Abstract

We evaluated 1,010 Salmonella isolates classified as fluoroquinolone susceptible according to the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards guidelines for susceptibility to nalidixic acid and three fluoroquinolones. These isolates were divided into two distinct subpopulations, with the great majority (n = 960) being fully ciprofloxacin susceptible and a minority (n = 50) exhibiting reduced ciprofloxacin susceptibility (MICs ranging between 0.125 and 0.5 μg/ml). The less ciprofloxacin-susceptible isolates were uniformly resistant to nalidixic acid, while only 12 (1.3%) of the fully susceptible isolates were nalidixic acid resistant. A similar association was observed between resistance to nalidixic acid and decreased susceptibility to ofloxacin or norfloxacin. A mutation of the gyrA gene could be demonstrated in all isolates for which the ciprofloxacin MICs were ≥0.125 μg/ml and in 94% of the nalidixic acid-resistant isolates but in none of the nalidixic acid-susceptible isolates analyzed. Identification of nalidixic acid resistance by the disk diffusion method provided a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 87.3% as tools to screen for isolates for which the MICs of ciprofloxacin were ≥0.125 μg/ml. We regard it as important that microbiology laboratories endeavor to recognize these less susceptible Salmonella strains, in order to reveal their clinical importance and to survey their epidemic spread.

Fluoroquinolones have a good in vitro and clinical activity against isolates of the Salmonella species (1). Yet, during the last years several treatment failures with ciprofloxacin and other fluoroquinolones have been reported both in immunocompromised patients and in those with normal host defense (2, 10, 11, 13, 18, 19, 21, 24, 26, 27). According to the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) guidelines, which use the MICs of ≤1 and ≥4 μg/ml as respective breakpoints for susceptibility and resistance (15), these infections have been caused by ciprofloxacin-susceptible isolates. The majority of cases have involved Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi (hereafter Salmonella serovar Typhi) infections (10, 11, 24) and invasive infections with nontyphoidal salmonellas caused by strains which initially have been fully susceptible to ciprofloxacin with MICs of ≤0.064 μg/ml (2, 18, 19, 21, 26). After fluoroquinolone treatment failure, however, the ciprofloxacin MICs for these strains were ≥0.125 μg/ml.

Single point mutation in the quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) of the topoisomerase gene gyrA (amino acids 67 to 122) in salmonellas usually leads simultaneously to resistance against nalidixic acid, a nonfluorinated narrow-spectrum quinolone, and to decreased ciprofloxacin susceptibility (18, 22). It has been suggested that resistance to nalidixic acid may be an indicator of low-level resistance to ciprofloxacin (10, 14, 26). During our previous study focusing on the susceptibility of salmonellas to fluoroquinolones (7), we observed that the strain collection defined as susceptible according to the NCCLS guidelines could be divided into two subpopulations, one fully susceptible and the other with reduced susceptibility. The purpose of the present study was to confirm this finding in a large collection of Salmonella isolates and to illustrate the phenomenon by using scattergram analysis. In addition, we aimed at assessing whether resistance to nalidixic acid could be used to screen for decreased fluoroquinolone susceptibility in salmonellas. In doing so, we compared the susceptibilities of 1,010 epidemiologically unrelated Salmonella isolates to nalidixic acid and three fluoroquinolones.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Salmonella isolates and susceptibility testing.

We included in this study a total of 1,010 clinical Salmonella isolates collected in Finland between 1995 and 1998. Of these isolates, 810 were collected in three different phases yearly from 1995 to 1997 (7) and 200 were collected in one phase in 1998. All isolates were considered to be epidemiologically unrelated based on their recovery from distinct sources. For each Salmonella outbreak recognized, only one isolate representing the epidemic strain was included. The Salmonella collection consisted of 83 different serotypes. The most prevalent serotypes were Salmonella serovar Enteritidis and Salmonella serovar Typhimurium, accounting for 27 and 25% of the isolates, respectively. The study collection contained three Salmonella serovar Paratyphi B and no Salmonella serovar Typhi isolates.

The MICs for the isolates were determined by the standard agar plate dilution method according to the NCCLS guidelines (15). Mueller-Hinton II agar (BBL, Becton Dickinson and Company, Cockeysville, Md.) was used as the culture medium. The antimicrobials evaluated were ciprofloxacin (MIC range, 0.008 to 16 μg/ml), ofloxacin (MIC range, 0.008 to 16 μg/ml), norfloxacin (MIC range, 0.008 to 32 μg/ml), and nalidixic acid (MIC range, 2 to 128 μg/ml). Disk diffusion tests were performed according to the NCCLS guidelines (16) for all isolates found to be nalidixic acid resistant (MIC, ≥32 μg/ml) and for an equal number of randomly selected nalidixic acid-susceptible isolates. The antimicrobials evaluated were nalidixic acid (disk content, 30 μg), ciprofloxacin (disk content, 5 and 10 μg), ofloxacin (disk content, 5 μg), and norfloxacin (disk content, 5 and 10 μg). Antimicrobial disks were purchased from Oxoid Ltd. (Sollentuna, Sweden). Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213, Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, E. coli ATCC 35218, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 were used as controls in susceptibility testing.

PCR and sequencing.

The QRDR of the gyrA gene was sequenced from all isolates found to be nalidixic acid resistant and from a number of nalidixic acid-susceptible isolates selected based on variable disk zone diameters and ciprofloxacin MICs. Chromosomal DNA was prepared from each strain by boiling for 10 min and proteinase K digestion. The four oligonucleotide primers used in the PCR amplification and DNA sequencing of the gyrA gene fragments were as described by Ouabdesselam et al. (18). Oligonucleotides were synthesized by Eurogentec (Herstal, Belgique). The final volume of each PCR mixture was 50 μl, and the mixtures contained 2 U of DyNAzyme DNA polymerase, 1× PCR buffer (Finnzymes, Espoo, Finland), 0.01 μmol of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 20 pmol of each primer, and 5 μl of the template. PCR amplifications were performed in an automated thermal cycler, the DNA Engine PTC-200 (MJ Research, Inc., Watertown, Mass.), with 30 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, annealing at 54°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 2 min, followed by a final step with extension at 72°C for 5 min. Primers and free nucleotides were removed with the High Pure PCR Product Purification Kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Sequencing was performed with the ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit with AmpliTaq DNA Polymerase, FS (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.), and analyzed in an automatic DNA sequencer, ABI PRISM 377 DNA Sequencer (PE Applied Biosystems). The gyrA fragments of all mutated and five wild-type strains were sequenced in both directions.

Data analysis.

The susceptibility data were analyzed by using the WHONET4 computer program, available from J. Stelling (WHO/EMC, Geneva, Switzerland). The nucleotide sequence data were assembled and edited by using SeqEd software version 1.0.3 (PE Applied Biosystems) and GCG program package version 10.0 (Genetics Computer Group, Madison, Wis.), and the sequences were compared with the published section of the sequence of the Salmonella serovar Typhimurium gyrA gene (6). Statistical analysis was done with the independent sample t test and the Mann-Whitney U test. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Correlation between MICs of fluoroquinolones and nalidixic acid.

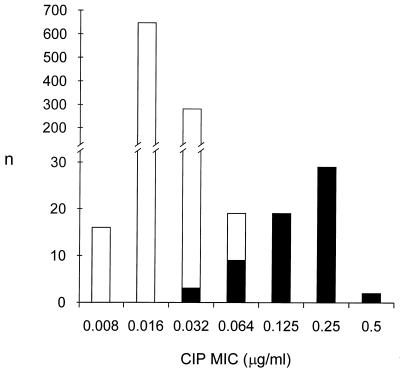

All 1,010 Salmonella isolates were classified as ciprofloxacin susceptible (MIC, ≤1 μg/ml) according to the NCCLS recommendations. A total of 62 isolates were resistant to nalidixic acid (MIC, ≥32 μg/ml). The MIC histogram of ciprofloxacin for all Salmonella isolates showed a bimodal distribution with a range of 0.008 to 0.5 μg/ml (Fig. 1). The isolates were divided into two populations based on nalidixic acid susceptibility, with the ciprofloxacin MICs ranging from 0.008 to 0.064 μg/ml for the nalidixic acid-susceptible population and from 0.032 to 0.5 μg/ml for the nalidixic acid-resistant population.

FIG. 1.

Ciprofloxacin (CIP) MIC histogram for 1,010 epidemiologically unrelated Salmonella isolates collected in Finland from 1995 to 1998. The MICs of ciprofloxacin are plotted on the x axis, and the number of isolates are plotted on the y axis. White columns indicate nalidixic acid-susceptible (n = 948) isolates, and black columns indicate nalidixic acid-resistant (n = 62) isolates.

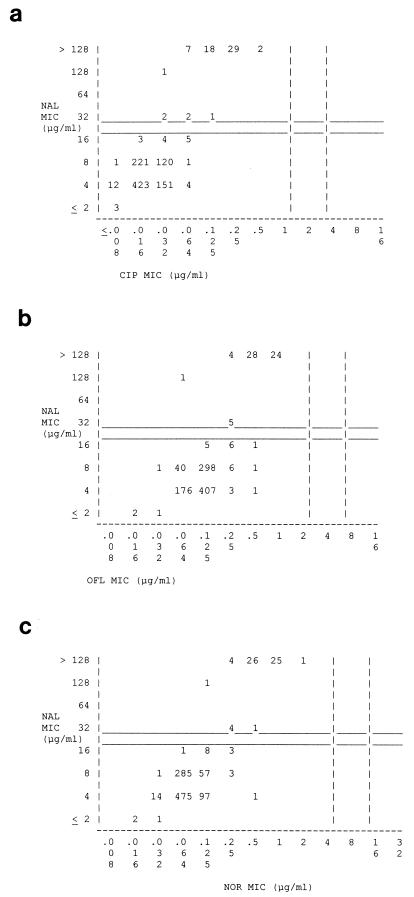

The scattergram correlating the MICs of ciprofloxacin and nalidixic acid for the Salmonella isolates illustrates the simultaneous presence of nalidixic acid resistance and decreased ciprofloxacin susceptibility in our Salmonella population (Fig. 2a). All 31 isolates for which the ciprofloxacin MICs were ≥0.25 μg/ml were highly resistant to nalidixic acid (MIC, >128 μg/ml). Of the 19 isolates for which the ciprofloxacin MIC was 0.125 μg/ml, all except one, for which the MIC was 32 μg/ml, were highly resistant to nalidixic acid. Only three isolates for which the MIC of ciprofloxacin was <0.064 μg/ml were nalidixic acid resistant. The scattergrams presenting the correlations between the MICs of nalidixic acid and ofloxacin (Fig. 2b) and those of nalidixic acid and norfloxacin (Fig. 2c) revealed similar associations.

FIG. 2.

Scattergrams for 1,010 Salmonella isolates correlating the MICs of nalidixic acid to those of ciprofloxacin (a), ofloxacin (b), and norfloxacin (c). The vertical dashed lines of panels a to c indicate the NCCLS breakpoint recommendations for susceptibility and resistance, respectively, to ciprofloxacin (MIC, ≤1 and ≥4 μg/ml), ofloxacin (MIC, ≤2 and ≥8 μg/ml), and norfloxacin (MIC, ≤4 and ≥16 μg/ml). The horizontal solid lines indicate the respective NCCLS breakpoint recommendations for nalidixic acid (MIC, ≤16 and ≥32 μg/ml). The numbers within the graph indicate the numbers of Salmonella isolates. CIP, ciprofloxacin; OFL, ofloxacin; NOR, norfloxacin; NAL, nalidixic acid.

Disk diffusion test results.

All 129 Salmonella (the 62 nalidixic acid-resistant and 67 randomly selected nalidixic acid-susceptible) isolates evaluated by means of disk diffusion tests were classified as ciprofloxacin susceptible according to the NCCLS recommendations (inhibition zone diameter, ≥21 mm). The mean inhibition zone diameters around nalidixic acid and five fluoroquinolone disks (three different fluoroquinolones) for these isolates are shown in Table 1. The differences in the inhibition zone diameters between the two study groups were statistically significant regarding every fluoroquinolone tested, supporting the association between nalidixic acid resistance and decreased fluoroquinolone susceptibility.

TABLE 1.

Mean zone diameters around nalidixic acid and five fluoroquinolone disks for 62 nalidixic acid-resistant and 67 nalidixic acid-susceptible Salmonella isolates

| Agent (disk content) | Nalidixic acid-resistant isolates (MIC, ≥32 μg/ml)

|

Nalidixic acid-susceptible isolates (MIC, ≤16 μg/ml)

|

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD (mm) | Range (mm) | Mean ± SD (mm) | Range (mm) | ||

| Nalidixic acid (30 μg)a | 6.6b | 6–14 | 22.7 ± 2.4 | 15–29 | <0.001 |

| Ciprofloxacin (5 μg)a | 30.8 ± 2.6 | 26–40 | 38.4 ± 2.3 | 33–44 | <0.001 |

| Ciprofloxacin (10 μg) | 33.3 ± 2.3 | 28–40 | 40.6 ± 2.4 | 35–46 | <0.001 |

| Ofloxacin (5 μg)a | 24.4 ± 2.7 | 20–34 | 32.1 ± 2.0 | 28–38 | <0.001 |

| Norfloxacin (5 μg) | 26.1 ± 2.4 | 19–34 | 34.4 ± 1.9 | 29–39 | <0.001 |

| Norfloxacin (10 μg)a | 28.9 ± 2.4 | 23–37 | 36.3 ± 2.5 | 30–45 | <0.001 |

Disk content as recommended by the NCCLS.

Standard deviation cannot be calculated.

Ciprofloxacin MICs versus disk diffusion tests.

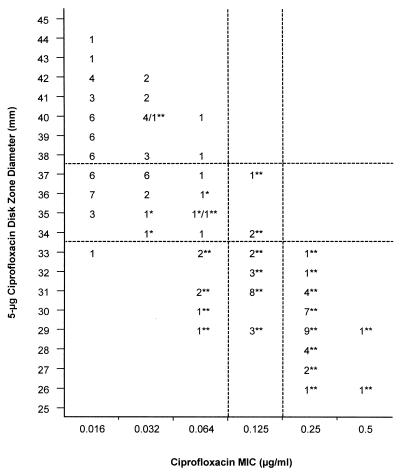

The correlations between the ciprofloxacin MICs and zone diameters around 5-μg ciprofloxacin disks for the 129 Salmonella isolates described above are shown in Fig. 3. All 31 isolates for which the ciprofloxacin MICs were ≥0.25 μg/ml had inhibition zone diameters of ≤33 mm. The inhibition zone diameter also was ≤33 mm for 16 isolates for which the MIC of ciprofloxacin was 0.125 μg/ml and 7 isolates for which the MICs of ciprofloxacin were between 0.064 and 0.016 μg/ml. All 50 isolates for which the ciprofloxacin MICs were ≥0.125 μg/ml had inhibition zone diameters of ≤37 mm. Also 38 isolates for which the MICs of ciprofloxacin were between 0.064 and 0.016 μg/ml were included in this category.

FIG. 3.

Scattergram plotting the MICs of ciprofloxacin (x axis) and the inhibition zone diameters around a 5-μg ciprofloxacin disk (y axis) for 62 nalidixic acid-resistant and 67 nalidixic acid-susceptible Salmonella isolates. Nalidixic acid-resistant isolates (MIC, ≥32 μg/ml) are indicated with an asterisk, and the resistant isolates exhibiting a mutation in the gyrA gene are indicated with a double asterisk. The dashed lines are discussed in the text.

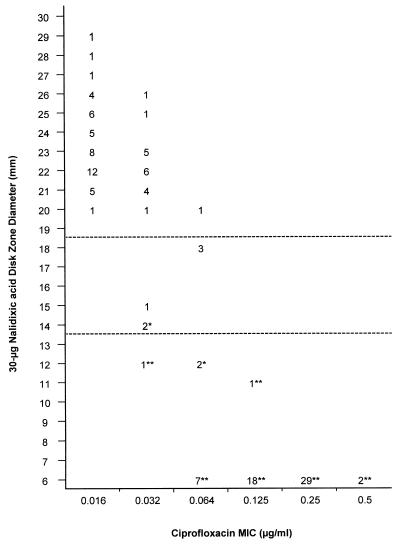

The correlations between the ciprofloxacin MICs and zone diameters around 30-μg nalidixic acid disks for these same isolates are shown in Fig. 4. Of the 60 isolates classified as nalidixic acid resistant according to the NCCLS recommendations (inhibition zone diameter, ≤13 mm), there were 31 for which the ciprofloxacin MICs were ≥0.25 μg/ml, 19 for which the MIC was 0.125 μg/ml, and 10 for which the MICs were between 0.064 and 0.032 μg/ml. All isolates for which the ciprofloxacin MICs were ≥0.25 μg/ml showed no zones to nalidixic acid disks (6 mm).

FIG. 4.

Scattergram plotting the MICs of ciprofloxacin (x axis) and the inhibition zone diameters around a 30-μg nalidixic acid disk (y axis) for 62 nalidixic acid-resistant and 67 nalidixic acid-susceptible Salmonella isolates. The horizontal dashed lines indicate the NCCLS recommendations for susceptibility (inhibition zone diameter, ≥19 mm) and resistance (inhibition zone diameter, ≤13 mm) to nalidixic acid. Isolates designated as resistant to nalidixic acid based on MIC (≥32 μg/ml) determinations are indicated with an asterisk, and the resistant isolates exhibiting a mutation in the gyrA gene are indicated with a double asterisk.

Screening for isolates with decreased ciprofloxacin susceptibility.

The relevance of using the resistance to nalidixic acid as a marker for decreased ciprofloxacin susceptibility in salmonellas was evaluated by comparing the MICs of ciprofloxacin and nalidixic acid for the 1,010 Salmonella isolates included (Fig. 2a). When an MIC of ciprofloxacin of ≥0.125 μg/ml was adopted as a breakpoint, screening for nalidixic acid resistance (MIC, ≥32 μg/ml) led to the detection of all 50 isolates with decreased ciprofloxacin susceptibility (MIC, ≥0.125 μg/ml) and, in addition, of 12 of the 960 susceptible isolates. Thus, the sensitivity of the approach was 100%, and the specificity was 98.8%. When an MIC of ciprofloxacin of ≥0.25 μg/ml was selected as a breakpoint, screening for nalidixic acid resistance led to the detection of all 31 isolates with decreased ciprofloxacin susceptibility (MIC, ≥0.25 μg/ml) and, in addition, of 31 of the 979 susceptible isolates, resulting in a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 96.8% of the approach.

Based on the MICs of ciprofloxacin and zone diameters around 30-μg nalidixic acid disks for the 129 Salmonella isolates tested (Fig. 4), screening for nalidixic acid resistance (inhibition zone diameter, ≤13 mm) led to the detection of all isolates for which the MICs were ≥0.125 μg/ml. When this MIC was used as a breakpoint of decreased ciprofloxacin susceptibility, the sensitivity of the nalidixic acid disk screening was 100% and the specificity was 87.3%. Correspondingly, the sensitivity was 100% and the specificity was 70.4% when an MIC of ≥0.25 μg/ml was used as a breakpoint of decreased ciprofloxacin susceptibility.

Finally, the applicability of the 5-μg ciprofloxacin disk diffusion test in detecting decreased ciprofloxacin susceptibility was assessed (Fig. 3). The MICs for 50 of the 88 isolates with an inhibition zone diameter of ≤37 mm were ≥0.125 μg/ml, whereas for all of the isolates with a zone diameter of >37 mm the MICs were ≤0.064 μg/ml. Thus, when an MIC of ≥0.125 μg/ml was adopted as a breakpoint, the ciprofloxacin inhibition zone diameter of ≤37 mm yielded a 100% sensitivity and a 51.9% specificity in screening for decreased ciprofloxacin susceptibility.

Nucleotide sequence analysis.

The QRDR of the gyrA gene was sequenced from all 62 nalidixic acid-resistant isolates (50 for which the ciprofloxacin MICs were ≥0.125 μg/ml) and 23 nalidixic acid-susceptible isolates. All isolates for which the ciprofloxacin MICs were ≥0.125 μg/ml had a mutation in the QRDR of gyrA. Mutated isolates related to ciprofloxacin MICs and 5-μg ciprofloxacin disk zone diameters are shown in Fig. 3, and those related to ciprofloxacin MICs and 30-μg nalidixic acid disk zone diameters are shown in Fig. 4. Altogether, 58 (94%) nalidixic acid-resistant isolates had a mutation in the QRDR of gyrA, whereas none of the nalidixic acid-susceptible isolates analyzed had a mutation in that region. All of the mutations detected were localized at codon 83 or 87. Five different kinds of point mutations were found: two at codon 83 and three at codon 87 (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Mutation in the QRDR of the gyrA gene and the quinolone susceptibility range for 62 nalidixic acid-resistant (NAL-R) and 23 nalidixic acid-susceptible (NAL-S) Salmonella isolatesa

| Isolate and mutation or wild type | Codon change | No. of isolates | MIC range (μg/ml)

|

Disk zone diam range (mm)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAL | CIP | NAL (30 μg) | CIP (5 μg) | |||

| NAL-R (n = 62) | ||||||

| Wild type | No change | 4 | 32 | 0.032–0.064 | 12–14 | 34–36 |

| Ser83→Phe | TCC→TTC | 14 | >128 | 0.25 | 6 | 26–32 |

| Ser83→Tyr | TCC→TAC | 1 | >128 | 0.25 | 6 | 29 |

| Asp87→Asn | GAC→AAC | 20 | >128 | 0.064–0.25 | 6 | 28–37 |

| Asp87→Gly | GAC→GGC | 7 | 128–>128b | 0.032–0.125 | 6–12b | 30–40 |

| Asp87→Tyr | GAC→TAC | 16 | 32–>128c | 0.064–0.5 | 6–11c | 26–34 |

| NAL-S (n = 23), wild type | No change | 23 | 4–16 | 0.016–0.064 | 15–29 | 36–44 |

CIP, ciprofloxacin.

One isolate for which the MIC was 128 μg/ml had a disk zone diameter of 12 mm; others for which the MICs were >128 μg/ml had disk zone diameters of 6 mm.

One isolate for which the MIC was 32 μg/ml had a disk zone diameter of 11 mm; others for which the MICs were >128 μg/ml had disk zone diameters of 6 mm.

DISCUSSION

We have shown in this study that a collection of 1,010 Salmonella isolates classified as fluoroquinolone susceptible according to the NCCLS guidelines contained two distinct subpopulations, with the great majority of the isolates being entirely ciprofloxacin susceptible and a minority exhibiting reduced ciprofloxacin susceptibility (MICs ranging between 0.125 and 0.5 μg/ml). Although at the present time the MICs of ≤1 and ≥4 μg/ml are still widely accepted as breakpoints of ciprofloxacin susceptibility and resistance, respectively, many authors have focused attention on Salmonella isolates with decreased susceptibility (2, 4, 7, 10, 11, 13, 18, 19, 21, 24–27). Indeed, recognition of these strains is of concern due to the increasing number of treatment failures in invasive salmonellosis reported in association with reduced fluoroquinolone susceptibility. We believe that, in addition to the categories of resistant and fully susceptible, a category of decreased fluoroquinolone susceptibility could be useful in the susceptibility determinations of salmonellas. A corresponding classification is accepted for the Neisseria gonorrhoeae species (5, 8, 9, 17).

In most laboratories, the proportion of reported Salmonella strains with decreased fluoroquinolone susceptibility is still small compared to the fully susceptible population. Therefore, alertness is required to recognize these strains. It has been previously recommended, based mainly on solitary cases of fluoroquinolone treatment failures, that all isolates of the Salmonella species should be tested for nalidixic acid resistance in order to avoid reporting false susceptibility to fluoroquinolones (10, 26). In our collection of clinical Salmonella isolates, nalidixic acid susceptibility testing proved both sensitive and specific in screening for isolates with decreased ciprofloxacin susceptibility. Identification of nalidixic acid resistance by the disk diffusion method led to the detection of all isolates for which the MICs of ciprofloxacin were ≥0.125 μg/ml, providing a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 87.3% as a screening approach. Alternatively, nalidixic acid MICs can be employed as a basis for screening. Calculated by the MIC determinations for our Salmonella isolates, the sensitivity of finding isolates for which the MICs of ciprofloxacin were ≥0.125 μg/ml was 100% and the specificity was 98.8%, when an MIC of nalidixic acid of ≥32 μg/ml was used as a selection criterion. Technically, screening could be accomplished by using a selective breakpoint plate containing nalidixic acid in a concentration of 16 μg/ml, which allows the growth of Salmonella isolates for which the MICs of nalidixic acid are ≥32 μg/ml.

According to the NCCLS recommendations, all Salmonella isolates should be routinely tested for susceptibility to ampicillin, a quinolone, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and the extraintestinal isolates should be tested, in addition, for susceptibility to chloramphenicol and an expanded-spectrum cephalosporin (17). In this context, most laboratories evidently use one of the fluoroquinolones, since nalidixic acid is not administered for the treatment of Salmonella infections. Therefore, an approach of including an additional nalidixic acid disk in all susceptibility testing may not be cost-effective in field laboratories. The results of the present study also suggest that the ciprofloxacin disk diffusion test can be applied to detect decreased ciprofloxacin susceptibility: a zone diameter of ≤37 mm around a 5-μg ciprofloxacin disk was appropriate as a selection criterion to find all Salmonella isolates for which the MICs were ≥0.125 μg/ml. Admittedly, a considerable number of isolates for which the MICs of ciprofloxacin were ≥0.064 μg/ml were also included in this category. Thus, a further screening with a 30-μg nalidixic acid disk (inhibition zone diameter, ≤13 mm) could be used to decrease the number of isolates referred to full-range ciprofloxacin MIC determinations.

In addition to a mutation in the QRDR of the gyrA gene, decreased permeability and active efflux have been reported to confer low-level resistance to fluoroquinolones (12, 20). In the present study, a mutation of the gyrA gene could be demonstrated in all isolates with decreased ciprofloxacin susceptibility and in 94% of the nalidixic acid-resistant isolates. All of the five different mutations detected have been previously described in the literature in association with fluoroquinolone resistance in salmonellas (2, 6, 18, 22, 23). No mutations in the QRDR of the gyrA gene were observed in four (6%) of our nalidixic acid-resistant isolates, indicating other mechanisms of resistance. At the present time, it is important to keep in mind that a mutation may not always translate into clinical resistance. Moreover, the fluoroquinolone treatment failures reported in salmonellosis have, so far, been anecdotal. The final proof of the clinical importance of these less fluoroquinolone susceptible Salmonella strains can be obtained only after careful, randomized, controlled studies. Such studies are urgently needed.

In our Salmonella population, all isolates manifesting decreased fluoroquinolone susceptibility were nalidixic acid resistant. Consistently, previous studies have shown that all Salmonella strains recovered from patients who failed fluoroquinolone therapy have been resistant to nalidixic acid, suggesting an alteration in DNA gyrase as a consequence of mutation (2, 10, 11, 18, 19, 21, 26, 27). This finding is interesting and could explain the emergence of clinical fluoroquinolone resistance in this particular group of isolates, since it is conceivable that the bacterial strains which have undergone one mutation are easily prone to a second mutation, resulting in high-level fluoroquinolone resistance (3). Unexpectedly, Salmonella strains isolated from patients after unsuccessful fluoroquinolone treatment have commonly expressed only low-level resistance to this antimicrobial group. However, there are data showing that the presence of nalidixic acid resistance, in and of itself, may occasionally influence the therapeutic outcome of salmonellosis. According to a recent report from Vietnam, treatment failures with short-course ofloxacin for uncomplicated typhoid were significantly more common in patients infected with nalidixic acid-resistant strains than in those infected with susceptible strains (27).

In recent years, many papers have focused on fluoroquinolone resistance in Salmonella isolates with special reference to strains for which the ciprofloxacin MICs were ≥0.125 μg/ml (2, 10, 11, 21, 24, 26, 27). In England and Wales, ciprofloxacin resistance (MIC, ≥0.25 μg/ml) in salmonellas increased from 0.3 to 2.1% between 1991 and 1994 (4). In that country, low-level resistance (MIC, 0.125 to 1 μg/ml) was identified in 1996 in 7% of Salmonella serovar Typhi, 4% of Salmonella serovar Paratyphi A, and 4% of nontyphoidal salmonellas (25). We have shown that in Finland ciprofloxacin resistance (MIC, ≥0.25 μg/ml) emerged during the years 1995 to 1997 among the domestic Salmonella isolates, with the proportion of resistant strains increasing from 0.0 to 2.2% (7). Among the foreign salmonellas isolated in our country, the simultaneous increase (from 2.0 to 8.4%) was statistically significant (P = 0.037). It is of note that similar strains would have been classified as susceptible in those microbiological laboratories which follow the current breakpoint recommendations. Thus, the lack of universally observed guidelines for breakpoints of susceptibility and resistance severely impedes the worldwide surveillance of the emergence and spread of fluoroquinolone-resistant Salmonella strains, as well as of those with decreased fluoroquinolone susceptibility.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated here the presence of a defined subpopulation with decreased fluoroquinolone susceptibility in our Salmonella collection. These isolates differed from the fully fluoroquinolone-susceptible population by being uniformly resistant to nalidixic acid and exhibiting a mutation in the QRDR of the gyrA gene. We regard it as important that microbiology laboratories endeavor to recognize these less susceptible Salmonella strains, in order to reveal their clinical importance and to survey their epidemic spread. In our large collection of clinical Salmonella isolates, detection of nalidixic acid resistance by the disk diffusion method proved useful as a tool to screen for decreased ciprofloxacin susceptibility.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Maud Kuistila Memorial Foundation (to A.H.) and the Scandinavian Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (to P.H.) have supported this work.

We thank Katrina Lager, Minna Lamppu, Erkki Nieminen, and Tuula Randell for technical help.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asperilla M O, Smego R A, Jr, Scott L K. Quinolone antibiotics in the treatment of Salmonella infections. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12:873–889. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.5.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown J C, Thomson C J, Amyes S G. Mutations of the gyrA gene of clinical isolates of Salmonella typhimurium and three other Salmonella species leading to decreased susceptibilities to 4-quinolone drugs. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37:351–356. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drlica K, Zhao X. DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:377–392. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.3.377-392.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frost J A, Kelleher A, Rowe B. Increasing ciprofloxacin resistance in salmonellas in England and Wales 1991–1994. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37:85–91. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuchs P C, Barry A L, Baker C, Murray P R, Washington J A., II Proposed interpretive criteria and quality control parameters for testing in vitro susceptibility of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to ciprofloxacin. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2111–2114. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.10.2111-2114.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griggs D J, Gensberg K, Piddock L J. Mutations in gyrA gene of quinolone-resistant Salmonella serotypes isolated from humans and animals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1009–1013. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.4.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hakanen A, Siitonen A, Kotilainen P, Huovinen P. Increasing fluoroquinolone resistance in salmonella serotypes in Finland during 1995–1997. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;43:145–148. doi: 10.1093/jac/43.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kam K M, Wong P W, Cheung M M, Ho N K. Detection of quinolone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1462–1464. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.6.1462-1464.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knapp J S, Hale J A, Neal S W, Wintersheid K, Rice R J, Whittington W L. Proposed criteria for interpretation of susceptibilities of strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, enoxacin, lomefloxacin, and norfloxacin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2442–2445. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.11.2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Launay O, Van J-C N, Buu-Hoi A, Acar J F. Typhoid fever due to a Salmonella typhi strain of reduced susceptibility to fluoroquinolones. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1997;3:541–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1997.tb00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le Lostec Z, Fegueux S, Jouve P, Cheron M, Mornet P, Boisivon A. Reduced susceptibility to quinolones in Salmonella typhi acquired in Europe: a clinical failure of treatment. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1997;3:576–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1997.tb00313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martinez J L, Alonso A, Gomez-Gomez J M, Baquero F. Quinolone resistance by mutations in chromosomal gyrase genes. Just the tip of the iceberg? J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;42:683–688. doi: 10.1093/jac/42.6.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCarron B, Love W C. Acalculous nontyphoidal salmonellal cholecystitis requiring surgical intervention despite ciprofloxacin therapy: report of three cases. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:707–709. doi: 10.1093/clind/24.4.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murdoch D A, Banatvala N A, Bone A, Shoismatulloev B I, Ward L R, Threlfall E J. Epidemic ciprofloxacin-resistant Salmonella typhi in Tajikistan. Lancet. 1998;351:339. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)78338-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 4th ed. Approved standard M7-A4. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests, 6th ed. Approved standard M2-A6. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Ninth informational supplement M100-S9. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ouabdesselam S, Tankovic J, Soussy C J. Quinolone resistance mutations in the gyrA gene of clinical isolates of Salmonella. Microb Drug Resist. 1996;2:299–302. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1996.2.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pers C, Sogaard P, Pallesen L. Selection of multiple resistance in Salmonella enteritidis during treatment with ciprofloxacin. Scand J Infect Dis. 1996;28:529–531. doi: 10.3109/00365549609037954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piddock L J. Mechanisms of resistance to fluoroquinolones: state-of-the-art 1992–1994. Drugs. 1995;49:29–35. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199500492-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piddock L J, Griggs D J, Hall M C, Jin Y F. Ciprofloxacin resistance in clinical isolates of Salmonella typhimurium obtained from two patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:662–666. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.4.662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piddock L J, Ricci V, McLaren I, Griggs D J. Role of mutation in the gyrA and parC genes of nalidixic-acid-resistant salmonella serotypes isolated from animals in the United Kingdom. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;41:635–641. doi: 10.1093/jac/41.6.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reyna F, Huesca M, Gonzalez V, Fuchs L Y. Salmonella typhimurium gyrA mutations associated with fluoroquinolone resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1621–1623. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.7.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rowe B, Ward L R, Threlfall E J. Ciprofloxacin-resistant Salmonella typhi in the UK. Lancet. 1995;346:1302. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91906-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Threlfall E J, Graham A, Cheasty T, Ward L R, Rowe B. Resistance to ciprofloxacin in pathogenic Enterobacteriaceae in England and Wales in 1996. J Clin Pathol. 1997;50:1027–1028. doi: 10.1136/jcp.50.12.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vasallo F J, Martin-Rabadan P, Alcala L, Garcia-Lechuz J M, Rodriguez-Creixems M, Bouza E. Failure of ciprofloxacin therapy for invasive nontyphoidal salmonellosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:535–536. doi: 10.1086/517087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wain J, Hoa N T, Chinh N T, Vinh H, Everett M J, Diep T S, Day N P, Solomon T, White N J, Piddock L J, Parry C M. Quinolone-resistant Salmonella typhi in Viet Nam: molecular basis of resistance and clinical response to treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:1404–1410. doi: 10.1086/516128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]