Abstract

Introduction

Financial stress, social stress and lack of support at home can precipitate domestic and child abuse (World Health Organization, 2020). These factors have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic (NSPCC, 2020b) (NSPCC, 2020a). We hypothesise an increase in Bridgend's domestic and child abuse during lockdown.

Method

Data was collected retrospectively from 23rd March to 30th September 2020 and compared to the same time period in 2019. Wales-wide data on domestic abuse was shared by the Welsh Government's Live Fear free helpline. Local data was shared by domestic abuse charity CALAN, the Emergency Department (ED) and Paediatric Department of Princess of Wales Hospital (POWH).

Results

During lockdown, Live Fear Free reported increasing average monthly contact across Wales in 2020 (511 April; 631 December). Locally, CALAN reported a 190% increase in self-referrals and a 198% increase in third party referrals, but there was a 36% decrease in referrals from Police for domestic abuse.

The Paediatric Department observed a 67% decrease in child protection medical examinations (CPMEs) undertaken (52 vs. 17). 23 examinations in 2019 were referred from schools compared to 1 in 2020. There was a greater proportion of self-referrals for CPMEs in 2020. ED child protection referrals increased from 189 (2019) to 204 (2020).

Conclusion

There was an increase in self-referrals to local support services for domestic and child abuse concerns and an increase in referrals from families/friends for child protection concerns. This was not the case with police, ED and schools/nurseries referrals. This suggests reduced engagement with public sector organisations during lockdown which services should consider.

Keywords: COVID-19, Lockdown, Child abuse, Neglect, Domestic abuse

1. Introduction

Child maltreatment constitutes abuse and neglect and can exist in many forms. This can include: physical, emotional and and sexual abuse which can impact a child's health and development (WHO, 2020). Globally the burden of violence against children is high; (Hills et al., 2016) estimated that around 1 billion children and young people have experience abuse of some form each year. Similarly, domestic violence and violence against women is a global issue. It can be defined as a ‘pattern of behaviour in any relationship that is used to gain or maintain power and control over an intimate partner.’ Latest data suggest that globally one third of women have experienced violence by a partner (UN., 2020). In the UK, an accurate prevalence of child abuse is difficult to ascertain as many cases are unreported (May-Chahal & Cawson, 2005). Latest data estimates one in five adults have experienced child abuse (ONS, 2020a). Prior to the COVID pandemic, an estimated 2.3 million adults had experienced domestic violence in the last year in England and Wales (ONS., 2020b).

There is evidence that child abuse and domestic abuse often co-exist in families and thus can be a strong predictor of each other (McKay, 1994). There are several known factors which can predispose both child abuse and domestic abuse. The CDC categorise risk factors for child abuse and neglect into: individual factors, family factors and community factors (CDC., 2021). Individual factors can include drug or alcohol abuse (Jaudes et al., 1995), mental health issues, economic issues or parenting stress. Family factors can include isolation or family violence. Whereas, community factors can include unstable housing, unemployment, or poverty. These may all impact on parental capacity (Cleaver et al., 2011) and therefore may disrupt their ability to provide a nurturing home environment for the child. Protective factors can include access to care or access to activities, school and strong social support networks. Similarly, domestic violence prevalence is higher where there is unemployment (Kyriacou et al., 1999), where the perpetuator has a history of drug or alcohol abuse (Christoffersen & Soothill, 2003) and is often recurrent (Berrios & Grady, 1991).

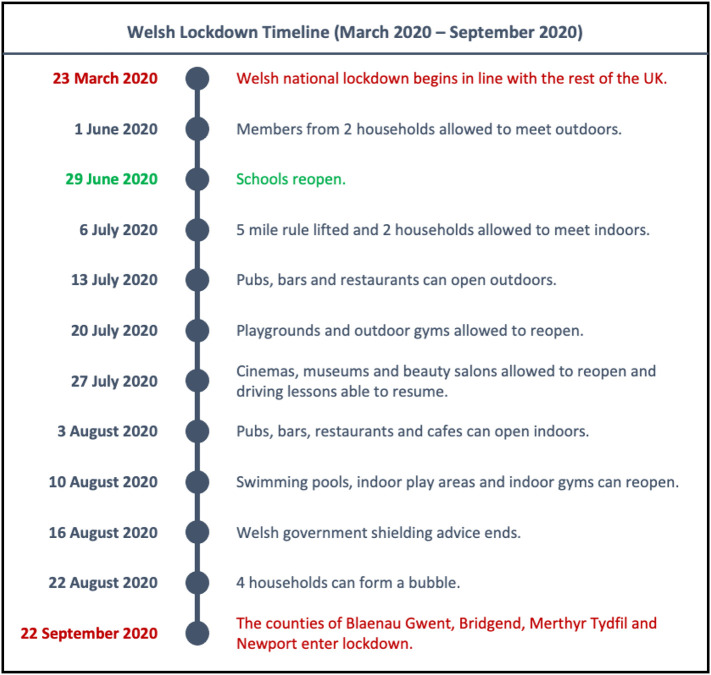

On the 23rd March 2020, the UK government enforced a national lockdown to reduce the threat of the COVID-19 global pandemic (Fig. 1 ). Since then, the population has faced months of fluctuating levels of restrictions, including school closures, and enforced working from home. This has had a wide impact on daily life and introduced stressors, economically, socially and within families (Douglas et al., 2020). Non-essential businesses were closed and many people faced unemployment. Schemes such as the ‘Coronavirus Job retention scheme’ or where employees were temporarily furloughed were set up in the UK to avoid redundancies. This scheme has been extended many times and latest data suggest that 11.2 million jobs were supported due to the scheme so far (HMRC, 2021).

Fig. 1.

Timeline of COVID-19 restrictions within Wales from the 23rd March 2020 to September 2020.

Social stressors, financial stressors and changes to support networks are known risk factors for domestic and child abuse. There were reports of increased unemployment rates throughout the pandemic period, (Leaker, 2021) which were highest at the initial onset of the pandemic. The recovery of this has been slow. Social restrictions resulted in isolation from family and friends (NSPCC, 2020b). Increased stress levels, mental health issues and alcoholism have also been reported (Brown et al., 2020). In particular, there has been much discussion regarding the significant mental health impact as a result of the pandemic on the population (Rajkumar, 2020). In addition, there have been reports of increased alcohol and substance abuse (Aldridge et al., 2021; Pollard et al., 2020). Alongside this, there has been a disruption in factors known to be protective against child abuse including; steady parental employment, support networks from adults outside of the family and friendships, as well as disruption of protective services (Banerjee & Rai, 2020). In addition, with restricted access to the traditional sources of referrals for safeguarding concerns such as schools during lockdowns and closure of usual activities there is concern about protecting vulnerable children.

In addition, this has been evidence that the impact of COVID-19 in the UK has also widened pre-existing healthcare inequalities (Marmot et al., 2020) and amplified unemployment, housing and educational issues. There has also been evidence that a sudden change in circumstances such as through national emergencies and natural disasters, can precede an increase in household violence (Seddighi et al., 2019). Therefore, there is a risk that the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated several risk factors that can predispose to child abuse and domestic violence. This has led to concern about the potential for increased incidence during the lockdown period (Lawson et al., 2020).

In Wales, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, The Rights of Children and Young Persons (Wales) Measure 2011, formally adopted the convention of the UN Convention on Rights of the Child (UN, 1989) which maintains the importance of protecting children against all forms of violence and ensuring access to food, housing and safety. Further to this, the Children Act 2004 describes promoting the welfare of children. Children and young people in Wales are protected by the The Social Services and Well-being (Wales) Act 2014. The Wales Safeguarding Procedures outlines the duty and responsibility to raise a concern about abuse, neglect or harm.

During COVID-19, the Welsh Government highlighted the role of educational settings to have a revised safeguarding policy in light of the changing situation, alongside the established safeguarding lead. Policies were put into place to ensure that children who were eligible for Free School Meals were able to have these delivered. To reduce transmission of the virus and ensure critical staff were able to attend work, school provision was made in schools ‘hubs’ for children of keyworkers and vulnerable children. Additionally, emergency legislation meant that local authorities and social care services had changed responsibility in assessing children at risk. Similarly, other social and healthcare services shifted services to more remote based approaches to reduce the risk of transmission.

There has been evidence of domestic violence prevalence increasing during the COVID-19 pandemic and more individuals reaching out to support services in the UK (Women's Aid, 2020). They also report that many women have reported: increased isolation, increased mental health issues, worsening abuse, limited refuge spaces and perpetrator using restrictions to control access to support during the lockdown period (Bradbury-Jones & Isham, 2020; Roesch et al., 2020). In addition, greater time spent at home with limited permitted reasons to leave increases the time spent between perpetrators and victims of both child and domestic abuse, with restricted ability to escape violence and seek help (Sacco et al., 2020).

However, others have also suggested cases of abuse may have been missed due to restricted access to protective public services during lockdown (Caron et al., 2020). Similarly, there have been reports of increased contact with child abuse helplines nationally (NSPCC, 2020a). However, there are also reports of reduced contact with public sector organisations such as schools, hospitals and emergency services in the UK (Lynn et al., 2021). Therefore, there may have been a disparity between incidence reported from helplines compared to those from public services. This has further significance for informing future policy surrounding protective public services during lockdowns.

This increase in stressors and home environment described above coupled with the shift in usual safeguarding services, makes one postulate that there may have been an increase in domestic and child abuse during lockdown. This study investigates the hypothesised increased incidence of domestic and child abuse specifically within Bridgend County during the initial COVID-19 lockdown period from 23rd March 2020 until 30th September 2020.

This paper focuses on Bridgend County, South Wales. The Welsh Deprivation Index is a tool used in Wales to help identify the most deprived areas with respect to 8 domains: income, employment, health, education, access to services, housing, community safety, physical environment (Welsh Government, 2019). Bridgend County shows an overall deprivation of 30–50% and one of Bridgend's towns – Caerau fall under within the top 5 most deprived areas across Wales.

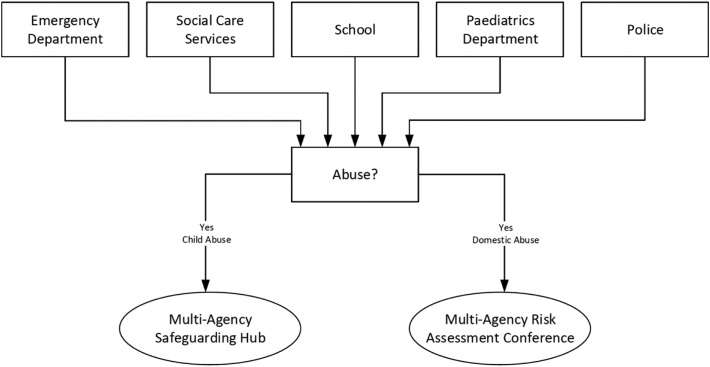

In Bridgend, domestic violence referrals to domestic violence support services (such as MARAC) may come from public sector organisations and charities. Child abuse concerns are referred from predominantly schools, hospitals, police and and third-party referrals to the MASH (Multi-Agency Safeguarding Hub) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Diagram representing usual Safeguarding pathways in Bridgend County.

This research question is important as there is little literature regarding incidence of child abuse or domestic abuse during the COVID-19 lockdown period in Wales. Furthermore, this issue has wider importance as research has shown that adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) can affect the wellbeing of children throughout life (Bellis et al., 2015). Child maltreatment and household dysfunction are recognised as adverse childhood experiences (Riley et al., 2019) which have been shown to increase health-harming behaviours both immediately and long-term across a child's life course (Hughes et al., 2016). ACEs have been reported to increase health-harming behaviours such as substance misuse, increase mental health issues and chronic diseases including diabetes and cancer (Ashton et al., 2016) and have been linked to greater healthcare use in adult life (Chartier et al., 2010). Therefore, understanding more about the incidence of child abuse and domestic abuse in Wales can help us build a picture of the lockdown landscape and inform future policy surrounding protective public services during lockdowns.

1.1. Objective

This study investigates the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the incidence of domestic abuse and child abuse in Bridgend by comparing data from 2019 and 2020. Following on from this, it is also envisaged that this will aid understanding of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on safeguarding concerns in Bridgend.

To answer this question, data from known sources of referrals for domestic abuse and child abuse concerns in Bridgend were analysed. This included: public sector organisations, schools and charities. The aim was to observe any trend in the incidence of domestic violence and child abuse or safeguarding concerns in Bridgend. There was a particular focus on the total number and source of referrals during lockdown.

It also must be acknowledged that schools play a fundamental role in protecting children and that this may have been hindered with school closure. Views from local schools were also sought on the impact of school closures on safeguarding children during lockdown.

2. Method

Data was collected retrospectively from domestic abuse charities, healthcare departments and schools in Bridgend from the 23rd March to 30th September 2020 and compared to the same time period in 2019. This time period was selected to cover the initial lockdown period to the easing and further re-implementation of restrictions. Data preceding 2019 was unavailable.

Our primary outcomes were to evaluate the incidence of domestic abuse or child abuse in Bridgend. Secondary data was obtained from a range of data sources to assess the incidence and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in Bridgend. This included: local domestic abuse charities, hospital departments and schools.

More specifically, the numbers of contacts from a national domestic violence charity (Live Fear Free Helpline) were evaluated alongside the number of referrals made to a local Bridgend Domestic abuse charity (CALAN). The number of referrals made from the Princess of Wales Hospital's Emergency Department to safeguarding interagency services - MARAC (Multi-Agency Risk Assessment Conference) and MASH (Multi-Agency Safeguarding Hub) were also analysed.

In addition, the numbers of Child Protection Medical Examinations from the Princess of Wales Hospital' s Paediatric Department during the study period were analysed.

Our secondary outcome was to evaluate the impact of the lockdown on schools and school-aged children through interviews with safeguarding leads of local schools.

All data collected was analysed using Microsoft Excel and no statistical models were used to analyse quantitative data. No ethical approval was required due to collection of secondary data.

2.1. Domestic abuse charities

Wales-wide data on domestic abuse was shared by the Live Fear free helpline (funded by the Welsh Government and provided by the national charity Welsh Women's Aid). The Live Fear free helpline is a confidential 24-h helpline available to provide help and support for those concerned about domestic abuse, sexual violence or other forms of violence. It was one of the key domestic abuse helplines in Wales offering a range of support including: signposting and counselling during the COVID-19 pandemic period (ONS, 2020c). Those who require support can make contact through phone, online chat, text or email.

Specifically, the total number of contacts to the charity (including phone calls, online instant messaging/web chat, emails and texts) month by month from April 2020 to September 2020, were shared with us. The primary data was collected by Live Fear Free helpline and shared by the Welsh Government.

Charity data was also obtained from CALAN. CALAN is one of the largest domestic abuse charities in Wales and is a key support service in the Bridgend County. Services include: crisis drop-in support, programme delivery for victims of domestic abuse, refuge services, risk assessment and long-term support with domestic abuse specialist workers. Primary data was collected by the Bridgend service manager from April 2019 to September 2019 and April 2020 to September 2020. The total number of all referrals to CALAN and a breakdown of the source of these referrals (self-referrals, third party referrals and police) was included. This data is routinely collected by the charity annually.

2.2. Health data

Data was collected from electronic patient records at the Princess of Wales Hospital's Emergency Department (ED) and the Paediatric Department. Access was granted by the safeguarding leads in each department. This data is routinely collected by the departments for audit purposes.

ED data was screened for records of patients who had a MARAC or MASH referral. These referrals would have been made by the healthcare professionals at the time of the ED assessment and then documented in the electronic notes. This would include referrals concerning domestic abuse, safeguarding concerns and information sharing (if a child is already known to social services). Specifically, data was collected regarding the number of referrals to MARAC and the number of referrals to MASH for the months of the study period. Additionally, each MASH referral was reviewed to identify: the number and age of children involved, as well as the reason for the safeguarding referral. The reasons for safeguarding referral were then categorised into: neglect & physical abuse, child mental health issues, parental mental health issues, information sharing, domestic violence concerns, child intoxication, observed behaviour in ED and other.

From the Paediatric Department data, the total number of child protection medical examinations (CPME) during the study period, was collected from patient records. Data was reviewed and anonymised data extraction was performed to extract demographics and original source of referral. CPME's are carried out by trained paediatricians to specifically look for signs of non-accidental injury and neglect. The number of children added to the child protection register during the study period was also recorded.

2.3. Schools

Local primary and secondary school safeguarding representatives in the Bridgend County were contacted via phone call and email with a standardised questionnaire with 28.3% response rate. Consent was obtained.

This standardised questionnaire was agreed by all clinicians in the research team. Prior contacting schools, all clinicians reviewed and discussed questions to be asked to ensure consistency, and quality of data.

The questionnaire consisted of twenty-two semi-structured questions to gather qualitative information on their experiences of this time period. Schools were asked about the frequency of contact with pupils, any safeguarding concerns or referrals during lockdown and how they were handled, and any child protection strategies put in place by the school. Each interview lasted approximately twenty minutes. (See appendix).

Data was analysed using basic frequency analysis to ascertain the number of occurrences for each response. The results were then described.

3. Results

3.1. Domestic abuse charities

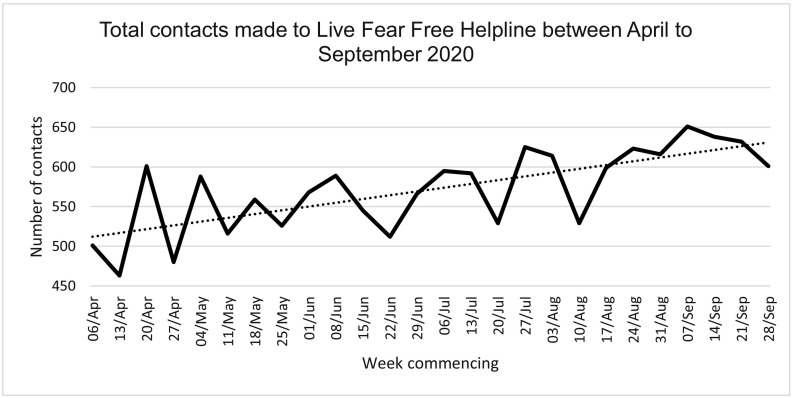

During lockdown, the national Wales Live Fear Free helpline, reported increased contact across the consecutive months of 2020 with an average of 511 contacts made in April increasing incrementally to 631 on average in September (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Total contacts made to Live Fear Free Helpline from April to September 2020 (includes calls, webchat, emails and texts).

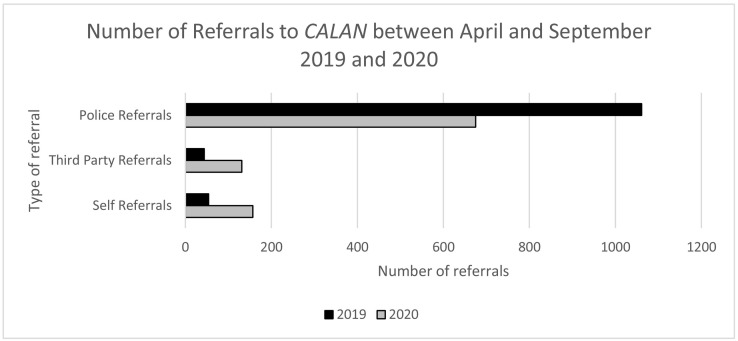

Local domestic abuse Charity; CALAN, reported an overall decrease in total referrals in 2020 compared to 2019 in the time period April to September. There were 1159 referrals in total made to CALAN in 2019 and 963 referrals made in 2019. However, the proportion of these that were self-referrals increased 190% from 54 in 2019 to 157 in 2020. There was a 198% increase in third party referrals from 44 in 2019 to 131 in 2020 (Fig. 4 ). However, there was a 36% decrease in referrals from police with 1061 referrals in 2019 and 675 in 2020.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of referrals made to Domestic abuse charity CALAN in 2019 and 2020 between April to September.

3.2. Health data

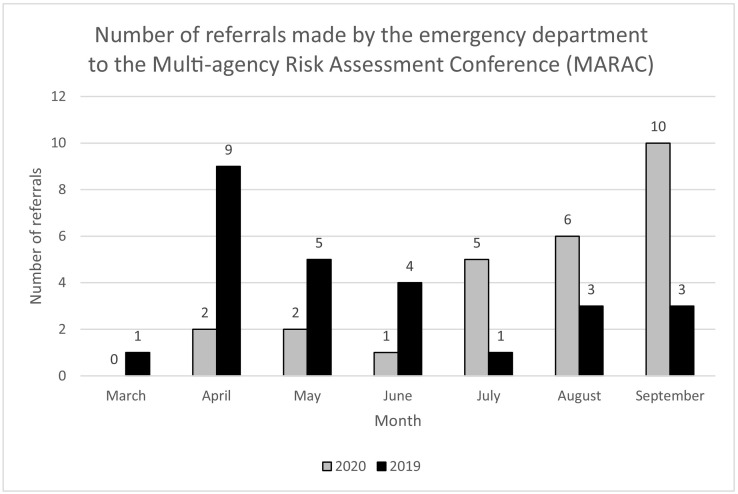

In the Emergency Department, there was no difference between the number of referrals for adults to a Multi-Agency Risk Assessment Conference (MARAC) for domestic violence concerns (MARAC) from ED (26 in both 2019 and 2020). However, a greater proportion of these referrals were made in the months where restrictions had eased (Fig. 5 ).

Fig. 5.

Number of referrals made each month by the emergency department to the Multi-agency Risk Assessment Conference (MARAC) between March–September 2020 compared to 2019.

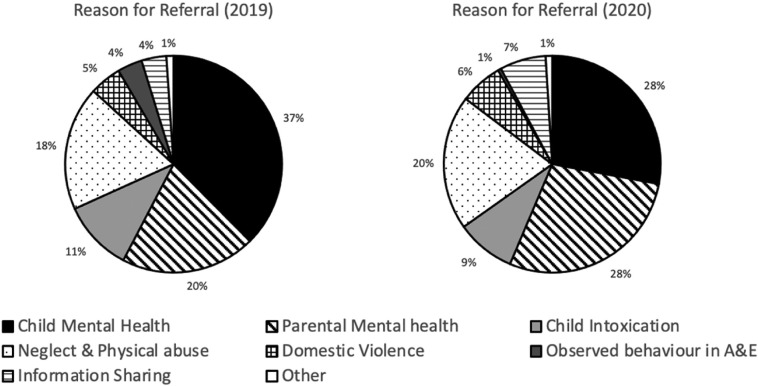

Referrals from the ED to the Multi-agency safeguarding hub (MASH) for child protection concerns increased from 189 (2019) to 204 (2020) within the time periods investigated, with an increase in children involved from 229 to 278 respectively.

There was an increased proportion of referrals from ED made due to neglect or physical abuse concerns in 2020 with 18.5% (35) in 2019 compared to 20.1% (41) in 2020 (Fig. 5, Fig. 6 ). There was an increase in referrals in 2020 for children who lived in the same household or had contact with a victim or perpetrator of domestic violence with 4.8% (9) in 2019 and 6.4% (13) in 2020.

Fig. 6.

Reasons for child protection referrals from the emergency department in the Princess of Wales hospital to MASH.

ED referrals for parental mental health, particularly overdose, also increased in 2020 with 20.1% (38) in 2019 and 28.4% (58) in 2020.

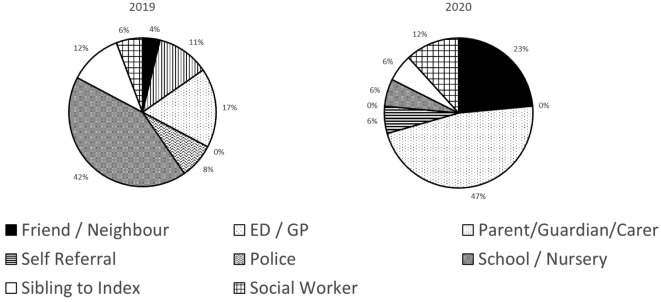

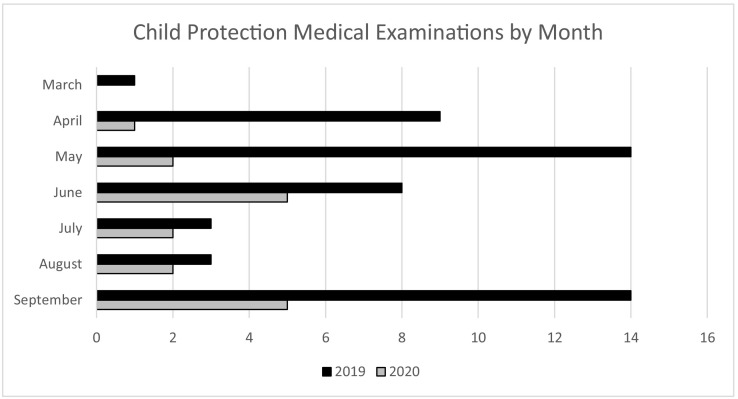

The Paediatric Department observed a 67% decrease in the number of child protection medical examinations (CPMEs) undertaken in 2020 (17) compared with 2019 (52).

The original sources of referrals differed between these years (Fig. 8). The numbers of referrals from parents/carers/family increased from 15.4% (8) in 2019 to 9 52.9% (9) in 2020. Referrals from neighbours/friends also made up a greater number of referrals from 3.8% (2) in 2019 to 17.6% (3) in 2020. Self-referrals also increased from (0%) 0 in 2019 to 5.9% (1) in 2020. However, there was a significant decrease in CPME referrals from schools and nurseries from 44.2% (23) in 2019 to only 5.9% (1) in 2020. No referrals were received from police or healthcare professions (emergency department and GPs) in 2020 with these making up 7.7% (4) and 11.5% (6) respectively of referrals in 2019. Referrals for children already known to social services made up a greater proportion of referrals, 76% (13) in 2020 compared to 44% (23) in 2019.

Fig. 8.

Source of referral for Child Protection Medical Examinations (CPME) performed in the Princess of Wales Paediatric Department in 2019 and 2020 (March–September).

The number of CPME referrals decreased in 2020 for all age brackets; pre-nursery (<3 years), nursery (3–5), primary school (6–11) and teenagers (12–18). The greatest proportion decrease of referrals was seen in the primary school age group making up 14 (27%) of referrals in 2019 but only 6% (1) in 2020. Referrals were highest in the pre-nursery age group in both years, making up 38.5% (20) of referrals in 2019 and increasing to 64.7% (11) of referrals in 2020 (Fig. 7 ).

Fig. 7.

Number of Child Protection Medical Examinations (CPME) performed each month in the POWH Paediatric department in 2019 and 2020 (between March to September).

The number of children added to the child protection register over the course of our study period (March–September) was also compared across both 2019 and 2020. There was a 23.6% decrease in the total number of additions to the child protection register in 2020 (140 in 2019 and 107 in 2020).

3.3. Schools

Completed questionnaires were received from 17 of the 60 Bridgend County schools contacted. Responses demonstrated that despite all having policies in place for monitoring pupils in lockdown, there was variability in both frequency and methods of contact. Of the schools included; 88% (15) stated they had a specific COVID-19 safeguarding policy in place. 53% (9) schools stated they contacted vulnerable pupils once a week and 18% (3) schools 2 or more times a week.

Whilst all schools made contact with their pupils during the lock-down period, contact methods were varied. In total, 59% (10) schools used phone calls, 53% (9) used virtual platforms, 4 used emails (23.5%), 6% (1) via face-to-face meetings and 11.8% (2) had unknown methods of contact.

Regarding the numbers of safeguarding cases identified by schools during the lockdown period; 18% (3) schools reported no safeguarding cases, 41% (7) schools stated that they reported 1–5 cases, 12% (2) schools reported between 6 and 10 cases and 2 schools (12%) reported over 11 cases. 18% (3) schools did not record this information. The comparison of these statistics from 2020 and previous years was not shared by any of the schools.

Bridgend schools also cited several barriers in keeping in contact with children including: lack of devices and both pupil and parent engagement. The impact of lockdown on their students was highlighted by schools, with the most common issues cited, being: wellbeing, mental health, academic and behavioural.

4. Discussion

During the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown period, between March 2020 and September 2020 there has been observed a shift in the home environment as well as increased social and financial stressors (Douglas et al., 2020). This would be expected to impact upon the incidence of child abuse and domestic abuse during the lockdown period. Several trends have been identified from the data, though we must acknowledge that we cannot draw conclusions regarding the absolute incidence of domestic and child abuse in Bridgend in the lockdown period.

The findings from this study suggest a shift in the source of referrals to domestic abuse charities and healthcare departments. A significant increase was seen in both self-referrals and third-party referrals in 2020. This included referrals to the local domestic abuse charity CALAN and referrals with child protection concerns from families and neighbours resulting in Child protection medical examinations (CPMEs) in the paediatric department. In contrast, there was a decrease in police referrals to domestic abuse charity CALAN in 2020 whilst referrals from public sector organisations remained the same.

Our findings are in agreement with other studies in the UK and globally. A study also observed an increase in domestic abuse calls to support services, mainly via third party reporting in the UK (Ivandic et al., 2020). Other studies such as (Barbara et al., 2020) noted an increase in contact to phone-counselling services but a decrease in in-person assistance from Domestic Violence Support centres at local hospitals in Italy, during the initial lockdown. Further to this, the NSPCC also reported an increase in contact made, especially online contact, from neighbours and friends compared to schools and traditional referral routes (NSPCC, 2020a). This change in the referral patterns for domestic abuse and child abuse concerns may be the result of reduced accessibility to, or engagement with, public sector organisations during lockdown. There is also the possibility of underreporting and thus it is difficult to ascertain the true incidence of domestic abuse and child abuse over the lockdown period.

CPMEs are a key part of safeguarding assessments for children and young people of concern. Our findings also suggest that there was also a significant decrease in CPMEs for school aged children. Health data from the Paediatric Department observed a 67% decrease in the number CPMEs undertaken in 2020 (17) compared with 2019 (52). Furthermore, this study found that there was a 23.6% decrease in the number of children added to the child protection register. This is in agreement with other UK studies. In Birmingham, (Garstang et al., 2020) also observed a decrease in CPME referrals especially from school staff. Similarly, in Newcastle (Bhopal et al., 2021) also noted a decrease in CPMEs compared to the preceding two years, and significantly this number was the lowest just after the initiation of the initial ‘lockdown’ in April 2020. However, despite a reduction in CPME assessments over the lockdown period, there is concern as UK studies have reported increases in suspected physical abuse, often of greater severity, during lockdown (Masilamani et al., 2020). This has included increase in reported physical abuse (Kovler et al., 2021) and abusive head trauma (Dyson et al., 2020; Sidpra et al., 2020). In particular, one study reported a 1439% increase in abusive head trauma cases within the first month of lockdown when compared to the prior three years (Sidpra et al., 2020).

However, it is worth noting that our findings do not support the marginal increase in referrals to MASH with child protection concerns from ED in Bridgend. Therefore, this data gives no strong evidence for an increase in Bridgend's child abuse during lockdown.

Together, there appears to be a mismatch between the reported increase in incidence of child abuse during the lockdown period and the number of referrals for assessments (CPMEs). These findings most likely reflect the change in school provision during the 2020 pandemic time period. In a broader context, schools play a central role in the safeguarding of young people; not only do they act as a safe place for vulnerable children, but education accounts for a significant proportion of referrals to social services. With school closures, and other usual safeguarding pathways disrupted due to the pandemic (Bhopal et al., 2021), there is concern that there may be ‘hidden’ cases of child abuse and neglect (Green, 2020).

We must acknowledge the likelihood that cases of child abuse will have been missed given the known increase in risk factors for child abuse during the lockdown and the reduction in identification with school closures and support services reduced.

This concern of ‘missed’ cases of child abuse over the lockdown period was also shared by teachers of local primary and secondary schools following discussions around the impact of the pandemic on children and young people in Bridgend. We found that the majority of schools kept in contact with pupils, although the regularity of this did vary. Some schools did report referring for safeguarding concerns during lockdown but also reported that some of these cases were for children already known to social services.

In addition, looking closely at the data from the Welsh Government funded Live Fear Free domestic abuse helpline, there was an increase in contact in 2020 as the months progressed and restrictions eased. Although the total number of referrals for domestic abuse concerns to the MARAC from ED in 2020 and 2019 were the same, the number of monthly referrals increased with subsequent months in 2020 compared to 2019, supporting the Wales wide trend. This highlights the potential latent effect of restrictions on the help sought for domestic violence. There was also an increased proportion of these referrals involving children in 2020. This should be taken into consideration with the further implementation and easing of restrictions.

The main strength of this study is the multi-agency data used from a range of sources such as health data, domestic abuse charities, and schools' data. Our study includes both qualitative for interviews with local schools and quantitative data from secondary data collected routinely from healthcare departments and local domestic abuse charities. The aim of this was to capture broader findings relating to the incidence and impact of child abuse and domestic abuse in Bridgend, Wales as a result of the lockdown.

However, there are several limitations of our study which must be acknowledged. Multiple local domestic abuse charities were contacted, however, we only received appropriate data from one charity: CALAN, meaning this may not represent the full picture of domestic abuse in Bridgend County. Using secondary data from external sources allows for potential bias in the data provided. We also received pre-analysed data from national charities without the raw data which we acknowledge affects the validity of our results. Additionally, data comparison was only between two years from 2019 and 2020, comprising a small data set. We acknowledge that data from 2019 may not represent historic incidence of domestic abuse and child abuse. Furthermore, only 28.3% of Bridgend schools wished to participate in the study. The views and themes collected from school questionnaires may therefore not be generalisable to all schools in Bridgend. Finally, the trends identified were specific to the Bridgend demographic and may, therefore, not reflect other parts of the UK.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, there was an increase in self-referrals and third-party referrals to local support services for domestic and child abuse concerns in Bridgend during the initial lockdown. In contrast, there was a decrease in referrals from the police for domestic abuse and a significant drop in child protection referrals from schools/ nurseries. This suggests reduced accessibility or engagement with public sector organisations during lockdown. Child protection and domestic abuse services need to consider alternative ways of working with this in mind.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105386.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Schools Questionnaire

References

- Aldridge J., Garius L., Spicer J., Harris M., Moore K., Eastwood N. Drugs in the time of COVID: The UK drug market response to lockdown restrictions, London. 2021. https://www.release.org.uk/sites/default/files/pdf/publications/Release%20COVID%20Survey%20Interim%20Findings%20final.pdf Release.

- Ashton K., Bellis M., Hughes K. Adverse childhood experiences and their association with health-harming behaviours and mental wellbeing in the Welsh adult population: A national cross-sectional survey. The Lancet. 2016;388:21. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee D., Rai M. Social isolation in Covid-19: The impact of loneliness. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2020;66(6):525–527. doi: 10.1177/0020764020922269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbara G., Facchin F., Micci L., Rendiniello M., Giulini P., Cattaneo C.…Kustermann A. Covid-19, lockdown, and intimate partner violence: Some data from an italian service and suggestions for future approaches. Journal of Women’s Health. 2020;29(10):1239–1242. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2020.8590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellis M.A., Ashton K., Hughes K., Ford K., Bishop J., Paranjothy S. Public Health Wales; 2015. Adverse childhood experiences and their impact on health-harming behaviours in the Welsh adult population. [Google Scholar]

- Berrios D.C., Grady D. Domestic violence. Risk factors and outcomes. The Western Journal of Medicine. 1991;155(2):133–135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhopal S., Buckland A., McCrone R., Villis A.I., Owens S. Who has been missed? Dramatic decrease in numbers of children seen for child protection assessments during the pandemic. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2021;106(2) doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury-Jones C., Isham L. The pandemic paradox: The consequences of COVID-19 on domestic violence. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2020;29(13–14):2047–2049. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S.M., Doom J.R., Lechuga-Peña S., Watamura S.E., Koppels T. Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2020;110(104699) doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron F., Plancq M.C., Tourneaux P., Gouron R., Klein C. Was child abuse underdetected during the COVID-19 lockdown? Archives de Pédiatrie. 2020;27(7):399–400. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2020.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartier M.J., Walker J.R., Naimark B. Separate and cumulative effects of adverse childhood experiences in predicting adult health and health care utilization. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2010;34(6):454–464. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoffersen M., Soothill K. The long-term consequences of parental alcohol abuse: A cohort study of children in Denmark. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;25(2):107–116. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleaver H., Unell I., Aldgate J. The Stationery Office; London: 2011. Children’s needs – Parenting capacity. Child abuse: Parental mental illness, learning disability, substance misuse, and domestic violence. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas M., Katikireddi S.V., Taulbut M., McKee M., McCartney G. Mitigating the wider health effects of covid-19 pandemic response. BMJ. 2020;369:1557. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson E.W., Craven C.L., Tisdall M.M., James G.A. The impact of social distancing on pediatric neurosurgical emergency referrals during the COVID-19 pandemic: A prospective observational cohort study. Child’s Nervous System. 2020;36(9):1821–1823. doi: 10.1007/s00381-020-04783-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garstang J., Debelle G., Anand I., Armstrong J., Botcher E., Chaplin H.…Taylor J. Effect of COVID-19 lockdown on child protection medical assessments: A retrospective observational study in Birmingham, UK. BMJ Open. 2020;10(9):1–6. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green P. Risks to children and young people during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020;369:1–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hills, et al. Global prevalence of past-year violence against children: A systematic review and minimum estimates. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3) doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HMRC Coronavirus job retention scheme statistics. 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/coronavirus-job-retention-scheme-statistics-january-2021/coronavirus-job-retention-scheme-statistics-january-2021#main-points

- Hughes K., Lowey H., Quigg Z., Bellis M.A. Relationships between adverse childhood experiences and adult mental well-being: Results from an English national household survey. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2906-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivandic R., Kirchmaier T., Lintons B. Centre for Economic Performance (CEP), London School of Economics and Political Science; 2020. Changing patterns of domestic abuse during Covid-19 lockdown; p. 1729. [Google Scholar]

- Jaudes P.K., et al. Association of drug abuse and child abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1995;19(9):1065–1075. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00068-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovler M.L., Ziegfeld S., Ryan L.M., Goldstein M.A., Gardner R., Garcia A.V., Nasr I.W. Increased proportion of physical child abuse injuries at a level I pediatric trauma center during the Covid-19 pandemic. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2021;116 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104756. [104756] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriacou D.N., Anglin D., Taliaferro E., Stone S., Tubb T., Linden J.A.…Kraus J.F. Risk factors for injury to women from domestic violence. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;342(25):1892–1898. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912163412505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson M., Piel M.H., Simon M. Child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic: Consequences of parental job loss on psychological and physical abuse towards children. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2020;110:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaker D. Office for National Statistics; 2021. Labour market overview, UK: January 2021 statistical bulletin.https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/uklabourmarket/january2021 January, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn R.M., Avis J.L., Lenton S., Amin-Chowdhury Z., Ladhani S.N. Delayed access to care and late presentations in children during the COVID-19 pandemic: A snapshot survey of 4075 paediatricians in the UK and Ireland. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2021;106(2):1–2. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M., Allen J., Goldblatt P., Herd E., Morrison J. The pandemic, socioeconomic and health inequalities in England. Institute of Health Equity; London: 2020. Build back fairer: The COVID-19 Marmot review. [Google Scholar]

- Masilamani K., Lo W.B., Basnet A., Powell J., Rodrigues D., Tremlett W., Jyothish D. Safeguarding in the COVID-19 pandemic: A UK tertiary children’s hospital. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2020;106 doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-320354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May-Chahal C., Cawson P. Measuring child maltreatment in the United Kingdom: A study of the prevalence of child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29(9):969–984. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay M.M. The link between domestic violence and child abuse: Assessment and treatment considerations. Child Welfare. 1994;73(1):29–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/riskprotectivefactors.html

- NSPCC The impact of the coronavirus pandemic on child welfare: Domestic abuse. 1–13. 2020. https://learning.nspcc.org.uk/research-resources/2020/coronavirus-insight-briefing-sexual-abuse

- NSPCC The impact of the coronavirus pandemic on child welfare: Physical abuse. 2020. https://learning.nspcc.org.uk/research-resources/2020/coronavirus-insight-briefing-physical-abuse

- ONS Child abuse in England and Wales: Statistical bulletin. [pdf] 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/bulletins/childabuseinenglandandwales/march2020 (Accessed 09.09.2021)

- ONS Domestic abuse in England and Wales: Overview [pdf] 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/bulletins/domesticabuseinenglandandwalesoverview/november2020 Accessed 09.09.2021.

- ONS Domestic abuse during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, England and Wales: November 2020 [pdf] 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/articles/domesticabuseduringthecoronaviruscovid19pandemicenglandandwales/november2020 Accessed 11.09.2021.

- Pollard M.S., Tucker J.S., Green H.D. Changes in adult alcohol use and consequences during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(9):2022942. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.22942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkumar R.P. COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2020;52:102066. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley G.S., Bailey J.W., Bright D., Davies A. Knowledge and awareness of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) in the public service workforce in Wales: A national survey. Public Health Wales NHS Trust. 2019 doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2906-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roesch E., Amin A., Gupta J., García-Moreno C. Violence against women during covid-19 pandemic restrictions. BMJ. 2020;369:2–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacco M.A., Caputo F., Ricci P., Sicilia F., De Aloe L., Bonetta C.F.…Aquila I. The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on domestic violence: The dark side of home isolation during quarantine. Medico-Legal Journal. 2020;88(2):71–73. doi: 10.1177/0025817220930553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seddighi H., et al. Child abuse in natural disasters and conflicts: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2019;22(1):176–185. doi: 10.1177/1524838019835973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidpra J., Abomeli D., Hameed B., Baker J., Mankad K. Rise in the incidence of abusive head trauma during the COVID-19 pandemic. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2020;0(0):2020. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . United Nations; Geneva: 1989. United Nations convention on the rights of the child.https://ecommons.cornell.edu/bitstream/handle/1813/98856/crc.pdf?sequence=1 Available at: [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Women 2020: Trends and statistics. 2020. https://worlds-women-2020-data-undesa.hub.arcgis.com/ URL: (Accessed 12.10.2021)

- Welsh Government Welsh index of multiple deprivation (full index update with ranks): 2019. 2019. https://gov.wales/welsh-index-multiple-deprivation-full-index-update-ranks-2019 URL.

- Women'’s Aid A perfect storm: The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on domestic abuse survivors and the services supporting them. Bristol: Women's Aid. [pdf] 2020. https://www.womensaid.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/A-Perfect-Storm-August-2020-1.pdf

- World Health Organization . 106(2) 2020. COVID-19 and violence against women: What the health sector/system can do. URL. (Accessed 12.10.2021) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Schools Questionnaire