Abstract

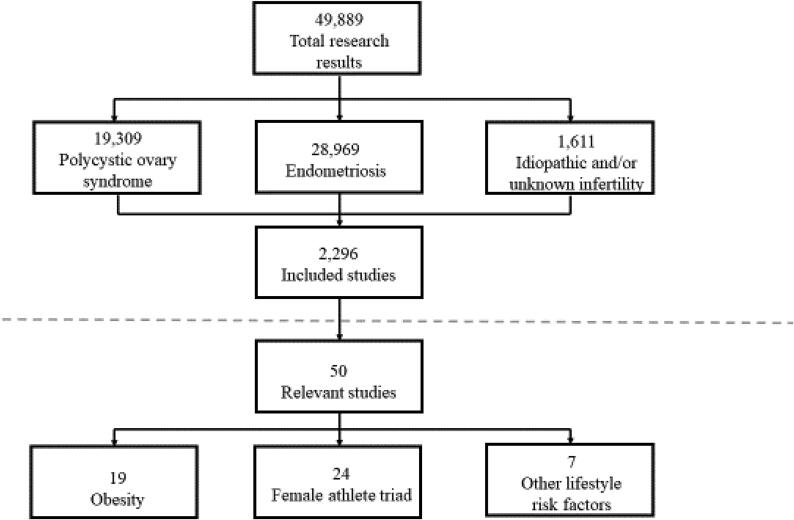

Metabolic risk factors such as obesity are considered major obstacles to female fertility. Chronic infertility imposes psychological and social burdens on women because infertility violates societal gender roles. Although the prevalence of obesity among women is expected to increase in the future, the relevance of metabolic status for fertility is still underestimated. However, the assessment of metabolic risk factors is highly relevant for understanding fertility disorders and improving infertility treatment. This narrative review discusses the associations of metabolic risk factors (e.g. obesity, female athlete triad, oxidative stress) with significant infertility. An electronic search was conducted for studies published between 2006 and 2020 in Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, ScienceDirect, PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar and related databases. In total, this search identified 19,309 results for polycystic ovary syndrome, 28,969 results for endometriosis, and only 1611 results for idiopathic and/or unknown infertility. For the present narrative review, 50 relevant studies were included: 19 studies were on obesity, 24 studies investigated the female athlete triad, and seven studies addressed other risk factors, including reactive oxygen species. This narrative review confirms the direct impact of obesity on female infertility, while the effect of other risk factors needs to be confirmed by large-scale population studies.

Keywords: Female athlete triad, Female infertility, Obesity, Oxidative stress, Polycystic ovary syndrome

Introduction

The aim of this narrative review is to offer a broad overview of the link between metabolic risk factors and fertility disorders from a female perspective. Although male-specific infertility causes more than half of all cases of involuntary childlessness (Agarwal et al., 2015), the major psychological and social burdens primarily affect women (McQuillan et al., 2003, Wright et al., 1991). The unfulfilled desire for a child and the consequences of unsuccessful attempts to conceive and deliver a child impose cultural and social burdens on women based on their internalization of cultural gender roles (Ford et al., 2002) and underlying gender beliefs. Implicit gender beliefs are learned very early in life (Devine, 1989) and, as a result, associate women with stereotypic gender roles (e.g., being responsible for care tasks and raising children) and stereotypic abilities (e.g., to conceive children). Infertility violates societal female gender role stereotypes and abilities, and if gender roles and abilities are strongly internalized, women who experience infertility are more likely to perceive themselves as defective (Greil, 1991). In order to improve women’s self-perception in the fertility process, infertility should be considered a medical condition instead. This improves women’s mental health and leads to a better understanding of gender-specific variations in the process of healthcare services (Greil et al., 2011). Assisted reproductive technology (ART) is one component of these healthcare services. Although ART is a successful means of overcoming infertility, there is still a lack of knowledge about how metabolic risk factors affect infertility, especially within the context of widespread obesity and the opposite phenomenon of the female athlete triad (eating disorder, amenorrhoea and osteoporosis). A better understanding of the impact of metabolic risk factors on infertility could inform novel or best practice treatments in ART.

The leading causes of female infertility in Western societies are ovulation disorders, tubal problems and chronic endometriosis (Abrao et al., 2013). The same major pathophysiological causes may be responsible for so-called ‘idiopathic infertility’, where the reason for infertility is unknown. The prevalence of idiopathic infertility varies between 8% and 37% in women (Ray et al., 2012). Metabolic risk factors may contribute to understanding idiopathic infertility in women and, thus, reduce the proportion of unexplained infertility in women.

The interplay of metabolic risk factors such as obesity and the female athlete triad (eating disorder, amenorrhoea and osteoporosis) with infertility outcomes is the focus of this narrative review. The aim of this review is to develop a better understanding of the relationship between female-specific causes of infertility and how they might be exacerbated by metabolic risk factors. The role of both obesity and the female athlete triad on female infertility disorders will be discussed, including the impact of oxidative stress via elevated levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) as a mediating variable. Previous studies focusing on the associations between risk factors and infertility disorders have had small sample sizes and low statistical power. Therefore, the main conclusion of this review is that further research should address this information gap with large-sample studies.

This narrative review about the female perspective of metabolic risk factors and fertility disorders is divided into three sections. First, an overview of the two major infertility disorders – polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and endometriosis – is provided to introduce the topic of major infertility disorders in women. Next, the associations between the metabolic risk factors involved in obesity and the female athlete triad with infertility are discussed based on a narrative literature review. Finally, oxidative stress as a marker for adverse lifestyle factors contributing to infertility and obesity is discussed, because this has been neglected to date in research on metabolic risk factors and infertility.

Polycystic ovary syndrome

Regulatory imbalances between reproduction and metabolism caused by disorders such as PCOS (in which symptoms are due to elevated androgen levels) often result in ovarian dysfunction, and increase the risk of cardiovascular and metabolic disorders in women (Dokras, 2013, Studen and Pfeifer, 2018, Torchen, 2017). PCOS is a complex and multi-faceted endocrine disorder in women of reproductive age, affecting approximately 2–20% (Jain et al., 2021, Pal, 2014), depending on the clinical inclusion criteria. PCOS impacts various aspects of a woman's life, such as aesthetics, reproduction, metabolism, psychological well-being and sexuality (Aversa et al., 2020). The most important risk factors for PCOS in adult women include diabetes type 1 or 2, and gestational diabetes. Insulin resistance affects 50–70% of women with PCOS (Moghetti, 2016, Sirmans and Pate, 2014) and leads to several comorbidities, including metabolic syndrome, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, glucose intolerance and diabetes (Dokras, 2013). Studies show that women with PCOS are more likely to have increased coronary artery calcium scores and increased carotid intima–media thickness, which are predictors of subclinical atherosclerosis and other cardiovascular events (Karthik et al., 2019, Sathyapalan and Atkin, 2012, Sirmans and Pate, 2014, Woodward et al., 2019). Mental health disorders, including depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, binge drinking and eating disorders, also occur more frequently in women with PCOS (Brutocao et al., 2018, Sayyah-Melli et al., 2015, Scaruffi et al., 2014).

Medication alone is ineffective at treating PCOS. Only therapy that includes significant lifestyle changes such as weight loss and physical exercise combined with treatment with metformin and anti-androgen medication can alleviate PCOS symptoms (Kim et al., 2020).

Endometriosis

Another disorder that has a negative effect on reproduction is endometriosis, a condition in which specific tissue adhesions are formed outside the uterus, often on the ovaries and fallopian tubes. The prevalence of endometriosis reported in general population studies ranged from approximately 1% to 10%, usually late in the reproductive period but before menopause, between the ages of 35 and 50 years (As-Sanie et al., 2019, Ghiasi et al., 2020, Morassutto et al., 2016). Some studies found an inverse relationship between body mass index (BMI)1 and endometriosis (Liu and Zhang, 2017), and a reduced frequency of stage 1 endometriosis in obese women (Holdsworth-Carson et al., 2018). Hence, obese women had lower relative risk for endometriosis compared with women of normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) (Liu and Zhang, 2017). On the other hand, opposite findings also suggest mixed results (Peterson et al., 2013). As such, the role of BMI in the cause or effect of endometriosis remains unclear. However, BMI can be used for subclassifying endometriosis.

Women with a genetic predisposition for endometriosis are more likely to be affected by endometriosis, low progesterone levels and hormonal imbalances. Furthermore, endometriosis is potentially caused by a subset of target genes (Rahmioglu et al., 2014).

A study by Sapkota et al. (2017) identified approximately 14 genomic regions with 19 independent single nucleotide polymorphisms that might explain approximately 5% of the variance in endometriosis. These specific genes also play important roles in female sex steroid hormone signalling and functions.

There is also a genetic component to the development of endometriosis (Fung et al., 2017, Fung and Montgomery, 2018, Gajbhiye et al., 2018, Krishnamoorthy and Decherney, 2017). Oestrogens have different functional effects on metabolism in women, including regulation of the visceral distribution of fat mass, pro-lipolytic (ability to break up fat) activities and antilipogenic (ability to degrade fat) activities in adipocytes, and pancreatic β-cell activity, which is involved in the development of insulin resistance (Fontana and Della Torre, 2016).

Search strategy for the narrative review

In contrast to original research articles, literature reviews – such as this review – do not present new findings based on data but intend to evaluate what is published in primary research with respect to a certain topic (Ferrari, 2015). Thus, the main purpose of this literature review is to gain a wider view of how a metabolic risk factor affects female fertility. The literature search performed for this review was based on the lines of searches for narrative reviews (selective focus) and features of the methodology of systematic reviews (to present criteria for selecting articles from the literature). The literature search was based on the five largest electronic databases with respect to medical research areas: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, ScienceDirect, PubMed, Scopus and Google Scholar. The selection of articles was based on the search terms ‘idiopathic and/or unknown infertility’, ‘metabolic risk factors’, ‘obesity’, ‘female athlete triad’, ‘endometriosis’, ‘polycystic ovarian syndrome’ and ‘reactive oxidant species’ alone and in different combinations. The identified articles were read and assessed for relevance. The inclusion criteria were: (i) publication in English in a peer-reviewed academic journal between 2006 and 2020; (ii) research focusing on metabolic risk factors and female idiopathic infertility; and (iii) accessible abstracts and full text. The exclusion criteria were: (i) editorials, commentaries, discussion papers, conference abstracts and duplicates; (ii) topics in journals focusing solely on healthcare professionals and caregivers; and (iii) clinical trials of pharmaceutical treatments.

The literature search identified 19,309 results for PCOS, 28,012 results for endometriosis, and only 1611 results for idiopathic and/or unknown infertility. An association between obesity and female infertility was reported in 1880 studies. Only 416 studies that investigated female athlete triad and female infertility were found. After screening the articles, 50 relevant studies were included in the review (Fig. 1). The screening criterion was studies considering statistical association measures, which were only available for the variable ‘obesity’. In addition, studies focusing on the pathophysiological pathway between the female athlete triad and lifestyle factors in female infertility were included in this review. Hence, the authors could not identify studies referring to statistical association measures for the female athlete triad and lifestyle factors in the context of female infertility. Research considering results from animal models was excluded. Nineteen studies focused on obesity, 24 studies addressed the female athlete triad, and seven studies investigated other lifestyle-associated risk factors for infertility, such as ROS.

Fig. 1.

Selection criteria for studies included.

Obesity and infertility

Several studies have shown that obesity interferes with fertility. Obese women have a three-fold higher risk of infertility than non-obese women (Wise et al., 2010). Some obese women can conceive after seeking medical help (Vahratian and Smith, 2009). The fertility of obese women seems to be impaired in both natural and assisted conception cycles (Silvestris et al., 2018). It has been shown that the probability of pregnancy is reduced by 5% per unit of BMI exceeding 29 kg/m2 (Jungheim and Moley, 2010).

Obesity in women can be considered a significant risk factor for the absence of ovulation [relative risk 2.7; 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.0–3.7] and can lead to permanent female infertility (Pandey et al., 2010). More than 20% of American women of reproductive age are obese (Broughton and Moley, 2017). Finkelstein et al. predicted that if the anticipated 33% increase in obesity and 130% increase in severe obesity over the next two decades occur, there will be an increase in the debate over the relevance of obesity as a risk factor for infertility (Finkelstein et al., 2012). High BMI in females is associated with an increase in serum leptin and follicular fluid leptin levels, both known as satiety hormones that regulate energy balance by inhibiting hunger. It is also associated with lower levels of serum adiponectin, which regulates glucose levels and fatty acid breakdown. Elevated serum leptin levels directly affect the response of receptors on theca and granulosa cells (including somatic cells of the sex cord that affect the developing female gamete), followed by a decrease in the reactive process of ovarian steroid genesis (Pandey et al., 2010).

Low serum adiponectin levels and elevated circulating insulin levels potentially induce hyperandrogenaemia, resulting in a higher risk for menstrual irregularity, hirsutism, acne and PCOS, and inhibiting the expression of hepatic sex hormone-binding globulin. Obesity is also present in 20–70% of women with PCOS, depending on geographic region (Li et al., 2018, Lim et al., 2012, Pandey et al., 2010, Silvestris et al., 2018). Obese women exhibit reduced fecundity, even after several ART treatment cycles (Khairy and Rajkhowa, 2017, MacKenna et al., 2017).

Obesity results in exposure to excess free fatty acids, which pathologically affect reproductive processing by inducing cellular damage and a chronic, low-grade inflammatory condition (Broughton and Moley, 2017). The endometrium in obese women tends to have decreased stromal decidualization (low capacity for fertilization), which causes subfecundity with impaired receptivity and higher rates of pre-eclampsia, miscarriage and stillbirth (Catalano and Shankar, 2017).

Additionally, ovarian disorders may be strongly associated with body fat mass. A recent study by Chitme et al. (2017) showed significantly higher total body fat distribution (including trunk, arm and leg subcutaneous fat) in patients with PCOS than in the healthy control group. Mean BMI, waist circumference and hip circumference of the individuals with PCOS were 28.2 ± 6.08 kg/m2 (24.12 ± 4.69 kg/m2 for the control group), 97.44 ± 15.11 cm (84.83 ± 19.23 cm for the control group) and 109.22 ± 17.39 cm (99.02 ± 14.97 cm for the control group), respectively (Chitme et al., 2017).

Other health risks in patients with PCOS include hypertension, with clinically relevant elevations of systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure (Amiri et al., 2020). Chronic hypertension is a leading cause of premature death in many Western countries.

The adverse effects of obesity and high body fat mass on infertility have been supported by a few studies of preventative interventions, including appropriate nutrition, weight loss, physical activity and bariatric surgery (Butterworth et al., 2016, Mitchell and Fantasia, 2016).

There is a strong link between high BMI and ART outcomes. A systematic overview of the correlation between increased BMI and ART outcomes was provided by Supramaniam et al. (2018). They found a significantly lower clinical pregnancy rate among women with BMI between 25 and 29.9 kg/m2 than among women with normal BMI (<25 kg/m2) [19 studies pooled, odds ratio (OR) 0.89, 95% CI 0.84–0.94, P < 0.00001]. Women with BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 had a significantly lower clinical pregnancy rate compared with women with BMI < 25 kg/m2 (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.74–0.87, P < 0.00001). Moreover, high BMI in women is also correlated with an elevated rate of miscarriage. Women with BMI between 25 and 29.9 kg/m2 were more likely to have a miscarriage than women with BMI < 25 kg/m2 (18 studies pooled, OR 1.15 95% CI 1.05–1.26, P = 0.002). Furthermore, the risk of miscarriage was higher in women with BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 than in women with BMI < 25 kg/m2 (17 studies pooled, OR 1.52, 95% CI 1.28–1.81, P < 0.00001). These outcomes justify a critical consideration of the success of ART among women with the metabolic risk factor of being overweight.

Female athlete triad and infertility

The female athlete triad involves being underweight (often associated with an eating disorder), having a low calorie intake, and engaging in excessive physical activity (Gudmundsdottir et al., 2009). The latter is widespread in professional female athletes combined with being underweight (Nazem and Ackermann, 2012, Weiss Kelly and Hecht, 2016). The female athlete triad leads to menstrual dysfunction, low energy availability and decreased bone mineral density (Curry et al., 2015, Holtzman et al., 2019, Nazem and Ackermann, 2012, Stickler et al., 2015).

The risk of infertility is accompanied by menstrual dysfunction in individuals with the female athlete triad. The causes of menstrual dysfunction are various. Amenorrhoea is a typical physical symptom in young women, defined as intermittent menses at intervals of 3 months or longer. Amenorrhoea is further defined as an absence of menses by the age of 15 years, despite normal secondary sexual development, or no menses within 5 years after breast development if that occurred before 10 years of age (Curry et al., 2015, Nazem and Ackermann, 2012). Anorexia nervosa is often responsible for a delay in the age of menarche (Hoffman et al., 2011, Howard, 2018). A chronic negative energy balance and prolonged physical exertion with no compensatory increased energy intake often result in amenorrhoea (Allaway et al., 2016).

The menstrual cycle in female athletes can return after a disturbance period of low calorie intake, even when low energy balance persists and body weight and fat mass composition have not changed. Eating disorders also have negative effects on the central nervous system and are associated with a higher risk of mortality. Chronic undernutrition or wasting leads to decreased activity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis, which is responsible for the synthesis of sex hormones. Inhibition of the expression of gonadotropin-releasing hormone leads to reduced levels of follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone, causing adverse physiological interactions during gonadal steroid synthesis, gonadotropin secretion and follicle development (Fontana and Della Torre, 2016).

Hepatic oestrogen receptor alpha (ERα) plays a specific role as an important mediator of the relationship between undernutrition or wasting and infertility (Archer et al., 2016). Low calorie intake over a long time decreases hepatic ERα activity and impairs oestrogen synthesis (Della Torre et al., 2014, Fontana and Della Torre, 2016). Liver ERα is responsible for the disposal of cholesterol that circulates during all phases of the reproductive cycle.

Compared with the metabolic risk factors of obesity, correlations of the female athlete triad with infertility outcomes and successful ART have not been investigated in large interventional studies. A recent study by Boutari et al. (2020) summarized pooled findings from 24 clinical studies concerning reproductive outcomes and being underweight. The included studies had small sample sizes and mainly focused on the pathological pathway between underweight, as one characteristic of the female athlete triad, and infertility. Whether there is significant correlation between the female athlete triad and infertility is still unknown, based on the findings of this literature review.

Oxidative stress and infertility

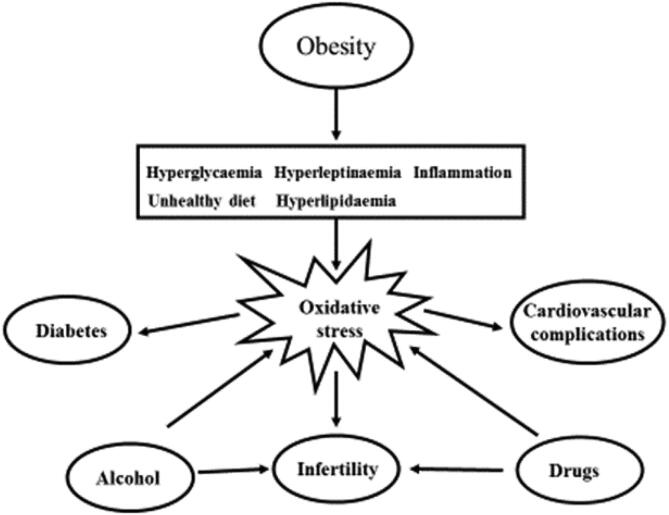

In addition to a genetic predisposition to infertility, exposure to environmental toxins, chronic inflammation and ROS, as pro-inflammatory mediators, also play roles in the process of infertility; however, the potential mechanisms of action are not clearly understood. Oxidative stress is an imbalance between pro-oxidants and antioxidants that induces several reproductive disorders, such as PCOS and endometriosis, and which may contribute to explaining idiopathic infertility. Studies have shown (Fig. 2) that the link between body weight and lifestyle factors, including cigarette smoking, alcohol abuse and drug consumption, can induce the production of free radicals, which often results in infertility (Agarwal et al., 2012, Gupta et al., 2014, Lu et al., 2018, Manna and Jain, 2015, Rehman et al., 2018, Roussou et al., 2013, Ruder et al., 2008). For example, exposure to toxic chemicals and pro-oxidants in cigarette smoke stimulates ROS production. Inhalation of tobacco smoke leads to two independent biochemical processes: first, in the tar phase, stable free radicals are generated; and second, in the gas phase, toxins and free radicals are released. ROS, such as H2O2, hydroxyl radicals and sulphur monoxide anions, are produced by burning cigarettes, and they are toxic degradation products that fundamentally damage DNA and germ cells. Even passive exposure to cigarette smoke is closely associated with lower conception capability and preterm delivery. Several studies have identified the effects of cigarette and tobacco smoke on fetuses and embryos. In fact, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), followed by decreased oxygen supply to the fetus and poor maternal nutrition, have been linked to ROS (Agarwal et al., 2012).

Fig. 2.

Conditions generating oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of obesity (adapted from Manna and Jain, 2015).

Moderate alcohol consumption may also result in IUGR, low birth weight and a higher proportion of congenital fetal anomalies (Henderson et al., 2007, Lundsberg et al., 2015). Preterm delivery and, more commonly, spontaneous abortion and pregnancy loss within the early months of pregnancy often occur in women who abuse alcohol (Bailey and Sokol, 2011, Mamluk et al., 2017). The oxidative process of ethanol elimination evokes oxidative stress and is responsible for ROS activation.

In addition to alcohol abuse, the intake of cannabinoids, cocaine and other psychedelic drugs can induce ROS activation (Rajesh et al., 2010). Cannabinoids affect terminal conditions in the peripheral and central nervous systems. The psychological addiction to marijuana is attributed to the presence of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, also known as ‘THC’. Endocannabinoid receptors located in the mammalian brain may affect female reproductive organs, including the uterus and ovary (Brents, 2016, du Plessis et al., 2015). Therefore, cannabinoid agonists may interrupt the normal reproductive state by promoting the production of free radicals. Beyond psychological addiction, other adverse health effects, including low birth weight, prematurity, IUGR and miscarriage, can occur due to use of cocaine (Cain et al., 2013). The oxidative pathway activated by cocaine intoxication and the corresponding formaldehyde metabolites may be responsible for permanent ROS activation (Agarwal et al., 2012).

Summary

New research perspectives on metabolic and lifestyle-related risk factors for infertility in women are discussed in this narrative review. In summary of the results of the reviewed studies, it is hypothesized that metabolic risk factors are comorbidities of infertility and could also be seen as markers for infertility. For example, women who have PCOS are more likely to be overweight. Being overweight has an unfavourable influence on hormonal balance, which is essential for reproductive success. A reduction in body weight usually accompanies an improvement in hormone balance in women, and increases the likelihood of conception. Thus, obesity as a comorbidity of PCOS must be considered when treating infertile women with PCOS to increase their reproductive success. Metabolic risk factors may also cause infertility, and work as confounders of infertility. However, the current state of the studies does not allow this conclusion to be drawn; this requires further investigation.

The major challenge that needs to be addressed in future research is the application of sophisticated methods to determine the impact of these risk factors on infertility in population-based studies. Better knowledge of the pathways linking metabolism and physical activity with infertility is needed to inform novel or best practice treatments in ART. However, before administering ART to females, it is crucial to assess obesity, and perhaps also the female athlete triad, to ensure the highest pregnancy and baby take-home rates to reduce financial costs and patient stress.

Nevertheless, the unfulfilled desire for a child is also a social phenomenon beyond the biomedical perspective. Consequently, interdisciplinary cooperation between the biomedical and social sciences is needed to close the information gap between robust molecular biomarkers and social predictors of infertility. The first step must be the systematic establishment of a consensus definition of infertility, which does not yet exist. In females, PCOS is a major, chronic hormonal imbalance associated with higher risks of diabetes mellitus type 2, hypertension and dyslipidaemia. In contrast, the female athlete triad combined with chronic low calorie intake over a long time decreases the expression of hepatic ERα, which impacts the clearance of cholesterol. Based on this narrative literature review, it can be concluded that the risk factors for female infertility are commonly associated with lifestyle and unfavourable health behaviours that promote ROS activation. ROS have a negative impact on female fertility and increase the risk of PCOS and endometriosis. Thus, there is a need for further research into metabolic risk factors for female infertility. Better diagnostic capabilities can reduce the proportion of infertility causes that are clinically considered as idiopathic.

Although the negative impacts of ROS on women’s reproductive function have been identified, the complete pathways, including molecular infertility markers identified by new '-omics' fields (genomics, proteomics, transcriptomics and metabolomics), have to be studied in more detail. This is essentially to better understand the link between metabolic status and fertility. The assessment of molecular infertility markers can be facilitated by applying new methods of extracting tissue and blood in large-scale population-based studies. Large-scale population-based studies using various biobanks – such as the UK Biobank and the German National Cohort (Trehearne, 2016, German National Cohort (GNC) Consortium, 2014) – can help to improve our knowledge on the link between metabolic risk factors and infertility in the future. As the prevalence of obesity among women is expected to increase in the next two decades (Finkelstein et al., 2012), it is crucial to understand the relevance of metabolic status for fertility in more detail.

Declaration

The author reports no financial or commercial conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable and helpful comments.

Dr Westerman is funded by the Mortality Follow-up of the German National Cohort, Federal Ministry of Education and Research of Germany (Grant No. 01ER1801D).

Biography

Ronny Westerman is a researcher at the Competence Centre of Mortality Follow-up of the German National Cohort Consortium at the Federal Institute for Population Research, Wiesbaden (Germany) and a collaborator of the Global Burden of Disease Study at the University of Washington (USA). His current research interests are in demography, epidemiology and fertility disorders.

Footnotes

According to the World Health Organization, BMI can be categorized as underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2) and obese (≥30 kg/m2). However, individual variations do exist, and an increased BMI does not necessarily correlate with the individual's health status. According to Nuttall (2015), BMI is a rather poor indicator of percentage and/or distribution of body fat, directly linked to the individual's health status. Thus, the use of phrases such as ‘normal weight’ can be misleading.

References

- Abrao M.S., Muzii L., Marana R. Anatomical causes of female infertility and their management. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2013;123(2):18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal A., Aponte-Mellado A., Premkumar B.J., Shaman A., Gupta S. The effects of oxidative stress on female reproduction: a review. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2012;10:49. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-10-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal A., Mulgund A., Hamada A., Chyatte M.R. A unique view on male infertility around the globe. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2015;13:37. doi: 10.1186/s12958-015-0032-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allaway H.C.M., Southmayd E.A., De Souza M.J. The physiology of functional hypothalamic amenorrhea associated with energy deficiency in exercising women and in women with anorexia vervosa. Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Invest. 2016;25(2):91–119. doi: 10.1515/hmbci-2015-0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amiri M., Tehrani F.R., Behboudi-Gandevani S.M., Bidhendi-Yarandi R.M., Carmina E. Risk of hypertension in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2020;18(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s12958-020-00576-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer A.E., Rogers R.S., Wheatley J.L., White K., Rumi M.A.K., Soares M.J., Geiger P.C. Regulation of metabolism by estrogen receptor alpha. FASEB J. 2016;30(1) doi: 10.1096/fasebj.30.1_supplement.1008.7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- As-Sanie S., Black R., Giudice L.C., Gray Valbrun T., Gupta J., Jones B., Laufer M.R., Milspaw A.T., Missmer S.A., Norman A., Taylor R.N., Wallace K., Williams Z., Yong P.J., Nebel R.A. Assessing research gaps and unmet needs in endometriosis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019;221(2):86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aversa A., La Vignera S., Rago R., Gambineri A., Nappi R.E., Calogero A.E., Ferlin A. Fundamental concepts and novel aspects of polycystic ovarian syndrome: expert consensus resolutions. Front. Endocrinol. 2020;516(11) doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.00516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey B.A., Sokol R.J. Preterm delivery, spontaneous abortion and pregnancy loss and alcohol abuse. Alcohol. Res. Health. 2011;34(1):86–91. PMID: 23580045. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutari C., Pappas P.D., Mintziori G., Nigdelis M.P., Athanasiadis L., Goulis D.G., Mantzoros C.S. The effect of underweight on female and male reproduction. Metabolism. 2020;107:154229. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brents L.K. Marijuana, the endocannabinoid system and the female reproductive system. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2016;89(2):175–191. PMID: 27354844. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brutocao C., Zaiem F., Alsawas M., Morrow A.S., Murad M.H., Javed A. Psychiatric disorders in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocrine. 2018;62(2):318–325. doi: 10.1007/s12020-018-1692-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton D.E., Moley K.H. Obesity and female infertility: potential mediators of obesity's impact. Fertil. Steril. 2017;107(4):840–847. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth J., Deguara J., Borg C.-M. Bariatric surgery, polycystic ovary syndrome, and infertility. J. Obes. 2016;2016:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2016/1871594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain M.A., Bornick P., Whiteman V. The maternal, fetal, and neonatal effects of cocaine exposure in pregnancy. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;56(1):124–132. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31827ae167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano P.M., Shankar K. Obesity and pregnancy: mechanisms of short term and long term adverse consequences for mother and child. BMJ. 2017;8(356) doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitme H.R., Al Azawi E.A.K., Al Abri A.M., Al Busaidi B.M., Salam Z.K.A., Al Taie M.M., Al Harbo S.K. Anthropometric and body composition analysis of infertile women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2017;12(2):139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jtumed.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry E.J., Logan C., Ackerman K., McInnis K.C., Matzkin E.G. Female athlete triad awareness among multispecialty physicians. Sports Med. Open. 2015;1(38) doi: 10.1186/s40798-015-0037-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della Torre S., Benedusi V., Fontana R., Maggi A. Energy metabolism and fertility: A balance preserved for female health. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2014;10(1):13–23. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine P.G. Stereotypes and prejudice: Their automatic and controlled components. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989;56(1):5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dokras A. Cardiovascular disease risk in women with PCOS. Steroids. 2013;78(8):773–776. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- du Plessis S.S., Agarwal A., Syriac A. Marijuana, phytocannabinoids, the endocannabinoid system, and male fertility. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2015;32(11):1575–1588. doi: 10.1007/s10815-015-0553-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari R. Writing narrative style literature reviews. Med. Writ. 2015;2015(24):230–235. doi: 10.1179/2047480615Z.000000000329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein E.A., Khavjou O.A., Thompson H., Trogdon J.G., Pan L., Sherry B., Dietz W. Obesity and severe obesity forecasts through 2030. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012;42(6):563–570. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana R., Della Torre S. The deep correlation between energy metabolism and reproduction: a view on the effects of nutrition for women fertility. Nutrients. 2016;8(2):87. doi: 10.3390/nu8020087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford T.E., Stevenson P.R., Wienir P.L., Wait R.F. The role of internalization of gender norms in regulating self-evaluations in response to anticipated delinquency. Soc. Psyc. Qua. 2002;65(2):202–2012. doi: 10.2307/3090101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fung J.N., Sapkota Y., Nyholt D.R., Montgomery G.W. Genetic risk factors for endometriosis. J. Endometr. Pelvic Pain Disord. 2017;9(2):69–76. doi: 10.5301/je.5000273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fung J.N., Montgomery G.W. Genetics of Endometriosis: State of the art on genetic risk factors for endometriosis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018;50:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajbhiye R., Fung J.N., Montgomery G.W. Complex genetics of female fertility. NPJ Genom. Med. 2018;3(29) doi: 10.1038/s41525-018-0068-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German National Cohort (GNC) Consortium The German National Cohort: aims, study design and organization. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2014;29(5):371–382. doi: 10.1007/s10654-014-9890-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiasi M., Kulkarni M.T., Missmer S.A. Is endometriosis more common and more severe than it was 30 years ago? J. Minimally Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27(2):452–461. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2019.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greil A., McQuillan J., Slauson-Belvis K. The social construction of infertility. Soc. Com. 2011;5(8):736–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2011.00397.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greil A.L. A secret stigma: The analogy between infertility and chronic illness and disability. Adv. Med. Sociol. 1991;2(1):17–38. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S., Ghulmiyyah J., Sharma R., Halabi J., Agarwal A. Power of proteomics in linking oxidative stress and female infertility. Biomed Res. Int. 2014;2014:1–26. doi: 10.1155/2014/916212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudmundsdottir S.L., Flanders W.D., Augestad L.B. Physical activity and fertility in women: the North-Trøndelag Health Study. Hum. Reprod. 2009;24(12):3196–3204. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson J., Kesmodel U., Gray R. Systematic review of the fetal effects of prenatal binge drinking. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2007;61(12):1069–1073. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.054213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman E.R., Zerwas S.C., Bulik C.M. Reproductive issues in anorexia nervosa. Expert Rev. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;6(4):403–414. doi: 10.1586/eog.11.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdsworth-Carson S.J., Dior U.P., Colgrave E.M., Healey M., Montgomery G.W., Rogers P.AW., Girling J.E. The association of body mass index with endometriosis and disease severity in women with pain. J. Endometr. Pelvic Pain Disord. 2018;10(2):79–87. doi: 10.1177/2284026518773939. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman B., Tenforde A.S., Parziale A.L., Ackerman K.E. Characterization of risk quantification differences using female athlete triad cumulative risk assessment and relative energy deficiency in sport clinical assessment tool. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2019;12:1–7. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.2019-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard S.R. The genetic basis of delayed puberty. Front. Endocrinol. 2018;10:423. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain T., Negris O., Brown D., Galic I., Salimgaraev R., Zhaunova L. Characterization of polycystic ovary syndrome among Flo app users around the world. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2021;19(2021):36. doi: 10.1186/s12958-021-00719-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungheim E.S., Moley K.H. Current knowledge of obesity's effects in the pre- and periconceptional periods and avenues for future research. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;203(6):525–530. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karthik S., Vipin V.P., Kapoor A., Tripathi A., Shukla M., Dabadghao P. Cardiovascular disease risk in the siblings of women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum. Reprod. 2019;34(8):1559–1566. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dez104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khairy M., Rajkhowa M. Effect of obesity on assisted reproductive treatment outcomes and its management: a literature review. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2017;19(1):47–54. doi: 10.1111/tog.12343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C.H., Chon S.J., Lee S.H. Effects of lifestyle modification in polycystic ovary syndrome compared to metformin only or metformin addition: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(7802) doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-64776-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamoorthy K., Decherney A.H. Genetics of endometriosis. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017;60(3):531–538. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Lin H., Ping P., Yang D., Zhang Q. Impact of central obesity on women with polycystic ovary syndrome undergoing in vitro fertilization. Biores. Open Access. 2018;7(1):116–122. doi: 10.1089/biores.2017.0040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S.S., Davies M.J., Norman R.J., Moran L.J. Overweight, obesity and central obesity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2012;18(6):618–637. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dms030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Zhang W. Association between body mass index and endometriosis risk: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(29):46928–46936. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J., Wang Z., Cao J., Chen Y., Dong Y. A novel and compact review on the role of oxidative stress in female reproduction. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2018;16(1):80. doi: 10.1186/s12958-018-0391-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundsberg L.S., Illuzzi J.L., Belanger K., Triche E.W., Bracken M.B. Low-to-moderate prenatal alcohol consumption and the risk of selected birth outcomes: a prospective cohort study. Ann. Epidemiol. 2015;25(1):46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenna A., Schwarze J.E., Crosby J.A., Zegers-Hochschild F. Outcome of assisted reproductive technology in overweight and obese women. JBRA Assist Reprod. 2017;21(2):79–83. doi: 10.5935/1518-0557.20170020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna P., Jain S.K. Obesity, oxidative stress, adipose tissue dysfunction, and the associated health risks: causes and therapeutic strategies. Metabolic Syndrome Related Disord. 2015;13(15):423–444. doi: 10.1089/met.2015.0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamluk L., Edwards H.B., Savović J., Leach V., Jones T., Moore T.H.M., Ijaz S., Lewis S.J., Donovan J.L., Lawlor D., Smith G.D., Fraser A., Zuccolo L. Low alcohol consumption and pregnancy and childhood outcomes: time to change guidelines indicating apparently 'safe' levels of alcohol during pregnancy? A systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ Open. 2017;3(7):e015410. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuillan J., Greil A.L., White L.K., Jacob J.M. Frustrated fertility: infertility and psychological distress among women. J. Marriage Fam. 2003;65(4):1007–1018. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.01007.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell A., Fantasia H.C. Understanding the effect of obesity on fertility among reproductive-age women. Nurs. Womens Health. 2016;20(4):368–376. doi: 10.1016/j.nwh.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghetti P. Insulin resistance and polycystic ovary syndrome. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2016;22(36):5526–5534. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666160720155855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morassutto C., Monasta L., Ricci G., Barbone F., Ronfani L., Shen R. Incidence and estimated prevalence of endometriosis and adenomyosis in Northeast Italy: a data linkage study. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(4):e0154227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazem T.G., Ackermann K.E. The female athlete triad. Sports Health. 2012;4(4):302–311. doi: 10.1177/1941738112439685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuttall F.Q. Body mass index, obesity, BMI, and health. A critical review. Nutrit. Today. 2015;50(3):7–128. doi: 10.1097/NT.0000000000000092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey S.H., Pandey S., Maheshwari A., Bhattacharya S. The impact of female obesity on the outcome of fertility treatment. J. Hum. Reprod. Sci. 2010;3(2):62–67. doi: 10.4103/0974-1208.69332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal L. first ed. Springer; New York, NY: 2014. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Current and Emerging Concepts. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C.M., Johnstone E.B., Hammoud A.O., Stanford J.B., Varner M.W., Kennedy A., Chen Z., Sun L., Fujimoto V.Y., Hediger M.L., Buck Louis G.M. ENDO Study Working Group Risk factors associated with endometriosis: importance of study population for characterizing disease in the ENDO Study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;208(6):451.e1–451.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahmioglu N., Nyholt D.R., Morris A.P., Missmer S.A., Montgomery G.W., Zondervan K.T. Genetic variants underlying risk of endometriosis: insights from meta-analysis of eight genome-wide association and replication datasets. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2014;20(5):702–716. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmu015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajesh M., Mukhopadhyay P., Haskó G., Liaudet L., Mackie K., Pacher P. Cannabinoid-1 receptor activation induces reactive oxygen species-dependent and -independent mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and cell death in human coronary artery endothelial cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010;160(3):688–700. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00712.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray A., Shah A., Gudi A., Homburg R. Unexplained infertility: an update and review of practice. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 2012;24(6):591–602. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2012.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehman R., Abidi S.H., Alam F. Metformin, oxidative stress, and infertility: a way forward. Front. Physiol. 2018;9(1722) doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussou P., Tsagarakis N.J., Kountouras D., Livadas S., Diamanti-Kandarakis E. Beta-Thalassemia major and female fertility: the role of iron and iron-induced oxidative stress. Anemia. 2013;2013:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2013/617204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruder E.H., Hartmann T.J., Blumberg J., Goldman M.B. Oxidative stress and antioxidants: exposure and impact on female fertility. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2008;14(4):345–357. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmn011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapkota Y., Steinthorsdottir V., Morris A.P., Fassbender A., Rahmioglu N., De Vivo I., Buring J.E., Zhang F., Edwards T.L., Jones S., O D., Peterse D., Rexrode K.M., Ridker P.M., Schork A.J., MacGregor S., Martin N.G., Becker C.M., Adachi S., Yoshihara K., Enomoto T., Takahashi A., Kamatani Y., Matsuda K., Kubo M., Thorleifsson G., Geirsson R.T., Thorsteinsdottir U., Wallace L.M., Yang J., Velez Edwards D.R., Nyegaard M., Low S.-K., Zondervan K.T., Missmer S.A., D'Hooghe T., Montgomery G.W., Chasman D.I., Stefansson K., Tung J.Y., Nyholt D.R. Meta-analysis identifies five novel loci associated with endometriosis highlighting key genes involved in hormone metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2017;8(1) doi: 10.1038/ncomms15539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sathyapalan T., Atkin S.L. Recent advances in cardiovascular aspects of polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2012;166(4):575–583. doi: 10.1530/EJE-11-0755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayyah-Melli M., Alizadeh M., Pourafkary N., Ouladsahebmadarek E., Jafari-Shobeiri M., Abbassi J., Kazemi-Shishvan M.A., Sedaghat K. Psychosocial factors associated with polycystic ovary syndrome: a case control study. J. Caring Sci. 2015;4(3):225–231. doi: 10.15171/jcs.2015.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaruffi E., Gambineri A., Cattaneo S., Turra J., Vettor R., Mioni R. Personality and psychiatric disorders in women affected by polycystic ovary syndrome. Front. Endocrinol. 2014;5(185) doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirmans S.M., Pate K.A. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014;2014(6):1–13. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S37559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvestris E., de Pergola G., Rosania R., Loverro G. Obesity as disruptor of the female fertility. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2018;16(1):22. doi: 10.1186/s12958-018-0336-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickler L., Hoogenboom B.J., Smith L. The female athlete triad-what every physical therapist should know. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2015;10(4):563–571. PMCID: PMC4527203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studen K.L., Pfeifer M. Cardiometabolic risk in polycystic ovary syndrome. Endocr. Con. 2018;7(7):R238–R251. doi: 10.1530/EC-18-0129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supramaniam P.R., Mittal M., McVeigh E., Lim L.N. The correlation between raised body mass index and assisted reproductive treatment outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the evidence. Reprod. Health. 2018;15:34. doi: 10.1186/s12978-018-0481-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torchen L.C. Cardiometabolic Risk in PCOS: More than a reproductive disorder. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2017;17(12):137. doi: 10.1007/s11892-017-0956-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trehearne A. Genetics, lifestyle and environment. UK Biobank is an open access resource following the lives of 500,000 participants to improve the health of future generations. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2016;59(3):361–367. doi: 10.1007/s00103-015-2297-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahratian A., Smith Y.R. Should access to fertility-related services be conditional on body mass index? Hum. Reprod. 2009;24(7):1532–1537. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss Kelly A.K., Hecht S., Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness The Female Athlete Triad. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2) doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise L.A., Rothman K.J., Mikkelsen E.M., Sorensen H.T., Riis A., Hatch E.E. An internet-based prospective study of body size and time-to-pregnancy. Hum. Reprod. 2010;25(1):253–264. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward A., Klonizakis M., Lahart I., Carter A., Dalton C., Metwally M., Broom D. The effects of physical exercise on cardiometabolic outcomes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome not taking the oral contraceptive pill: protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2019;8(1):116. doi: 10.1007/s40200-019-00425-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright J., Duchesne C., Sabourin S., Bissonnette F., Benoit J., Girard Y. Psychosocial distress and infertility: men and women respond differently. Fertil. Steril. 1991;55(1):100–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]