Abstract

As the United States population ages, managing pathologies that largely affect older adults, including sarcopenia (i.e., loss of muscle mass and strength) represents a significant and growing clinical challenge. In addition to increased rates of sarcopenia with age, its incidence and impact increase after acute illness, increasing the risk of functional decline, institutionalization, or death. Resistance-based exercises promote muscle regeneration and strength and are an advised therapy for such patients. Yet, such therapeutic exercises are normally conducted either under direct clinical oversight or unsupervised by patients at home, where compliance rates are low. The presented device, BandPass, aims to create an integrated force data detection and acquisition system for monitoring and transmitting at-home exercise force data to patients and clinicians. A potentiometer-based sensor was integrated to a resistance exercise band through the use of custom designed electronics, which incorporated Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) for wireless transmission to a mobile ‘app’. A protocol for calibrating the device was developed using a range of loads and validated in static benchtop and dynamic testing. Data from a pilot study with 7 older adults was also collected and analyzed to test the device. BandPass is 94% accurate with a coefficient of variation (CoV) of 4.9% and sensitivity of 150g. The pilot study recorded 147 exercises, allowing for analysis on patients’ exercise performances. BandPass was successfully able to measure force continuously over time during exercises, measure longitudinal compliance with exercises, and quantify force continuously over time. A mobile health (mHealth) force-sensing system allows for the remote monitoring of prescribed in-home resistance exercise band programs for at-risk older adults, bridging the gap between clinicians and patients.

Keywords: Medical device, mHealth, biomedical engineering, force measurement, remote medical sensing, sarcopenia, resistance-based training

I. Introduction

Older adults account for 17% of the United States population [1] and are at risk of developing age-related co-morbidities. Sarcopenia, the age-related loss of muscle mass and function [2], impacts ~15% of older adults [3], ~30% of older adults with chronic diseases [4], and 76% of hospitalized seniors [5,6], with rates exceeding 60% over age 80 [7]. The risk of developing sarcopenia increases following an acute illness or hospitalization. Sarcopenia threatens a person’s independence and is associated with increased risk of disability, morbidity, and mortality [7].

Resistance exercises are a key component to treating sarcopenia, as they can mitigate the trajectory of muscle loss and promote muscle regeneration [8]. Such modalities are often initiated by ambulatory clinician-referrals, during an inpatient stay, or upon hospital discharge to office or home settings by a physical therapist or an exercise physiologist [9]. Task forces have endorsed progressive resistance-based training [10,11] that produce skeletal muscle contractions by using elastic therapy bands, dumbbells, and body weight, all of which can lead to muscle hypertrophy, improved strength, and improved physical performance [12]. Treatment strategies are function- and outcome-based, incorporating elements of intensity, volume, and progression [13]. Given the efficacy of longitudinal engagement in progressive resistance exercise training for improving physical function in high-risk, older adults, it is critical for clinicians to understand if and which exercise is completed, the extent that an exercise is completed, and how the completion of the exercise may change over time [7].

Evidence-based resistance exercises using bands rely on in-person or group-based interactions, where activation and motivation enhance engagement, compliance, accountability, and adherence to ensure proper use [14]. As the value of clinician monitoring in providing patient feedback is predominantly dependent on in-person sessions [15], conducting therapy in the home-based setting may impact treatment or outcomes [16]. Older adults have low adherence to physical activity programs [14], with non-compliance rates and lack of participation approaching 40%, in part due to cost, transportation, and lack of social support [17]. Current at-home regimens rely on self-report diaries or verbal reports that may be inaccurate and subject to recall bias [18]. Therefore, a clinician’s ability to quantitatively assess at-home compliance remains unreliable and challenging.

Remote medical sensing or mobile health (mHealth) systems that measure, track, analyze, and provide patient-oriented feedback may overcome these limitations and enhance exercise regimen engagement [19]. As older adults’ use of technology grows (in 2019, Internet use was >70%, smartphone use >53%), using mHealth systems can feasibly and practically be considered for use in clinical care [20]. Devices providing automated health behavior change data through remote monitoring improve adherence [19, 21] by potentially overcoming the limits of interventions relying heavily on self-motivation [22] and limitations associated with face-to-face clinical interactions [23]. Routine integration of systems into therapeutic programs can partially substitute in-person oversight, not only to lower costs, but also to overcome transportation and geographic care barriers to access services [24].

Research and commercial products for monitoring physical activity utilize information input by the user such as perceived exertion, steps, or heart rate [25]. There are no clear options to automatically track upper body muscle strength longitudinally. Existing work on monitoring physical strength has been conducted in the context of sports medicine for optimizing athlete function and recovery [26]. Because of this gap, clinicians and patients are unable to quantify progress through home-based resistance exercises. As there is no reliable way to quantify the progression of physical therapy in older adults, research and development of monitoring strategies can be immediately impactful. An at-home device that monitors and transmits exercise data to the user and clinician represents a potential solution to this clinical challenge.

Our proposed solution, BandPass, is a remote-sensing Bluetooth Low Energy-enabled (BLE) resistance exercise band system that provides clinically relevant data on compliance and use of exercise training with feedback that can be personalized. The components of this device (patent WO 2019/222630 A1) consist of a potentiometer sensor; microcontroller with BLE capabilities; circuit housing and elastic exercise band; and mobile ‘app’ designed to capture data. In short, this paper presents a system that captures quantitative, accurate, repeatable measures of muscle strength data that will be transmitted to a cloud-based data processing platform, enabling synchronous and asynchronous feedback to patients and clinicians.

II. System Design

A. Mechanical and Electrical Hardware

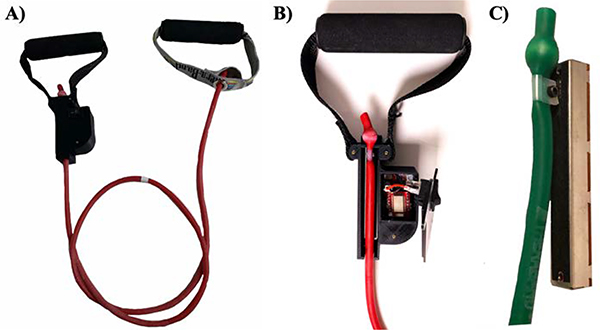

BandPass integrates a potentiometer-based sensor with an elastic exercise band through the use of custom- designed electronics for control and wireless transmission using human-centered design approaches to develop a small form-factor handle. The hardware consists of two handles at either end of a resistance exercise band (Fig. 1a), with a displacement sensing assembly positioned at one end (Fig. 1b). The sensor is a Bourns (PTA4543–2010CPB) 60mm (45mm travel), 10kΩ linear potentiometer that is connected linearly to the tubing, limiting potential multi-axial loads to a single dimension. When the band is displaced during exercise, the potentiometer’s wiper is also displaced, resulting in a change of resistance and thereby voltage. This voltage change is mapped to a correlated force in kilograms; this mapping is defined by calibrating the device with a set of known loads and fitting a regression equation.

Fig. 1.

Depiction of hardware components: A) BandPass overview B) close up of prototype device which consists of a band adhered to a linear potentiometer, a custom printed circuit board, a BLE System-on-Chip integrated circuit, a power switch, a custom 3D printed casing, and handle; C) mechanism in which band is adhered to potentiometer.

A novelty in the design lies in the integration mechanism between the elastic band and the potentiometer. The potentiometer’s wiper is modified with a quasi-circular cut that allows for the wiper to be positioned around a 4–40 screw that passes through a customized nylon cable clamp (Fig. 1c). The wiper is clamped 9mm from the bottom of the retention ball inside the band. This serves as a repeatable reference point between BandPass assemblies and ensures that the sensor can measure 400% elongation of the band. The potentiometer was measured to be linear over a travel range of 36mm, hence equates to 400% elongation.

A custom housing was designed to secure the linear potentiometer, a 26mm x37mm x18mm printed circuit board (PCB) and accompanying electronics. The case, which is 3D printed from Nylon PA12, securely aligns the sensor with the resistance band and limits handle rotation, thereby constraining the forces to one dimension and improving the device’s accuracy and repeatability. A large rocker switch is ergonomically positioned on the front face of the case for easy use and a micro-USB port is exposed on the side of the case for charging the device. With all elements of the system concealed, BandPass does not interfere with the user experience (Fig. 1).

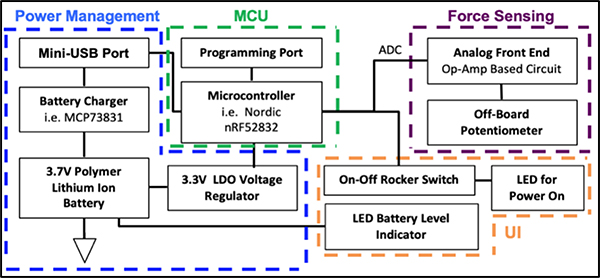

An overview of the electrical design is seen in figure 2. The circuit senses the resistance of the 10kΩ linear potentiometer connected to the elastic band that is displaced during exercise, which results in a voltage change that is mapped to a correlated force in kg. In lieu of using a separate MCU PCB, the integrated PCB includes a BLE System-on-Chip IC (Nordic nRF52832); an on-board antenna; a micro-USB charger and a rechargeable lithium-ion battery; an on-off switch; and the potentiometer’s supporting analog circuitry. The circuit operates at 3.7V, records sensor data on the MCU in binary using the on-chip 12-bit ADC, samples the data at 10Hz and transmits data via BLE to a paired mobile device.

Fig. 2.

BandPass circuit block diagram- Main electrical processes: power management block captures USB charging of device and connected to MCU; ADC signal from microcontroller is sent to force sensing circuit; user interface (UI) includes a switch and LEDs for power/battery verification.

The potentiometer’s circuitry consists of an AD 8609 rail-rail operational amplifier in negative feedback. A unity gain buffer is used to isolate the input of the potentiometer and decrease any disturbances in the system. Overall, the potentiometer’s circuit draws a very low current of 0.33mA. The 85mAh rechargeable lithium-ion coin battery has a charging voltage of 4.2 ±0.03V, a charging current of 0.5A and a charging time of 3 hours. The average battery life of the design is 6 hours, which is an appropriate amount of battery life for the targeted user as it would account for 6-hour long training sessions.

B. Mobile Application and Data Acquisition

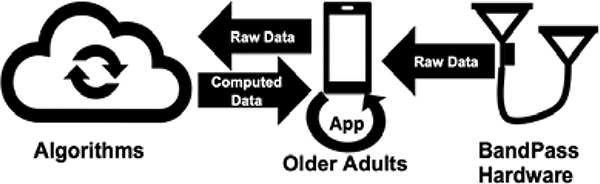

An Android prototype ‘app’ was created through an iterative user-centered design process that included 16 older adults through three rounds of development. The development has been previously described by Petersen et al. [27]. In brief, this app was designed to receive BandPass data and transmit to a cloud-based service. Figure 3 shows the data flow for the BandPass system.

Fig. 3.

Data Pipeline and Flow

The app displays basic exercise information, allowing the user to select an exercise, begin recording data, and display past recordings. The app consists of exercise demonstrations, selection, and completion; Borg perceived effort scale [28]; and previous data summary (per exercise mean number of repetitions, perceived effort, duration, total number of exercises performed). This platform therefore allows for remote clinical monitoring of patient compliance and progress to prescribed in-home exercise programs, providing insight into a patient’s recovery trajectory.

C. Device Calibration

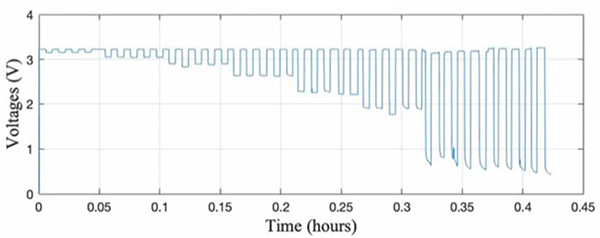

A calibration protocol using hanging weights was developed for BandPass. The handle with the sensor was secured to a high bench top, with the other end of the band connected to loaded weights. Known weights ranging from 0.6kg to 4.6kg (increasing by 0.45kg) were loaded and unloaded in 45 second increments. The corresponding voltages (captured on an oscilloscope) were logged and plotted against time (Fig. 4). As shown, there is negligible noise in the data despite some nonlinearity when loading and unloading the weights, suggesting that the overall design can discern noise and only measures forces that are aligned with the potentiometer, as intended. Furthermore, the consistent return to 3.3V after each load indicates that the potentiometer’s wiper returns to its initial position after each run with no slippage.

Fig. 4.

BandPass calibration data

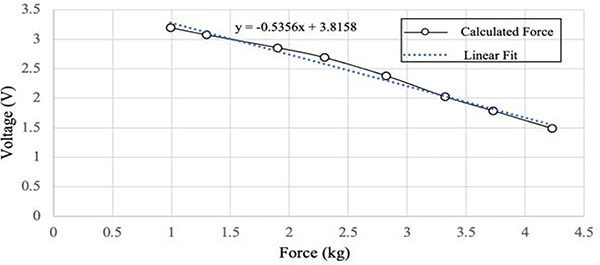

To streamline the calibration process, the potential was recorded on the MCU in binary using the on-chip 12-bit ADC and input to a MATLAB script that converts the data to a 255 scale and then calculates the demeaned voltages. The MATLAB function finds the data points that fall between the median of the demeaned voltages <0 ± a threshold of 0.025, which is 1.5% from the median. The average of the local flat region is then stored for each load. The applied forces were then recorded against their corresponding voltages and a regression line was fitted (Fig. 5). This results in a device specific calibration equation that is a first-order linear fit between the ADC data and load. The general formula is calculated as . Each BandPass device is conditioned individually, and calibration is done in a stepwise fashion. Loads are applied in increments of 450g with 45s of data acquisition for each load, up to a maximum load of 4.6kg.

Fig. 5.

BandPass calibration curve example relating force and voltage

III. Experimental Methods

A. Static Benchtop Testing

The calibrated device’s accuracy was evaluated using test loads (not used for calibration) and compared with BandPass’s computed force. The differences and errors between the computed and true forces were calculated. Precision was calculated by repeatedly applying the same load to the device and calculating the coefficient of variation (CoV). It is important to note that a general calibration method was tested, where a common calibration equation is used between bands of the same color, instead of being device specific. However, this method lacked accuracy, as each potentiometer has a tolerance of 20% and there is ~5% variation in the placement of the potentiometer’s wiper to the band. Device sensitivity, which defines the minimum detectable change in load, was also tested and found to be 150g. The system’s response to varying force inputs was tested by randomly applying the loads in a non-incremental fashion. This is a critical test, as the exerted force during the same or different exercises can vary non-linearly.

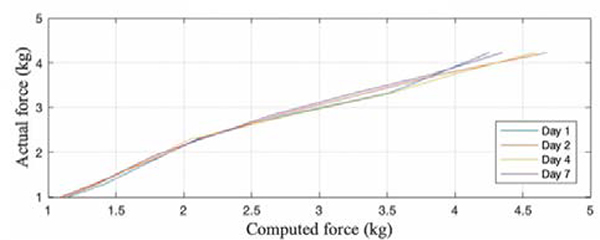

To test the device’s repeatability, a critical functional capability for the band’s long-term performance, the same weights used to calibrate the band were tested after 1, 2, 4 and 7 days of continuous use. CoV between the computed and true loads was calculated and the regression equation was compared for the band’s initial calibration and post use.

B. Dynamic Testing

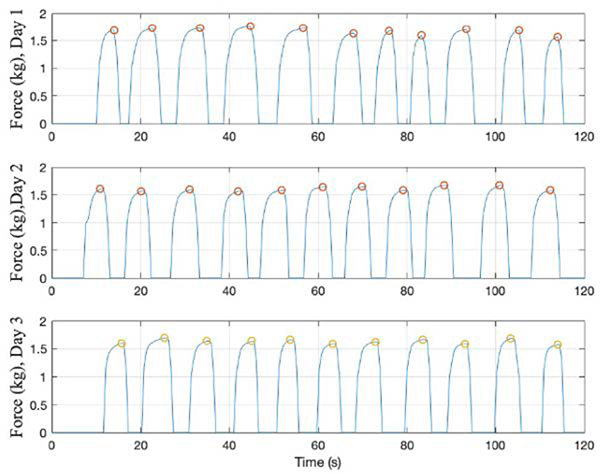

In order to demonstrate BandPass’s ability to capture a user’s force during exercise, three different controlled exercises (T-lift, bicep curl and seated row) were performed by a single user and repeated over multiple days. A controlled T-lift exercise was tested, where the middle of the band and a location on the floor were marked. A bar was clamped to the top of a bench (at shoulder height) to act as the reference point that the user would bring their arm up to for every repetition. To perform the T-lift, the user stands with both feet on the center of the band holding both handles at their sides with palms facing in. The handle with the sensor is held in the user’s right hand. The user then lifts both arms out to shoulder height, forming a “T” where arms are parallel to the ground and the user’s hand touches the bar. The position is held for 3 to 5 seconds. The user then slowly lowers their arms back to their sides and repeats the exercise for 11 repetitions. This test was repeated over 3 days and data was collected and compared.

Bicep curls and seated rows were also tested. For the bicep curl, the user places their right foot on the center of the band, holding both handles, palms facing upward (sensor in the right hand). Starting with their arms resting by their sides, the user then pulls the band upward, bending at the elbow, until the palms nearly touch their shoulders. For the seated row, the band is wrapped around a post at a marked position that is at mid-chest height. The user holds both handles (sensor in the right hand) with palms turned in. Starting with their arms straight, the user then pulls the band towards their abdomen, bending at the elbows, until the upper arms are slightly behind the torso. Arms are then slowly extended back to the starting position.

C. Patient Study

Seven adults aged ≥65 years were recruited through a primary care clinic at Dartmouth-Hitchcock in Lebanon, New Hampshire and approved by the Dartmouth Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects and the Institutional Review Board. Participants received a BandPass (which is classified as a Class II, 510(k) exempt medical device), a Samsung Galaxy Tab A with the application installed and instructions on how to use both. They were shown how to complete four exercises (T-lift, bicep curl, seated row and triceps extension) and asked to perform the exercises once a week for the month-long study. Force exerted during each exercise, duration of each exercise, when each exercise was performed, and the Borg scale of perceived exertion per exercise were collected through BandPass and analyzed for each participant. We calculated the mean, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation of force and repetitions (occurrences of force above a threshold) for each exercise by type. Along with the mean duration of each exercise by type.

IV. Results

A. Static Benchtop Testing

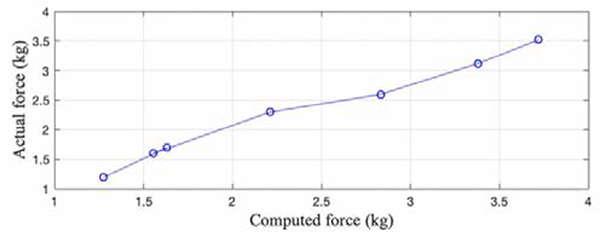

The average accuracy for the BandPass device was found to be 94%. Figure 6 demonstrates the system’s capability of computing random loads. BandPass’s precision had a CoV of 4.9% and an overall sensitivity of 150g. Figure 7 shows the system’s repeatability from day to day, with a maximum CoV of 4.44%. Across different days, the maximum standard deviation was found to be 0.19kg, indicating that the computed forces tend to be close to the mean.

Fig. 6.

BandPass's accuracy for measuring random loads

Fig. 7.

BandPass's repeatability across multiple days

B. Dynamic Testing

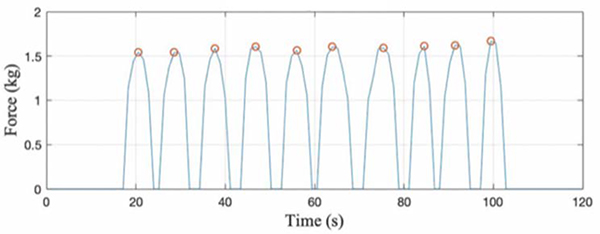

User performance was evaluated by analyzing the maximum force applied during each repetition of an exercise, peak-to-peak variation between repetitions, performance stability, and time taken to perform a repetition. Figure 8 shows the computed force data across 3 different days for the controlled T-lift exercise. For day 1, the mean peak was 1.68kg, standard deviation between peaks was 0.06kg, and CoV was 3.63%. For day 2, the mean peak was 1.61kg, standard deviation between peaks was 0.04kg, and CoV was 2.57%. For day 3, the mean peak was 1.63kg, standard deviation between peaks was 0.04kg, and CoV was 2.53%.

Fig. 8.

Controlled T-lift exercise performed by single user across 3 days

Across the 3 days of testing, the average computed peak was 1.64kg, and the standard deviation and CoV between the different days was 0.04kg and 2.15%, respectively.

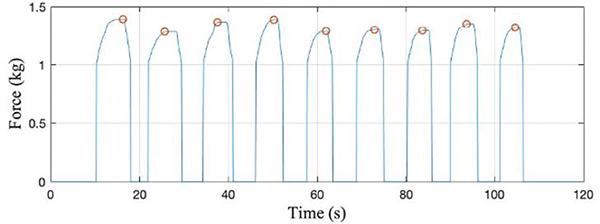

Figure 9 represents the data captured from BandPass as a user performed 10 repetitions of a bicep curl. In this instance, the user applied an average of 1.59 kg force during the exercise and had a 2.36% CoV between curls. Seated row testing (Fig. 10) yielded similar results where the mean force was 1.33kg, standard deviation was 0.40kg and CoV between rows was 3.30%. The similarities between repetition profiles suggest that classifying exercise type and confirming correct performance through shape matching may be viable, suggesting confidence in the system’s ability to monitor and identify other exercises.

Fig. 9.

Bicep curl performed by single user for 10 reps

Fig. 10.

Seated row performed by single user for 9 reps

C. Patient Study

Three (T-lift, bicep curl and seated row) of the four assigned exercises (T-lift, bicep curl, seated row and triceps extension) were completed by all participants. A total of 147 exercises were recorded during the study period: 36 T-lifts, 49 bicep curls, 36 seated rows, and 26 triceps extensions. Table I summarizes the relative measured force statistics that were collected throughout the study. The collected data indicated that there were differences in the number of repetitions, lengths of exercises, and number of sets performed by the different users. On average, patients spent the most time performing triceps extensions and the least time performing seated rows.

TABLE I.

Patient Study Exercise Summary

| Exercise | Force Mean (ADC) | Force SD (ADC) | Force CoV | Force Variance (ADC2) | Reps Mean (counts) | Reps SD (counts) | Reps CoV | Reps Variance (counts2) | Mean Duration (s) |

| T-Lift | 118.78 | 58.38 | 49.15 | 3407.83 | 12.12 | 7.09 | 58.5 | 50.32 | 86.8 |

| Bicep Curl | 70.38 | 42.91 | 60.97 | 1840.94 | 17.02 | 14.3 | 84.04 | 204.55 | 80.7 |

| Seated Row | 51.16 | 26.03 | 50.88 | 677.68 | 16.88 | 10.45 | 61.94 | 109.25 | 69.6 |

| Triceps Extension | 62.03 | 46.68 | 75.25 | 2179.05 | 14.12 | 8.73 | 61.85 | 76.27 | 162.4 |

V. Discussion

A remote force sensing BLE resistance exercise band system provides clinically relevant data on compliance and use of exercise training for clinicians and patients. The force sensing system described in this paper was tested in both a controlled single user environment and a multi-patient study demonstrating its ability to collect and display valuable information on user’s strength.

Calibrating each band took approximately 7 minutes to complete. Calibration error for the potentiometer was less than 5%. Minimal variation and noise for the same weights (during the 45s loading time) indicates that BandPass filters out non-linear loads as intended. It should be noted that loads were also applied at varying (non-linear) angles to assess whether it was necessary for loads to be applied exactly linear to the potentiometer. However, the calibration data remained unchanged, indicating that the sensor-casing design is limiting all potential multi-axial loads to a single dimension. The calibration load range was chosen to be 0.6kg-4.6kg, which meets the expected force that would be exerted by the older adult demographic. Force values computed outside of this range may not be reliable, therefore a more variable range scale (<0.6kg and >4.6kg) can be used during calibration to improve device reliability, particularly for lower peaks.

While the current calibration protocol results in a device that is 94% accurate, an autonomous, computer-controlled calibration protocol could offer a method to apply loads to the sensor with minimal variability while reducing the potential for user error or bias. Furthermore, a more automated system that does not rely on manually loading and unloading weights will streamline the calibration process and allow for devices to be calibrated in significantly less time.

While sensor calibration was performed in a stepwise fashion to allow for sensor stabilization at each load, loads were not all tested in increasing weight order during static bench top testing, since forces are applied dynamically during exercise. The validation error indicated that the device is not affected by the ordering of the loaded weights. The minimal change in error when the applied load increases or decreases is a critical result as the user’s exerted strength will follow a similar non-linear form during exercise. Static benchtop testing of the device indicated that the device has a sensitivity of 150g, which is an appropriate sensitivity level during resistance training. Using a smaller potentiometer can achieve higher sensitivity, improve accuracy and reduce stability errors, particularly at higher loads. The study indicated that the 2x factor of safety that was implemented to achieve 400% band elongation was too conservative, as the users consistently achieved 150–250% of band elongation. This means that less than half of the full voltage range was used. Transitioning to a smaller potentiometer would result in the full voltage range being used and would therefore enhance device sensitivity. Furthermore, a smaller potentiometer would also reduce the footprint and weight of the device, thereby improving its ergonomics and aesthetics.

Repeatability testing that was performed across multiple days showed the maximum standard deviation was 0.19kg. This highlights that BandPass can be used to measure and track longitudinal compliance with exercises and quantify force/strength during a single exercise session and over time. Furthermore, single user dynamic testing showed that BandPass can relay information on exercise performance such as average force exerted, time to complete a single rep, and time for a full exercise, etc. The repetition profiles can be used to classify exercise type and confirm correct performance through shape matching. Tracing a user’s performance data over time can viably track their progress and provide clinicians key metrics regarding patient compliance and response to different exercises. For instance, if a user is repeatedly unable to complete the number of repetitions or the exerted force declines over time, the clinician can alter the exercise or band to an easier one. An example of this was seen in the patient study where not all 7 patients completed the triceps extensions. When analyzing the Borg score, the triceps extension exercise received the highest perceived difficult score, attesting that the reason not all participants completed this exercise was due to its difficulty. Having this data available to clinicians can provide insightful feedback that can further individualize and dynamically enhance patients’ treatment plans.

The pilot patient study demonstrated BandPass’s capabilities beyond a controlled lab setting. Through this remote-sensing BLE resistance exercise band system, clinicians and patients could access novel data regarding the performed exercises. The device has the ability to measure force continuously over time during exercises, measure longitudinal compliance with exercises and quantify force/strength continuously over time. Together, these will allow for accurate tracking of strength, which can optimize a user’s training program allowing for a more tailored approach for treatment plans. The study’s results showed that older adults complete exercises at unequal proportions, and that there is a positive correlation between the perceived exertion, the number of repetitions and the length of the exercise. One limitation of this study, however, is that it was interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have impacted the patients’ general participation. Overall, the pilot study demonstrated that BandPass is a viable non-invasive solution for detection and acquisition of home-based longitudinal healthcare data to remotely monitor the health of at-risk older adults.

VI. Conclusion

This paper presents a remote-sensing BLE resistance exercise band system that accurately records and transmits data to a cloud-based server for processing. The value proposition of this system lies in its ability to connect clinicians to their patients, allowing for remote monitoring of prescribed in-home resistance exercise programs. BandPass is an mHealth modality that can alter the status quo for engaging in resistance-based exercise programs for at-risk older adults, engaging seniors to complete their therapy and allowing clinicians to remotely monitor and advise patients, reducing the need for direct encounters. The system addresses a service gap by using technology to improve patient self-awareness of health that can integrate into routine care. With an increasing shortage of geriatricians and physical therapists [29], harnessing this technology may redefine novel processes for enhancing clinical oversight in an overburdened system by offering innovative and practical ways of integrating such devices into routine care of at home monitoring of physical therapy. This foundation provides a basis for a future, randomized efficacy trial that may improve the health of a rapidly aging population at risk for sarcopenia by enhancing physical function via remote monitoring interventions to reduce costs [30].

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank all the participants and the staff at the Center for Health and Aging at Dartmouth for testing BandPass. Thank you to Emily Wechsler for her initial work on the connected band device. The authors would also like to thank the staff of Thayer School of Engineering at Dartmouth College for use of the facilities and for their assistance.

Work was supported in part by grant number K23-AG051681 from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institute of Health, and a pilot grant from the NIDA/NIH P30DA029926. CLP is also supported by the Burroughs-Wellcome Fund: Big Data in the Life Sciences at Dartmouth. Patent pending for BandPass. CLP, CMM, SM, RJH, JAB have equity in SynchroHealth, LLC.

Contributor Information

Suehayla Mohieldin, Thayer School of Engineering, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, USA.

John A. Batsis, Division of Geriatric Medicine, Department of Nutrition, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Colin M. Minor, Thayer School of Engineering, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, USA

Ryan J. Halter, Thayer School of Engineering, Geisel School of Medicine, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, USA

Curtis L. Petersen, The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, USA

References

- [1].Government US. Census Bureau Statistics. 2012. Accessed January 20th, 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Batsis JA, Barre LK, Mackenzie TA, Pratt SI, Lopez-Jimenez F, Bartels SJ. Variation in the prevalence of sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity in older adults associated with different research definitions: dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2004. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(6):974–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lacroix A, Hortobágyi T, Beurskens R, Granacher U. Effects of Supervised vs. Unsupervised Training Programs on Balance and Muscle Strength in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2017;47(11):2341–2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Pacifico J, Geerlings MAJ, Reijnierse EM, Phassouliotis C, Lim WK, Maier AB. Prevalence of sarcopenia as a comorbid disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Exp Gerontol. 2020;131:110801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Landi F, Schneider SM, et al. Prevalence of and interventions for sarcopenia in ageing adults: a systematic review. Report of the International Sarcopenia Initiative (EWGSOP and IWGS). Age Ageing. 2014;43(6):748–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bianchi L, Abete P, Bellelli G, et al. Prevalence and Clinical Correlates of Sarcopenia, Identified According to the EWGSOP Definition and Diagnostic Algorithm, in Hospitalized Older People: The GLISTEN Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(11):1575–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chang SF, Lin PL. Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis of the Association of Sarcopenia With Mortality. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2016;13(2):153–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Areta JL, Burke LM, Camera DM, et al. Reduced resting skeletal muscle protein synthesis is rescued by resistance exercise and protein ingestion following short-term energy deficit. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2014;306(8):E989–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Freburger JK, Khoja S, Carey TS. Primary Care Physician Referral to Physical Therapy for Musculoskeletal Conditions, 2003–2014. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(6):801–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019;48(1):16–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Dent E, Morley JE, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, et al. International Clinical Practice Guidelines for Sarcopenia (ICFSR): Screening, Diagnosis and Management. J Nutr Health Aging. 2018;22(10):1148–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lazarus NR, Izquierdo M, Higginson IJ, Harridge SDR. Exercise Deficiency Diseases of Ageing: The Primacy of Exercise and Muscle Strengthening as First-Line Therapeutic Agents to Combat Frailty. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19(9):741–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Law TD, Clark LA, Clark BC. Resistance Exercise to Prevent and Manage Sarcopenia and Dynapenia. Annu Rev Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;36(1):205–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Tsekoura M, Billis E, Tsepis E, et al. The Effects of Group and Home-Based Exercise Programs in Elderly with Sarcopenia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Med. 2018;7(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Donat H, Ozcan A. Comparison of the effectiveness of two programmes on older adults at risk of falling: unsupervised home exercise and supervised group exercise. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21(3):273–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Noah B, Keller MS, Mosadeghi S, et al. Impact of remote patient monitoring on clinical outcomes: an updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. npj Digital Medicine. 2018;1(1):20172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Resnick B, Orwig D, Magaziner J, Wynne C. The effect of social support on exercise behavior in older adults. Clin Nurs Res. 2002;11(1):52–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Nicolson PJA, Hinman RS, Wrigley TV, Stratford PW, Bennell KL. Self-reported Home Exercise Adherence: A Validity and Reliability Study Using Concealed Accelerometers. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018;48(12):943–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Evenson KR, Goto MM, Furberg RD. Systematic review of the validity and reliability of consumer-wearable activity trackers. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Alinia P, Cain C, Fallahzadeh R, Shahrokni A, Cook D, Ghasemzadeh H. How Accurate Is Your Activity Tracker? A Comparative Study of Step Counts in Low-Intensity Physical Activities. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2017;5(8):e106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lyons EJ, Swartz MC, Lewis ZH, Martinez E, Jennings K. Feasibility and Acceptability of a Wearable Technology Physical Activity Intervention With Telephone Counseling for Mid-Aged and Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2017;5(3):e28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Muellmann S, Forberger S, Mollers T, Broring E, Zeeb H, Pischke CR. Effectiveness of eHealth interventions for the promotion of physical activity in older adults: A systematic review. Prev Med. 2018;108:93–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Appelboom G, Camacho E, Abraham ME, et al. Smart wearable body sensors for patient self-assessment and monitoring. Arch Public Health. 2014;72(1):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Gamm L, Hutchison L, Bellamy G, Dabney BJ. Rural healthy people 2010: identifying rural health priorities and models for practice. J Rural Health. 2002;18(1):9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Donat H, Ozcan A. Comparison of the effectiveness of two programmes on older adults at risk of falling: unsupervised home exercise and supervised group exercise. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21(3):273–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bunn JA, Navalta JW, Fountaine CJ, Reece JD. Current State of Commercial Wearable Technology in Physical Activity Monitoring 2015–2017. Int J Exerc Sci. 2018;11(7):503–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Petersen CL, Halter R, Kotz D, Loeb L, Cook S, Pidgeon D, Christensen BC, Batsis JA. Using Natural Language Processing and Sentiment Analysis to Augment Traditional User-Centered Design: Development and Usability Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020. August 7;8(8):e16862. doi: 10.2196/16862. PMID: 32540843; PMCID: PMC7442942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Borg GA. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1982;14(5):377–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lester PE, Dharmarajan TS, Weinstein E. The Looming Geriatrician Shortage: Ramifications and Solutions. J Aging Health. 2019:898264319879325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Mann WC, Ottenbacher KJ, Fraas L, Tomita M, Granger CV. Effectiveness of assistive technology and environmental interventions in maintaining independence and reducing home care costs for the frail elderly. A randomized controlled trial. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8(3):210–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]