Highlights

-

•

The secondary structure of casein changed in the presence of α-TOC.

-

•

After ultrasonic treatment, the PDI of α-TOC/CN nanoparticles decreased.

-

•

Fluorescence intensity of casein decreased as α-TOC concentration increased.

-

•

Ratio of α-helix to β-sheet structure in casein decreased after ultrasonic treatment.

-

•

Antioxidant activity of nanoparticles was stronger than those of the two free samples.

Keywords: α-tocopherol, Casein, Nanoparticles, Stability, Antioxidant, Ultrasound

Abstract

In this work casein (CN) was used as a carrier system for the hydrophobic agent α-tocopherol (α-TOC), and an amphiphilic self-assembling micellar nanostructure was formed with ultrasound treatment. The interaction mechanism was detected with UV–Vis spectroscopy, fluorescence spectroscopy, proton spectra, and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). The stability of the nanoparticles was investigated by using typical processing and storage conditions (thermal, photo, 20 ± 2 °C and 4 ± 2 °C). Oil-in-water emulsions containing the self-assembled nanoparticles and grape seed oil were prepared, and the effect of emulsion oxidation stability was studied using the accelerated Rancimat method. The results indicated that the UV–Vis spectra of α-TOC/CN nanoparticles complexes were different for ultrasonic treatments performed with different combinations of power (100, 200, 300 W) and time (5, 10, and 15 min). The results of UV–Vis fluorescence spectrum data indicated that the secondary structure of casein changed in the presence of α-TOC. The nanoparticles exhibited the chemical shifts of conjugated double bonds. Interactions between α-TOC and casein at different molar concentrations resulted in a quenching of the intrinsic fluorescence at 280 nm and 295 nm. Moreover, by performing FTIR deconvolution analysis and multicomponent peak modeling, the relative quantitative amounts of α-helix and β-sheet protein secondary structures were determined. The self-assembled nanoparticles can improve the stability of α-TOC by protecting them against degradation caused by light and oxygen. The antioxidant activity of the nanoparticles was stronger than those of the two free samples. Lipid hydroperoxides remained at a low level throughout the course of the study in emulsions containing 200 mg α-TOC/kg oil with the nanoparticles. The presence of 100 and 200 mg α-TOC/kg oil led to a 78.54 and 63.54 μmol/L inhibition of TBARS formation with the nanoparticles, respectively, vs the free samples containing control after 180 mins.

1. Introduction

Vitamin E is a fat-soluble vitamin composed of eight different forms of tocopherols (α, β, γ, and δ) and tocotrienols (α, β, γ, and δ) [19]. Vitamin E compounds are known to inhibit lipid oxidation in foods, and the most biologically active of these compounds is α-TOC [31], [33]. Therefore, it has been used as a food additive [6]. α-TOC is known to protect polyunsaturated lipids by binding and trapping free radicals and by quenching singlet molecular oxygen [24].

The lipophilic compound α-TOC is poorly soluble in water and biologically unstable against factors such as light and oxygen. This limits its storage and applications in the pharmaceutical, food, and cosmetic industries [20], [30]. The existing delivery systems have been designed to improve the performance of α-TOC with the advantages of low dose frequency and superior bioactivity and stability, for example, in microencapsulation [41], liposomes [29] and as nanoparticles [13]. Multiple methods for encapsulating α-TOC in polymeric nanoparticles have been reported, but studies and applications related to the preparation of α-tocopherol/casein nanoparticles by using ultrasound have not been reported thus far. Moreover, details pertaining to the strength and mechanism of the interaction between casein and α-TOC by ultrasonic treament have not been revealed yet. Thus, the objective of the present study is to determine the ultrasound conditions required to produce more stable α-tocopherol/casein nanoparticles.

Casein is an amphiphilic self-assembling protein, and it offers certain advantages as a natural vehicle for bioactive compounds [3]. The structural and physicochemical properties of casein, have been described, such as the binding of ions and small molecules and excellent emulsification and self-assembly properties [8], [26], [32], [42]. Furthermore, casein reportedly interacts with bioactive compounds, such as blueberry anthocyanins [45] and vitamin A [32]. These reports explore the effects of carriers on bioactive compounds under various processing conditions and their interaction mechanism. The protective effects of casein on the stability and antioxidant capacity of α-TOC and their interaction mechanism are reported in this study. Fourier deconvolution analysis and Gaussian curve fitting are employed to provide detailed information on the structure of casein after ultrasonic treatment.

In contrast to previous reports about nanoparticles, the present study attempts to evaluate the influences of different ultrasound powers and ultrasound times on the particle size, polydispersity index, and protein structure of the encapsulated nanoparticles loaded with α-TOC. The protective effects of casein on the stability and antioxidant capacity of α-TOC are examined. The strength and mechanism of interation between casein and α-TOC are elucidated using different spectroscopic methods and proton spectra. Moreover, the antioxidant ability is employed to produce a grape seed oil emulsion by using the lipid hydroperoxides (LOOH) and thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) assays.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Casein sodium salt, α-TOC (purity of 96%), and 1, 1, 3, 3-tetraethoxypropane were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Cumene hydroperoxide was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). All other chemicals of analytical grade were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Ultrapure water was utilized throughout.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Sample preparation

Self-assembled casein nanoparticles containing α-TOC were prepared as described by Semo et al. [7]. The α-TOC solution was prepared as follows: 0.01, 0.007, and 0.005 g of α-TOC were dissolved separately in 10 mL of anhydrous ethanol, and the resulting solutions were oscillated for 2 min. After the complete dissolution of α-TOC, the solutions were stored in a refrigerator (4 ± 2 °C). Casein was dissolved in distilled water at a concentration of 2 mg/mL. The pH was adjusted to about 10 by using 0.1 mol/L NaOH. This system was stirred at room temperature for 3 h and then stored in a refrigerator (4 ± 2 °C) for 8 h. Thereafter, the system pH was adjusted to about 6.8 by using 0.1 mol/L HCl. Then, α-TOC was added to the system in different mass ratios (Table 1), and the resulting samples were treated in an ultrasonic cell crusher (on 2 s, off 3 s, φ20 mm, XO1200D, China) with different combinations of power (100, 200, 300 W) and treatment duration (5, 10, and 15 min). Approximately 4 mL of 1 mol/L tripotassium citrate, 24 mL of 0.2 mol/L K2HPO4, and 20 mL of 0.2 mol/L CaCl2 were added. Thereafter, four consecutive additions of 2.5 mL of 0.2 mol/L K2HPO4 and 5 mL of 0.2 mol/L CaCl2 were performed at 15-min intervals. During this process, the samples were stirred with a magnetic stirrer, sample temperature was maintained at 37 ℃, and sample pH was adjusted between 6.8 and 7.0 by using either 0.1 mol/L HCl or 0.1 mol/L NaOH. The final dispersions were stirred at 350 r/min for 1 h. The samples were then treated for 20 s at 74 ℃ in a water bath. The control sample was prepared by following the same procedure.

Table 1.

Orthogonal experimental design.

| Column | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Ultrasonic time/min | Ultrasonic power/W | Mass ratio | Control |

| 1 | 5 | 100 | 1:200 | 1 |

| 2 | 5 | 200 | 1:300 | 2 |

| 3 | 5 | 300 | 1:400 | 3 |

| 4 | 10 | 100 | 1:300 | 3 |

| 5 | 10 | 200 | 1:400 | 1 |

| 6 | 10 | 300 | 1:200 | 2 |

| 7 | 15 | 100 | 1:400 | 2 |

| 8 | 15 | 200 | 1:200 | 3 |

| 9 | 15 | 300 | 1:300 | 1 |

2.2.2. Preparation of grape seed oil emulsion

A grape seed oil emulsion was prepared following the method described by Shao & Tang [44]. Oil-in-water emulsions containing grape seed oil (30%, w/w) in the oil phase were produced using a high-speed blender (Fluko, Shanghai, China) operated at 10,000 rpm for 3 min. The oil droplet size was further reduced using a high-pressure homogenizer (Ah-Basic, ATS) operated at 50 MPa. Nanoparticles prepared with a mass ratio of 1:200 were added to the emulsions. The ultrasound treatment power was 300 W, and the duration was 5 min, respectively. The net α-TOC contents were 100 mg/kg and 200 mg/kg, respectively. The mixtures were then homogenized twice at 50 MPa by using a high-pressure homogenizer (Ah-Basic, ATS) to improve nanoparticle distribution in the interfacial regions.

Approximately 3 mL of the emulsions were placed in a professional rancimat (Metrohm, 892, Swiss) and removed at 30-min intervals between 0 and 3 h. Accelerated oxidation conditions were employed. The heater temperature and gas flow rate were set to 60 ℃ and 20 L/h, respectively. The emulsions were prepared in duplicate for the LOOH and TBARS assays.

2.3. Experimental design

An orthogonal rotation combination test design comprising three levels and four factors, namely ultrasonic treatment power, ultrasonic treatment time, mass ratio, and control, was used to optimize the model and reaction conditions (Table 1). Encapsulation efficiency was set as the index of this ultrasound process.

Encapsulation efficiency was determined following a modified version of a procedure described in the literature [19]. Encapsulation efficiency was defined as the difference between the total α-TOC content used during preparation and the free α-TOC content obtained after separation from the medium. Briefly, the suspensions were accurately injected into a centrifugal ultrafiltration device. Filtrates were extracted from the suspensions by means of centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 30 min. Hexane was added to the α-TOC extracted from the filtrate and the resulting mixture was subjected to vortexing. The free α-TOC concentration was assayed using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Agilent, Cary 60, Malaysia) at 297 nm. The encapsulation efficiency (EE, %) was calculated using equation (1):

| (1) |

where Wt is the total amount of α-TOC used during the preparation, and Wf is the amount of free α-TOC in the filtrate.

2.4. UV–Vis spectroscopy and calibration curve

The self-assembled casein nanoparticles were dissolved in phosphate buffer solution (PBS, pH = 7.0) with the final concentration of 0.15 mg/mL. UV–Vis spectra of the solution were recorded with a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Agilent, Cary 60, Malaysia) scanning from 190 to 400 nm at room temperature. The scan resolution was 0.5 nm, scanning step was 1 nm, and scanning rate was 50 nm/min. PBS was used as a blank control [24], [27].

A absorbance vs concentration calibration curve was plotted for different concentrations of α-TOC dissolved in hexane. Initially, 200 mg of α-TOC was accurately weighed, and the volume was eventually increased to 100 mL by adding hexane. Then, 1 mL of the solution was placed in a 10-mL volumetric flask, and the volume of this solution was eventually increased to 10 mL by adding hexane; the resulting solution was called the working solution. Approximately 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, and 2.5 mL of the working solution were accurately weighed and eventually diluted to 10 mL by using hexane. The absorbance of the diluted samples was assayed using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Agilent, Cary 60, Malaysia) at 297 nm. A hexane sample was used as the blank control. The standard curve was plotted with the mass concentration of α-TOC as the abscissa and its absorbance as the ordinate. The following one-dimensional linear regression equation was obtained: y = 15.737x + 0.0252, R2 = 0.9963.

2.5. Proton spectra

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recoded using a Bruker Avance III HD instrument. 1H NMR spectra were obtained with a spectral width of 500 MHz, acquisition time of 3.9 s, delay of 2 s, and pulse angle of 45°. The proton spectrum analysis was performed with a total of 16 scans.

2.6. Size determination

The particle size and PDI of the α-TOC/CN nanoparticles were measured after the resuspension of lyophilized nanoparticles by using the modified method reported by Zigoneanu et al. [13]. The particle size and PDI of both casein and α-TOC/CN nanoparticles were determined with dynamic light scattering (Nano ZS, Malvern, UK) by using a He/Ne laser (λ = 632.8 nm). Particle size analysis of the emulsion droplets was performed at 25℃ by following a previously described procedure [39]. All measurements were repeated thrice.

2.7. Fluorescence spectroscopy

The molar concentration ratio of α-TOC to casein was set variously to 3:1, 4:1, and 5:1. Fluorescence spectroscopy was performed using a spectrofluorometer (Gangdong, F-280, China) scanning from 250 to 380 nm at the excitation wavelengths of 280 nm and 295 nm. The excitation and emission bandwidth was 10 nm, and the scan speed was 60 nm/min; PBS was used as the blank control [2], [47].

2.8. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) analysis was performed using a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (Shimadzu, IR Affinity-1, Japan) scanning from 4,000 to 400 cm−1 at room temperature. KBr was pressed into plates and solution samples were dripped onto these plates for measurement. The analysis was performed with a total of 32 scans at the resolution of 4 cm−1.

2.9. Stability testing

To investigate nanoparticle stability, stability tests were conducted under modified versions of four conditions described in the literature [19], [29], [45]. A photo stability test was conducted by exposing the samples to an illumination intensity of 15 W for 180 min. A thermal treatment stability test was conducted by heating the samples in an air dry oven at 50 °C for 6 h. Storage stability tests were conducted for 6 d at room temperature (20 ± 2 °C) and in a refrigerator (4 ± 2 °C). The stability of the self-assembled casein nanoparticles was compared with that of the free α-TOC.

The retention rate was presented as the remaining absorbance with time of exposure. The nanoparticle samples treated under the four aforementioned conditions were mixed with anhydrous ethanol in equal volume with stirring, and 200 μL of 1 mol/L NaOH was added into the mixtures. α-TOC was extracted from the emulsions by using hexane until the water phase was colorless and transparent, and the free α-TOC concentration was assayed using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Agilent, Cary 60, Malaysia) at 297 nm.

2.10. Antioxidant activity testing

LOOH was determined according to a previously described procedure [37]. A sample (0.3 mL) was mixed in a glass tube with 1.5 mL isooctyl alcohol-isopropanol (3:1, v/v) on a vortex mixer for 10 s and centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 10 min to separate the phases. A 200-μl sample of the resulting supernatant (organic phase) was mixed thoroughly with 2.8 mL of methanol-butyl alcohol (2:1, v/v). Ammonium thiocyanate solution (50 μL, 3.94 mol/L) was added to the resulting mixture. Then, 50 μL of iron (II) solution was added, and the resulting mixture was mixed using a vortex mixer for 5 s. After incubation for 20 min at room temperature with appropriate stirring, the absorbance of the sample was determined at 510 nm against a blank that contained all of the reagents except for the sample by using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Agilent, Cary 60, Malaysia). LOOH concentrations were determined from a standard curve prepared using cumene hydroperoxide.

The secondary oxidation products were monitored with the thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) method by following a procedure described elsewhere [37], [48]. Approximately 2 mL of each sample was mixed with 4 mL of TBA reagent containing 15% w/v trichloloracetic acid and 0.375% w/v thiobarbituric acid in 0.25 mol/L HCl in screw-capped tubes and placed in a boiling water bath for 15 min. The samples were then cooled to room temperature and centrifuged at 1,600 g for 20 min. The absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 532 nm by using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Agilent, Cary 60, Malaysia). The TBARS concentrations were determined from a standard curve prepared using 1,1,3,3-tetraethoxypropane.

2.11. Statistical analysis

The experimental data were statistically analyzed and expressed using SPSS20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). All diagrams were plotted using Origin 8.1 software (Microcal, USA). The significance correlations were defined as (p < 0.05) and (p < 0.01).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. UV–Vis spectra of casein after binding with α-TOC

The interaction of small molecules with protein was investigated by means of UV–Vis spectroscopy to confirm the structural changes that occurred in the protein during ultrasonic treatment. Changes in the peak wavelength and absorption spectral intensity of the small molecules with protein represent the strength and mechanism of the interaction.

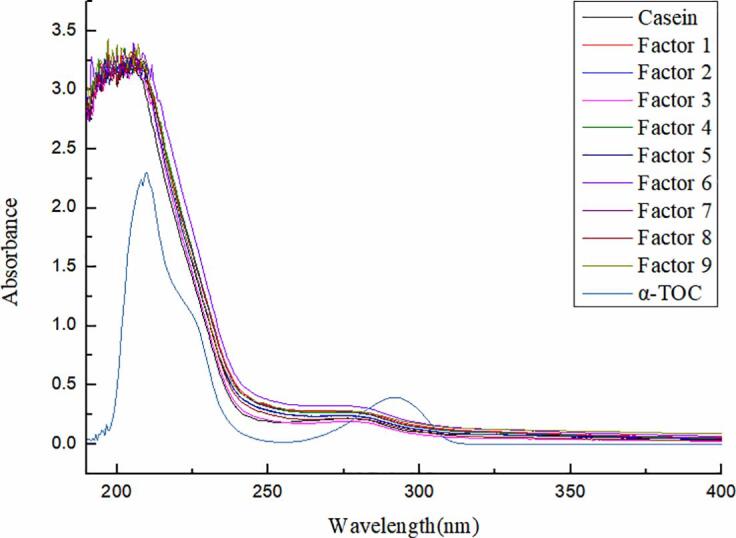

The UV–Vis spectra of α-TOC/CN nanoparticles exhibited significant changes (Fig. 1). Two distinct characteristic absorption peaks were observed in the wavelength ranges of 195.5–212 nm and 275.5–285.5 nm. The former wavelength range was mainly characterized by changes in peptide bonds, that is, the α-helix structure of protein, while the latter wavelength was mainly characterized by the absorption peaks of chromogenic groups such as tryptophan and tyrosine [34]. The absorbance intensities of α-TOC/CN nanoparticles was different during intensity measurements in the case of all of the ultrasonic treatments investigated herein (Fig. 1). A possible reason is that the hydrophobic groups in denatured proteins were exposed upon ultrasonic treatment [11], [35], resulting in increased fluorescence intensity. Fig. 1 shows that the maximum absorption wavelength (195.5–212 nm) of the system increased with the addition of α-TOC, which led to the formation of α-TOC/CN. These results agreed with those of Tang et al. [22], who reported that the absorption wavelength of C3G-BSA increased with the addition of C3G. The secondary structure of casein was affected by the newly formed compound [22]. As reported by Hu et al. [11] and Zhang et al. [35], the functional properties of protein can be modified with ultrasound treatment, which induces several secondary structural changes as well. These effects of ultrasound are consistent with the results reported in the literature, wherein the mechanism of ultrasound was confirmed [10], [11], [16], [35].

Fig. 1.

The changes of UV–Vis spectra under orthogonal experimental design.

The untreated samples formed more elastic and compact dispersions, while the ultrasonic-treated samples formed more viscous and loosened dispersions. This is because as the ultrasonic treatment time and power increase, as a protein denatured, more hydrophobic groups are exposed due to the instantaneous extreme temperatures and pressures generated by ultrasound [14], [35]. Moreover, the results indicated that the optimum orthogonal array design analysis conditions were as follows: Ultrasonic power = 300 W, ultrasonic treatment time = 5 min, and mass ratio = 1:200. The nanoparticles prepared using the optimized conditions exhibited an encapsulation efficiency of 97.29 ± 5.2%. These results suggest that there is a balance between the aggregation and exposure of hydrophobic groups [4], resulting in the formation of self-assembled nanoparticles with a hydrophobic core, which could be ideal nanoscale carriers for lipophilic drugs [3], [23].

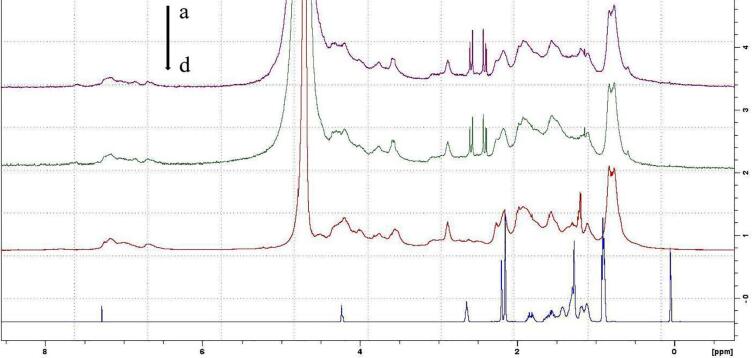

3.2. Proton spectra

The two purified products (α-TOC and casein) and α-TOC/CN nanoparticles were characterized with 1H NMR. The chemical shifts were read and are presented in Fig. 2. Compared to the free samples, the nanoparticles exhibit the chemical shifts of conjugated double bonds, as can be observed from their spectrum. A combined analysis of UV, Fluorescence spectra and NMR data confirmed the binding of casein to α-TOC.

Fig. 2.

1H NMR spectrum of samples. (a) α-TOC/CN nanoparticles without ultrasound, (b) α-TOC/CN nanoparticles with ultrasound, (c) casein, (d) α-TOC.

3.3. Size determination

As summarized in Table 2, the average diameters of the casein particles were 198.40 ± 0.56 nm and 170.93 ± 1.86 nm with and without ultrasound treatment, respectively. The average PDI of the α-TOC/CN nanoparticles (under optimum conditions) was 0.24 ± 0.02, which was slightly smaller. Madadlou et al. [5] observed similar results for casein micelles, which indicates that the homogeneity of the particles increased owing to sonication. Nanoparticles were added into the formed emulsions post-treatment by using a high-pressure homogenizer. The emulsions produced with the net α-TOC content of 100 mg/kg had a mean droplet size of 296.07 ± 15.14 nm, whereas the emulsions produced with the net α-TOC content of 200 mg/kg had a smaller mean droplet size of 251.43 ± 16.97 nm. A possible reason was that the mean droplet size decreased as the amount of casein added increased [39].

Table 2.

Change of particle size and PDI of casein solution as a result of sonication.

| particle size (nm) | PDI | |

|---|---|---|

| Casein (without ultrasound treatment) | 198.40 ± 0.56 | 0.40 ± 0.01 |

| α-Tocopherol/casein nanoparticles (with ultrasound treatment) | 170.93 ± 1.86 | 0.24 ± 0.02 |

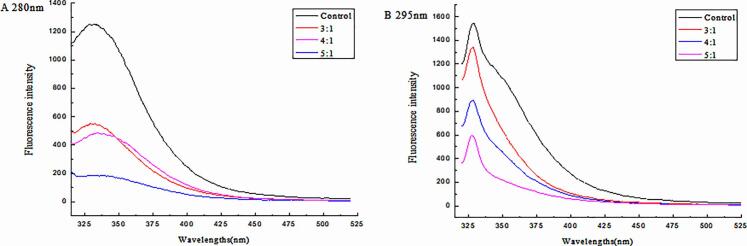

3.4. Fluorescence spectra of casein after binding with α-TOC

Information about the binding properties of small molecules to protein, such as the binding mechanism, binding model, binding constant, and binding sites, can be gleaned from their fluorescence spectra [46]. The fluorescence spectra of nanoparticles recorded at 280 nm and 295 nm in the presence of different molar concentrations of α-TOC are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The changes of fluorescence spectra under different molar concentration ratio.

The fluorescence intensity of a protein can mainly be ascribed to the Trp, Tyr, and Phe residues [9], [23]. According to Fig. 3, the fluorescence intensity of casein decreases regularly with a gradual increase in the α-TOC concentration, indicating that the interaction between casein and α-TOC occurred, and α-TOC/CN complexes were formed. Liang, Tremblay-Hebert, & Subirade [21] reported that binding of α-tocopherol to β-lg which reduced the turbidity and improved the solubility of fat-soluble vitamins and that the fluorescence intensity decreased with the addition of α-tocopherol. In addition, when the excitation wavelength was 280 nm (Fig. 3A), the maximum emission wavelength of casein exhibited a red shift, which indicated that the chromophore of casein was placed in a more hydrophobic environment upon the addition of α-TOC. Changes to the protein structure were more remarkable, and the structure was more relaxed and loose [1], [25]. When the excitation wavelength was 295 nm (Fig. 3 B), the maximum emission wavelength of casein did not present a red or blue shift. According to the literature, the major amino acids involved in the interaction of protein with hydrophobic compounds are Tyr, Phe, Trp, Leu, and Val. Moreover, reassembly enhanced the bond between α-TOC and hydrophobic protein groups. These structural and physicochemical properties of proteins facilitate their functionality as carriers if different bioactive compounds and micronutrients [3], [43]. Esmaili et al. [23] encapsulated thehydrophobic curcumin with amphiphilic self-assembling protein, and as a result, the solubility, bioavailability, and antioxidant activity of curcumin increased. For this reason, the present study worked to improve the binding ability of this modified protein because hydrophobic interactions are major forces that occur during the interaction of α-TOC with protein.

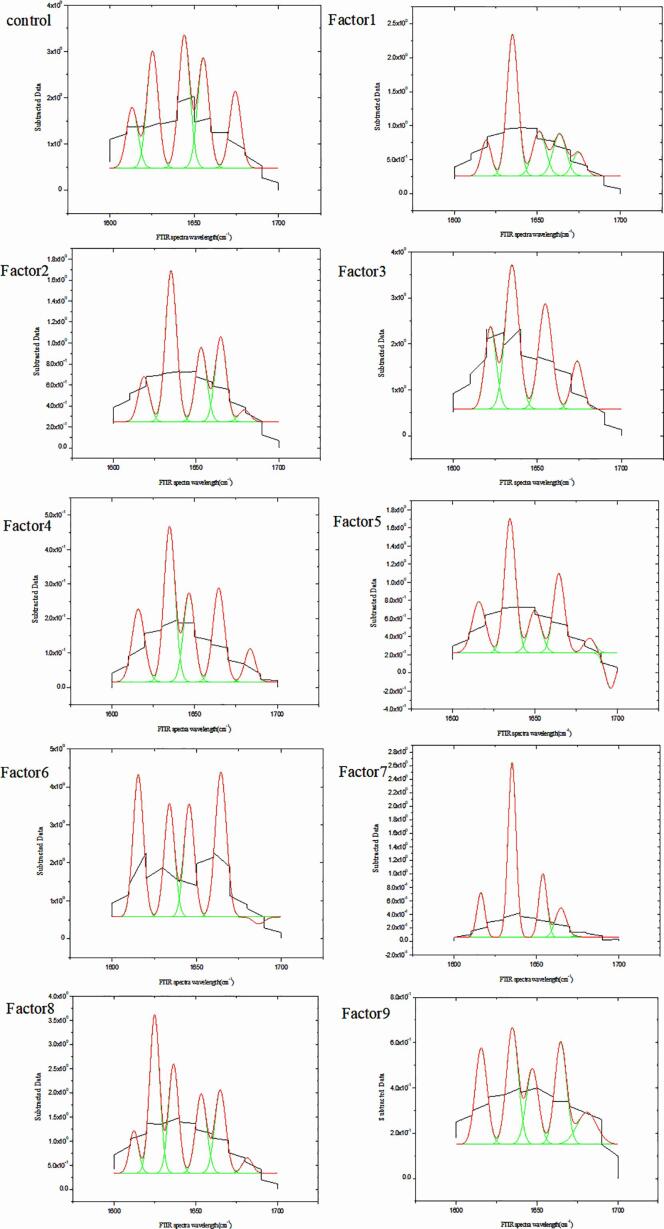

3.5. FTIR characterization of casein after binding with α-TOC

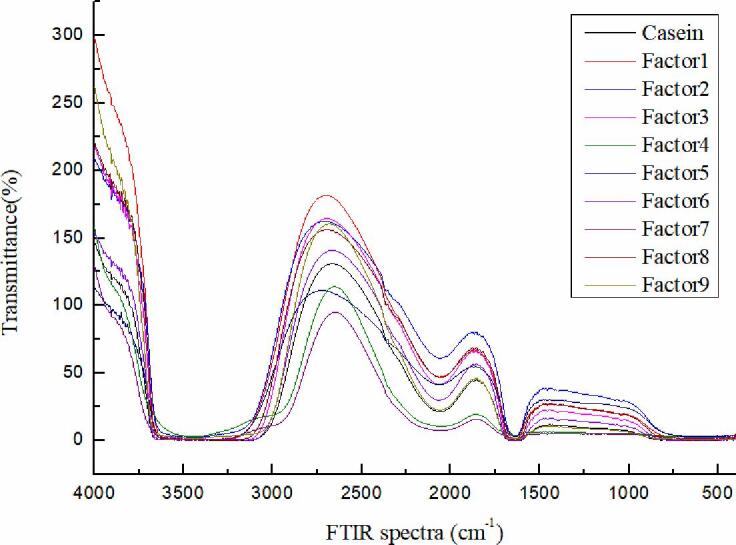

The FTIR spectra of proteins exhibit a number of amide bands that represent different vibrations of peptide moieties, such as the bands corresponding to amide I (1,600–1,700 cm−1, mainly C = O stretch), amide II (1,600–1,500 cm−1, C–N stretch coupled with N–H bending mode), amide III (1,330–1,220 cm−1, C–N stretching vibration and N–H deformation of peptide group) [18], [36], [40].

The FTIR spectra of the α-TOC/CN nanoparticles is shown in Fig. 4. The peak positions of amide I bands are shifted in the infrared spectrum of casein after the interaction of casein with α-TOC. The changes to these peak positions and peak shapes demonstrated that the secondary structure of casein was altered, indicating the occurrence of an interaction between α-TOC and casein.

Fig. 4.

The changes of FTIR spectra under orthogonal experimental design.

When both criteria I and II were fulfilled and the integral areas of the amide I band were normalized, it was possible to use the relative areas of the deconvoluted amide I bands to directly determine the relative amounts of different types of secondary structures. As shown in Fig. 5, Fourier deconvolution analysis and Gaussian curve fitting were performed to obtain detailed information about the protein structure.

Fig. 5.

The Fourier deconvolution analysis and Gaussian curve fitting.

Before estimation of the percentage content of each secondary structure, the component bands should be assigned. The band 1,650–1 658 cm−1 is typically assigned to the α-helix structure. In case of the β-sheet structure, the amide I band is generally in the range of 1,610–1,640 cm−1. The peaks of the random coil and β-turn structures can be found within the ranges of 1,640–1,650 cm−1 and 1,660–1,700 cm−1 [15], [17]). A quantitative analysis of each secondary structure was performed considering the integrated areas of the component bands in amide I, as summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Changes of secondary structure content.

| Test | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio of α-helix to β-sheet | 0.62 | 0.301 | 0.378 | 0.494 | 0.374 | 0.246 | 0.442 | 0.29 | 0.285 | 0.378 |

The ratio of α-helix to β-sheet structures in casein was 0.62; in case of the α-TOC/CN nanoparticles, the ratio decreased to 0.246–0.494. These results indicated that the flexibility of the internal structure of the protein increased.

3.6. Stability of α-TOC/CN nanoparticles

According to Table 4, the storage stabilities of the nanoparticles investigated under four conditions are significantly different.

Table 4.

Stability testing of nanoparticles with defferent treatments (presented as the remaining absorbance in each fraction with time of exposure)

| Treatment time | In a refrigerator (4 °C) |

At room temperature |

Exposure time | UV light |

Treatment time | In a air dry oven(50℃) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanoparticles | α-TOC (control) | Nanoparticles | α-TOC (control) | Nanoparticles | α-TOC (control) | Nanoparticles | α-TOC (control) | |||

| 0d | 0.914 ± 0.009 aA | 0.528 ± 0.020 aD | 0.910 ± 0.005 aA | 0.528 ± 0.020 aD | 0 min | 0.863 ± 0.009 aB | 0.795 ± 0.005 aC | 0 h | 0.864 ± 0.008 aB | 0.773 ± 0.018 aC |

| 1d | 0.819 ± 0.030 bB | 0.45933 ± 0.011bE | 0.866 ± 0.009 bA | 0.433 ± 0.029 bE | 30 min | 0.819 ± 0.011 abB | 0.732 ± 0.015 aC | 1 h | 0.732 ± 0.027 bC | 0.578 ± 0.035 bD |

| 2d | 0.761 ± 0.020 cA | 0.387 ± 0.016cD | 0.786 ± 0.018 cA | 0.389 ± 0.012cD | 60 min | 0.800 ± 0.003 bA | 0.619 ± 0.028 bB | 2 h | 0.617 ± 0.047 cB | 0.467 ± 0.041 cC |

| 3d | 0.685 ± 0.022 dA | 0.321 ± 0.023 dCD | 0.691 ± 0.020 dA | 0.298 ± 0.014 dD | 90 min | 0.700 ± 0.012 cA | 0.519 ± 0.032 cB | 3 h | 0.498 ± 0.014 dB | 0.351 ± 0.034 dC |

| 4d | 0.589 ± 0.017 eA | 0.243 ± 0.011 eC | 0.594 ± 0.024 eA | 0.233 ± 0.013 eC | 120 min | 0.546 ± 0.067 dA | 0.418 ± 0.005 cB | 4 h | 0.432 ± 0.019 eB | 0.249 ± 0.035 eC |

| 5d | 0.495 ± 0.008 fA | 0.195 ± 0.009 fE | 0.504 ± 0.009 fA | 0.188 ± 0.007 fE | 150 min | 0.410 ± 0.012 eB | 0.299 ± 0.020 eD | 5 h | 0.336 ± 0.034 fC | 0.205 ± 0.008 efE |

| 6d | 0.398 ± 0.020 gA | 0.167 ± 0.013 fDE | 0.388 ± 0.013 gAB | 0.101 ± 0.020 gE | 180 min | 0.3197 ± 0.007 fBC | 0.320 ± 0.092 eC | 6 h | 0.208 ± 0.006 gD | 0.183 ± 0.006 fD |

Each value is expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The values not statistically different are accompanied by the same letter and the values statistically different with another letter as compared to control (Small letter represent intra-group, capital letter represent inter-group).

As the storage time increased from 1 to 6 h, the retention rate of the self-assembled nanoparticles decreased by 10.39% and 56.43%. Moreover, the retention rate of free α-TOC decreased by 1.21–1.26 times from 13.06% to 68.39% as the storage time in the refrigerator (4 °C) increased.

The retention rates of the self-assembled casein nanoparticles and the free α-TOC were 42.65% and 19.05% (6d) at room temperature, respectively. However, the storage stability exhibited the similar trends at room temperature and in a refrigerator (4 ± 2 °C), and the difference between the two stability values was not significant. However, compared to the first two treatments, temperature and oxygen has stronger effects on the thermal stability of the two samples (in an air dry oven at 50 °C), and the loss of retention rate (75.93%) was the most highest from 0 to 6 h.

When the samples were exposed to ultraviolet light, the retention rate exhibited a variation trend similar to those of the self-assembled nanoparticles and free α-TOC, and the retention rate decreased from 5.13% to 62.95% and from 7.85% to 61.37%, respectively. The retention rate of the self-assembled nanoparticles was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than that of the free α-TOC, which was ascribed to the fact that self-assembled nanoparticles can protect α-TOC from the degradation caused by ultraviolet light, oxygen, temperature. Lang et al. [45] observed similar results for casein, that is, the increasing stability of blueberry anthocyanins due to α-casein or β-casein was outstanding under thermal and photo conditions. α-Tocopherol decomposes easily through oxidation when exposed to mitigating conditions, such as high temperature, oxygen, and light [28]. Previous studies indicate that the stability of the α-tocopherol released from cold-set β-LG emulsion gels is considerably superior to that of free compounds [20].

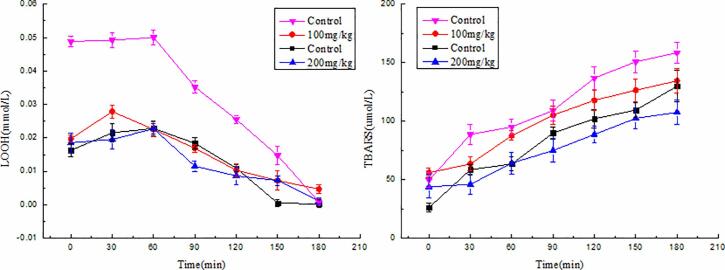

3.7. Antioxidant activity testing

The effect of α-TOC/CN nanoparticles and free α-TOC on the formation of both LOOH and TBARS is shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Evolution of LOOH and TBARS in the four types of stabilized emulsions upon accelerated storage up to 180 min.

Both concentrations of α-TOC/CN nanoparticles were able to inhibit lipid oxidation in the oil-in-water emulsion, as determined by both LOOH and TBARS assays. With the passage of time, the concentrations of LOOH, the primary products of oil oxidation in the emulsion, first increased and then decreased. When the free α-TOC concentration was 100 mg/kg, the primary oxidation rate of oil was the highest, and the LOOH concentrations in the emulsion gradually increased to their maximum values with extension of the treatment time beyond 60 min. LOOH concentrations remained at a low level throughout the course of the study in emulsions containing 200 mg α-TOC/kg oil with the nanoparticles. The presence of 100 and 200 mg α-TOC/kg oil led to a 78.54 and 63.54 μmol/L inhibition of TBARS formation with the nanoparticles, respectively, vs the free samples containing control after 180 mins. The increases in TBARS values were the greatest for the control samples with free α-TOC, followed by the nanoparticles with a concentration of 100 mg/kg. Treatment with 200 mg/kg of nanoparticles led to smaller increases in the TBARS values of grape seed oil emulsion systems compared to those of the control samples. The reaction time could have promoted the decomposition of lipid hydroperoxides such that they did not accumulate but were instead converted to secondary lipid oxidation products, which were observed as high TBARS values. From these results shown, we can conclude that during accelerated oxidation treatment, more rapid molecular degradation of the free α-TOC samples occurred due to temperature and air, leading to the formation of oxidation radicals in oil. Lipid oxidation is one the major causes of food spoilage, and fats and oils in processed foods are typically used in emulsion form [38]. Therefore, one strategy to inhibit lipid oxidation in oil-in-water emulsions is to use food additives that can bind and trap free radicals. Similar findings were reported for other oil emulsions, for example, at the oil–water interface, resveratrol can protect the oil by simply reacting with oxidizing agents [12]. Esmaili et al. [23] observed similar results for curcumin, in that the antioxidant activity of curcumin encapsulated in Beta-CN was higher than those of the two free samples.

4. Conclusions

Changes in UV–Vis spectra were recorded with two maxima at wavelengths of 195.5–212 nm and 275.5–285.5 nm. The results of UV–Vis fluorescence spectrometry indicated that the secondary structure of casein changed in the presence of α-TOC. The results of proton spectra indicated that the nanoparticles exhibited the chemical shifts of conjugated double bonds. The fluorescence intensities of casein decreased gradually with increasing α-TOC concentrations, and the intrinsic fluorescence of casein was quenched by α-TOC in a static pattern. The size and PDI of the particles changed significantly with ultrasonic treatment (300 W, 5 min). Fourier deconvolution analysis and Gaussian curve fitting provided detailed information of the protein structures observed under different levels of treatment power (0, 100, 200, 300 W) and various treatment times (0, 5, 10, and 15 min). The ratio of α-helix to β-sheet secondary structures decreased from 0.62 to 0.246, which indicated that the structure of casein became more flexible. Under typical processing and storage conditions (thermal, photo, 20 ± 2 °C and 4 ± 2 °C), the stability of α-TOC increased due to its interaction with casein. The effects of casein on the antioxidant ability of α-TOC were investigated using LOOH and TBARS assays, and the results represent remarkable outcomes.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Libin Sun: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition. Hong Wang: Investigation, Data curation, Project administration. Xiang Li: Visualization. Sheng Lan: Formal analysis. Junguo Wang: Methodology, Formal analysis, Resources. Dianyu Yu: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No: 32072259), Heilongjiang Provincial Science and Technology Department (No:2020ZX08B01), special research funds of Jilin Business And Technology College of China (No:K2020003, LSK2020010).

References

- 1.Mohamed A., Hojilla-Evangelista M.P., Peterson S.C., Biresaw G. Barley protein isolate:thermal, functional, rheological, and surface properties. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2007;84(3):281–288. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sahu A., Kasoju N., Bora U. Fluorescence study of the curcumin−casein micelle complexation and its application as a drug nanocarrier to cancer cells. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9(10):2905–2912. doi: 10.1021/bm800683f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elzoghby A.O., Abo W.S., El-Fotoh N.A., Elgindy Casein-based formulations as promising controlled release drug delivery systems. J. Control. Release. 2011;153:206–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soria Ana Cristina, Villamiel Mar. Effect of ultrasound on the technological properties and bioactivity of food: a review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2010;21(7):323–331. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madadlou Ashkan, Mousavi Mohammad Ebrahimzadeh, Emam-djomeh Zahra, Ehsani Mohammadreza, Sheehan David. Sonodisruption of re-assembled casein micelles at different pH values. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2009;16(5):644–648. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2008.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noronha Carolina Montanheiro, Granada Andrea Ferreira, Carvalho Sabrina Matosde, Lino Renata Calegari, Matheus Viniciusde O.B., Maciel Pedro Luiz, ManiqueBarreto Optimization of α-tocopherol loaded nanocapsules by the nanoprecipitation method. Ind. Crops Products. 2013;50:896–903. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Semo E., Kesselman E., Danino D., Livney Y. Casein micelle as a natural nano-capsular vehicle for nutraceuticals. Food Hydrocolloids. 2007;21(5-6):936–942. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farnaz Ahmadzadeh Nobari Azar, Akram Pezeshki, Babak Ghanbarzadeh, Hamed Hamishehkar, Maryam Mohammadi, Saeid Hamdipour, Hesam Daliri. Pectin-sodium caseinat hydrogel containing olive leaf extract-nano lipid carrier: Preparation, characterization and rheological properties, LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 148 2021 111757.

- 9.Sheng Feng, Wang Yuning, Zhao Xingchen, Tian Na, Hu Huali, Li Pengxia. Separation and identification of anthocyanin extracted from mulberry fruit and the pigment binding properties toward human serum albumin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014;62(28):6813–6819. doi: 10.1021/jf500705s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kresic Greta, Lelas Vesna, Jambrak Anet Režek, Herceg Zoran, Brnčić Suzana Rimac. Influence of novel food processing technologies on the rheological and thermophysical properties of whey proteins. J. Food Eng. 2008;87(1):64–73. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu Hao, Wu Jiahui, Li-Chan Eunice C.Y., Zhu Le, Zhang Fang, Xu Xiaoyun, Fan Gang, Wang Lufeng, Huang Xingjian, Pan Siyi. Effects of ultrasound on structural and physical properties of soy protein isolate (SPI) dispersions. Food Hydrocolloid. 2013;30(2):647–655. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Haixia, Fan Qi, Li Di, Chen Xing, Liang Li. Impact of gum Arabic on the partition and stability of resveratrol in sunflower oil emulsions stabilized by whey protein isolate. Colloids Surf. B: Biointerfaces. 2019;181:749–755. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2019.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zigoneanu Imola Gabriela, Astete Carlos Ernesto, Sabliov Cristina Mirela. Nanoparticles with entrapped a-tocopherol: synthesis, characterization, and controlled release. Nanotechnology. 2008;19 doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/10/105606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuchlyan Jagannath, Kundu Niloy, Banik Debasis, Roy Arpita, Sarkar Nilmoni, Kuchlyan J., Kundu N., Banik D. Spectroscopy and Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy To Probe the Interaction of Bovine Serum Albumin with Graphene Oxide. Langmuir ACS J. Surf. Colloids. 2015;31:13793–13801. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b03648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang Jianghong, Luan Feng, Chen Xingguo. Binding analysis of glycyrrhetinic acid to human serum albumin: Fluorescence spectroscopy, FTIR, and molecular modeling. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006;14(9):3210–3217. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu Jianmei, Ahmedna Mohamed, Goktepe Ipek. Peanut protein concentrate: production and functional properties as affected by processing. Food Chem. 2007;103(1):121–129. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng Jing-li, Jia Feng, Wang Jin-shui, Gao Yun-fang, Zhou Xiao-pei, Li Xiao-wei. Effect of ultrasonic on the structural properties of casein. China Dairy Ind. 2015;43:20–23. (in Chinese with English abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim Rahmelow, Wigand Hübner.Secondary structure determination of proteins in aqueous solution by infrared spectroscopy: a comparison of multivariate data analysis methods, 241 1996 5-13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Basiri Ladan, Rajabzadeh Ghadir, Bostan Aram. α-Tocopherol-loaded niosome prepared by heating method and its release behavior. Food Chem. 2017;221:620–628. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.11.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Liang, Valerie Leung, S. Line, G.E. Remondetto, M. Subirade. In vitro release of alpha tocopherol from emulsion-loaded b-lactoglobulin gels, Int. Dairy J. 20 2010 176-181.

- 21.Liang Li, Tremblay-Hebert Vanessa, Subirade Muriel. Characterisation of the b-lactoglobulin/a-tocopherol complex and its impact on a-tocopherol stability. Food Chem. 2011;126:821–826. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang Lin, Zhang Dong, Xu Shanhua, Zuo Huijun, Zuo Chunlin, Li Yufei. Different spectroscopic and molecular modeling studies on the interaction between cyanidin3-O-glucoside and bovine serum albumin. Luminescence. 2014;29(2):168–175. doi: 10.1002/bio.2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Esmaili Mansoore, Ghaffari S. Mahmood, Moosavi-Movahedi Zeinab, Atri Malihe Sadat, Sharifizadeh Ahmad, Farhadi Mohammad, Yousefi Reza, Chobert Jean-Marc, Haertlé Thomas, Moosavi-Movahedi Ali Akbar. Beta casein-micelle as a nano vehicle for solubility enhancement of curcumin;food industry application. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2011;44(10):2166–2172. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marsanasco Marina, Márquez Andrés L., Wagner Jorge R., Silvia del V., Alonso Nadia S., Chiaramoni Liposomes as vehicles for vitamins E and C: an alternative to fortify orange juice and offer vitamin C protection after heat treatment. Food Res. Int. 2011;44:3039–3046. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corzo-Martínez Marta, Montilla Antonia, Megías-Pérez Roberto, Olano Agustín, Moreno F. Javier, Villamiel Mar. Impact of high-intensity ultrasound on the formation of lactulose and Maillard reaction glycoconjugates. Food Chem. 2014;157:186–192. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Betz Michael, Kulozik Ulrich. Whey protein gels for the entrapment of bioactive anthocyanins from bilberry extract. Int. Dairy J. 2011;21(9):703–710. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Mingmao, Liu Yan, Cao Huan, Song Ling, Zhang Qiqing. The secondary and aggregation structural changes of BSA induced by trivalent chromium: a biophysical study. J. Luminescence. 2015;158:116–124. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miquel Esther, Alegría Amparo, Barberá Reyes, Farré Rosaura, Clemente Gonzalo. Stability of tocopherols in adapted milk-based infant formulas during storage. Int. Dairy J. 2004;14(11):1003–1011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohammad Ali Sahari, Hamid Reza Moghimi, Zahra Hadian, Mohsen Barzegar, Abdorreza Mohammadi. Physicochemical properties and antioxidant activity of a-tocopherol loaded nanoliposome’s containing DHA and EPA, Food Chem. 215 2017 157-164. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Mohamed Eid, Remah Sobhy, Peiyuan Zhou, Xianling Wei, Di Wu, Bin Li. β-cyclodextrin-soy soluble polysaccharide based core-shell bionanocomposites hydrogel for vitamin E swelling controlled delivery, Food Hydrocolloids 104 2020 105751.

- 31.Torres Pamela, Kunamneni Adinarayana, Ballesteros Antonio, Plou Francisco J. Enzymatic modification for ascorbic acid and alpha-tocopherol to enhance their stability in food and nutritional applications. Open Food Sci. J. 2008;2(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bourassa P., N’soukpoé-Kossi C.N., Tajmir-Riahi H.A. Binding of vitamin A with milk alpha- and beta-caseins. Food Chem. 2013;138:444–453. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.10.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boonnoy Phansiri, Karttunen Mikko, Wong-ekkabut Jirasak. Alpha-tocopherol inhibits poreformation in oxidized bilayers. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017;19(8):5699–5704. doi: 10.1039/c6cp08051k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xia Qina. Northeast Agricultural University; Harbin: 2019. Effects of Ultrasonic Pretreatment Combined with Maillard Reaction on Antioxidant Activity of Casein and Its Enzymatic Hydrolysates. (in Chinese with English abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Qiu-Ting, Tu Zong-Cai, Xiao Hui, Wang Hui, Huang Xiao-Qin, Liu Guang-Xian, Liu Cheng-Mei, Shi Yan, Fan Liang-Liang, Lin De-Rong. Influence of ultrasonic treatment on the structure and emulsifying properties of peanut protein isolate. Food Bioproducts Process. 2013;92(1):30–37. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sonawane Raju Onkar, Patil Savita Dattatraya. Gelatin-κ-carrageenan polyelectrolyte complex hydrogel compositions for the design and development of extended release pellets. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2017;66(16):812–823. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mcdonald Richard E., Hultin Herbert O. Some characteristics of the enzymic lipid peroxidation system in the microsomal fraction of flounder skeletal muscle. J. Food Sci. 1987;52(1):15–21. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elias Ryan J., McClements D. Julian, Decker Eric A. Antioxidant activity of cysteine, tryptophan, and methionine residues in continuous phase β-lactoglobulin in oil-in-water emulsions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005;53(26):10248–10253. doi: 10.1021/jf0521698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’ Dwyer Sandra P., O’ Beirne David, Eidhin Deirdre Ní, O’ Kennedy Brendan T. Effects of sodium caseinate concentration and storage conditions on the oxidative stability of oil-in-water emulsions. Food Chem. 2013;138(2-3):1145–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.09.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sirotkin Vladimir A, Zinatullin Albert N, Solomonov Boris N, Faizullin Djihanguir A, Fedotov Vladimir D. Calorimetric and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic study of solid proteins immersed in low water organic solvents. Biochimica et Biophysica. 2001;1547(2):359–369. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(01)00201-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoo Sang-Ho, Song Young-Bin, Chang Pahn-Shick, Lee Hyeon Gyu. Microencapsulation of alphatocopherol using sodium alginate and its controlled release properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2006;38:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sarantis Stelios D., Eren Necla Mine, Kowalcyk Barbara, Jiménez-Flores Rafael. Thermodynamic interactions of micellar casein and oat β-glucan in a model food system. Food Hydrocolloids. 2020;115 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Livney Yoav D. Milk proteins as vehicles for bioactives. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2010;15(1-2):73–83. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shao Yun, Tang Chuan-He. Characteristics and oxidative stability of soy protein-stabilized oil-in-water emulsions: Influence of ionic strength and heat pretreatment. Food Hydrocolloids. 2014;37:149–158. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lang Yuxi, Gao Haiyan, Tian Jinlong, Shu Chi, Sun Renyan, Li Bin, Meng Xianjun. Protective effects of α-casein or β-casein on the stability and antioxidant capacity of blueberry anthocyanins and their interaction mechanism. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2019;115:108434. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2019.108434. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Zhen, Chen Junhui, Wang Shaobin, Chen Zhanguang. Characterizing the interaction between oridonin and bovine serum albumin by a hybrid spectroscopic approach. J. Luminescence. 2013;134:863–869. [Google Scholar]

- 47.He Zhiyong, Chen Jie, Moser Sydney E., Jones Owen G., Ferruzzi Mario G. Interaction of β-casein with (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate assayed by fluorescence quenching: Effect of thermal processing temperature. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016;51(2):342–348. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen Bingcan, McClements David Julian, Decker Eric Andrew. Role of Continuous Phase Anionic Polysaccharides on the Oxidative Stability of Menhaden Oil-in-Water Emulsions. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2010;58:3779–3784. doi: 10.1021/jf9037166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]