Abstract

Absence of Ku80 results in increased sensitivity to ionizing radiation, defective lymphocyte development, early onset of an age-related phenotype, and premature replicative senescence. Here we investigate the role of p53 on the phenotype of ku80-mutant mice and cells. Reducing levels of p53 increased the cancer incidence for ku80−/− mice. About 20% of ku80−/− p53+/− mice developed a broad spectrum of cancer by 40 weeks and all ku80−/− p53−/− mice developed pro-B-cell lymphoma by 16 weeks. Reducing levels of p53 rescued populations of ku80−/− cells from replicative senescence by enabling spontaneous immortalization. The double-mutant cells are impaired for the G1/S checkpoint due to the p53 mutation and are hypersensitive to γ-radiation and reactive oxygen species due to the Ku80 mutation. These data show that replicative senescence is caused by a p53-dependent cell cycle response to damaged DNA in ku80−/− cells and that p53 is essential for preventing very early onset of pro-B-cell lymphoma in ku80−/− mice.

Ku80 (also called Ku86), Ku70, DNA-PKCS, Xrcc4, and DNA ligase IV are critical for the repair of DNA ends by nonhomologous end joining (reviewed in references 26 and 33). Ku80 forms a heterodimer with Ku70, called Ku, that binds to DNA ends, nicks, gaps, and hairpins (11, 28). In vitro, Ku forms a complex called DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK) by associating with a 450-kDa catalytic subunit, DNA-PKCS. Cells mutated by the deletion of any of these genes are hypersensitive to ionizing radiation and defective in repairing DNA double-strand breaks formed during the assembly of the V(D)J segments of antigen receptor genes (2, 14, 15, 17, 32, 35). Mice deficient for DNA-PKCS (severe combined immunodeficiency [scid]) or Ku are immune compromised, lacking mature lymphocytes (3, 10, 18, 30, 31, 40). In addition to decreased radiation resistance and lymphogenesis, mice with deletions of genes for Xrcc4 and DNA ligase IV are embryonically lethal and exhibit neuronal apoptosis (16).

Mice with a deleted Ku80 gene prematurely exhibit some signs of aging that include atrophic skin and hair follicles, osteopenia, premature growth plate closure, hepatocellular degeneration, and shortened life span (39). Additionally, ku80−/− cells exhibit replicative senescence (18, 30), a process that describes the progressively limited proliferation potential of cells grown in tissue culture (23). Replicative senescence is likely a mechanism that reduces cancer incidence and may influence organismic senescence (8).

Here, we investigate the phenotype of ku80−/− mice and cells in a p53-deficient background. We chose to investigate p53 because it is a tumor suppressor protein important for cell cycle checkpoints that respond to DNA damage (reviewed in references 13 and 24) and replicative senescence (5). We find that reducing levels of p53 greatly increased cancer incidence in ku80−/− mice. About 20% of p53+/− ku80−/− mice die from a broad spectrum of cancer, typical of p53+/− mice, and that nearly 100% of p53−/− ku80−/− mice die from pro-B-cell lymphoma. In addition, we find that replicative potential is restored to ku80-mutant cells simply by reducing levels of p53. Typical of p53-mutant cells, the double-mutant cells exhibited a great proliferation potential, were readily immortalized, and were defective for the G1/S checkpoint in response to ionizing radiation. Typical of ku80-mutant cells, the double-mutant cells were hypersensitive to DNA damaging agents. These data suggest that the p53-dependent G1/S checkpoint, in response to spontaneously damaged DNA, is responsible for replicative senescence in ku80−/− cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genotyping by the PCR.

The p53 genotype was determined by PCR as described by Timme and Thompson (36) with the following modifications: sense primer 5N (5′GTGGGAGGGACAAAAGTTCGAGGCC3′) detects both wild-type and mutant alleles, antisense primer 3W2 (5′ATGGGAGGCTGCCAGTCCTAACCC3′) detects only wild-type alleles, and antisense primer 3N2 (5′TTTACGGAGCCCTGGCGCTCGATGT3′) detects only mutant alleles. Wild-type (0.55 kb) and mutant (0.15 kb) fragments were separated by electrophoresis on a 1.2% ethidium bromide-stained gel. PCR mixtures were preincubated at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of amplification at 94°C for 30 s, 59°C for 1 min (with a 1-min ramp), and 72°C for 30 s in a Perkin-Elmer DNA Thermal Cycler 480. Both PCR products were sequenced to prove they were not artifacts, and results were confirmed by described Southern analysis protocols (12). Ku80 genotypic analysis by PCR was performed as previously described (39).

Tumor analysis.

Cell suspensions were prepared, preincubated with Fc-block (Pharmingen) to reduce binding to FcγII and FcγIII receptors, and stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies to cell surface markers as previously described for flow cytometry (4). Monoclonal antibodies (Pharmingen) to the following markers were used to determine tumor type: CD3-R-phycoerythrin (PE), CD4-cychrome (CY), CD8-fluoroscein isothiocyanate (FITC), CD43-PE, CD45R-CY (B220), and immunoglobulin M (IgM)-FITC. For DNA content analysis, cells were first stained with monoclonal antibodies to the indicated surface markers according to previously published procedures (6) except that phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was used instead of sodium citrate buffer. Samples were analyzed on a Coulter Epics XL flow cytometer. One early-passage cell line derived from a p53−/− ku80−/− tumor was subjected to karyotype analysis as previously described (19, 29, 37).

Fibroblast analysis.

Murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) were generated from E14.5 day embryos by standard procedures. Murine skin fibroblasts (MSF) were generated from ears after being cut into small 1-mm2 pieces and plated onto a 6-cm-diameter plate (passage zero) and harvested 14 to 15 days later. 3T3 equivalent analysis was performed with MEF (2 × 105 cells/3.5-cm plate) plated onto three different plates. Every 4 days, cells were trypsinized, combined, counted, and plated at their original concentration onto another three plates. As cell number declined, cells were plated onto fewer plates, but always at the same concentration. Passaging was discontinued when less than the number of cells needed for one plate remained. Colony size distribution (CSD) was performed with fibroblasts (passage 1 or 2) plated onto three 10-cm plates at various concentrations (500, 1,000, or 5,000 cells/10-cm plate) and stained with crystal violet 2 weeks later. Colonies of four or greater cells were counted. The fraction of those colonies with 16 or more cells was determined.

Checkpoint analysis.

Passage 1 MEF were synchronized by allowing them to grow to confluence and remain confluent for 4 to 6 days. Additionally, the cells were serum starved (0.1% fetal bovine serum) for 50 h. For analysis of the G1/S checkpoint, cells were trypsinized, irradiated with either 0 or 500 rad (137Cs, Gammator B, 290 rad/min) and replated at a high, but subconfluent, concentration (1 × 106 cells/10-cm plate) in 10% fetal bovine serum and 10 μM bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU). Cells were collected and fixed in 70% ethanol 19 h later. For the G2/M checkpoint, cells were trypsinized and replated at a high, but subconfluent, concentration (1 × 106 cells/10-cm plate) in 10% fetal bovine serum. BrdU (10 μM) was added 18 h later. After 2 h in BrdU, cells were washed, exposed to either 0 or 500 rad, and then incubated for another 8 h without BrdU. Cells were then harvested and fixed in 70% ethanol.

Fixed cells were incubated in 0.1 M HCl and 0.5% Triton X-100 for 10 min on ice and washed with PBS and placed in a boiling water bath for 10 min. After washing with PBS, cells were incubated with 5 μg of anti-BrdU-FITC antibody (Boehringer Mannheim) per ml containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were counterstained with 5 μg of propidium iodide/ml containing 200 μg of RNase/ml. MEF were counted by bivariate fluorescence-activated cell-sorting (FACS) analysis with a Becton Dickinson FACScan. The BrdU-labeled cells were quantitated.

Genotoxic analysis. (i) Low-density plating.

Dose response to γ-radiation or H2O2 was determined as follows. Exponentially growing MEF (passages 2 to 3) were trypsinized and irradiated with a 137Cs irradiator (Gammator B, 290 rad/min) or exposed to a single continuous dose of H2O2 (0.5 × 10−4, 1 × 10−4, [1.5 × 10−4]% H2O2 added the day of plating and the medium was not changed). MEF exposed to either γ-radiation or H2O2 were plated at various concentrations onto three 10-cm plates (500, 1,000, 5,000 or 10,000 cells/10-cm plate), and colonies were stained with crystal violet 2 weeks later. Colonies of four or more cells were counted for ku80−/− MEF and colonies of 16 or more cells were counted for all other genotypes. MEF without exposure to γ-radiation or H2O2 served as a control. The survival fraction of cells exposed to either γ-radiation or H2O2 was calculated from the low-density plating.

(ii) High density plating.

Dose response to H2O2 or streptonigrin (Sigma) was determined as follows. MEF (passage 2) were trypsinized and continuously grown in a single dose of H2O2 (2 × 10−4, 4 × 10−4, or [6 × 10−4]% added the day of plating and the medium was not changed) or streptonigrin (1 × 10−5, 2 × 10−5, or 10 × 10−5 mg/ml added the day of plating and the medium was not changed) and stained with crystal violet 2 weeks later. MEF exposed to either H2O2 or streptonigrin were plated at various concentrations onto 3.5-cm plates (2 × 105, 2 × 104, or 2 × 103 cells per plate). MEF without exposure to genotoxic agent were plated at various concentrations and served as a control (2 × 105, 2 × 104, 2 × 103, 2 × 102, 2 × 101, and 2 cells per 3.5-cm plate). The survival fraction of cells exposed to streptonigrin was calculated from the high-density plating. With no exposure to streptonigrin, colonies were counted for cells that grew when plated at 2 × 102 cells/3.5-cm plate. With exposure to streptonigrin, colonies were counted for cells that grew when plated at 2 × 104 cells/3.5-cm plate.

RESULTS

Deficiency of p53 shortens life span for ku80−/− mice.

As previously reported, the life spans of ku80−/− (39), p53+/−, and p53−/− mice (12, 21) are shorter than those of wild-type mice. Comparing the data shows that life span progressively increases in the following order: p53−/− < ku80−/− < p53+/− < wild type. However, the causative factors that shortened life span are very different. For ku80−/− mice, the causative factor is age-specific mortality brought on by an early onset of senescence. For p53+/− and p53−/− mice, the causative factor is increased cancer incidence.

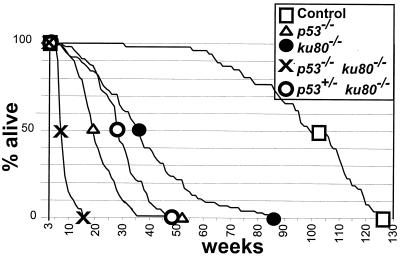

The survival curves of ku80−/− mice in a p53+/− and a p53−/− background are compared to those of ku80−/−, p53+/−, p53−/−, and control mice (p53+/+ mice in either a ku80+/+ or ku80+/− background) (Fig. 1; Table 1). Mutation of one p53 gene significantly shortened the life span for ku80−/− mice (P > 0.005). Onset of age-specific mortality was about 10 weeks, 50% mortality was about 28 weeks, the average life span was 29 ± 7 weeks, and the longest-lived mouse was 49 weeks for a cohort of 85 p53+/− ku80−/− mice. Life span was much shorter for ku80−/− mice in a p53−/− background. Onset of age-specific mortality was about 6 weeks, 50% mortality was about 7 weeks, the average life span was 8.6 ± 1.8 weeks, and the longest-lived mouse was 16 weeks for a cohort of 41 p53−/− ku80−/− mice. Thus, the life span of ku80−/− mice depends on levels of p53.

FIG. 1.

Life span and mortality. The survival curve begins after weaning (3 weeks) because deletion of Ku80 genes reduced fitness that often resulted in neonatal death (30). Symbols are shown at the points of 100, 50, and 0% survival. Observed were 47 control mice, 124 p53−/− mice, 89 ku80−/− mice, 41 p53−/− ku80−/− mice, and 85 p53+/− ku80−/− mice.

TABLE 1.

Summary of life span and cancer data

| Cohort | Life span (weeks)

|

Cancer incidence (%)a

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality onset | 50% survival | Total incidence | Lymphoma | Osteosarcoma | Rhabdomyosarcoma | Hemangiosarcoma | Undifferentiated sarcoma | Leiomyosarcoma sarcoma | Myxosarcoma sarcoma | Carcinoma | Otherb | |

| Controlc | 56 | 102 | 28 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 4 |

| ku80−/−c | 8 | 36 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| p53−/−d | 7 | 19 | >90e | 59 | 3 | 0 | 18 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 13 |

| p53+/−d | 40 | 77 | >80e | 32 | 32 | 5 | 10 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 12 | 5 |

| p53−/−ku80−/− | 6 | 7 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2f |

| p53+/−ku80−/− | 10 | 28 | 20 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

Sum of the categories for cancer incidence may be greater than total incidence due to multiple-tumor burden in individual mice.

Data are from reference 39.

Data for p53+/− and p53−/− cancer incidence and p53+/− life span are from reference 21.

Data are from personal communication from Lawrence A. Donehower.

One case of testicular teratoma accounts for this 2%.

Deficiency of p53 increases cancer incidence for ku80−/− mice.

Cancer incidence and spectrum were observed in ku80−/− mice in a p53+/− background because mutation of one p53 gene increases cancer incidence, likely due to haploinsufficiency (21, 38). An intermediate cancer incidence was observed for p53+/− ku80−/− mice (20%) compared to that of p53+/− mice (greater than 98%) and ku80−/− mice (2%) (Table 1). Seventeen of 85 p53+/− ku80−/− mice were observed to have cancer (Table 1). p53+/− ku80−/− mice exhibited a broad spectrum of tumors that is similar to that of p53+/− mice (21, 38) (Table 1). Thus, reduction of p53 increased cancer incidence and spectrum for ku80−/− mice.

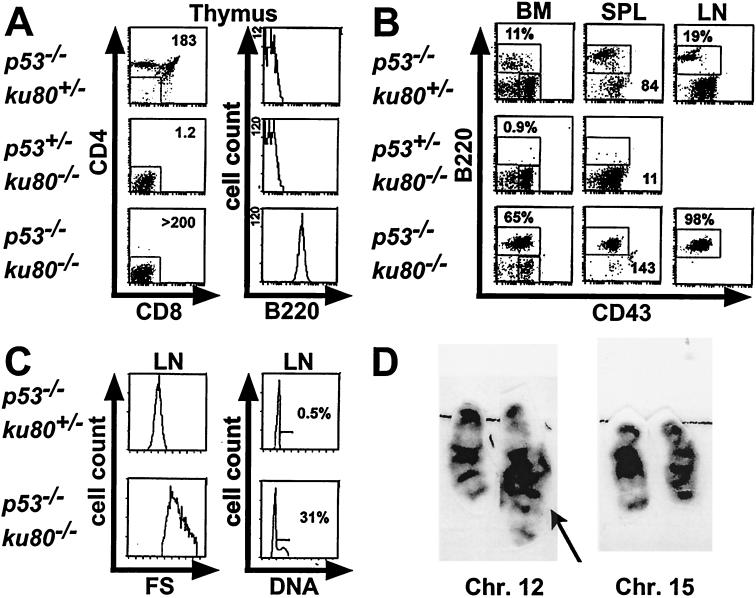

Cancer incidence and spectrum were observed in ku80−/− mice in a p53−/− background because scid mice with deleted p53 genes develop B- and T-cell tumors early in life (19, 29). Similar to p53 scid double-mutant mice, p53 ku80 double-mutant mice were heavily burdened with tumors that caused them to die much earlier than either p53−/− or ku80−/− mice (Fig. 1; Table 1). Tumors commonly involved the thymus-perithymic region, spleen, lymph nodes, and bone marrow. Flow cytometric analysis from moribund p53−/− ku80−/− mice revealed that tumors were of B-cell origin (14 of 14 tumors). These tumor cells are CD4− CD8− B220+ CD43med (and negative for CD3 and IgM surface staining; not shown), consistent with an immature stage in B-cell development that most resembles pro-B cells. The size and composition of the lymphoid organs reflected the extreme tumor burden in these animals. For example, the thymus from double-mutant mice was heavily populated with B220+ tumor cells, increasing the overall cellularity almost 200-fold over that of p53+/− ku80−/− mice (Fig. 2A). Likewise, the spleen weight was almost double that of a normal mouse and was 13-fold that of a p53+/− ku80−/− mouse (Fig. 2B). The lymph node tumor cells were heterogeneously large and cycling, as shown in the forward scatter and DNA content profiles (Fig. 2C). In addition to malignant lymphoma, one 7-week-old mouse had malignant teratoma of the testis (Table 1).

FIG. 2.

Flow cytometric tumor analysis. Moribund p53−/− ku80−/− mice showing signs of enlarged lymph nodes or thymi were subjected to necropsy, and cell suspensions were stained for CD4, CD8, B220, and CD43. Representative profiles are shown for an 8-week-old p53−/− ku80+/− mouse, a 16-week-old p53+/− ku80−/− mouse, and an 8-week-old p53−/− ku80−/− mouse. Lymphocytes with appropriate forward and side scatter properties were initially gated (not shown) for all profiles. (A) Triple-stained (CD4, CD8, B220) thymocytes are displayed in two histograms. The left panels show CD4 and CD8 profiles. Thymocytes that were negative for CD4 and CD8 were gated (indicated by boxed area) and shown for B220 expression in the second panel. Total thymic cellularity (106) is shown in the upper right corner of the CD4 and CD8 profiles. (B) Histograms of double-stained (B220, CD43) bone marrow (BM), spleen (SPL), and lymph node (LN) cell suspensions are shown. The percentage of B220+ cells is indicated for bone marrow and lymph node cells. For the spleen profiles, the total weight (in milligrams) of intact spleen, prior to preparation of cell suspensions, is shown in the lower right corner. (C) Forward scatter (FS) and DNA content profiles on LN cells that fell into the B220+ gate (boxed area in B220 and CD43 profiles shown in panel B). The mean forward scatter, proportional to cell size, is almost doubled for p53−/− ku80−/− lymph node cells compared to those from p53−/− ku80+/− mice. Over 30% of the lymph node tumor cells are in S/G2 phase. This is in contrast to control lymph node cells which are virtually all resting in G0/G1, an expected result in a genetically normal, antigenically unchallenged animal in a pathogen-free facility. Fluorescence parameters are expressed on a log scale while cell count, forward scatter, and DNA content are on a linear scale. It should be noted that lymph nodes from p53+/− ku80−/− mice were not harvested since they were difficult to find. (D) G-Band karyotype analysis showing chromosomes 12 and 15 from a p53−/− ku80−/− lymphoma. Translocation involving the terminal band of chromosome 12 is indicated by the arrow. This finding was present in 9 out of 9 metaphases examined.

The immunophenotype of younger double-mutant mice (2 to 3 weeks old, six observed), was similar to that of ku80−/− mice since the peripheral lymphoid organs were largely devoid of lymphocytes. The only exception in these pretumorous mice was an elevated number of B220+ CD43med bone marrow cells compared to those of 34 littermates, including 16 p53−/− littermates (data not shown). Together, these results suggest that the lymphomas arising in older p53−/− ku80−/− mice originate in the bone marrow and then rapidly disseminate and that there is a predisposition to B-cell lymphomagenesis in the absence of both p53 and Ku80.

Pro-B cell tumors arising in p53−/− scid mice carry recurrent translocations involving chromosomes 12 and 15, which are dependent on initiation of V(D)J recombination (19, 29, 37). To determine whether the tumors in p53−/− ku80−/− mice might arise through a similar oncogenic mechanism, early-passage cells derived from a tumor were subjected to G-band karyotype analysis (Fig. 2D). All nine metaphases examined showed a translocation between chromosomes 12 and 15, with breakpoints at terminal band F2 in chromosome 12 and at approximate band D position on chromosome 15.

Observation of aging in ku80−/− mice deficient for p53.

p53+/− ku80−/− mice were observed for signs of aging (p53−/− ku80−/− mice die too early for this analysis). By outward appearance, a similar onset of senescence was observed for p53+/− ku80−/− mice as described for ku86−/− mice (39). Histological characteristics of aging were observed for two p53+/− ku86−/− mice at 24 and 38 weeks of age. Both mice exhibited growth plate closure and skin atrophy. Osteopenia was observed for the 38-week-old mouse. These characteristics were not observed for p53+/− ku86−/− mice between 5 and 10 weeks of age (seven observed) or for p53+/− mice at 47 weeks of age (three observed, data not shown).

Proliferation potential of fibroblasts derived from mice as they age.

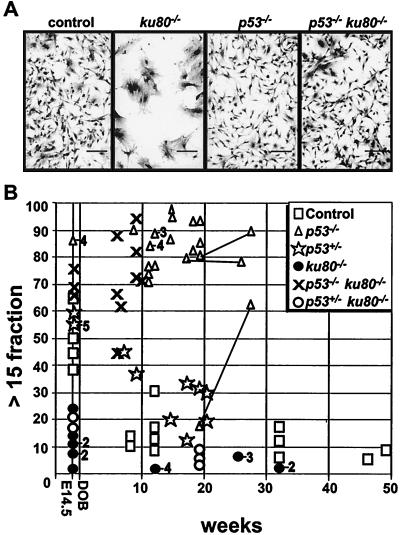

By morphology, ku80−/− MEF entered senescence at early passage (Fig. 3A). These cells appeared postmitotic with increased surface area and spreading and extension of the plasma membrane. However, control, p53−/−, and p53−/− ku80−/− cells were spindle-shaped with less surface area, suggesting a high mitotic index and suggesting that deletion of p53 rescued ku80−/− cells from a postmitotic state.

FIG. 3.

Analysis of individual cells at early passage. (A) MEF morphology. Passage 2 cells were plated (5.3 × 104 cells/3.5-cm plate) and grown for 5 days before staining. Scale bar = 125 μm. (B) Cross-sectional CSD. The fraction of colonies with >15 cells out of the total number of colonies with >3 cells is shown. Symbols are the same as in Fig. 1 with the addition of a star to represent p53+/−. Numbers to the right of a symbol represent the number of clones observed at that point if greater than one. MEF were observed at passage 2 and MSF were observed at passage 1. Skin fibroblasts derived from three p53−/− mice were analyzed at two time points (joined by lines). All other points represent fibroblasts derived from different mice.

Fibroblasts were derived from mice at a variety of ages and analyzed by a cross-sectional CSD to determine the influence age has on cellular proliferation in vivo (Fig. 3B). This assay measures proliferation at the level of an individual cell, at very early passage, by measuring the size of the colony it formed. This assay does not examine the growth potential of an entire population of cells over multiple passages in tissue culture so that genetic alterations are less likely to influence the results. Thus, a cross-sectional CSD is more likely to reflect a cell's in vivo proliferation potential at the time it was derived from the animal, thereby enabling predictions about the influence age has on in vivo cellular proliferation. For this assay, the fraction of colonies with >15 cells was calculated out of the total number of colonies composed of >3 cells. The in vivo proliferation potential would be judged to proportionately increase as the fraction of larger colonies increases. The fraction of larger colonies was found to progressively decline with the age of their human donors (34).

MEF and MSF were observed for their ability to form colonies. For fibroblasts derived from control and p53+/− mice, the fraction of larger colonies progressively decreased with age, suggesting an age-related progressive decline in proliferation potential. By contrast, the fraction of larger colonies was low at all time points for fibroblasts derived from ku80−/− mice and p53+/− ku80−/− mice and high at all time points for fibroblasts derived from p53−/− mice and p53−/− ku80−/− mice. Thus, replicative senescence was initiated during embryonic development for ku80−/− and p53+/− ku80−/− mice but not at all for p53−/− and p53−/− ku80−/− mice. These data show that reducing p53 levels by half had little effect on the colony-forming potential in either control or ku80−/− backgrounds; however, complete deletion of p53 greatly increased the colony-forming potential in both control and ku80−/− backgrounds for cells derived from mice at all ages. Thus, p53 was essential for reducing the larger fraction of colonies for cells derived from control and ku80−/− mice.

p53-dependent, premature replicative senescence observed in ku80-mutant cells.

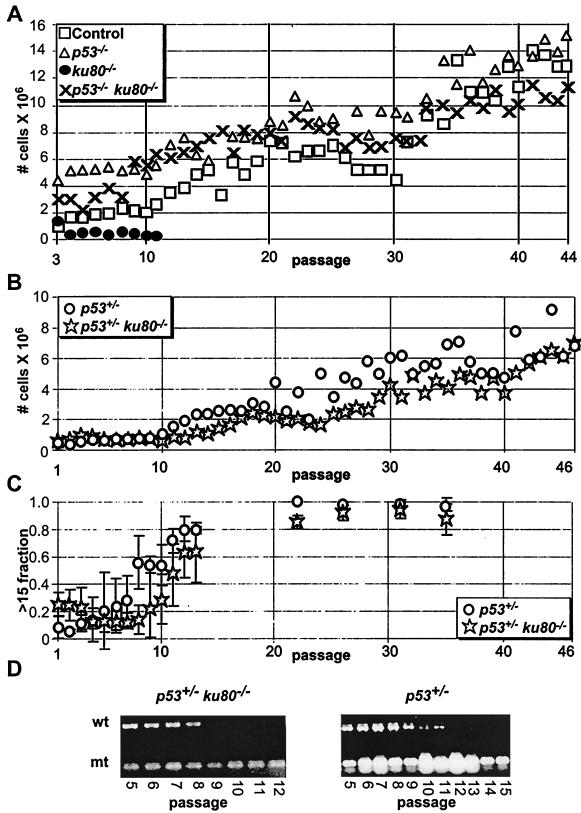

Life span and proliferation potential was observed for clonal populations of cells as they were passaged in tissue culture by a 3T3 equivalent analysis and its companion CSD (Fig. 4). These analyses are different from the cross-sectional CSD in that clonal populations of cells were generated from embryos or mice at comparable ages and analyzed from early to late passage. Thus, the 3T3 equivalent analysis and its companion CSD are less likely to reflect the cell's in vivo proliferation potential as the cross-sectional CSD, but instead allows analysis of the life span for a population of cells and its adaptive potential to spontaneously immortalize.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of clonal populations of cells. Symbols are the same as in Fig. 1 and 3. (A) 3T3 equivalent analysis of control, p53−/−, ku80−/−, and p53−/− ku80−/− MEF. Graph starts with passage 3 MEF. The averages of clones are shown for control (n = 2), p53−/− (n = 3), ku80−/− (n = 2), and p53−/− ku80−/− (n = 2) mice. (B) 3T3 equivalent analysis of p53+/− and p53+/− ku80−/− MSF. Graph starts with passage 1 MSF. The averages of clones are shown for p53+/− (n = 5) and p53+/− ku80−/− (n = 3) MSF. (C) Companion CSD with >15-cell fractions. The fraction of colonies with >15 cells out of the total number of colonies composed of >3 cells is shown. Cells were taken from the 3T3 equivalent analysis presented in panel B. (D) Loss of heterozygosity of p53 shown by genotyping by PCR. Wild-type (wt) and mutant (mt) bands are shown.

The life span of ku80−/− fibroblasts was much shorter than that of control, p53−/−, and p53−/− ku80−/− fibroblasts by a 3T3 equivalent analysis (Fig. 4A). Reduced cell number for ku80−/− MEF was not due to cell death as judged by trypan blue exclusion. In addition, spontaneous immortalization was not observed for any clonal population of ku80−/− MEF (n = 2). By contrast, spontaneous immortalization was observed for all clonal populations of control (n = 2), p53−/− (n = 3), and p53−/− ku80−/− (n = 2) MEF. Thus, replicative senescence of ku80−/− cells is dependent on p53.

Life span and proliferative potential was determined for ku80−/− MSF in a p53+/− background (Fig. 4B to F). MSF were derived from three p53+/− ku80−/− mice and five p53+/− mice between 14 and 20 weeks of age. The life span and proliferation potential of populations of p53+/− ku80−/− MSF clones were tested by a 3T3 equivalent analysis (Fig. 4B). Mutation of one copy of p53 permitted the spontaneous immortalization of the population of ku80−/− cells for all three clones. As cells were passaged during the 3T3 equivalent analysis, the proliferative potential, at the level of an individual cell, was measured by a companion CSD (Fig. 4C). By measuring the fraction of colonies with >15 cells, the proliferative potential progressively increased for p53+/− ku80−/− MSF starting at passage 2 and for p53+/− MSF starting at passage 9. The wild-type and mutant p53 alleles were tested by PCR at each passage to determine loss of heterozygosity (LOH) (22). On average, wild-type p53 was lost by passage 9 ± 2 for p53+/− ku80−/− MSF and by passage 15 ± 2 for p53+/− MSF (Fig. 4D). Thus, increased proliferation potential preceded LOH for both p53+/− and p53+/− ku80−/− cells.

Cellular proliferation, cell cycle checkpoints, and genotoxicity.

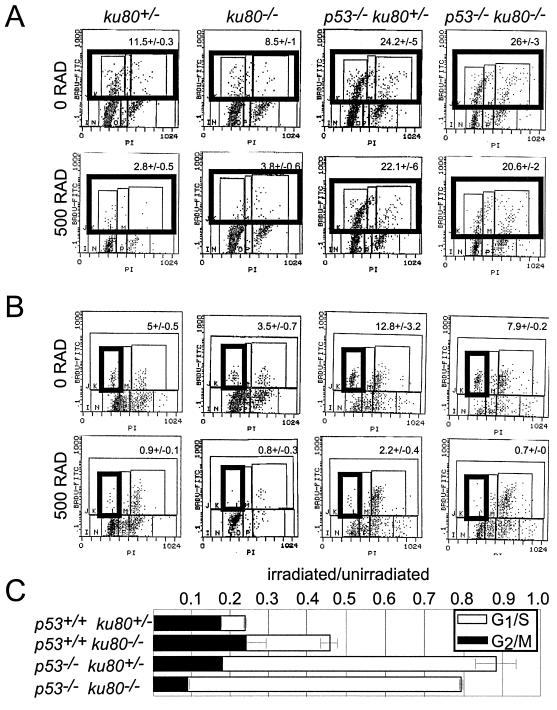

Progression into S phase was analyzed by releasing confluent and serum-starved MEF from quiescence by plating at a high, but subconfluent, concentration in media containing 10% serum (Fig. 5A, top panels). Cells were exposed to BrdU for 19 h after replating. Lower percentages of the population of ku80−/− MEF (8.5 ± 1) and control MEF (11.5 ± 0.3) were labeled with BrdU compared to p53−/− MEF (24.2 ± 5) and p53−/− ku80−/− MEF (26 ± 3). In addition, a higher percentage of cells remained unlabeled in G1 for both ku80−/− MEF (78.5% ± 4%) and control MEF (76.4% ± 1%) compared to p53−/− MEF (53.7% ± 11%) and p53−/− ku80−/− MEF (44.5% ± 4%). These data show that p53 is important for maintaining ku80−/− cells in G1 and decreasing entry into S phase. Thus, replicative senescence in ku80−/− cells could be due to a p53-dependent pathway that inhibits entry into S phase.

FIG. 5.

Cell cycle checkpoints induced by ionizing radiation. (A) Representative histographs for the analysis of the G1/S checkpoint exposed to either 0 or 500 rad. BrdU-labeled cells appear in the top three boxes of each histograph, which are outlined by one box in bold. The average percentage (± standard deviation) of cells labeled with BrdU is shown at the top of each histograph. (B) Representative histographs for the analysis of the G2/M checkpoint exposed to either 0 or 500 rad. BrdU-labeled cells in G1 are shown in the box in bold. The average percentage (± standard deviation) of G1 cells labeled with BrdU is at the top of the histograph. (C) Graph depicting the G1/S (open bar) and G2/M (closed bar) checkpoints. For the G1/S checkpoint, the fraction of irradiated BrdU-labeled cells is divided by the fraction of unirradiated BrdU-labeled cells. For the G2/M checkpoint, the fraction of irradiated BrdU-labeled cells in G1 is divided by the fraction of unirradiated BrdU-labeled cells in G1. The averages of clones are shown for control (n = 2), p53−/− (n = 5), ku80−/− (n = 5), and p53−/− ku80−/− (n = 2) cells.

It is possible that the increased fraction of ku80−/− cells in G1 is due to a p53-dependent cell cycle response to spontaneous DNA damage. This notion is supported by observations that Ku80-deleted cells are intact for checkpoints (18, 30) but are impaired for the repair of DNA double-strand breaks (25, 31) and are hypersensitive to ionizing radiation (31).

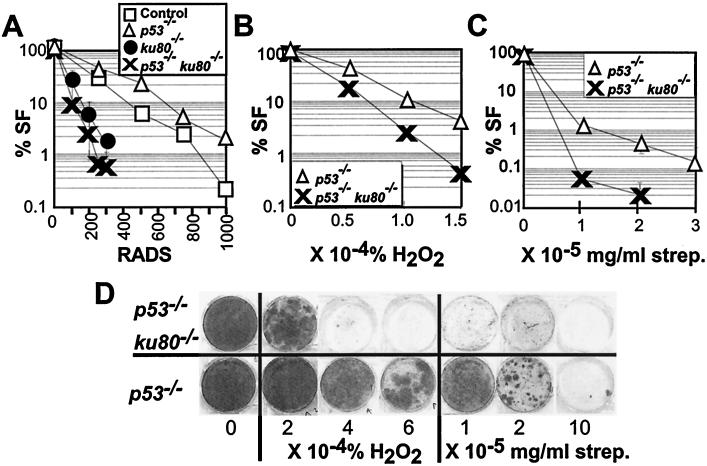

The effect of ionizing radiation on p53−/− ku80−/− MEF was determined for both checkpoint function (Fig. 5) and cell survival after exposure to genotoxic agents (Fig. 6). For ku80−/− cells, the G1/S (Fig. 5A and C), but not G2/M (Fig. 5B and C), checkpoint is dependent on p53. Even though deletion of p53 impairs the G1/S checkpoint and restores proliferation for ku80−/− cells, survival after exposure to γ-radiation does not improve (Fig. 6A). These data show that the double-mutant cells exhibit characteristics common to both mutations; that is, deletion of p53 impairs the G1/S checkpoint and deletion of Ku80 impairs survival after exposure to ionizing radiation.

FIG. 6.

Genotoxic analysis. (A to C) Dose-response curves to genotoxic agents. The percent survival fraction (% SF) is shown (100% × [the number of colonies exposed to genotoxic agent/the number of colonies not exposed to genotoxic agent]). Symbols are the same as in Fig. 1. (A) Dose response to γ-radiation. Graph depicts survival fraction when cells were plated at low density. The averages of clones are shown for control (n = 2), p53−/− (n = 3), ku80−/− (n = 2), and p53−/− ku80−/− (n = 2). (B) Dose response to H2O2. Graph depicts survival fraction when cells were plated at low density. A clone of p53−/− and p53−/− ku80−/− cells was analyzed. (C) Dose response to streptonigrin. Graph depicts survival fraction when cells were plated at high density. The averages of clones are shown for control p53−/− (n = 4) and p53−/− ku80−/− (n = 2) cells. (D) Dose response to H2O2 or streptonigrin for cells plated at high density. Shown are representative 3.5-cm-diameter wells that were originally plated with 2 × 105 cells and grown for 2 weeks before staining. Unexposed cells are shown at the left (labeled with a 0).

Spontaneous DNA damage caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS) has been proposed to be a causative factor of senescence (reviewed in references 1 and 27) and could stimulate p53-dependent replicative senescence in ku80−/− cells. Sensitivities of p53−/− ku80−/− MEF and p53−/− MEF to ROS were compared (Fig. 6B to D). These cells were exposed to either H2O2 or streptonigrin, a clastogenic compound that likely increases ·O2 (9). p53−/− ku80−/− cells are 10-fold more sensitive to 1.5 × 10−4% H2O2 (Fig. 6B and D) and are 54-fold more sensitive to 2 × 10−5 mg of streptonigrin/ml than p53−/− cells (Fig. 6C and D).

DISCUSSION

Survival curve and cancer incidence of ku80−/− mice deficient for p53.

Excluding environmental factors that cause death at any time, mortality is closely related to chronological age and is an important indicator of senescence (27). Age-specific mortality begins sometime after physical maturation and, in general, progresses at an accelerated rate. However, untrue to this general rule, the mortality rate for ku80−/− mice progressively decreases for the most long-lived 40% of the population. Previously, we proposed that this decrease in mortality rate may reflect low cancer incidence compared to that of the control cohort at a similar point in their survival curve (39). In support of this notion, the declining mortality rate observed for the most long-lived ku80−/− mice is reduced in a p53+/− background partly due to increased cancer incidence (20%).

The tumor spectrum for p53+/− ku80−/− mice is similar to that of p53+/− mice (21). Therefore, many ku80−/− cell types are capable of developing into cancer with diminished p53 levels. It is interesting that reduced levels of p53 do not substantially increase the incidence of lymphoma, unlike complete deletion of p53. This substantial increase in the incidence of pro-B-cell lymphoma, observed in p53−/− ku80−/− mice, is unlikely to be associated with senescence because of the very early onset (before or at the onset of physical maturation). Pro-B-cell malignancies also arise in young p53−/− scid mice (19, 29, 37). Most of these tumors carry recurrent chromosome translocations involving the IgH locus on chromosome 12, usually joined with chromosome 15 (37). Such oncogenic events may arise during attempted IgH rearrangement where rejoining of DNA is blocked by the scid mutation, a notion supported by the observation that the V(D)J endonuclease component Rag-2 is required for tumor development (19, 29, 37). A karyotype of one p53−/− ku80−/− tumor clearly showed a t(12;15) with breakpoints similar to those observed in p53−/− scid mice pro-B-cell tumors (19, 29, 37), suggesting that susceptibility to such translocations is conferred by unjoined DNA coding ends coupled with defective cell cycle checkpoints or programmed cell death as previously proposed (19, 29, 37).

Onset of cancer was earlier for p53+/− ku80−/− mice than for p53+/− mice. About 20% of p53+/− ku80−/− mice died from cancer by 40 weeks, compared to about 4% of p53+/− mice (21). Since onset of cancer is earlier in the p53+/− ku80−/− cohort than in the p53+/− cohort, one could argue that deletion of Ku80 increased cancer incidence for the p53+/− mice due to inefficient DNA repair. However, this argument is compromised by the observation that there is little alteration in tumor spectrum. A disproportionate increase in risk of lymphoma would be expected if deletion of Ku80 actually increased cancer risk in p53+/− mice because ku80−/− lymphocytes are known to maintain open coding ends (40) and because lymphoma is so pervasive in p53−/− ku80−/− mice. Thus, inefficient repair of DNA double-strand breaks does not appear to increase cancer risk in p53+/− mice.

Cancer incidence over the entire life span was reduced for the p53+/− ku80−/− population compared to that of the p53+/− population. Reduced cancer incidence may simply be a consequence of the shortened life span of the p53+/− ku80−/− cohort compared to that of the p53+/− cohort. Alternatively, cancer incidence may be reduced due to early onset of senescence caused by deletion of Ku80. To support this hypothesis, p53+/− ku80−/− mice exhibit an early onset of a variety of age-related characteristics, including epiphysis closure, osteopenia, and skin atrophy. The proportion of the population that exhibits these characteristics is about the same as that of control mice even though these characteristics are not observed until after the natural life span of the p53+/− ku80−/− population. Cancer is another age-related disease observed earlier in p53+/− ku80−/− mice than in p53+/− mice; however, unlike the other age-related characteristics, many fewer p53+/− ku80−/− mice develop cancer.

Replicative senescence and cancer.

Based on the mortality curve, cancer incidence, and cellular proliferation data, predictions can be made about Ku80 and p53 that support the hypothesis that replicative senescence protects an organism against cancer (review in reference 7). Analysis of p53+/− ku80−/− cells and mice may uniquely address this hypothesis, because both cells and mice exhibit phenotypic characteristics common to mutations of p53 and ku80. Analysis of cells by the cross-sectional CSD shows that p53+/− ku80−/− cells exhibit reduced proliferation potential throughout the animal's life span, similar to the ku80−/− phenotype. However, the 3T3 equivalent analysis and its companion CSD show that p53+/− ku80−/− cells spontaneously immortalize when propagated in tissue culture, similar to the p53−/− phenotype. Analysis of mice shows the p53+/− ku80−/− cohort exhibits an early onset of senescence, similar to the ku80−/− phenotype; however, tumor spectrum and incidence (albeit lower) is more similar to the p53−/− phenotype. Thus, it is possible that the p53+/− ku80−/− cells undergo premature replicative senescence that reduces cancer risk (due to deletion of Ku80), but ultimately in some mice, reduced levels of p53 compromise replicative senescence and stimulate cancer.

The cell cycle and genotoxic analyses suggest a mechanism for replicative senescence in ku80−/− cells, that is, a p53-dependent G1/S response to spontaneous ROS-induced DNA damage that requires Ku80 for efficient repair. This hypothesis is supported by the following observations. (i) Deletion of p53 restored proliferative potential to ku80−/− cells. (ii) Deletion of p53 ablated the G1/S cell cycle checkpoint in ku80−/− cells. (iii) Deletion of p53 did not improve resistance to γ-irradiation for ku80−/− cells. Therefore, p53 is essential for replicative senescence in ku80−/− cells and, assuming that spontaneous DNA damage still occurs in the double-mutant cells, DNA damage is not essential for replicative senescence.

Replicative senescence and organismic senescence?

These data support the free radical hypothesis by Harman which states that accumulation of ROS-induced DNA damage is a component of organismic senescence (20), with the modification that cell cycle checkpoints are essential (review in reference 7). However, more analysis is important to determine if this p53-dependent mechanism of replicative senescence takes part in organismic senescence. It is disappointing that p53−/− ku80−/− mice do not live long enough to address this issue. A future experiment would be to conditionally mutate p53 in skin, bone, or liver, but not lymphoid cells of ku80−/− mice. These ku80−/− mice, with wild-type levels of p53 in lymphoid cells, could be evaluated for senescence in the tissue with deleted p53.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Larry Donehower for sharing unpublished data; Molly A. Bogue, David B. Roth, Mariana Yaneva, and Brian Zambrowicz for critical review of the manuscript; Sayadeth Khounlo, Ana Sanchez, Shirley Jackson, Darrin Shiver, Wendy Schober, and Stefan Spath for technical assistance; Christine Disteche for performing the karyotype analysis; and Molly A. Bogue for performing the flow cytometric tumor analysis.

This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (1RO1CA76317-01 to P.H. and 1RO1CA88075-01 to D.M.W.) and by Lexicon Genetics Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bernstein C, Bernstein H. Aging, sex, and DNA repair. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biedermann K A, Sun J, Giaccia A J, Tosto L M, Brown M. scid mutation in mice confers hypersensitivity to ionizing radiation and deficiency in DNA double-strand break repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1394–1397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.4.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bogue M A, Wang C, Zhu C, Roth D B. V(D)J recombination in Ku86-deficient mice: distinct effects on coding, signal, and hybrid joint formation. Immunity. 1997;7:37–47. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80508-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bogue M A, Zhu C, Aguilar-Cordova E, Donehower L A, Roth D B. p53 is required for both radiation-induced differentiation and rescue of V(D)J rearrangement in scid mouse thymocytes. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1–13. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.5.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bond J A, Haughton M F, Rowson J M, Smith P J, Gire V, Wynford-Thomas D, Wyllie F S. Control of replicative life span in human cells: barriers to clonal expansion intermediate between M1 senescence and M2 crisis. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3103–3114. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braylan R C, Benson N A, Nourse V, Kruth H S. Correlated analysis of cellular DNA, membrane antigens and light scatter of human lymphoid cells. Cytometry. 1982;2:337–343. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990020511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campisi J. Aging and cancer: the double-edged sword of replicative senescence. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:482–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb05175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campisi J, Dimri G, Hara E. Control of replicative senescence. In: Schneider E L, Rowe J W, editors. Handbook of the biology of aging. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1996. pp. 121–149. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen M M, Shaw M W, Craig A P. The effects of streptonigrin on cultured human leukocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1963;50:16–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.50.1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Custer R P, Bosma G C, Bosma M J. Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) in the mouse. Am J Pathol. 1985;120:464–477. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Vries E, van Driel W, Bergsma W G, Arnberg A C, van der Vliet P C. HeLa nuclear protein recognizing DNA termini and translocating on DNA forming a regular DNA-multimeric protein complex. J Mol Biol. 1989;208:65–78. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donehower L A, Harvey M, Slagle B L, McArthur M J, Montgomery C A J, Butel J S, Bradley A. Mice deficient for p53 are developmentally normal but susceptible to spontaneous tumours. Nature. 1992;356:215–221. doi: 10.1038/356215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elledge S J. Cell cycle checkpoints: preventing an identity crisis. Science. 1996;274:1664–1672. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Errami A, Smider V, Rathmell W K, He D M, Hendrickson E A, Zdzienicka M Z, Chu G. Ku86 defines the genetic defect and restores x-ray resistance and V(D)J recombination to complementation group 5 hamster cell mutants. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1519–1526. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fulop G M, Phillips R A. The scid mutation in mice causes a general defect in DNA repair. Nature. 1990;347:479–482. doi: 10.1038/347479a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao Y, Sun Y, Frank K M, Dikkes P, Fujiwara Y, Seidl K J, Sekiguchi J M, Rathburn G A, Swat W, Wang J, Bronson R T, Malynn B A, Bryans M, Zhu C, Chaudhuri J, Davidson L, Ferrini R, Stamato T, Orkin S H, Greenberg M E, Alt F W. A critical role for DNA end-joining proteins in both lymphogenesis and neurogenesis. Cell. 1998;95:891–902. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81714-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gu Y, Jin S, Gao Y, Weaver D T, Alt F W. Ku70-deficient embryonic stem cells have increased ionizing radiosensitivity, defective DNA end-binding activity, and inability to support V(D)J recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8076–8081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.8076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gu Y, Seidl K J, Rathbun G A, Zhu C, Manis J P, van der Stoep N, Davidson L, Cheng H-L, Sekiguchi J M, Frank K, Stanhope-Baker P, Schlissel M S, Roth D B, Alt F W. Growth retardation and leaky SCID phenotype of Ku70-deficient mice. Immunity. 1997;7:653–665. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80386-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guidos C J, Williams C J, Grandal I, Knowles G, Huang M T F, Danska J S. V(D)J recombination activates a p53-dependent DNA damage checkpoint in scid lymphocyte precursors. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2038–2054. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.16.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harman D. Aging: a theory based on free radical and radiation chemistry. J Gerontol. 1956;11:298–300. doi: 10.1093/geronj/11.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harvey M, McArthur M J, Montgomery C A, Butel J, Bradley A, Donehower L A. Spontaneous and carcinogen-induced tumorigenesis in p53-deficient mice. Nat Gen. 1993;5:225–229. doi: 10.1038/ng1193-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harvey M, Sands A T, Weiss R S, Hegi M E, Wiseman R W, Pantazis P, Giovanella B C, Tainsky M A, Bradley A, Donehower L A. In vitro growth characteristics of embryo fibroblasts isolated from p53-deficient mice. Oncogene. 1993;8:2457–2467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayflick L. The limited in vitro lifetime of human diploid cell strains. Exp Cell Res. 1965;37:614–636. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(65)90211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ko L, Prives C. p53: puzzle and paradigm. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1054–1072. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.9.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang F, Romanienko P J, Weaver D T, Jeggo P A, Jasin M. Chromosomal double-strand break repair in Ku80-deficient cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8929–8933. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.8929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lieber M R. Pathological and physiological double-strand breaks: roles in cancer, aging and the immune system. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:1323–1332. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65716-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masoro E J. Aging: current concepts. In: Masoro E J, editor. Handbook of physiology. Vol. 11. New York, N.Y: American Physiological Society by Oxford University Press; 1995. pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mimori T, Hardin J A. Mechanism of interaction between Ku protein and DNA. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:10375–10379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nacht M, Strasser A, Chan Y R, Harris A W, Schlissel M, Bronson R T, Jacks T. Mutations in the p53 and SCID genes cooperate in tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2055–2066. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.16.2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nussenzweig A, Chen C, da Costa Soares C, Sanchez M, Sokol K, Nussenzweig M C, Li G C. Requirement for Ku80 in growth and immunoglobulin V(D)J recombination. Nature. 1996;382:551–555. doi: 10.1038/382551a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ouyang H, Nussenzweig A, Kurimasa A, da Costa Soares V, Li X, Cordon-Cardo C, Li W-h, Cheong N, Nussenzweig M, Iliakis G, Chen D J, Li G C. Ku70 is required for DNA repair but not for T cell antigen receptor gene recombination in vivo. J Exp Med. 1997;186:921–929. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.6.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smider V, Rathmell W K, Lieber M R, Chu G. Restoration of X-ray resistance and V(D)J recombination in mutant cells by Ku cDNA. Science. 1994;266:288–290. doi: 10.1126/science.7939667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith G C M, Jackson S P. The DNA-dependent protein kinase. Genes Dev. 1999;13:916–934. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.8.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith J R, Pereira-Smith O M, Schneider E L. Colony size distributions as a measure of in vivo and in vitro aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:1353–1356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.3.1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taccioli G E, Gottlieb T M, Blunt T, Priestley A, Demengeot J, Mizuta R, Lehmann A R, Alt F W, Jackson S P, Jeggo P A. Ku80: product of the XRCC5 gene and its role in DNA repair and V(D)J recombination. Science. 1994;265:1442–1445. doi: 10.1126/science.8073286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Timme T L, Thompson T C. Rapid allelotype analysis of p53 knockout mice. BioTechniques. 1994;17:462–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vanasse G J, Halbrook J, Thomas S, Burgess A, Hoekstra M F, Disteche C M, Willerford D M. Genetic pathway to recurrent chromosome translocations in murine lymphoma involves V(D)J recombinase. J Clin Investig. 1999;103:1669–1675. doi: 10.1172/JCI6658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Venkatachalam S, Shi Y P, Jones S N, Vogel H, Bradley A, Pinkel D, Donehower L A. Retention of wild-type p53 in tumors from p53 heterozygous mice: reduction of p53 dosage can promote cancer formation. EMBO J. 1998;17:4657–4667. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vogel H, Lim D S, Karsenty G, Finegold M, Hasty P. Deletion of Ku86 causes early onset of senescence in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;19:10770–10775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu B, Bogue M A, Lim D-S, Hasty P, Roth D B. Ku86-deficient mice exhibit severe combined immunodeficiency and defective processing of V(D)J recombination intermediates. Cell. 1996;86:379–389. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]