Abstract

Aryl-substituted pyridine(diimine) iron complexes promote the catalytic [2+2] cycloadditions of alkenes and dienes to form vinylcyclobutanes as well as the oligomerization of butadiene to generate divinyl(oligocyclobutane), a microstructure of poly(butadiene) that is chemically recyclable. A systematic study on a series of iron butadiene complexes as well as their ruthenium congeners has provided insights into the essential features of the catalyst that promotes these cycloaddition reactions. Structural and computational studies on iron butadiene complexes identified that the structural rigidity of the tridentate pincer enables rare s-trans diene coordination. This geometry, in turn, promotes dissociation of one of the alkene arms of the diene, opening a coordination site for the incoming substrate to engage in oxidative cyclization. Studies on ruthenium congeners has established that this step occurs without redox involvement of the pyridine(diimine) chelate. Cyclobutane formation occurs from a metallacyclic intermediate by reversible C(sp3)–C(sp3) reductive coupling. A series of labeling experiments with pyridine(diimine) iron and ruthenium complexes support the favorability of accessing the +3 oxidation state to trigger C(sp3)–C(sp3) reductive elimination, involving spin crossover from S = 0 to S = 1. The high density of states of iron and the redox-active pyridine(diimine) ligand facilitate this reactivity under thermal conditions. For the ruthenium congener, the pyridine(diimine) remains redox innocent and irradiation with blue light was required to promote the analogous reactivity. These structure-activity relationships highlight important design principles for the development of next generation catalysts for these cycloaddition reactions as well as to promote chemical recycling of cycloaddition polymers.

Keywords: [2+2] cycloaddition, depolymerization, iron, redox active ligands, cyclobutanes

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Cyclobutanes are a rapidly expanding structural subunit in molecular design due in part to the unique properties associated with their conformations.1–7 Incorporation of multiple cyclobutyl units into polymers has been shown to confer structural rigidity without imparting impact or thermal instability, as demonstrated with copolyesters with cyclobutanediols8–10 and homopolymers of 1,2- and 1,3-enchained cyclobutanes.11–13 Polymeric cyclobutanes also have chain packing structures that lend to remarkable macromolecular properties, as exemplified in the highly dense packing of lipid ladderanes.14–15

Recently, our laboratory has reported the pyridine(diimine) (PDI) iron-catalyzed polymerization of butadiene by successive [2+2] cyclizations to generate (1,n’-divinyl)oligocyclobutane (DVOCB), the first new homopolymer of butadiene synthesized in over one hundred years (Figure 1A).16 Comprised of 1,3-enchained cyclobutyl units terminated with vinyl groups, this homopolymer also exhibits high crystallinity and thermal stability even at low molecular weights, while also exhibiting liquid crystalline behavior above its melting temperature. In addition, this polymer can also be converted back to butadiene monomer by [(PDI)Fe]-catalyzed retro-[2+2] cyclization originating from strain-release activation of the vinylcyclobutane units within the chain, establishing a rare example of the chemical recycling of a polyolefin to pristine hydrocarbon monomer. The polymerization and retro-[2+2] cyclization sequences have proven unique to the [(PDI)Fe] family of catalysts, perhaps accounting for the elusive synthesis of (1,n’-divinyl)oligocyclobutane.

Figure 1.

[(PDI)Fe]-catalyzed intermolecular [2+2] cycloaddition of feedstock dienes and olefins and exploring the features of the iron catalysts that enable the unique reactivity.

Understanding the features of the [(PDI)Fe] catalysts that give rise to the unusual cycloaddition reactivity with butadiene to enable the synthesis of chemically recyclable DVOCB is essential for design of next generation catalysts with improved performance. Direct study of the iron catalyst during the oligomerization reaction is experimentally challenging given that the reactions are conducted in neat butadiene monomer at slightly elevated temperatures. A related reaction is the iron-catalyzed intermolecular [2+2] cycloaddition of dienes and alkenes to form vinylcyclobutanes (Figure 1B). Like the synthesis of DVOCB, [(PDI)Fe] are unique catalysts for promoting these transformations selectively, in high yields and under mild conditions.17–19 While previous studies have expanded the understanding of the kinetics and scope of [2+2] cycloaddition reactions,18, 20–21 there are limited inisghts into what features of the catalyst promote this unique reactivity. This lack of precatalyst structure-activity relationships hinders the design of next generation of precatalysts that exhibit higher activity for the production of vinylcyclobutane and (1,n’-divinyl)oligocyclobutane.

Several characteristics of [(PDI)Fe] complexes may be responsible for the unique chemoselectivity observed in intermolecular cycloaddition reactions (Figure 1C). The ground state of [(PDI)Fe] conjugated diene complexes features an unusual s-trans geometry18,22,23 raising the question if this configuration is required for subsequent oxidative cyclization and metallocycle formation. This geometry has previously been implicated by Erker and coworkers in the stoichiometric oxidative cyclization reactivity between coordinated butadiene and ethylene in zirconocene and hafnocene complexes24–26 but translation on to catalytic chemistry has not been demonstrated. If the s-trans diene geometry is a prerequisite for cycloaddition reactivity, it is unknown how to rationally enforce this geometry at a metal center.

In addition, the features of the iron catalyst that promote C–C bond formation in the oxidative cyclization step and in the C(sp3)–C(sp3) reductive elimination event have not been identified. In the iron-catalyzed cycloaddition between ethylene and butadiene, an intermediate metallocycle was observed and crystallographically characterized, demonstrating the accessibility of the S = 0 spin surface.17 The redox activity of the pyridine(diimine) raises the possibiility of an electron transfer event, reducing the chelate by one electron, oxidizing the iron and engaging fundamental steps of the catalytic cycle on an S = 1 surface.20, 27–28 Computational studies by Chen and coworkers reported the feasibility of spin surface changes during bond-forming events in intermolecular diene-alkene [2+2] cycloaddition,29 but there has been no experimental validation of these predictions. While challenging to experimentally support, the possibility or requirement for spin crossover events derived from ligand redox activity to enable steps in the catalytic cycle has far reaching implications for the design of next-generation precatalysts for the production of vinylcyclobutane and other feedstock olefin-derived cyclobutanes.

Here, we describe a systematic and comprehensive evaluation of features of the [(PDI)Fe] and related catalysts that enable the intermolecular [2+2] cyclization of feedstock dienes and olefins. A series of new iron and ruthenium compounds was synthesized to probe each of the individual features hypothesized as key for promoting cyclization reactivity. The results of this approach provide mechanistic insight and ultimately guidelines for the development of more active pincer-ligated iron for the synthesis of cyclobutane-containing compounds.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Factors Controlling Diene Disposition at Iron.

Our studies commenced with exploring the origins of the unusual trans coordination geometry of conjugated dienes in pyridine(diimine) iron complexes and its relevance to oxidative cyclization. To assess how rare trans conjugated diene coordination is in organometallic chemistry, an analysis of the structures in the Cambridge Structural Database30 was conducted. The search revealed that, of the 328 metal complexes containing conjugated dienes, only 20 (~6%) have an s-trans configuration (see Supporting Information for additional details). Of the 118 iron complexes deposited, only 3 (~3%) are trans and all three are pyridine(diimine) examples reported by our group (Figure 2).18,22,23 By contrast, 81% of the iron conjugated diene compounds have s-cis dienes ligated to tricarbonyl derivatives with a pentacoordinate “three-legged piano stool” configuration (Figure 2). The iron tricarbonyl butadiene complex, (CO)3Fe(s-cis-η-C4H6), is isolobal with the pyridine(diimine) derivatives31 yet X-ray diffraction has established cis rather than trans diene coordination,32 suggesting metal coordination geometry influences diene stereochemistry and potentially reactivity.

Figure 2.

Analysis of diene coordination geometry with crystallographically characterized iron-diene complexes in the Cambridge Structural Database.

To elucidate the origins of trans-butadiene coordination, computational studies were conducted on (CO)3Fe(η4-C4H6) where the geometry of the [Fe(CO)3] fragment was systematically varied. One starting point is the observed experimental extreme where the three carbonyl ligands adopt a piano stool geometry. The other mimics the coordination environment of the tridentate pyridine(diimine) pincer where the three carbonyl ligands are contained in a plane with the iron.

To quantify the geometric progression between the piano stool and planar [Fe(CO)3] fragments, a Walsh-type diagram was constructed based on DFT-computed energies of various intermediate geometries with both cis and trans coordinated butadiene ligands. Energies were computed with both B3LYP-D3 and BP86-D3 functionals. Ideally, findings from this model would translate on to chelating ligands and allow prediction and rational synthesis of either cis or trans diene complexes. A plane angle was defined as the angle between two separate planes formed by two carbonyl ligands and the iron (Figure 3A). In the three-legged piano stool geometry found in (CO)3Fe(s-cis-η4-C4H6), the plane angle is 90°, whereas in the geometry analogous to that found in the pyridine(diimine) analog, (CO)3Fe(s-trans-η4-C4H6), the plane angle is 180°. Two approaches were assayed in the construction of the Walsh-like diagram: in series of calculations, the plane angle in hypothetical (CO)3Fe(s-trans-η4-C4H6) was systematically reduced from 180° to 90° while maintaining trans-butadiene coordination. Likewise, a second set of calculations was conducted where the plane angle in the piano stool compound was systematically increased from 90° to 180° while maintaining cis butadiene coordination (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Correlation of diene disposition at (CO)3Fe(C4H6) to plane angle. A. Definition of plane angle. B. Continuum of geometries between a plane angle of 90° and 180° for (CO)3Fe(s-cis C4H6) and (CO)3Fe(s-trans C4H6) explored computationally. Plane angles generated using Mercury version 2020.2.0. C. DFT-computed energy (BP86-D3/TZ2P in squares, B3LYP-D3/TZ2P in circles) of (CO)3Fe(s-cis C4H6) (blue) and (CO)3Fe(s-trans C4H6) (red) as a function of plane angle. D. Plane angles of previously reported, crystallographically-characterized (PDI)Fe(s-trans diolefin) complexes.

Plotting the computed energies of the various minimized structures as a function of plane angle established that the energy of the iron complexes containing the s-trans butadiene is relatively invariant with respect to the plane angle. By contrast, the energy of the iron complexes with s-cis butadiene coordination increases steadily with increasing plane angle (Figure 3C). Notably, the energies of the iron complexes with the two butadiene configurations intersect at approximately 155°, a key value for prediction of butadiene geometry at idealized five-coordinate complexes. Complexes with plane angles below 155° are predicted to have s-cis-butadiene ligands while those with plane angles greater than 155° are predicted to be trans. Support for these predictions derives from the observation that the plane angles in pyridine(diimine) iron butadiene complexes are all above 155° and all have trans butadiene ligands (Figure 3D).

To provide experimental support for the plane angle model and its utility for predicting butadiene coordination geometry, additional iron complexes bearing tridentate pincer ligands were targeted. [(PNN)Fe] complexes ((PNN =[N-[2-[[2-(diphenylphosphino)ethyl]imino]-1(2H)-acenaphthylenylidene]-2,6-dimethylbenzenamine) are a redox-active class of compounds pioneered by Carney and Small that are able to polymerize ethylene, with an example of a butadiene derivative reported by our group.33, 34 Likewise, [(PNP)Fe] (PNP = bis(diisopropylphosphino)pyridine) complexes have also been explored as more innocent tridentate chelates to those exhibiting redox activity.35 Stirring a 1:1 diethyl ether:pentane slurry containing either (PNN)FeCl2 or (PNP)FeCl2 with a slight excess of magnesium butadiene at 23 °C generated the corresponding iron butadiene compounds in 53% and 56% yields, respectively (Scheme 1A). Crystallographic characterization of both iron compounds established s-cis coordination of the butadiene ligands where the overall geometry of the complexes is best described as trigonal bipyramidal with the pincers occupying the two equatorial and one axial site. (Scheme 1B). Determination of the plane angles from the structural data revealed a value of 125° and 118° for the PNN and PNP complexes, respectively, well below the 155 ° threshold for s-trans-butadiene coordination.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis, characterization, and catalytic activity of PNP- and PNN-ligated Fe(C4H6) complexes. ORTEPs shown at 30% probability. Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity.

Further examination of the metrical parameters in both complexes provides additional insights into the iron-diene interactions. In (PNP)Fe(s-cis-η4-C4H6), the average Fe–C bond to the axial olefin (C(22)–C(23) = 2.071(3) Å) is longer than the corresponding bond to the olefin in the equatorial plane (C(20)-C(21) = 2.038(3) Å). Likewise, the C–C bond for the axial olefin fragment is slightly longer than the equatorial olefin (1.408(4) Å vs. 1.393(5) Å, respectively), consistent with more backdonation from the iron center to the basal olefin. This slightly increased metallacyclopropane-like character at the basal C-C bond may account for the upfield-shifted resonances for the protons associated with the basal olefin, which appear as three signals from −0.25 to −1.90 ppm in the 1H NMR spectrum (benzene-d6, 25 °C, see Supporting Information for spectra). The solid-state 57Fe Mossbauer parameters for (PNP)Fe(s-cis-η4-C4H6) (δ = 0.38 mm s−1, |ΔEQ| = 1.85 mm s−1) are in good agreement with those of (PDI)Fe(diolefin) complexes (Table 1). For (PNN)Fe(s-cis-η4-C4H6C4H6), the equatorial olefin (C(35)–C(36) = 2.081(3) Å) has an elongated C–C bond compared to that of the axial olefin (C(37)–C(38) = 2.072(3) Å). However, the C–C bond of the basal olefin is, within error, the same length as the axial C–C bond (2.081(3) Å vs. 2.072(3) Å, respectively). Nevertheless, resonances corresponding to the butadiene protons appear upfield of 0.0 ppm in the benzene-d6 1H NMR spectrum (see Supporting Information for spectra), suggesting metal-alkyl type character rather than metal-olefin character. The isomer shift of 0.33 mm s−1 |ΔEQ| = 0.50 mm s−1) is consistent with both (PNP)Fe(s-cis-η4-C4H6) and (PDI)Fe(s-trans-η4-C4H6). The isomer shift of 1.50 mm s−1 more closely resembles that of (PNP)Fe(s-cis-η4-C4H6), which can be attributed to geometric similarities.

Table 1.

Comparative solid-state Mossbauer data (80 K) for pincer-ligated Fe(diolefin) complexes.

| δ (mm s−1) | |ΔEQ| (mm s−1) | |

|---|---|---|

| (PNP)Fe(s-trans-η4-C4H6) | 0.38 | 1.85 |

| (PNN)Fe(s-trans-η4-C4H6) | 0.33 | 1.50 |

| (MePDI)Fe(s-trans-η4-C4H6)ref.18 | 0.38 | 0.50 |

| (MePDI)Fe(s-trans-η4-E-piperylene)ref.18 | 0.38 | 0.78 |

| (iPrPDI)Fe(s-trans-η4-C4H6)ref.23 | 0.38 | 0.38 |

| (iPrPDAI)Fe(s-trans-η4-C4H6)ref.23 | 0.37 | 0.73 |

| (Me(Ph)PDI)Fe(s-trans-η4-C4H6) | 0.40 | 0.77 |

Each of the iron butadiene compounds was evaluated as a potential precatalyst for the [2+2] cycloaddition of butadiene and ethylene using conditions optimized for [(PDI)Fe] catalysts (Scheme 1C). No evidence for vinylcyclobutane formation was observed after 24 hours at 23 °C. Attempts to generate a metallocycle by addition of excess ethylene was also unsuccessful as no conversion was observed after 24 hours at 23 °C. These results support the importance of the trans-coordination of the butadiene ligand for it to engage in oxidative cyclization.

Butadiene cis-trans Isomerization and Substitutional Lability.

While the plane angle is useful for predicting the coordination geometry of a conjugated diene in iron complex with a tridentate pincer, the model is based on structural parameters and does not account for the possibility of fluxional processes that interconvert cis and trans configurations. To experimentally probe this possibility, variable temperature (VT) NMR studies on (MePDI)Fe(s-trans-η4-C4H6) were conducted. No new or perturbed signals for the butadiene ligand were observed by 1H NMR spectroscopy in toluene-d8 from −90 to +90 °C, consistent with no dynamic process on the NMR timescale (Scheme 2A). The signals for the aryl imine resonances coalesce at 60 °C and is consistent with a dynamic process involving rotation of the aryl groups (Scheme 2B). Similar dynamics were observed with related pyridine(diimine) iron butadiene complex with C-imine phenyl substituents, (Me(Ph)PDI)Fe(s-trans-η4-C4H6), that has the propensity to deactivate by η6 coordination of the phenyl groups when coordinatively unsaturated (Scheme 2C).36 Heating a toluene-d8 solution of (MePDI)Fe(s-trans-η4-C4H6) to 80 °C resulted in decomposition but importantly no evidence was obtained for trans to cis isomerization of the butadiene ligand.

Scheme 2.

Variable temperature NMR experiments on the interconversion of s-trans and s-cis C4H6 with [(PDI)Fe] complexes.

While control of the butadiene coordination geometry at iron centers is significant for precatalyst design, the incoming olefin coupling partner must coordinate to the iron for oxidative cyclization to occur. Although the VT NMR data establish that s-cis butadiene is not detectably formed at the [(PDI)Fe] center, it also raises the question of whether the butadiene ever dissociates from the metal during the catalytic reaction.

To assess the lability of the butadiene at [(PDI)Fe], exchange experiments were conducted whereby butadiene-d6 was added to a benzene-d6 solution of (MePDI)Fe(s-trans-η4-C4H6) at room temperature. Monitoring the reaction by 1H and 2H NMR spectroscopies indicated established rapid butadiene exchange with equilibration occurring in under two minutes at 23 °C (Scheme 3A). This experiment establishes a labile butadiene ligand that is confined to an s-trans-geometry when coordinated to iron.

Scheme 3.

Experiments probing the lability and mechanism of butadiene exchange with (MePDI)Fe(s-trans-η4-C4H6).

To distinguish associative versus dissociative diene substitution, the rate of butadiene exchange as a function of concentration was investigated by 1H-1H NMR Exchange Spectroscopy (EXSY). The rate of exchange was measured by incubation of (MePDI)Fe(s-trans-η4-C4H6) with 1–20 equivalents of free butadiene at 23 °C. A plot of kobs versus equivalents of added butadiene (Scheme 3B) indicated little change in the rate of exchange across the range of concentrations studied. These data support a dissociative mechanism likely involving dissociation of one of the alkenes of the coordinated diene, consistent with previous reports on related piperylene couplings (Scheme 3C).18

The variable temperature and exchange NMR studies coupled with the plane angle model detail a complete picture for the origin of trans-butadiene coordination and its impact on reactivity. The geometric features, particularly, the planarity, of the pyridine(diimine) ligand favor trans coordination. The rigidity of the redox-active pincer enables this unusual geometry and is a crucial design feature for [2+2] precatalysts. This in turn enables dissociation of one olefin of the coordinated butadiene opening a site for an incoming olefin or diene for subsequent oxidative cyclization to form the corresponding metallocycle. These findings are consistent with the stoichiometric studies with zirconocene and hafnocene butadiene complexes that undergo oxidative cyclization with ethylene,25 where only the s-trans butadiene isomer undergoes coupling to form the metallacycloheptene.

Factors Determining Oxidative Cyclization Reactivity: Synthesis and Activity of Pyridine(diimine) Ruthenium Congeners.

While both (PNN)Fe(s-cis-η4-C4H6) and (PNP)Fe(s-cis-η4-C4H6) exhibited no activity upon exposure to ethylene under conditions in which (PDI)Fe is active, there are a number of structural and electronic differences between these iron complexes and the active pyridine(diimine)-supported catalysts. A more direct comparison is the ruthenium congener, (MePDI)Ru(s-trans-η4-C4H6), that would offer greater structural similarity but potentially distinct electronic properties as the redox-activity of the pyridine(diimine) may be diminished. Previous work from Berry and coworkers has established that bis-olefin and metallocyclic (PDI)Ru species are best described as closed shell Ru(0) and Ru(II) complexes, respectively, with the PDI ligands exhibiting no redox activity.37,38 Based on this precedent, [(PDI)Ru] bis-olefin complexes were targeted to determine if intermolecular olefin-diene oxidative cyclization is feasible in the absence of PDI participation.

Reduction of (MePDI)RuCl2 with 1.5 equivalents of a slurry of magnesium butadiene in 1:1 pentane:diethyl ether afforded a dark green diamagnetic solid identified as the butadiene complex, (MePDI)Ru(s-trans-η4-C4H6) (Scheme 4A). Characterization by 1H and two-dimensional (2D) NMR spectroscopy support s-trans coordination of butadiene. This was further supported by synthesis and crystallographic characterization of the related piperylene derivative, (MePDI)Ru(s-trans-η4-E-piperylene) (Scheme 4B). The ruthenium piperylene complex is C1 symmetric in benzene-d6 solution, in contrast to the previously reported (MePDI)Fe(s-trans-η4-E-piperylene) complex, which exhibits C2v symmetry due to rapid dynamics of the piperylene at the iron center.18 The lower symmetry observed for (MePDI)Ru(s-trans-η4-E-piperylene) implies stronger coordination to the metal center raising the barrier for the dynamic process. Distortions to the bond lengths of the pyridine(diimine) ligands in solid-state structures of (PDI)Ru37–39 and (PDI)Fe40–42 complexes are established reporters of redox activity. Comparison of the bond lengths of (MePDI)Ru(s-trans-η4-E-piperylene) to reported (PDI)Ru(0) and (PDI)Ru(II) complexes indicate that the diolefin complex is best described as a Ru(0) complex with a neutral PDI ligand (Table 2).

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of A. (MePDI)Ru(s-trans η4-C4H6), and synthesis and crystallographic characterization of B. (MePDI)Ru(s-trans-η4-E-piperylene). ORTEP shown at 30% probability. Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity.

Table 2.

Selected bond distances of crystallographically characterized (PDI)Ru complexes. Bond lengths are given in Å.

| Cimine-Nimine | Cimine-Cpyr | Cpyr-Npyr | Ru-Nimine | Ru-Npyridine | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (MePDI)Ru(s-trans η4-E-piperylene) | 1.342(4) 1.344(4) |

1.417(4) 1.409(4 |

1.391(4) 1.400(4) |

2.077(2) 2.065(2) |

1.930(2) |

| (MePDI)Ru(CO)2ref.37 | 1.334(3) 1.335(3) |

1.422(4) 1.421(4) |

1.398(2) 1.400(3) |

2.062(2) 2.072(2) |

1.9471(19) |

| (MePDI)Ru(C2H2)ref.38 | 1.326(3) 1.332(3) |

1.428(3) 1.425(3) |

1.383(3) 1.387(3) |

2.0572(18) 2.0582(18) |

1.9613(17) |

| (MePDI)Ru(PMe3)2ref.37 | 1.351(3) 1.353(3) |

1.421(3) 1.418(3) |

1.386(2) 1.385(2) |

2.0631(16) 2.0673(16) |

1.9705(16) |

| (MePDI)Ru(C4Ph4)ref.38 | 1.323(3) 1.308(3) |

1.450(3) 1.454(3) |

1.369(3) 1.363(3) |

2.0587(18) 2.0794(18) |

1.9824(18) |

| (MePDI)Ru(Cl)2(CO)ref.37 | 1.302(3) 1.300(3) |

1.475(4) 1.479(4) |

1.346(3) 1.338(3) |

2.130(2) 2.108(2) |

2.0056(19) |

| (MePDI)Ru(Cl)2(PMe3)ref.37 | 1.310(4) 1.314(4) |

1.471(5) 1.460(5) |

1.363(4) 1.346(4) |

2.121(2) 2.116(3) |

1.971(3) |

Butadiene exchange experiments were also conducted with (MePDI)Ru(s-trans-η4-C4H6) for comparison to the iron congener. Addition of butadiene-d6 to a benzene-d6 solution of (MePDI)Ru(s-trans-η4-C4H6) resulted in approximately 10% of the labeled diene after one hour at ambient temperature. Similarly, addition of excess ethylene to a benzene-d6 solution of (MePDI)Ru(s-trans C4H6) with excess ethylene at room temperature produced no evidence for oxidative cyclization to form the ruthenocycloheptene over 24 hours, whereas the [(PDI)Fe] congener undergoes oxidative cyclization immediately.

The piperylene derivative, (MePDI)Ru(s-trans-η4-E-piperylene) proved more reactive as addition of excess ethylene produced a diamagnetic, C1 symmetric product in quantitative yield over the course of 24 hours at ambient temperature. Analysis of the product by multinuclear and two-dimensional NMR spectroscopy established formation of a ruthenacycloheptene complex 1 with α-substitution of the methyl group on the piperylene coupling partner (Scheme 5). The increased reactivity of the piperylene complex and the observed regioselectivity likely arises from dissociation of the substituted olefin in the basal plane of the ruthenium complex, opening a site for substrate coordination and subsequent oxidative cyclization.

Scheme 5.

Stoichiometric reactivity of (MePDI)Ru(s-trans-η4-E-piperylene) relevant to oxidative cyclization.

The formation of a diamagnetic ruthenacycloheptene complex from the addition of ethylene to (MePDI)Ru(s-trans-η4-E-piperylene) contrasts the oxidative cyclization reported for the analogous iron complex. With the latter, only broadening of the signals attributed to (MePDI)Fe(s-trans −η4-E-piperylene) was observed by 1H NMR spectroscopy with no evidence for formation of an 18-electron, diamagnetic metallocycle.18 Instead, a paramagnetic iron metallocycle was implicated where the olefin was dissociated from the metal, giving rise to an Fe(III) dialkyl-type intermediate analogous to the S = 1 complexes observed and crystallographically characterized in alkene-alkene [2+2] cycloaddition.20, 27–28 This phenomenon is likely a result of the decreased coordination affinity of the methyl-substituted propenyl olefin of the metallacycle to iron, leading to increased dissociation of the propenyl group. With ruthenium, the resulting Ru(II) metallocycle is low-spin and diamagnetic due to the stronger coordination of internal olefins to the metal compared to iron. More broadly, the observation of oxidative cyclization with pyridine(diimine) ruthenium complexes where the chelate is redox innocent supports that access to triplet structures in so-called “two-state” reactivity is not a requirement for this C–C bond forming step. These results are consistent with other previously reported oxidative cyclizations with zirconium,24–26, 43 nickel,44–48 and platinum,49 in where the redox events are confined to the metal and the reaction proceeds exclusively on the S = 0 surface. Taken together, these oxidative cyclization studies pinpoint that the differentiating step facilitated by [(PDI)Fe] complexes in the intermolecular [2+2] cyclization event is the facile C(sp3)–C(sp3) reductive elimination.

Elucidating the Origins of C(sp3)–C(sp3) Reductive Elimination.

Previous studies on intermolecular [2+2] cyclization of olefins and diolefins demonstrated that addition of strong-field ligands such as CO or butadiene to pyridine(diimine)iron metallocycles induced reductive elimination and formation of the corresponding cyclobutane product (Scheme 6A).17

Scheme 6.

Mechanistic hypotheses for C(sp3)–C(sp3) reductive elimination to form cyclobutane products.

The observation of apparent ligand-induced reductive elimination raises the question as to the role of substrate and product in the C(sp3)–C(sp3) bond forming step during iron catalyzed [2+2] cycloaddition. One plausible step is the dissociation of the olefin from the 18-electron pyridine(diimine) iron(II) alkyl-allyl metallocycle to open a coordination site. As discussed in the previous section, this dissociation likely results in a spin state change from S = 0 to S = 1 where the triplet intermediate is best described as intermediate spin iron(III) (SFe = 3/2) engaged in antiferromagnetic coupling to a chelate radical anion (Scheme 6B).20, 27–28 The ferric oxidation state is particularly significant, as it has been previously implicated in iron dialkyl complexes to promote C–C bond formation.50

Spin crossover during reductive elimination from an 18-electron, S = 0 metallocycle has been explored computationally by Chen and coworkers,29 although this study did not explicitly address the role of alkene dissociation on a potential change in spin surface that may ultimately lead to cyclobutane formation. Indeed, the S = 0 and S = 1 geometries (TPSS/def2-TZVP) reported by Chen and coworkers for the 18-electron complex are similar (RMSD = 1.612). To explore the possibility of alkene dissociation and a change in spin surface, additional computational studies were conducted using DFT (TPSS/LACVP**). Geometries were optimized on three different spin surfaces: (i) unrestricted Kohn-Sham (UKS) S = 1 triplet (i.e., Fe(II)/[PDI]° metallocycle), (ii) UKS S = 2 quintet (i.e., Fe(III)/[PDI⦁]− metallocycle) with no exchange coupling between Fe and PDI, and (iii) broken-symmetry (BS(3,1)) S = 1 triplet (i.e., antiferromagnetically-coupled Fe(III)/ [PDI⦁]− metallocycle). In the broken-symmetry notation, BS(m,n) describes a state where there are m unpaired spin up electrons and n unpaired spin down electrons on separate fragments – in this case, Fe and PDI. Examination of the bond lengths (Scheme 7) within the metallocycle demonstrate a lengthening of Fe–C bonds, particularly between the vinyl unit and the iron across all Fe(III) compounds. This is consistent with the isomerization event dissociating the vinyl portion of the metallacycloheptene (Table 3).

Scheme 7.

DFT-calculated (TPSS/LACV3P**+//LACVP**) geometries and equilibrium between S = 0 and S = 1 metallocycles. Triplet energies are calculated for three optimized geometries: UKS(S = 1), BS(3,1)//UKS(S = 2), and BS(3,1)//BS(3,1). Bond lengths are reported in Å.

Table 3.

DFT-derived bond lengths of the vinyl fragments of the S = 0 and S = 1 metallacycles. Bond lengths are reported in Å.

| RKS S = 0 | BS(3,1)// BS(3,1) |

UKS S = 1 |

UKS S = 2 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C(1)-C(2) | 1.39 | 1.41 | 1.42 | 1.42 |

| C(2)-C(3) | 1.41 | 1.40 | 1.41 | 1.39 |

| Fe-C(1) | 2.17 | 2.12 | 2.12 | 2.13 |

| Fe-C(2) | 2.11 | 2.13 | 2.11 | 2.18 |

| Fe-C(3) | 2.16 | 2.27 | 2.25 | 2.37 |

Higher-level S = 1 single-points (TPSS/LACV3P**+//LACVP**) on the optimized geometries yield energies 1.4–3.1 kcal mol−1 above the S = 0 geometry, indicating that the triplet metallocycle is accessible at room temperature (1–9% Boltzmann population). This contrasts with Chen and coworkers where a 7.1 kcal/mol energy difference (CASPT2(12,12)/CBS//TPSS/def2-TZVP) between the S = 0 and S = 1 surfaces was reported. Such a large energy difference corresponds a population of the triplet approximately 6 ppm at room temperature. The neglect of alkene dissociation in the reported S = 1 geometry results in a higher-energy geometry (i.e., more vertical than adiabatic in relation to the S = 0 geometry).

The support for ferric iron with a redox-active pyridine(diimine) chelate in cyclobutane formation raises the question as to what role the strong-field ligand (CO, butadiene) plays upon addition to iron metallocycles. One hypothesis is ligand induced reductive elimination, where coordination of the strong field ligand triggers C(sp3)–C(sp3) bond formation likely exclusively on an S = 0 surface. An alternative hypothesis is reductive coupling directly from the S = 1, iron(III) metallacyclopentane to produce coordinated vinylcyclobutane. Reversible activation of the vinylcyclobutane maintains an equilibrium between metallocycle and product-bound species until an equivalent of the incoming ligand displaces the vinylcyclobutane from the coordination sphere of the iron. In this scenario, the incoming strong-field ligand serves to trap the iron from reversible C–C oxidative addition.

13C Labeling Experiments to Explore C(sp3)–C(sp3) Bond Formation.

To determine whether reversible C(sp3)–C(sp3) is occurring in the absence of added ligand, a 13C-labeling experiment was conducted whereby a benzene-d6 solution of (MePDI)Fe(s-trans-η4-C4H6) was treated with 3 equivalents of 13C2H4. Oxidative cyclization quantitatively generated the S = 0, (PDI)Fe metallacycloheptene as judged by 1H and 13C{1H} NMR spectroscopy (Scheme 8A). An excess of ethylene was used to suppress competing retro-[2+2] cyclization of the formed metallocycle that complicated interpretation of the spectroscopic data, and previous studies have shown that excess ethylene does not trigger vinylcyclobutane formation.17 Examination of the metallocyclic product by 13C NMR spectroscopy established incorporation of the isotopic label in three positions – α, β, and γ-carbons – of the metallocycle. This result is inconsistent with a static metallocycle, where oxidative cyclization between butadiene and ethylene would place the 13C label exclusively at the α and β positions. Labeling of the γ-carbon is consistent with a pathway involving rapid C(sp3)–C(sp3) reductive coupling generating coordinated 13C-labeled vinylcyclobutane (Scheme 8B). Rapid rotation about the C–C single bond between the vinyl group and the cyclobutane ring followed by C–C oxidative addition results in migration of the 13C label. This results in the observed statistical mixture of 13C in both the α and γ positions. This finding demonstrates that C(sp3)–C(sp3) reductive coupling and formation of the cyclobutane is fast and reversible.

Scheme 8.

13C2H4 labeling experiments excluding the mechanistic relevance of ligand-induced reductive elimination.

While the 13C labelling experiment supports rapid and reversible C(sp3)–C(sp3) reductive coupling and excludes ligand induced reductive elimination as catalytically relevant, it only provides circumstantial evidence for the requirement of redox cycling to a ferric species with a singly reduced chelate prior to reductive elimination. Further support for the role of ferric iron was obtained from re-examination of the ruthenium metallacycloheptene congener 1 formed from piperylene-ethylene coupling. Synthesis of the 13C-labeled ruthenacycloheptene (1-13C) from addition of 13C2H4 and analysis by NMR spectroscopy established labeling at only the α and β positions demonstrating exclusive oxidative cyclization with no evidence for reversible C(sp3)–C(sp3) reductive coupling (Scheme 9A). Evaluation of (MePDI)Ru(s-trans-η4-E-piperylene) as a precatalyst for the [2+2] cycloaddition of piperylene and ethylene resulted in no product formation even with heating to 50 °C for 24 hours (see Supporting Information for additional details). Monitoring of the attempted catalytic reaction by 1H NMR spectroscopy established formation of the ruthenocycle formed from oxidative cyclization of piperylene and ethylene, further confirming the challenge to turnover is C(sp3)–C(sp3) reductive elimination to form the cyclobutane product.

Scheme 9.

Experiments probing reductive coupling with [(PDI)Ru]. A. Synthesis 1-13C does not result in label scrambling under thermal conditions. B. Irradiation of 1 in the presence of 13C2H4 results in migration of the label in the metallocycle due to reversible C(sp3)–C(sp3) reductive coupling.

Because thermal reductive elimination with pyridine(diimine) ruthenium complexes has a high barrier, photochemical experiments were explored to induce reductive coupling. The pentane solution electronic absorption spectrum of 1 exhibited a feature at 469 nm (ε = 1615 M−1 cm−1), assigned to a metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) band. In the limit full charge separation, this excited state may be described as ruthenium(III) with a pyridine(diimine) radical, raises the promise for photoinduced C(sp3)–C(sp3) bond formation from [(PDI)Ru].

An analogous 13C labeling experiment was conducted whereby 1 was treated with 3 equivalents of 13C2H4 and irradiated with a blue LED lamp (Scheme 9B). Analysis of the product by 13C{1H} NMR after 24 hours of irradiation established the formation of 1-13C along with other products assigned as isomers derived from the asymmetry of piperylene (see Supporting Information for details) in overall 64% conversion. Analysis of 1-13C by 13C NMR spectroscopy revealed incorporation of the isotopic label in the α, β and γ positions, consistent with initial oxidative cyclization followed by reversible, photoinduced C(sp3)–C(sp3) reductive coupling. In contrast to the thermal chemistry observed with [(PDI)Fe], free labeled propenylcyclobutane was not detected in this reaction, presumably due to the increased affinity of vinylcyclobutane to ruthenium as compared to iron. Because the formed cyclobutyl product remains tightly bound to the metal center, displacement by the free diene does not occur before activation of the cyclobutane returns the metallocycle.

The high thermal barrier for C(sp3)–C(sp3) reductive coupling with the pyridine(diimine) ruthenium complex is likely a result of the redox-innocence of the chelate and the inability to thermally populate a Ru(III)/PDI⦁- triplet excited state. By contrast, the singlet-triplet gap of the iron congener is lower (e.g. iron has a higher density of states) providing access the higher oxidation state ferric intermediate that has a lower barrier for cyclobutane formation. These data provide rare experimental support for the design principles governing pincer complexes that will promote catalytic [2+2] cycloaddition: catalysis operates at mild conditions when the complexes cycle to high valent metal centers during catalysis. In this regard, [(PDI)Fe] is privileged due to participation of the redox active PDI ancillary ligand providing a low barrier pathway to the ferric oxidation state.

Factors Relevant to Reversible [2+2] Cyclization and Insight into Chemical Recyclable Cycloaddition Polymers.

A feature of vinylcyclobutane retrocycloaddition that is relevant to chemical recycling of cycloaddition polymers is the ability to undergo C–C bond cleavage upon exposure to a transition metal catalyst. Previous studies have demonstrated both stoichiometric17 and catalytic16 activation of vinylcyclobutane with [(MePDI)Fe(N2)](μ-N2) to generate the diamagnetic S = 0, Fe(II)/(PDI) metallocycle, with subsequent slow loss of ethylene to form (MePDI)Fe(s-trans-η4-C4H6) (Scheme 10A). Similarly, exposure of propenylcyclobutane to [(MePDI)Fe(N2)](μ-N2) resulted in immediate retro-[2+2] cyclization to generate ((MePDI)Fe(s-trans-η4-E-piperylene) with loss of free ethylene as judged by 1H NMR and solution-state Mossbauer spectroscopies (see Supporting Information for details). The instantaneous retro-cyclization is consistent with the lack of observable diamagnetic metallacycle observed in the oxidative cyclization of piperylene and ethylene mediated by [(PDI)Fe].

Scheme 10.

Comparison of thermal retro-[2+2] cycloaddition of vinylcyclobutane with A. [(PDI)Fe] (ref. 27) and B. [(PDI)Ru] systems. ORTEP shown at 30% probability. Hydrogen atoms and disorder in the metallocycle fragment omitted for clarity.

Given the role of PDI reduction on facilitating C(sp3)–C(sp3) reductive elimination, it was also of interest to determine if chelate redox activity was required in cycloreversion. Treatment of a benzene-d6 solution of (MePDI)Ru(s-trans −η4-E-piperylene) with excess vinylcyclobutane produced no reaction at ambient temperature, likely due to the substitutionally inert piperylene ligand. Heating the reaction to 60 °C resulted in piperylene displacement and activation of the vinylcyclobutane to form the ruthenium metallocycloheptane product, 2 (Scheme 10B). The identity of 2 was confirmed by single crystal X-ray diffraction and a molecular geometry similar to the iron congener was observed with an alkyl-η3-allyl-type metallocycle. Ruthenocycle 2 proved remarkably stable in solution for weeks even in the absence of excess ethylene. The corresponding iron complex undergoes facile ethylene extrusion under these conditions.17

The high barrier for 2 to undergo retro-[2+2] cycloaddition is likely due to the thermal inaccessibility of Ru(III), unlike the [(PDI)Fe] congener. Accordingly, heating isolated 1 at 50 °C over the course of 48 hours did not induce the retro-[2+2] process. However, irradiation of the metallocycle with a blue LED lamp facilitated retro-cyclization in 24 hours, affording free ethylene and (MePDI)Ru(s-trans E-piperylene) in 23% conversion (Scheme 11).

Scheme 11.

Photoinduced retro-cyclization of 1.

The ability to induce retro-[2+2] cycloaddition from the photoexcited state of the ruthenium metallocycle contrasts the thermal reactivity of iron and informs on the reactivity profiles for the two metals (Figure 4). For [(PDI)Fe], the higher density of states results in a thermally accessible singlet-triplet gap between the metallocycle isomers after oxidative cyclization and allows for the retro-[2+2] processes to occur readily, albeit slowly, at room temperature (Figure 4A). In contrast, the requirement for irradiation for ruthenium demonstrates that the singlet-triplet gap is much more energetically substantial (Figure 4B). In this case, irradiation results in a charge-separated excited state that is more energetically accessible to the hypothesized triplet state that renders retro-[2+2] cycloreversion energetically feasible. Taken together, the triplet configuration of the metallocycle appears not only relevant to reductive elimination, but to the retro-[2+2] cyclization process as well, as expected from the principle of microscopic reversibility.

Figure 4.

Comparative theoretical reaction profiles for the oxidative cyclization (forward)/retro-[2+2] cyclization (reverse) process for A. (PDI)Fe or B. (PDI)Ru systems.

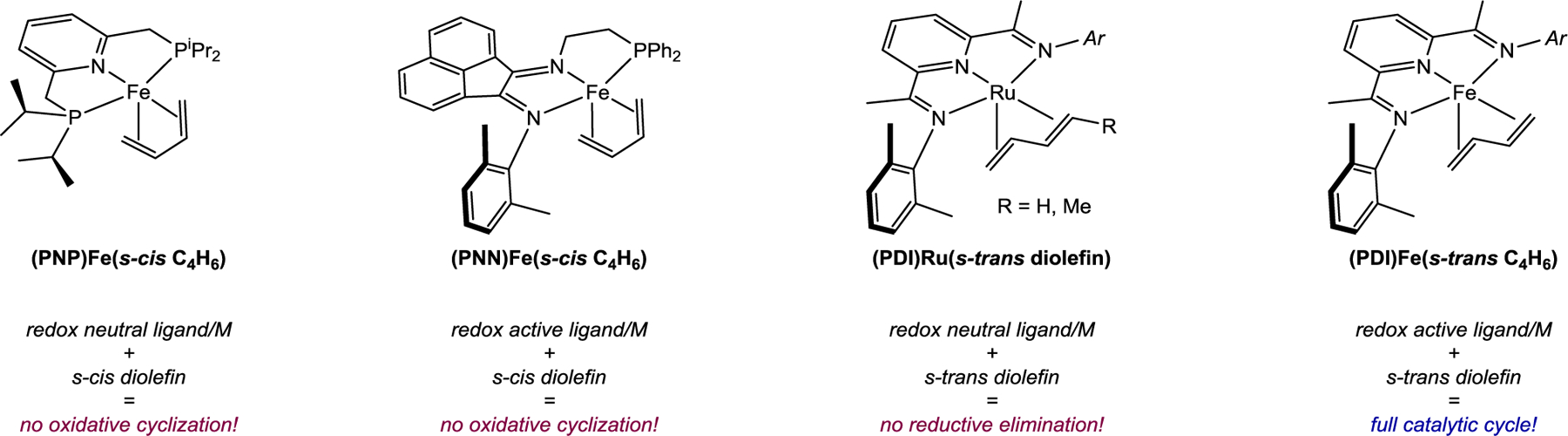

Establishing Catalyst Design Principles for Catalytic [2+2] Cycloaddition of Dienes.

The evaluation of a series of pincer-ligated iron and ruthenium diene complexes in the elementary steps of intermolecular [2+2] cycloaddition establishes two significant design features that facilitate catalytic activity: an s-trans geometry of the conjugated diene to enable oxidative cyclization and the ability to access high valent iron centers for C(sp3)–C(sp3) reductive elimination (Figure 5). For the former feature, the representative complexes (PNP)Fe(s-cis-η4-C4H6) and (PNN)Fe(s-cis-η4-C4H6) did not undergo intermolecular oxidative cyclization in the presence of excess ethylene and thus were not catalytically competent for the cyclization reaction. From a design standpoint, the ability to support s-trans ligation at 5 coordinate pincer iron complexes is correlated to pincer ligand rigidity, as determined by the complex’s plane angle. Our computational results indicate that, above plane angles above 155°, there is a preference for s-trans diolefin ligation at (CO)3Fe(η4-C4H6) model complexes. Synthesis and crystallographic characterization of (PNP)Fe(s-cis-η4- C4H6) and (PNN)Fe(s-cis-η4-C4H6) along with previously reported crystallographic data of (PDI)Fe(s-trans C4H6) complexes18, 22, 23 indicate that this trend maps on to 5 coordinate iron pincer complexes as well.

Figure 5.

Summary of structure-activity relationships elucidated relevant to the thermal intermolecular [2+2] cycloaddition of dienes and olefins using pincer ligated metal systems.

The data from these studies also establishes that oxidative cyclization occurs from metal diene complexes with an s-trans geometry without the requirement for redox events at the chelate. However, the reductive coupling event leading to cyclobutane formation has an inaccessibly high barrier in the absence of an accessible higher oxidation state, which in the case of pyridine(diimine) iron complexes is facilitated by the redox-active ligand. These experimental results corroborate previous computational work by Chen and coworkers, in which spin crossover prior to reductive elimination was determined to be crucial to productive intermolecular [2+2] cycloaddition activity at [(PDI)Fe].29

Based on this body of mechanistic information, a full catalytic cycle for the intermolecular [2+2] cyclization of butadiene and ethylene at (PDI)Fe centers is presented in Scheme 12. The s-trans coordination of butadiene precludes olefin arm dissociation, which then opens a coordination site for ethylene ligation. Oxidative cyclization then produces an equilibrium distribution of metallocyclic intermediates, with the equilibrium favoring the spectroscopically observable Fe(II)/PDI, S = 0, 18-electron metallacycloheptene. Population of the S = 1, formally Fe(III)/[PDI]·- metallocycle exists under catalytic conditions and mediates C(sp3)–C(sp3) reductive coupling. However, because of the pendent vinyl group on vinylcyclobutane, there is also an equilibrium between product-bound (PDI)Fe species and S = 1 metallocycle that inhibits product loss and overall catalytic turnover. The displacement of vinylcyclobutane bound to the Fe center with additional butadiene substrate then completes the cycle. The elucidation of this mechanism provides a platform by which to design more active catalysts for the intermolecular [2+2] cycloaddition of feedstock dienes and olefins.

Scheme 12.

Proposed catalytic cycle for the intermolecular [2+2] cycloaddition of butadiene and ethylene catalyzed by [(PDI)Fe] complexes.

CONCLUSION

In summary, the features (PDI)Fe(diene) complexes responsible for the unique catalytic [2+2] cyclization activity and its microscopic reverse, retro-[2+2] cycloaddition relevant to depolymerization, have been elucidated. A combination of rare trans-diene coordination enables the first C–C bond forming event and does not rely on redox participation of the supporting ligand. The second C–C bond-forming event, C(sp3)–C(sp3) reductive coupling, forms the four-membered ring and relies on access to a triplet state that generates the ferrous oxidation state. For iron catalysts, the density of states of the first-row metal renders this step thermally accessible and enables unique bond formation and deconstruction.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Financial support from ExxonMobil is gratefully acknowledged. M.M.B. thanks the NIH for a Ruth Kirschstein National Research Service Award (F32 GM134610). We also thank Boran Lee (Princeton University) for preparation of (PNP)FeBr2.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this publication is included free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Experimental data, including synthesis and characterization of compounds, catalytic data, labeling and photoexcitation experiments as well as other stoichiometric reactions (PDF).

Crystallographic information for (PNP)Fe(s-cis C4H6), (PNN)Fe(s-cis C4H6), (MePDI)Ru(s-trans E-piperylene) and 2 (CIF).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bauer MR; Di Fruscia P; Lucas SCC; Michaelides IN; Nelson JE; Storer RI; Whitehurst BC, Put a ring on it: application of small aliphatic rings in medicinal chemistry. RSC Med. Chem 2021. 12 (4), 448–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marson CM, New and unusual scaffolds in medicinal chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev 2011, 40 (11), 5514–5533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Namyslo JC; Kaufmann DE, The Application of Cyclobutane Derivatives in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev 2003, 103 (4), 1485–1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lovering F; Bikker J; Humblet C, Escape from Flatland: Increasing Saturation as an Approach to Improving Clinical Success. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52 (21), 6752–6756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor RD; MacCoss M; Lawson ADG, Rings in Drugs. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57 (14), 5845–5859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aldeghi M; Malhotra S; Selwood DL; Chan AWE, Two- and Three-dimensional Rings in Drugs. Chem. Biol. Drug Des 2014, 83 (4), 450–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seiser T; Saget T; Tran DN; Cramer N, Cyclobutanes in Catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2011, 50 (34), 7740–7752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoppens NC; Hudnall TW; Foster A; Booth CJ, Aliphatic–aromatic copolyesters derived from 2,2,4,4-tetramethyl-1,3-cyclobutanediol. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry 2004, 42 (14), 3473–3478. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelsey DR; Scardino BM; Grebowicz JS; Chuah HH, High Impact, Amorphous Terephthalate Copolyesters of Rigid 2,2,4,4-Tetramethyl-1,3-cyclobutanediol with Flexible Diols. Macromolecules 2000, 33 (16), 5810–5818. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Z; Miller B; Mabin M; Shahni R; Wang ZD; Ugrinov A; Chu QR, Cyclobutane-1,3-Diacid (CBDA): A Semi-Rigid Building Block Prepared by [2+2] Photocyclization for Polymeric Materials. Scientific Reports 2017, 7 (1), 13704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Natta G; Dall’Asta G; Mazzanti G; Motroni G, Stereospecific polymerization of cyclobutene. Die Makromolekulare Chemie 1963, 69 (1), 163–179. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall HK Jr.; Ykman P, Addition polymerization of cyclobutene and bicyclobutane monomers. Journal of Polymer Science: Macromolecular Reviews 1976, 11 (1), 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall HK Jr.; Padias AB, Bicyclobutanes and cyclobutenes: Unusual carbocyclic monomers. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry 2003, 41 (5), 625–635. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moss FR; Shuken SR; Mercer JAM; Cohen CM; Weiss TM; Boxer SG; Burns NZ, Ladderane phospholipids form a densely packed membrane with normal hydrazine and anomalously low proton/hydroxide permeability. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115 (37), 9098–9103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sinninghe Damsté JS; Strous M; Rijpstra WIC; Hopmans EC; Geenevasen JAJ; van Duin ACT; van Niftrik LA; Jetten MSM, Linearly concatenated cyclobutane lipids form a dense bacterial membrane. Nature 2002, 419 (6908), 708–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohadjer Beromi M; Kennedy CR; Younker JM; Carpenter AE; Mattler SJ; Throckmorton JA; Chirik PJ, Iron-catalysed synthesis and chemical recycling of telechelic 1,3-enchained oligocyclobutanes. Nat. Chem 2021, 13 (2), 156–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russell SK; Lobkovsky E; Chirik PJ, Iron-Catalyzed Intermolecular [2π + 2π] Cycloaddition. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133 (23), 8858–8861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennedy CR; Zhong H; Joannou MV; Chirik PJ, Pyridine(diimine) Iron Diene Complexes Relevant to Catalytic [2+2]-Cycloaddition Reactions. Adv. Synth. Catal 2020, 362 (2), 404–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cannell LG, Cyclodimerization of ethylene and 1,3-butadiene to vinylcyclobutane. Homogeneous titanium catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1972, 94 (19), 6867–6869. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joannou MV; Hoyt JM; Chirik PJ, Investigations into the Mechanism of Inter- and Intramolecular Iron-Catalyzed [2 + 2] Cycloaddition of Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142 (11), 5314–5330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kennedy CR; Joannou MV; Steves JE; Hoyt JM; Kovel CB; Chirik PJ, Iron-Catalyzed Vinylsilane Dimerization and Cross-Cycloadditions with 1,3-Dienes: Probing the Origins of Chemo- and Regioselectivity. ACS Catal 2021, 11 (3), 1368–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bouwkamp MW; Bowman AC; Lobkovsky E; Chirik PJ, Iron-Catalyzed [2π + 2π] Cycloaddition of α,ω-Dienes: The Importance of Redox-Active Supporting Ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128 (41), 13340–13341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Russell SK; Milsmann C; Lobkovsky E; Weyhermüller T; Chirik PJ, Synthesis, Electronic Structure, and Catalytic Activity of Reduced Bis(aldimino)pyridine Iron Compounds: Experimental Evidence for Ligand Participation. Inorg. Chem 2011, 50 (7), 3159–3169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erker G; Wicher J; Engel K; Krüger C, (s-trans-η4-Dien)zirconocen-Komplexe. Chem. Ber 1982, 115 (10), 3300–3310. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erker G; Engel K; Dorf U; Atwood JL; Hunter WE, The Reaction of (Butadiene)zirconocene and -hafnocene with Ethylene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 1982, 21 (12), 914–914. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erker G; Engel K; Dorf U; Atwood JL; Hunter WE, Die Reaktion von (Butadien)zirconocen und -hafnocen mit Ethylen. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 1982, 21 (S12), 1974–1983. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoyt JM; Sylvester KT; Semproni SP; Chirik PJ, Synthesis and Electronic Structure of Bis(imino)pyridine Iron Metallacyclic Intermediates in Iron-Catalyzed Cyclization Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135 (12), 4862–4877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Darmon JM; Stieber SCE; Sylvester KT; Fernández I; Lobkovsky E; Semproni SP; Bill E; Wieghardt K; DeBeer S; Chirik PJ, Oxidative Addition of Carbon–Carbon Bonds with a Redox-Active Bis(imino)pyridine Iron Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134 (41), 17125–17137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu L; Chen H, Substrate-Dependent Two-State Reactivity in Iron-Catalyzed Alkene [2+2] Cycloaddition Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139 (44), 15564–15567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Groom CR; Bruno IJ; Lightfoot MP; Ward SC, The Cambridge Structural Database. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Sci., Cryst. Eng. Mater 2016, 72 (2), 171–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bart SC; Lobkovsky E; Chirik PJ, Preparation and Molecular and Electronic Structures of Iron(0) Dinitrogen and Silane Complexes and Their Application to Catalytic Hydrogenation and Hydrosilation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126 (42), 13794–13807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mills OS; Robinson G, Studies of some carbon compounds of the transition metals. IV. The structure of butadiene irontricarbonyl. Acta Cryst 1963, 16 (8), 758–761. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schaefer BA; Margulieux GW; Tiedemann MA; Small BL; Chirik PJ, Synthesis and Electronic Structure of Iron Borate Betaine Complexes as a Route to Single-Component Iron Ethylene Oligomerization and Polymerization Catalysts. Organometallics 2015, 34 (23), 5615–5623. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmiege BM; Carney MJ; Small BL; Gerlach DL; Halfen JA, Alternatives to pyridinediimine ligands: syntheses and structures of metal complexes supported by donor-modified α-diimine ligands. Dalton Trans 2007, (24), 2547–2562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trovitch RJ; Lobkovsky E; Chirik PJ, Bis(diisopropylphosphino)pyridine Iron Dicarbonyl, Dihydride, and Silyl Hydride Complexes. Inorg. Chem 2006, 45 (18), 7252–7260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Russell SK; Darmon JM; Lobkovsky E; Chirik PJ, Synthesis of Aryl-Substituted Bis(imino)pyridine Iron Dinitrogen Complexes. Inorg. Chem 2010, 49 (6), 2782–2792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gallagher M; Wieder NL; Dioumaev VK; Carroll PJ; Berry DH, Low-Valent Ruthenium Complexes of the Non-innocent 2,6-Bis(imino)pyridine Ligand. Organometallics 2010, 29 (3), 591–603. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wieder NL; Carroll PJ; Berry DH, Structure and Reactivity of Acetylene Complexes of Bis(imino)pyridine Ruthenium(0). Organometallics 2011, 30 (8), 2125–2136. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wieder NL; Gallagher M; Carroll PJ; Berry DH, Evidence for Ligand Non-innocence in a Formally Ruthenium(I) Hydride Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132 (12), 4107–4109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bart SC; Chłopek K; Bill E; Bouwkamp MW; Lobkovsky E; Neese F; Wieghardt K; Chirik PJ, Electronic Structure of Bis(imino)pyridine Iron Dichloride, Monochloride, and Neutral Ligand Complexes: A Combined Structural, Spectroscopic, and Computational Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128 (42), 13901–13912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Bruin B; Bill E; Bothe E; Weyhermüller T; Wieghardt K, Molecular and Electronic Structures of Bis(pyridine-2,6-diimine)metal Complexes [ML2](PF6)n (n = 0, 1, 2, 3; M = Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn). Inorg. Chem 2000, 39 (13), 2936–2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Römelt C; Weyhermüller T; Wieghardt K, Structural characteristics of redox-active pyridine-1,6-diimine complexes: Electronic structures and ligand oxidation levels. Coord. Chem. Rev 2019, 380, 287–317. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Erker G; Dorf U; Benn R; Reinhardt RD; Petersen JL, Reaction of diene Group 4 metallocene complexes with metal carbonyls: a novel entry to Fischer-type carbene complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1984, 106 (24), 7649–7650. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benn R; Büssemeier B; Holle S; Jolly PW; Mynott R; Tkatchenko I; Wilke G, Transition metal allyls: VI. The stoichiometric reaction of 1,3-dienes with ligand modified zerovalent-nickel systems. J. Organomet. Chem 1985, 279 (1), 63–86. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilke G; Bogdanovič B; Borner P; Breil H; Hardt P; Heimbach P; Herrmann G; Kaminsky H-J; Keim W; Kröner M; Müller H; Müller EW; Oberkirch W; Schneider J; Stedefeder J; Tanaka K; Weyer K; Wilke G, Cyclooligomerization of Butadiene and Transition Metal π-Complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 1963, 2 (3), 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilke G, Contributions to Organo-Nickel Chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 1988, 27 (1), 185–206. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tobisch S; Ziegler T, [Ni0L]-Catalyzed Cyclodimerization of 1,3-Butadiene: A Comprehensive Density Functional Investigation Based on the Generic [(C4H6)2Ni0PH3] Catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124 (17), 4881–4893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ogoshi S; Tonomori K.-i.; Oka M.-a.; Kurosawa H, Reversible Carbon−Carbon Bond Formation between 1,3-Dienes and Aldehyde or Ketone on Nickel(0). J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128 (21), 7077–7086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barker GK; Green M; Howard JAK; Spencer JL; Stone FGA, Organoplatinum complexes related to the cyclodimerization of 1,3-dienes. Reactions of 2,3-dimethylbuta-1,3-diene and buta-1,3-diene with bis(cycloocta-1,5-diene)platinum or bis(ethylene)trimethylphosphineplatinum. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1976, 98 (11), 3373–3374. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lau W; Huffman JC; Kochi JK, Electrochemical oxidation-reduction of organometallic complexes. Effect of the oxidation state on the pathways for reductive elimination of dialkyliron complexes. Organometallics 1982, 1 (1), 155–169. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.