Abstract

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) CAR-T cell therapy targeting CD20 can be a novel adoptive cell therapy for canine patients with B-cell malignancy. After injection of the CAR-T cells in vivo, monitoring circulating CAR-T cells is essential to prove in vivo persistence of CAR-T cells. In this study, we developed a novel monoclonal antibody against canine CD20 CAR, whose single-chain variable fragment was derived from the our previously reported anti-canine CD20 therapeutic antibody. Furthermore, we proved that this monoclonal antibody can detect therapeutic anti-canine CD20 chimeric antibody in the serum from healthy beagle dogs injected with the therapeutic antibody for safety study. This monoclonal antibody is a useful tool for monitoring both canine CD20-CAR-T cells and anti-canine CD20 therapeutic antibody for canine lymphoma.

Keywords: adoptive immunotherapy, canine, CD20, chimeric antigen receptor T cell, monoclonal antibody

In veterinary medicine, canine B cell lymphoma is the most common hematopoietic neoplasm and is considered as a relevant model for human non-Hodgkin lymphoma [5, 21]. Many cases show a good response to standard multidrug chemotherapy; however, the onset of relapsed or refractory disease impedes the long-term control of the disease. Moreover, drug resistance is very common and makes the treatment even more difficult. Therefore, it is necessary to develop further treatment options.

The novel cancer immunotherapy targeting CD19 and CD20, including chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy and monoclonal antibody therapy, has been developed, and proved to be effective for human B cell hematologic malignancies [2, 18]. As with human medicine, these novel immunotherapies have been developed in veterinary medicine. In the literature, there are a few studies on canine CAR-T cell therapy [10, 11, 14, 19]. For establishing the CAR-T cell therapy for canine lymphoma, we developed the strategy of preparing canine CD20-CAR-T cells in the previous report [16]. It has been suggested that many factors were influencing the clinical efficacy in CAR-T cell therapy. They were not fully elucidated; however, in vivo expansion and persistence of CAR-T cells are considered critical predictive factors of clinical responses [3, 15]. Thus, to assess the therapeutic potential of CAR-T cells, investigators essentially measure the persistence of adoptively infused T cells. However, we have no method to monitor the canine CD20-CAR-T cells in vivo.

In addition to CAR-T cell therapy, human studies have reported the effectiveness of anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy for treating B cell malignancies [18]. Although there is no commercially available therapeutic antibody therapy against canine CD20, several studies have reported the development of the novel anti-canine CD20 monoclonal antibodies showing anti-tumor efficacy in vitro [4, 7]. However, the clinical efficacy of these antibodies in patient dogs remain unknown. Our laboratory recently developed the novel rat anti-canine CD20 antibody, 4E1-7 [12]. Based on 4E1-7 antibody, the chimeric anti-canine CD20 antibody, 4E1-7-B, and the chimeric defucosylated anti-canine CD20 antibody, 4E1-7-B_f, were generated, and the latter was found to have dramatically high in vitro antitumor activity [12], and clinical trials for dogs with B cell lymphoma are under preparation. In this therapy, pharmacokinetic studies are essential to determine individual variability and understand the relationships between antibody concentration and clinical efficacy.

In this study, we established a new monoclonal antibody that can detect the single-chain variable fragment (scFv) region of canine CD20 CAR. We demonstrated that this antibody can be used to detect CD20-CAR-expressing cells. Moreover, we developed ELISA using this established antibody to detect therapeutic anti-canine CD20 antibody, and then the blood concentration of therapeutic anti-canine CD20 antibody was measured in healthy dogs.

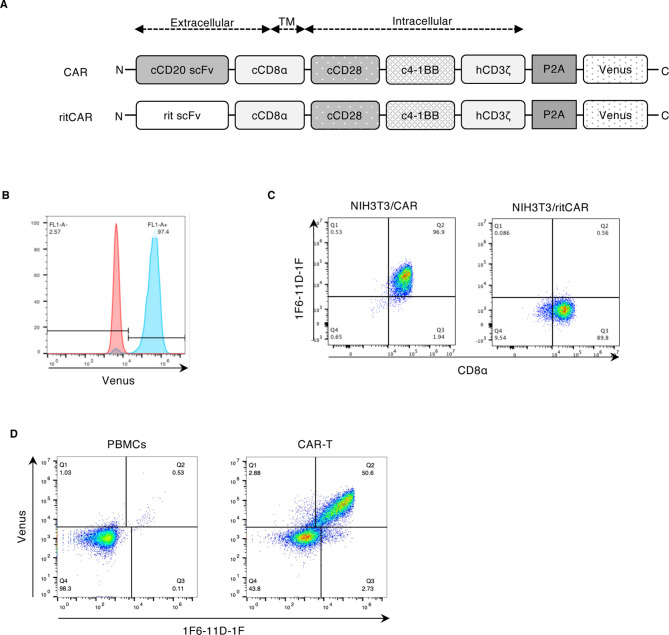

This study firstly aims to establish a method for monitoring the CD20 CAR-T cells in vivo. For that, we examined whether the commercially available anti-rat IgG secondary antibody could detect the scFV region of CD20 CAR, since the scFv region of CD20 CAR construct was derived from rat monoclonal antibody (Fig. 1A). For this purpose, canine T cell lymphoma cell line (CLC) cultured in R10 complete medium (RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 55 μM 2-mercaptoethanol) was transduced with CD20 CAR construct to obtain the cell lines stably expressing CAR, as described previously [16]. The CAR construct consisted of the scFv of anti-CD20 antibody, 4E1-7 [12] linked to the canine CD8α hinge and transmembrane domain, followed by the canine CD28 and 4-1BB costimulatory domain, and human CD3ζ signaling domain (Fig. 1A), followed by a P2A peptide fused to Venus fragments for the coexpresion of CARs with a fluorescent protein. This CAR-P2A-Venus construct was ligated into the MSGV vector (Addgene, Cambridge, MA, USA). Retrovirus particles were collected from the PG-13 producer cell line, cultured in D10 complete medium (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with high glucose, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 55 μM 2-mercaptoethanol), transfected with the construct above, and used to transduce the CLC cells. After viral transduction, CD20-CAR-expressing cells (CLC/CAR) were sorted by Venus expression (data not shown). For flow cytometrc analysis, the CLC/CAR cells were incubated with Fixable Viability Dye eFluor 780 (eBioscience, Inc., Vienna, Austria), followed by the staining with anti-rat IgG secondary antibodies; goat anti-rat IgG-PE (sc-3740; dilution 1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA), rabbit F (ab’) 2 anti-rat IgG-RPE (STAR20A; dilution 1:10; Serotec, Oxford, UK), goat anti-rat IgG (H+L)-PE (3050; dilution 1:250; Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA), goat anti-rat IgG-Biotin (sc-2041; dilution 1:1,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) or DyLight 649 goat anti-rat IgG (405411; dilution 1:500; BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA). Incubation with biotin-conjugated antibody was followed by incubation with streptavidin-PE (dilution 1:1,000, eBioscience, Inc.). Accuri C6 (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to analyze the samples, and FlowJo software (BD Biosciences) was used to analyze the results. However, none of these five kinds of anti-rat IgG antibodies bound CD20 CAR (data not shown), probably because these polyclonal antibodies mainly recognized Fc region of rat IgG antibody instead of variable region. Therefore, we decided to develop the monoclonal antibody against CD20 CAR.

Fig. 1.

Generation of anti-CD20-chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) monoclonal antibody. (A) Schematic diagram of the canine CD20-CAR-expressing construct and ritCAR-expressing construct used as a control. (B) Establishment of CD20 CAR-expressing murine cells for immunization. NIH3T3 cells were retrovirally transduced with the CAR-expressing vector (NIH3T3/CAR). Wild-type NIH3T3 (red) and NIH3T3/CAR (blue) cells were assessed by Venus expression. (C) CD20 CAR detection using the established antibody, 1F6-11D-1F. NIH3T3/CAR and NIH3T3/ritCAR cells were stained with 1F6-11D-1F and anti-canine CD8α antibodies. Both cells expressed canine CD8α, but CD20 -CAR was expressed only in NIH3T3/CAR, indicating 1F6-11D-1F is specific to CD20-CAR. (D) CAR-T cells were stained with 1F6-11D-1F. Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells were isolated from a healthy beagle, and stimulated by Iinterleukin-2 and phytohemagglutinin, followed by the transduction of CD20 CAR, as described in the text. CD20 CAR-T cells were stained with the established anti-CD20-CAR antibody (1F6-11D-1F). The dot plot shows Venus expression versus 1F6-11D-1F staining.

The CAR-P2A-Venus construct (Fig. 1A) was ligated into the pMXs-IP retroviral vector to obtain the NIH3T3 cells expressing CD20 CAR used for immunization. By transient transfection of Plat-E cells with the CD20 CAR-encoding retrovirus vector, retrovirus particles were generated. Supernatants containing the retrovirus were collected and used to transduce the NIH3T3 cells. To select the stably transduced cells, the cells were cultured in the presence of puromycin (1 μg/ml), resulting in NIH3T3/CAR cells (Fig. 1B). For comparison, ritCAR-P2A-Venus construct in the pMXs-IP was also transduced into NIH3T3, resulting in NIH3T3/ritCAR cells. The ritCAR-P2A-Venus was same construct as the CAR-P2A-Venus except that this had the scFv of anti-human CD20 therapeutic antibody, rituximab.

We immunized mice with NIH3T3/CAR cells to establish the monoclonal antibody against CD20 CAR. All animal studies were conducted in accordance with the Yamaguchi University Animal Care and Use Committee Regulations (Approval number 419). By immunization with NIH3T3/CAR cells, a panel of antibodies against CD20-CAR was obtained, as previously described [20]. While a total of 384 clones were screened by ELISA and flow cytometry, hybridoma cells that produced antibodies against scFv-CD20 were selected by reactivity with both cell surface CAR on NIH3T3/CAR cells and anti-canine CD20 antibody. For flow cytometric screening, NIH3T3/CAR cells were stained with hybridoma supernatant, followed by staining with DyLight 649-labeled anti-mouse IgG antibody (dilution 1:200, BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) as a secondary antibody. For ELISA screening assay, ninety-six-well plates (Maxisorp; Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated with anti-CD20 antibody (4E1-7-B) in immobilization buffer (100 μl/well, 0.05 M sodium carbonate solution, pH 9.6) and incubated for 15–18 hr at 4°C. After incubation, the wells were washed three times with the washing buffer (0.05% Tween 20 in PBS), and the nonspecific binding in the wells were blocked with the blocking buffer (200 μl/well, 3% BSA in PBS) for 1 hr at 37°C. After an additional washing step, 100 μl of hybridoma supernatant for screening was added to each well, and the plates were incubated for 1 hr at 37°C. After washing the plates five times, 100 μl of detection antibody solution was added to each well, and then the plates were incubated for 1 hr at 37°C. Mouse anti-canine Ig mix secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Tokyo, Japan), labeled with HRP using Peroxidase Labeling Kit-NH2 (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan), was used as a detection antibody. After another washing step, 100 μl of KPL ABTS Peroxidase Substrate Solution (SeraCare, Milford, MA, USA) was added to each well, and plates were incubated to react for 10 min at 37°C in the dark. With a microplate reader, the absorbance was measured at 405 nm. Hybridoma cells that produced antibodies positive for CD20 CAR on NIH3T3/CAR and anti-canine CD20 antibody, were identified by cell enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and flow cytometry, and the resulting hybridoma cells were cloned by limiting dilution. After hybridoma selection and cloning, we obtained a single hybridoma clone, 1F6-11D-1F. Protein G Sepharose 4 Fast Flow (GE Healthcare Japan, Tokyo, Japan) was used to purify the monoclonal antibody after the replacement of the culture media with serum-free media. The subclass of 1F6-11D-1F was determined to be mouse IgG2b kappa by Mouse Immunoglobulin Isotyping kit (Antagen Biosciences, Inc., MA, USA).

Firstly, we verified if this antibody bound to the cCD20 scFv in CAR, not other extracellular part of CAR-construct. We used NIH3T3/rit-CAR cells, which expressed the same construct except the scFv part. As shown in Fig. 1C, both cells were stained with anti-CD8α antibody (F3B2) [17], but 1F6-11D-1F bound to NIH3T3/CAR, but not to NIH3T3/rit-CAR. This means that 1F6-11D-1F are specific to cCD20 scFV. Next, we confirmed whether this antibody detects the CAR-expression in CD20-CAR transduced T cells. Canine CD20 CAR-T cells were obtained, as previously described [16]. In brief, Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated using Lymphoprep (Axis-Shield, Oslo, Norway) gradient centrifugation and then stimulated in R10 complete medium in the presence of 200 U/ml of recombinant human IL-2 (Proleukin; Novartis, Basel, Switzerland) and 5 μg/ml of phytohemagglutinin (PHA) for 72 hr. After initial stimulation, the retrovirus-containing supernatants, collected from PG-13 packaging cells transfected with CD20-CAR construct (Fig. 1A), were added to the RetroNectin (TaKaRa Bio, Kusatsu, Japan) -coated plate, and this plate was centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 2 hr at 4°C to prepare the virus-bound plate. After retroviral transduction, CD20-CAR-T cells were subsequently expanded with 200 U/ml IL-2, and used in the following experiments.

It was confirmed that 1F6-11D-1F detected only CAR-expressing PBMCs shown as the population of Venus fluorescent protein by flow cytometry, whereas 1F6-11D-1F did not bind to nontransduced PBMCs that were similarly prepared as CAR- expressing PBMCs except using supernatants containing no virus (Fig. 1D). Among the technical approaches to assessing survival of infused CAR-T cells after in vivo injection, quantitative PCR using CAR-specific primers in the most common method [8, 13]. However, flow cytometric analysis using CAR-specific antibody is favorable because it allows additional evaluation such as multiparameter analysis and cell sorting [9]. Flow cytometric analysis of CAR-T cells has another advantage; it enables the detection of living cells. Our results indicate that 1F6-11D-1F can be a useful tool to detect and monitor the infused CD20 CAR-T cells from blood samples of the infused dogs.

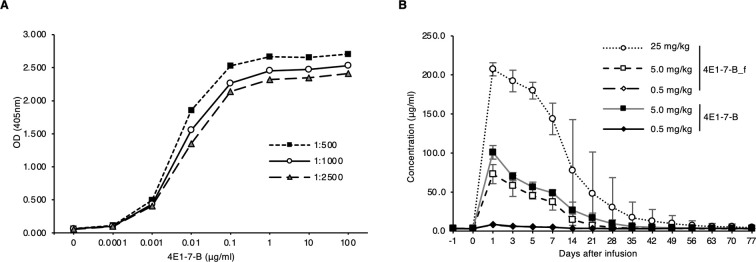

Since 1F6-11D-1F was raised against scFv region derived from anti-canine CD20 antibody, 4E1-7, we assessed 1F6-11D-1F to determine whether it could be used to detect chimeric anti-canine CD20 therapeutic antibody [12], 4E1-7-B, by ELISA. ELISA was performed as described above, where ninety-six-well plates were coated with 1F6-11D-1F, and serially diluted 4E1-7-B antibody was added, followed by the addition of detection antibody, mouse anti-canine Ig mix secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Tokyo, Japan) labeled with HRP using Peroxidase Labeling Kit-NH2 (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) at serial dilution (1:500, 1,000 and 2,500). Plate-coated 1F6-11D-1F was found to bind to serially diluted 4E1-7-B as shown in Fig. 2A. This result indicates that the blood concentration of 4E1-7-B in the anti-CD20 antibody therapy can be measured using 1F6-11D-1F.

Fig. 2.

The measurement of chimeric anti-canine CD20 antibody. (A) Plates were coated with 1F6-11D-1F (1 μg/ml), followed by incubation with serially diluted chimeric anti-canine CD20 antibody (4E1-7-B). Antibody binding was detected by HRP-conjugated anti-dog IgG antibody at indicated dilutions (1:500, 1:1,000 and 1:2,500). Substrate solution was added and absorbance at 405 nm was measured. (B) Pharmacokinetic profile of chimeric anti-canine CD20 antibody in the serum from healthy beagle dogs. Fifteen healthy beagles (of three dogs in each group) were injected with either of rat-dog chimeric anti-canine CD20 antibody (4E1-7-B) or the defucosylated antibody (4E1-7-B_f) at the indicated dose. The concentration of anti-canine CD20 antibody in dog sera was measured by ELISA using plate-coated 1F6-11D-1F. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

We next conducted a pharmacokinetic study of anti-canine CD20 therapeutic antibodies, fucosylated antibody, 4E1-7-B and defucosylated antibody, 4E1-7-B_f, injected into the healthy dogs, using the ELISA developed in this study. Defucosylated antibody, 4E1-7-B_f, was developed based on 4E1-7-B chimeric antibody to enhance the function of antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity in our previous study [12]. Serum samples for this study were derived from the healthy beagle dogs used in our previous study [12]. In that study, 15 healthy beagles (of three dogs in each group) were injected with either rat-dog chimeric anti-canine CD20 antibody (4E1-7-B) or the defucosylated antibody (4E1-7-B_f). One of two doses (either 0.5 mg/kg or 5.0 mg/kg) of 4E1-7-B was intravenously injected once on day 0. As for 4E1-7-B_f, in addition to the two doses (either 0.5 mg/kg or 5.0 mg/kg), much higher doses (25 mg/kg) was also injected in anticipation of clinical use. For measurement of administered antibody concentration by ELISA assay, serum was collected from each dog at the indicated time point. The pharmacokinetic study revealed a dose-dependent increase in the concentration and duration of infused therapeutic antibodies (Fig. 2B). In all dose settings, the blood levels of the administered antibodies peaked the next day and gradually decreased over 2 to 3 weeks. Even a dose of 0.5 mg/kg produce very low blood levels as compared with other two doses, though this dose still induced the B cell depletion in our previous study [12]. No significant difference was observed between fucosylated and defucosylated antibodies. Pharmacokinetic study on antibody therapy is essential to determine the basis of individual variability. The pharmacokinetic studies of anti-human CD20 therapeutic antibody, rituximab, have revealed that there exists wide interindividual variability, and high serum drug concentrations appear to correlate with good clinical response [1, 6]. Though there was no wide interindividual variability in this study, further pharmacokinetics studies on patients with various tumor burdens are needed to understand the factors correlating with clinical efficacy.

In summary, we established a novel monoclonal antibody, 1F6-11D-1F, against the scFv region of the anti-canine CD20 antibody, 4E1-7, and demonstrated that this antibody can detect CD20 CAR-expressing cells in flow cytometry. This antibody has also potential to be applied for detecting anti-canine CD20 therapeutic antibody. This study will be helpful for further investigation of canine CAR-T cell therapy and antibody therapy.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Takuya Mizuno has received research funding from Nippon Zenyaku Kogyo Co., Ltd. The rest of the authors declare no other conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the technical expertise of the DNA Core Facility of the Center for Gene Research, Yamaguchi University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berinstein N. L., Grillo-López A. J., White C. A., Bence-Bruckler I., Maloney D., Czuczman M., Green D., Rosenberg J., McLaughlin P., Shen D.1998. Association of serum Rituximab (IDEC-C2B8) concentration and anti-tumor response in the treatment of recurrent low-grade or follicular non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Ann. Oncol. 9: 995–1001. doi: 10.1023/A:1008416911099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chavez J. C., Locke F. L.2018. CAR T cell therapy for B-cell lymphomas. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Haematol. 31: 135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2018.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guedan S., Posey A. D., Jr, Shaw C., Wing A., Da T., Patel P. R., McGettigan S. E., Casado-Medrano V., Kawalekar O. U., Uribe-Herranz M., Song D., Melenhorst J. J., Lacey S. F., Scholler J., Keith B., Young R. M., June C. H.2018. Enhancing CAR T cell persistence through ICOS and 4-1BB costimulation. JCI Insight 3: e96976. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.96976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ito D., Frantz A. M., Modiano J. F.2014. Canine lymphoma as a comparative model for human non-Hodgkin lymphoma: recent progress and applications. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 159: 192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2014.02.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ito D., Brewer S., Modiano J. F., Beall M. J.2015. Development of a novel anti-canine CD20 monoclonal antibody with diagnostic and therapeutic potential. Leuk. Lymphoma 56: 219–225. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2014.914193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jäger U., Fridrik M., Zeitlinger M., Heintel D., Hopfinger G., Burgstaller S., Mannhalter C., Oberaigner W., Porpaczy E., Skrabs C., Einberger C., Drach J., Raderer M., Gaiger A., Putman M., Greil R., Arbeitsgemeinschaft Medikamentöse Tumortherapie (AGMT) Investigators.2012. Rituximab serum concentrations during immuno-chemotherapy of follicular lymphoma correlate with patient gender, bone marrow infiltration and clinical response. Haematologica 97: 1431–1438. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.059246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain S., Aresu L., Comazzi S., Shi J., Worrall E., Clayton J., Humphries W., Hemmington S., Davis P., Murray E., Limeneh A. A., Ball K., Ruckova E., Muller P., Vojtesek B., Fahraeus R., Argyle D., Hupp T. R.2016. The development of a recombinant scFv monoclonal antibody targeting canine CD20 for use in comparative medicine. PLoS One 11: e0148366. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kochenderfer J. N., Wilson W. H., Janik J. E., Dudley M. E., Stetler-Stevenson M., Feldman S. A., Maric I., Raffeld M., Nathan D. A. N., Lanier B. J., Morgan R. A., Rosenberg S. A.2010. Eradication of B-lineage cells and regression of lymphoma in a patient treated with autologous T cells genetically engineered to recognize CD19. Blood 116: 4099–4102. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-281931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee D. W., Kochenderfer J. N., Stetler-Stevenson M., Cui Y. K., Delbrook C., Feldman S. A., Fry T. J., Orentas R., Sabatino M., Shah N. N., Steinberg S. M., Stroncek D., Tschernia N., Yuan C., Zhang H., Zhang L., Rosenberg S. A., Wayne A. S., Mackall C. L.2015. T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet 385: 517–528. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61403-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mata M., Gottschalk S.2016. Man’s best friend: utilizing naturally occurring tumors in dogs to improve chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for human cancers. Mol. Ther. 24: 1511–1512. doi: 10.1038/mt.2016.173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mata M., Vera J. F., Gerken C., Rooney C. M., Miller T., Pfent C., Wang L. L., Wilson-Robles H. M., Gottschalk S.2014. Toward immunotherapy with redirected T cells in a large animal model: ex vivo activation, expansion, and genetic modification of canine T cells. J. Immunother. 37: 407–415. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mizuno T., Kato Y., Kaneko M. K., Sakai Y., Shiga T., Kato M., Tsukui T., Takemoto H., Tokimasa A., Baba K., Nemoto Y., Sakai O., Igase M.2020. Generation of a canine anti-canine CD20 antibody for canine lymphoma treatment. Sci. Rep. 10: 11476. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-68470-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgan R. A., Dudley M. E., Wunderlich J. R., Hughes M. S., Yang J. C., Sherry R. M., Royal R. E., Topalian S. L., Kammula U. S., Restifo N. P., Zheng Z., Nahvi A., de Vries C. R., Rogers-Freezer L. J., Mavroukakis S. A., Rosenberg S. A.2006. Cancer regression in patients after transfer of genetically engineered lymphocytes. Science 314: 126–129. doi: 10.1126/science.1129003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Panjwani M. K., Smith J. B., Schutsky K., Gnanandarajah J., O’Connor C. M., Powell D. J., Jr, Mason N. J.2016. Feasibility and safety of RNA-transfected CD20-specific chimeric antigen receptor T cells in dogs with spontaneous B cell lymphoma. Mol. Ther. 24: 1602–1614. doi: 10.1038/mt.2016.146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rafiq S., Hackett C. S., Brentjens R. J.2020. Engineering strategies to overcome the current roadblocks in CAR T cell therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 17: 147–167. doi: 10.1038/s41571-019-0297-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakai O., Igase M., Mizuno T.2020. Optimization of canine CD20 chimeric antigen receptor T cell manufacturing and in vitro cytotoxic activity against B-cell lymphoma. Vet. Comp. Oncol. 18: 739–752. doi: 10.1111/vco.12602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakai O., Ii T., Uchida K., Igase M., Mizuno T.2020. Establishment and Characterization of Monoclonal Antibody Against Canine CD8 Alpha. Monoclon. Antib. Immunodiagn. Immunother. 39: 129–134. doi: 10.1089/mab.2020.0002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salles G., Barrett M., Foà R., Maurer J., O’Brien S., Valente N., Wenger M., Maloney D. G.2017. Rituximab in B-cell hematologic malignancies: a review of 20 years of clinical experience. Adv. Ther. 34: 2232–2273. doi: 10.1007/s12325-017-0612-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith J. B., Kazim Panjwani M., Schutsky K., Gnanandarajah J., Calhoun S., Cooper L., Mason N., Powell D. J.2015. Feasibility and safety of cCD20 RNA CAR-bearing T cell therapy for the treatment of canine B cell malignancies. J. Immunother. Cancer 3: 123. doi: 10.1186/2051-1426-3-S2-P123 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Umeki S., Suzuki R., Shimojima M., Ema Y., Yanase T., Iwata H., Okuda M., Mizuno T.2011. Characterization of monoclonal antibodies against canine P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1). Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 142: 119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2011.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zandvliet M.2016. Canine lymphoma: a review. Vet. Q. 36: 76–104. doi: 10.1080/01652176.2016.1152633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]