Abstract

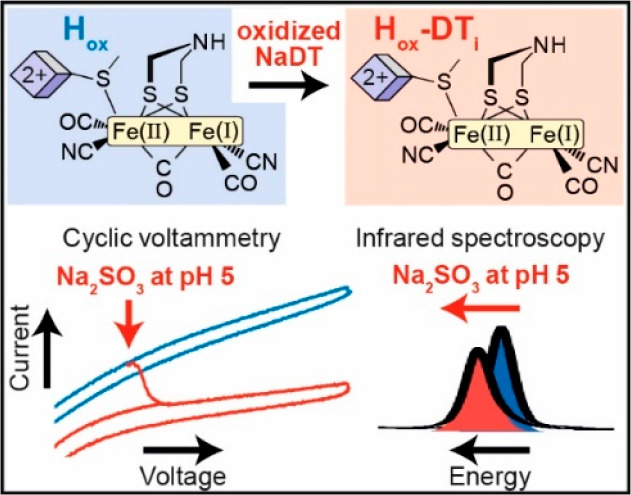

[FeFe] hydrogenases are highly active enzymes for interconverting protons and electrons with hydrogen (H2). Their active site H-cluster is formed of a canonical [4Fe-4S] cluster ([4Fe-4S]H) covalently attached to a unique [2Fe] subcluster ([2Fe]H), where both sites are redox active. Heterolytic splitting and formation of H2 takes place at [2Fe]H, while [4Fe-4S]H stores electrons. The detailed catalytic mechanism of these enzymes is under intense investigation, with two dominant models existing in the literature. In one model, an alternative form of the active oxidized state Hox, named HoxH, which forms at low pH in the presence of the nonphysiological reductant sodium dithionite (NaDT), is believed to play a crucial role. HoxH was previously suggested to have a protonated [4Fe-4S]H. Here, we show that HoxH forms by simple addition of sodium sulfite (Na2SO3, the dominant oxidation product of NaDT) at low pH. The low pH requirement indicates that sulfur dioxide (SO2) is the species involved. Spectroscopy supports binding at or near [4Fe-4S]H, causing its redox potential to increase by ∼60 mV. This potential shift detunes the redox potentials of the subclusters of the H-cluster, lowering activity, as shown in protein film electrochemistry (PFE). Together, these results indicate that HoxH and its one-electron reduced counterpart Hred′H are artifacts of using a nonphysiological reductant, and not crucial catalytic intermediates. We propose renaming these states as the “dithionite (DT) inhibited” states Hox-DTi and Hred-DTi. The broader potential implications of using a nonphysiological reductant in spectroscopic and mechanistic studies of enzymes are highlighted.

Introduction

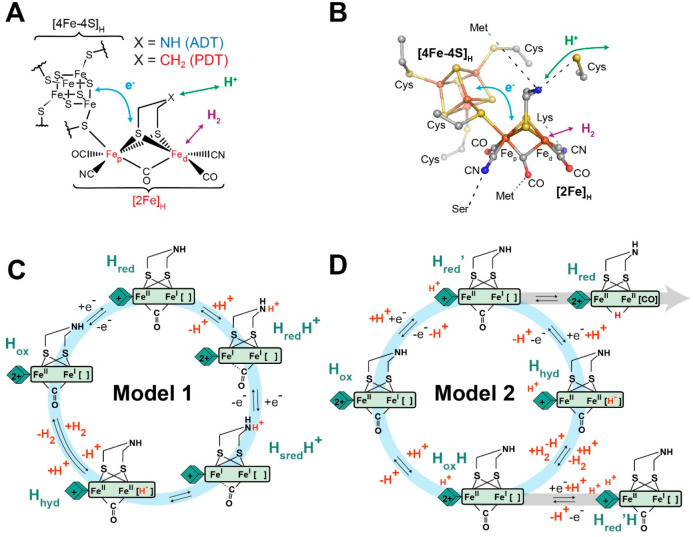

[FeFe] hydrogenases are highly active metalloenzymes that catalyze the reversible reduction of protons to molecular hydrogen.1,2 Their active site, the H-cluster, comprises a unique diiron subcluster ([2Fe]H) and a canonical [4Fe-4S] subcluster ([4Fe-4S]H), covalently linked by a cysteine thiolate3,4 (Figure 1 A and B). The Fe of [2Fe]H that is closest to [4Fe-4S]H is known as the proximal Fe (Fep), while the Fe furthest from the cluster is known as the distal Fe (Fed). In [2Fe]H, the Fe ions are coordinated by two terminal CN– and two terminal CO ligands (one on each Fe), a bridging CO, and a bridging 2-azapropane-1,3-dithiolate (ADT) ligand.5,6 During H2 conversion, the H-cluster goes through a series of redox transitions, where the Fe ions change oxidation states, as well as protonation/deprotonation steps.7−9 While several catalytic intermediate states have been well characterized with a variety of spectroscopic techniques, structural models based on X-ray diffraction data on crystals in spectroscopically defined states are not generally available. Thus, in the absence of structural models supported by experimental data, computational chemistry has played an important role in proposing likely structures of the active site in the catalytic intermediates based on spectroscopic data. However, divergent results from various groups have led to several possible models of the catalytic cycle of [FeFe] hydrogenases.8,10−12 These can be summarized in two main models (here referred to as Model 1 and 2, Figure 1C and D respectively).

Figure 1.

Structure of the H-cluster and proposed catalytic cycles. (A) Schematic showing the chemical structure of the [2Fe]H subcluster attached covalently to the [4Fe-4S]H subcluster. “X” in the bridgehead position is an NH group in the native ADT ligand and is CH2 in the synthetic chemical variant PDT. (B) Structure of [2Fe]H and [4Fe-4S]H from HydA1 from Clostridium pasteurianum (PDB: 4XDC(26)) showing the nearby amino acids that interact with [2Fe]H. (C) Catalytic cycle Model 1 in which one-electron reduction of [4Fe-4S]H is followed by proton-coupled electronic rearrangement to give the HredH+ state.14 A further one-electron reduction of [4Fe-4S]H gives the HsredH+ state,16 which is then followed by rearrangement to give the Hhyd state with a terminal hydride at Fed.19−21 The subsequent steps leading to H2 formation are not shown. (D) Catalytic cycle Model 2 in which proton-coupled electron transfer at [4Fe-4S]H converts Hox to Hred′, which can engage in further proton-coupled electron transfer to give the terminal hydride-containing Hhyd state.10,19 Hhyd then reacts with an additional proton to generate H2 leaving a protonated HoxH state.27 Alternatively, Hred′ can rearrange to give a less active Hred state containing a bridging hydride,28 which proceeds through a low activity pathway. HoxH appears to undergo one-electron reduction to Hred′H, but this is not included in the catalytic cycle.10,27

The most oxidized state of the active enzyme, Hox, is generally accepted to be the starting point of the catalytic cycle and has a mixed valence of Fep(II)Fed(I) in [2Fe]H,13 and an oxidized [4Fe-4S]H2+. In Model 1 (Figure 1C), one-electron reduction of Hox is proposed to yield two possible states Hred and HredH+ (in our nomenclature), whose relative population depends on the pH. In Hred, the electron is thought to be localized preferentially on [4Fe-4S]H. In HredH+, the electron is thought to be transferred to the [2Fe]H subcluster (with an Fep(I)Fed(I) configuration) and a proton (from the proton transfer pathway) to bind to the nitrogen in the ADT bridge giving an NH2+.14,15 This process of proton-coupled electronic rearrangement (PCER) of the H-cluster is a crucial component of Model 1. A further one-electron reduction of HredH+ yields the HsredH+ state with a reduced [4Fe-4S]H.16,17 The protonated ADT ligand in both HredH+ and HsredH+ appears to be able to transfer the proton to Fed generating an Fe-bound hydride in the Hhyd state.18−23 Finally, the Hhyd state is thought to gain an additional proton, which may trigger a similar PCER process as in the Hred state, and form a H2 molecule bound to Fed, which can then leave the enzyme via a hydrophobic gas channel.24 Recently, photoexcitation of HredH+ and HsredH+ was shown to generate two different forms of Hhyd, known as Hhyd:ox and Hhyd:red, where the former has an oxidized [4Fe-4S]H and the latter has a reduced [4Fe-4S]H.25

In Model 2 (Figure 1D),8 the Hred state (referred to as Hred′) is formed from Hox by proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) at [4Fe-4S]H. This was suggested based on IR spectroelectrochemical titrations at various pH values that showed a pH-dependent redox potential of [4Fe-4S]H.10 Specifically, the proton is thought to bind to one of the cysteine ligands coordinating the cluster. This state then undergoes an additional PCET at [2Fe]H to give the Hhyd state,19 and the proton is retained on [4Fe-4S]H. Hydrogen is then formed by additional protonation leaving an oxidized H-cluster but still protonated at [4Fe-4S]H, a state called HoxH.27 In Model 2, HredH+ (referred to as Hred) and HsredH+ (not shown in Figure 1D) contain a bridging hydride (μH–) and an apical CO ligand,28 and are considered to be part of a low activity pathway. Lastly, reduction of HoxH to Hred′H has also been observed,10 but its place in the catalytic cycle remains to be determined.

The HoxH and Hred′H states in Model 2 have been reported to accumulate at low pH only in the presence of sodium dithionite (NaDT) (see Supporting Information for further details).10,27 NaDT (Na2S2O4, also sodium hydrosulfite) is widely used in biochemistry as an oxygen scavenger and low potential reducing agent (E0’ = −0.66 V vs SHE at pH 7 and 25 °C).29 For example, it is commonly employed to protect metalloproteins from oxidative damage caused by trace amounts of oxygen during purification and handling, or to poise metallocofactors in reduced states for their characterization. However, one of the pitfalls of its use is the failure to consider that NaDT and its oxidation products can engage in side-reactions with the system under study. Several studies on sulfite-reducing enzymes have highlighted how oxidation of NaDT can be a significant source of SO32–, the substrate for these enzymes, which can bind to the active site and complicate the interpretation of spectroscopic studies and activity measurements.30−32 In a recent report, during the semisynthetic assembly of the FeMo cofactor of nitrogenase, the donor of the ninth sulfur ligand was found to be the SO32– generated by the oxidation or degradation of NaDT present in the assay.33 Numerous studies have reported the interaction of oxidation products of NaDT with various enzymes including nitrite reductase,34−36 DMSO reductase,37 monomethylamine methyltransferase,38 acetyl CoA synthase,39 and formation of adducts to flavins40−42 and cobalamin.43,44 Additionally, the slow dissociation of NaDT into SO2•– radicals (the active reducing species) has been shown to be problematic in mechanistic studies of nitrogenase.45

In light of the dependence of HoxH and Hred′H on NaDT, and of NaDT’s reported “non-innocent” behavior, we decided to investigate the effect of NaDT and its oxidation products on [FeFe] hydrogenases. Formation of the HoxH state was observed when the [FeFe] hydrogenase from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (CrHydA1) was treated with oxidized NaDT. Addition of Na2SO3 (the dominant oxidation product of NaDT46) to CrHydA1 at low pH reproduced the same effect as oxidized NaDT. Under H2, Hred′H was also observed. We propose that, at low pH, the dissolved sulfur dioxide (SO2) generated by the protonation of SO32– binds to the H-cluster. Based on our spectroscopic observations, we hypothesize that this occurs near [4Fe-4S]H with submicromolar binding affinity as estimated by IR titrations. Based on the ratios of the Hox/Hred and HoxH/Hred′H states under H2, binding of SO2 causes the redox potential of [4Fe-4S]H to increase by ∼60 mV. The effect of this on catalysis was investigated via protein film electrochemistry (PFE), showing that binding of SO2 has an inhibitory effect on both H+ reduction and H2 oxidation activity of [FeFe] hydrogenases. Together, these results reveal that the so-called HoxH and Hred′H states are not related to protonation events at the [4Fe-4S]H subcluster of the H-cluster, but are instead artifacts generated by oxidized NaDT. This result challenges their involvement in the catalytic cycle of [FeFe] hydrogenases. Furthermore, these findings highlight the importance of carefully considering the possible side-reactions of NaDT and its oxidation products when choosing to use this reducing agent with metalloenzymes, particularly iron–sulfur enzymes.

Results

Treatment of CrHydA1 with oxidized NaDT causes formation of the HoxH state

Our investigation on the effect of the oxidation products of NaDT on [FeFe] hydrogenases focused, in the first instance, on CrHydA1, the most well characterized [FeFe] hydrogenase, which contains only the H-cluster. In particular, the enzyme containing the native [2Fe] cofactor with the ADT ligand (CrHydA1ADT) was used. Thus, CrHydA1ADT produced in the strict absence of NaDT was treated with a solution of oxidized NaDT (oxNaDT). This solution was prepared by dissolving fresh NaDT in water to a concentration of 1 M (the most effective concentration of NaDT for HoxH formation at pH 627) under aerobic conditions and stirring for 2 h under atmospheric oxygen. A decrease in the pH to ∼2 and appearance of a yellow precipitate (most likely elemental sulfur) indicated oxidation and degradation of the dithionite anion.47 The oxNaDT solution was then thoroughly degassed and moved into an anaerobic glovebox before being added to CrHydA1ADT, in order to avoid damaging the highly air-sensitive H-cluster.

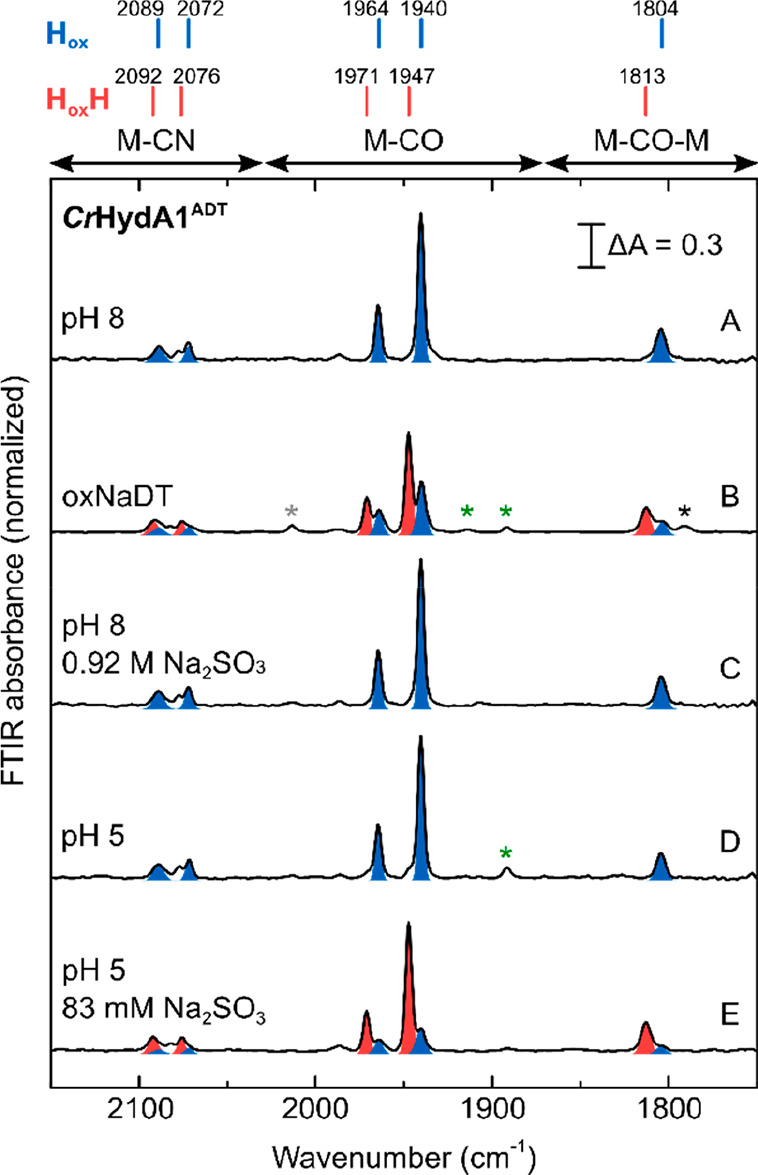

As shown by the IR spectra of CrHydA1ADT (Figure 2), dilution of the enzyme in the oxNaDT solution results in the appearance of a new set of vibrational signals, slightly shifted to higher energy (<10 cm–1) with respect to Hox. These new signals are consistent with those reported for HoxH.10,19,27 Even though the pH of the oxNaDT solution was measured to be around 2, the buffer present in the CrHydA1ADT sample (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8) will render the pH value after oxNaDT addition slightly higher than this (ca. pH 6). Interestingly, when CrHydA1ADT was treated with a solution oxNaDT whose pH had been corrected to 7, conversion to HoxH was not observed (Figure S1), suggesting that formation of this state requires acidic conditions.

Figure 2.

IR spectra of CrHydA1ADT showing formation of HoxH with oxNaDT and Na2SO3 at low pH. IR spectra of CrHydA1ADT were measured under a N2 atmosphere at room temperature in 20 mM mixed buffer (see experimental section) pH 8 (A), in 0.83 M acidic oxNaDT (B), 0.92 M Na2SO3 pH 8 (C), in 20 mM mixed buffer pH 5 in the absence (D), or the presence (E) of 83 mM Na2SO3. Spectra were normalized to allow easier comparison from different measurements. Peaks for the Hox and HoxH states are highlighted in blue and red, respectively. Small contributions from the Hox-CO (gray asterisk), HredH+ (green), and Hred (black) states are indicated. Importantly, Na2SO3 solutions were pH corrected before use, whereas the solution of oxNaDT was not pH corrected, but measured to be around 2.

The observation that HoxH can be formed by treatment with oxidized NaDT challenges the hypothesis that HoxH and Hred′H are protonated versions of the H-cluster. However, it was not clear which component of oxNaDT was interacting with the H-cluster. To better understand the nature of these two states and their role in the catalytic cycle of [FeFe] hydrogenases, we sought to identify the oxidation product(s) of NaDT responsible for their formation.

HoxH forms in the presence of sulfite at low pH

The main oxidation and degradation products of NaDT are sulfate (SO42–), thiosulfate (S2O32–), and sulfite (SO32–),48,49 all of which could potentially interact with the H-cluster of CrHydA1 and cause conversion to the HoxH state. Therefore, to identify the NaDT oxidation products responsible for this conversion, we tested these species individually on CrHydA1 at both pH 8 and pH 5. Treatment of CrHydA1 with Na2SO4 and Na2S2O3 at either pH 8 or pH 5 failed to reproduce the HoxH state (Figure S2). In contrast, we found that addition of 80 mM of Na2SO3 at pH 5 reproduced the effect of oxNaDT and caused almost full conversion to the HoxH state, while at pH 8 even a high concentration (0.92 M) of Na2SO3 had no effect on CrHydA1 (Figure 2). Importantly, CrHydA1 at pH 5 before addition of Na2SO3 has an identical spectrum to that at pH 8, demonstrating that both low pH and Na2SO3 are required for HoxH formation. Na2SO4, Na2S2O3, and Na2SO3 solutions were pH corrected before use—this is particularly important for Na2SO3, which is a mild base.

In addition to CrHydA1, also the bacterial [FeFe] hydrogenases HydAB from Desulfovibrio desulfuricans (DdHydAB) and HydA1 from Clostridium pasteurianum (CpHydA1) have been reported to form the HoxH state at low pH and in the presence of NaDT.27 These enzymes harbor additional [4Fe-4S] clusters (F-clusters) that form an electron-transfer chain from the protein surface to the H-cluster, and compared to CrHydA1, their active site is deeply buried inside the protein scaffold.3,4 When treated with Na2SO3 under acidic conditions, also DdHydAB and CpHydA1 converted to the HoxH state (Figure S3), indicating that the interaction of the H-cluster with the oxidation product of NaDT is a generalized phenomenon in [FeFe] hydrogenases.

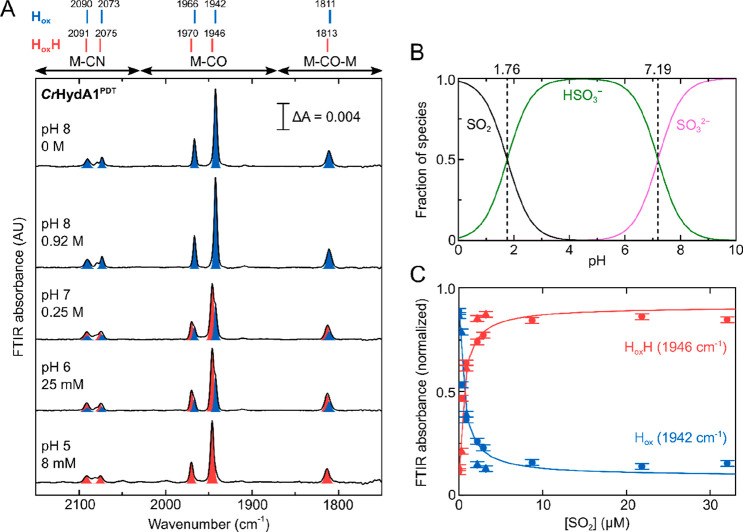

A protonated form of sulfite interacts with the H-cluster

Next, we decided to carry out titrations of CrHydA1 with Na2SO3 at various pH values in order to provide further details on the particular form of Na2SO3 that binds, as well as determining the binding affinity. In order to simplify the titrations, we chose to use a chemical variant of CrHydA1 with a [2Fe]H analogue containing a propane dithiolate (PDT) bridging ligand instead of ADT (CrHydA1PDT, Figure 1A). Compared to the amine in ADT, the methylene group in PDT cannot be easily protonated. As a result, CrHydA1PDT has very low catalytic activity and the H-cluster cannot assume states with a reduced [2Fe]H (i.e., HredH+ and HsredH+) (Figure 1C). This greatly reduces the number of states observable in the IR spectra, simplifying data analysis. The PDT-containing enzyme was previously shown to convert to HoxH and Hred′H at low pH in the presence of NaDT.10,27CrHydA1PDT was titrated with increasing amounts of Na2SO3 at five different pH values (Figure 3 and Figures S4–S6). In an anaerobic glovebox with a 100% N2 atmosphere, the H-cluster was in the oxidized state Hox at the beginning of the titration for all the pH values tested. As already observed for native CrHydA1ADT, at pH 8 addition of even a very high concentration of Na2SO3 did not affect the state of the H-cluster, which remained in the Hox state. Conversely, at pH 7, HoxH appeared already with less than 250 mM Na2SO3, and complete conversion was observed at around 700 mM. The concentration of Na2SO3 needed in order to observe complete conversion from Hox to HoxH decreased at pH 6 to about 200 mM and at pH 5 to less than 8 mM. At pH 4, 1 mM Na2SO3 gave essentially complete conversion to HoxH, while 1 mM Na2SO3 at pH 5 gave a roughly equal mixture of Hox and HoxH (Figure S5).

Figure 3.

Titration of CrHydA1PDT with Na2SO3 under N2 at various pH values. (A) IR spectra are shown for a range of conditions (pH 5–8) under various concentrations of Na2SO3 (0–0.92 M). The peaks for the Hox and HoxH states are highlighted in blue and red, respectively. (B) Predicted speciation of sulfite in water as a function of the pH assuming an acid dissociation constant (pKa) of 7.19 for HSO3– ⇌ H+ + SO32– and an equilibrium constant (pK) of 1.76 for SO2 + H2O ⇌ H+ + HSO3–.50 (C) Variation in the intensity of the 1942 cm–1 (Hox) and 1946 cm–1 (HoxH) peaks with the estimated concentration of dissolved SO2 at pH 7 (triangles) and 6 (circles). The data were fitted with a model describing binding of SO2 to the hydrogenase with 1:1 stoichiometry and assuming that the concentration of SO2 at equilibrium is determined only by the pH and the concentration of Na2SO3. The data at pH 6 and 7 were fitted simultaneously to the same model. For an expanded version of the region from 0 to 6 μM SO2; see Figure S6E. Error bars (±standard deviation) were determined by measuring the 0, 0.25, and 0.92 M Na2SO3 spectra at pH 7 and the 25 mM Na2SO3 spectrum at pH 6 in triplicate, which gave standard deviations of less than 0.014.

In aqueous solutions SO32– is in equilibrium with its protonated form bisulfite (HSO3–), which in turn can be further protonated to form sulfurous acid (H2SO3), which immediately decomposes to sulfur dioxide (SO2) and water (Figure 3B).51−53 As Figure 3 shows, the lower the pH, the lower the concentration of sulfite needed to convert Hox to HoxH. This, therefore, excludes that SO32–, whose abundance is predicted to greatly decrease when changing the pH from 8 to 6, is responsible for formation of HoxH. Since, as shown in Figure 3A, lowering the pH from 6 to 5, and then to 4 (Figure S5), caused a further reduction in the required concentration of Na2SO3 needed to convert Hox to HoxH, while the fraction of HSO3– should be constant in this range (Figure 3B), HSO3– is also unlikely to be the form of Na2SO3 binding to the H-cluster. In a pH titration of Na2SO3 monitored by IR spectroscopy we observed that the intensity of peaks relative to HSO3– indeed saturated after pH 6.0–5.5, while signals indicative of the presence of SO2 appeared at pH 5 (Figure S7). Therefore, we hypothesize that the species interacting with the H-cluster to form HoxH is SO2. This seems reasonable considering that SO2 is a neutral molecule able to easily diffuse through hydrophobic channels54,55 to reach the H-cluster from the protein surface, while the anions HSO3– and SO32– will be prevented from entering due to their charge and their large hydration spheres in aqueous solution.56 A similar suggestion was made to explain how S2– reaches the H-cluster as H2S to form the Hinact state.57

At pH 7 and 6, even at high concentration of sulfite, the concentration of dissolved SO2 is expected to be very low. Thus, in order to observe binding to the H-cluster and formation of HoxH, SO2 must have a tight affinity for the enzyme. Figure 3C shows the conversion from Hox to HoxH as a function of the estimated concentration of SO2 at each Na2SO3 addition, at either pH 6 or 7. The population of the two states was monitored from the intensity of the most prominent CO band at 1942 cm–1 for Hox and 1946 cm–1 for HoxH, in both cases corresponding to the stretch of the terminal CO on Fed. The titration curves at pH 7 and 6 as a function of the concentration of SO2 overlay nicely, in contrast to those obtained using the estimated concentrations of HSO3– and SO32– (Figure S6). Fitting the data in Figure 3C to a simple equilibrium model describing one SO2 molecule binding to the hydrogenase (SO2 + E ⇌ E:SO2) gave an estimated binding affinity of ∼500 nM. In our analysis, we considered that the pool of Na2SO3 can act as a buffer system for SO2, replenishing what is consumed to form the enzyme:SO2 complex (E:SO2). For all the data points, the concentration of E:SO2 formed was negligible compared to the total concentration of Na2SO3, so that the concentration of SO2 at equilibrium could be assumed to be independent of the formation of E:SO2 and to be determined only by the pH and the total concentration of Na2SO3, an important consideration for such tight binding interactions. To put this in context, CO has been estimated to bind with 100 nM affinity to CrHydA1ADT.58

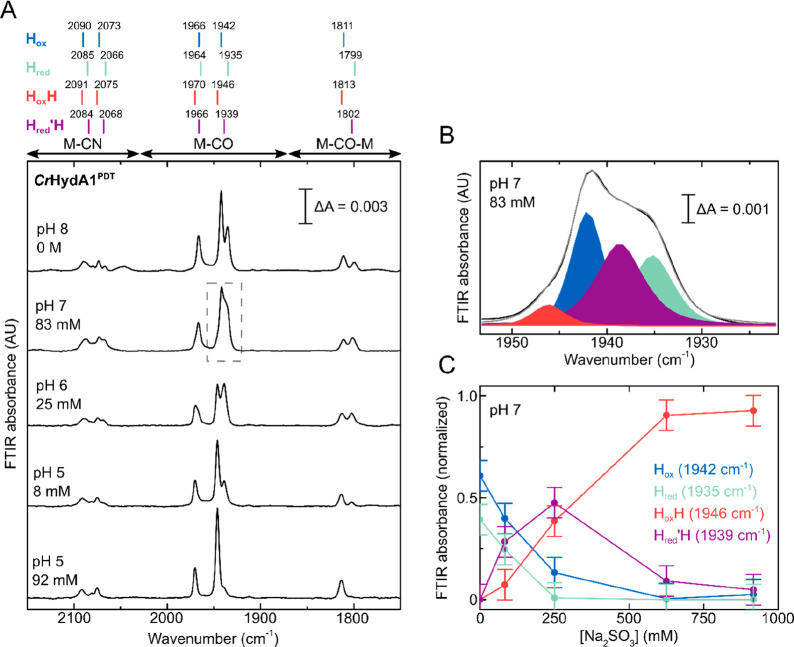

Addition of sulfite under reducing conditions (H2 atmosphere) forms Hred′H

The titration of CrHydA1PDT with sulfite was repeated in the presence of 2% H2 in the atmosphere of the anaerobic glovebox (Figure 4). Under these conditions, slow reactivity of the CrHydA1PDT enzyme with H2 can lead to reduction of the [4Fe-4S]H subcluster, in particular at high pH values. This is due to the potential of the 2H+/H2 couple, which becomes more positive as the pH decreases, while the redox potential of [4Fe-4S]H is pH independent.12 At pH 7, after addition of a small amount of Na2SO3, we observed a mixture of the Hox, Hred, and HoxH states in the IR spectra, plus a new set of signals. These are consistent with the vibrational frequencies of the Hred′H state, which Stripp and co-workers reported to form with NaDT at low pH and either under H2 or at low electrochemical potential.10,27 Similar to what was observed under N2, at lower pH the formation of HoxH and Hred′H was observed at lower concentration of Na2SO3. In order to estimate the proportion of each state present under each condition, we performed a pseudo-Voigt peak-fitting analysis of the region of the spectrum between ∼1955 cm–1 and ∼1920 cm–1, containing the most dominant bands for Hox (1942 cm–1, blue), Hred (1935 cm–1, cyan), HoxH (1946 cm–1, red), and Hred′H (1939 cm–1, purple) (Figures 4B, S8–S10). In Figure 4C, the intensity of these contributions is plotted as a function of the concentration of Na2SO3 at pH 7. At low Na2SO3, both the HoxH and Hred′H states are observed, but at high concentrations of Na2SO3 Hred′H is converted to HoxH. This indicates oxidation of the [4Fe-4S]H subcluster by Na2SO3. Since the samples were prepared in a closed IR cell and the concentrations of sulfite used are much higher than the dissolved concentration of H2, oxidation by Na2SO3 will slowly deplete the H2 concentration leading to oxidation of the sample. Similar behavior is observed also at pH 6 and 5 (Figures S8, S10).

Figure 4.

Titration of CrHydA1PDT with Na2SO3 at various pH values under 2% H2. (A) IR spectra are shown for a range of conditions (pH 5–8) under various concentrations of Na2SO3 (0–0.92 M). (B) Peak-fitting to pseudo-Voigt functions of the region between 1955 and 1920 cm–1 for the data in the dashed rectangle in A. Color code: Hox blue, Hred cyan, HoxH red, Hred′H purple. (C) The variation in the intensity of the 1942 cm–1 (Hox), 1935 cm–1 (Hred), 1946 cm–1 (HoxH), and 1939 cm–1 (Hred′H) peaks with the Na2SO3 concentration at pH 7. The lines connecting the points in C are for visual purposes only. Error bars (±standard deviation) were determined by measuring the 0, 0.25, and 0.92 M Na2SO3 spectra at pH 7 in triplicate, which gave standard deviations of less than 0.075.

At low concentrations (8 mM) of Na2SO3, at pH 6, the Hred′H is the most dominant state, while HoxH becomes more favored at pH 5 at the same concentration of Na2SO3, agreeing with a pH independent redox potential of [4Fe-4S]H also when SO2 is bound. However, the fact that SO2 is more prevalent at low pH gives the conversion of Hox/Hred to HoxH/Hred′H an “apparent” pH dependence. This will complicate the interpretation of pH-dependent redox titrations performed in the presence of oxidation products of sodium dithionite (including Na2SO3 and SO2), which may explain discrepancies in the literature.10,12

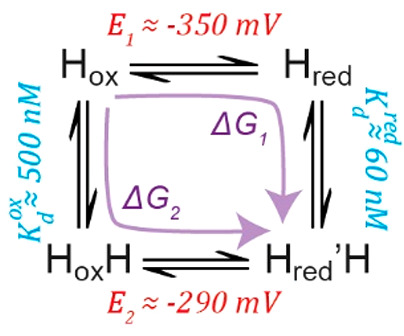

Interestingly, at low concentrations of Na2SO3, the ratio of Hox:Hred is much greater than that of HoxH:Hred′H, suggesting that binding of SO2 increases the redox potential of the [4Fe-4S]H subcluster (Figure 4B and S8, S9). The redox potential for the Hox/Hred and HoxH/Hred′H transitions can be calculated at pH 6 and 7 at low concentrations of Na2SO3 from the populations of the four states (Figure S11). Using the Nernst equation, we found that Em (Hox/Hred) = −349 (±17) mV and Em (HoxH/Hred′H) = −293 (±26) mV. The value for Em (Hox/Hred) is in close agreement with that determined previously.12,59 The fact that the redox potential for the HoxH/Hred′H transition is ∼60 mV more positive than the Hox/Hred transition also indicates a tighter binding affinity for SO2 to the Hred state than to the Hox state. We determined a Kd for SO2 binding to the Hox state of ∼500 nM from the titrations in the absence of H2. By considering the thermodynamic cycle (Scheme 1) connecting the Hox, Hred, HoxH, and Hred′H states, it can be calculated that an ∼60 mV difference in the redox potentials indicates a Kd of ∼60 nM for SO2 binding to the Hred state, approximately 1 order of magnitude tighter. This also means that low concentrations of Na2SO3 have a larger effect in the presence of H2 (compare Figure 4B with Figure S4B).

Scheme 1. Thermodynamic Cycle Connecting Hox, Hred, HoxH, and Hred′H.

One-electron reduction of Hox and HoxH gives Hred and Hred′H, respectively, with redox potentials of E1 ≈ −350 mV and E2 ≈ −290 mV, respectively. Hox and Hred convert to HoxH and Hred′H, respectively, by binding SO2. The Kd for SO2 binding to the Hox state was measured to be ∼500 nM. By consideration of the fact that the Gibbs free energy is a state function, the ΔG associated with the transition from Hox to Hred′H is the same regardless of whether we go via Hred (ΔG1) or via HoxH (ΔG2), allowing us to calculate the Kd for binding of SO2 to the Hred state to be ∼60 nM.

The site of SO2 binding is not the open coordination site on [2Fe]H

From the previous section, it is clear that SO2 somehow interacts with the H-cluster of [FeFe] hydrogenases. It is tempting to speculate that SO2 diffuses through the hydrophobic gas channel leading to the open coordination site on Fed. However, we cannot exclude that SO2 binds elsewhere, and indeed, the change in the redox potential of [4Fe-4S]H would suggest that binding near to [4Fe-4S]H is more likely. To test whether binding of SO2 with the H-cluster occurs at the open coordination site on [2Fe]H, we investigated how its presence can affect the interaction of the enzyme with CO, a competitive inhibitor of [FeFe] hydrogenases that binds to Fed.60 At pH 5 exposure of CrHydA1ADT to 100% CO gas for 10 min in the absence of Na2SO3 generates pure Hox-CO (Figure S12). In the presence of a high concentration of sulfite at pH 5, exposure of CrHydA1 to CO caused the appearance of new peaks that correspond to neither Hox-CO nor HoxH, and are similar to the HoxH–CO state described by Stripp and co-workers (Figure S12).27 This suggests that SO2 does not compete for the same binding site as CO, which is the open coordination site at Fed.

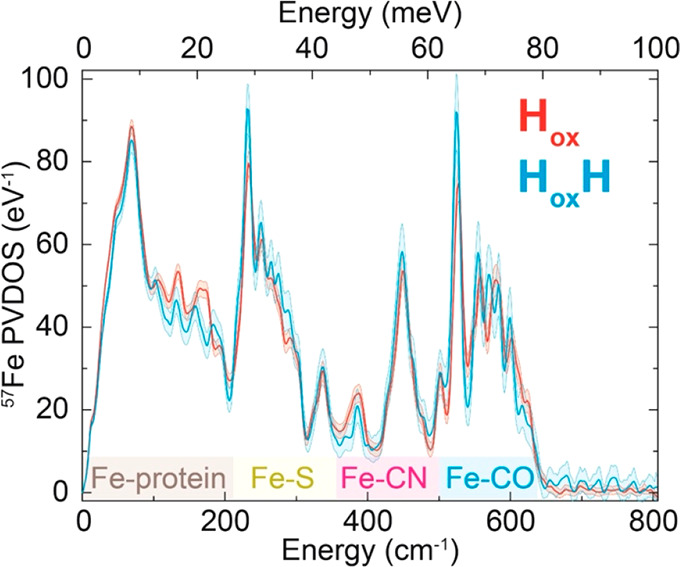

In order to get further information on the SO2 binding site, we measured 57Fe nuclear resonance vibrational spectroscopy (NRVS). This technique measures Fe-ligand vibrational energies using nuclear excitation of 57Fe and has been used extensively to probe ligand binding to the [2Fe]H subcluster in [FeFe] hydrogenase.21−23,28,57 We artificially maturated apo-CrHydA1 samples with a 57Fe-labeled diiron subcluster precursor ([257Fe]ADT) and measured NRVS in the Hox and HoxH states (Figure 5). This enzyme is labeled with 57Fe in the [2Fe]H subcluster and not in the [4Fe-4S]H subcluster, so only vibrations involving motion of the [2Fe]H subcluster can be observed. The spectra of Hox and HoxH are very similar but with small shifts of the peaks to lower energy for the HoxH, indicative of decreased electron density on the [2Fe]H subcluster, similar to results observed by Mebs et al.(28) In contrast, ligand binding to Fed on the [2Fe]H subcluster would be expected to have much more dramatic changes, particularly, the generation of additional Fe–S or Fe–O vibrations.57,61 The results cannot definitively confirm the [4Fe-4S]H subcluster as the point of SO2 binding, but together with the observation of the HoxH–CO state, they do exclude the open coordination site on Fed as the SO2 binding site.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the NRVS spectra of CrHydA1 maturated with an 57Fe-labeled [2Fe]ADT precursor complex in the Hox (red) and HoxH (blue) states measured at 10 K. The regions of the spectra corresponding to Fe-protein, Fe–S, Fe-CN, and Fe-CO vibrations are highlighted in brown, yellow, pink, and blue along the x-axis.

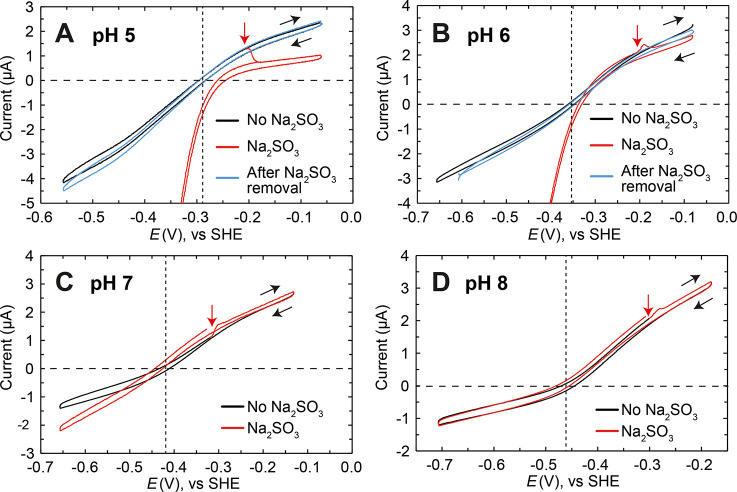

SO2 inhibits catalysis by [FeFe] hydrogenase

In order to investigate the effect of SO2-binding to the H-cluster on catalysis, we performed protein film electrochemistry on the DdHydAB enzyme covalently attached to a pyrolytic graphite electrode. We chose DdHydAB rather than CrHydA1, as the former is, in our hands, much easier to covalently attach to graphite electrode surfaces.62 As shown in the cyclic voltammograms (CVs) in Figure 6 and in the enlarged version of the CVs reported in Figure S13, a large negative current at low potentials is observed when Na2SO3 is injected into the electrochemical cell under acidic conditions (pH 5 and pH 6, respectively A and B in Figure 6). Controls experiments (bare graphite electrode injecting Na2SO3, Figure S14) suggest that this reduction current is likely due to HSO3– and SO2 being reduced by the pyrolytic graphite electrode.63 Comparisons of bare graphite electrodes and DdHydAB-modified electrodes at various pH values are presented in the absence (Figure S15) and presence (Figure S16) of Na2SO3. Unfortunately, this massive reduction current masks the effect of Na2SO3 on the catalytic H+-reduction current.

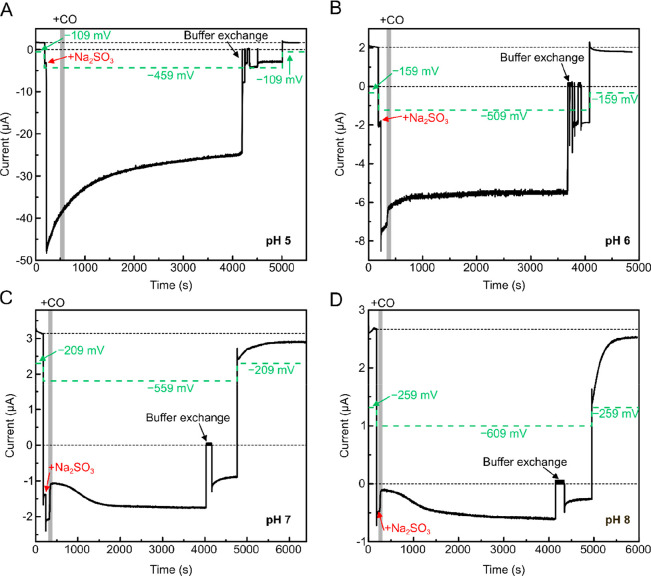

Figure 6.

Protein film electrochemistry of DdHydAB in the presence of sulfite. DdHydAB was covalently attached to a pyrolytic graphite electrode and cyclic voltammetry (CV) was performed in 20 mM mixed buffer with 100 mM NaCl at pH 5 (A) 6 (B), 7 (C), and 8 (D) under 100% H2 (1000 mL/min), at 25 °C, with 2000 rpm rotation, and a scan rate of 0.02 V/s. After 3 CVs in the absence of Na2SO3 (only the third trace is shown, black trace), 40 mM Na2SO3 was added (red trace). Only a single CV before and after the addition of Na2SO3 are shown. However, consecutive CVs showed the same shape. After replacing the buffer in the electrochemical cell with Na2SO3-free buffer, DdHydAB recovered its original activity (blue traces). The red arrow indicates the point of Na2SO3 injection. The black arrows indicate the scan direction of the CV. The dashed horizontal line shows the zero current position, and the dashed vertical line shows the equilibrium 2H+/H2 potential at each pH value. Enlarged versions of A and B are reported in Figure S13.

However, as shown in Figure 6A and B (CV at pH 5 and 6 in the presence of Na2SO3, respectively), in the presence of Na2SO3 the catalytic H2-oxidation current decreases, suggesting inhibition of the enzyme as a result of the H-cluster somehow interacting with SO2. The inhibitory effect on the catalytic H2-oxidation current is more pronounced at lower pH (the CVs at pH 7 and 8 are reported in Figure 6C and D, respectively), in agreement with the pH-dependent formation of HoxH and Hred′H observed in the IR measurements. To explore whether the inhibition is reversible and the electrocatalytic H2-oxidation current can be recovered, the buffer in the electrochemical cell was exchanged to a fresh buffer without Na2SO3 during the course of the CVs. Sulfite-exposed DdHydAB recovered 100% of the electrocatalytic H2-oxidation current once Na2SO3 was removed from the electrochemical cell, suggesting that SO2 binding and inhibition are fully reversible (blue trace in Figure 6A and B) and that the enzyme is not irreversibly damaged by SO2.

The massive current at low potential due to direct reduction of HSO3– and SO2 species by the electrode makes it difficult to assess the effect of Na2SO3 on the electrocatalytic H+-reduction current. To distinguish the enzymatic contribution from the direct HSO3– and SO2 reduction by the electrode, we performed chronoamperometry experiments (the applied potential is held at a specific value while the current is monitored vs time) in the presence and absence of CO (Figure 7). As previously described,58,62 the current decrease due to CO addition (as CO binds to open coordination site on Fed and inhibits the enzyme) provides a direct measurement of the enzymatic H+ reduction. In the experiment in Figure 7A, performed at pH 5, DdHydAB attached on the pyrolytic graphite electrode was initially exposed to 90% H2/10% N2 at −109 mV vs SHE, where a positive current due to H2 oxidation was observed (as the applied potential is more positive than the thermodynamic potential of the 2H+/H2 couple at this pH, −295 mV vs SHE). Switching to −459 mV gave a small negative current due to H+ reduction (as the applied potential is now more negative than E2H+/H2 at this pH). Adding Na2SO3 at this potential gave an extremely large negative current, which was unaffected by addition of 10% CO into the gas feed (replacing the 10% N2). This indicates that the large negative current is entirely due to Na2SO3 reduction and that catalytic H+ reduction by DdHydAB is completely inhibited under these conditions. Replacing the buffer with fresh Na2SO3-free buffer decreased the current to the original value observed before addition of Na2SO3. An analogous experiment at pH 6 (Figure 7B) showed a small decrease in the current after addition of CO, as well as experiments at pH 7 and pH 8 (Figure 7C and 7D, respectively), suggesting that at these pH values there is some contribution from the enzymatic H+ reduction current, in agreement with the pH dependent formation of SO2 from Na2SO3. Control experiments in the complete absence of Na2SO3 showed full inhibition of the electrocatalytic H+-reduction current by CO, thus demonstrating that in the absence of Na2SO3 the reductive current is indeed enzymatic H+ reduction (Figure S17). At this stage, it is unclear whether the loss in activity in both directions due to Na2SO3 addition is directly related to the increase in the redox potential of [4Fe-4S]H. The higher redox potential of the cluster may disrupt the proton-coupled electronic rearrangement between [4Fe-4S]H and [2Fe]H.14 These experiments help to understand the discrepancy between reported H+ reduction activity solution assays and electrochemistry. While solution assays (where NaDT is used as electron source) indicate a maximum in activity at pH 7,8 and almost no activity at pH 5, electrochemical measurements show the highest H+ reduction activity at pH 5 (Figure S15). Regardless, these data show that, under the conditions where HoxH and Hred′H form, the enzyme has lower activity, suggesting that these states are not active intermediates of the catalytic cycle of [FeFe] hydrogenases. This is in stark contrast to the suggestion from Stripp and Haumann that a catalytic cycle involving HoxH is actually the faster branch of the cycle compared to that involving the HredH+ and HsredH+ states (Figure 1D).

Figure 7.

Chronoamperometry experiments of DdHydAB in the presence of Na2SO3 and CO. Chronoamperometry experiments were performed on DdHydAB covalently attached to a pyrolytic graphite electrode under 1 bar 90% H2 in N2 (1000 mL/min), in 20 mM mixed buffer with 100 mM NaCl at pH 5 (A), pH 6 (B), pH 7 (C), pH 8 (D) at 25 °C and 2000 rpm rotation rate. During the experiment the potential was sequentially stepped as indicated by the green profile (all potentials are reported vs SHE). For example, at pH 5 (A) the potential was initially set to −109 mV, next stepped down to −459 mV, and finally back to the initial potential −109 mV. Addition of 40 mM Na2SO3 is indicated by red arrows, while addition of 10% CO (in 90% H2) to the gas mixture is indicated by the shaded gray area. After more than 3600 s, the buffer inside the electrochemical cell was rinsed and exchanged with fresh buffer without Na2SO3. Note the complex behavior in the region immediately following CO treatment at pH 6 in (B). This represents a convolution of the current recovery due to CO release and the exponential decay of the current as a result of decreasing Na2SO3 reduction. To observe the current recovery due to CO release, a simulated exponential decay curve was subtracted from the experimental data (Figure S17C), and the resulting difference curve is plotted in Figure S17D.

Discussion

In this work we have shown that in CrHydA1 the HoxH state forms in the presence of oxidation products of NaDT at low pH, specifically SO2. SO2 binding caused formation of HoxH not only with CrHydA1 but also with the bacterial enzymes CpHydA1 and DdHydAB, suggesting this is a common behavior in [FeFe] hydrogenases. Additionally, we have shown that with Na2SO3 and in the presence of H2 the reduced Hred′H state can also form. The electrochemistry measurements showed loss in electrocatalytic activity when DdHydAB was exposed to Na2SO3, especially at low pH, suggesting that HoxH and Hred′H are less active states and challenging their inclusion in the catalytic cycle. Taken together, these findings suggest that HoxH and Hred′H are not protonated versions of Hox and Hred, but instead are forms of Hox and Hred in which a product of NaDT oxidation, most likely SO2, is bound. Thus, we suggest renaming Hox-DTi and Hred-DTI (for dithionite inhibited) to avoid confusion, and for the rest of the discussion we will name them as such.

This result helps explain previous findings in the literature regarding these states. Originally, Hox-DTi and Hred-DTi were discovered during NaDT-mediated H+ reduction by [FeFe] hydrogenase at low pH.19,27 Under these conditions H+ reduction rates are high, leading to rapid oxidation of NaDT to generate a mixture of SO32–, HSO3–, and SO2. At low pH, SO2 forms due to the protonation equilibria and it can bind to the hydrogenase yielding the Hox-DTi and Hred-DTi states. It was noticed that the accumulation of Hox-DTi was dependent both on pH and on NaDT concentration, both of which will affect the rate of SO2 accumulation. Furthermore, it was noted that less active forms of the hydrogenase (e.g., with the PDT cofactor) accumulated Hox-DTi more slowly. In this case, the accumulation of SO2 depends on the rate of NaDT oxidation by the catalytic activity of the hydrogenase, and it is well established that the PDT-form of the hydrogenase is catalytically much less active than the native ADT-form.64

Protonation at [4Fe-4S]H is a critical component in the catalytic cycle proposed in Model 2 (Figure 1D). We recently demonstrated that (in the absence of NaDT) the redox potential of [4Fe-4S]H is pH-independent, challenging the involvement of PCET in the formation of Hred and the protonation at [4Fe-4S]H.12 Our current work further challenges protonation at [4Fe-4S]H by showing that the Model 2 key intermediate Hox-DTi (HoxH in Figure 1D) is generated by the oxidation products of NaDT. If reduction of [4Fe-4S]H is coupled to protonation then it has to be coupled to protonation in all the steps involving reduction of [4Fe-4S]H. Considering that the hydrogenase enzyme is reversible, with a very low overpotential in either direction, it must be assumed that each step in the catalytic cycle is also reversible and, thus, Hox should be able to protonate to give Hox-DTi. However, incubation of Hox at low pH in the absence of NaDT does not generate Hox-DTi (Figure 2), so Hox-DTi is clearly not a reversibly protonated form of Hox.

Our results also help to explain the misassignment of the pH dependence of the Hox/Hred transition. It is important to recall that in this study we also observe that the Hox-DTi/Hred-DTi transition is about 60 mV more positive than the Hox/Hred transition, as also reported by Senger et al.10 If the conversion of Hox to Hox-DTi and Hred to Hred-DTi depend on the pH, then we expect that the “apparent” redox potential of both transitions will shift from the intrinsic redox potential of Hox/Hred to the intrinsic redox potential of Hox-DTi/Hred-DTi as the pH is decreased. This is simply a consequence of the redox and protonation equilibria being coupled (see Supporting Information and Figure S18 for further details and a model illustrating this behavior). As we demonstrated that the SO2 concentration in solution increases with decreasing pH and that SO2 is responsible for binding to Hox/Hred to generate Hox-DTi/Hred-DTi, then this gives us a pH dependent conversion of Hox/Hred to Hox-DTi/Hred-DTi and, therefore, an apparent pH dependence of the redox potential.

A further important finding regarding the [FeFe] hydrogenase is the fact that SO2 appears to inhibit the H2 oxidation and H+ reduction activity of the enzyme. This may be due to the increased redox potential of [4Fe-4S]H. While we do not yet completely understand this effect, it highlights the importance of the balance of redox potentials between the two parts of the H-cluster in facilitating electronic coupling and efficient catalysis. We previously showed that mutation of a cysteine ligating [4Fe-4S]H to histidine increased the redox potential by ∼200 mV. This completely abolished H+ reduction activity, while actually enhancing H2 oxidation at high overpotentials.65

The now well-characterized Hhyd intermediate can be generated under conditions of high NaDT at low pH. It is not clear yet whether this state is also somehow influenced by the presence of SO2. However, it has always been intriguing how such an intermediate could be so stable by simply generating it at low pH in the presence of NaDT. Previous explanations have employed Le Chatelier’s principle and the concept of proton pressure.19 It may indeed be the case that SO2 binding stabilizes the Hhyd state by increasing the redox potential of the [4Fe-4S]H subcluster slowing electron transfer to [2Fe]H to generate H2. Recent evidence shows that versions of Hhyd can be generated from HredH+ and HsredH+.25 The so-called Hhyd:red state is generated from HsredH+ and should have a reduced [4Fe-4S]H subcluster analogous to Hhyd. Interestingly, the IR bands of Hhyd are shifted to higher energy compared with Hhyd:red by a similar amount to Hox-DTivs Hox (Table S2). Careful revaluation of the Hhyd state generated with NaDT at low pH is clearly necessary.

In addition to shedding light on the catalytic cycle of [FeFe] hydrogenases, this work reports how NaDT, a compound commonly employed as a reducing agent in metalloenzyme research, is responsible for the generation of artifacts, which were erroneously characterized as catalytically relevant states. To our knowledge, this is the first report of such “non-innocent” behavior of NaDT with [FeFe] hydrogenases, in this case caused by the interaction of one of the NaDT oxidation products with the enzyme. The experimental conditions should, thus, be carefully evaluated when NaDT is chosen as the reducing agent with these enzymes. As we have shown, acidic conditions facilitate formation of Hox-DTi, but at a high concentration of sulfite this state also forms at pH 7. Therefore, particular care must be taken when [FeFe] hydrogenase samples that contain (or contained) NaDT are studied at low pH, or in those cases where NaDT is used as a continuous source of electrons. While this is the first time that NaDT has been shown to interfere with spectroscopic studies of [FeFe] hydrogenases, several previous studies of various other metalloenzymes have reported similar effects. This problematic behavior has been attributed to several factors, from the slow kinetics of NaDT dissociation limiting the catalytic behavior to the unwanted interaction of its oxidation products with the system under study, as we described for [FeFe] hydrogenases. Importantly, the enzymes affected catalyze various reactions and harbor various metallocofactors, suggesting that it is difficult to predict which enzymes will be affected. As such, it is possible that similar effects are still going undetected for other systems. Therefore, the chemistry of NaDT and of its oxidation products should be carefully considered when choosing this compound as a reducing agent for metalloproteins research, and important control experiments should be routinely employed to identify possible side-reactions that can engage with the system under study. In the future it will also be important to evaluate alternative artificial reductants such as Ti(III) citrate (E0′ < −800 mV vs SHE66) and Eu(II)-DPTA (E0′ < −1 V vs SHE67) or the physiological redox partners for their use in hydrogenase research as well as with other metalloproteins.

Inhibition of [FeFe] hydrogenases by sulfite may not simply be an artifact but could represent a physiological mechanism for diverting electrons away from H+ reduction by hydrogenase and toward sulfite reduction by dissimilatory and assimilatory sulfite reductases. Here, we showed that the [FeFe] hydrogenases from C. reinhardtii, D. desulfuricans, and C. pasteurianum all form the HoxH state in the presence of sulfite, each of which contains a sulfite reductase. In C. reinhardtii and C. pasteurianum, both [FeFe] hydrogenase and sulfite reductase receive electrons from ferredoxin.68−70 Inhibition of the hydrogenase by sulfite would divert electrons from H+ reduction to sulfite reduction. In D. desulfuricans, [FeFe] hydrogenase supplies electrons for sulfite reduction via a membrane bound electron transport chain,71 and so inhibition of H2 oxidation could stop electron transfer to the sulfite reductase, increasing sulfite concentrations even further. However, under conditions of high H2S, the sulfite reductase is reversed, producing sulfite from H2S, leading to reverse electron transport and H+ reduction by [FeFe] hydrogenase. Inhibition of H+ reduction by sulfite would prevent this H2S oxidation and stop sulfite accumulation.

Conclusions

In this work we have shown that SO2, an oxidation product of the commonly used nonphysiological reductant sodium dithionite, binds tightly to [FeFe] hydrogenase converting the catalytic intermediate states Hox and Hred into the Hox-DTi and Hred-DTi states (previously named HoxH and HredH). Thus, our results do not support the notion of protonation of the [4Fe-4S]H subcluster of the H-cluster, nor that the Hox-DTi state is a critical intermediate in the catalytic cycle. SO2 most likely binds at or near the [4Fe-4S] subcluster and appears to increase the cluster redox potential. This in turn may explain the observed decrease in catalytic activity. Overall, these results highlight the importance of finely tuned redox potentials for catalytic activity and reversibility. More generally, these results should come as a cautionary note to all who use sodium dithionite in metalloprotein studies without concern for its “non-innocent” effects. Sodium dithionite is routinely used in studies on a wide range of metalloenzymes including nitrogenase, CO dehydrogenase, formate dehydrogenase, and many more. Careful evaluation of results from a range of nonphysiological reductants should help to establish the effects that are artifacts from those that represent the physiological behavior of the enzyme of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Inge Heise and Tabea Mussfeld, for synthesizing the unlabeled diiron cofactors, and Prof. Tom Rauchfuss, for supplying the 57Fe-labelled diiron cofactor. We acknowledge DESY (Hamburg, Germany), a member of the Helmholtz Association HGF, for the provision of experimental facilities. Parts of this research were carried out at PETRA-III, and we would like to thank Prof. Hans-Christian Wille, Dr. Ilya Sergeev, Dr. Olaf Leupold, and Dr. Atefeh Jafari for assistance in using P01. Beamtime was allocated for proposal I-20200085.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.1c07322.

Experimental section, supplementary figures and tables, supplementary discussion (PDF)

Open access funded by Max Planck Society. All the authors would like to thank the Max Planck Society for funding. J.A.B., M.A.M., and S.D. also acknowledge the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) Priority Programme “Iron–Sulfur for Life: Cooperative Function of Iron–Sulfur Centers in Assembly, Biosynthesis, Catalysis and Disease” (SPP 1927) Projects BI 2198/1-1 (J.A.B. and M.A.M.) and DE 1877/1-2 (S.D.). P.R.-M. is supported financially by the European Research Council (ERC-2018-CoG BiocatSus-Chem 819580, to K.A. Vincent), and acknowledges Linacre College Oxford for her Junior Research Fellowship.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Lubitz W.; Ogata H.; Rüdiger O.; Reijerse E. Hydrogenases. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114 (8), 4081–148. 10.1021/cr4005814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Land H.; Senger M.; Berggren G.; Stripp S. T. Current state of [FeFe]-hydrogenase research: biodiversity and spectroscopic investigations. ACS Catal. 2020, 10 (13), 7069–7086. 10.1021/acscatal.0c01614. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J. W.; Lanzilotta W. N.; Lemon B. J.; Seefeldt L. C. X-ray crystal structure of the Fe-only hydrogenase (CpI) from Clostridium pasteurianum to 1.8 angstrom resolution. Science 1998, 282 (5395), 1853. 10.1126/science.282.5395.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolet Y.; Piras C.; Legrand P.; Hatchikian C. E.; Fontecilla-Camps J. C. Desulfovibrio desulfuricans iron hydrogenase: the structure shows unusual coordination to an active site Fe binuclear center. Structure 1999, 7 (1), 13–23. 10.1016/S0969-2126(99)80005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silakov A.; Wenk B.; Reijerse E.; Lubitz W. 14N HYSCORE investigation of the H-cluster of [FeFe] hydrogenase: evidence for a nitrogen in the dithiol bridge. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2009, 11 (31), 6592–6599. 10.1039/b905841a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berggren G.; Adamska A.; Lambertz C.; Simmons T. R.; Esselborn J.; Atta M.; Gambarelli S.; Mouesca J. M.; Reijerse E.; Lubitz W.; Happe T.; Artero V.; Fontecave M. Biomimetic assembly and activation of [FeFe]-hydrogenases. Nature 2013, 499 (7456), 66–69. 10.1038/nature12239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roseboom W.; De Lacey A. L.; Fernandez V. M.; Hatchikian E. C.; Albracht S. P. J. The active site of the [FeFe]-hydrogenase from Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. II. Redox properties, light sensitivity and CO-ligand exchange as observed by infrared spectroscopy. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 11 (1), 102–118. 10.1007/s00775-005-0040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haumann M.; Stripp S. T. The molecular proceedings of biological hydrogen turnover. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51 (8), 1755–1763. 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez M. L. K.; Sommer C.; Reijerse E.; Birrell J. A.; Lubitz W.; Dyer R. B. Investigating the kinetic competency of CrHydA1 [FeFe] hydrogenase intermediate states via time-resolved infrared spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (40), 16064–16070. 10.1021/jacs.9b08348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senger M.; Laun K.; Wittkamp F.; Duan J.; Haumann M.; Happe T.; Winkler M.; Apfel U. P.; Stripp S. T. Proton-coupled reduction of the catalytic [4Fe-4S] cluster in [FeFe]-hydrogenases. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56 (52), 16503–16506. 10.1002/anie.201709910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratzloff M. W.; Artz J. H.; Mulder D. W.; Collins R. T.; Furtak T. E.; King P. W. CO-bridged H-cluster intermediates in the catalytic mechanism of [FeFe]-hydrogenase CaI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (24), 7623–7628. 10.1021/jacs.8b03072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Maciá P.; Breuer N.; DeBeer S.; Birrell J. A. Insight into the redox behavior of the [4Fe-4S] subcluster in [FeFe] hydrogenases. ACS Catal. 2020, 10 (21), 13084–13095. 10.1021/acscatal.0c02771. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reijerse E. J.; Pelmenschikov V.; Birrell J. A.; Richers C. P.; Kaupp M.; Rauchfuss T. B.; Cramer S. P.; Lubitz W. Asymmetry in the ligand coordination sphere of the [FeFe] hydrogenase active site is reflected in the magnetic spin interactions of the aza-propanedithiolate ligand. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10 (21), 6794–6799. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.9b02354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer C.; Adamska-Venkatesh A.; Pawlak K.; Birrell J. A.; Rüdiger O.; Reijerse E. J.; Lubitz W. Proton coupled electronic rearrangement within the H-cluster as an essential step in the catalytic cycle of [FeFe] hydrogenases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (4), 1440–1443. 10.1021/jacs.6b12636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S.; Noth J.; Horch M.; Shafaat H. S.; Happe T.; Hildebrandt P.; Zebger I. Vibrational spectroscopy reveals the initial steps of biological hydrogen evolution. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7 (11), 6746–6752. 10.1039/C6SC01098A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamska A.; Silakov A.; Lambertz C.; Rüdiger O.; Happe T.; Reijerse E.; Lubitz W. Identification and characterization of the “super-reduced” state of the H-cluster in [FeFe] hydrogenase: a new building block for the catalytic cycle?. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51 (46), 11458–11462. 10.1002/anie.201204800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silakov A.; Kamp C.; Reijerse E.; Happe T.; Lubitz W. Spectroelectrochemical characterization of the active site of the [FeFe] hydrogenase HydA1 from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Biochemistry 2009, 48 (33), 7780–7786. 10.1021/bi9009105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder D. W.; Ratzloff M. W.; Bruschi M.; Greco C.; Koonce E.; Peters J. W.; King P. W. Investigations on the role of proton-coupled electron transfer in hydrogen activation by [FeFe]-hydrogenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136 (43), 15394–15402. 10.1021/ja508629m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler M.; Senger M.; Duan J.; Esselborn J.; Wittkamp F.; Hofmann E.; Apfel U.-P.; Stripp S. T.; Happe T. Accumulating the hydride state in the catalytic cycle of [FeFe]-hydrogenases. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8 (1), 16115. 10.1038/ncomms16115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder D. W.; Guo Y.; Ratzloff M. W.; King P. W. Identification of a catalytic iron-hydride at the H-cluster of [FeFe]-hydrogenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (1), 83–86. 10.1021/jacs.6b11409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelmenschikov V.; Birrell J. A.; Pham C. C.; Mishra N.; Wang H.; Sommer C.; Reijerse E.; Richers C. P.; Tamasaku K.; Yoda Y.; Rauchfuss T. B.; Lubitz W.; Cramer S. P. Reaction coordinate leading to H2 production in [FeFe]-hydrogenase identified by nuclear resonance vibrational spectroscopy and density functional theory. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (46), 16894–16902. 10.1021/jacs.7b09751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham C. C.; Mulder D. W.; Pelmenschikov V.; King P. W.; Ratzloff M. W.; Wang H.; Mishra N.; Alp E. E.; Zhao J.; Hu M. Y.; Tamasaku K.; Yoda Y.; Cramer S. P. Terminal hydride species in [FeFe]-hydrogenases are vibrationally coupled to the active site environment. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57 (33), 10605–10609. 10.1002/anie.201805144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reijerse E. J.; Pham C. C.; Pelmenschikov V.; Gilbert-Wilson R.; Adamska-Venkatesh A.; Siebel J. F.; Gee L. B.; Yoda Y.; Tamasaku K.; Lubitz W.; Rauchfuss T. B.; Cramer S. P. Direct observation of an iron-bound terminal hydride in [FeFe]-hydrogenase by nuclear resonance vibrational spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (12), 4306–4309. 10.1021/jacs.7b00686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lautier T.; Ezanno P.; Baffert C.; Fourmond V.; Cournac L.; Fontecilla-Camps J. C.; Soucaille P.; Bertrand P.; Meynial-Salles I.; Léger C. The quest for a functional substrate access tunnel in FeFe hydrogenase. Faraday Discuss. 2011, 148 (0), 385–407. 10.1039/C004099C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorent C.; Katz S.; Duan J.; Kulka C. J.; Caserta G.; Teutloff C.; Yadav S.; Apfel U.-P.; Winkler M.; Happe T.; Horch M.; Zebger I. Shedding light on proton and electron dynamics in [FeFe] hydrogenases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142 (12), 5493–5497. 10.1021/jacs.9b13075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esselborn J.; Muraki N.; Klein K.; Engelbrecht V.; Metzler-Nolte N.; Apfel U. P.; Hofmann E.; Kurisu G.; Happe T. A structural view of synthetic cofactor integration into [FeFe]-hydrogenases. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7 (2), 959–968. 10.1039/C5SC03397G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senger M.; Mebs S.; Duan J.; Shulenina O.; Laun K.; Kertess L.; Wittkamp F.; Apfel U. P.; Happe T.; Winkler M.; Haumann M.; Stripp S. T. Protonation/reduction dynamics at the [4Fe-4S] cluster of the hydrogen-forming cofactor in [FeFe]-hydrogenases. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20 (5), 3128–3140. 10.1039/C7CP04757F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mebs S.; Duan J.; Wittkamp F.; Stripp S. T.; Happe T.; Apfel U.-P.; Winkler M.; Haumann M. Differential protonation at the catalytic six-iron cofactor of [FeFe]-hydrogenases revealed by 57Fe nuclear resonance X-ray scattering and quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics analyses. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58 (6), 4000–4013. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b00100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew S. G. The redox potential of dithionite and SO–2 from equilibrium reactions with flavodoxins, methyl viologen and hydrogen plus hydrogenase. Eur. J. Biochem. 1978, 85 (2), 535–547. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb12269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirts E. N.; Petrik I. D.; Hosseinzadeh P.; Nilges M. J.; Lu Y. A designed heme-[4Fe-4S] metalloenzyme catalyzes sulfite reduction like the native enzyme. Science 2018, 361 (6407), 1098–1101. 10.1126/science.aat8474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell R.; Sandalova T.; Hellman U.; Lindqvist Y.; Schneider G. Siroheme- and [Fe4-S4]-dependent NirA from Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a sulfite reductase with a covalent Cys-Tyr bond in the active site. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280 (29), 27319–28. 10.1074/jbc.M502560200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel L. M.; Murphy M. J.; Kamin H. Reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate-sulfite reductase of enterobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 1973, 248 (1), 251–264. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)44469-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanifuji K.; Lee C. C.; Sickerman N. S.; Tatsumi K.; Ohki Y.; Hu Y.; Ribbe M. W. Tracing the ‘ninth sulfur’ of the nitrogenase cofactor via a semi-synthetic approach. Nat. Chem. 2018, 10 (5), 568–572. 10.1038/s41557-018-0029-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackmore R. S.; Gadsby P. M. A.; Greenwood C.; Thomson A. J. Spectroscopic studies of partially reduced forms of Wolinella succinogenes nitrite reductase. FEBS Lett. 1990, 264 (2), 257–262. 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80262-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa C.; Moura J. J. G.; Moura I.; Wang Y.; Huynh B. H. Redox properties of cytochrome c nitrite reductase from Desulfovibrio desulfuricans ATCC 27774. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271 (38), 23191–23196. 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega J. M.; Kamin H. Spinach nitrite reductase. Purification and properties of a siroheme-containing iron-sulfur enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 1977, 252 (3), 896–909. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)75183-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlpine A. S.; McEwan A. G.; Shaw A. L.; Bailey S. Molybdenum active centre of DMSO reductase from Rhodobacter capsulatus: crystal structure of the oxidised enzyme at 1.82-Å resolution and the dithionite-reduced enzyme at 2.8-Å resolution. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 1997, 2 (6), 690–701. 10.1007/s007750050185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hao B.; Zhao G.; Kang P. T.; Soares J. A.; Ferguson T. K.; Gallucci J.; Krzycki J. A.; Chan M. K. Reactivity and chemical synthesis of L-pyrrolysine- the 22nd genetically encoded amino acid. Chem. Biol. 2004, 11 (9), 1317–24. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell W. K.; Stålhandske C. M. V.; Xia J.; Scott R. A.; Lindahl P. A. Spectroscopic, redox, and structural characterization of the Ni-labile and nonlabile forms of the acetyl-CoA synthase active site of carbon monoxide dehydrogenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120 (30), 7502–7510. 10.1021/ja981165z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Golden E.; Karton A.; Vrielink A. High-resolution structures of cholesterol oxidase in the reduced state provide insights into redox stabilization. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2014, 70 (12), 3155–66. 10.1107/S139900471402286X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mager H. I.; Tu S. C. Dithionite treatment of flavins: spectral evidence for covalent adduct formation and effect on in vitro bacterial bioluminescence. Photochem. Photobiol. 1990, 51 (2), 223–9. 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1990.tb01707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall S. A.; Fisher K.; Ni Cheallaigh A.; White M. D.; Payne K. A.; Parker D. A.; Rigby S. E.; Leys D. Oxidative maturation and structural characterization of prenylated FMN binding by UbiD, a decarboxylase involved in bacterial ubiquinone biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292 (11), 4623–4637. 10.1074/jbc.M116.762732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolphin D. H.; Johnson A. W.; Shaw N. Sulphitocobalamin. Nature 1963, 199 (4889), 170–171. 10.1038/199170b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salnikov D. S.; Silaghi-Dumitrescu R.; Makarov S. V.; van Eldik R.; Boss G. R. Cobalamin reduction by dithionite. Evidence for the formation of a six-coordinate cobalamin(II) complex. Dalton Trans. 2011, 40 (38), 9831–4. 10.1039/c1dt10219b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z.-Y.; Ledbetter R.; Shaw S.; Pence N.; Tokmina-Lukaszewska M.; Eilers B.; Guo Q.; Pokhrel N.; Cash V. L.; Dean D. R.; Antony E.; Bothner B.; Peters J. W.; Seefeldt L. C. Evidence that the Pi release event is the rate-limiting step in the nitrogenase catalytic cycle. Biochemistry 2016, 55 (26), 3625–3635. 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer M. S. Chemistry of sodium dithionite. Part 1.—Kinetics of decomposition in aqueous bisulphite solutions. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1967, 63 (0), 2510–2515. 10.1039/TF9676302510. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wayman M.; Lem W. J. Decomposition of aqueous dithionite. Part II. A reaction mechanism for the decomposition of aqueous sodium dithionite. Can. J. Chem. 1970, 48 (5), 782–787. 10.1139/v70-127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer J. Zur Kenntnis der hydroschwefligen Säure. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1903, 34 (1), 43–61. 10.1002/zaac.19030340103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rinker R. G.; Gordon T. P.; Mason D. M.; Sakaida R. R.; Corcoran W. H. Kinetics and mechanism of the air oxidation of the dithionite ion (S2O42-) in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. 1960, 64 (5), 573–581. 10.1021/j100834a015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Selwyn L.; Tse S. The chemistry of sodium dithionite and its use in conservation. Stud. Conserv. 2008, 53 (sup2), 61–73. 10.1179/sic.2008.53.Supplement-2.61. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bishenden E.; Donaldson D. J. Ab initio study of SO2 + H2O. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102 (24), 4638–4642. 10.1021/jp980160l. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R. K.; Scuderi D.; Maitre P.; Chiavarino B.; Crestoni M. E.; Fornarini S. Elusive sulfurous acid: gas-phase basicity and IR signature of the protonated species. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6 (9), 1605–1610. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b00450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voegele A. F.; Tautermann C. S.; Loerting T.; Hallbrucker A.; Mayer E.; Liedl K. R. About the stability of sulfurous acid (H2SO3) and its dimer. Chem. - Eur. J. 2002, 8 (24), 5644–5651. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolet Y.; Lemon B. J.; Fontecilla-Camps J. C.; Peters J. W. A novel FeS cluster in Fe-only hydrogenases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000, 25 (3), 138–143. 10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01536-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J.; Kim K.; King P.; Seibert M.; Schulten K. Finding gas diffusion pathways in proteins: application to O2 and H2 transport in CpI [FeFe]-hydrogenase and the role of packing defects. Structure 2005, 13 (9), 1321–1329. 10.1016/j.str.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund L.; Hofer T. S.; Pribil A. B.; Rode B. M.; Persson I. On the structure and dynamics of the hydrated sulfite ion in aqueous solution - an ab initio QMCF MD simulation and large angle X-ray scattering study. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41 (17), 5209–5216. 10.1039/c2dt12467j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Maciá P.; Galle L. M.; Bjornsson R.; Lorent C.; Zebger I.; Yoda Y.; Cramer S. P.; DeBeer S.; Span I.; Birrell J. A. Caught in the Hinact: crystal structure and spectroscopy reveal a sulfur bound to the active site of an O2-stable state of [FeFe] hydrogenase. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59 (38), 16786–16794. 10.1002/anie.202005208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldet G.; Brandmayr C.; Stripp S. T.; Happe T.; Cavazza C.; Fontecilla-Camps J. C.; Armstrong F. A. Electrochemical kinetic investigations of the reactions of [FeFe]-hydrogenases with carbon monoxide and oxygen: comparing the importance of gas tunnels and active-site electronic/redox effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131 (41), 14979–14989. 10.1021/ja905388j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamska-Venkatesh A.; Krawietz D.; Siebel J.; Weber K.; Happe T.; Reijerse E.; Lubitz W. New redox states observed in [FeFe] hydrogenases reveal redox coupling within the H-cluster. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136 (32), 11339–11346. 10.1021/ja503390c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemon B. J.; Peters J. W. Binding of exogenously added carbon monoxide at the active site of the iron-only hydrogenase (CpI) from Clostridium pasteurianum. Biochemistry 1999, 38 (40), 12969–12973. 10.1021/bi9913193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mebs S.; Kositzki R.; Duan J.; Kertess L.; Senger M.; Wittkamp F.; Apfel U.-P.; Happe T.; Stripp S. T.; Winkler M.; Haumann M. Hydrogen and oxygen trapping at the H-cluster of [FeFe]-hydrogenase revealed by site-selective spectroscopy and QM/MM calculations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 2018, 1859 (1), 28–41. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Maciá P.; Birrell J. A.; Lubitz W.; Rüdiger O. Electrochemical investigations on the inactivation of the [FeFe] hydrogenase from Desulfovibrio desulfuricans by O2 or light under hydrogen-producing conditions. ChemPlusChem 2017, 82 (4), 540–545. 10.1002/cplu.201600508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaac A.; Wain A. J.; Compton R. G.; Livingstone C.; Davis J. A novel electroreduction strategy for the determination of sulfite. Analyst 2005, 130 (10), 1343–1344. 10.1039/b509721e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebel J. F.; Adamska-Venkatesh A.; Weber K.; Rumpel S.; Reijerse E.; Lubitz W. Hybrid [FeFe]-hydrogenases with modified active sites show remarkable residual enzymatic activity. Biochemistry 2015, 54 (7), 1474–1483. 10.1021/bi501391d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Maciá P.; Kertess L.; Burnik J.; Birrell J. A.; Hofmann E.; Lubitz W.; Happe T.; Rüdiger O. His-ligation to the [4Fe-4S] subcluster tunes the catalytic bias of [FeFe] hydrogenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (1), 472–481. 10.1021/jacs.8b11149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M.; Sulc F.; Ribbe M. W.; Farmer P. J.; Burgess B. K. Direct assessment of the reduction potential of the [4Fe-4S]1+/0 couple of the Fe protein from Azotobacter vinelandii. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124 (41), 12100–12101. 10.1021/ja026478f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent K. A.; Tilley G. J.; Quammie N. C.; Streeter I.; Burgess B. K.; Cheesman M. R.; Armstrong F. A. Instantaneous, stoichiometric generation of powerfully reducing states of protein active sites using Eu(II) and polyaminocarboxylate ligands. Chem. Commun. 2003, (20), 2590–2591. 10.1039/b308188e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steuber J.; Arendsen A. F.; Hagen W. R.; Kroneck P. M. H. Molecular properties of the dissimilatory sulfite reductase from Desulfovibrio desulfuricans (Essex) and comparison with the enzyme from Desulfovibrio vulgaris (Hildenborough). Eur. J. Biochem. 1995, 233 (3), 873–879. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.873_3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison G.; Curle C.; Laishley E. J. Purification and characterization of an inducible dissimilatory type sulfite reductase from Clostridium pasteurianum. Arch. Microbiol. 1984, 138 (1), 72–78. 10.1007/BF00425411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.; Shrager J.; Jain M.; Chang C.-W.; Vallon O.; Grossman A. R. Insights into the survival of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii during sulfur starvation based on microarray analysis of gene expression. Eukaryotic Cell 2004, 3 (5), 1331–1348. 10.1128/EC.3.5.1331-1348.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baffert C.; Kpebe A.; Avilan L.; Brugna M., Chapter Three - Hydrogenases and H2 metabolism in sulfate-reducing bacteria of the Desulfovibrio genus. In Advances in Microbial Physiology; Poole R. K., Ed.; Academic Press: 2019; Vol. 74, pp 143–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.