRNAs via alternative back-splicing site selection and alternative classical splicing site selection [154] (Figure 8C). Moreover, this special splicing product, circRNA, also functions as a splicing regulator to influence the alternative splicing process. In pleomorphic glioblastoma, it was initially found that the interaction between circSMARCA5 and SRSF1 regulates the alternative splicing of VEGFA [91,143] (Figure 8D). In addition, although circUBR5 does not display a functional phenotype associated with non-small cell lung cancer, evidence indicates that it binds to splicing factors, NOVA1, QKI, and U1 snRNA, in the nucleus. This suggests that circUBR5 may play the role of a snRNA in the spliceosome [155]. Thus, investigating the mechanism by which circRNAs serve as a special splicing product or splicing factor may lead to a better understanding of their role in cancer.

Alternative splicing and therapy

Tumorigenesis is often accompanied by alterations in alternative splicing. This suggests that the expression levels of cancer-related isoforms depend on the mechanism of alternative splicing. Therefore, cancer therapy approaches which focus on alternative splicing of RNA represent an emerging strategy that may eliminate cancer-associated transcript variants and protein isoform production at the source. Currently, alternative splicing therapy strategies are divided into three categories: (i) cis-acting element strategy; (ii) trans-acting factor strategy; and (iii) splice-switching oligonucleotide therapy.

Over the past two decades, researchers have studied the functional mechanisms and medical effects of natural products in a variety of microbes [156]. First, natural compounds, such as Herboxidiene [157,158], FR901464 [159,160], and Pladienolides [161-163], were identified in Pseudomonas spp. and Streptomyces spp. These regulate spliceosomal function by targeting SF3B1, an important component of spliceosomal U2snRNP. The discovery of natural products has paved the way for the subsequent development of chemical compounds that target the splicing process and are more stable and soluble than wild-type compounds as well. For example, spliceostatin A (SSA) prevents SF3B1 from interacting with pre-RNA and also prevents U2snRNA from interacting with branching site sequences, thus inducing changes in alternative splicing [164,165]. In addition, the pladienolide analogue, E7107, which induces splicing damage by targeting SF3B1, exerts significant antitumor activity, as demonstrated by a phase I clinical trial in 2006. It was also the first splice-related small molecule regulator to be considered as clinically useful, but suspended due to complex synthesis and toxicity issues [166,167]. Although resolving these issues remains a challenging task, the development as well as clinical testing of these drugs may provide new insights into cancer treatment and create therapeutic opportunities.

In addition, splicing regulatory proteins also act as anti-tumor targets. SR proteins regulate subcellular localization and interaction with pre-RNA via phosphorylation/dephosphorylation during the alternative splicing process. At present, many SR kinases, such as SRPK1, Clk/Sty kinase, and topoisomerase, have been identified, and many anti-tumor drugs, such as, NB-506 [168], SRPIN340 which targets SRPK1 [169], and the benzothiazole compound, TG003 [170], an inhibitor of Clk/Sty kinase activity, are known to indirectly alter the splice pattern of genes in response to SR kinases. Although, the screening of multiple compounds has confirmed that indole derivatives target SR proteins to regulate the splicing process, the specific mechanism of action involved needs further clarification [171]. Thus, pharmacological inhibition of SR kinases may be considered as a novel therapeutic strategy.

In addition, splice-switching oligonucleotide therapy has attracted much attention in recent years. Oligonucleotides, usually composed of 18 to 30 nucleotide sequences, bind to pre-RNA using the principle of complementary base pairing, leading to steric hindrance, which prevents the splicing regulator from interacting with the pre-RNA. This results in a change in the original splicing design, ultimately regulating the production of target proteins by restoring or closing its open reading frame, or isoform conversion [172,173]. Splice-related oligonucleotides typically target specific sequence elements of pre-RNA, such as the 5’ splice site, 3’ splice site, and BS. Oligonucleotides designed for these sites vary in their ability to alter splicing [174,175]. In recent years, many studies have used splice-switch oligonucleotide therapy to alter the expression of cancer-associated splice isoforms [176-180]. In addition to designing oligonucleotides that target sequence elements, researchers have attempted to regulate the alternative splicing process by inhibiting the activity of splicing factors, such as PTBP1, SRSF1, or RBFOX1/2, via oligonucleotides. However, interference by splicing factors affects alternative splicing extensively, and thus the toxicity caused by the inhibition of splicing factors must be resolved [181]. Currently, the splice-switching oligonucleotide therapy is at the clinical stage. The approved spinal muscular atrophy drug, Spinraza™/Nusinersen, is an antisense oligonucleotide that promotes exon 7 inclusion by targeting the ISS [182]. The most advanced therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy also aims to restore the reading framework for dystrophin translation using oligonucleotide spliceotomy correction [183]. These results also provide a clinical basis for the development of cancer-associated splice-switching oligonucleotide therapy.

Conclusions and perspectives

Although alternative splicing in eukaryotes was discovered in the 1980s [184], only a few early studies have attempted to investigate this process. In fact, alternative splicing did not receive much attention until recently, when multiple studies found that new products produced via the alternative splicing displayed different biological functions in various physiological and pathological processes. Especially, cancer cells in the pathological state take advantage of the selectivity of splicing sites to produce cancer-related splicing variants that serve their purpose, resulting in the dysregulation of the entire alternative splicing process. This reinforces the importance of conducting an extensive investigation into splicing transcripts. Advanced sequencing technologies are beneficial to promote progress in cancer research [185-189]. And they can help visualize the full picture of alternative splicing events across the genome and even enable the discovery of splice-derived peptides that are candidate neoantigens, a great addition to immunotherapy [190,191]. Many tools, such as McSplicer [192], SplicingViewer [193], SpliceSeq [194], PennDiff [195], MATS [196], rMATS [197], and SplicingCompass [198], facilitate the detection and visualization of splicing events. Alternative splicing tools have also been developed by The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) to understand clinical subtype differences, such as TSVdb [199] and TCGA SpliceSeq [200]. In addition, a cancer-specific circRNA splicing tool was developed recently [201]. Therefore, sequencing technology becomes a important tool to identify potential cancer-related splicing isoforms and is expected to provide effective cancer markers that facilitate clinical diagnoses, which pose a major challenge to the application of the sequencing technology.

Alternative splicing is a key link in the flow of genetic information from DNA to proteins, indicating that it is a dynamic process regulated by multiple factors. Therefore, in the study of cancer-related splicing, it is not possible to simply attribute abnormal regulation of pre-RNA to specific elements and splicing factors. A far more comprehensive understanding of the regulatory processes involved in alternative splicing is required. Starting from the coupling process of splicing and transcription, a complex relationship is established between splicing, chromatin, and transcription. Chromatin conformation, histone modification, DNA methylation, and Pol II extension are closely related to the regulation of alternative splicing. RNA modification, especially m6A, reportedly regulates alternative splicing by methylating the sequence and recruiting binding proteins. However, the general role of RNA modification in alternative splicing requires further clarification. In addition, numerous studies have shown that non-coding RNAs play a key role in cancer [202-213]. And non-coding RNAs are also the important splicing regulators, which can change splicing results by interfering with the generation, posttranslational modification and intracellular distribution of splicing factors [214-217]. However, the relationship between alternative splicing and non-coding RNAs is not a simple regulated affiliation. CircRNA generation relies on a nonclassical splicing pathway termed “back-splicing”, which plays an important role in cancer development. Current research indicates that back-splicing may compete with conventional splicing modes. However, the mechanism of back-splicing is still poorly understood, and it is obvious that more studies pertaining to the mechanisms involved in back-splicing are needed to better understand the generation and function of circRNAs.

The ultimate objective of our research into alternative splicing mechanisms was to identify potential therapeutic targets for clinical application and provide better treatment strategies to patients. Alternative splicing affects the development of cancer cells via a variety of physiological processes, indicating that these cancer-related isoforms and various regulatory factors may be used as potential targets in cancer therapy. Currently, the development of splicing-related drugs is still in the development stages. Highly anticipated splice-switching oligonucleotide therapy also encounters issues involving in vivo delivery barriers, where the need to further optimize the process of cellular uptake of oligonucleotide drugs via chemical modification poses a major challenge to the development of personalized therapy.

In this review, we clarified mechanisms underlying the RNA splicing process as well as important factors influencing alternative splicing. By listing various cancer-related isoforms, we revealed that abnormal splicing affects various aspects of cancer characteristics. Furthermore, we discussed classic splicing patterns, circRNA back-splicing, and the prospects of alternative splicing in clinical treatment. These suggest that alternative splicing is a key link that cannot be ignored in the process of cancer development and that its complex and fine regulatory mechanisms as well as significant clinical value are worth further exploration.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported partially by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U20A20367, 82073135, 82072374, 82003243, 82002239, 81972776, 81803025), the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2021JJ30897, 2021JJ31127, 2021JJ41043, 2020JJ4766, 2020JJ4125), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central South University (2021zzts0922).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Lee Y, Rio DC. Mechanisms and regulation of alternative Pre-mRNA splicing. Annu Rev Biochem. 2015;84:291–323. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-034316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang ET, Sandberg R, Luo S, Khrebtukova I, Zhang L, Mayr C, Kingsmore SF, Schroth GP, Burge CB. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature. 2008;456:470–476. doi: 10.1038/nature07509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sionov RV, Vlahopoulos SA, Granot Z. Regulation of Bim in health and disease. Oncotarget. 2015;6:23058–23134. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.He C, Zhou F, Zuo Z, Cheng H, Zhou R. A global view of cancer-specific transcript variants by subtractive transcriptome-wide analysis. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4732. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galej WP, Nguyen TH, Newman AJ, Nagai K. Structural studies of the spliceosome: zooming into the heart of the machine. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2014;25:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bourgeois CF, Lejeune F, Stévenin J. Broad specificity of SR (serine/arginine) proteins in the regulation of alternative splicing of pre-messenger RNA. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2004;78:37–88. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(04)78002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Busch A, Hertel KJ. Evolution of SR protein and hnRNP splicing regulatory factors. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2012;3:1–12. doi: 10.1002/wrna.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huelga SC, Vu AQ, Arnold JD, Liang TY, Liu PP, Yan BY, Donohue JP, Shiue L, Hoon S, Brenner S, Ares M Jr, Yeo GW. Integrative genome-wide analysis reveals cooperative regulation of alternative splicing by hnRNP proteins. Cell Rep. 2012;1:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pandya-Jones A, Black DL. Co-transcriptional splicing of constitutive and alternative exons. RNA. 2009;15:1896–1908. doi: 10.1261/rna.1714509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tennyson CN, Klamut HJ, Worton RG. The human dystrophin gene requires 16 hours to be transcribed and is cotranscriptionally spliced. Nat Genet. 1995;9:184–190. doi: 10.1038/ng0295-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Listerman I, Sapra AK, Neugebauer KM. Cotranscriptional coupling of splicing factor recruitment and precursor messenger RNA splicing in mammalian cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:815–822. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Custódio N, Carmo-Fonseca M. Co-transcriptional splicing and the CTD code. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2016;51:395–411. doi: 10.1080/10409238.2016.1230086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naftelberg S, Schor IE, Ast G, Kornblihtt AR. Regulation of alternative splicing through coupling with transcription and chromatin structure. Annu Rev Biochem. 2015;84:165–198. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-034242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bondarenko VA, Steele LM, Ujvári A, Gaykalova DA, Kulaeva OI, Polikanov YS, Luse DS, Studitsky VM. Nucleosomes can form a polar barrier to transcript elongation by RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell. 2006;24:469–479. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luco RF, Pan Q, Tominaga K, Blencowe BJ, Pereira-Smith OM, Misteli T. Regulation of alternative splicing by histone modifications. Science. 2010;327:996–1000. doi: 10.1126/science.1184208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan F, Zhao M, Xiong F, Wang Y, Zhang S, Gong Z, Li X, He Y, Shi L, Wang F, Xiang B, Zhou M, Li X, Li Y, Li G, Zeng Z, Xiong W, Guo C. N6-methyladenosine-dependent signalling in cancer progression and insights into cancer therapies. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2021;40:146. doi: 10.1186/s13046-021-01952-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng Z, Li Q, Meng R, Yi B, Xu Q. METTL3 regulates alternative splicing of MyD88 upon the lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response in human dental pulp cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22:2558–2568. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tian C, Huang Y, Li Q, Feng Z, Xu Q. Mettl3 regulates osteogenic differentiation and alternative splicing of Vegfa in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:551. doi: 10.3390/ijms20030551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dominissini D, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Schwartz S, Salmon-Divon M, Ungar L, Osenberg S, Cesarkas K, Jacob-Hirsch J, Amariglio N, Kupiec M, Sorek R, Rechavi G. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature. 2012;485:201–206. doi: 10.1038/nature11112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pendleton KE, Chen B, Liu K, Hunter OV, Xie Y, Tu BP, Conrad NK. The U6 snRNA m(6)A methyltransferase METTL16 regulates SAM synthetase intron retention. Cell. 2017;169:824–835. e814. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiao W, Adhikari S, Dahal U, Chen YS, Hao YJ, Sun BF, Sun HY, Li A, Ping XL, Lai WY, Wang X, Ma HL, Huang CM, Yang Y, Huang N, Jiang GB, Wang HL, Zhou Q, Wang XJ, Zhao YL, Yang YG. Nuclear m(6)A reader YTHDC1 regulates mRNA splicing. Mol Cell. 2016;61:507–519. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roundtree IA, He C. Nuclear m(6)A reader YTHDC1 regulates mRNA splicing. Trends Genet. 2016;32:320–321. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alarcón CR, Goodarzi H, Lee H, Liu X, Tavazoie S, Tavazoie SF. HNRNPA2B1 is a mediator of m(6)A-dependent nuclear RNA processing events. Cell. 2015;162:1299–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou KI, Shi H, Lyu R, Wylder AC, Matuszek Ż, Pan JN, He C, Parisien M, Pan T. Regulation of co-transcriptional pre-mRNA splicing by m(6)A through the low-complexity protein hnRNPG. Mol Cell. 2019;76:70–81. e79. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bartosovic M, Molares HC, Gregorova P, Hrossova D, Kudla G, Vanacova S. N6-methyladenosine demethylase FTO targets pre-mRNAs and regulates alternative splicing and 3’-end processing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:11356–11370. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Betticher DC, Thatcher N, Altermatt HJ, Hoban P, Ryder WD, Heighway J. Alternate splicing produces a novel cyclin D1 transcript. Oncogene. 1995;11:1005–1011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paronetto MP, Cappellari M, Busà R, Pedrotti S, Vitali R, Comstock C, Hyslop T, Knudsen KE, Sette C. Alternative splicing of the cyclin D1 proto-oncogene is regulated by the RNA-binding protein Sam68. Cancer Res. 2010;70:229–239. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olshavsky NA, Comstock CE, Schiewer MJ, Augello MA, Hyslop T, Sette C, Zhang J, Parysek LM, Knudsen KE. Identification of ASF/SF2 as a critical, allele-specific effector of the cyclin D1b oncogene. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3975–3984. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Comstock CE, Augello MA, Benito RP, Karch J, Tran TH, Utama FE, Tindall EA, Wang Y, Burd CJ, Groh EM, Hoang HN, Giles GG, Severi G, Hayes VM, Henderson BE, Le Marchand L, Kolonel LN, Haiman CA, Baffa R, Gomella LG, Knudsen ES, Rui H, Henshall SM, Sutherland RL, Knudsen KE. Cyclin D1 splice variants: polymorphism, risk, and isoform-specific regulation in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5338–5349. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y, Dean JL, Millar EK, Tran TH, McNeil CM, Burd CJ, Henshall SM, Utama FE, Witkiewicz A, Rui H, Sutherland RL, Knudsen KE, Knudsen ES. Cyclin D1b is aberrantly regulated in response to therapeutic challenge and promotes resistance to estrogen antagonists. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5628–5638. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Solomon DA, Wang Y, Fox SR, Lambeck TC, Giesting S, Lan Z, Senderowicz AM, Conti CJ, Knudsen ES. Cyclin D1 splice variants. Differential effects on localization, RB phosphorylation, and cellular transformation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:30339–30347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303969200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Millar EK, Dean JL, McNeil CM, O’Toole SA, Henshall SM, Tran T, Lin J, Quong A, Comstock CE, Witkiewicz A, Musgrove EA, Rui H, Lemarchand L, Setiawan VW, Haiman CA, Knudsen KE, Sutherland RL, Knudsen ES. Cyclin D1b protein expression in breast cancer is independent of cyclin D1a and associated with poor disease outcome. Oncogene. 2009;28:1812–1820. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu J, Sen S, Wei C, Frazier ML. Cyclin D1b represses breast cancer cell growth by antagonizing the action of cyclin D1a on estrogen receptor alpha-mediated transcription. Int J Oncol. 2010;36:39–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matter N, Herrlich P, König H. Signal-dependent regulation of splicing via phosphorylation of Sam68. Nature. 2002;420:691–695. doi: 10.1038/nature01153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Batsché E, Yaniv M, Muchardt C. The human SWI/SNF subunit Brm is a regulator of alternative splicing. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:22–29. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cappellari M, Bielli P, Paronetto MP, Ciccosanti F, Fimia GM, Saarikettu J, Silvennoinen O, Sette C. The transcriptional co-activator SND1 is a novel regulator of alternative splicing in prostate cancer cells. Oncogene. 2014;33:3794–3802. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng C, Yaffe MB, Sharp PA. A positive feedback loop couples Ras activation and CD44 alternative splicing. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1715–1720. doi: 10.1101/gad.1430906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang H, Zhou M, Shi B, Zhang Q, Jiang H, Sun Y, Liu J, Zhou K, Yao M, Gu J, Yang S, Mao Y, Li Z. Identification of an exon 4-deletion variant of epidermal growth factor receptor with increased metastasis-promoting capacity. Neoplasia. 2011;13:461–471. doi: 10.1593/neo.101744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu X, Peled N, Greer J, Wu W, Choi P, Berger AH, Wong S, Jen KY, Seo Y, Hann B, Brooks A, Meyerson M, Collisson EA. MET Exon 14 mutation encodes an actionable therapeutic target in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2017;77:4498–4505. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gautrey H, Jackson C, Dittrich AL, Browell D, Lennard T, Tyson-Capper A. SRSF3 and hnRNP H1 regulate a splicing hotspot of HER2 in breast cancer cells. RNA Biol. 2015;12:1139–1151. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2015.1076610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boise LH, González-García M, Postema CE, Ding L, Lindsten T, Turka LA, Mao X, Nuñez G, Thompson CB. bcl-x, a bcl-2-related gene that functions as a dominant regulator of apoptotic cell death. Cell. 1993;74:597–608. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90508-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwerk C, Schulze-Osthoff K. Regulation of apoptosis by alternative pre-mRNA splicing. Mol Cell. 2005;19:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stevens M, Oltean S. Modulation of the apoptosis gene Bcl-x function through alternative splicing. Front Genet. 2019;10:804. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paronetto MP, Achsel T, Massiello A, Chalfant CE, Sette C. The RNA-binding protein Sam68 modulates the alternative splicing of Bcl-x. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:929–939. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200701005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bielli P, Bordi M, Di Biasio V, Sette C. Regulation of BCL-X splicing reveals a role for the polypyrimidine tract binding protein (PTBP1/hnRNP I) in alternative 5’ splice site selection. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:12070–12081. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cloutier P, Toutant J, Shkreta L, Goekjian S, Revil T, Chabot B. Antagonistic effects of the SRp30c protein and cryptic 5’ splice sites on the alternative splicing of the apoptotic regulator Bcl-x. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21315–21324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800353200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garneau D, Revil T, Fisette JF, Chabot B. Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein F/H proteins modulate the alternative splicing of the apoptotic mediator Bcl-x. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22641–22650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501070200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen ZY, Cai L, Zhu J, Chen M, Chen J, Li ZH, Liu XD, Wang SG, Bie P, Jiang P, Dong JH, Li XW. Fyn requires HnRNPA2B1 and Sam68 to synergistically regulate apoptosis in pancreatic cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:1419–1426. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh R, Gupta SC, Peng WX, Zhou N, Pochampally R, Atfi A, Watabe K, Lu Z, Mo YY. Regulation of alternative splicing of Bcl-x by BC200 contributes to breast cancer pathogenesis. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2262. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zong L, Hattori N, Yasukawa Y, Kimura K, Mori A, Seto Y, Ushijima T. LINC00162 confers sensitivity to 5-Aza-2’-deoxycytidine via modulation of an RNA splicing protein, HNRNPH1. Oncogene. 2019;38:5281–5293. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-0792-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pospiech N, Cibis H, Dietrich L, Müller F, Bange T, Hennig S. Identification of novel PANDAR protein interaction partners involved in splicing regulation. Sci Rep. 2018;8:2798. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21105-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bielli P, Busà R, Di Stasi SM, Munoz MJ, Botti F, Kornblihtt AR, Sette C. The transcription factor FBI-1 inhibits SAM68-mediated BCL-X alternative splicing and apoptosis. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:419–427. doi: 10.1002/embr.201338241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cheng J, Zhou T, Liu C, Shapiro JP, Brauer MJ, Kiefer MC, Barr PJ, Mountz JD. Protection from Fas-mediated apoptosis by a soluble form of the Fas molecule. Science. 1994;263:1759–1762. doi: 10.1126/science.7510905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Izquierdo JM. Heterogeneous ribonucleoprotein C displays a repressor activity mediated by T-cell intracellular antigen-1-related/like protein to modulate Fas exon 6 splicing through a mechanism involving Hu antigen R. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:8001–8014. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jang HN, Liu Y, Choi N, Oh J, Ha J, Zheng X, Shen H. Binding of SRSF4 to a novel enhancer modulates splicing of exon 6 of Fas pre-mRNA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;506:703–708. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.10.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu Y, Conaway L, Rutherford Bethard J, Al-Ayoubi AM, Thompson Bradley A, Zheng H, Weed SA, Eblen ST. Phosphorylation of the alternative mRNA splicing factor 45 (SPF45) by Clk1 regulates its splice site utilization, cell migration and invasion. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:4949–4962. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Paronetto MP, Bernardis I, Volpe E, Bechara E, Sebestyén E, Eyras E, Valcárcel J. Regulation of FAS exon definition and apoptosis by the Ewing sarcoma protein. Cell Rep. 2014;7:1211–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.03.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peciuliene I, Vilys L, Jakubauskiene E, Zaliauskiene L, Kanopka A. Hypoxia alters splicing of the cancer associated Fas gene. Exp Cell Res. 2019;380:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2019.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Villamizar O, Chambers CB, Riberdy JM, Persons DA, Wilber A. Long noncoding RNA Saf and splicing factor 45 increase soluble Fas and resistance to apoptosis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:13810–13826. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sehgal L, Mathur R, Braun FK, Wise JF, Berkova Z, Neelapu S, Kwak LW, Samaniego F. FAS-antisense 1 lncRNA and production of soluble versus membrane Fas in B-cell lymphoma. Leukemia. 2014;28:2376–2387. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hou X, Tang L, Li X, Xiong F, Mo Y, Jiang X, Deng X, Peng M, Wu P, Zhao M, Ouyang J, Shi L, He Y, Yan Q, Zhang S, Gong Z, Li G, Zeng Z, Wang F, Guo C, Xiong W. Potassium channel protein KCNK6 promotes breast cancer cell proliferation, invasion, and migration. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:616784. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.616784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhong Y, Yang L, Xiong F, He Y, Tang Y, Shi L, Fan S, Li Z, Zhang S, Gong Z, Guo C, Liao Q, Zhou Y, Zhou M, Xiang B, Li X, Li Y, Zeng Z, Li G, Xiong W. Long non-coding RNA AFAP1-AS1 accelerates lung cancer cells migration and invasion by interacting with SNIP1 to upregulate c-Myc. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:240. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00562-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang M, Dai M, Wang D, Tang T, Xiong F, Xiang B, Zhou M, Li X, Li Y, Xiong W, Li G, Zeng Z, Guo C. The long noncoding RNA AATBC promotes breast cancer migration and invasion by interacting with YBX1 and activating the YAP1/Hippo signaling pathway. Cancer Lett. 2021;512:60–72. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2021.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wu Y, Wang D, Wei F, Xiong F, Zhang S, Gong Z, Shi L, Li X, Xiang B, Ma J, Deng H, He Y, Liao Q, Zhang W, Li X, Li Y, Guo C, Zeng Z, Li G, Xiong W. EBV-miR-BART12 accelerates migration and invasion in EBV-associated cancer cells by targeting tubulin polymerization-promoting protein 1. FASEB J. 2020;34:16205–16223. doi: 10.1096/fj.202001508R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tang T, Yang L, Cao Y, Wang M, Zhang S, Gong Z, Xiong F, He Y, Zhou Y, Liao Q, Xiang B, Zhou M, Guo C, Li X, Li Y, Xiong W, Li G, Zeng Z. LncRNA AATBC regulates Pinin to promote metastasis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Mol Oncol. 2020;14:2251–2270. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fan C, Tu C, Qi P, Guo C, Xiang B, Zhou M, Li X, Wu X, Li X, Li G, Xiong W, Zeng Z. GPC6 promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Cancer. 2019;10:3926–3932. doi: 10.7150/jca.31345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhu K, Li P, Mo Y, Wang J, Jiang X, Ge J, Huang W, Liu Y, Tang Y, Gong Z, Liao Q, Li X, Li G, Xiong W, Zeng Z, Yu J. Neutrophils: accomplices in metastasis. Cancer Lett. 2020;492:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2020.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fan C, Tang Y, Wang J, Wang Y, Xiong F, Zhang S, Li X, Xiang B, Wu X, Guo C, Ma J, Zhou M, Li X, Xiong W, Li Y, Li G, Zeng Z. Long non-coding RNA LOC284454 promotes migration and invasion of nasopharyngeal carcinoma via modulating the Rho/Rac signaling pathway. Carcinogenesis. 2019;40:380–391. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgy143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Talmadge JE, Fidler IJ. AACR centennial series: the biology of cancer metastasis: historical perspective. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5649–5669. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Miwa T, Nagata T, Kojima H, Sekine S, Okumura T. Isoform switch of CD44 induces different chemotactic and tumorigenic ability in gallbladder cancer. Int J Oncol. 2017;51:771–780. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2017.4063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brown RL, Reinke LM, Damerow MS, Perez D, Chodosh LA, Yang J, Cheng C. CD44 splice isoform switching in human and mouse epithelium is essential for epithelial-mesenchymal transition and breast cancer progression. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:1064–1074. doi: 10.1172/JCI44540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Torre C, Wang SJ, Xia W, Bourguignon LY. Reduction of hyaluronan-CD44-mediated growth, migration, and cisplatin resistance in head and neck cancer due to inhibition of Rho kinase and PI-3 kinase signaling. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;136:493–501. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2010.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bhattacharya R, Mitra T, Ray Chaudhuri S, Roy SS. Mesenchymal splice isoform of CD44 (CD44s) promotes EMT/invasion and imparts stem-like properties to ovarian cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:3373–3383. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li L, Qi L, Qu T, Liu C, Cao L, Huang Q, Song W, Yang L, Qi H, Wang Y, Gao B, Guo Y, Sun B, Meng B, Zhang B, Cao W. Epithelial splicing regulatory protein 1 inhibits the invasion and metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2018;188:1882–1894. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2018.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen L, Yao Y, Sun L, Zhou J, Miao M, Luo S, Deng G, Li J, Wang J, Tang J. Snail driving alternative splicing of CD44 by ESRP1 enhances invasion and migration in epithelial ovarian cancer. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;43:2489–2504. doi: 10.1159/000484458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wu G, Li Z, Jiang P, Zhang X, Xu Y, Chen K, Li X. MicroRNA-23a promotes pancreatic cancer metastasis by targeting epithelial splicing regulator protein 1. Oncotarget. 2017;8:82854–82871. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu S, Cheng C. Akt signaling is sustained by a CD44 splice isoform-mediated positive feedback loop. Cancer Res. 2017;77:3791–3801. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ghigna C, Giordano S, Shen H, Benvenuto F, Castiglioni F, Comoglio PM, Green MR, Riva S, Biamonti G. Cell motility is controlled by SF2/ASF through alternative splicing of the Ron protooncogene. Mol Cell. 2005;20:881–890. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Biamonti G, Bonomi S, Gallo S, Ghigna C. Making alternative splicing decisions during epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:2515–2526. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-0931-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bonomi S, di Matteo A, Buratti E, Cabianca DS, Baralle FE, Ghigna C, Biamonti G. HnRNP A1 controls a splicing regulatory circuit promoting mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:8665–8679. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Golan-Gerstl R, Cohen M, Shilo A, Suh SS, Bakàcs A, Coppola L, Karni R. Splicing factor hnRNP A2/B1 regulates tumor suppressor gene splicing and is an oncogenic driver in glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2011;71:4464–4472. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lefave CV, Squatrito M, Vorlova S, Rocco GL, Brennan CW, Holland EC, Pan YX, Cartegni L. Splicing factor hnRNPH drives an oncogenic splicing switch in gliomas. EMBO J. 2011;30:4084–4097. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Huang GW, Zhang YL, Liao LD, Li EM, Xu LY. Natural antisense transcript TPM1-AS regulates the alternative splicing of tropomyosin I through an interaction with RNA-binding motif protein 4. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2017;90:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2017.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Grelet S, Link LA, Howley B, Obellianne C, Palanisamy V, Gangaraju VK, Diehl JA, Howe PH. A regulated PNUTS mRNA to lncRNA splice switch mediates EMT and tumour progression. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19:1105–1115. doi: 10.1038/ncb3595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wei X, Chen Y, Jiang X, Peng M, Liu Y, Mo Y, Ren D, Hua Y, Yu B, Zhou Y, Liao Q, Wang H, Xiang B, Zhou M, Li X, Li G, Li Y, Xiong W, Zeng Z. Mechanisms of vasculogenic mimicry in hypoxic tumor microenvironments. Mol Cancer. 2021;20:7. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-01288-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jiang X, Wang J, Deng X, Xiong F, Zhang S, Gong Z, Li X, Cao K, Deng H, He Y, Liao Q, Xiang B, Zhou M, Guo C, Zeng Z, Li G, Li X, Xiong W. The role of microenvironment in tumor angiogenesis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2020;39:204. doi: 10.1186/s13046-020-01709-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Biselli-Chicote PM, Oliveira AR, Pavarino EC, Goloni-Bertollo EM. VEGF gene alternative splicing: pro- and anti-angiogenic isoforms in cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138:363–370. doi: 10.1007/s00432-011-1073-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Amin EM, Oltean S, Hua J, Gammons MV, Hamdollah-Zadeh M, Welsh GI, Cheung MK, Ni L, Kase S, Rennel ES, Symonds KE, Nowak DG, Royer-Pokora B, Saleem MA, Hagiwara M, Schumacher VA, Harper SJ, Hinton DR, Bates DO, Ladomery MR. WT1 mutants reveal SRPK1 to be a downstream angiogenesis target by altering VEGF splicing. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:768–780. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]