Abstract

Background

Management of rotator cuff disease often includes manual therapy and exercise, usually delivered together as components of a physical therapy intervention. This review is one of a series of reviews that form an update of the Cochrane review, 'Physiotherapy interventions for shoulder pain'.

Objectives

To synthesise available evidence regarding the benefits and harms of manual therapy and exercise, alone or in combination, for the treatment of people with rotator cuff disease.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2015, Issue 3), Ovid MEDLINE (January 1966 to March 2015), Ovid EMBASE (January 1980 to March 2015), CINAHL Plus (EBSCO, January 1937 to March 2015), ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO ICTRP clinical trials registries up to March 2015, unrestricted by language, and reviewed the reference lists of review articles and retrieved trials, to identify potentially relevant trials.

Selection criteria

We included randomised and quasi‐randomised trials, including adults with rotator cuff disease, and comparing any manual therapy or exercise intervention with placebo, no intervention, a different type of manual therapy or exercise or any other intervention (e.g. glucocorticoid injection). Interventions included mobilisation, manipulation and supervised or home exercises. Trials investigating the primary or add‐on effect of manual therapy and exercise were the main comparisons of interest. Main outcomes of interest were overall pain, function, pain on motion, patient‐reported global assessment of treatment success, quality of life and the number of participants experiencing adverse events.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected trials for inclusion, extracted the data, performed a risk of bias assessment and assessed the quality of the body of evidence for the main outcomes using the GRADE approach.

Main results

We included 60 trials (3620 participants), although only 10 addressed the main comparisons of interest. Overall risk of bias was low in three, unclear in 14 and high in 43 trials. We were unable to perform any meta‐analyses because of clinical heterogeneity or incomplete outcome reporting. One trial compared manual therapy and exercise with placebo (inactive ultrasound therapy) in 120 participants with chronic rotator cuff disease (high quality evidence). At 22 weeks, the mean change in overall pain with placebo was 17.3 points on a 100‐point scale, and 24.8 points with manual therapy and exercise (adjusted mean difference (MD) 6.8 points, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.70 to 14.30 points; absolute risk difference 7%, 1% fewer to 14% more). Mean change in function with placebo was 15.6 points on a 100‐point scale, and 22.4 points with manual therapy and exercise (adjusted MD 7.1 points, 95% CI 0.30 to 13.90 points; absolute risk difference 7%, 1% to 14% more). Fifty‐seven per cent (31/54) of participants reported treatment success with manual therapy and exercise compared with 41% (24/58) of participants receiving placebo (risk ratio (RR) 1.39, 95% CI 0.94 to 2.03; absolute risk difference 16% (2% fewer to 34% more). Thirty‐one per cent (17/55) of participants reported adverse events with manual therapy and exercise compared with 8% (5/61) of participants receiving placebo (RR 3.77, 95% CI 1.49 to 9.54; absolute risk difference 23% (9% to 37% more). However adverse events were mild (short‐term pain following treatment).

Five trials (low quality evidence) found no important differences between manual therapy and exercise compared with glucocorticoid injection with respect to overall pain, function, active shoulder abduction and quality of life from four weeks up to 12 months. However, global treatment success was more common up to 11 weeks in people receiving glucocorticoid injection (low quality evidence). One trial (low quality evidence) showed no important differences between manual therapy and exercise and arthroscopic subacromial decompression with respect to overall pain, function, active range of motion and strength at six and 12 months, or global treatment success at four to eight years. One trial (low quality evidence) found that manual therapy and exercise may not be as effective as acupuncture plus dietary counselling and Phlogenzym supplement with respect to overall pain, function, active shoulder abduction and quality life at 12 weeks. We are uncertain whether manual therapy and exercise improves function more than oral non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAID), or whether combining manual therapy and exercise with glucocorticoid injection provides additional benefit in function over glucocorticoid injection alone, because of the very low quality evidence in these two trials.

Fifty‐two trials investigated effects of manual therapy alone or exercise alone, and the evidence was mostly very low quality. There was little or no difference in patient‐important outcomes between manual therapy alone and placebo, no treatment, therapeutic ultrasound and kinesiotaping, although manual therapy alone was less effective than glucocorticoid injection. Exercise alone led to less improvement in overall pain, but not function, when compared with surgical repair for rotator cuff tear. There was little or no difference in patient‐important outcomes between exercise alone and placebo, radial extracorporeal shockwave treatment, glucocorticoid injection, arthroscopic subacromial decompression and functional brace. Further, manual therapy or exercise provided few or no additional benefits when combined with other physical therapy interventions, and one type of manual therapy or exercise was rarely more effective than another.

Authors' conclusions

Despite identifying 60 eligible trials, only one trial compared a combination of manual therapy and exercise reflective of common current practice to placebo. We judged it to be of high quality and found no clinically important differences between groups in any outcome. Effects of manual therapy and exercise may be similar to those of glucocorticoid injection and arthroscopic subacromial decompression, but this is based on low quality evidence. Adverse events associated with manual therapy and exercise are relatively more frequent than placebo but mild in nature. Novel combinations of manual therapy and exercise should be compared with a realistic placebo in future trials. Further trials of manual therapy alone or exercise alone for rotator cuff disease should be based upon a strong rationale and consideration of whether or not they would alter the conclusions of this review.

Keywords: Adult, Humans, Male, Middle Aged, Musculoskeletal Manipulations, Rotator Cuff, Exercise Therapy, Exercise Therapy/methods, Muscular Diseases, Muscular Diseases/therapy, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Shoulder Pain, Shoulder Pain/etiology, Shoulder Pain/therapy

Plain language summary

Manual therapy and exercise for rotator cuff disease

Background

Rotator cuff disease is a common cause of shoulder pain. People with rotator cuff disease often describe their pain as being worse at night and exacerbated by movement in specific directions including overhead activity. It is often associated with loss of function and some people describe weakness.

Manual therapy comprises movement of the joints and other structures by a healthcare professional (e.g. physiotherapist). Exercise includes any purposeful movement of a joint, muscle contraction or prescribed activity. The aims of both treatments are to relieve pain, increase strength and joint range, and improve function.

Study characteristics

This summary of an updated Cochrane review presents what we know from research about the benefits and harms of manual therapy and exercise compared with placebo, no intervention or any other intervention in people with rotator cuff disease. After searching for all relevant studies published up to March 2015, we included 60 trials (3620 participants), however only 10 looked at manual therapy and exercise in combination. Among the included participants, 52% were women, average age was 51 years and average duration of the condition was 11 months. The average duration of manual therapy and exercise interventions was six weeks.

Key results: one trial of manual therapy and exercise compared with placebo (inactive ultrasound therapy) for 10 weeks in people with chronic rotator cuff disease

Overall pain (higher scores mean more improvement in pain reduction)

People who had manual therapy and exercise had improvements in pain that were little or no different to people who had placebo. Improvement in pain was 6.8 points more (ranging from 0.7 points less to 14.3 points more) at 22 weeks (7% absolute improvement).

People who had manual therapy and exercise rated their change in pain score as 24.8 points on a scale of 0 to 100 points.

People who had placebo rated their change in pain score as 17.3 points on a scale of 0 to 100 points.

Function (higher scores mean more improvement in function)

People who had manual therapy and exercise improved slightly more than people who had placebo. Improvement in function was 7.1 points more (ranging from 0.3 to 13.9 points more) at 22 weeks (7% absolute improvement).

People who had manual therapy and exercise rated their change in function as 22.4 points on a scale of 0 to 100 points.

People who had placebo rated their change in function as 15.6 points on a scale of 0 to 100 points.

Treatment success

16 more people out of 100 rated their treatment as successful with manual therapy and exercise compared with placebo, 16% absolute improvement (ranging from 2% less to 34% more improvement).

Fifty‐seven out of 100 people reported treatment success with manual therapy and exercise.

Forty‐one out of 100 people reported treatment success with placebo.

Side effects

23 more people out of 100 people had minor side effects such as temporary pain after treatment with manual therapy and exercise compared with placebo.

Thirty‐one out of 100 people reported side effects with manual therapy and exercise.

Eight out of 100 people reported side effects with placebo.

Quality of the evidence

High quality evidence from one trial suggested that manual therapy and exercise improved function only slightly more than placebo at 22 weeks, was little or no different to placebo in terms of other patient‐important outcomes (e.g. overall pain), and was associated with relatively more frequent but mild adverse events.

Low quality evidence suggested that there may be little or no difference in overall pain and function when manual therapy and exercise is compared with glucocorticoid injection, there may be little or no difference in overall pain and function when manual therapy and exercise is compared with arthroscopic subacromial decompression, and people who receive acupuncture plus dietary counselling and Phlogenzym supplement may have less pain and better function than people receiving manual therapy and exercise.

We are uncertain whether firstly, manual therapy and exercise improves function more than oral non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAID), and secondly, combining manual therapy and exercise with glucocorticoid injection provides additional improvement in function over glucocorticoid injection alone, because the quality of the evidence was very low.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Manual therapy and exercise compared to placebo for rotator cuff disease.

| Manual therapy and exercise compared to placebo for rotator cuff disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: rotator cuff disease Settings: Public hospital physiotherapy units and private physiotherapy practices, Australia Intervention: soft tissue massage, glenohumeral joint mobilisation, thoracic spine mobilisation, cervical spine mobilisation, scapular retraining, postural taping and supervised exercises in 10 sessions over 10 weeks along with home exercises for 22 weeks Comparison: inactive ultrasound therapy and application of an inert gel in 10 sessions over 10 weeks | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | manual therapy and exercise | |||||

|

Overall pain Assessed with SPADI pain score Scale from 0‐100 (higher score denotes less pain) Follow‐up: 22 weeks |

The mean improvement in overall pain score in the control group was 17.31 | The mean improvement in overall pain score in the intervention group was 6.8 points higher (‐0.7 lower to 14.3 higher) | ‐ | 120 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | Absolute risk difference 7% (1% fewer to 14% more); relative percentage change 14% (1% fewer to 30% more) NNTB not applicable |

|

Function Assessed with SPADI total score Scale from 0‐100 (higher score denotes greater function) Follow‐up: 22 weeks |

The mean improvement in function score in the control group was 15.61 | The mean improvement in function score in the intervention group was 7.1 points higher (0.3 higher to 13.9 higher) | ‐ | 120 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | Absolute risk difference 7% (1% to 14% more); relative percentage change 16% (1% to 32% more) NNTB 6 (3 to 103) |

|

Pain on motion Assessed with VAS Scale from 0‐10 (higher score denotes less pain) Follow‐up: 22 weeks |

The mean improvement in pain on motion score in the control group was 1.61 | The mean improvement in pain on motion score in the intervention group was 0.9 points higher (‐0.03 lower to 1.7 higher) | ‐ | 120 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | Absolute risk difference 9% (1% to 17% more); relative percentage change 18% (1% fewer to 35% more) NNTB not applicable |

|

Global assessment of treatment success Follow‐up: 22 weeks |

Study population | RR 1.39 (0.94 to 2.03) | 112 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | Absolute risk difference 16% (2% fewer to 34% more); relative percentage change 39% (6% fewer to 103% more) NNTB not applicable |

|

| 414 per 10002 | 575 per 1000 (393 to 840) | |||||

|

Quality of life Assessed with AQoL Scale from ‐0.4 to 1 (higher score denotes higher quality of life) Follow‐up: 22 weeks |

The mean improvement in quality of life score in the control group was 01 | The mean improvement in quality of life score in the intervention group was 0.07 points higher (0.04 higher to 0.1 higher) | ‐ | 120 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | Absolute risk difference 5% (3% to 7% more); relative percentage change 10% (5% to 14% more) NNTB not applicable |

|

Adverse events Follow‐up: 11 weeks |

Study population | RR 3.77 (1.49 to 9.54) | 116 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | Absolute risk difference 23% (9% to 37% more); relative percentage change 277% (49% to 854% more) NNTH 5 (26 to 2) Adverse events were mild, including short‐term pain during or after treatment in the clinic, short‐term pain after home exercises, or mild irritation with taping. |

|

| 82 per 10002 | 309 per 1000 (122 to 782) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

This table summarises data from the Bennell 2010 trial.

1Mean score in the placebo group in Bennell 2010 used as the assumed control group mean.

2Risk in placebo group in Bennell 2010 used as assumed risk

Summary of findings 2. Manual therapy and exercise compared to glucocorticoid injection for rotator cuff disease.

| Manual therapy and exercise compared to glucocorticoid injection for rotator cuff disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: rotator cuff disease Settings: Military hospital–based outpatient clinic, USA; Primary care (general practitioner), UK Intervention: Either joint and soft tissue mobilisation, manual stretches and supervised and home exercises twice a week for three weeks or active and passive mobilisation, home exercises and therapeutic ultrasound once a week for six weeks Comparison: glucocorticoid injection | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Glucocorticoid injection | manual therapy and exercise | |||||

|

Overall pain Assessed with NRS Scale from 0‐10 (lower score denotes less pain) Follow‐up: 1 month |

The mean overall pain score in the control group was 1.71 | The mean overall pain score in the intervention group was 0.1 points lower (0.92 lower to 0.72 higher) | ‐ | 88 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW2 | Absolute risk difference 1% (9% fewer to 7% more); relative percentage change 3% (28% fewer to 22% more) NNTB not applicable |

|

Function Assessed with SPADI total score Scale from 0‐100 (lower score denotes greater function) Follow‐up: 1 month |

The mean function score in the control group was 23.21 | The mean function score in the intervention group was 1 point lower (8.77 lower to 6.77 higher) | ‐ | 88 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW2 | Absolute risk difference 1% (9% fewer to 7% more); relative percentage change 2% (19% fewer to 15% more) NNTB not applicable |

| Pain on motion | See Comments column | See Comments column | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Outcome not measured |

|

Global assessment of treatment success Follow‐up: 6 weeks |

Study population | RR 0.33 (0.14 to 0.79) | 198 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW2,4 | Absolute risk difference 12% (21% to 3% fewer); relative percentage change 67% (86% to 21% fewer) NNTB 9 (7 to 26) |

|

| 184 per 10003 | 61 per 1000 (26 to 145) | |||||

|

Quality of life Assessed with Global Rating of Change Scale Scale from ‐7 to 7 (higher score denotes higher quality of life) Follow‐up: 1 month |

The mean quality of life score in the control group was 31 | The mean quality of life score in the intervention group was no different (1.37 lower to 1.37 higher) | ‐ | 88 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW2 | Absolute risk difference 0% (10% fewer to 10% more); relative percentage change 0% (46% fewer to 46% more) NNTB not applicable |

|

Adverse events Follow‐up: 12 months |

Study population | not estimable | 94 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW2 | "Other than transient pain from the CSI [injection], there were no other adverse events reported by patients in either group." | |

| 0 per 10005 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

This table summarises data from the Rhon 2014 and Hay 2003 trials.

1Mean score glucocorticoid injection group in Rhon 2014 used as assumed control group mean

2Downgraded (‐2) for risk of bias. Participants could not be blinded (risk of performance bias and detection bias)

3Risk in glucocorticoid injection group in Hay 2003 used as assumed risk

4Downgraded (‐1) for indirectness. Only 75% of participants had rotator cuff disease (25% had adhesive capsulitis)

5Risk in glucocorticoid injection group in Rhon 2014 used as assumed risk

Summary of findings 3. Manual therapy and exercise compared to arthroscopic subacromial decompression for rotator cuff disease.

| Manual therapy and exercise compared to arthroscopic subacromial decompression for rotator cuff disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: rotator cuff disease Settings: Hospital, Ringkjoebing County, Denmark Intervention: 12 weeks of manual therapy (soft tissue treatment) plus supervised exercises (stabilising and strengthening) Comparison: arthroscopic subacromial decompression | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Arthroscopic subacromial decompression | Manual therapy and exercise | |||||

|

Overall pain Assessed with Constant‐Murley pain score Scale from 0‐15 (higher score denotes less pain) Follow‐up: 6 months |

The mean improvement in overall pain score in the control group was 3.81 | The mean improvement in overall pain score in the intervention group was 0.1 lower (1.68 lower to 1.48 higher) | ‐ | 84 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW2 | Absolute risk difference 1% (11% fewer to 10% more); relative percentage change 2% (40% fewer to 35% more) NNTB not applicable |

|

Function Assessed with Constant‐Murley total score Scale from 0‐100 (higher score denotes greater function) Follow‐up: 6 months |

The mean improvement in function score in the control group was 19.91 | The mean improvement in function score in the intervention group was 1.4 points higher (7.63 lower to 10.43 higher) | ‐ | 84 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW2 | Absolute risk difference 1% (7% fewer to 10% more); relative percentage change 4% (23% fewer to 31% more) NNTB not applicable |

| Pain on motion | See Comments column | See Comments column | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Outcome not measured |

|

Global assessment of treatment success Follow‐up: 4‐8 years |

Study population | RR 1.14 (0.82 to 1.61) | 79 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW2 | Absolute risk difference 9% (13% fewer to 30% more); relative percentage change 14% (18% fewer to 61% more) | |

| 590 per 10003 | 673 per 1000 (484 to 950) | |||||

| Quality of life | See Comments column | See Comments column | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Outcome not measured |

| Adverse events | See Comments column | See Comments column | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Outcome not measured |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

This table summarises data from the Haahr 2005 trial.

1Mean score in arthroscopic subacromial decompression group in Haahr 2005 used as assumed control group risk

2Downgraded (‐2) for risk of bias. Participants were not blinded (risk of performance and detection bias)

3Risk in arthroscopic subacromial decompression group in Haahr 2005 used as assumed risk

Background

Description of the condition

This review is one in a series of reviews aiming to determine the evidence for efficacy of common interventions for shoulder pain. This series of reviews form the update of an earlier Cochrane review of physical therapy for shoulder disorders (Green 2003). Since our original review, many new clinical trials studying a diverse range of interventions have been performed. To improve usability of the review, we have subdivided the reviews by type of shoulder disorder, as patients within different diagnostic groupings may respond variably to different interventions. This review focuses on manual therapy and exercise interventions alone or in combination for rotator cuff disease. A separate review of electrotherapy modalities for rotator cuff disease is underway. Reviews of manual therapy and exercise for adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder) (Page 2014a) and electrotherapy modalities for adhesive capsulitis (Page 2014b) were published in 2014.

Shoulder pain is common, with a point prevalence ranging from 7% to 26% in the general population (Luime 2004). Although not life‐threatening, it impacts on the performance of tasks essential to daily living (such as dressing, personal hygiene, eating and work), and often results in substantial utilisation of healthcare resources (Largacha 2006; Mroz 2014; Van der Heijden 1999; Virta 2012). The most common cause of shoulder pain in primary care is disorders of the rotator cuff (Linsell 2006; Ostör 2005), which comprises the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis and teres minor muscles. These muscles facilitate both movement and dynamic stabilisation of the shoulder joint (Whittle 2015).

Numerous diagnostic labels have been used in the literature to describe disorders of the rotator cuff (for example, subacromial impingement syndrome, rotator cuff tendinopathy or tendinitis, partial or full rotator cuff tear, calcific tendinitis and subacromial bursitis) but the terms are not standardised (Schellingerhout 2008). The term 'rotator cuff disease' was proposed as an umbrella term to classify disorders of the rotator cuff regardless of the cause of disorder (e.g. degeneration or acute injury) and specific anatomical location (Buchbinder 1996; Whittle 2015).

People with rotator cuff disease often describe their shoulder pain as being worse at night and exacerbated by overhead activity, and some describe weakness or loss of function; however, there are few data regarding the diagnostic accuracy of individual symptoms in rotator cuff disease without tears (Whittle 2015). In addition to history‐taking and clinical evaluation, the use of physical examination manoeuvres has been recommended for the diagnosis of rotator cuff disease. A systematic review of diagnostic test accuracy studies found that a positive painful arc test result and a positive external rotation resistance test result were the most accurate findings for detecting rotator cuff disease, whereas the presence of a positive lag test result (external or internal rotation) was most accurate for diagnosis of a full‐thickness rotator cuff tear (Hermans 2013).

Rotator cuff disease has been found to increase in prevalence with age (Yamamoto 2010) and in those participating in occupational or sporting activities (e.g. swimming, tennis) that require repetitive overhead use of the arms (Edmonds 2014; Walker 2012). The condition is often self‐limiting (Reilingh 2008; Whittle 2015), though 14% of patients, particularly the elderly, have been found to continue consulting their GP for shoulder pain beyond two years after initial presentation (Linsell 2006).

Description of the intervention

Manual therapy and exercise, usually delivered together as components of a physical therapy intervention, are commonly used in the management of rotator cuff disease (Whittle 2015). Manual therapy includes any clinician‐applied movement of the joints and other structures, for example mobilisation (of which several types exist, e.g. Kaltenborn 1976; Maitland 1977) or manipulation. Exercise includes any purposeful movement of a joint, muscle contraction or prescribed activity, which may be performed under the supervision of a clinician or unsupervised at home. Commonly prescribed exercises include range of motion (ROM), stretching, stabilising and strengthening (Dewhurst 2010).

Manual therapy and exercise are delivered by various clinicians, including physiotherapists, physical therapists, chiropractors, and osteopaths. The aims of both types of interventions are to improve function, promote healing, increase joint range, strengthen weakened muscles and correct imbalance in the stabilising function of the rotator cuff (Brantingham 2011; Kelly 2010; Kuhn 2009). In practice, people with rotator cuff disease seldom receive a single intervention in isolation (i.e. manual therapy alone or exercise alone) (Dziedzic 1999; Glazier 1998; Kooijman 2013; Roberts 2014). Often, electrotherapy modalities (e.g. therapeutic ultrasound, laser therapy) are also delivered as part of a multimodal physical therapy intervention (Kooijman 2013; Struyf 2012), and manual therapy and exercise may also be used in conjunction with other interventions such as non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or glucocorticoid injection, or both.

How the intervention might work

Manual therapy and exercise interventions are hypothesised to produce a number of beneficial physiological and biomechanical effects. Manual therapy is employed to reduce pain by stimulating peripheral mechanoreceptors and inhibiting nociceptors, and to increase joint mobility by enhancing exchange between synovial fluid and cartilage matrix (Bialosky 2009). Exercise aims to improve muscle function and range of motion by restoring shoulder mobility, proprioception and stability (Kay 2012).

When delivered together, it is unclear whether the effects of manual therapy with exercise represent the effects of manual therapy, the effects of exercise, or an interaction between the two. It has been suggested that the short‐term analgesic effects of manual therapy may allow people with other musculoskeletal conditions (e.g. neck pain) to perform exercises designed to produce long‐term changes in muscle function and range of motion (Miller 2010; Miller 2014). A similar mechanism of action may occur in people with rotator cuff disease.

Why it is important to do this review

The previous version of this review (Green 2003) included four trials investigating the efficacy of manual therapy or exercise (or both) for rotator cuff disease (Bang 2000; Brox 1993; Conroy 1998; Winters 1997), and concluded that firstly, exercise alone was more effective than placebo and secondly, mobilisation was an effective add‐on to exercise for people with this condition. However, it was unclear whether manual therapy alone, or manual therapy and exercise, were effective. Many new trials have been published since the 2003 review (as summarised in recent systematic reviews, including Brantingham 2011, Braun 2013, Gebremariam 2014, Hanratty 2012, Littlewood 2012 and Van den Dolder 2014). To best inform current practice, an up‐to‐date review which incorporates the most recently available evidence is needed.

Objectives

To synthesise available evidence regarding the benefits and harms of manual therapy and exercise, alone or in combination, for the treatment of people with rotator cuff disease.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of any design (e.g. parallel, cross‐over, factorial) and controlled clinical trials using a quasi‐randomised method of allocation, such as by alternation or date of birth. Reports of trials were eligible regardless of the language or date of publication.

Types of participants

We included trials that recruited adults (> 16 years of age) with rotator cuff disease, as defined by the authors (e.g. using terminology such as subacromial impingement syndrome, rotator cuff tendonitis or tendinopathy, supraspinatus, infraspinatus or subscapularis tendonitis, subacromial bursitis, or rotator cuff tears), for any duration.

We also included trials with participants with unspecified shoulder pain provided that the inclusion/exclusion criteria were compatible with a diagnosis of rotator cuff disease. If trials included participants with either rotator cuff disease or adhesive capsulitis, we attempted to retrieve the data for rotator cuff disease participants from the trialists; if unsuccessful, we included the trial only if more than 75% of participants had rotator cuff disease.

We excluded trials that included any participants with a history of significant trauma or systemic inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, hemiplegic shoulders, or pain in the shoulder region as part of a complex myofascial neck/shoulder/arm pain condition.

Types of interventions

We included trials comparing any manual therapy or exercise intervention to placebo, no treatment, a different type of manual therapy or exercise, or another active intervention (e.g. glucocorticoid injection). Trials evaluating the primary or add‐on effects of manual therapy and exercise, manual therapy alone, and exercise alone were eligible.

Eligible manual therapy interventions included mobilisation, manipulation and massage. Eligible exercise interventions included supervised or home exercises, which could be land‐based or water‐based, but had to comprise tailored shoulder exercises rather than just general activity, for example, swimming.

We excluded trials primarily evaluating the effect of electrotherapy modalities such as therapeutic ultrasound, laser therapy, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), pulsed electromagnetic field therapy, interferential current, phonophoresis, iontophoresis, or short wave diathermy. Electrotherapy modalities for rotator cuff disease have been analysed in a separate Cochrane review.

Types of outcome measures

We did not consider outcomes as part of the eligibility criteria.

Main outcomes

Overall pain (mean or mean change measured by visual analogue scale (VAS), numerical or categorical rating scale).

-

Function. Where trialists reported outcome data for more than one function scale, we extracted data on the scale that was highest on the following a priori defined list:

Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI) (Roach 1991);

Croft Shoulder Disability Questionnaire (Croft 1994);

Constant‐Murley Score (Constant 1987);

any other shoulder‐specific function scale.

Pain on motion measured by VAS, numerical or categorical rating scale.

Global assessment of treatment success as defined by the trialists (e.g. proportion of participants with significant overall improvement).

Quality of life as measured by generic measures (such as components of the Short Form‐36 (SF‐36)) or disease‐specific tools).

Number of participants experiencing an adverse event in the trial (however defined by the authors).

Other outcomes

Night pain measured by VAS, numerical or categorical rating scale.

Pain with resisted movement measured by VAS, numerical or categorical rating scale.

Range of motion (ROM) (e.g. flexion, abduction, external rotation and internal rotation (measured in degrees or other e.g. hand‐behind‐back distance in centimetres)). Where trialists reported outcome data for both active and passive ROM measures, we extracted the data on active ROM only.

Strength.

Work disability.

Surgery (e.g. surgical decompression, rotator cuff repair).

We extracted efficacy outcome measures (e.g. function or overall pain) at the following time points:

up to three weeks;

longer than three and up to six weeks (this was the main time point);

longer than six weeks and up to six months, and;

longer than six months.

If data were available in a trial at multiple time points within each of the above periods (e.g. at four, five, and six weeks), we only extracted data at the latest possible time point of each period.

We extracted adverse events reported at all time points.

We collated the main results of the review into 'Summary of findings' (SoF) tables which provide key information concerning the quality of evidence and the magnitude and precision of the effect of the interventions. We included the main outcomes (see above) in the SoF tables, with results at, or nearest, the main time point (six weeks) presented.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; The Cochrane Library 2015, Issue 3), Ovid MEDLINE (January 1966 to March 2015), Ovid EMBASE (January 1980 to March 2015), and CINAHL Plus (EBSCO, January 1937 to March 2015). The complete search strategies are presented in Appendix 1. Note that the search terms used also included clinical terms relevant to adhesive capsulitis and electrotherapy interventions as the current review and Cochrane reviews of electrotherapy modalities for rotator cuff disease, manual therapy and exercise for adhesive capsulitis, and electrotherapy modalities for adhesive capsulitis, were conducted simultaneously.

Searching other resources

We searched for ongoing trials and protocols of published trials in the clinical trials registry that is maintained by the US National Institute of Health (http://clinicaltrials.gov) and the Clinical Trial Registry at the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform of the World Health Organization (http://www.who.int/ictrp/en/). We also reviewed the reference lists of the included trials and any relevant review articles retrieved from the electronic searches, to identify any other potentially relevant trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (MJP and BM) independently selected trials for possible inclusion against a predetermined checklist of inclusion criteria (see Criteria for considering studies for this review). We screened titles and abstracts and initially categorised studies into the following groups.

Possibly relevant: trials that met the inclusion criteria and trials from which it was not possible to determine whether they met the criteria either from their title or abstract.

Excluded: those clearly not meeting the inclusion criteria.

If a title or abstract suggested that the trial was eligible for inclusion, or we could not tell, we obtained a full‐text version of the article and two review authors (MJP and BM) independently assessed it to determine whether it met the inclusion criteria. The review authors resolved discrepancies through discussion or adjudication by a third author (SG or RB).

Data extraction and management

Pairs of review authors (MJP, BM, SS, JD, NL and MM) independently extracted data using a standard data extraction form developed for this review. The authors resolved any discrepancies through discussion or adjudication by a third author (SG or RB), until consensus was reached. We pilot tested the data extraction form and modified it accordingly before use. In addition to items for assessing risk of bias and numerical outcome data, we also recorded the following characteristics.

Trial characteristics, including type (e.g. parallel or cross‐over), country, source of funding, and trial‐registration status (with registration number recorded if available).

Participant characteristics, including age, sex, duration of symptoms, and inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Intervention characteristics, including type of manual therapy or exercise, duration of treatment, use of co‐interventions.

Outcomes reported, including the measurement instrument used and timing of outcome assessment.

One author (MJP) compiled all comparisons and entered outcome data into Review Manager (RevMan) 5.3 (RevMan 2014).

For a particular systematic review outcome there may be multiple results available in the trial reports (e.g. from multiple scales, time points and analyses). To prevent selective inclusion of data based on the results (Page 2013), we used the following a priori‐defined decision rules to select data from trials.

Where trialists reported analysis of covariance‐ (ANCOVA) adjusted mean differences along with either final values and change from baseline values for the same continuous outcome, we extracted ANCOVA‐adjusted mean differences.

Where trialists reported final values and change from baseline values for the same continuous outcomes, we extracted final values.

Where trialists reported data analysed based on the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) sample and another sample (e.g. per‐protocol, as‐treated), we extracted ITT‐analysed data;

For cross‐over RCTs, we extracted data from the first period only.

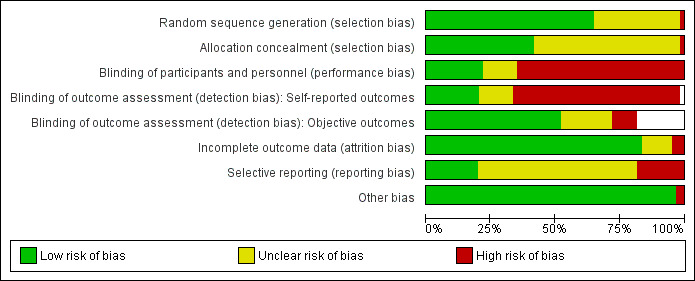

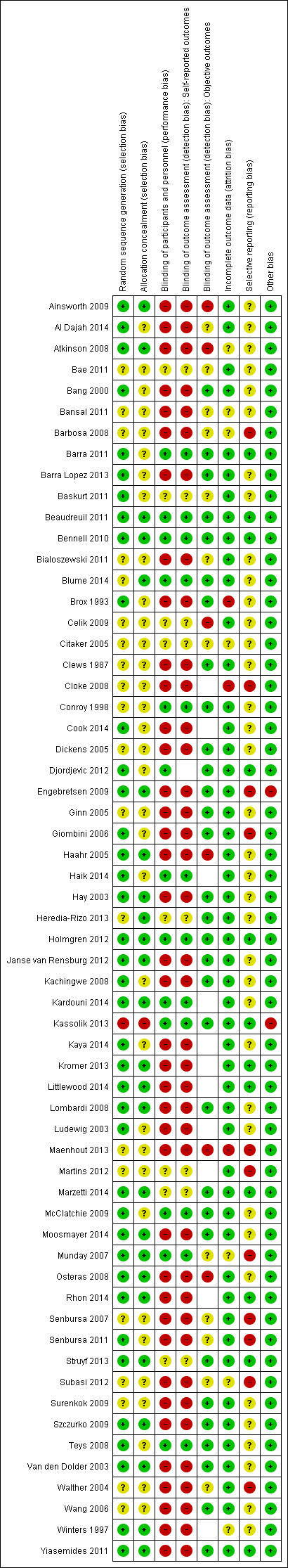

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Pairs of review authors (MJP, BM, SS, JD, NL and MM) independently assessed the risk of bias in included trials using The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias, as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We assessed the following domains.

Random sequence generation.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding of participants and personnel.

Blinding of outcome assessment (assessed separately for self‐reported and objectively assessed outcomes).

Incomplete outcome data.

Selective reporting.

Other sources of bias (for example, baseline imbalance).

We rated each item as being at 'low risk', 'unclear risk' or 'high risk' of bias. We classified the overall risk of bias as low if all domains were at low risk of bias, as high if at least one domain was at high risk of bias, or as unclear if at least one domain was at unclear risk of bias and no domain was at high risk. We assessed the selective reporting domain for all trials, and documented it in the risk of bias tables, but did not consider it in the overall risk of bias judgement if the only types of selective reporting identified were non‐ or partial reporting of outcomes. Non‐ or partial reporting of outcomes biases the results of meta‐analyses that cannot include the relevant data, not the results of trials, and is therefore considered under the Assessment of reporting biases section (Kirkham 2010). We resolved any discrepancies through discussion or adjudication by a third author (SG or RB).

Measures of treatment effect

We used the Cochrane Collaboration statistical software, Review Manager 5.3, (RevMan 2014) to perform data analysis. We expressed dichotomous outcomes as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and continuous outcomes as mean differences (MDs) with 95% CIs if different trials used the same measurement instrument to measure the same outcome. Alternatively, we analysed continuous outcomes using the standardised mean difference (SMD) when trials measured the same outcome but employed different measurement instruments. To enhance interpretability of dichotomous outcomes, we calculated risk differences and number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) or the number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH).

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the participant. No trials included participants with bilateral shoulder pain.

Dealing with missing data

When required, we contacted trialists via email (twice, separated by three weeks) to retrieve missing information about trial design, outcome data, or attrition rates such as drop‐outs, losses to follow‐up and post‐randomisation exclusions in the included trials. For continuous outcomes with no standard deviation (SD) reported, we calculated SDs from standard errors (SEs), 95% CIs or P values. If no measures of variation were reported and SDs could not be calculated, we planned to impute SDs from other trials in the same meta‐analysis, using the median of the other SDs available (Ebrahim 2013). We have reported in the tables of Characteristics of included studies where outcome data were imputed.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity by determining whether the characteristics of participants, interventions, outcome measures and timing of outcome measurement were similar across trials. We assessed statistical heterogeneity using the Chi2 statistic and the I2 statistic (Higgins 2002). We interpreted the I2 statistic using the following as an approximate guide:

0% to 40% may not be important heterogeneity;

30% to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100% may represent considerable heterogeneity (Deeks 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

To assess small study effects, we planned to generate funnel plots for meta‐analyses including at least 10 trials of varying size. If asymmetry in the funnel plot was detected, we planned to review the characteristics of the trials to assess whether the asymmetry was likely due to publication bias or other factors such as methodological or clinical heterogeneity of the trials (Sterne 2011). To assess outcome reporting bias (non‐ or partial reporting of a pre‐specified outcome, which prevents the inclusion of data in a meta‐analysis), we compared the outcomes specified in trial protocols with the outcomes reported in the corresponding trial publications; if trial protocols were unavailable, we compared the outcomes reported in the methods and results sections of the trial publications (Dwan 2011; Kirkham 2010).

Data synthesis

For this review update, we identified a large number of trials, which studied a diverse range of interventions. To define the most clinically important questions to be answered in the review, after completing data extraction, one review author (MJP) sent the list of all possible trial comparisons to both of the original primary authors of this review (SG and RB). After reviewing the list of possible trial comparisons, both of these review authors discussed and drafted a list of clinically important review questions and categorised each trial comparison under the most appropriate review question. This process was conducted iteratively until all trial comparisons were allocated to a single review question, and was conducted without knowledge of the results of any outcomes. We defined the following review questions.

Is manual therapy and exercise (with or without electrotherapy) more effective than placebo, no intervention, or another active intervention (e.g. glucocorticoid injection, oral non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug (NSAID), arthroscopic subacromial decompression)?

Is manual therapy and exercise delivered in addition to another active intervention more effective than the other active intervention alone?

Is manual therapy alone more effective than placebo, no intervention, or another active intervention?

Is manual therapy delivered in addition to another active intervention more effective than the other active intervention alone?

Are supervised or home exercises alone more effective than placebo, no intervention, or another active intervention?

Are supervised or home exercises delivered in addition to another active intervention more effective than the other active intervention alone?

Is one type of manual therapy or exercise more effective than another (i.e. one type of manual therapy versus another type of manual therapy, or one type of exercise versus another type of exercise)?

We considered the first two to be the main questions of the review, as a multi‐modal intervention comprising manual therapy and exercise is most reflective of current clinical practice (Klintberg 2015; Kooijman 2013; Roberts 2014; Struyf 2012).

We planned to pool results of trials with similar characteristics (participants, interventions, outcome measures and timing of outcome measurement) to provide estimates of benefit and harm. We planned to synthesise effect estimates using a random‐effects meta‐analysis model based on the assumption that clinical and methodological heterogeneity was likely to exist and to have an impact on the results. Where we could not pool data, we presented effect estimates and 95% CIs of each trial in tables and summarised the results in the text.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not undertake any subgroup analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the robustness of the treatment effect (of main outcomes) to allocation concealment and participant blinding, by removing the trials that reported inadequate or unclear allocation concealment and lack of participant blinding from the meta‐analysis to see if this changed the overall treatment effect.

Summary of findings tables

We presented the results of the most important comparisons of the review in 'Summary of findings' tables, which summarise the quality of evidence, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined and the sum of available data on outcomes, as recommended by Cochrane (Schünemann 2011a). The 'Summary of findings' tables include an overall grading of the evidence related to each of the main outcomes, using the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation Working Group) approach (Schünemann 2011b).

In the Comments column of the 'Summary of findings' table, we report the absolute per cent difference, the relative per cent change from baseline and the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) (the NNTB is provided only when the outcome shows a statistically significant difference).

For dichotomous outcomes (global assessment of treatment success, adverse events), the absolute risk difference was calculated using the risk difference statistic in RevMan (RevMan 2014), and the result expressed as a percentage; the relative per cent change was calculated as the risk ratio ‐1 and was expressed as a percentage. For continuous outcomes (overall pain, function, pain on motion, quality of life), the absolute risk difference was calculated as the improvement in the intervention group minus the improvement in the control group, expressed in the original units (i.e. mean difference from RevMan divided by units in the original scale), expressed as a percentage. The relative per cent change is calculated as the absolute change (or mean difference) divided by the baseline mean of the control group, expressed as a percentage.

In addition to the absolute and relative magnitude of effect provided in the 'Summary of findings' table, for dichotomous outcomes we calculated the NNTB or the number needed to treat for an additional harmful effect (NNTH) from the control group event rate, and the risk ratio (RR) using the Visual Rx NNT calculator (Cates 2004). For continuous outcomes of function and overall pain, we calculated the NNTB using Wells calculator software, which is available at the Cochrane Musculoskeletal (CMS) editorial office (http://musculoskeletal.cochrane.org). We assumed a minimal clinically important difference (MCID) of 1.5 points on a 10‐point scale (or 15 points on a 100‐point scale) for pain (Hawker 2011), and 10 points on a 100‐point scale for function or disability (for example SPADI, Constant‐Murley, Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH)) (Angst 2011; Roy 2009; Roy 2010) for input into the calculator.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The search conducted up to March 2015 resulted in 3488 records across the four databases. Seven additional records were identified from screening reference lists of previously published systematic reviews and included trials. After removal of duplicates, we screened the titles and abstracts of 3166 unique records. We screened 339 full‐text articles and identified 60 trials (77 reports) which were included in the review (Ainsworth 2009; Al Dajah 2014; Atkinson 2008; Bae 2011; Bang 2000; Bansal 2011; Barbosa 2008; Barra 2011; Barra Lopez 2013; Baskurt 2011; Beaudreuil 2011; Bennell 2010; Bialoszewski 2011; Blume 2014; Brox 1993; Celik 2009; Citaker 2005; Clews 1987; Cloke 2008; Conroy 1998; Cook 2014; Dickens 2005; Djordjevic 2012; Engebretsen 2009; Ginn 2005; Giombini 2006; Haahr 2005; Haik 2014; Hay 2003; Heredia‐Rizo 2013; Holmgren 2012; Janse van Rensburg 2012; Kachingwe 2008; Kardouni 2014; Kassolik 2013; Kaya 2014; Kromer 2013; Littlewood 2014; Lombardi 2008; Ludewig 2003; Maenhout 2013; Martins 2012; Marzetti 2014; McClatchie 2009; Moosmayer 2014; Munday 2007; Osteras 2008; Rhon 2014; Senbursa 2007; Senbursa 2011; Struyf 2013; Subasi 2012; Surenkok 2009; Szczurko 2009; Teys 2008; Van den Dolder 2003; Walther 2004; Wang 2006; Winters 1997; Yiasemides 2011).

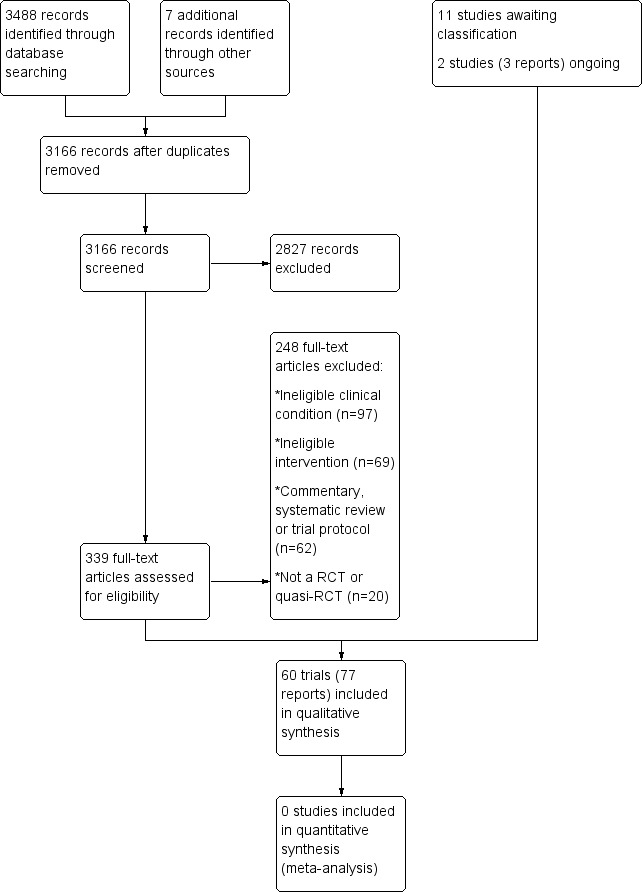

Eleven additional trials are awaiting classification. Six require translation (Acosta 2009; Bicer 2005; Just 2009; Leblebici 2007; Werner 2002; Wiener 2005) and five are only available as a conference abstract (Bube 2010; Ellegaard 2013; Ginn 2009; Pribicevic 2006; Wies 2008); see table of Characteristics of studies awaiting classification). Two ongoing trials (Roddy 2014; Van den Dolder 2010) were identified in clinical trials registries (see table of Characteristics of ongoing studies). A flow diagram of the study selection process is presented in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

A full description of all included trials is provided in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Design

All trials except one were described as RCTs (Kassolik 2013 used a quasi‐random method of allocation). All trials except two used a parallel‐group design (McClatchie 2009 and Teys 2008 used a cross‐over design). Forty‐eight trials included two intervention arms (Ainsworth 2009; Al Dajah 2014; Atkinson 2008; Bae 2011; Bang 2000; Bansal 2011; Barbosa 2008; Barra 2011; Baskurt 2011; Beaudreuil 2011; Bennell 2010; Bialoszewski 2011; Blume 2014; Celik 2009; Citaker 2005; Conroy 1998; Cook 2014; Dickens 2005; Djordjevic 2012; Engebretsen 2009; Haahr 2005; Haik 2014; Hay 2003; Heredia‐Rizo 2013; Holmgren 2012; Janse van Rensburg 2012; Kardouni 2014; Kassolik 2013; Kaya 2014; Kromer 2013; Littlewood 2014; Lombardi 2008; Ludewig 2003; Maenhout 2013; Martins 2012; Marzetti 2014; McClatchie 2009; Moosmayer 2014; Munday 2007; Osteras 2008; Rhon 2014; Senbursa 2007; Struyf 2013; Subasi 2012; Szczurko 2009; Van den Dolder 2003; Wang 2006; Yiasemides 2011), 10 included three arms (Barra Lopez 2013; Brox 1993; Clews 1987; Ginn 2005; Giombini 2006; Senbursa 2011; Surenkok 2009; Teys 2008; Walther 2004; Winters 1997) and two included four arms (Cloke 2008; Kachingwe 2008).

Participants

A total of 3620 participants were included in the 60 trials, and the number of participants per trial ranged from nine to 207. The median of the mean age of participants was 51 (interquartile range (IQR) 46 to 56) years, and the median of the mean duration of symptoms was 11 (IQR 5.5 to 25) months. Fifty‐two per cent of the participants were women.

Diagnostic labels used by trialists included subacromial impingement syndrome (n = 36: Al Dajah 2014; Bae 2011; Bang 2000; Barra 2011; Barra Lopez 2013; Baskurt 2011; Beaudreuil 2011; Blume 2014; Brox 1993; Celik 2009; Citaker 2005; Conroy 1998; Cook 2014; Dickens 2005; Djordjevic 2012; Engebretsen 2009; Haahr 2005; Haik 2014; Heredia‐Rizo 2013; Holmgren 2012; Janse van Rensburg 2012; Kachingwe 2008; Kardouni 2014; Kaya 2014; Kromer 2013; Lombardi 2008; Ludewig 2003; Maenhout 2013; Martins 2012; Munday 2007; Osteras 2008; Rhon 2014; Senbursa 2007; Struyf 2013; Subasi 2012; Walther 2004), rotator cuff tendinitis (n = 4: Atkinson 2008; Clews 1987; Littlewood 2014; Szczurko 2009), supraspinatus tendinitis (n = 3: Bansal 2011; Barbosa 2008; Giombini 2006), painful arc (n = 2: Cloke 2008; McClatchie 2009), rotator cuff tear (n = 2: Ainsworth 2009; Moosmayer 2014), chronic rotator cuff disease (n = 1: Bennell 2010), chronic rotator cuff injury (n = 1:Bialoszewski 2011) or a mixture of labels (i.e. some participants with impingement, others with tendinitis) (n = 3: Senbursa 2011; Surenkok 2009; Van den Dolder 2003). However, there were inconsistencies in the diagnostic criteria for (or definitions of) each of the conditions (see Characteristics of included studies).

Six (10%) trials (Ginn 2005; Kassolik 2013; Teys 2008; Wang 2006; Winters 1997; Yiasemides 2011) included participants with non‐specific shoulder pain that was compatible with a diagnosis of rotator cuff disease. Two trials (Hay 2003; Surenkok 2009) included patients with either rotator cuff disease or adhesive capsulitis, but participants with the latter condition comprised less than 25% of the sample.

Trials were conducted in USA (n = 9), Turkey (n = 8), UK (n = 7), Australia (n = 6), Brazil, Norway (n = 4 each), Spain (n = 3), Belgium, Canada, Italy, Poland, The Netherlands (n = 2 each), Denmark, France, Germany, India, Republic of Korea, Saudi Arabia, Serbia, South Africa and Sweden (n = 1 each).

Interventions and Comparisons

A detailed description of the interventions delivered in each trial is summarised in the Characteristics of included studies and a summary of the intervention components across trials is presented in Table 4. The median duration of the physical therapy interventions was six weeks (range one to 24), with a median of two treatment sessions delivered per week (range one to seven). The types of manual therapy and exercise delivered were very heterogeneous across the trials.

1. Characteristics of manual therapy and exercise interventions.

| Study ID | Manual therapy component(s) | Exercise component(s) | Duration of session (minutes) | Number of sessions per week | Number of weeks treatment |

| Ainsworth 2009 | None | The participant was taught to start with a flexed elbow and to raise the arm to a vertical position. The participant was then taught to control the arm with sways in a 20‐degree arc before elevating and lowering the arm using a weight of approximately 0.75 kg. When the participant could carry out these activities supine, the head of the treatment couch was gradually inclined until they were able to perform the exercises in a sitting position. The participants also carried out stretching exercises to improve ranges of elevation, internal and external rotation, resistance band exercises into internal and external rotation, activities to improve proprioception, posture correction and adaptation of functional activities | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported (assumed to be 6 weeks) |

| Al Dajah 2014 | Soft tissue mobilisation for the subscapularis for 7 minutes and 5 repetitions of the contract‐relax proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) technique for the shoulder internal rotator muscles followed by 5 repetitions of a PNF‐facilitated abduction and external rotation diagonal pattern | None | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| Atkinson 2008 | Manipulation (high velocity, low‐amplitude, gentle‐impulse, shoulder adjustive thrust based on extensive motion palpation) | None | Not reported | 3 | 2 |

| Bae 2011 | None | Motor control and strengthening exercises | 30 | 3 | 4 |

| Bang 2000 | Passive accessory or passive physiological joint mobilisation Maitland grades I‐V; soft tissue massage and muscle stretching | Home exercises: simple cervical and thoracic postural exercises such as chin tucks, and self‐mobilisation such as caudal glides of the glenohumeral joint | 30 | 2 | 3 |

| Bansal 2011 | Deep friction massage to supraspinatus tendon in a transverse direction | Codman's exercises consisting of pendulum or swinging motion of the arm in flexion, extension, horizontal abduction, adduction and circumduction. Intensity (arc of motion) was increased as tolerated | 10 | 7 | 10 days |

| Barbosa 2008 | Front, back, lower longitudinal and lateral relaxations of the glenohumeral joint, anteroposterior movements of the acromioclavicular (squeeze) joint and anteroposterior, inferior‐superior and superior‐ inferior movements of the sternoclavicular joint | Eccentric training exercises: the 'empty the can' movement (the participant performs abduction movements of the shoulder in the scapular plane, with medial rotation) when treating the supraspinatus muscle, or the 'right curl' movement (the participant flexes his elbow, with the arm abducted beside the body) when treating biceps brachii dysfunctions. Movement resistance was offered manually, always by the same researcher and respecting the participant's pain limit | Not reported | 3 | 4 |

| Barra 2011 | Diacutaneous fibrolysis: application of a metallic hook as deeply as possible following the intermuscular septum between the muscles of the cervico‐scapular and shoulder region in a centripetal direction towards the pain location | None | 15 | 1 | 1 |

| Barra Lopez 2013 | Diacutaneous fibrolysis: application of a metallic hook as deeply as possible following the intermuscular septum between the muscles of the cervico‐scapular and shoulder region in a centripetal direction towards the pain location | No details provided | Not reported | 2 | 3 |

| Baskurt 2011 | None | Intervention group: scapular proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) exercises, scapular clock exercise, standing weight shift, double arm balancing, scapular depression, wall push up, wall slide exercises, strengthening and stretching exercises Control group: strengthening and stretching exercises |

Not reported | 3 | 6 |

| Beaudreuil 2011 | Passive mobilisation of the shoulder with a painless ROM | Dynamic humeral centring: learning the lowering of the humeral head during passive abduction of the shoulder, and actively lowering the humeral head by co‐contraction of the pectoralis major and latissimus dorsi during active abduction of the shoulder. Home exercise: no details provided |

Not reported | 3 x wk 1‐3; 2 x wk 4‐6 | 6 |

| Bennell 2010 | Soft tissue massage, glenohumeral joint mobilisation, thoracic spine mobilisation, cervical spine mobilisation, scapular retraining, postural taping | Most exercises required the participant to incorporate their scapular retraining with strengthening of the rotator cuff muscles. Some exercises reinforced and facilitated correct posture. Resistance for specific exercises was provided by hand weights or elastic theraband. Exercises were taught and performed during each treatment session and were otherwise self‐administered at home | 30 to 45 | 2 x wk 1‐2; 1 x wk 3‐6; fortnightly wk 7‐10 | 10 |

| Biasoszewski 2011 | Mobilisation of the glenohumeral joint and soft tissues using Kaltenborn's roll‐glide techniques, Cyriax deep transverse massage, Mulligan's mobilisation with movement and typical techniques of joint mobilisation in the anteroposterior direction | Standard passive and active exercises used to improve the ROM and restore muscle strength. The rotator cuff was initially strengthened in the painless ROM by performing active, passive and self‐assisted exercises. Once the full ROM has been achieved, strengthening exercises were applied, ranging from flexion, abduction and external rotation to internal rotation adduction and extension | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Blume 2014 | None | Supervised exercises: eccentric or concentric exercises included the seated 'full can', sidelying internal rotation (IR), sidelying external rotation (ER) with towel roll, supine protraction, sidelying horizontal abduction, sidelying abduction, and prone shoulder extension. All exercises were performed using a dumbbell for resistance. Home exercises: stretching and postural correction exercises |

60 | 2 | 8 |

| Brox 1993 | None | Supervised exercises: ROM and strengthening exercises | 60 | 2 | 24 |

| Celik 2009b | None | Intervention group: supervised shoulder flexion below 90 degrees, abduction, T‐bar (wand) exercises containing internal‐external rotation and extension, posterior capsule stretching and internal rotation exercises and rotator cuff strengthening exercises Control group: supervised shoulder flexion exercises above 90 degrees, posterior and inferior capsule stretching exercises, rotator cuff strengthening and internal rotation exercises |

Not reported | 7 | 2 |

| Citaker 2005 | Manual mobilisation (details not provided) | Theraband exercises permitting concentric and eccentric strengthening of the shoulder muscles. The exercises began with the elbow flexed 90 degrees and the shoulder in the neutral position. The exercises were performed through an arc of 45 degrees in each of the 5 planes of motion. In addition, Codman pendulum exercises were utilised as a home programme | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Clews 1987 | Massage of the long head of biceps, biceps tendon, pectorals, supraspinatus and infraspinatus | None | 15 | 3 | 1 |

| Cloke 2008 | Manual therapy (details not provided) | Exercises (details not provided) | Not reported | 6 sessions over 18 weeks | 18 |

| Conroy 1998 | Mobilisation: depending on the direction of restriction in capsular extensibility, inferior glide, posterior glide, anterior glide or long axis traction could be applied to the participant with oscillatory pressure. Stretch could also be applied in the case of muscle spasm. |

|

15 | 3 | 3 |

| Cook 2014 | Grade III posterior‐anterior mobilisations to the neck | Self‐ and externally‐applied stretching, isotonic strengthening, and restoration of normative movement | Not reported | Varied per participant | Mean of 8 (varied per participant) |

| Dickens 2005 | Acromioclavicular joint, thoracic, cervical spine and glenohumeral joint mobilisation. The physiotherapist assessed the range of accessory movement available in each participant's glenohumeral (anteroposterior, longitudinal caudad), acromioclavicular (anteroposterior, longitudinal caudad), cervical (posterior–anterior) and thoracic spine joints (posterior–anterior and transverse) with passive accessory movements. Any joints that were found to have restricted movement were addressed with mobilisations into the direction of resistance and pain to help restore full pain‐free range of movement | Exercises for the recruitment and strength of scapulothoracic muscles (especially lower trapezius and serratus anterior). The exercise programme was progressed to involve strengthening of infraspinatus, subscapularis and teres minor relative to the supraspinatus and deltoid. The rotator cuff exercises were done with the use of resistance and participants were given Theraband for home use. The exercises started in neutral positions with isometric contractions and were progressed to inner range, through range, outer range and into functional positions. The resistance and speed of these exercises were altered and progressed | Dependent on participant | Not reported | Not reported |

| Djordjevic 2012 | Mobilisation with movement (MWM): during the MWM treatment, the participant was seated, and the therapist was positioned on the opposite side of participant's painful shoulder. The therapist applied the thenar of one hand on the anterior aspect of the participant's humeral head and the other hand on his/her scapula. The hand on the humeral head performed a posterolateral glide, while the other hand stabilised the scapula. During this manoeuvre, the participant was encouraged to perform active shoulder movement to the point of the first onset of pain | Pendulum exercises and pain‐limited, active ROM exercises of shoulder elevation, depression, flexion, abduction, rotations, and strengthening exercises. Strengthening exercises were isometric in nature, working on the external shoulder rotators, internal rotators, biceps, deltoid, and scapular stabilizers (rhomboids, trapezius, serratus anterior, latissimus dorsi, and pectoralis major) | Not reported | 7 | 10 days |

| Engebretsen 2009 | None | Supervised exercises: the initial aim was to unload the stress on the rotator cuff and subacromial structures. During this phase, a mirror for awareness of posture, an elastic rubber band and a sling fixed to the ceiling were used. The participants received immediate feedback and correction (supervision) by the physiotherapist. Once dysfunctional neuromuscular patterns were normalised, endurance exercises were performed with gradually increasing resistance. Participants had an adjusted programme at home, which consisted of correction of alignment during daily living and simple low loaded exercises with a thin elastic cord to provide assistance and resistance to the movement | 45 | 2 | 12 |

| Ginn 2005 | Passive joint mobilisation at the sternoclavicular and acromioclavicular joints | ROM exercises: exercises were upgraded from active assisted to active to resisted active exercises using free weights or elastic resistance | Not reported | 2 | 5 |

| Giombini 2006 | None | Supervised and home exercises, consisting of pendular swinging in the prone position in flexion and extension of the shoulder and passive glenohumeral stretching exercises to tolerance | Not reported | 1 | 4 |

| Haahr 2005 | Soft tissue treatments (details not provided) | Supervised exercises: active training of the periscapular muscles (rhomboid, serratus, trapezoid, levator scapulae, pectoralis minor muscles) and strengthening of the stabilising muscles of the shoulder joint (rotator cuff). This was done within the limits of pain | 60 | 3 x wk 1‐2; 2 x wk 3‐5; 1 x wk 6‐12; 2‐3 x wk 13‐19 | 12 |

| Haik 2014 | Low‐amplitude, high velocity thrust thoracic spine manipulation | None | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Hay 2003 | Active and passive mobilisation | Home exercise programme | 20 | 1 to 2 | 6 |

| Heredia‐Rizo 2013 | Manual therapy based on soft tissue techniques: micro‐mobilisations of the cervical structures in all movement axes, relaxation manoeuvres performed to fascial restrictions involving the cervical and scapulohumeral region, and a repositioning of the head of the humerus as recommended by Kaltenborn | Supervised exercises: pendular movements using 1 kg of weight in prone, assisted active movements with a pulley, and proprioceptive exercises with a ball in the horizontal plane | 40 | 5 | 3 |

| Holmgren 2012 | None | Supervised exercises: two eccentric exercises for the rotator cuff (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor), three concentric/eccentric exercises for the scapula stabilisers (middle and lower trapezius, rhomboideus, and serratus anterior), and a posterior shoulder stretch | 30 | 1 x wk 1‐2; fortnightly wk 3‐12 | 12 |

| Janse van Rensburg 2012 | Thoracic spinal manipulation: a specific high velocity low amplitude "extension with rotation" thrust manipulation was applied to the shoulder | Exercises to stimulate the lower fibres of trapezius and specific rotator cuff‐strengthening | 30 | 1 | 6 |

| Kachingwe 2008 | Intervention group: glenohumeral joint mobilisation was administered based on assessment of glenohumeral joint anterior, posterior and inferior glides and long‐axis distraction passive accessory motions using a 0‐6 accessory motion scale. For situations where there was reactivity within the capsular ROM, grade I‐II mobilisation were applied. For situations where there was no reactivity but capsular hypomobility, grade III‐IV accessory motions were applied. Control group: glenohumeral joint mobilisation with movement (Mulligan technique) involved the therapist applying a sustained posterior accessory glide to the glenohumeral joint while the subject simultaneously actively flexed the shoulder to the pain‐free endpoint and applied a gentle overpressure force using the contralateral arm |

Supervised exercises including posterior capsule stretching, postural correction exercises, and an exercise programme focusing on rotator cuff strengthening and scapular stabilisation. Participants were instructed to perform a home exercise programme mimicking the exercises performed in the clinic | Not reported | 1 | 6 |

| Kardouni 2014 | Thoracic spinal manipulation: a high velocity, low amplitude thrust applied to the lower thoracic spine, mid thoracic spine, and cervicothoracic junction | None | Not reported | 1 | 1 |

| Kassolik 2013 | Classic massage of the shoulder girdle and glenohumeral joint was performed in a side recumbent position. During the massage, typical classic massage techniques (Swedish) were used ‐ stroking with the palms (effleurage), friction with the palms, kneading (petrissage), percussion (tapottement), and vibration | None | Not reported | 5 | 2 |

| Kaya 2014 | Scapular mobilisation (superoinferior gliding, rotations, and distractions to the scapula), neuromuscular facilitation techniques for scapula motions at anterior elevation–posterior depression and posterior elevation–anterior depression planes, glenohumeral joint mobilisation with long axis traction and posterior or inferior glide techniques to improve shoulder internal rotation limitations, and soft tissue massage and joint mobilisation of the neck, thoracic region, and elbow areas | Supervised and home exercises, including strengthening, flexibility (ROM) and Codman's pendulum exercises | 90 | 1 | 6 |

| Kromer 2013 | Painful and angular and/or translatory restricted peripheral joints were treated with manual glide techniques according to the concept of Kaltenborn. Comparable signs of the spine segments were treated with posterior‐anterior glides or coupled movements. Shortened muscles were stretched according to the description of Evjenth & Hamberg. Neural tissue was treated according to Butler | Core exercise programme ‐ dynamic exercises started with 2 sets of 10 repetitions and with low resistance (yellow rubber band); shoulder and neck stretches were held for 10 seconds and repeated twice; isometric scapular training positions were held for 10 seconds and repeated twice | 20 to 30 | 2 x wk 1‐5; 3 x wk 6‐12 | 12 |

| Littlewood 2014 | Manual therapy or massage (no details provided) | Self‐managed loaded exercise: involved exercising the affected shoulder against gravity, a resistive therapeutic band or hand weight over 3 sets of 10 to 15 repetitions completed twice per day. The exercise was prescribed and operationalised within a self‐managed framework which included focus upon knowledge translation, exercise/skill‐acquisition, self‐monitoring, goal‐setting, problem‐solving and pro‐active follow‐up. | Not reported | 1 | 8 |

| Lombardi 2008 | None | Progressive resistance training programme. The exercises were flexion, extension, medial rotation and lateral rotation of the shoulder | Not reported | 2 | 8 |

| Ludewig 2003 | None | Home exercise programme involving: two stretches (pectoralis minor stretch and posterior shoulder stretch), a muscle relaxation exercise for the upper trapezius performed in front of a mirror, and progressive resistance strengthening exercises for two muscle groups (serratus anterior muscle and humeral external rotation) | Not reported | 7 | 10 |

| Maenhout 2012 | None | Eccentric exercise consisted of full can (thumb up) abduction in the scapular plane, which was performed with a dumbbell weight | Not reported | 7 | 12 |

| Martins 2012 | None | Intervention group only: proprioception exercises: exercises with joint position, rhythmic stabilisation and repositioning of the members, unstable base, proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation, and speed and accuracy Both groups: pendulum exercises of the shoulder, stretching of the cervical spine and shoulder muscles, exercises with a stick (to maintain or improve ROM), exercises to strengthen the muscles of the rotator cuff and scapular stabilisers |

Not reported | 2 | 6 |

| Marzetti 2014 | None | Supervised exercises: neurocognitive exercises (intervention group) or strengthening exercises focused on the rotator cuff and scapular stabilising muscles, stretching exercises, Codman's pendulum exercises and exercises against elastic band resistance (control group) | 60 | 3 | 5 |

| McClatchie 2009 | Lateral cervical glide mobilisations: the lateral aspect of the spinous processes of C5, C6, and C7 was landmarked on the ipsilateral side of the patient's painful shoulder. The examiner's thumb remained on the lateral aspect of the spinous process of C5, with the opposite hand placed on the patient's non‐affected shoulder or head for counterbalance as a lateral movement toward the non‐painful side was applied with the mobilising hand | None | Not reported | 1 | 1 |

| Moosmayer 2014 | None | Supervised exercises only, with particular attention directed towards correction of upper quarter posture and restoration of scapulothoracic and glenohumeral muscular control and stability. Local glenohumeral control was addressed by exercises to centre the humeral head in the glenoid fossa. Isometric exercises and exercises against eccentric and concentric resistance for shoulder rotators were given. When local glenohumeral control was achieved, exercises were given with increasing loads and progressed from neutral to more challenging positions | 40 | 2 x wk 1‐12; > 2 x wk 12‐24 | 24 |

| Munday 2007 | Shoulder girdle adjustments: high‐velocity, low‐amplitude manipulation in the direction of restricted end feel or joint play was performed. Participants sat in a comfortable position with the shoulder girdle exposed. Adjustments to the acromioclavicular joint were most common, although adjustments to the ribs, scapula and glenohumeral joints were made as well. The spine was not adjusted in this trial | None | None | 3 | 3 |

| Osteras 2008 | None | Supervised progressive resistance exercise therapy, comprising global aerobic exercises using a stationary bike, a treadmill, or a step machine, and semiglobal and local exercises using such medical exercise therapy equipment as wall pulley apparatus, lateral pulley apparatus, inclines board, angle bench, multiple purpose bench, shoulder rotator, dumbbells or barbells | 40 | 3 | 12 |