This qualitative study surveys otolaryngologists and radiation oncologists regarding their opinions on deintensification of surveillance in patients with diagnosed head and neck cancer.

Key Points

Question

What are otolaryngologists’ and radiation oncologists’ perspectives on deintensifying head and neck cancer surveillance?

Findings

In this qualitative study of 21 otolaryngologists and radiation oncologists, clinicians identified potential barriers to deintensifying surveillance, including patient and physician peace of mind, need to maintain a physician-patient relationship, and need to adequately manage treatment-associated toxic effects and other survivorship concerns.

Meaning

These findings suggest that incorporation of surveillance and survivorship education in training, positive reframing of surveillance deintensification, and creation of virtual survivorship programs may address some barriers to deintensification.

Abstract

Importance

Surveillance imaging and visits are costly and have not been shown to improve oncologic outcomes for patients with head and neck cancer (HNC). However, the benefit of surveillance visits may extend beyond recurrence detection. To better understand surveillance and potentially develop protocols to tailor current surveillance paradigms, it is important to elicit the perspectives of the clinicians who care for patients with HNC.

Objective

To characterize current surveillance practices and explore clinician attitudes and beliefs on deintensifying surveillance for patients with HNC.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This qualitative study was performed from January to March 2021. Guided by an interpretive description approach, interviews were analyzed to produce a thematic description. Data analysis was performed from March to April 2021. Otolaryngologists and radiation oncologists were recruited using purposive and snowball sampling strategies.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The main outcomes were current practice, attitudes, and beliefs about deintensifying surveillance and survivorship as well as patients’ values and perspectives collected from interviews of participating physicians.

Results

Twenty-one physicians (17 [81%] men) were interviewed, including 13 otolaryngologists and 8 radiation oncologists with a median of 8 years (IQR, 5-20 years) in practice. Twelve participants (57%) stated their practice comprised more than 75% of patients with HNC. Participants expressed that there was substantial variation in the interpretation of the surveillance guidelines. Participants were open to the potential for deintensification of surveillance or incorporating symptom-based surveillance protocols but had concerns that deintensification may increase patient anxiety and shift some of the burden of recurrence monitoring to patients. Patient and physician peace of mind, the importance of maintaining the patient-physician relationship, and the need for adequate survivorship and management of treatment-associated toxic effects were reported to be important barriers to deintensifying surveillance.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this qualitative study, clinicians revealed a willingness to consider altering cancer surveillance but expressed a need to maintain patient and clinician peace of mind, maintain the patient-clinician relationship, and ensure adequate monitoring of treatment-associated toxic effects and other survivorship concerns. These findings may be useful in future research on the management of posttreatment surveillance.

Introduction

Improvements in overall survival and the increasing incidence of human papilloma virus (HPV)–positive oropharyngeal cancer have resulted in an increase in the population of survivors of head and neck cancer (HNC) in the US.1 The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines provide broad recommendations for HNC that do not risk stratify patients by clinical characteristics, such as HPV infection status or site.2 The guidelines recommend surveillance visits every 1 to 3 months during the first year, 2 to 6 months during the second year, 4 to 8 months during years 3 to 5, and annually thereafter. Posttreatment imaging is recommended within 6 months of treatment for patients with locoregionally advanced disease. Although the guidelines provide a broad overview, current surveillance practices have been shown to be highly variable among clinicians.3,4,5

Studies have demonstrated that routine visits and imaging are costly and do not provide a survival advantage for patients with HNC.3,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 Furthermore, most recurrences are diagnosed based on symptoms rather than on examination findings for asymptomatic patients.7,9,10,11 Patient surveys have suggested that many would prefer decreasing the frequency of surveillance visits,14 and those who experience financial toxicity are less likely to be adherent to recommended follow-up and treatment.15 In light of this information, studies have suggested risk-stratifying surveillance and deintensifying regimens for patients with low risk of recurrence, particularly those with HPV-associated disease.10,11 However, the value of surveillance visits to clinicians may extend beyond recurrence detection and include survivorship care as well as enhancement of the patient-physician relationship.

To better understand HNC surveillance and potentially develop protocols to tailor the current surveillance paradigm, it is important to understand the perspectives of the clinicians who provide care for patients with HNC with respect to surveillance. The purpose of our study was to characterize current surveillance practices and explore clinician attitudes and beliefs on deintensifying surveillance.

Methods

For this qualitative study, we conducted semistructured interviews with clinicians whose specialty was HNC throughout the US from January to March 2021 through video conferencing (Zoom; Zoom Videocommunications). Eligible participants were otolaryngologists or radiation oncologists who treated patients with HNC. Participants were recruited via email from a personal and professional network. Purposive sampling was used to focus on clinicians with varying experience levels, proportions of patients with HNC in their practices, case volumes, and practice types. We then used snowball sampling by asking each participant for referrals of other clinicians who treated patients with HNC to recruit additional participants. The study was determined to be exempt from review by the University of Michigan institutional review board because it involved only interview procedures and the information recorded was deidentified. All participants verbally consented to be interviewed and were offered a $25 gift card as an incentive. This study followed the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) guideline.

The semistructured interview guide (eAppendix in the Supplement) was developed iteratively in collaboration with subject and methodologic experts. We conducted 1 pilot interview with a clinician who met study eligibility criteria and whose feedback informed slight modifications to the subsequent interview guide. The pilot interview was not included in the results. In brief, participants were asked about their current practice, attitudes and beliefs about deintensifying surveillance, views on survivorship, and patients’ values and perspectives. In addition, a demographic survey was administered to obtain information on years of practice, volume of HNC cases, and new patient volume.

Two interviewers (M.M.C. and N.M.M.) trained in qualitative methods conducted all interviews. Interviews were audiorecorded, transcribed verbatim, and deidentified. We followed the inductive and iterative approach of interpretive description, a qualitative method that interprets participants’ subjective experiences to improve understanding of clinical issues.16 We used information power to estimate and assess the sample size.17 This assessment was guided by the fact that the study aim was narrow, the sample was dense, and the quality of the dialogue was strong and clear. Transcripts were imported to MAXQDA, version 2020 software (VERBI Software) to support coding and analysis. The research team developed a codebook that contained structural and descriptive codes deductively applied for each question. These codes were later supplemented by inductively derived codes descriptive of factors volunteered by the participants. Each interview was coded independently by 2 researchers (M.M.C. and N.M.M.). The coding was discussed at weekly team meetings, and any differences in the researchers’ coding were resolved through discussion until a consensus was met. Constant comparison was used to refine the coding taxonomy.18

We used data abstraction, case comparison, and memo writing to focus and develop our themes. We retrospectively applied the Theoretical Domains Framework to systematically group our themes into domains.19 The Theoretical Domains Framework is an integrated theoretical framework that is used in health behavior change and implementation research. These domains were also mapped to the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, and Behavior Model components.20 This model is used to evaluate how components of capability, opportunity, and motivation interact with behavior and can be used to identify potential targets for behavioral interventions.20 To address trustworthiness, we also discussed alternative interpretations, biases, latent themes, prevalence, outliers, and the clinical implications of our findings in regular meetings. Data analysis was performed from March to April 2021.

Results

Study Participants

Twenty-one physicians were interviewed, including 13 otolaryngologists and 8 radiation oncologists (Table 1). Of these, 17 were men (81%) and 4 were women (19%). The median time in practice was 8 years (IQR, 5-20 years); 11 physicians (52%) had less than 10 years of experience, and 10 physicians (48%) had 10 or more years of experience. Most clinicians (19 [90%]) practiced in an academic setting, and 12 individuals (57%) stated that patients with HNC comprised more than 75% of their practice.

Table 1. Participant Demographic Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Participants, No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 4 (19) |

| Male | 17 (81) |

| Specialty | |

| Otolaryngology | 13 (62) |

| Radiation oncology | 8 (38) |

| Region | |

| East | 3 (14) |

| Midwest | 14 (67) |

| West | 3 (14) |

| South | 2 (10) |

| Experience | |

| Median (IQR), y | 8 (5-20) |

| <10 y in practice | 11 (52) |

| ≥10 y in practice | 10 (48) |

| Practice setting | |

| Academic | 19 (90) |

| Community | 2 (10) |

| Head and neck cancer case volumea | |

| ≤50% | 4 (19) |

| 51%-75% | 5 (24) |

| >75% | 12 (57) |

| New patient volumeb | |

| <100 | 5 (24) |

| 100-150 | 8 (38) |

| >150 | 7 (33) |

| Unknown | 1 (5) |

Defined as annual percentage of patients with head and neck cancer.

Defined as annual number of new patients with head and neck cancer.

Current Surveillance Practice

Clinicians reported a varied frequency of surveillance visits, ranging from every 6 weeks to every 4 months for the first 2 years and then every 3 to 6 months until 5 years after treatment. After 5 years, some clinicians evaluated patients annually, and others recommended them to be seen only as needed. Clinicians would often alternate visits between otolaryngology (head and neck surgical oncology trained) and radiation oncology but were more reluctant to alternate surveillance visits with local general otolaryngologists and primary care physicians. Many performed endoscopic examinations at each surveillance visit; the remainder varied based on the clinical scenario (eg, disease site, stage of tumor, and patient risk factors) and increased the interval between endoscopic examinations over time or performed mirror examinations. Clinicians also discussed performing only mirror examinations and not routinely performing endoscopic examinations for patients with oral cavity sites unless the patient smoked, was symptomatic, or had a difficult mirror examination.

Most participants obtained a 3-month posttreatment computed tomography neck and chest scan or a positron emission tomography scan and no further routine imaging unless prompted by symptoms or clinical concern. Many participants discussed previously having obtained routine annual imaging but did not find benefit and had since limited routine scanning to 1 posttreatment scan. The remainder of clinicians obtained images routinely every 6 to 12 months. Many clinicians also reported routinely obtaining annual low-dose chest computed tomography scans for all patients who smoked.

Guidelines

All participants were aware of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines but reported that the broad nature of the guidelines often led to variation in their practice. Many approached the guidelines as a suggested practice but discussed perceived room for interpretation based on clinical judgment. Several clinicians discussed a lack of substantial evidence supporting the guidelines with respect to surveillance visits, imaging, and endoscopic examinations. Clinicians stated that their current or past institutional culture often influenced their practice patterns.

Physician-Level Factors

Participants expressed mixed feelings about deintensifying cancer surveillance. In general, clinicians with 10 or more years of experience had favorable attitudes and beliefs about deintensifying surveillance, stating that in their experience, recurrences were commonly associated with symptoms and a more flexible surveillance schedule was more patient-centered. Participants were also more comfortable with symptom-based surveillance after the first 2 to 3 years for select patients, such as those with HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer and older individuals or those with substantial financial or travel burdens and low-risk disease. Clinicians spoke of their personal clinical experience and the rarity of detecting a recurrence during physical examination of an asymptomatic patient. However, participants acknowledged that standardization across all patients and having a more consistent algorithm was easier to incorporate into clinical workflows. A few participants discussed a preference to have more data guiding their decision-making to risk-stratify patients (Table 2).

Table 2. Theoretical Domains Framework for Behavior Change Mapped to Clinician-Level Factors With Exemplary Quotesa.

| Domain and theme | Sample quote (participant identifier, clinician specialty) |

|---|---|

| Knowledge | |

| Clinical experience leads to more comfort with deintensification |

|

| Clinician training and inertia in practice patterns |

|

| Skills | |

| Endoscopic examinations are a specialized skill |

|

| Clinicians’ discomfort addressing survivorship |

|

| Decision | |

| Standardization is easier |

|

| Social and professional role and identity | |

| Uncertainty in who is managing survivorship |

|

| Beliefs about capabilities | |

| Trust in local otolaryngologists |

|

| Reinforcement | |

| Importance of financial incentives |

|

| Fear of litigation |

|

| Emotion | |

| Clinician anxiety and need for peace of mind |

|

| Preservation of patient-physician relationship |

|

The Theoretical Domains Framework is an integrated theoretical framework that is used in health behavior change and implementation research.19

Clinicians with less than 10 years of experience were less supportive of altering surveillance. They specifically cited factors including concern about missing recurrences or not detecting recurrences early enough and the need for frequent visits for close monitoring of treatment-associated toxic effects. Some participants were more comfortable with considering altering surveillance 2 or more years after treatment. Participants stated that some of this discomfort may be owing to being both risk averse and early in their career. They also stated that their practice reflected their experience in training and discussed habit or a sense of inertia as barriers to changing their current practice. Concerns about symptom-based surveillance centered on the need for more data on using quality-of-life questionnaires and telemedicine as the primary metrics for aiding symptom-based surveillance and detecting concern for recurrence. In addition, clinicians expressed worry that symptom-based surveillance may increase patient anxiety and require more patient education and reassurance; in addition, they were concerned about patient reliability in reporting symptoms and missing recurrences.

Clinicians reported that maintaining a patient-physician relationship was one of the most important and fulfilling aspects of providing care for patients with HNC. Many discussed a psychosocial advantage of maintaining that relationship through surveillance visits even if they did not alter the rate of detection of recurrences. Clinicians highly valued the long-term relationship and trust with their patients and did not want to give up that aspect of their practice.

The value of alternating with local general otolaryngologists or radiation oncologists was commonly acknowledged as a benefit especially for patients with financial or travel concerns. However, factors that influenced willingness to alternate with local clinicians included their trust and relationship with the clinician regardless of whether the local clinician performed endoscopic or mirror examinations and a desire to follow up with patients in their care regularly to have context for changes in examination findings. Clinicians rarely alternated visits with local medical oncologists. Clinicians were more willing to alternate visits with local primary care physicians 5 or more years after treatment when the focus was more on survivorship than on surveillance.

Patient-Level Factors

Most clinicians suggested that specific patient groups with lower risk of recurrence, such as those with HPV-associated disease, could benefit from deintensified surveillance. Some also suggested that deintensification would be most helpful for patients at low risk who found frequent visits to be a hardship, such as older patients, those with a substantial travel burden, or those with limited finances or resources (Table 3). Patient reliability in reporting new symptoms was also an important factor to clinicians when thinking about deintensifying surveillance. Clinicians expressed concern about deintensifying surveillance for individuals who smoked, those without HPV infection, and patients with HNC sites in which symptoms of recurrence are less likely to arise early, such as the hypopharynx.

Table 3. Theoretical Domains Framework for Behavior Change Mapped to Patient- and System-Level Factors With Exemplary Quotesa.

| Domain and theme | Sample quote (participant identifier, clinician specialty) | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient level | ||

| Social and professional role and identity | ||

| Patient expectations for their clinicians |

|

|

| Behavioral regulation | ||

| Patient education modulates expectations |

|

|

| Beliefs about capabilities | ||

| Patient reliability concerns |

|

|

| Social influences | ||

| Patient travel and financial concerns |

|

|

| Lack of patient support system |

|

|

| Emotion | ||

| Patient anxiety and need for peace of mind |

|

|

| Preservation of the patient-physician relationship |

|

|

| System level | ||

| Knowledge | ||

| Lack of evidence supporting current guidelines |

|

|

| Lack of evidence supporting current practice |

|

|

| Environmental context and resources | ||

| Surveillance and survivorship are linked |

|

|

| Telemedicine has a limited role |

|

|

Abbreviations: HPV, human papilloma virus; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; PET, positron emission tomography.

The Theoretical Domains Framework is an integrated theoretical framework that is used in health behavior change and implementation research.19

Patients’ need for peace of mind was described as a barrier to deintensifying surveillance. Clinicians described scheduling more frequent visits or ordering scans even when not clinically indicated to address patient anxiety. With the current gradual lengthening of surveillance intervals, participants believed patients still had substantial concerns about decreasing the visit frequency owing to fear of recurrence. Participants stated that more symptom-driven surveillance may increase patient anxiety and may transfer to patients the psychological burden of monitoring their symptoms. In general, clinicians stated that patients expect physicians to provide guidance on surveillance expectations. Some reported that patient education on risk of recurrence and setting expectations about surveillance may reassure patients and alleviate patient anxiety about altered surveillance.

System-Level Factors

Most clinicians had used some form of telemedicine as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Clinicians reported using telemedicine as a screening visit or triage tool, a way to alternate with in-person visits, for symptom management and survivorship, in conjunction with in-person visits with a local clinician, or for symptom follow-up for patients receiving palliative care. Some clinicians did not think they would continue to incorporate telemedicine heavily in their surveillance practice after the pandemic owing to the inability to perform physical and endoscopic examinations in the virtual format, potential lack of continuing reimbursement, or uncertainty of how telemedicine fits in their typical practice. Participants noted that when offered virtual visits, many patients preferred in-person visits.

Clinicians acknowledged that surveillance and survivorship have different goals but that in the current paradigm, surveillance visits and intervals were often used to address both surveillance for disease recurrence and management of treatment-associated toxic effects and other survivorship concerns. Owing to the linkage of survivorship and surveillance, clinicians suggested that the current practice may lead to unnecessary surveillance (“over-surveilling”) but a lack of attention to survivorship concerns (“under-survivorshipping”) of patients with HNC. Many clinicians discussed feeling they did not have the tools or time to adequately manage the wide range of survivorship issues, particularly psychosocial issues such as depression, social intimacy, and body image concerns.

Discussion

This qualitative study explored clinicians’ current surveillance practices for patients with HNC and their attitudes and beliefs about tailoring surveillance strategies in the future. Participants expressed that there was much room for interpretation of the current guidelines. Clinicians were open to the potential for deintensifying surveillance or incorporating symptom-based surveillance but had concerns that deintensifying may increase anxiety and shift some of the burden of recurrence monitoring to patients. Peace of mind, maintenance of the patient-physician relationship, and the need for adequate survivorship and management of treatment-associated toxic effects were important barriers to altering surveillance (Box).

Box. Barriers and Facilitators for Deintensifying Head and Neck Cancer Surveillance.

Barriers

Clinician level

Less than 10 years in practice

Importance of examination and flexible laryngoscopy

Desire for standardized protocol

Desire to be actively involved in a patient's cancer care and variable trust in local clinicians

Need for peace of mind and concern for recurrence and second primary tumors

Maintenance of patient-physician relationship

Financial incentives

Fear of litigation

Patient level

Expectation for routine surveillance

Need for peace of mind and anxiety about recurrence

Reliability, travel and financial concerns, and lack of support network

High-risk disease (eg, advanced-stage disease, disease in persons who smoke tobacco)

Maintenance of patient-physician relationship

System level

Need for more research

Limited use of telemedicine for surveillance examinations

Surveillance visits linked to survivorship visits

Facilitators

Clinician level

Ten years or more in practice

Recurrences less likely to be noted in examinations of asymptomatic patients

Recognition of different risk factors and needs of patients

Established relationships with local clinicians and primary care physicians

Patient level

Patient education about surveillance needs

Patient education about risk of recurrence

Ancillary services and a strong support network

Low-risk disease (eg, low-stage disease, human papilloma virus–associated disease, and disease in persons who do not smoke tobacco)

System level

Lack of evidence supporting current guidelines and practice

Increased use of telemedicine for symptom screening

Despite awareness of the guidelines, nearly half of the participants obtained routine surveillance imaging and expressed that the recommendations about surveillance visits were broad and left room for variability. Roman et al5 reported that, even among clinicians who were aware of the surveillance imaging guidelines, 31% ordered surveillance positron emission tomography scans more than 50% of the time for asymptomatic patients. On multivariable analysis in that study, there was no association between specialty, physician sex, years in practice, practice settings, or HNC case volume and increased use of imaging.

A key emergent theme in our study was the importance of peace of mind in influencing the intensity of cancer surveillance. Patients’ and clinicians’ need for peace of mind have been shown to be associated with overtreatment for other cancers, including prostate,21 thyroid,22 breast,23 and ovarian.24 Physicians in general are trained to be relatively intolerant of uncertainty and error.25,26 In our study, clinicians with fewer years in practice expressed concerns about deintensification owing to fear of recurrence and also referenced that their practice may change as they advance in their careers. The longer clinicians were practicing, the more likely they were to express favorable attitudes about deintensification because of their personal clinical experience and increased trust with local physicians.

For patients, emotional responses to cancer treatment may lead to choices not necessarily in their best interest.27 Patients’ preferences are sensitive to how options are framed by their physician, and education can help improve tolerance of uncertainty, assuage patient concerns, and provide peace of mind.28 Because most recurrences are identified on the basis of patient symptoms,7,10,11 positive reframing of symptom-based surveillance may empower patients rather than cause anxiety and may improve patient reliability and early detection. In a survey of patients with low-risk oropharyngeal cancer, 55.2% patients were interested in decreased frequency of in-clinic surveillance visits.14 This proportion increased to 61.2% after education about the low risk of recurrence.14 Patient-level factors that were associated with decreased interest in deintensification included being a medical maximizer (individuals who prefer to take an active approach to health care and may want to receive optional medical tests and treatments), having a long-term relationship with the physician, and having higher worry of cancer recurrence.14

Maintaining the patient-physician relationship was valued by clinicians and was another important barrier to reduced surveillance. The need to maintain this relationship had already resulted in reluctance to alternate surveillance with local otolaryngologists, radiation oncologists, or primary care physicians. Brennan et al29 surveyed 175 patients with HNC and reported that 79.4% preferred to continue to see their oncologist rather than have follow-up with their family physician (85.7%) or exclusively by a clinic nurse (90.3%). However, despite the value clinicians placed in the patient-physician relationship, they acknowledged the travel and financial burden of frequent surveillance for patients and expressed discomfort in addressing the wide range of survivorship issues, particularly psychosocial concerns. This discomfort suggests that, although sympathetic to the patient perspective, clinicians may have viewed the patient-physician relationship through a clinician-centered lens, and a more patient-centered view may allow for more-tailored surveillance schedules.

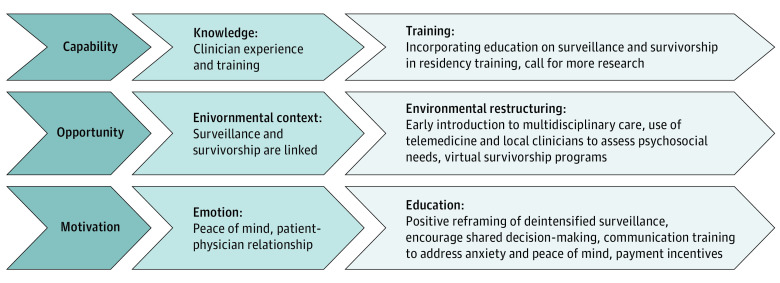

Potential interventions could be focused on the knowledge, emotion, and environmental context domains (Figure). To address knowledge, more education about surveillance and survivorship could be incorporated into residency and fellowship training so that trainees develop comfort with managing follow-up and have less fear and uncertainty when they start their own clinical practice. Research could investigate the utility of payment incentives for incorporating multidisciplinary survivorship care or patient-centered outcomes in survivorship care. For the emotion domain, positive reframing of deintensified surveillance to patients may help with patient anxiety about deintensification. Communication training may provide clinicians with strategies to actively address patient anxiety and peace of mind other than with additional imaging. Shared decision-making may lead to more patient-centered discussions of surveillance by encouraging team talk of surveillance options with the use of decision aids when possible and may help physicians focus in aiding patients in exploring and forming their personal preferences.30 In addition, in the current environment, surveillance and survivorship provision are linked during routine follow-up visits, resulting in an overuse of surveillance and underuse of survivorship.31 Restructuring of this environment by continuing in-person surveillance with surgeons and radiation oncologists and also using telemedicine and virtual care to manage symptoms and create virtual survivorship programs may improve the balance between surveillance and survivorship.

Figure. Proposed Interventions Based on the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, and Behavior Model and the Theoretical Domains Framework for Behavior Change.

The Theoretical Domains Framework is an integrated theoretical framework that is used in health behavior change and implementation research.19 The Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, and Behavior Model is used to evaluate how components of capability, opportunity, and motivation interact with behavior and can be used to identify potential targets for behavioral interventions.20

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, selection bias was possible. Most clinicians had primarily head and neck–focused practices and worked at academic medical centers; thus, they may have been more comfortable with deintensifying surveillance. We also did not interview patients; therefore, we did not have data on patient preferences. However, prior work has suggested that patients experience a significant travel and financial burden with surveillance visits, and more than half were interested in decreasing the frequency of surveillance visits.14 The background and theoretical orientation of the research team may also have affected the results if participants shared only thoughts that they felt the team wanted to hear.

Conclusions

This qualitative study explored clinician perspectives about surveillance of patients with HNC and the potential for deintensification. Clinicians revealed a willingness to consider altering cancer surveillance but expressed a need to maintain patient and clinician peace of mind, maintain the patient-clinician relationship, and ensure that there still was adequate monitoring of treatment-associated toxic effects and other survivorship concerns. These findings might be used to guide future research in the management of posttreatment surveillance and survivorship, specifically through a surveillance deintensification implementation trial and a cost analysis of altering surveillance.

eAppendix. Interview Guide

References

- 1.Patel MA, Blackford AL, Rettig EM, Richmon JD, Eisele DW, Fakhry C. Rising population of survivors of oral squamous cell cancer in the United States. Cancer. 2016;122(9):1380-1387. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . Head and neck cancers, version 2. 2017. Accessed June 12, 2021. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/head-and-neck.pdf

- 3.Schwartz DL, Barker J Jr, Chansky K, et al. Postradiotherapy surveillance practice for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma—too much for too little? Head Neck. 2003;25(12):990-999. doi: 10.1002/hed.10314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tam S, Nurgalieva Z, Weber RS, Lewis CM. Adherence with National Comprehensive Cancer Network posttreatment surveillance guidelines in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2019;41(11):3960-3969. doi: 10.1002/hed.25936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roman BR, Patel SG, Wang MB, et al. Guideline familiarity predicts variation in self-reported use of routine surveillance PET/CT by physicians who treat head and neck cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13(1):69-77. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2015.0010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooney TR, Poulsen MG. Is routine follow-up useful after combined-modality therapy for advanced head and neck cancer? Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;125(4):379-382. doi: 10.1001/archotol.125.4.379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agrawal A, deSilva BW, Buckley BM, Schuller DE. Role of the physician versus the patient in the detection of recurrent disease following treatment for head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 2004;114(2):232-235. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200402000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agrawal A, Hammond TH, Young GS, Avon AL, Ozer E, Schuller DE. Factors affecting long-term survival in patients with recurrent head and neck cancer may help define the role of post-treatment surveillance. Laryngoscope. 2009;119(11):2135-2140. doi: 10.1002/lary.20527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flynn CJ, Khaouam N, Gardner S, et al. The value of periodic follow-up in the detection of recurrences after radical treatment in locally advanced head and neck cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2010;22(10):868-873. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2010.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kothari P, Trinidade A, Hewitt RJD, Singh A, O’Flynn P. The follow-up of patients with head and neck cancer: an analysis of 1,039 patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;268(8):1191-1200. doi: 10.1007/s00405-010-1461-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masroor F, Corpman D, Carpenter DM, Ritterman Weintraub M, Cheung KHN, Wang KH. Association of NCCN-recommended posttreatment surveillance with outcomes in patients with HPV-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(10):903-908. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.1934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corpman DW, Masroor F, Carpenter DM, Nayak S, Gurushanthaiah D, Wang KH. Posttreatment surveillance PET/CT for HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer. Head Neck. 2019;41(2):456-462. doi: 10.1002/hed.25425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imbimbo M, Alfieri S, Botta L, et al. Surveillance of patients with head and neck cancer with an intensive clinical and radiologic follow-up. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;161(4):635-642. doi: 10.1177/0194599819860808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gharzai LA, Burger N, Li P, et al. Patient burden with current surveillance paradigm and factors associated with interest in altered surveillance for early stage HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer. Oncologist. 2021;26(8):676-684. doi: 10.1002/onco.13784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beeler WH, Bellile EL, Casper KA, et al. Patient-reported financial toxicity and adverse medical consequences in head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2020;101:104521. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.104521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thorne S, Kirkham SR, MacDonald-Emes J. Interpretive description: a noncategorical qualitative alternative for developing nursing knowledge. Res Nurs Health. 1997;20(2):169-177. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1753-1760. doi: 10.1177/1049732315617444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thorne S. Data analysis in qualitative research. Evidence-Based Nursing. 2000;3(3):68-70. doi: 10.1136/ebn.3.3.68 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):37. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rai T, Clements A, Bukach C, Shine B, Austoker J, Watson E. What influences men’s decision to have a prostate-specific antigen test? a qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2007;24(4):365-371. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmm033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jensen CB, Saucke MC, Francis DO, Voils CI, Pitt SC. From overdiagnosis to overtreatment of low-risk thyroid cancer: a thematic analysis of attitudes and beliefs of endocrinologists, surgeons, and patients. Thyroid. 2020;30(5):696-703. doi: 10.1089/thy.2019.0587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang T, Mott N, Miller J, et al. Patient perspectives on treatment options for older women with hormone receptor–positive breast cancer: a qualitative study. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2017129. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.17129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macdonald C, Mazza D, Hickey M, et al. Motivators of inappropriate ovarian cancer screening: a survey of women and their clinicians. J Natl Cancer Inst Cancer Spectr. 2020;5(1):pkaa110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Hoffman JR, Kanzaria HK. Intolerance of error and culture of blame drive medical excess. BMJ. 2014;349:g5702. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heath I. Role of fear in overdiagnosis and overtreatment–an essay by Iona Heath. BMJ. 2014;349:g6123. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g6123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Redelmeier DA, Rozin P, Kahneman D. Understanding patients’ decisions: cognitive and emotional perspectives. JAMA. 1993;270(1):72-76. doi: 10.1001/jama.1993.03510010078034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bailo L, Vergani L, Pravettoni G. Patient preferences as guidance for information framing in a medical shared decision-making approach: the bridge between nudging and patient preferences. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;13:2225-2231. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S205819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brennan KE, Hall SF, Yoo J, et al. Routine follow-up care after curative treatment of head and neck cancer: a survey of patients’ needs and preferences for healthcare services. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2019;28(2):e12993. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1361-1367. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dood R, Zhou Y, Armbruster SD, et al. Defining survivorship and surveillance with evidence. JCO. 2018;36(15)(suppl):6528. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.6528 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Interview Guide