Abstract

Background

Focused ultrasound (FUS)-mediated blood–brain barrier (BBB) opening has shown efficacy in removal of amyloid plaque and improvement of cognitive functions in preclinical studies, but this is rarely reported in clinical studies. This study was conducted to evaluate the safety, feasibility and potential benefits of repeated extensive BBB opening.

Methods

In this open-label, prospective study, six patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) were enrolled at Severance Hospital in Korea between August 2020 and September 2020. Five of them completed the study. FUS-mediated BBB opening, targeting the bilateral frontal lobe regions over 20 cm3, was performed twice at three-month intervals. Magnetic resonance imaging, 18F-Florbetaben (FBB) positron emission tomography, Caregiver-Administered Neuropsychiatric Inventory (CGA-NPI) and comprehensive neuropsychological tests were performed before and after the procedures.

Results

FUS targeted a mean volume of 21.1 ± 2.7 cm3 and BBB opening was confirmed at 95.7% ± 9.4% of the targeted volume. The frontal-to-other cortical region FBB standardized uptake value ratio at 3 months after the procedure showed a slight decrease, which was statistically significant, compared to the pre-procedure value (− 1.6%, 0.986 vs1.002, P = 0.043). The CGA-NPI score at 2 weeks after the second procedure significantly decreased compared to baseline (2.2 ± 3.0 vs 8.6 ± 6.0, P = 0.042), but recovered after 3 months (5.2 ± 5.8 vs 8.6 ± 6.0, P = 0.89). No adverse effects were observed.

Conclusions

The repeated and extensive BBB opening in the frontal lobe is safe and feasible for patients with AD. In addition, the BBB opening is potentially beneficial for amyloid removal in AD patients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40035-021-00269-8.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, Focused ultrasound, Blood–brain barrier, Amyloid beta-peptides

Background

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia and is characterized by progressive memory decline. The pathological hallmarks of AD are extracellular amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles [1]. Since the discovery of Aβ in 1984, Aβ accumulation has been considered the initial event in the AD process, and many anti-amyloid trials have been conducted in AD patients [2]. However, so far no therapies have been found to delay the progression of cognitive and functional disability.

The failure of prior anti-amyloid trials has stimulated investigation of alternative treatment approaches [3]. One of the challenges to anti-amyloid trial is the determination of effective dosing protocols that enable anti-amyloid antibody to penetrate the blood–brain barrier (BBB) effectively without undesirable side effects such as amyloid-related imaging abnormalities. As such, focused ultrasound (FUS) with microbubble-mediated temporary BBB opening has been attracting attention for its role in improving the delivery of therapeutic agents to the brain [4].

In addition, BBB opening alone has an anti-amyloid effect. Several preclinical studies have demonstrated that the FUS-mediated BBB opening can reduce Aβ and phosphorylated tau burden and improve cognitive function [5–8]. Based on these results, two clinical trials of BBB opening for AD have been undertaken: the phase 1 clinical trial by Lipsman et al. targeting the right frontal lobe [9], and the phase 2 clinical trial by Rezai et al. targeting the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex [10]. The Lipsman’s study demonstrates for the first time the safety of BBB opening in humans, while Rezai et al. demonstrate an Aβ decrease after BBB opening [11]. However, neither study showed any significant improvement in cognitive impairment. In addition, several other clinical trials are currently ongoing or completed: the BBB opening trial using single-element FUS for early AD or mild cognitive impairment patients (NCT04118764) and BBB opening trial using an implanted FUS device for mild AD (NCT03119961).

Since Aβ deposition and subsequent changes widely occur throughout the brain and previous studies have reported a small-range opening of less than 3 cm3, in this study we aimed to evaluate extensive BBB opening of above 20 cm3. As the safety of BBB opening in very large areas has not yet been confirmed, in order to avoid serious potential complications from BBB opening of the mesial temporal area, we selected the prefrontal area which also has much accumulation of Aβ. The potential secondary benefits, such as cerebral Aβ removal or clinical improvement, which have been found in preclinical studies [5–8], were also assessed.

Methods

Study design

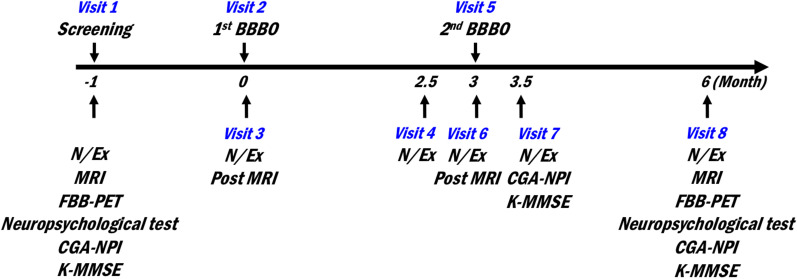

This study was an open-label, prospective study designed to evaluate the safety, feasibility and efficacy of repeated and extensive BBB opening of the bilateral frontal lobes. FUS-mediated BBB opening was performed twice at three-month intervals. Before the procedures, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), 18F-Florbetaben (FBB) positron emission tomography (PET) and comprehensive neuropsychological tests were performed. To assess the safety and feasibility, MRI was performed after each BBB opening procedure. To assess the efficacy, FBB PET and comprehensive neuropsychological tests were performed 3 months after the second procedure, a time point selected based on the concerns of learning effect due to repeated tests within a short period of time. Instead, Korean version of Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) and Caregiver-Administered Neuropsychiatric Inventory (CGA-NPI), which obtain patients' symptom information from their caregivers, were performed 2 weeks after the second procedure. The outline of study design is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Overview of the study design. BBBO, BBB opening; N/Ex, Neurological examination; MRI, magnetic-resonance imaging; FBB-PET, 18F-Florbetaben positron emission tomography; CGA-NPI, Caregiver-Administered Neuropsychiatric inventory; K-MMSE, Korean Version of Mini-mental State Examination

Participants

Participants were enrolled from AD patients who visited the neurology or neurosurgery outpatient clinic of our hospital. AD patients aged 50–85 and having a K-MMSE score of ≤ 23 were eligible for the study. All participants fulfilled the criteria for probable AD dementia with high levels of biomarker evidence, and were identified as having significant cerebral Aβ deposition on FBB PET and neuronal injury relevant for AD on 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET scans [12]. Those with contraindications to BBB opening with microbubble-enhanced focused ultrasound were excluded. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Additional file 1: Table S1. During the study period, the patients’ medications were maintained at the same dose.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

The study was approved by the Korean Food and Drug Administration and Institutional Review Board of our institution before study initiation (No. 1-2019-0095). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and their primary caregivers. The clinical trial registration information can be found at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/, identifier: NCT04526262.

Magnetic resonance-guided FUS (MRgFUS) procedure

BBB opening was performed with the MRgFUS system (ExAblate Neuro Model 4000 Type 2.0 [220 kHz] system, InSightec, Haifa, Israel) under continuous infusion of a microbubble contrast agent (Definity®) (250 ml N/S + 1.3 ml Definity®, infusion rate 180 ml/h). Target regions were selected in the bilateral frontal lobes, mainly the prefrontal area, and they were set around the boundary between gray matter and white matter in both frontal lobes, avoiding sulci, vessel, and ventricle. As the height of the area to be sonicated once was about 7–9 mm, the targets were set at 1–1.5 cm intervals in height to avoid overlap. The inferior target was selected at the area 1 cm above the ventral aspect of the frontal lobe, and the middle and superior targets were above it by one and two intervals, respectively. BBB opening was performed in the maximum volume to set, taking into account the recommended protocol of microbubble contrast for FUS-mediated BBB opening. The BBB opening was started with a power of 8 W, which was gradually increased until the target accumulated cavitation dose reached 0.4–0.65, up to a maximum power of 40 W. Sonication was performed for 90 s per session. When inertial cavitation was confirmed, sonication was stopped immediately. In the case where a sufficient dose was not reached despite sufficiently high power, an additional 120-s sonication was used. After completion of the procedure, a gadolinium-enhanced MRI was performed to verify BBB opening.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was the overall clinical and radiological safety and the feasibility of repetitive extensive BBB opening in the bilateral frontal lobes. Clinical safety assessments included vital signs, adverse effects, neurological examination, blood tests, and electrocardiography. Radiological safety was evaluated based on the brain MRI to detect any sign of hemorrhage, edema or any other adverse radiological events. Brain MRI was performed immediately after each procedure and three months after the second procedure.

The feasibility of BBB opening was evaluated by comparing post-procedure gadolinium-enhanced MRI scans with pre-procedure MRI scans. The contrast-enhanced area was manually segmented by two neurosurgeons who were not involved in the procedure, based on the immediate post-procedure gadolinium-enhanced MRI, after which the target volumes were compared through linear image-based registrations on the pre-procedure MRI scans in which the targets were planned. Results from the two independent observers were averaged.

Secondary outcome

Reduction of Aβ deposition

As previous studies have shown that cerebral Aβ accumulates even in the AD dementia stage [13], Aβ deposition was assessed with FBB PET using a Discovery 600 system (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) to identify the effect of localized FUS in the frontal lobe. FBB PET scans were carried out at screening (Visit 1) and 3 months after the second procedure (Visit 8). FBB PET images were linearly registered to the individual T1-weighted MRI scans at corresponding time point using rigid body transformation. Then, the reconstructed cortical surfaces and classified tissues from the CIVET processing pipeline (http://mcin.ca/civet) were linearly registered into the PET images by applying inverse transform matrices. We performed partial volume correction within gray and white matter regions using iterative deconvolution with a surface-based anatomically constructed filtering method that uses the representation of the volume between the inner and outer surfaces as a spatial constraint to the PET signal [14]. Then the corrected PET values were normalized to the cerebellar crus-I/II reference region, resulting in standardized uptake value ratios (SUVRs). Based on the Desikan-Killiany-Tourville (DKT) parcellation atlas, we extracted the global SUVR value as the cortical volume-weighted average of the following cortical regions of interest (ROI): frontal, anterior/posterior cingulate, parietal, and lateral temporal cortices. These ROIs are similar to previous studies using FBB PET for measurement of Aβ deposition, but the occipital ROI was excluded in our study because this ROI shows low Aβ load in AD-related changes [15]. We evaluated the entire frontal lobe including but not restricted to the BBB opening site. Specifically, the frontal ROI included the superior frontal, middle frontal, inferior frontal, and orbitofrontal cortices. We then calculated the SUVR of the frontal ROI to other cortical regions including the lateral temporal, lateral parietal, and anterior/posterior cingulate lobes. The lateral temporal ROI covers the middle temporal lobe and the superior temporal lobe. The parietal ROI covers the supramarginal gyrus, superior parietal lobe, precuneus, and inferior parietal lobe.

Changes in neuropsychological test scores and neuropsychiatric symptoms

All study participants underwent a detailed neuropsychological evaluation using the Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery [16] on Visit 1 and Visit 8. Standardized z scores were available for all scorable tests based on age- and education-matched norms. Among the scorable tests, we included the digit span backward test for the attention domain; the Korean version of the Boston Naming Test for the language domain; the copying item of the Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure Test (RCFT) for the visuospatial domain; 20-min delayed recall item of the RCFT and Seoul Verbal Learning Test for the memory domain; and the phonemic Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT), semantic COWAT, and the Stroop color reading test for the frontal/executive domain. Additionally, general cognition and daily functioning were assessed using the K-MMSE, Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR), CDR Sum of Boxes (CDR-SOB), and Korean Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (K-IADL) [17]. K-MMSE scores were additionally assessed at two weeks after the second procedure (Visit 7).

We also assessed patient’s neuropsychiatric symptoms from caregivers using the CGA-NPI [18] at Visit 1, Visit 7 and Visit 8. The CGA-NPI evaluated 12 behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia including delusion, hallucinations, agitation/aggression, depression/dysphoria, anxiety, elation/euphoria, apathy/indifference, disinhibition, irritability/lability, aberrant motor behavior, sleep/nighttime behavior disorders, and appetite/eating change. Each of the symptoms was retrospectively rated for the four weeks prior to the interview.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses for clinical data were performed with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 25.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Differences in clinical data between pre- and post-MRgFUS were tested using a non-parametric paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Participants

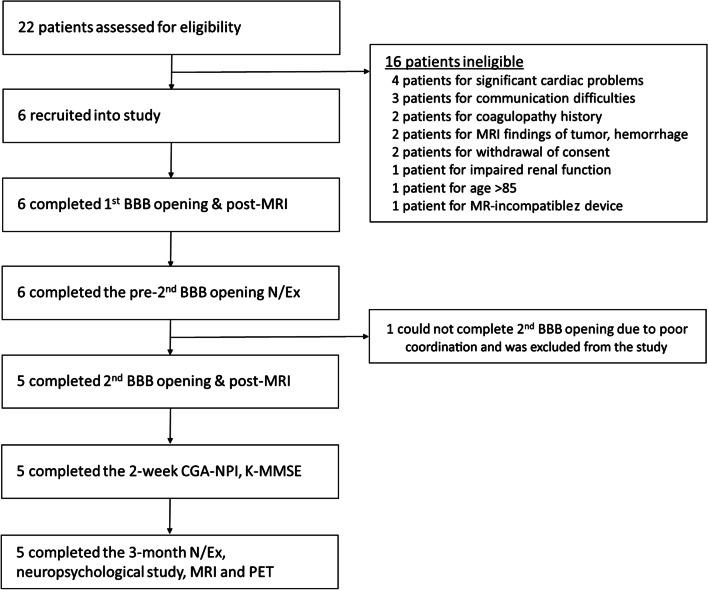

We enrolled five female and one male patients between August 2020 and September 2020. Five patients completed the two consecutive BBB opening procedures. One patient did not complete the second BBB opening procedure due to poor cooperation during MRI, and thus was excluded from analysis (Fig. 2). Demographics of the five included patients are shown in Table 1. The mean baseline K-MMSE score was 17.4 ± 5.2 and the mean baseline CDR-SOB score was 6.3 ± 3.1. The mean baseline FBB global SUVR was 1.937 ± 0.163.

Fig. 2.

Flow chart of the study. BBB, Blood–brain barrier; N/Ex, Neurological examination; MRI, magnetic-resonance imaging; CGA-NPI, Caregiver-Administered Neuropsychiatric inventory; K-MMSE, Korean version of mini-mental state examination; PET, positron emission tomography

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| Age (years) |

Sex | Education (years) |

ApoE4 carrier | Comorbidities | Medications | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 58 | F | 6 | Yes | None | Rivastigmine 18 mg, Choline alfoscerate 800 mg, Lexapro 5 mg |

| Case 2 | 80 | F | 9 | Yes | None | Rivastigmine 18 mg, Choline alfoscerate 800 mg, Lexapro 5 mg |

| Case 3 | 55 | F | 12 | Yes | Myasthenia gravis | Rivastigmine 27 mg, Memantine 5 mg, Lexapro 5 mg, Prednisolone 5 mg, Tacrolimus 3 mg |

| Case 4 | 85 | F | 12 | Yes | Hypertension, osteoporosis | Donepezil 10 mg, Candesartan 16 mg, Amlodipine 5 mg, Calcium 500 mg, Cholecalciferol 1000 IU |

| Case 5 | 75 | M | 12 | No | None | Galantamine 16 mg |

| Mean (SD) | 70.6 (13.5) | 10.2 (2.7) |

SD standard deviation

Primary outcome

The five participants were all tolerable during procedures. No adverse events occurred during the entire study period, including in the case of the excluded sixth patient. Neither systemic nor neurological worsening was reported. Radiologically, there was no brain edema, overt cerebral hemorrhage or infarction during and after the study.

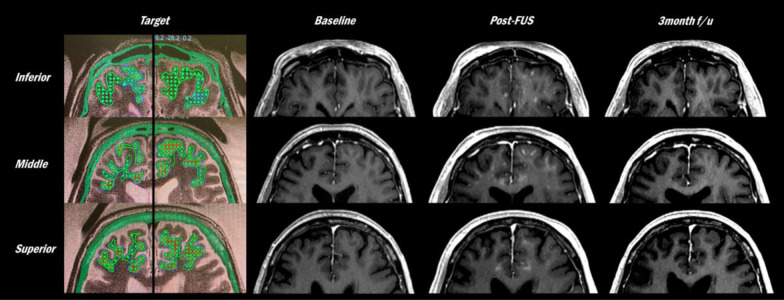

We targeted a mean volume of 21.1 ± 2.7 cm3 in the bilateral frontal lobes (Table 2). Immediate post-procedure gadolinium-enhanced MRI scans showed that 95.7% ± 9.4% of the target was well enhanced (Fig. 3). MRI scans performed 3 months after the second procedure showed no enhancement in this area, indicating the closure of BBB.

Table 2.

Feasibility of blood–brain barrier (BBB) opening as assessed by post-procedure MRI

| Volume (cm3)* | Ratio of BBB opening to target (%)† | |

|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 17.7 | 78.9 |

| Case 2 | 20.0 | 100 |

| Case 3 | 20.6 | 100 |

| Case 4 | 22.6 | 97.6 |

| Case 5 | 24.7 | 100 |

| Mean (SD) | 21.1 (2.7) | 95.7 (9.4) |

*An average volume of two sessions of BBB opening

†An average ratio of BBB opening area to target

Fig. 3.

The targets and MRI demonstration of BBB opening and closure in Patient 3. Immediately post-FUS gadolinium-enhanced T1 MRI showed that parenchyme at target was well enhanced, indicating the successful BBB opening. Afterwards, this area did not show enhancement in MRI at 3 months post-procedure, indicating that the BBB was temporarily opened and closed

Secondary outcome

Reduction in Aβ deposition

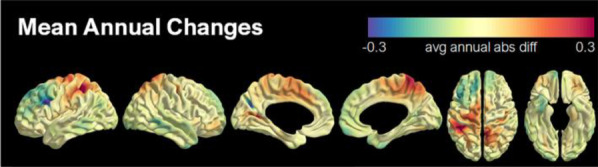

The frontal-to-other brain region FBB SUVR was significantly decreased at Visit 8 compared to Visit 1 (− 1.6%, 0.986 ± 0.065 vs 1.002 ± 0.063, P = 0.043) (Table 3). When the follow-up period of PET was annualized, the mean annualized changes in the global FBB SUVR for the five participants showed the greatest decline in the frontal lobe (Fig. 4, Additional file 1: Fig. S1).

Table 3.

Global and regional 18F-Florbetaben SUVR

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Mean (SD) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit 1 | Visit 8 | Visit 1 | Visit 8 | Visit 1 | Visit 8 | Visit 1 | Visit 8 | Visit 1 | Visit 8 | Visit 1 | Visit 8 | P value | |

| Global SUVR | 2.172 | 2.277 (+ 4.8%) | 1.876 | 1.901 (+ 1.3%) | 1.955 | 1.972 (+ 0.9%) | 1.722 | 1.648 (− 4.3%) | 1.959 | 1.941 (− 0.9%) | 1.937 (0.163) |

1.948 (0.224) (+ 0.6%) |

0.686 |

| Frontal SUVR | 2.211 | 2.287 (+ 3.4%) | 1.803 | 1.815 (+ 0.6%) | 1.904 | 1.913 (+ 0.5%) | 1.808 | 1.728 (− 4.4%) | 1.955 | 1.896 (− 3.0%) | 1.936 (0.167) |

1.928 (0.214) (− 0.4%) |

0.893 |

| Frontal/Other SUVR | 1.034 | 1.008 (− 2.5%) | 0.935 | 0.925 (− 1.1%) | 0.953 | 0.946 (− 0.7%) | 1.091 | 1.089 (− 0.2%) | 0.996 | 0.963 (− 3.3%) | 1.002 (0.063) |

0.986 (0.065) (− 1.6%) |

0.043 |

Wilcoxon signed rank test was used for comparing Visit 1 (baseline) and Visit 8 (3 months post-FUS)

SUVR standardized uptake value ratio

Fig. 4.

Mean annual changes in the 18F-Florbetaben uptake after treatment. The mean annual changes in the 18F-Florbetaben SUVR of five participants after treatment. The colors illustrate the average value of absolute annual differences for the 18F-Florbetaben SUVR between pre and post-treatment. SUVR, Standardized uptake value ratio

Changes in neuropsychological test scores and neuropsychiatric symptoms

In neuropsychological test scores, K-IADL, and other tests performed at Visit 1 and Visit 8, there was no significant difference between visits. There were also no significant differences in K-MMSE score between Visit 1, Visit 7, and Visit 8 (Visit 1 vs Visit 7, 17.4 ± 5.2 vs 17.0 ± 5.7, P = 0.58; Visit 1 vs Visit 8, 17.4 ± 5.2 vs 16.6 ± 5.1, P = 0.69). For neuropsychiatric symptoms, the total CGA-NPI score at Visit 7 was significantly decreased compared to that at Visit 1 (2.2 ± 3.0 vs. 8.0 ± 6.0, P = 0.042). However, the total CGA-NPI score at Visit 8 did not differ significantly from that at Visit 1 (5.2 ± 5.8 vs 8.0 ± 6.0, P = 0.89) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Neuropsychological test scores and neuropsychiatric symptom test scores

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Mean (SD) | P value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit 1 | Visit 8 | Visit 1 | Visit 8 | Visit 1 | Visit 8 | Visit 1 | Visit 8 | Visit 1 | Visit 8 | Visit 1 | Visit 8 | ||

| Neuropsychological test score | |||||||||||||

| Digit span backward | − 4.14 | − 4.14 | 0.53 | 0.53 | − 0.35 | − 1.23 | − 1.98 | − 0.60 | − 1.00 | − 0.88 | − 1.39 (1.79) | − 1.26 (1.74) | 0.59 |

| K-BNT | − 3.38 | − 3.84 | − 0.81 | − 0.68 | − 2.80 | − 2.59 | − 1.61 | − 0.81 | − 1.32 | − 1.94 | − 1.98 (1.07) | − 1.97 (1.31) | 0.89 |

| RCFT copy | − 7.20 | − 7.48 | − 1.88 | − 2.00 | − 9.14 | − 9.37 | 0.93 | 1.00 | − 1.23 | − 0.94 | − 3.70 (4.26) | − 3.76 (4.44) | 0.69 |

| SVLT delayed recall | − 2.97 | − 2.97 | − 2.30 | − 2.30 | − 3.40 | − 3.40 | − 1.42 | − 1.63 | − 2.74 | − 2.51 | − 2.57 (0.75) | − 2.56 (0.67) | 0.66 |

| RCFT delayed recall | − 2.34 | − 2.34 | − 2.07 | − 2.07 | − 3.08 | − 2.91 | − 1.23 | − 0.96 | − 2.54 | − 2.36 | − 2.25 (0.68) | − 2.13 (0.72) | 0.11 |

| COWAT semantic | − 2.99 | − 3.21 | − 0.17 | − 2.08 | − 2.56 | − 2.32 | − 1.91 | − 1.40 | − 2.08 | − 2.65 | − 1.94 (1.08) | − 2.33 (0.67) | 0.50 |

| COWAT phonemic | − 2.53 | − 2.53 | − 0.09 | − 0.82 | − 1.39 | − 1.06 | − 1.03 | − 0.15 | − 0.69 | − 2.09 | − 1.15 (0.91) | − 1.33 (0.97) | 0.72 |

| Stroop color reading | − 4.89 | − 4.77 | − 0.57 | − 1.58 | − 4.56 | − 4.43 | − 0.54 | − 0.42 | − 2.77 | − 3.75 | − 2.67 (2.09) | − 2.99 (1.90) | 0.68 |

| CDR | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1.0 (0.6) | 1.1 (0.55) | 0.32 |

| CDR-SOB | 10 | 10 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 9 | 9 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 6 | 6.3 (3.1) | 6.8 (2.7) | 0.32 |

| K-IADL | 1.67 | 1.78 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 1.33 | 1.21 (0.58) | 1.34 (0.53) | 0.29 |

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Mean (SD) | P value* | P value† | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-MMSE | CGA-NPI | K-MMSE | CGA-NPI | K-MMSE | CGA-NPI | K-MMSE | CGA-NPI | K-MMSE | CGA-NPI | K-MMSE | CGA-NPI | K-MMSE | CGA-NPI | K-MMSE | CGA-NPI | |

| K-MMSE and CGA-NPI score | ||||||||||||||||

| Visit 1 | 9 | 9 | 22 | 16 | 16 | 11 | 21 | 2 | 19 | 2 | 17.4 (5.2) | 8.0 (6.0) | ||||

| Visit7 (post-FUS) | 8 | 3 | 20 | 1 | 16 | 7 | 23 | 0 | 18 | 0 | 17.0 (5.7) | 2.2 (3.0) | 0 .58 | 0.042 | ||

| Visit8 (3 months post-FUS ) | 10 | 7 | 18 | 0 | 19 | 14 | 23 | 9 | 13 | 5 | 16.6 (5.1) | 5.2 (5.8) | 0.69 | 0.89 | ||

Wilcoxon signed rank tests were used to compare the difference between the neuropsychological test z scores, CDR, CDR-SOB, K-IADL, K-MMSE and CGA-NPI of Visit 1 and Visit 8. Also, we compared the K-MMSE and CGA-NPI scores of Visit 1 and Visit 7 with same test. P < 0.05 was considered significant. Visit 1: baseline. Visit 7: 2 weeks post-FUS. Visit 8: 3 months post-FUS

CDR clinical dementia rating scale, CDR-SOB CDR sum of boxes, CGA-NPI caregiver-administrated neuropsychiatric inventory, COWAT controlled oral word association test, K-BNT Korean version of the Boston naming test, K-IADL Korean instrumental activities of daily living, Rey-Osterrieth complex figure Test, K-MMSE Korean version of mini-mental state examination, SD standard deviation, SVLT Seoul verbal learning test

*P value: Comparison between Visit 1 and Visit 7

†P value: Comparison between Visit 1 and Visit 8

Discussion

In this study, we tested the safety and feasibility of extensive BBB opening targeting the bilateral frontal lobes in AD patients. The major findings were: (1) repeated extensive BBB opening was safe and feasible with no serious side effects; (2) extensive BBB opening induced a decrease in Aβ accumulation in the frontal lobe targeted; and (3) neuropsychiatric symptoms were transiently relieved after BBB opening. Our results highlight the safety, feasibility, and possible efficacy of extensive BBB opening.

Previous human trials of BBB opening with MRgFUS have targeted a relatively small area: approximately 1 cm3 frontal BBB opening in AD patients [9], a 2–3 cm3 hippocampal BBB opening in AD patients [10], 3.5 cm3 BBB opening in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients [19] and 5–6 cm3 BBB opening in glioblastoma multiforme patients [20]. Our study is the first human trial of extensive BBB opening targeting an average volume of 21.1 cm3, which achieved BBB opening without any adverse events. The participants tolerated the procedures well and experienced no clinical or radiological side effects throughout the study. Moreover, despite the fact that cerebral vasculature of AD patients is fragile and vulnerable [21, 22], extensive BBB opening is tolerable, safe and reproducible in moderate-to-severe AD patients.

Another important point of our study was the relative Aβ decrease in the frontal lobe in which the BBB was opened. Previous preclinical studies have shown that Aβ burden is reduced by scanning ultrasound [23] or FUS alone in AD models [5]. However, previous human trials have resulted in divergent results. In the study of Lipsman et al., BBB opening at the white matter of frontal lobe did not result in a change in Aβ deposition one week after the BBB opening [9]. On contrary, in the study of D’Haese et al., hippocampal BBB opening induced a relative Aβ reduction in the BBB-opening area on PET one week after the BBB opening [11]. Here our results showed the Aβ-reducing effect of BBB opening in humans.

The course of change of Aβ deposition induced by BBB opening is not yet known. In our study, unlike the previous two studies, PET was performed three months after the last procedure due to regulations in our country which restrict the interval and frequency of use of PET isotopes. Our results showed Aβ decrease even at 3 months after BBB opening procedure. It is not clear whether the Aβ decrease seen in our study is the maintenance state of Aβ decrease caused by the BBB opening or the relative decrease state seen in the process of re-accumulation after Aβ reduction. However, it is meaningful to confirm that relative Aβ decrease is seen even at 3 months after the procedure in circumstance where the changes after BBB opening are not well known in AD patients.

In this study, there was no change in the K-MMSE and comprehensive neuropsychological test scores. However, there was a transient improvement in neuropsychiatric symptoms after extensive frontal BBB opening. Although there is currently no placebo-controlled trial assessing the CGA-NPI score in AD patients, the placebo-controlled trials using NPI score, which is highly correlated with the CGA-NPI score and has same scoring system as CGA-NPI, have shown that the maximal placebo response to neuropsychiatric symptoms in AD reaches at week 4 with an expected reduction of NPI score for 1.2 [24]. In our study, however, as the change in CGA-NPI score was 5.8 at Visit 7 (2 weeks after second BBB opening), which was greater than the previously expected placebo effect, it can be considered that there is a real transient improvement effect from BBB opening. Considering that the neuropsychiatric symptoms in AD are associated with the structural and metabolic changes in the frontal cortex and the disruption of the fronto-temporal-subcortical network [25], extensive BBB opening in the frontal cortex may be associated with improvement of the symptoms. The improvement found in our study, which was not seen in other studies, may be attributed to the BBB opening area, which was several times larger than that of other studies, or the location of BBB opening, as the frontal lobe has many connections with other areas.

Currently, the exact mechanisms underlying the temporary or sustained improvement after BBB opening remain unknown. Besides reduction of Aβ [26], several other mechanisms have been suggested in previous preclinical studies, including inflammation-induced neurogenesis [27], delivery of endogenous antibodies [28], and modulation of the glymphatic [29] or cerebrospinal fluid clearance system [27]. The neuromodulatory effect may also be involved. A previous functional MRI study has shown that MRgFUS targeting the right frontal lobe can induce transient changes in the frontoparietal network [30].

However, in this study, the improvements in neuropsychiatric symptoms did not persist till three months after the second procedure. Although the closing timeline varies widely across parameters, FUS systems, and detection approaches, the BBB opening itself is temporary and usually restored after 4 h [31], and the duration of the effect of BBB opening in AD models is reported from 3 days to 2 weeks [32–34] in preclinical studies. However, how long the effect of BBB opening lasts in humans has not been studied. Previous clinical studies were conducted at intervals of 2 weeks or 1 month, whereas our study was conducted at 3-month intervals, which were longer than previously used. As a result, we were able to confirm that the effect of BBB opening could last for 2–4 weeks, after which the symptoms worsen again.

Although the clinical improvements did not last for several months in most patients of our study, this study demonstrated that BBB opening alone can improve symptoms in humans, consistent with previous preclinical studies. Future studies with repeated extensive BBB opening combined with adjuvant therapeutics, such as stem cell therapy, neurotrophic factors, or immunomodulatory drugs may show potentials, based on preclinical evidence that the repetitive procedure of FUS in combination with antibodies or other drugs results in better outcomes than FUS treatment alone [5, 6, 32]. Also, considering that several therapeutics for AD have failed due to the limited BBB permeability [35], MRgFUS, which is demonstrated to be safe, can be used to overcome the problem of limited BBB permeability.

This study has several limitations. First, our study had a small sample size. Although this study demonstrated clinical and radiographical safety of and possible clinical benefits from the MRgFUS-induced extensive BBB opening, these results are limited in their generalizability as such. In addition, the participants in our study were patients with moderate to severe AD and most of them were APOE4 carriers (four of the five). It is necessary to interpret our results cautiously. Second, this study did not demonstrate objective cognitive improvements. The transient clinical benefits induced by extensive BBB opening could not be excluded as the neuropsychological evaluation was not performed at two weeks after the second MRgFUS procedure unlike CGA-NPI. The lack of cognitive improvements may also be related to the small sample size in this study and the study design. The open-label design of the current study prevented the inclusion of an AD control group without a MRgFUS procedure due to ethical concerns. As cognitive function deteriorates with the progression of AD, this could have limited the power of our study. In future studies, an AD control group matched for demographic factors and disease severity should be included. Third, there was no placebo-controlled arm in this study, so we cannot exclude the contribution of placebo effect to the transient improvement of CGA-NPI score. Although according to previous studies the placebo effect might not be the only factor in the transient improvement of neuropsychiatric symptoms in this study, a study with a placebo arm is also needed in the future. Fourth, the PET analysis in this study analyzed SUVR changes in the entire frontal lobe rather than specifically analyzing the volumes of brain regions subjected to BBB opening.

Conclusions

Repeated and extensive BBB opening in the frontal lobe is safe and feasible, and results in decreased FBB SUVR and temporary improvement in related symptoms. As BBB opening is a safe procedure even for moderate-to-severe AD, in future studies it may be applied to AD patients without limitations on the disease severity.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Table S1: Inclusion and exclusion criteria. Fig. S1: Individual longitudinal changes in 18F-Florbetaben uptake after treatment.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Eo Su Kim, MD and Eun Jung Kweon, RN, for help in recruiting the patients. We would also like to thank Itay Rachimilevitch, Gabriella Toltsis, Rafi De Picciotto and Eyal Zadicario from InSightec for their great technical assistance in this study.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- Aβ

Amyloid-beta

- BBB

Blood brain barrier

- CGA-NPI

Caregiver-Administered Neuropsychiatric Inventory

- CDR

Clinical Dementia Rating

- CDR-SOB

CDR Sum of Boxes

- COWAT

Controlled Oral Word Association Test

- FBB

18F-Florbetaben

- FUS

Focused ultrasound

- IADL

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MRgFUS

Magnetic resonance-guided FUS

- MMSE

Mini-Mental State Examination

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- RCFT

Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure Test

- SUVR

Standardized uptake value ratio

Authors' contributions

BSY and JWC designed the study. SHP, KB, WSC, BSY and JWC recruited patients. KB, BSY and JWC provided assessments and follow-up. JWC performed the procedure. SHP, WSC and SJ analyzed the imaging data. SHP and KB drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final manuscript before submission. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the Brain Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korean Ministry of Science, ICT, and Future Planning, a Government Department (2016M3C7A1914123). The sponsor of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to personal information of the patient, but available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethic approval and consent to participate

Study approval by Institutional Review Board of Severance Hospital was obtained before the study initiation (No. 1-2019-0095). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and their primary caregivers.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

So Hee Park and Kyoungwon Baik have contributed equally to the manuscript

Contributor Information

Byoung Seok Ye, Email: romel79@gmail.com.

Jin Woo Chang, Email: jchang@yuhs.ac.

References

- 1.Duyckaerts C, Delatour B, Potier M-C. Classification and basic pathology of Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118(1):5–36. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0532-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297(5580):353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aisen P, Cummings J, Doody R, Kramer L, Salloway S, Selkoe D, et al. The future of anti-amyloid trials. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2020:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Chen KT, Wei KC, Liu HL. Theranostic strategy of focused ultrasound induced blood–brain barrier opening for CNS disease treatment. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:86. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burgess A, Dubey S, Yeung S, Hough O, Eterman N, Aubert I, et al. Alzheimer disease in a mouse model: MR imaging-guided focused ultrasound targeted to the hippocampus opens the blood–brain barrier and improves pathologic abnormalities and behavior. Radiology. 2014;273(3):736–745. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14140245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsu PH, Lin YT, Chung YH, Lin KJ, Yang LY, Yen TC, et al. Focused ultrasound-induced blood–brain barrier opening enhances GSK-3 inhibitor delivery for amyloid-beta plaque reduction. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):12882. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31071-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karakatsani ME, Kugelman T, Ji R, Murillo M, Wang S, Niimi Y, et al. Unilateral focused ultrasound-induced blood–brain barrier opening reduces phosphorylated Tau from the rTg4510 mouse model. Theranostics. 2019;9(18):5396–5411. doi: 10.7150/thno.28717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shin J, Kong C, Lee J, Choi BY, Sim J, Koh CS, et al. Focused ultrasound-induced blood–brain barrier opening improves adult hippocampal neurogenesis and cognitive function in a cholinergic degeneration dementia rat model. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2019;11(1):110. doi: 10.1186/s13195-019-0569-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lipsman N, Meng Y, Bethune AJ, Huang Y, Lam B, Masellis M, et al. Blood–brain barrier opening in Alzheimer's disease using MR-guided focused ultrasound. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):2336. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04529-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rezai AR, Ranjan M, D'Haese PF, Haut MW, Carpenter J, Najib U, et al. Noninvasive hippocampal blood–brain barrier opening in Alzheimer's disease with focused ultrasound. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(17):9180–9182. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2002571117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Haese PF, Ranjan M, Song A, Haut MW, Carpenter J, Dieb G, et al. Beta-amyloid plaque reduction in the hippocampus after focused ultrasound-induced blood–brain barrier opening in Alzheimer's disease. Front Hum Neurosci. 2020;14:593672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR, Jr, Kawas CH, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Villain N, Chételat G, Grassiot B, Bourgeat P, Jones G, Ellis KA, et al. Regional dynamics of amyloid-β deposition in healthy elderly, mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: a voxelwise PiB–PET longitudinal study. Brain. 2012;135(7):2126–2139. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Funck T, Paquette C, Evans A, Thiel A. Surface-based partial-volume correction for high-resolution PET. Neuroimage. 2014;102:674–687. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sabri O, Sabbagh MN, Seibyl J, Barthel H, Akatsu H, Ouchi Y, et al. Florbetaben PET imaging to detect amyloid beta plaques in Alzheimer's disease: phase 3 study. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(8):964–974. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang Y, Na D, Hahn S. Seoul neuropsychological screening battery. Incheon: Human Brain Research & Consulting Co.; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chin J, Park J, Yang SJ, Yeom J, Ahn Y, Baek MJ, et al. Re-standardization of the Korean-Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (K-IADL): clinical usefulness for various neurodegenerative diseases. Dement Neurocogn Disord. 2018;17(1):11–22. doi: 10.12779/dnd.2018.17.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang SJ, Choi SH, Lee BH, Jeong Y, Hahm DS, Han IW, et al. Caregiver-administered neuropsychiatric inventory (CGA-NPI) J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2004;17(1):32–5. doi: 10.1177/089198873258818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abrahao A, Meng Y, Llinas M, Huang Y, Hamani C, Mainprize T, et al. First-in-human trial of blood–brain barrier opening in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis using MR-guided focused ultrasound. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):4373. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12426-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park SH, Kim MJ, Jung HH, Chang WS, Choi HS, Rachmilevitch I, et al. Safety and feasibility of multiple blood-brain barrier disruptions for the treatment of glioblastoma in patients undergoing standard adjuvant chemotherapy. J Neurosurg. 2020:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Waziry R, Chibnik LB, Bos D, Ikram MK, Hofman A. Risk of hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke in patients with Alzheimer disease: a synthesis of the literature. Neurology. 2020;94(6):265–272. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buee L, Hof PR, Bouras C, Delacourte A, Perl DP, Morrison JH, et al. Pathological alterations of the cerebral microvasculature in Alzheimer's disease and related dementing disorders. Acta Neuropathol. 1994;87(5):469–480. doi: 10.1007/BF00294173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leinenga G, Gotz J. Scanning ultrasound removes amyloid-beta and restores memory in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(278):278ra33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Zhang N, Lv Y, Li H, Chen J, Li Y, Yin F, et al. Quantifying placebo responses in clinical evaluation of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;75(4):497–509. doi: 10.1007/s00228-018-02620-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boublay N, Schott AM, Krolak-Salmon P. Neuroimaging correlates of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease: a review of 20 years of research. Eur J Neurol. 2016;23(10):1500–1509. doi: 10.1111/ene.13076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sevigny J, Chiao P, Bussiere T, Weinreb PH, Williams L, Maier M, et al. The antibody aducanumab reduces Abeta plaques in Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2016;537(7618):50–56. doi: 10.1038/nature19323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Todd N, Angolano C, Ferran C, Devor A, Borsook D, McDannold N. Secondary effects on brain physiology caused by focused ultrasound-mediated disruption of the blood–brain barrier. J Control Release. 2020;324:450–459. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.05.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jordão JF, Thévenot E, Markham-Coultes K, Scarcelli T, Weng YQ, Xhima K, et al. Amyloid-β plaque reduction, endogenous antibody delivery and glial activation by brain-targeted, transcranial focused ultrasound. Exp Neurol. 2013;248:16–29. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meng Y, Abrahao A, Heyn CC, Bethune AJ, Huang Y, Pople CB, et al. Glymphatics visualization after focused ultrasound-induced blood–brain barrier opening in humans. Ann Neurol. 2019;86(6):975–980. doi: 10.1002/ana.25604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meng Y, MacIntosh BJ, Shirzadi Z, Kiss A, Bethune A, Heyn C, et al. Resting state functional connectivity changes after MR-guided focused ultrasound mediated blood–brain barrier opening in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Neuroimage. 2019;200:275–280. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheikov N, McDannold N, Sharma S, Hynynen K. Effect of focused ultrasound applied with an ultrasound contrast agent on the tight junctional integrity of the brain microvascular endothelium. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2008;34(7):1093–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alecou T, Giannakou M, Damianou C. Amyloid beta plaque reduction with antibodies crossing the blood–brain barrier, which was opened in 3 sessions of focused ultrasound in a rabbit model. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36(11):2257–2270. doi: 10.1002/jum.14256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jordao JF, Thevenot E, Markham-Coultes K, Scarcelli T, Weng YQ, Xhima K, et al. Amyloid-beta plaque reduction, endogenous antibody delivery and glial activation by brain-targeted, transcranial focused ultrasound. Exp Neurol. 2013;248:16–29. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poon CT, Shah K, Lin C, Tse R, Kim KK, Mooney S, et al. Time course of focused ultrasound effects on beta-amyloid plaque pathology in the TgCRND8 mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):14061. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-32250-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pardridge WM. Treatment of Alzheimer's disease and blood–brain barrier drug delivery. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2020;13(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Table S1: Inclusion and exclusion criteria. Fig. S1: Individual longitudinal changes in 18F-Florbetaben uptake after treatment.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to personal information of the patient, but available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.