Abstract

Background

Australia experienced a low prevalence of COVID-19 in 2020 compared to many other countries. However, maternity care has been impacted with hospital policy driven changes in practice. Little qualitative research has investigated maternity clinicians’ perception of the impact of COVID-19 in a high-migrant population.

Aim

To investigate maternity clinicians’ perceptions of patient experience, service delivery and personal experience in a high-migrant population.

Methods

We conducted semi-structured in-depth interviews with 14 maternity care clinicians in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. Interviews were conducted from November to December 2020. A reflexive thematic approach was used for data analysis.

Findings

A key theme in the data was ‘COVID-19 related travel restrictions result in loss of valued family support for migrant families’. However, partners were often ‘stepping-up’ into the role of missing overseas relatives. The main theme in clinical care was a shift in healthcare delivery away from optimising patient care to a focus on preservation and safety of health staff.

Discussion

Clinicians were of the view migrant women were deeply affected by the loss of traditional support. However, the benefit may be the potential for greater gender equity and bonding opportunities for partners.

Conflict with professional beneficence principles and values may result in bending rules when a disconnect exists between relaxed community health orders and restrictive hospital protocols during different phases of a pandemic.

Conclusion

This research adds to the literature that migrant women require individualised culturally safe care because of the ongoing impact of loss of support during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, Midwives, Pandemics, Maternity care, Migrants, Social support

Statement of significance

Problem or issue

Limited qualitative research exists on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the experience of clinicians providing maternity care to high-migrant populations.

What is already known

Health outcomes in migrant populations can be improved. Research indicates barriers to high-quality maternity care can be a result of rapid changes during the pandemic.

What this paper adds

Clinicians in maternity care are impacted by migrant populations ongoing loss of support. Culturally competent care should facilitate support and promote equitable heath care access.

Maternity care has shifted focus from women-centred to clinician safety. COVID-safe policies should be dynamic and reflect community risk to optimize staff pandemic policy compliance.

Introduction

‘It takes a village to raise a child’… but what happens when the village is locked out [1]. The magnitude and speed of the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact since the beginning of 2020 has been devastating, including sudden country border closures with Australian international borders closing on March 20, 2020 [2]. The impact of COVID-19 is largely due to direct associated morbidity and mortality as well as indirect economic, social and health care delivery disruptions [3,4]. Australia has been fortunate with the early containment of COVID-19 at the start of the pandemic in 2020. Significant loss of life has been avoided through a variety of public health measures including closing international borders, quarantining of overseas travellers, comprehensive contact tracing, and a population that was largely compliant to intermittent movement restrictions and ‘lockdown’ isolation measures when required [[5], [6], [7]].

The early containment and management gains of COVID-19 in Australia was tempered with a slow uptake and access to COVID-19 vaccination compared to other OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries in 2021, with media documenting the slow progress [8,9]. The Australian community has therefore experienced ongoing vulnerability to COVID-19 outbreaks. This vulnerability has been highlighted by sudden varied population lockdown orders due to state and nation-wide outbreaks of the highly contagious COVID-19 Delta strain in mid-2021. Rolling movement-restriction health orders occurred in 2021 primarily in the metropolitan areas of Sydney and Melbourne, with Sydney experiencing nearly four months of lockdown orders with easing of restrictions from mid-Oct 2021. During this time in 2021, COVID-19 cases occurred among women in Western Sydney who were pregnant and admitted to hospital. The prevalence of COVID-19 in New South Wales (NSW) was greatest in the high migrant population in Western Sydney [10].

The response to COVID-19 in maternity care across Australia has varied since the commencement of the pandemic. A survey of 620 Australian midwives conducted in May–June 2020 reported a varying response by hospitals in implementing restrictions of visitor and support persons due to COVID-19 [11]. These restrictions differed from no visitors or support persons permitted to no restrictions at all implemented. This is possibly a reflection of the varied assessment of risk in the different states and regions of Australia due to the different dynamics and risk profiles of particular outbreaks at various times throughout the pandemic. In the Bradfield et al. study, 16 midwives from across Australia were also interviewed about their experience of providing care during the pandemic. Among key findings, clinicians reported experiencing many challenges to providing women-centred care [11]. One of the main themes also identified in this study was ‘coping with rapid and radical change’, reflecting the situation that, despite a low prevalence of COVID-19 cases, providing maternity care has been problematic due to rapid, and sometimes contradictory, changes in policies.

A Spanish qualitative study of 14 midwives who had cared for COVID-19 positive women during pregnancy and childbirth, explored ‘challenges and differences when working in a pandemic’ [12]. They found staff were stressed and overwhelmed with constant changes in guidelines. These findings were consistent with the Australian experience of midwives reported by Bradfield et al., that midwives found it challenging to provide consistent supportive practice and that this was a barrier to women-centred care [13].

Although Australia has not experienced the death rate from COVID-19 that some countries have, significant stress, ongoing risk and impact exist for the community and clinicians. A study of health care workers (nurses, doctors, allied health and non-clinical) in Melbourne in mid-2020, found rates of psychological distress comparable to countries that experienced high prevalence of COVID-19 with 30% of health workers in Melbourne, Australia during the study screening positive for work-place burnout [14].

The health order restrictions on movement and border closures during the COVID-19 crisis has changed access to family and friends for many women potentially impacting their childbirth experience [15,16]. Women who utilise the maternity services in Western Sydney Local Health District (WSLHD) are predominantly born in a non-English speaking country (58%) [17], with relatives living in countries that are significantly impacted by COVID-19. A previous study at Westmead Hospital found 85% of South Asian or Chinese women planned to have relatives visit from overseas to provide support during pregnancy and the postnatal period [18]. In person support from overseas relatives is no longer available due to government mandated international flight restrictions in Australia. How clinicians have perceived the effect of COVID-19 on social support networks for overseas born and Australian born women and the impact on care in the peripartum period to our knowledge has not been investigated.

Improved understanding of clinicians’ experience and difficulties caring for women and their families during the COVID-19 pandemic can assist with enhanced maternity care for families and professional support. This understanding may improve future pandemic planning to deliver care in diverse multiethnic communities. The aim of this study was to explore the experience of maternity clinicians serving a high migrant population during the COVID-19 pandemic, including investigating perceptions of patient experience, service delivery and personal experience of living in the pandemic.

Methods

Design

A qualitative study design with data generated from semi-structured individual interviews was employed for this study. Reflexive thematic approach was used as described by Braun and Clarke [19]. This approach was chosen as it provided the flexibility of inquiry required to examine the novel lived experiences of clinicians serving a culturally diverse patient population in an evolving pandemic where no previous data was available.

Setting

Midwives and medical staff were recruited at a major tertiary referral hospital in Western Sydney Local Health District (WSLHD), NSW, Sydney, Australia. Sydney is the largest city in Australia with a population of 5.4 million. WSLHD has the highest overseas migration gain for the state of NSW [20]. The study hospital is the tertiary referral hospital for the Local Health District population of more than 946,000 residents [21]. This hospital has an average of 5500 births per year. The study hospital is within a health district that has 58% of the mothers born in a non-English speaking country and the highest South Asian maternal population (25%) in the state of NSW [17].

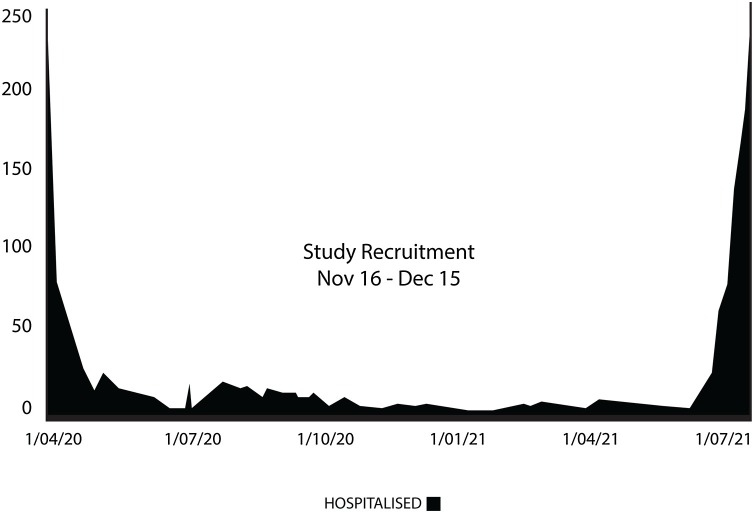

Recruitment and interviews occurred during a period of no locally acquired COVID-19 cases in the state of NSW, after the first high prevalence COVID-19 case period in March-April 2020 (Fig.1 ). During this first surge there had been no COVID-19 positive pregnant women admitted at the study hospital. Approval for COVID-19 vaccines did not occur in Australia until 2021 and were not available to health staff or the community during the study period.

Fig. 1.

COVID-19 hospitalisation in New South Wales, Australia April 2020–July 2021.

Recruitment period for COVID-19 maternity clinician qualitative study: November–December 2020.

(Graphic T Melov based on Source https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-03-17/coronavirus-cases-data-reveals-how-covid-19-spreads-in-australia/12060704#hospitalisation).

Participants

Inclusion criteria for the study required participants to be a registered midwife or medical practitioner who had been employed at the study hospital for greater than 12 months in the Department of Women’s and Newborn Health. This inclusion criteria was to ensure participants could discuss their experience since the beginning of the pandemic. Participants were recruited through information posters in maternity care staff areas and routine work maternity staff email pathways. Purposive sampling was utilised to enrich data collection for varied clinical experience of participants from all maternity care areas [22]. Recruitment and interviews occurred over a four-week period from 18th November 2020 to 16th December 2020.

Thirteen clinicians were interviewed face to face and one by a secure video link. All but one of the participants were women and most of the clinicians were midwives, with two participants medical doctors. Approximately 40% of the clinicians in the study were migrants themselves reflecting the local migrant population. Eight of the participants stated they were parents, all with children living at home except one who had adult children not living at home. Further demographic information is presented in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Characteristics grouped by years of experience of 14 maternity clinician participants during the COVID-19 pandemic in a tertiary referral hospital Sydney, Australia.

| Years of experience | Age group represented | Primary maternity clinical area (n) |

|---|---|---|

| 1−5 | <30 | Continuity of Care (1) |

| Antenatal Clinic (1) | ||

| Mixed Areas (2) | ||

| 6−9 | 30−40 | Continuity of Care (1) |

| Postnatal Ward (1) | ||

| 10−20 | >40 | Birth Unit (1) |

| 30−40 | Mixed Areas (2) | |

| >20 | >40 | Antenatal Clinic (3) |

| Postnatal Home Care (1) | ||

| Continuity of Care (1) |

Interviews conducted over four weeks: November-December 2020.

Registered midwives: 11, Student midwife: 1, Trainee obstetrician: 1, Obstetrician: 1.

Data collection

A semi-structured interview schedule was used to collect data consisting of three categories for exploration of the participants understanding of: (1) clinicians’ perceptions of patient experience (including support required), (2) service delivery and (3) personal experience of living in the pandemic. The leading question for each category investigated were: ‘Can you tell me what your perceptions of changes in women’s family support has been like during COVID pandemic?’ In exploring service delivery: ‘Can you tell me about your experience caring for pregnant women during the COVID pandemic?’ And for the final category of personal experience the lead question was: ‘How have you felt in yourself during the COVID pandemic?’ Questions regarding family support are defined in this study to mean a person’s partner, relatives, and people around who can be called on to provide emotional, tangible (instrumental), and informational support.

All interviews were conducted by a single investigator who is an experienced midwife and researcher (SM). The interview progress, transcript coding and analysis were overseen by an expert qualitative researcher (JM). The interviews ranged from 28 to 65 min, with eight interviews over 50 min, and one interrupted at 15 min and unable to be continued. Recruitment ceased at saturation when sufficient rich data from a diverse range of participants was collected to generate insights and meaning for the research question. This was in the context of the recruitment period occurring in a COVID-19 ‘lull’ with loosened restrictions and a stable government COVID-19 response. A total of 665 min of interviews with clinicians were recorded and subsequently transcribed.

A professional transcription service provided verbatim text of audio recording. SM reviewed transcriptions against audio for accuracy. To ensure confidentiality of participants all transcriptions were de-identified.

Data analysis

Reflexive thematic data analysis was used within a framework of the three primary areas of clinician perceptions of patient experience, service delivery and personal experience of living in the pandemic.

Analysis was based on the six phases as set out by Braun and Clarke [23]; these were not sequential but commenced with deep familiarisation with the data. This first step of familiarisation was enhanced by the first author completing all interviews, therefore aware of greater context below surface transcription detail. Field notes were also used to assist with the familiarisation process. The other five phases for analysis were generating codes, exploring initial themes, reviewing initial themes, finalising and naming themes and then producing the report [19].

After familiarisation with data, codes were defined by the two primary authors JM and SJM utilizing both sematic and latent meaning to provide richer understanding and categorisation of participant data by JM and SM. Assumptions and context of code generation were checked through non-discipline social scientist ‘outside’ voice of senior author (JM) in the analysis process.

Generating final themes were based on central connecting concepts. The five phases of analysis were conducted by authors SM and JM with all authors reviewing and reaching consensus on final themes. Consensus was reached iteratively for final themes and final report. NVivo was used for data management and analysis (QRS International Pty Ltd 2020).

Investigators addressed reflexivity particularly in consideration of the primary researcher’s own position as embedded within both the subject matter and shared participant professional experience as a clinical midwife. A further reflexive consideration was that all investigators were experiencing the pandemic and it is acknowledged this shared experience enhanced insight into the areas under investigation in this study.

The collection, analysis and presentation of in-depth, detailed and contextualised data, paying critical attention to matters of reflexivity from the perspectives of authors SM and JM – in the interview process but also in the rationale and implementation of all phases of the study – enhanced rigour, trustworthiness and quality. Quality of data coding and analysis was further strengthened by author JM evaluating, cross checking, and, where necessary, reassessing both coding frames and coded text in iterative dialogue with author SM.

Ethical considerations

The interviewer is employed in the same institution however has no managerial role and no working relationship with any participant. All participants were provided with written information and signed a consent form that is stored by the interviewing researcher in a locked research room. Audio data was securely deleted after transcription verification. All transcriptions and data were de-identified for analysis and investigator discussions to ensure anonymity of the participants from researchers who may be colleagues. All research data is securely stored with password protection and access only by named investigators. The final manuscript was reviewed for identifiers by an independent study-site midwifery researcher. Approval was granted by Western Sydney Local Health District Human Ethics Committee (2020/ETH02074) 23 September 2020.

Findings

The three main themes within the areas explored were: COVID-19 related travel restrictions result in loss of valued family support for migrant families; For the greater good, loss of efficient women-centred care; Challenges and difficulties in difficult times- you just dealt with it. The main themes and subthemes are provided in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Main themes and sub-themes. Exploring the COVID-19 pandemic experience of maternity clinicians in a high migrant population and low COVID-19 prevalence country: a qualitative study.

| 1. | Clinicians’ perceptions of patient experience |

|---|---|

| Main theme | |

| COVID-19 related travel restrictions result in loss of valued family support for migrant families | |

| Sub-themes | |

| Birth and cultural differences: “…they’re just by themselves, as opposed to an Aussie couple…” | |

| The cultural practice of postpartum extended in-house support from overseas | |

| Loss of support and impact on clinical care | |

| Changing support from partners: “…the fathers themselves actually did step up” | |

| Mental health impact of loss of support: “Big time struggling because she’s sort of just very isolated” | |

| Missing out on important life events in the pregnancy journey “…husbands are missing the births of their babies” | |

| The hospital is not a safe place to be “… we’re a big tertiary hospital, and we’re the COVID central” |

| 2. | Maternity care service delivery during COVID-19 |

|---|---|

| Main theme | |

| For the greater good, loss of efficient women-centred care: “it was just a matter of plugging the holes when you could identify them” | |

| Sub-theme | |

| Doing your own thing: “This doesn’t feel right …” |

| 3. | Clinicians’ personal experience during COVID-19 |

|---|---|

| Main theme | |

| Challenges and difficulties in difficult times- “you just dealt with it”;“… and we came straight off the bushfires” | |

| Sub-themes | |

| Guilt- “can I keep everyone safe?”; “…that was the fear. Taking it home and then … them not surviving it.” | |

| Self-care: new activities and work facilitating connection with people |

Clinicians’ perceptions of patient experience

COVID-19 related travel restrictions result in loss of valued family support for migrant families

In this culturally diverse migrant population, the main theme woven through all aspects of this area of inquiry ‘Perception of patient experience’ were related to the impact travel restrictions had on family support, which in turn impacted both patients and clinical care. All clinicians described the lack of family support from overseas as one of the biggest challenges they perceived for women during the COVID-19 pandemic at the study hospital. A typical response was:

…the most important thing is the inability to have extended family, potentially, travel to be with them to give support around the time of the delivery, and with the newborn baby… that choice has been taken away from them. (Clinician 11 Obstetrician).

Birth and cultural differences: “…they’re just by themselves, as opposed to an Aussie couple…”

Four clinicians identified that there was a difference that separation from traditional family support had on overseas born women when compared to Australian born women. One clinician observed that women from India were highly reliant on relatives, and they had a strong family connection. This midwife explained she found the connection to family was different to Australian born women who often wanted to experience the pregnancy journey with just their partner.

…the women seem to be very sad and depressed and lonely because their mother and their mother-in-law can’t come from India to support them… I think they feel as though they’re being abandoned because of the virus, that they’re just by themselves, as opposed to an Aussie couple that feel as though they want to cope by themselves. (Clinician 1 Antenatal Clinic Midwife)

This midwife, with over 20 years’ experience, went on to explain how she found that there was not a reliance or even usually a mention of relatives for Australian born women: “They talk about the couple and themselves, whereas [Indian women] tend to incorporate the whole family into this childbearing support mechanism.” Other clinicians also mentioned the individualistic nature of pregnancy for some Australian born families. A young trainee obstetrician observed; “Caucasian families seem to just really want their partner and no one else” (Clinician 10). Two midwives stated that some of the Australian born nuclear family units found COVID lockdown beneficial to isolate themselves from the available but uninvited extended family and visitors, COVID-19 restrictions provided protected time.

…for some [Australian born women], they didn’t mind it, actually, because that meant less family coming over. And so they could enjoy that time just with their partner and with their baby, … They were like, “Yeah, I prefer it. I can just stay at home, and now I can use COVID as an excuse for them not to come. (Clinician 8 Continuity of Care Midwife)

They really liked being isolated and living in their bubble. And I found that for couples, in particular, the dad and the mum and the baby were just this tiny little world …No, the Australian, particularly the Australians have loved it. (Clinician 4 Postnatal Home Care)

Some clinicians stated this contrasted with the deeply felt sense of loss of support from extended family that overseas born women frequently discussed.

The cultural practice of postpartum extended in-house support from overseas

The loss of support for many overseas born women is within the context of a cultural norm. Most clinicians described the importance and common practice among South Asian and Chinese migrant women of in-home family support coming from overseas during pregnancy and for many months postpartum.

…it’s nearly always the mum, or the mother-in-law, are always there, especially for the first three months, to help out, to cook, to help to clean. And that’s just their normal way of life. And if they were back home in their country that’s how it would be. They would have even more family, and that’s just their way of life. So to be here in a foreign country, and to not have that community that you usually have that’s normal to their culture, would definitely … really depress them. (Clinician 8 Continuity of Care Midwife)

Clinicians described the very practical and tangible nature of support during the postpartum that some cultural groups of women knew they were missing. One clinician stated that relatives:

…do everything for these mums; they will cook, clean, they take care of their baby, they do the night shift if mum needs a sleep. Mum really doesn’t need to do anything except have the baby handed to her to breastfeed basically. (Clinician 4 Postnatal Midwife)

The support traditionally provided and now absent from overseas relatives, can be extended and substantial;

“they stay for about six months, sometimes longer and then they swop over depending on each side of the family. So, there’s a good year or a couple of years that they have support in the home where they’re not having that now”. (Clinician 10 Trainee Obstetrician)

Loss of support and impact on clinical care

More than half the clinicians described the impact on clinical care from loss of support from overseas relations as increased time commitment for two primary reasons: providing greater parenting education and increased time required in the clinical encounter to address psychosocial needs. Clinicians stated both new mothers and multiparous women may require extensive help as some multiparous women had previously had live-in assistance from relatives with all baby care needs and therefore required more education support. This lack of support was exacerbated as clinicians felt many women did not attend antenatal classes or were unable to attend due to COVID-19 antenatal education class disruption. As one midwife described it:

The primips [primiparous women] in particular with their mother crafting and breastfeeding, they needed more intensive support. Multips [multiparous women] who weren’t used to it also needed reminding. Do you remember what it was like before? And they had to stop and think how much their mum did for them, or their mother-in-law. (Clinician 4 Postnatal Midwife)

The increased time required for patient care by clinicians was also due to greater demand for emotional support for women. Another midwife described a woman from Europe who had a history of postpartum depression and had organised for her relatives to fly-in to provide support, which, because of international flight restrictions, did not happen.

… she couldn’t get her sister or her mum, or anybody from overseas, really made things worse… you have to take on that added responsibility of being that friend and that family and the clinician at the same time. And that woman was very draining. (Clinician 8 Continuity of Care Midwife)

Changing support from partners: “…the fathers themselves actually did step up”

Nearly all clinicians discussed the changing role of husbands to provide support that would have been provided by overseas relatives. Research has found that during the pandemic partners have felt they were missing out on aspects of the pregnancy journey [24]. However, in our findings clinicians stated some cultural groups may have benefited from more opportunities to be with their partner in protected time to provide support that may have been provided by female relatives traditionally. As one clinician explained:

And a lot of the women said that’s the expectation in Australia that the husband and the wife or both parents are involved in looking after the baby. Not just the mum and the grandmother or the dad getting a few cuddles at the end of the day. And the husbands were actually pretty happy to be allowed to do that because I think culturally, they are pushed out. They’re pushed out by the older women… I think a lot of them actually felt really great that the older women weren’t around bossing them around and the couple could actually work it out for themselves. (Clinician 5 Continuity of Care)

More than half the clinicians discussed in some way how the COVID-19 experience had impacted and challenged traditional male provider role, particularly regarding gender roles and equity, this was perceived as more apparent within migrant couple’s experience. The role of male partners engaged with parenting, inclusive of division of household tasks were highlighted as external support network was absent due to restrictions placed by COVID-19 on overseas relatives: “the fathers are doing a lot of it now, and I’ll tell you what, they’re doing a great job” (Clinician 4 Postnatal Home Care).

Mental health impact of loss of support: “Big time struggling because she’s sort of just very isolated”

Almost all clinicians stated they felt COVID-19 had increased migrant women’s feeling of isolation. Ten clinicians discussed that the pandemic had increased mental health concerns for all women. Most of the clinician who discussed mental health, specified that they felt that there was an increase in anxiety among women both antenatally and postnatally. This was often attributed to loss of support from relatives unable to travel to stay with migrant women. Some clinician reported cases they recalled of women not coping:

…she has no friends, her family are all in the UK, they were going to come support her for the birth, but now they’re not. So she’s really massively struggling. She’s having anxiety attacks. Big time struggling because she’s sort of just very isolated. (Clinician 7 Birth Unit Midwife)

Clinician 8 who works within the continuity of care model stated loss of support: “It’s definitely increased levels of anxiety”. This clinician also reported that the fear of COVID-19 also impacted mental health “there was a lot of questions about how it could affect my baby, how it could affect me, and that increased levels of anxiety for all women”. Another experienced midwife (Clinician 5), who was able to observe women and their families at home throughout their pregnancy journey with continuity of care said: “…some of the women felt sad that their babies were born at this time. They felt that they weren’t able to be joyous and weren’t able to really celebrate the birth of their children with their family.”

Missing out on important life events in the pregnancy journey “…husbands are missing the births of their babies”

Almost all clinicians identified that partners and other important support people for women were missing significant life experiences in the pregnancy journey. Clinicians stated this was felt differently by some cultural groups in the birth unit. As one trainee obstetrician observed; “Pacific Islander patients, they often have a lot of family members in birth – like, all the women. So not having that might have been hard for them” (Clinician 10 Trainee Obstetrician).

The rules to provide a COVID-19 safe environment within the hospital appeared to some staff to not be consistent with the flexibility of social distancing rules that NSW state public health orders were allowing for the general population at the time of the study.

It’s pretty brutal, really. I think even now they’re still only allowed one [support person]. But you can have a whole football stadium full of people, but you can only have one person. So a lot of them are choosing not to have their partners at the birth. (Clinician 7 Birth Unit)

This clinician continued that they felt the support person rules were not equitably applied within the hospital: “…if you contacted the [hospital] and gave a reason of some kind, then basically you were approved for two … and it’s only the ones that kick up a song and dance that have been allowed to have more than one [support person].” This raises the issue of equity of access for non-English speaking women who find it more difficult to negotiate the healthcare system and actors within it [[25], [26], [27]].

The hospital is not a safe place to be “… we’re a big tertiary hospital, and we’re the COVID central”

Seven of the clinicians discussed that woman felt that the hospital environment may be unsafe, a risk for COVID-19 exposure… “I think they just didn’t want to risk coming in; either would not ring up or would cancel” (Clinician 3 Antenatal Clinic). Substantial evidence exists that there are barriers for migrant populations to access health care, COVID-19 places another barrier for women during this period [26,27]. Particularly in the first wave of the pandemic when there was more uncertainty, a Continuity Care Midwife (Clinician 5) said; “I think they were just really scared, really, really scared, and just didn’t really want to come [to hospital]”.

Maternity care service delivery during COVID-19

For the greater good, loss of efficient women-centred care: “it was just a matter of plugging the holes when you could identify them”

All clinicians discussed issues that were essentially rooted in the aim of a health care system attempting to rapidly reorganise to protect the greatest number of staff and patients from the looming threat of COVID-19 infection; ‘For the greater good’. Providing optimal care was balanced with providing COVID-19 safe care. Some staff expressed concern that their safety was not prioritised and others that too much concern was given to staff safety and consequently patient care was reduced. Nine clinicians identified unclear and constant changes in practice guidelines as impeding care and creating uncertainty for both clinicians and the families in their care. As one clinician put it:

…the rules about one person in the birth unit only, no swapping. And then at one point it became OK, you could swap, but only once. I think now you can swap more than that. I’m not really sure, really... “Maybe ring birth unit when you’re closer to term, and I’ll ask them.” Which, you know, then when you’re in birth unit and the phone never stops ringing, you sort of think, “Oh, maybe I shouldn’t have said that”. (Clinician 10 Trainee Obstetrician)

Some clinicians thought mixed messages to staff resulted as hospital administration assessed changing COVID-19 risks, based on evolving overseas experiences and also the process of interrogating existing clinical practices. “Well, we had five different rules in five days [laughter]. So, it was just a very drastic change, just a different rule every day that was being brought in with all the emails and things’ (Clinician 9 Antenatal Clinic). However, other clinicians expressed how well they thought the service had responded:

I think there was a lot of people really making an effort to work out the best thing to do. I think it was excellent how quickly they shut down the hospital. I think that made a massive difference to our service capability. I think if we’d left the hospital open for six weeks it would have been pandemonium. (Clinician 5 Continuity of Care)

Doing your own thing: “This doesn’t feel right ...”

Most clinicians in our study have found the shift in clinical care from the centrality of a ‘woman-centred’ approach to the ‘greater good’ of safety for both patients and a new higher focus on staff safety, to be problematic. Maternity staff in this study stated they were often making their own judgment about risk and clinical care. A sub-text of ‘doing your own thing’ expresses the underlying concept of comments by most clinicians to provide optimal care that adjusted to the new rules but also conformed to their individual ethical maternity care standards. This was particularly in the context of low or zero COVID-19 local community prevalence.

…they encouraged phone consults. And I tried one. I did do one, but it just didn’t feel right. And then also with the women as well. They’ll be like “Oh, so you’re not going to see me?” And that just – yeah, it was … It was like a wounded soul. They’re so hurt by it. They understand but they’re hurt, and I’m like – and then I was like, nah, just … This doesn’t feel right. (Clinician 8 Continuity of Care)

Clinicians expressed frustration at following recommendations to reduce exposure risk to COVID-19 to themselves at the expense of providing optimal care. This was discussed by most clinicians regarding the time limitation rule for consultations with women and the perceived impact this had on clinical care. Clinicians found following the short visit rule, of staying with a patient for only 15 min to reduce COVID-19 contact risk and maintain social distancing, unsatisfactory. As one clinician said: “you’d find that they had other questions, so we were constantly going over time… it was really difficult, and I could never sort of say to them, uh, 15 minutes is up, I'm leaving” (Clinician 5 Continuity of Care). Another clinician elaborated:

You know, say you’re talking to a diabetic mother about expressing, and wanting to give her the syringes and the info sheet. If you really stuck to the 15, well, you just wouldn’t be able to do that. You’d just get through her diabetic care, check her scan, and send her on her way. But that was really suboptimal. (Clinician 10 Trainee Obstetrician)

Clinicians’ personal experience of living through the pandemic

Challenges and difficulties in difficult times- “you just dealt with it”;“… and we came straight off the bushfires”

When clinicians discussed their personal experiences of living with the pandemic a central theme was; ‘Challenges and difficulties in difficult times- you just dealt with it’. All clinicians expressed that they had experienced adversity personally during the COVID pandemic. Some adversity was psychological with increased stress and anxiety. “I was on hyperalert, but I didn’t recognise it at the time … you just dealt with it” (Clinician 4 Postnatal Home Care). Three clinicians who had partners that were either healthcare workers or essential workers stated this situation increased the complexity of issues to deal with, including concerns with risk and safety. This is also within the context of the state of NSW experiencing the worst bushfire season on record with 4.9 million hectares of the state burned over the summer period [28].

It’s been tough because my husband’s …on the front line as well and we came straight off the bushfires. So he was off attending to those and not at home all the time with that and then we went straight into COVID. …challenging for our kids in that with both their parents being on the frontline. (Clinician 14 Postnatal Ward)

One in nine adults in Australia are informal carers and these are most likely to be women and often disproportionately take on extra duties of unpaid care [29]. Of the predominantly female group of fourteen clinicians interviewed, five clinicians described COVID-19 as a barrier to providing support to elderly parents. Some of these difficulties are shared by the general public, however, clinicians felt they were more at risk of infecting vulnerable or elderly relatives with COVID-19 “Am I transmitting the virus because I’ve interacted with so many people during the day?” (Clinician 1 Antenatal Clinic). One clinician who worked in the busy birth unit discussed this in relation to their particularly vulnerable parent: “My dad was unwell with cancer and having treatment, so we couldn’t go and see him” (Clinician 7 Birth Unit).

Clinicians from migrant backgrounds had similar stressful experiences to the migrant patient population with forced separation from extended family and restricted international flights. A Continuity of Care Midwife (Clinician 12) experienced the death of their mother during the pandemic who lived overseas: “…in February, when my mum passed away, I was able to go back to my home country to sort out things”. She discussed the difficultly as an only child of managing remotely the complexity of caring for their elderly father, with significant health issues, who was left alone after the death of his wife.

…so I hire a 24-hour nanny as well. …he has to have 24-hour care. So I just worried about COVID-19, when it’s going to stop, because I have to go overseas next year to kind of sort things. So, I’m not sure at this stage. …the relatives visit him quite regularly. … no way to go, so yeah…I have like a webcam, like a kind of camera. I can just talk to them. (Clinician 12 Continuity of Care)

The difficulties of negotiating international travel and organising ongoing remote care of the clinician’s father highlights the complexities that a migrant workforce live with, maintaining connection to family in their country of origin. In our patient population these issues are focused on family and birth. However, in our workforce the issues also include illness and death, as the clinician continued “That’s the thing. I haven't buried my mum’s ashes yet, so I am hoping next year I can go” (Clinician 12).

Guilt- “can I keep everyone safe?”; “…that was the fear. Taking it home and then … them not surviving it.”

‘Guilt’ was another theme for clinicians living in the pandemic. Feelings of guilt were explicitly expressed by five clinicians. Some of the guilt was based in the personal ethical dilemma of balancing professional beneficence and personal risk to family. Anxiety surrounding the fear of COVID-19 transmission to vulnerable pregnant women or to clinicians’ families was expressed by nearly all clinicians. They also talked about stress around potentially not working if a long quarantine was required or when waiting for COVID-19 swab results. As one clinician put it, “You feel like why do I feel guilty. You think- I could be working, I’m really actually OK. But you can’t come in” (Clinician 7 Continuity of Care). Some of the guilt was driven by knowing that there could be extra stress and workload for colleagues in this situation “… there’s always that burden that you’re … because in nursing you’re never replaced, so when you don’t come to work everybody else has to carry your load. So, you’re already feeling guilty” (Clinician 4 Postnatal Home Care). This altruistic concern to keep yourself safe for preservation of the maternity service was expressed by both midwives and medical staff as an obstetrician explained “anxiety around, especially, the vulnerability of yourself. So, if I was to get coronavirus or have to have a test, then it would mean me needing to be absent from work and unavailable for a period of time” (Clinician 11 Obstetrician). Another clinician elaborated the fear and anxiety associated with coming into contact with a potentially COVID-19 positive patient:

…the anxiety that I felt was sickening because I thought, uh, my goodness what have I done yesterday. So that was the Tuesday, and she rang me on the Tuesday night, so I was already home. So, I’d seen her. I’d seen other women. I’d seen my team members. I’d been at the hospital. I’d been home. I’d been with both of my children, who worked, and my husband who’s working from home, and I was panic stricken with the number of potential contacts that I could have hit. (Clinician 5 Continuity of Care)

There were five participants who had school age children, most discussed the importance of keeping their children safe. When discussing the greatest personal concern during the pandemic one clinician described the fear for the survival of her vulnerable children.

I think my kids getting it. Because they were high risk and maybe they wouldn’t survive it. I’m pretty healthy. I think if I – hopefully I would survive it. But maybe my kids wouldn’t. So I guess that was the fear. Taking it home and then … Them not surviving it... everyone else is at home and isolating, and you have to come to work and potentially look after these women. And then take that home to your kids. That was scary. (Clinician 7 Birth Unit)

For most clinicians attempting to ‘keep everyone safe’ to reduce risk manifested in what could be described as ‘coming home rituals’. As a clinician explained:

…we allocated this toilet, and my kids put [a sign] there, ‘the Corona room’ [laughs], ‘don’t enter’ They didn't go in that. We told them, we said OK, because we are both parents working in the hospital. OK, now with during this pandemic, we just need to try to protect you, what we can do. So that’s why. So we say OK, mummy and daddy were just changing our uniform in that room, and we will shower, everything in that room. (Clinician 6 Mixed Areas)

Clinicians discussed keeping safe mentally as part of what could be termed COVID safe rituals: As one clinician put it, “I feel OK, because I have enough toilet paper.”

Self-care: new activities and work facilitating connection with people

Clinicians also described self-care as part of the rituals of keeping safe mentally. New activities that clinicians said they purposefully engaged in for mental health included cooking, online shopping, doing puzzles, sketching and investigating the family tree. Exercise was also described as important. One clinician said she had started jogging and another two had bought bicycles during the pandemic.

Clinicians also described the importance and meaning for them to continue to work for their mental health during the pandemic. As one clinician said: “…being able to still birth with women and have that contact with them was a saving grace” (Clinician 5 Continuity of Care). Most clinicians felt a sense of purpose providing care for women in difficult times. Work was viewed both as anchoring a sense of self and helpful for self-care.

[At the beginning of the pandemic] I felt as though we were like crusaders coming to work. We were kind of like on the battlefields, that we deserved bravery medals to come because of this unknown. … were we all going to die? … when you come to work you think what's going to happen kind of thing. So I felt a sense of purpose and – I don't know what the word is, but you felt like a soldier in the battle kind of thing. For the greater good, here we are. We’re all going to die but it doesn't matter; here we are. (Clinician 1 Antenatal Clinic)

Discussion

It is estimated worldwide there is over 272 million migrants and in Australia approximately 50% of its population is either a migrant or a child of a migrant [30,31]. Migrant families have unique and more complex needs during pregnancy and birth than non-migrants, these include higher rates of stillbirth, preeclampsia and depression [32,33]. It is important particularly in Australia, to understand in depth the impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had in this population to optimise care and understand service provision. Our qualitative study aimed to explore the effect of the current pandemic among clinicians providing maternity care in a high migrant population. We identified three main themes in the data collected from maternity clinicians: ‘COVID-19 related travel restrictions result in loss of valued family support for migrant families’, ‘For the greater good, loss of efficient women-centred care’ and personal ‘Challenges and difficulties in difficult times- you just dealt with it’. This study adds to the limited maternity literature of the impact COVID-19 has had in high-migrant populations.

To our knowledge this is the first in-depth qualitative investigation that has specifically explored maternity clinicians’ perceptions of changes to family support including overseas relatives. We have identified loss of the overseas family support as a major and ongoing concern for migrant women during the pandemic which in turn can impact service delivery. It is of interest to note there is supporting evidence for this finding in the Bradfield et al. study as midwife participants mentioned the difficulty in providing women-centred care in a culturally safe way. This was to both women from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds and to Aboriginal women due to unmet cultural expectations [11].

High quality and supportive social relationships have been increasingly linked to resilience, well-being, and reduced morbidity and mortality [[34], [35], [36], [37]]. High quality social support can be defined to include optimally a combination of structural factors such as strong social networks and living arrangements or functional self-reported measures of support including an internal perception of high-availability of support [36]. Robust social support can be drawn on in times of adversity and can act as an emotional buffer. Access to strong networks of social support have been found to not only impact an individual’s health but also influence emotional connection and warmth of a mother and child relationship, with some research finding increased social support lays a foundation for improved parent child connection [38]. Understanding the disruption to this important aspect during pregnancy, birth and early childhood can be viewed as understanding an aspect of healthcare that has immediate impact and implications for both mental and physical health outcomes long-term. Our study has provided clear evidence of the impact of lack of support from overseas relatives has had for pregnant migrant women on the resulting effects for the provision of healthcare by a culturally diverse workforce providing maternity care to this population.

The COVID-19 pandemic is an acutely stressful event that has significant and detrimental impacts across the entire Australian population, particularly due to the uncertainly and swiftly changing capacity for individuals to connect with their usual support networks. In the specific context of perinatal care, networks that would usually provide a buffer against acute stress around significant events such as childbirth were largely absent. In particular, our participants stated that the impact on clinical care of the loss of the expected support network for migrant women included increased time required with women to provide adequate education and increased need for psychosocial support.

However, adding nuance to this finding, clinicians in our study also felt that Australian born women discussed the loss of relative support less or indeed stated they benefited from a family unit ‘bubble’ without having to interact with intrusive relatives during lockdown periods. These varied perspectives highlight the need for clinicians to refrain from assumptions about patient preferences and the need to individualise care and utilise cultural competency skills to provide optimal care.

The negative impact of mandated restrictions on support people during antenatal care and birth during COVID-19 pandemic is described in our study: as missing out on important life events in the pregnancy journey. This issue has been documented in social media and other supporting research [13,24,39].

Australian research has identified that partners felt psychological distress primarily concerning COVID-19 hospital restrictions [24]. However, clinicians in our study also described the adaptation and positive aspects for partners to the loss of support from overseas relatives. Clinicians felt husbands and partners were ‘stepping-up’ and filling the support-gap left by overseas relatives. The perceived benefit was that partners were more involved with newborn care, whereas previously they may have not had as much opportunity due to the cultural traditions of mothers and mother-laws inhabiting this space. Concepts about gender equity, or the lack of it, in the country of origin and within the migrant population is important to understand for service provision and the subsequent impact on women’s health. The risk of negative physical and mental health outcomes is associated with gender inequality, often because of reduced decision making within an intimate partner relationship [40,41]. The changing male role due to the impacts of COVID-19 within some migrant families may result in more equal gender relations that may in turn benefit partner’s relationship to infants, and also provide health benefits to women. The clinicians in our study were of the view there was some evidence of this changing male role in the migrant populations they served.

The imperative to preserve the healthcare workforce has become paramount during the pandemic. Large groups of health workers in isolation or unwell will result in reduced or possibly even no capacity to provide care. Our research found clinicians understood that institutional and government shift to a system-level ‘for greater good’ focus, led to women-centred care being swept away in a confusing array of changing protocols, and policy changes. An underpinning pregnancy care philosophy and policy for many years has been to provide a holistic ‘woman-centred’ maternity care service, although this ideal is often not well understood or achieved [42]. Providing optimal maternity care is thought to focus on a woman’s right to have choice of care, to be involved in decisions and have care that respects her emotional as well as physical needs [43]. A ‘woman-centred’ care framework has more recently been embedded in Midwifery National professional standards and the Australian pregnancy care strategic guidelines [44,45]. Although the precise definition and focus of ‘woman-centred’ care has been debated, the ideas remain central to particularly midwifery practice [42,46,47].

Evidence from our study suggests that the pandemic and associated protocol and policy changes has undermined attempts to embed ‘woman-centred’ care in contemporary clinical care, protocols and practice. COVID-19 precautions, for a variety of clinical and public health reasons, have shifted focus to a central tenant of protection of staff. Our findings of the loss of individual women-centred care are supported by other research [11]. There may be no ideal solution to this issue during high COVID-19 case prevalence and high risk to staff as preservation of service is vital. However, there is evidence that healthcare workers during COVID-19 are at greater risk of mental health challenges when exposed to practices that may be considered against a moral code [48], as one midwife in our study said: “This doesn’t feel right”. This information may inform appropriate mental health support to be offered to staff who are more acutely aware of morally and/or professionally dissonant practices.

We found the discordance occurred when staff felt a disconnect between reduced community restrictions due to low or zero case prevalence and onerous hospital restriction policies. Beneficence is an overarching principle in healthcare, a duty to act for the benefit of others [49]. Assessing risk for midwifery and medical obstetric staff is embedded in usual practice. In an environment where protocols are constantly shifting, we found staff were more likely to be utilizing this professional risk assessment skill-set during the pandemic and balancing beneficence and risk by, as clinicians put it, “doing your own thing”.

Although staff said they “just dealt with it” the challenges and difficulties the pandemic has thrown up to health worker’s personal lives have been significant. Providing care in a high-migrant population may also mean this migrant diversity is reflected in the workforce. Our research confirmed that COVID-19 related travel restrictions and separation from overseas family responsibilities and support structures, may also impact staff along with women in their care. This may create an added stress to clinicians in these settings.

Beneficence principles merge with altruism as many staff in our study were carers of young children and older relatives, therefore highly concerned with the risk their work posed to those in their care. Women are more likely have increased family responsibilities during the pandemic particularly increased hours on childcare, escalating the stress and complexity of their lives [50]. It should be considered that the cumulative impact of increased family responsibilities and stress associated with healthcare work put this group at particular mental illness risk during the pandemic [14]. Our study has illustrated that some clinicians dealt with this increased risk to their mental health by inventing activities and practices we coined as “rituals of keeping safe mentally”, activities of self-care that maintained or enhanced their personal well-being, some related to symbolic or real practices of infection control, others related to calming or pleasurable non-COVID related activities or exercise.

The capacity for large complex institutions to be flexible and have agile proactive policies, require time and consideration that pandemic conditions often precluded. At the time of this study the primary restrictions within the maternity service was on the number of support people and appeared highly restrictive due to low to no cases of COVID-19 in the community. However, the study period restrictions and preparations has allowed for a rapid and appropriate clinical escalation of restrictions in response to the current mid-2021 surge in COVID-19 cases in the local area. Therefore, it may be considered as beneficial to the system to have prioritised restrictions in preparedness. This study adds to understanding these issues and experiences and may assist in future planning and optimising service delivery that ensure that women-centred care is optimised as soon as possible in changing conditions.

Strengths and limitations

This study explored clinicians’ experience in a single centre, and this can be considered both a strength as rich contextualised detailed data was able to be collected, but it also brings a limitation to transferability. As, to the best of our knowledge, no other research has been conducted on a similar culturally diverse clinician group in Australia, it is difficult to say whether or how these findings may compare or be generalisable to other clinician groups servicing a diverse migrant population.

Some memory bias may have occurred as all interviews were conducted in a COVID-19 ‘lull’ during loosening of community restrictions with no local lockdowns. A significant portion of clinical systems discussions were concerning the first few weeks of the COVID-19 initial outbreak that had occurred up to seven months prior. There is always the limitation in qualitative studies of missing divergent opinions of participants who are unwilling to be interviewed. As management was supportive of the study and interviews could be conducted during work time, there appeared to be a general willingness from clinicians to participate in this study. Once participants gave informed consent all continued to the interview, after a suitable time was arranged.

The inclusion of both medical and midwifery clinicians as key informants is considered a strength of this study as well as inclusion of a variety of areas of maternity care and experience for rich data and perspectives.

Conclusion

The global COVID-19 pandemic highlights the vulnerability of maternity care to migrant communities and their tenuous support networks. Providing quality maternity care for all women in a pandemic is problematic. However, in high-migrant populations heath care providers need to be aware of the significant and often long-term support role overseas relatives play for women during pregnancy, birth and early infancy. Clinicians should be aware the loss of this support during the COVID-19 pandemic is ongoing and requires culturally competent care, possible extra antenatal education and psychosocial support.

To assist with maternity clinicians complying with hospital infectious control protocols during the pandemic, the health policies of relevant institutions should communicate effectively and strive to be compatible with community social distancing and other pandemic control measures.

Author agreement

The authors listed on this research agree: This manuscript is original work and has not received prior publication or under consideration by any other journal. All authors have seen and approved the manuscript and this submission. All authors abide by the copyright terms and conditions of Elsevier and the Australian College of Midwives

Ethical statement

Western Sydney Local Health District Human Research and Ethics Committee approval was granted for this research on (2020/ETH02074) 23 September 2020.

Funding

A two-year grant was awarded to SJ Melov by the Westmead Hospital Charitable Trust. Some funds from this grant were used to support this research: professional transcription and back-fill of substantive CMC role. The funding body had no role in study design, analysis or manuscript development.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare they have no conflicts of interest for the research presented in this manuscript.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Sarah J. Melov: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Nelma Galas: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing. Julie Swain: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing. Thushari I. Alahakoon: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing. Vincent Lee: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing. N Wah Cheung: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing. Terry McGee: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing. Dharmintra Pasupathy: Supervision, Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing - review & editing, . Justin McNab: Supervision, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all clinicians who gave their precious and valuable time to be interviewed for this study. We acknowledge and appreciate the support from the funding body. Appreciate the assistance Tony Melov gave with designing the figure graphic.

References

- 1.Goldberg J. 2016. It Takes A Village To Determine The Origins Of An African Proverb.https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2016/07/30/487925796/it-takes-a-village-to-determine-the-origins-of-an-african-proverb Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prime Minister of Australia Border Restriction Media Release (2020). Available from: https://www.pm.gov.au/media/border-restrictions.

- 3.Cutler D.M., Summers L.H. The COVID-19 pandemic and the $16 trillion virus. JAMA. 2020;324(15):1495–1496. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.19759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID Data Tracker. Available from: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#global-counts-rates.

- 5.Sanmarchi F., Golinelli D., Lenzi J., et al. Exploring the gap between excess mortality and COVID-19 deaths in 67 countries. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(7) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.17359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stanaway F., Irwig L., Teixeira-Pinto A., Bell K.J.L. COVID-19: how many Australians might have died if we’d had an outbreak like that in England and Wales? Med. J. Aust. 2021;214(2) doi: 10.5694/mja2.50909. 95–95.e91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shearer F.M., Gibbs L., Alisic E., et al. Survey Wave 1, May 2020. The University of Melbourne: Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity; 2020. Distancing measures in the face of COVID-19 in Australia summary of national survey findings. [Google Scholar]

- 8.John Hopkins University, Corona Virus Resource Center. Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/region.

- 9.B. News What’s gone wrong with Australia’s vaccine rollout? (17.7.21) Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-56825920.

- 10.M. Read Where COVID-19 is taking hold in Victoria and NSW (22.7.21) Available from: https://www.afr.com/politics/where-covid-19-is-taking-hold-in-victoria-and-nsw-20210722-p58byh.

- 11.Bradfield Z., Hauck Y., Homer C.S.E., et al. Midwives’ experiences of providing maternity care during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. Women Birth. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2021.02.007. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.González-Timoneda A., Hernández Hernández V., Pardo Moya S., Alfaro Blazquez R. Experiences and attitudes of midwives during the birth of a pregnant woman with COVID-19 infection: a qualitative study. Women Birth. 2021;34(5):465–472. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2020.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bradfield Z., Wynter K., Hauck Y., et al. Experiences of receiving and providing maternity care during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia: a five-cohort cross-sectional comparison. PLoS One. 2021;16(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dobson H., Malpas C.B., Burrell A.J., et al. Burnout and psychological distress amongst Australian healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Australas. Psychiatry. 2021;29(1):26–30. doi: 10.1177/1039856220965045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Altman M.R., Gavin A.R., Eagen-Torkko M.K., Kantrowitz-Gordon I., Khosa R.M., Mohammed S.A. Where the system failed: the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on pregnancy and birth care. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2021;8 doi: 10.1177/23333936211006397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ollivier R., Aston D.M., Price D.S., et al. Mental health & parental concerns during COVID-19: the experiences of new mothers amidst social isolation. Midwifery. 2021;94 doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2020.102902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centre for Epidemiology and Evidence . NSW Government; 2021. Mothers and Babies 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melov S.J., Hitos K. Venous thromboembolism risk and postpartum lying-in: acculturation of Indian and Chinese women. Midwifery. 2018;58:13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braun V., Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exercise Health. 2019;11(4):589–597. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Regional population: Statistics about the population and components of change (births, deaths, migration) for Australia’s capital cities and regions. Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/regional-population/latest-release#new-south-wales.

- 21.Western Sydney Local Helath District, About Us. Available from: https://www.wslhd.health.nsw.gov.au/About-Us.

- 22.Patton M.Q. fouth edn. Thousand Oaks, SAGE Publications, Inc.; California: 2015. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods Integrating Theory and Practice. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clarke V., Braun V. SAGE; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2013. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vasilevski V., Sweet L., Bradfield Z., et al. Receiving maternity care during the COVID-19 pandemic: experiences of women’s partners and support persons. Women Birth. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2021.04.012. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riggs E., Davis E., Gibbs L., et al. Accessing maternal and child health services in Melbourne, Australia: reflections from refugee families and service providers. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012;12(1):117. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niles P.M., Asiodu I.V., Crear-Perry J., et al. Reflecting on equity in perinatal care during a pandemic. Health Equity. 2020;4(1):330–333. doi: 10.1089/heq.2020.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mengesha Z.B., Perz J., Dune T., Ussher J. Refugee and migrant women’s engagement with sexual and reproductive health care in Australia: a socio-ecological analysis of health care professional perspectives. PLoS One. 2017;12(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.L. Smith. 2019–20 Australian bushfires—frequently asked questions: a quick guide (12 March 2020) Available from: https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1920/Quick_Guides/AustralianBushfires.

- 29.Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia . Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2019. Summary of Findings.https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/disability/disability-ageing-and-carers-australia-summary-findings/latest-release#carers Summary of Findings. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 30.United Nations, Population Facts; Sept 2019. Dept of Economic and Social Affairs. Available from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/publications/populationfacts/docs/MigrationStock2019_PopFacts_2019-04.pdf.

- 31.Australian Government, Australian Bureau of Statistics; Census reveals a fast changing, culturally diverse nation. Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/lookup/media%20release3.

- 32.Khalil A., Rezende J., Akolekar R., Syngelaki A., Nicolaides K.H. Maternal racial origin and adverse pregnancy outcome: a cohort study. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;41(3):278–285. doi: 10.1002/uog.12313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heslehurst N., Brown H., Pemu A., Coleman H., Rankin J. Perinatal health outcomes and care among asylum seekers and refugees: a systematic review of systematic reviews. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):89. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1064-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Valtorta N.K., Kanaan M., Gilbody S., Ronzi S., Hanratty B. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart. 2016;102(13):1009–1016. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loprinzi P.D., Ford M.A. Effects of social support network size on mortality risk: considerations by diabetes status. Diabetes Spectr. 2018;31(2):189–192. doi: 10.2337/ds17-0056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holt-Lunstad J., Smith T.B., Layton J.B. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feeney B.C., Collins N.L. A new look at social support: a theoretical perspective on thriving through relationships. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2015;19(2):113–147. doi: 10.1177/1088868314544222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lippold M.A., Glatz T., Fosco G.M., Feinberg M.E. Parental perceived control and social support: linkages to change in parenting behaviors during early adolescence. Fam. Process. 2018;57(2):432–447. doi: 10.1111/famp.12283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.A. Greenbank: Partners feeling ‘helpless’ after being banned from visiting newborns at Western Sydney hospitals amid COVID outbreak. In: ABC News. online; Thu 15 Jul 2021.

- 40.Gorski H.P., Kamimura A., Nourian M., Assasnik N., Wright L., Franckek-Roa K. Gender roles and women’s health in India. Public Policy Adm. Res. 2017;7:12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patel V., Kirkwood B.R., Pednekar S., et al. Gender disadvantage and reproductive health risk factors for common mental disorders in women: a community survey in India. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2006;63(4):404–413. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crepinsek M., Bell R., Graham I., Coutts R. Towards a conceptualisation of woman centred care — a global review of professional standards. Women Birth. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2021.02.005. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Department of Health . Australian Government; Canberra: 2020. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Pregnancy Care. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Midwife Standards for Practice . 2018. Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia.https://www.nursingmidwiferyboard.gov.au/Codes-Guidelines-Statements/Professional-standards/Midwife-standards-for-practice.aspx Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 45.Australian Government Department of Health; 2019. Woman-Centred Care: Strategic Directions for Australian Maternity Services.https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/woman-centred-care-strategic-directions-for-australian-maternity-services Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leap N. Woman-centred or women-centred care: does it matter? Br. J. Midwifery. 2009;17(1):12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rigg E., Dahlen H.G. Woman centred care: has the definition been morphing of late? Women Birth. 2021;34(1):1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2020.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lamb D., Gnanapragasam S., Greenberg N., et al. Psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on 4378 UK healthcare workers and ancillary staff: initial baseline data from a cohort study collected during the first wave of the pandemic. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021;78(11):801–808. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2020-107276. oemed-2020-107276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Glannon W., Ross L.F. Are doctors altruistic? J. Med. Ethics. 2002;28(2):68–69. doi: 10.1136/jme.28.2.68. discussion 74-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Johnston R.M., Mohammed A., van der Linden C. Evidence of exacerbated gender inequality in child care obligations in Canada and Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Polit. Gend. 2020;16(4):1131–1141. [Google Scholar]