Abstract

Whole-genome sequence analysis of noroviruses is routinely performed by employing a metagenomic approach. While this methodology has several advantages, such as allowing for the examination of co-infection, it has some limitations, such as the requirement of high viral load to achieve full-length or near full-length genomic sequences. In this study, we used a pre-amplification step to obtain full-length genomic amplicons from 39 Canadian GII isolates, followed by deep sequencing on Illumina and Oxford Nanopore platforms. This approach significantly reduced the required viral titre to obtain full-genome coverage. Herein, we compared the coverage and sequences obtained by both platforms and provided an in-depth genomic analysis of the obtained sequences, including the presence of single-nucleotide variants and recombination events.

Keywords: norovirus, full-length amplicons, Illumina MiSeq, Oxford Nanopore, single-nucleotide variation, recombination

1. Introduction

Noroviruses are the most common agents causing acute gastroenteritis, leading to an estimated 684 million illnesses and approximately $60 billion in societal costs worldwide (Bartsch et al., 2016). There are currently no vaccines or therapeutics licensed against norovirus (Cates et al., 2020). Norovirus transmission primarily occurs by person-to-person contact through the faecal–oral route or contaminated food and surfaces (Teunis et al., 2015).

Noroviruses belong to the Caliciviridae family and have a 7.5-kb, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genome that is enclosed in a non-enveloped icosahedral capsid (Green 2013). The genome is organized into three open reading frames (ORFs). ORF1 encodes a polyprotein that is cleaved into six non-structural viral proteins, including the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). ORF2 encodes VP1, the major structural capsid protein, and ORF3 encodes VP2, a minor structural capsid protein (Green 2013). Noroviruses are considered fast-evolving viruses (de Graaf, van Beek, and Koopmans 2016), and their genomes are tremendously diverse due to the accumulation of point mutations and recombination (Parra 2019). To date, noroviruses are classified into at least ten genogroups. Noroviruses are further classified into at least 49 genotypes based on the diversity of ORF2 and 60 types based on the diversity of the RdRP gene (Chhabra et al., 2019).

Whole-genome sequence (WGS) analysis of noroviruses, which is often carried out through metagenomic approaches, has allowed for source attribution, lineage analysis, identification of recombination events, and variant analysis (Parra and Green 2015; Nasheri et al., 2017; Petronella et al., 2018). However, a high viral titre is required to obtain a full-genome coverage through metagenomics approaches (Nasheri et al., 2017). Alternatively, amplicon-based sequencing using sequence-specific primer sets decreases the viral load requirement in the sample but introduces amplification bias and assumes conserved viral synteny, which could lead to overlooking genomic variations (Cotten et al., 2014). Parra and colleagues have recently developed a method to amplify full-length norovirus GII genomes, followed by the use of the Illumina platform to obtain deep sequencing data on the full-genome amplicons (Parra et al., 2017).

Third-generation sequencing devices such as Oxford Nanopore’s MinION, which can produce long reads up to 100s of kilobases, have become the method of choice to elucidate viral recombination and to identify subgenomic sequences (Viehweger et al., 2019). On the other hand, second-generation sequencing technologies like Illumina, despite a low error rate, are restricted by a read length of ≤300 nt, which, even using paired-end strategies, can limit contiguous assembly when there are repeat or multicopy sequences exceeding the read length. This results in shorter contigs and can considerably complicate the investigation of recombination and the identification of subgenomic sequences. However, the adoption of MinION sequencing for routine surveillance of viruses has been limited due to concerns of sequence accuracy (Bull et al., 2020). To overcome this concern, we performed amplicon-based long-read MinION and short-read paired-end Illumina MiSeq sequencing on matched norovirus-positive stool samples.

The aim of this study is to combine Illumina and Oxford Nanopore sequencing data to reconstruct a highly accurate consensus sequence of the norovirus isolates and to provide insight into the viral recombination and genetic diversity.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Samples

The norovirus GII-positive samples are from the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control (BMH19-089 to BMH19-137), obtained in winter and spring 2019, and from the archive of the National Food Virology Reference Centre at Health Canada (BMH11-021, BMH12-030, BMH 13-039, BMH14-054, BMH14-056, BMH15-059, BMH15-063, BMH16-074, BMH16-077, BMH18-086, and BMH18-087), which were obtained from winter 2011 to spring 2018. The presence of norovirus GII RNA was confirmed by droplet digital PCR (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, USA) using the probes and primers that were described previously (Nasheri et al., 2017; Petronella et al., 2018). The samples either were from an outbreak or were sporadic. An outbreak includes more than two epidemiologically linked cases with more than one norovirus-positive sample. This study has been granted an exemption from requiring ethics approval by Health Canada, and formal consent was not required because the study participants were anonymized.

2.2. RNA extraction and full-length amplicon generation

Full-length amplicons were generated as described before (Parra et al., 2017). Briefly, 10 per cent stool suspensions were clarified by centrifugation (6000 × g for 5 min), and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.45-μM, and then a 0.22-μM filter (Millipore, Etobicoke, Ontario, Canada). RNA was extracted from the filtrate using the MagMax Viral RNA Isolation Kit (Ambion) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from the viral RNA using the Tx30SXN primer (GACTAGTTCTAGATCGCGAGCGGCCGCCCTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT (Katayama et al., 2002) and the Maxima H Minus First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Amplification of the full-length genome was performed using a set of primers that target the conserved regions of the 5ʹ- and 3ʹ-end of GII noroviruses (GII1-35: GTGAATGAAGATGGCGTCTAACGACGCTTCCGCTG and Tx30SXN) and the SequalPrep Long PCR Kit (Invitrogen) following manufacturer’s recommendations.

2.3. Viral RNA load determination

Viral titres were determined by droplet digital PCR (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, USA) using the probes and primers that were described previously (Nasheri et al., 2017; Petronella et al., 2018).

2.4. Sanger sequencing

Samples that did not generate full-length replicons after three attempts were subjected to dual typing by Sanger sequencing. For this purpose, we performed conventional (reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction) RT-PCR targeting of a 570-bp product that includes the 3ʹ-end of the polymerase region and the 5ʹ-end of the major capsid gene followed by Sanger sequencing, as described previously (Cannon et al., 2019).

2.5. Illumina sequencing

Norovirus libraries were constructed using the NexteraXT DNA Library Preparation Kit and Nextera XT Index Kit v2 according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina Inc.). Paired-end Illumina sequencing was performed on a MiSeq instrument (v3 chemistry, 2 × 300 bp) according to manufacturer instructions (Illumina Inc.).

2.6. Oxford Nanopore sequencing

Norovirus cDNA samples were treated with 0.16 mg/ml RNase A (100 mg/ml, Qiagen) for 30 minutes at 37°C. Samples were subsequently size selected using modified Solid Phase Reversible Immobilization (SPRI) magnetic beads to remove DNA fragments <1,500 bp (Hosomichi et al., 2014). Briefly, 1 ml of Ampure XP beads (Beckman Coulter) was applied to a magnetic stand and the supernatant was discarded. The beads were resuspended in 0.5 ml of 20 per cent Polyethylene glycol (PEG) and 2.5 M NaCl solution. The modified SPRI beads were added to DNA samples at a 0.35× volume and incubated for 5 minutes at room temperature. Samples were applied to a magnetic stand, the supernatant discarded, and beads washed 2× with 125 µl 80 per cent ethanol. The beads were air dried for 30 seconds, followed by incubation for 2 minutes at room temperature in 45 µl H2O. Samples were applied to a magnetic stand, and the eluted DNA was quantified using a Qubit 4 Fluorometer (Fisher).

DNA libraries were constructed using the Ligation Sequencing Kit 1D (SQK-LSK108) and the PCR Barcoding Expansion 1–12 Kit (EXP-PBC001) according to the manufacturer protocol (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford Science Park, UK). Twelve barcoded libraries were pooled per run and sequenced on a 1D MinION device (R9.4, FLO-MIN106) using FLO-MIN106 flow cells for up to 24 hours. Signal processing, base calling, demultiplexing and adapter trimming were performed using the Guppy (Guppy GPU v 3.3.3 + fa743ab).

2.7. Bioinformatic analysis

2.7.1. Read processing, de novo whole-genome assembly, and genome annotation

Illumina data set quality was assessed by FastQC (v0.11.8), followed by read processing using Fastp (v 0.20.0) (Chen et al., 2018) to remove adapter and barcode sequences, correct mismatched bases in overlaps, and filter low-quality reads. Nanopore data set quality was analysed using NanoPlot (v1.20.0) (De Coster et al., 2018), and full-genome length Nanopore reads 7.5–7.7 kb were extracted using NanoFilt (v2.7.1) (De Coster et al., 2018). Nanopore reads were taxonomically classified using Kaiju (v1.7.3) (Menzel, Ng, and Krogh 2016) and the viral Kaiju database (NCBI RefSeq database curated 25 May 2020). The top-scoring read was extracted using Seqtk (v1.3, https://github.com/lh3/seqtk), and non-norovirus GII-specific reads were discarded.

Error correction of the full-genome length Nanopore read for each sample was performed using the consensus function of Medaka (v1.1.3, https://github.com/nanoporetech/medaka) and Medaka model r941_min_fast_g303 to polish the sequence using Nanopore long reads. The sequence was further polished using Pilon (v1.23) (Walker et al., 2014) and Illumina short reads using default parameters to obtain the consensus sequence. The WGSs were genotyped using the Norovirus Genotyping Tool v2.0 (Kroneman et al., 2011) and annotated using Vapid (v1.6.6) (Shean et al., 2019) and the Vapid viral database (NCBI complete viral genomes curated 1 May 2018).

2.7.2. Coverage plots

Illumina and Nanopore reads were mapped to the norovirus de novo whole genomes using BBMap (v38.18, https://sourceforge.net/projects/bbmap). Depth of coverage was assessed using the Samtools depth function (v1.7, https://github.com/samtools/samtools), and data were graphed using GraphPad (v6.01).

2.7.3. Phylogenetic analysis

Nucleotide sequences for ORF1, ORF2, and ORF3 from each norovirus strain and closely related GenBank reference sequences (MK753033, KJ407074, MT409884, MH218671, KC576912, MK762635, KX158279, MT731279, MN996298, and KU757046) were aligned with MUSCLE using MEGA (v10.1.8) (Tamura et al., 2013). Maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees based on the Tamura–Nei model were constructed and visualized in MEGA using the aligned sequences and 1,000 bootstrap replicates.

2.7.4. Single-nucleotide variant analysis

Single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) were identified for each norovirus sample with Breseq (v0.35.5) (Deatherage and Barrick 2014) using the mutation prediction pipeline and default parameters. Variants were identified using the norovirus Illumina reads for each sample and highly similar complete genome GenBank references. GenBank accessions used were MK753033, KJ407074, MT409884, MH218671, KC576912, MK762635, KX158279, MT731279, MN996298, and KU757046.

Variant analysis of unfiltered Nanopore data mapped to the corresponding norovirus consensus genome was performed using MiniMap2 v2.20 (r1061) and Nano-Q (commit f1ebf0cb5a972417340b6e2bb4b93089d3b9ca78) as per Riaz et al. (Riaz et al., 2021) using a max length of 7700 nt; quality = 5; jump = 10; min cluster >1.

2.7.5. Recombination analysis

Whole-genome assemblies for the 39 isolates and closely related GenBank reference sequences (MK753033, KJ407074, MT409884, MH218671, KC576912, MK762635, KX158279, MT731279, MN996298, and KU757046) were aligned with MUSCLE using MEGA (v10.1.8) (Tamura et al., 2013). Recombination breakpoints and identification of potential parental sequences were performed using the Recombination Detection Program (RDP4) (v4.101) (Martin et al., 2015) using seven recombination methodologies: RDP, GENECONV, MaxChi, Bootscan, Chimera, SiScan, and 3Seq. A sliding window of 200-bp and a step size of 20 bp, and a multiple-comparison corrected P < 0.05 were used.

2.7.6. Data availability

The complete de novo genome sequences of the 39 norovirus isolates used in this study have been uploaded to the GenBank under accession numbers: Y18883 to MW661284. All SRAs are available in the GenBank under BioProject ID PRJNA713985.

3. Results

3.1. Amplicon production

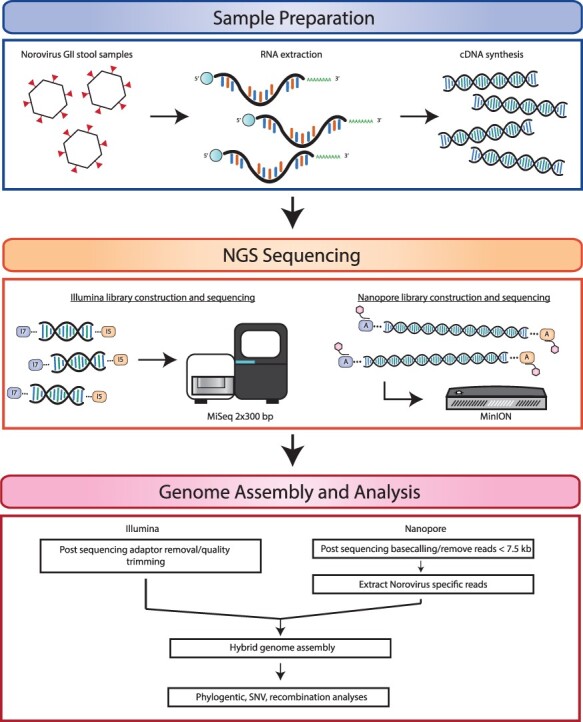

To examine whether full-length amplicons could be generated for a variety of GII samples, we employed the primers that encompass 5ʹUTR to 3ʹUT on 57 GII-positive samples (44 were isolated in 2019, and the remaining 13 were archived samples isolated since 2011). Full-length amplicons were obtained from 39 samples, and multiple efforts for the remaining 18 samples failed to generate any full-length amplicons. Thus, we conducted conventional RT-PCR to obtain partial amplicons for dual typing of these samples by Sanger sequencing. Four out of 18 samples failed to generate any RT-PCR product for dual typing. The full-length amplicons obtained from all 39 samples were subjected to both Illumina and Nanopore sequencing as depicted in Fig. 1. The data obtained from both approaches were used to assemble the full genomes and for further sequence analysis.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of experimental approach for norovirus de novo whole-genome sequencing, assembly, and bioinformatics analysis. Norovirus viral RNA was extracted from stool samples, followed by full-length cDNA amplification. cDNA was sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq platform and an Oxford Nanopore MinION device to obtain high-quality short-read and long-read data, respectively. Illumina and Nanopore reads were processed to remove adaptor and barcode sequences, followed by the quality trimming of Illumina reads and length filtering of Nanopore reads. A combined approach using both Illumina and Nanopore reads was used to produce de novo full-length norovirus genomes. Genome annotation and downstream analyses were performed using the norovirus assemblies.

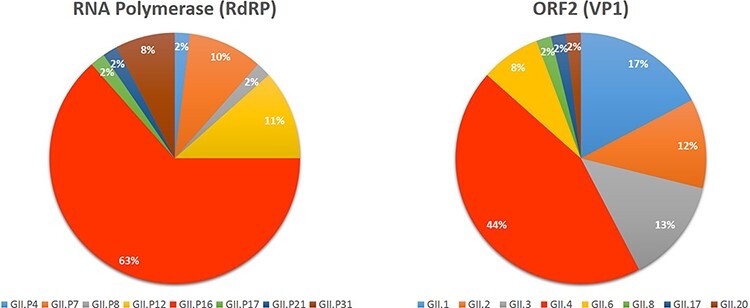

As shown in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S1, GII.P16 (63 per cent) was the dominant polymerase type, followed by GII.P12 (11 per cent), GII.P7 (10 per cent), and GII.P31 (8 per cent). As expected, GII.4 (44 per cent) was the most prevalent genotype, followed by GII.1 (17 per cent), GII.3 (13 per cent), GII.2 (12 per cent), and GII.6 (8 per cent). The dominant GII.P16 was mostly associated with GII.4, making GII.4[P16] the most prevalent strain (30 per cent); however, it was also associated with GII.1 and GII.2 (Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 2.

Norovirus genotypes identified in this study. Norovirus Genotyping Tool v2.0 was used to determine the polymerase type (A) and the capsid/ORF2 genotype (B) of all the samples sequenced (by Sanger or next-generation sequencing) in this study.

3.2. Analysis of the assay sensitivity

To determine the lowest viral genome copy number that would produce full-length amplicons, we made serial dilutions for four representative samples: BMH16-77, BMH18-86, BMH19-95, and BMH19-96. The full-length amplicons generated from the highest dilution (lowest viral load) were subjected to Illumina sequencing to ensure that the full-genome sequence could still be obtained. As shown in Table 1, the lowest viral RNA titre that generated full-length sequence ranged from 1.7 to 3.4 × 102 RNA copy number.

Table 1.

The lowest RNA copy number that generated full-length amplicons.

| Sample ID | RNA titre | Lowest titre–generated amplicon |

|---|---|---|

| BMH16-77 | 4.90E + 06 | 2.70E + 02 |

| BMH18-86 | 2.20E + 06 | 2.10E + 02 |

| BMH19-95 | 3.40E + 06 | 1.70E + 02 |

| BMH19-96 | 3.50E + 07 | 3.40E + 02 |

3.3. Comparison between Illumina and MinION coverage

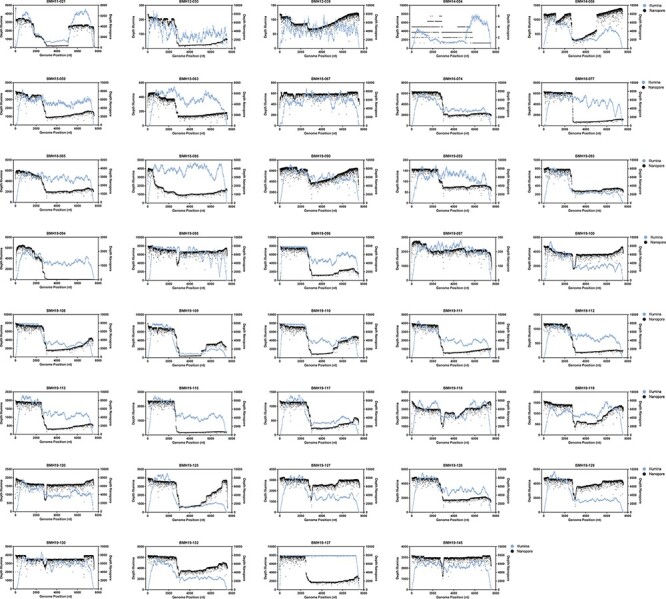

To compare sequencing coverage along the full length of the norovirus genomes, coverage depth analysis was demonstrated for all samples (Fig. 3). For each sample, the Illumina and Nanopore reads were mapped to their corresponding consensus sequence and the sequencing depth at each nucleotide position was determined. As shown in Fig. 3, the Illumina and Nanopore read data produced similar patterns of coverage depth across the length of the norovirus genomes. For the representative samples BMH19-096 (GII.1[P16]), BMH12-030 (GII.4[P4]), BMH19-094 (GII.4[P16]), and BMH15-059 (GII.4[P31]), the Nanopore data showed increased sequencing depth across ∼2,500 bp of ORF1 of the genome. A similar trend is also observed in the Illumina sequencing data, although not as pronounced. The Illumina and Nanopore data for BMH11-021 (GII.2[P16]) showed increased depth of coverage across the first ∼2,500 bp of ORF1 and the last ∼2,500 bp corresponding to ORF2 and ORF3. Interestingly, the Nanopore data for BMH18-086 (GII.8[P8]) had a large increase in depth across ∼500 bp at the 5ʹ end of the genome in contrast to the Illumina data, which showed consistent sequencing depth across the entire length of the genome (excluding the 5ʹ and 3ʹ ends of the genome). Consistent sequencing depth coverage across the genome was observed for BMH19-120 (GII.3[P12]), BMH 19-095 (GII.3[P21]), BMH19-118 (GII.6[P7]), and BMH15-067 (GII.17[P17]) for both sequencing technologies.

Figure 3.

Coverage profiles of norovirus samples using Illumina and Nanopore read data. Reads were mapped to the de novo consensus sequence for each genotype and read type. Depth across the genome at each nucleotide position for Illumina (blue) and Nanopore (black) is shown.

Overall, the Illumina data typically lacked coverage at both the 5ʹ and 3ʹ ends of the norovirus genomes (Fig. 3), resulting in incomplete genome assemblies and only partial coding sequence data for ORF1 (data not shown). In contrast, the Nanopore reads yielded full-length sequences, which covered both the 5ʹ and 3ʹ ends of the norovirus genome. Additionally, using the Nanopore reads made it possible to obtain complete and/or partially complete sequences of the 5ʹ and 3ʹ UTR regions, with the exception of the first 35 nt at the 5ʹ end, which are from the primer used for amplification.

3.4. Phylogenetic analysis

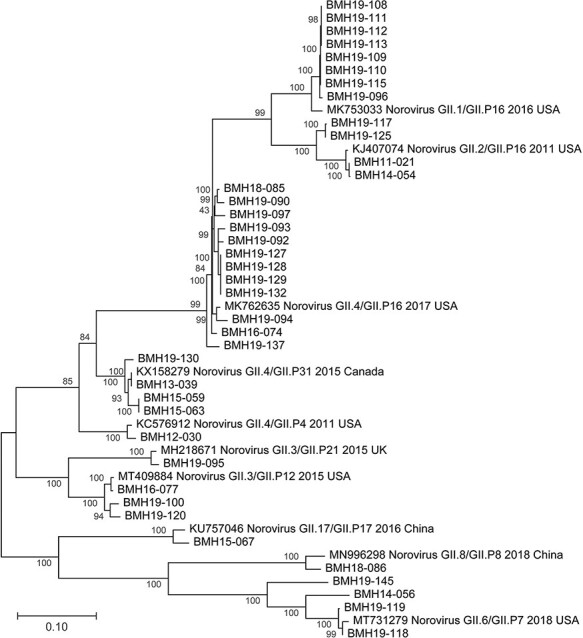

Phylogenetic analysis of the 39 Canadian de novo assembled norovirus strains from this study was performed for ORF1, ORF2, and ORF3 (Supplementary Fig. S1A–C), as well as the full genomes (Fig. 4). The epidemiologically linked samples such as BMH-19-108 to BMH-19-115 and BMH-19-127 to BMH-19-132 cluster closely together across all three ORFs, providing genetic evidence to the epidemiological data. As expected for norovirus infections, inter-host variations were not observed between the linked samples.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic trees of Canadian norovirus GII full-genome sequences obtained from this study. Maximum likelihood trees were constructed using MEGA (v10.1.8) and 1,000 bootstrap replicates. The scale bars represent the phylogenetic distance expressed as nucleotide substitutions per site. Reference sequences were obtained from GenBank with accession numbers, genotype, year and country of isolation shown.

ORF1/ORF2 recombinants GII.4/GII.P16 (n = 13), GII.2/GII.P16 (n = 4), and GII.3/GII.P12 (n = 2) were also frequently observed (Supplementary Table S2).

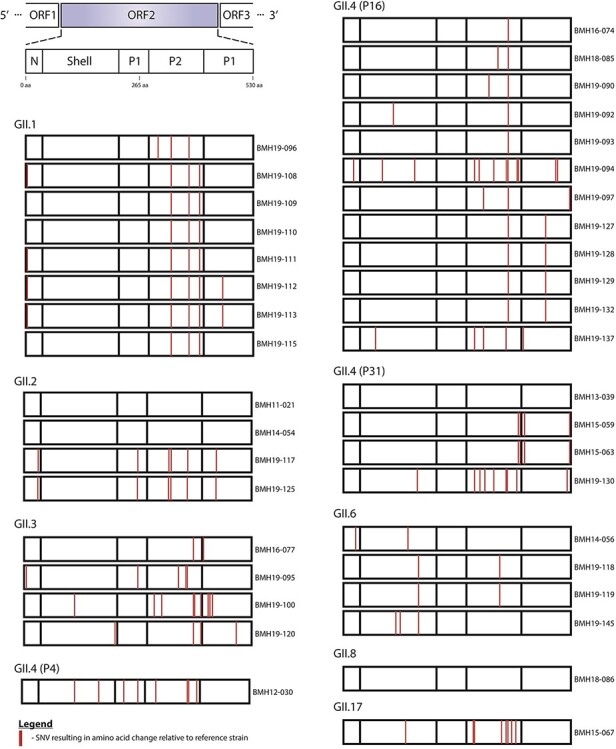

3.5. Variant analysis

The structural domains of the capsid include an N-terminus, a highly conserved shell, and two protruding spike domains (P1 and hypervariable P2) (Debbink et al., 2012; Smith and Smith 2019). The capsid protein is a major target for the host immune system. Consequently, certain changes within the antigenic determinants of the capsid protein could lead to antigenic diversification and host immune evasion (Lindesmith et al., 2013; Kendra et al., 2021). To investigate potential capsid protein variations in the norovirus samples, SNV analysis was conducted for each strain using highly similar GenBank references (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table S3). From Fig. 5, the majority of the SNVs resulting in amino acid changes were observed in the P2 domain. This trend was observed for all of the genotypes in this study. For GII.1, the linked outbreak samples BMH19-108, BMH19-109, BMH19-110, BMH19-111, BMH19-112, and BMH19-113 all have changes in the P2 domain at T325M, H374Q, and N293S relative to the reference strain (GenBank accession MK753033). While N293S seems to be present in many GII isolates including AHV83708 and AGI96399, we could not find any evidence for T325M and H374Q in the GenBank database. Interestingly, I453V in the P1 domain was only observed in BMH19-112 and BMH19-113 and not in the rest of the linked samples. BMH19-117 and BMH19-125, samples from genotype GII.2, showed changes in the N-terminus (S24N), P1 (V256I), P2 (V319I, V335I, and V373I), and P1 (V440I) (GenBank accession KJ407074). The majority of samples (17/39) in this study belong to the GII.4[P16] genotype (BMH16-074, BMH18-085, BMH19-090, BMH19-092, BMH19-093, BMH19-094, BMH19-097, BMH19-127, BMH19-128, BMH19-129, BMH19-132, and BMH19-137) and, with the exception of BMH19-137, contain a common V377A change in the P2 domain relative to the reference strain (GenBank accession MK762635). This biochemically conserved change has been reported in many isolates in the GenBank including AGS08159 and ATI15266. The norovirus GII.6 strains BMH19-118, BMH19-119, and BMH19-145 all have an S174P change in the conserved shell domain, as well as a G354Q variation in the P2 domain of BMH19-118 and BMH19-119 (GenBank accession MT731279). These changes have been reported in many isolates including AHI59154 and ADR30514.

Figure 5.

SNV analysis of norovirus ORF2 major capsid region. Norovirus de novo assemblies were assessed for variants relative to highly similar NCBI reference sequences. Schematic representation of the norovirus ORF2 region is shown (upper left). SNVs that resulted in non-synonymous amino acid changes are shown (red lines) at corresponding amino acid positions in the N-terminal, Shell, P1 and P2 domains for each isolate. Isolates are grouped by capsid genotype. The GenBank reference Isolates (accession numbers in brackets) used were GII.1-2016-USA (MK753033), GII.2-2011-USA (KJ407074), GII.3-2015-USA (MT409884), GII.3-2015-UK (MH218671), GII.4-2011-USA (KC576912), GII.4-2017-USA (MK762635), GII.4-2015-Canada (KX158279), GII.6-2018-USA (MT731279), GII.8-2018-China (MN996298) and GII.17-2016-China (KU757046).

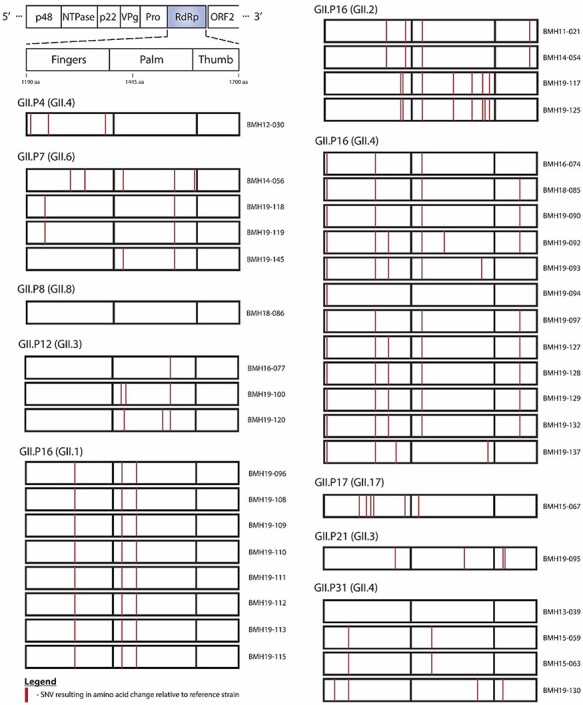

The norovirus RdRp (NS7) is the core enzyme for RNA replication. Its structure is highly similar to those of other positive-strand RNA viruses and can be described as a partially closed right hand, with fingers, thumb, and palm subdomains (Deval et al., 2017). The fingers and palm domains interact to form a channel. Within this channel, there are seven conserved motifs named A–G, which interact with the template, the nascent RNA, and the NTPs for RNA synthesis and comprise the active site (Deval et al., 2017). As shown in Fig. 6, the majority of the SNVs resulting in amino acid changes in RdRP were observed in the fingers and the palm domains. Also, as previously mentioned, GII.P16 was the dominant polymerase type, associated with three capsid genotypes: GII.4, GII.2, and GII.1. Similar to what has been observed for the VP1 protein, the linked outbreak samples BMH19-108, BMH19-109, BMH19-110, BMH19-111, BMH19-112, and BMH19-113 all have the same changes in the fingers and palm domains at T1294S, S1401T, and V1446A relative to the reference strain (GenBank accession MK753033) (Supplementary Table S4). The K1646R substitution is one of the few amino acid changes in the thumb domain that was observed in the majority of the GII.4[P16] isolates, while the S1401T change in the palm domain was observed for most GII.P16 isolates regardless of the capsid genotype (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table S4).

Figure 6.

SNV analysis of norovirus RdRP (polymerase) region. Norovirus de novo assemblies were assessed for variants relative to highly similar NCBI reference sequences. Schematic representation of the norovirus RdRP region is shown (upper left). SNVs that resulted in non-synonymous amino acid changes are shown (red lines) at corresponding amino acid positions in the fingers, palm and thumb domains for each isolate. Isolates are grouped by polymerase type. The GenBank reference isolates (accession numbers in brackets) used were GII.P4-2011-USA (KC576912), GII.P7-2018-USA (MT731279), GII.P8-2018-China (MN996298), GII.P12-2015-USA (MT409884), GII.P16-2016-USA (MK753033), GII.P16-2011-USA (KJ407074), GII.P16-2017-USA (MK762635), GII.17-2016-China (KU757046), GII.P21-2015-UK (MH218671) and GII.P31-2015-Canada (KX158279).

Intra-host variant analysis using long reads was limited to three of the thirty-nine norovirus genomes (Supplementary Table S5); however, putative variants were identified in the ORF2 N-terminus of BMH13-039 (P31L, GII.4 strain, subtype Sydney 2012), as well as GII.P16 sample BMH19-129 in ORF1 (E1360R) and ORF3 (R153Q) (Supplementary Table S5).

4. Discussion

The approach implemented by Parra and colleagues for full-length amplicon generation of GII samples has the potential to revolutionize the genome analysis of noroviruses. This method has recently been employed to obtain full-genomic sequences from hundreds of archival samples since the 1970s (Tohma et al., 2021). Herein, we applied a modified version of this approach on 57 norovirus GII-positive samples and obtained full-length amplicons for 39 samples (>67 per cent). We performed Sanger sequencing to determine the genotype of the remaining samples. The failure of these samples to generate full amplicons could be explained by the presence of RT-PCR inhibitors as the viral titre for these samples are above the limit of the assay. For future applications, diluting the samples could potentially reduce the effect of RT-PCR inhibitors and aid in obtaining full-length amplicons (Nasheri et al., 2020). We have also determined the lowest viral RNA load that would render full-genomic amplicons for four representative samples and demonstrated that 170–346 genome copies would be enough for WGS using this technique. This is promising as the level of natural contamination for certain high-risk foods, such as oysters, is within or even higher than this range (Le Guyader et al., 2009). Therefore, this approach has the potential to be employed for WGS analysis of naturally contaminated food products in the absence of an enrichment strategy (Nasheri, Vester, and Petronella 2019).

The difference between the approach used for sequencing in this study and the method employed by Parra and colleagues is that we did not perform amplicon purification for size selection; nevertheless, we obtained full-genomic sequences for all the full-length amplicons that were subjected to Illumina and Nanopore sequencing. Amplicon purification is often laborious, especially if applied to a large number of samples. Herein, we demonstrated that this step could be skipped without sacrificing the quality of the obtained sequences.

Coverage analysis of norovirus genomes demonstrated the utility of combining long-read Nanopore and short-read Illumina sequencing data to obtain full-length de novo norovirus genomes. Using an approach that consisted only of Illumina sequencing, we often obtained incomplete genome assemblies. Indeed, decreased sequencing coverage at the 5ʹ and 3ʹ ends of the norovirus sequence is observed for the Illumina data (Fig. 3), resulting in partial assembly for ORF1 and, less frequently, ORF3. By using a combined genome assembly approach, we were able to obtain highly accurate complete norovirus genomic sequences by first extracting full-length Nanopore sequence reads followed by error correction using a combination of both long- and short-read sequencing data. Differences in coverage depth along the genomes that are observed in some of the samples (Fig. 3) are likely the result of incomplete cDNA synthesis (partial genome length amplicons) or the presence of subgenomic sequences.

In recent years, the emergence and spread of RdRp/capsid recombinant noroviruses have been reported around the world. In the USA, a new recombinant GII.4 Sydney emerged in 2015 (GII.4 Sydney[P16]) and replaced the 2012 variant (GII.4 Sydney[P31], formerly GII.Pe-GII.4 Sydney), which was the dominant strain for several years throughout the world (Barclay et al., 2019). In Alberta, Canada, GII.4 Sydney[P16] was predominant in 2015–6 and 2017–8 (Hasing et al., 2019), GII.2[P16] was predominant in 2016–7 (Hasing et al., 2019), and GII.12[P16] emerged in 2018–9 and caused 10 per cent of outbreaks and 17 per cent of sporadic cases (Pabbaraju et al., 2019). Herein, despite the small sample size, GII.4 Sydney[P16] has made up the majority (43.3 per cent) of the tested samples in 2016–9, consistent with what has been reported in the literature for this period (Hasing et al., 2019). Although a combination of other genotypes, such as GII.3[P12], GII.1[P16], and GII.6[P7], was co-circulating at this time, GII.4 isolates were only associated with GII.P16 (Supplementary Table S1). It was also interesting to detect the GII.17[P17] strain that caused several outbreaks in multiple countries during 2014 and 2015 (van Beek et al., 2018; Matsushima et al., 2019) from a sample that was isolated in 2015 (Supplementary Table S1).

Even though GII.P16 has recently re-emerged as the dominant polymerase type, the oldest isolate in this study, BMH11-021, also has P16, but it does not cluster with the recent isolates; instead, it shows identity to older P16 isolates from 2011 (Fig. 4A). On the other hand, more recent GII.4 isolates from 2019 still show high identity to the older isolates from 2013, 2014, and 2015. This observation, together with the fact that GII.4 has continued to be the dominant genotype for more than three decades, indicates that despite some sequence plasticity, the GII.4 capsid is evolutionarily conserved due to some fitness advantages. The phylogenetic analyses in this study further confirm that epidemiologically linked isolates, such as BMH19-108 to BMH19-115 resulting from the GII.1[P16] outbreak, are highly similar across all three ORFs (Fig. 4) and, with the exception of I453V in the P1 domain of the VP1 protein, inter-host variation was not observed (Nasheri et al., 2017; Brown et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020).

The P2 subdomain of the VP1 protein interacts with potential norovirus carbohydrate receptors and contains seven antigenic epitopes, A–G (Debbink et al., 2012; Lindesmith et al., 2013; Tohma et al., 2019); therefore, it is not surprising to see that the majority of the non-synonymous SNVs are concentrated in this subdomain (Fig. 5). The GII.4 Sydney[P16] isolates in this study all contain the V377A change in the antigenic sites in the P2 subdomain (Supplementary Table S3) already described among GII.4 Sydney[P16] isolates in the USA (Cannon et al., 2017), which is absent in GII.4 Sydney[P31] isolates. In addition, BMH19-090 contains the M333V change in the epitope C of the P2 subdomain that was reported in GII.4 Sydney[P16] isolates in multiple studies (Cannon et al., 2017; Ruis et al., 2020). It has been suggested that these substitutions influence viral fitness by altering antigenicity and increasing transmissibility, receptor binding, or particle stability (Koromyslova and Hansman 2015; Lindesmith et al., 2019; Ruis et al., 2020; Kendra et al., 2021). Outbreak samples BMH19-127 to BMH19-132 have an S470T within the P1 subdomain that has not been reported before. GII.2[P16] strains have been reported in the last decade, and the S24N and V335I substitutions observed in the isolates in this study have been detected before (Tohma et al., 2017). However, V256I, V319I, V373I, and V440I substitutions were only observed in the samples from this study (Supplementary Table S3), and they are considered biochemically conserved substitutions.

The re-emerging P16 isolated in this study was associated with three capsid genotypes: GII.4, GII.2, and GII.1 (Fig. 6). The outbreak-associated GII.P16 (GII.1) isolates all have the same three substitutions T1294S, S1401T, and V1446A (Supplementary Table S4). However, the S1401T substitution in the palm domain was also observed in GII.P16 (GII.2) and GII.P16 (GII.4) isolates. Three out of four sporadic P31 isolates in this study, which are associated with the GII.4 Sydney capsid, had R1236K substitution in the fingers domain. The GII.P12 isolates all have the V1521I substitution, and all the GII.P7 isolates have the I1519V substitution within the palm domain; however, none of these substitutions falls within the conserved motifs or the active sites, and they are all considered biochemically conserved substitutions; thus, their significance is not known.

While variant analysis using long-read data was limited to three out of thirty-nine norovirus samples (Supplementary Table S5), putative variants were identified for BMH19-129 (ORF1 E1360R and ORF3 R153Q) and BMH13-039 (ORF2 P31L) (Supplementary Table S5). We did not find any precedent for ORF1 R1360 (reference coordinates MK762635) in the GenBank. However, precedents exist for ORF3, Q153, and ORF2 L31. Long-read data sets for norovirus variant calling may be improved in future by removing other amplicons (norovirus subgenomic sequences and contaminating amplicons) and/or increased Nanopore read depths.

In conclusion, using full-length amplicons is an efficient and sensitive method for norovirus WGS analysis. Also, our results are consistent with other reports regarding the predominance of GII.4[P16] Sydney replacing the previous GII.4[P31] Sydney, indicating the enhanced fitness of the GII.4 Sydney capsid. Continued norovirus genomic surveillance will help in the understanding of norovirus evolutionary mechanisms and the identification of emerging variants, which ultimately aid in designing future norovirus vaccines and antivirals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Brent Dixon and Dr Ana Pilar from the Bureau of Microbial Hazards for kindly reviewing the manuscript and providing insightful comments and Ms Julie Shay for her assistance in bioinformatic analysis.

Contributor Information

Annika Flint, Genomics Laboratory, Bureau of Microbial Hazards, Health Canada, Ottawa, ON, Canada.

Spencer Reaume, National Food Virology Reference Centre, Bureau of Microbial Hazards, Health Canada, Ottawa, ON, Canada.

Jennifer Harlow, National Food Virology Reference Centre, Bureau of Microbial Hazards, Health Canada, Ottawa, ON, Canada.

Emily Hoover, Genomics Laboratory, Bureau of Microbial Hazards, Health Canada, Ottawa, ON, Canada.

Kelly Weedmark, Genomics Laboratory, Bureau of Microbial Hazards, Health Canada, Ottawa, ON, Canada.

Neda Nasheri, National Food Virology Reference Centre, Bureau of Microbial Hazards, Health Canada, Ottawa, ON, Canada; Department of Biochemistry, Microbiology and Immunology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data is available at Virus Evolution online.

Funding

This study is financially supported by the Bureau of Microbial Hazards, Health Canada.

Conflict of interest:

None declared.

References

- Barclay L. et al. (2019) ‘Emerging Novel GII.P16 Noroviruses Associated with Multiple Capsid Genotypes’, Viruses, 11.doi: 10.3390/v11060535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch S. M. et al. (2016) ‘Global Economic Burden of Norovirus Gastroenteritis’, PLoS One, 11: e0151219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. R. et al. (2019) ‘Norovirus Transmission Dynamics in a Pediatric Hospital Using Full Genome Sequences’, Clinical Infectious Diseases, 68: 222–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull R. A. et al. (2020) ‘Analytical Validity of Nanopore Sequencing for Rapid SARS-CoV-2 Genome Analysis’, Nature Communications, 11: 6272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon J. L. et al. (2019) ‘Impact of Long-Term Storage of Clinical Samples Collected from 1996 to 2017 on RT-PCR Detection of Norovirus’, Journal of VirologicalMethods, 267: 35–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ——— et al. (2017) ‘Genetic and Epidemiologic Trends of Norovirus Outbreaks in the United States from 2013 to 2016 Demonstrated Emergence of Novel GII.4 Recombinant Viruses’, Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 55: 2208–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cates J. E. et al. (2020) ‘Recent Advances in Human Norovirus Research and Implications for Candidate Vaccines’, ExpertReview ofVaccines, 19: 539–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. et al. (2018) ‘Fastp: An Ultra-Fast All-In-One FASTQ Preprocessor’, Bioinformatics, 34: i884–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhabra P. et al. (2019) ‘Updated Classification of Norovirus Genogroups and Genotypes’, Journal of General Virology, 100: 1393–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotten M. et al. (2014) ‘Deep Sequencing of Norovirus Genomes Defines Evolutionary Patterns in an Urban Tropical Setting’, Journal of Virology, 88: 11056–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Coster W. et al. (2018) ‘NanoPack: Visualizing and Processing Long-Read Sequencing Data’, Bioinformatics, 34: 2666–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Graaf M., van Beek J., and Koopmans M. P. (2016) ‘Human Norovirus Transmission and Evolution in a Changing World’, Nature Reviews Microbiology, 14: 421–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deatherage D. E., and Barrick J. E. (2014) ‘Identification of Mutations in Laboratory-Evolved Microbes from Next-Generation Sequencing Data Using Breseq’, Methods in Molecular Biology (Clifton, N.J.), 1151: 165–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debbink K. et al. (2012) ‘Genetic Mapping of a Highly Variable Norovirus GII.4 Blockade Epitope: Potential Role in Escape from Human Herd Immunity’, Journal of Virology, 86: 1214–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deval J. et al. (2017) ‘Structure(s), function(s), and inhibition of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of noroviruses’, Virus Research, 234: 21–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green K. Y. (2013) ‘Caliciviridae: The Noroviruses’. In: Knipe D. M., and Howley P. M. (eds.) Fields Virology, p. 948. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Hasing M. E. et al. (2019) ‘Changes in Norovirus Genotype Diversity in Gastroenteritis Outbreaks in Alberta, Canada: 2012–2018’, BMCInfectious Diseases, 19: 177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosomichi K. et al. (2014) ‘A Bead-Based Normalization for Uniform Sequencing Depth (Benus) Protocol for Multi-samples Sequencing Exemplified by HLA-B’, BMC Genomics, 15: 645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama K. et al. (2002) ‘Phylogenetic Analysis of the Complete Genome of 18 Norwalk-Like Viruses’, Virology, 299: 225–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendra J. A. et al. (2021) ‘Antigenic Cartography Reveals Complexities of Genetic Determinants that Lead to Antigenic Differences among Pandemic GII.4 Noroviruses’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118.doi: 10.1073/pnas.2015874118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koromyslova A. D., and Hansman G. S. (2015) ‘Nanobody Binding to a Conserved Epitope Promotes Norovirus Particle Disassembly’, Journal of Virology, 89: 2718–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroneman A. et al. (2011) ‘An Automated Genotyping Tool for Enteroviruses and Noroviruses’, Journal of Clinical Virology, 51: 121–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Guyader F. S. et al. (2009) ‘Detection and Quantification of Noroviruses in Shellfish’, Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 75: 618–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindesmith L. C. et al. (2019) ‘Human Norovirus Epitope D Plasticity Allows Escape from Antibody Immunity without Loss of Capacity for Binding Cellular Ligands’, Journal of Virology, 93.doi: 10.1128/JVI.01813-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ——— et al. (2013) ‘Emergence of a Norovirus GII.4 Strain Correlates with Changes in Evolving Blockade Epitopes’, Journal of Virology, 87: 2803–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D. P. et al. (2015) ‘RDP4: Detection and Analysis of Recombination Patterns in Virus Genomes’, Virus Evolution, 1: vev003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushima Y. et al. (2019) ‘Evolutionary Analysis of the VP1 and RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase Regions of Human Norovirus GII.P17-GII.17 In 2013-2017’, Frontiers in Microbiology, 10: 2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzel P., Ng K. L., and Krogh A. (2016) ‘Fast and Sensitive Taxonomic Classification for Metagenomics with Kaiju’, Nature Communications, 7: 11257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasheri N. et al. (2020) ‘Evaluation of Bead-Based Assays in the Isolation of Foodborne Viruses from Low-Moisture Foods’, Journal ofFoodProtection, 83: 388–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ——— et al. (2017) ‘Characterization of the Genomic Diversity of Norovirus in Linked Patients Using a Metagenomic Deep Sequencing Approach’, Frontiers in Microbiology, 8: 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasheri N., Vester A., and Petronella N. (2019) ‘Foodborne Viral Outbreaks Associated with Frozen Produce’, Epidemiology and Infection, 147: e291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pabbaraju K. et al. (2019) ‘Emergence of a Novel Recombinant Norovirus GII.P16-GII.12 Strain Causing Gastroenteritis, Alberta, Canada’, Emerging Infectious Diseases, 25: 1556–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra G. I. (2019) ‘Emergence of Norovirus Strains: A Tale of Two Genes’, VirusEvolution, 5: vez048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra G. I., and Green K. Y. (2015) ‘Genome of Emerging Norovirus GII.17, United States, 2014’, Emerging Infectious Diseases, 21: 1477–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra G. I. et al. (2017) ‘Static and Evolving Norovirus Genotypes: Implications for Epidemiology and Immunity’, PLoSPathogens, 13: e1006136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petronella N. et al. (2018) ‘Genetic Characterization of Norovirus GII.4 Variants Circulating in Canada Using a Metagenomic Technique’, BMCInfectious Diseases, 18: 521-018-3419-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riaz N. et al. (2021) ‘Adaptation of Oxford Nanopore Technology for Hepatitis C Whole Genome Sequencing and Identification of Within-Host Viral Variants’, BMC Genomics, 22: 148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruis C. et al. (2020) ‘Preadaptation of Pandemic GII.4 Noroviruses in Unsampled Virus Reservoirs Years before Emergence’, VirusEvolution, 6: veaa067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shean R. C. et al. (2019) ‘VAPiD: A Lightweight Cross-Platform Viral Annotation Pipeline and Identification Tool to Facilitate Virus Genome Submissions to NCBI GenBank’, BMC Bioinformatics, 20: 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith H. Q., and Smith T. J. (2019) ‘The Dynamic Capsid Structures of the Noroviruses’, Viruses, 11.doi: 10.3390/v11030235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K. et al. (2013) ‘MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 6.0’, Molecular Biology and Evolution, 30: 2725–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teunis P. F. et al. (2015) ‘Shedding of Norovirus in Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Infections’, Epidemiology and Infection, 143: 1710–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohma K. et al. (2017) ‘Phylogenetic Analyses Suggest that Factors Other than the Capsid Protein Play a Role in the Epidemic Potential of GII.2 Norovirus’, mSphere, 2.doi: 10.1128/mSphereDirect.00187-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ——— et al. (2019) ‘Population Genomics of GII.4 Noroviruses Reveal Complex Diversification and New Antigenic Sites Involved in the Emergence of Pandemic Strains’, mBio, 10.doi: 10.1128/mBio.02202-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ——— et al. (2021) ‘Genome-Wide Analyses of Human Noroviruses Provide Insights on Evolutionary Dynamics and Evidence of Coexisting Viral Populations Evolving under Recombination Constraints’, PLOSPathogens, 17: e1009744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Beek J. et al. NoroNet . (2018) ‘Molecular Surveillance of Norovirus, 2005–16: An Epidemiological Analysis of Data Collected from the NoroNet Network’, TheLancetInfectious Diseases, 18: 545–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viehweger A. et al. (2019) ‘Direct RNA Nanopore Sequencing of Full-Length Coronavirus Genomes Provides Novel Insights into Structural Variants and Enables Modification Analysis’, GenomeResearch, 29: 1545–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker B. J. et al. (2014) ‘Pilon: An Integrated Tool for Comprehensive Microbial Variant Detection and Genome Assembly Improvement’, PLoS One, 9: e112963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. F. et al. (2020) ‘Characterization of a Hospital-Based Gastroenteritis Outbreak Caused by GII.6 Norovirus in Jinshan, China’, Epidemiology and Infection, 148: e289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The complete de novo genome sequences of the 39 norovirus isolates used in this study have been uploaded to the GenBank under accession numbers: Y18883 to MW661284. All SRAs are available in the GenBank under BioProject ID PRJNA713985.