Abstract

Introduction

Smoking and the use of other nicotine-containing products is rewarding in humans. The self-administration of nicotine is also rewarding in male rats. However, it is unknown if there are sex differences in the reward-enhancing effects of nicotine self-administration and if the rewarding effects of nicotine change over time.

Methods

Rats were prepared with catheters and intracranial self-stimulation (ICSS) electrodes to investigate the effects of nicotine and saline self-administration on reward function. A decrease in thresholds in the ICSS procedure reflects an enhancement of reward function. The ICSS parameters were determined before and after the self-administration sessions from days 1 to 10, and after the self-administration sessions from days 11 to 15.

Results

During the first 10 days, there was no sex difference in nicotine intake, but during the last 5 days, the females took more nicotine than the males. During the first 10 days, nicotine self-administration did not lower the brain reward thresholds but decreased the response latencies. During the last 5 days, nicotine lowered the reward thresholds and decreased the response latencies. An analysis with the 5-day averages (days 1–5, 6–10, and 11–15) showed that the reward enhancing and stimulatory effects of nicotine increased over time. There were no sex differences in the reward-enhancing and stimulatory effects of nicotine. The nicotinic receptor antagonist mecamylamine diminished the reward-enhancing and stimulatory effects of nicotine.

Conclusion

These findings indicate that the rewarding effects of nicotine self-administration increase over time, and there are no sex differences in the reward-enhancing effects of nicotine self-administration in rats.

Implications

This study investigated the rewarding effect of nicotine and saline self-administration in male and female rats. The self-administration of nicotine, but not saline, enhanced brain reward function and had stimulatory effects. The rewarding effects of nicotine increased over time in the males and the females. Despite that the females had a higher level of nicotine intake than the males, the reward-enhancing effects of nicotine self-administration were the same. These findings suggest that in new tobacco and e-cigarette users, nicotine’s rewarding effects might increase quickly, and a higher level of nicotine use in females might not translate into greater rewarding effects.

Introduction

Tobacco use is mildly rewarding, enhances cognitive function, and contributes to a feeling of relaxation and calmness.1,2 These positive reinforcing effects of nicotine play a key role in the initiation of tobacco smoking and electronic-cigarette (e-cig) use. Smoking cessation leads to impaired reward function, cognitive impairments, and intense craving, which contributes to relapse.3,4 In the United States alone, there are more than 30 million people who smoke tobacco products, and smoking and secondhand smoke exposure leads to the death of 480 000 people per year.5,6 Although there has been a gradual decrease in tobacco use, there has been a strong increase in the use of e-cigs.7,8 Therefore, it is essential to know which factors contribute to the initiating of tobacco and e-cig use.

The rewarding properties of tobacco smoke, e-cig aerosol, and nicotine have been investigated in animal models.9–11 A wide range of doses of nicotine induce place preference in the conditioned place preference procedure.12 Furthermore, noncontingent nicotine administration lowers the brain reward thresholds in the intracranial self-stimulation (ICSS) procedure.10,13 A decrease in brain reward thresholds reflects a potentiation of brain reward function. Nicotine also has stimulatory effects, leading to shorter response latencies in the ICSS procedure and increased locomotor activity.13,14 On a similar note, passive exposure to tobacco smoke potentiates brain reward function and decreases response latencies in rats in the ICSS procedure.11

There are no sex differences in the reward-enhancing effects of noncontingent nicotine administration in the ICSS procedure in adult rats.15 Place conditioning studies have reported conflicting findings regarding sex differences in the rewarding effects of nicotine. Some studies suggest that males are more sensitive to the rewarding effects of nicotine in place conditioning procedures, and others suggest that females are more sensitive.16,17 Our group and others showed that nicotine self-administration in male rats lowers the brain reward thresholds in the ICSS procedure.18–20 The present study expands upon this work by determining whether there are sex differences in the rewarding and stimulatory effects of nicotine self-administration in the ICSS procedure. Furthermore, male and female saline self-administration groups were included as controls for the nicotine self-administration groups. The present study suggests that there are no sex differences in the reward-enhancing effects of nicotine self-administration, and that the rewarding effects of nicotine self-administration increase over time in adult rats.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult male and female Wistar rats were purchased (Charles River, Raleigh, NC). The rats were socially housed (two per cage) with a rat of the same sex in a climate-controlled vivarium on a reversed 12 hours light-dark cycle (light off at 7 am ). Food and water were available ad libitum in the home cage. The experimental protocols were approved by the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Drugs

(−)-Nicotine hydrogen tartrate and mecamylamine hydrochloride was purchased from Sigma (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and dissolved in sterile saline (0.9% sodium chloride). The rats self-administered 0.1 mL/infusion intravenously (IV) of a nicotine solution or sterile saline. Mecamylamine was administered subcutaneously (SC) in a volume of 1 mL/kg body weight. Nicotine doses are expressed as base and the mecamylamine dose is expressed as salt.

Experimental Design

Adult male (n = 22) and female (n = 21) rats were prepared with ICSS electrodes in the medial forebrain bundle and trained on the ICSS procedure.21,22 The rats were singly housed after the implantation of the ICSS electrodes. The rats were also trained to respond for food pellets (45 mg, F0299, Bio-Serv, Frenchtown, NJ) in operant self-administration chambers under a fixed ratio (FR)-1s and FR1-TO10s schedule (Supplementary Materials).23–25 Food training was done in the morning, and ICSS training in the afternoon. After completing the training sessions, the rats were prepared with catheters in the jugular vein.26 Baseline brain reward thresholds and response latencies were determined on three consecutive days before the implantation of the catheters. From days 1 to 10, the rats self-administered nicotine or saline daily for 1 hour (0.03 mg/kg/inf, 5 d/week) starting at 9 am. The thresholds and latencies were assessed immediately before and after the self-administration sessions. From days 11 to 15, the brain reward thresholds and response latencies were only measured immediately after the self-administration sessions. On days 16 and 17, the rats received saline or mecamylamine (3 mg/kg, SC) 15 minutes prior to the self-administration session, and the rats were tested in the ICSS procedure immediately after the self-administration sessions. The study was conducted with 7 male-saline, 15 male-nicotine, 9 female-saline, and 12 female-nicotine rats. Four rats were excluded from the study (2 males and 2 females) because of partially blocked catheters at the end of the 10-day period, and two more rats were excluded at the end of the 15-day period (1 male and 1 female). The main dependent variable of interest in the present study was the brain reward thresholds. We expected no effect of saline self-administration on reward thresholds, and little variability between reward thresholds of the rats after saline self-administration. Therefore, we were able to conduct the study with relatively small groups of saline self-administration animals (n = 7–9 group/sex).

Electrode Implantations and ICSS Procedure

The rats were anesthetized with an isoflurane and oxygen vapor mixture and placed in a stereotaxic frame (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA). Electrodes were implanted in the medial forebrain bundle with the incisor bar set 5 mm above the interaural line (anterior-posterior −0.5 mm, medial-lateral ±1.7 mm, dorsal-ventral −8.3 mm from dura).27 The rats were trained on a modified discrete-trial ICSS procedure in operant conditioning chambers (Med Associates, Georgia, VT). The operant conditioning chambers were housed in sound-attenuating chambers (Med Associates). A 5-cm wide metal response wheel was centered on a sidewall, and a photobeam detector recorded every 90 degrees of rotation. Brain stimulation was delivered by constant current stimulators (Model 1200C, Stimtek, Acton, MA). The rats were trained to turn the wheel on a fixed ratio 1 (FR1) schedule of reinforcement. Each quarter-turn of the wheel resulted in the delivery of a 0.5-second train of 0.1 ms cathodal square-wave pulses at a frequency of 100 Hz. After the acquisition of responding for stimulation on the FR1 schedule (100 reinforcements within 10 min), the rats were trained on a discrete-trial current-threshold procedure. The discrete-trial current-threshold procedure is a modification of a task developed by Kornetsky and Esposito,28 and previously described in detail.25,29 Each trial began with the delivery of a noncontingent electrical stimulus and this was followed by a 7.5-second response window during which the animals could respond for a second identical stimulus. A response during this 7.5-second response window was labeled a positive response and the lack of a response was labeled a negative response. During the 2-second period immediately after a positive response, additional responses had no consequences. The intertrial interval (ITI), which followed a positive response or the end of the response window, had an average duration of 10 seconds (ranging from 7.5 to 12.5 seconds). Responses during the ITI resulted in a 12.5 seconds delay of the onset of the next trial. During the training sessions, the duration of the ITI and delay periods induced by time-out responses were increased until the animals performed consistently at standard test parameters. The training was completed when the animals responded correctly to more than 90% of the noncontingent electrical stimuli. It took 2–3 weeks of training for most rats to meet this response criterion. The rats were then tested on the current-threshold procedure in which stimulation intensities varied according to the classical psychophysical method of limits. Each test session consisted of four alternating series of descending and ascending current intensities starting with a descending sequence. Blocks of three trials were presented to the rats at a given stimulation intensity, and the intensity was altered between blocks of trials by 5 µA steps. The initial stimulus intensity was set 30 µA above the baseline current threshold for each animal. Each test session typically lasted 30–40 minutes and provided two dependent variables for behavioral assessment (brain reward thresholds and response latencies). The brain reward threshold (µA) was defined as the midpoint between stimulation intensities that supported responding and stimulation intensities that failed to support responding. The response latency (s) was defined as the time interval between the beginning of the noncontingent stimulus and a response. A decrease in reward thresholds is indicative of an increase in reward function.28 Drugs with sedative effects increase the response latencies, and stimulants decrease the response latency.13,30

Intravenous Catheter Implantation and Operant Responding for Nicotine

The rats were anesthetized with an isoflurane-oxygen vapor mixture (1%–3%) and prepared with a catheter in the right jugular vein. The surgery was conducted as described in our previous studies.23,26,31 The catheters consisted of polyurethane tubing (length 15 cm, inner diameter 0.64 mm, outer diameter 1.0 mm, model 3Fr, Instech Laboratories, Plymouth Meeting, PA). The right jugular vein was isolated, and the catheter was inserted to a depth of 2.5 cm. The tubing was then tunneled subcutaneously and connected to a vascular access button (Instech Laboratories). The button was exteriorized through a small, 1.5-cm incision between the scapulae. After the surgery, the rats were given at least 4 days to recover. The rats received infusions with the antibiotic gentamycin (4 mg/kg IV, Sigma–Aldrich) for 7 days. A sterile heparin/glycerol solution (0.1 mL, 500 U/mL, SAI Infusion Technologies, Lake Villa, IL) was infused into the catheter after the administration of the antibiotic or after the self-administration sessions. The animals received carprofen (5 mg/kg, SC) once daily for 48 hours after the surgery. After recovery, the rats self-administered nicotine (0.03 mg/kg/infusion) or saline for 1 h/day under an FR1-TO10s schedule for a total of 17 days. The maximum number of nicotine infusions was set to 20 on the first day to diminish the aversive effects of a high dose of nicotine. Active lever (right lever, RL) responding resulted in the delivery of a nicotine or saline infusion (0.1 mL infused over a 5.6-second period). The infusions were paired with a cue light, which remained illuminated throughout the time-out period. Inactive lever (left lever, LL) responses were recorded but did not have scheduled consequences. Both levers were retracted during the 10-second time-out period. The self-administration sessions were conducted 5 days per week. During the 17-day self-administration period, the rats received about 95% of their normal ad lib food intake in the home cage. The rats were fed immediately after the operant sessions. Catheter patency was assessed after the last self-administration session by infusing 0.2 mL of the ultra-short action barbiturate Brevital (1% methohexital sodium). Rats with patent catheters displayed loss of muscle tone within a few seconds after infusion. If the rats did not show this response, their self-administration data were excluded from the analysis. Rats were also excluded when it became difficult to flush the catheter with saline.

Statistics

Dependent variables in the self-administration procedure were responses on the active and inactive lever, the number of infusions, and nicotine intake (mg/kg). The nicotine self-administration sessions (days 1–15) were analyzed using a three-way ANOVA, with treatment condition (saline and nicotine self-administration) and sex as between-subject factors, and session (days) as within-subjects factor. The dependent variables in the ICSS procedure were brain reward thresholds and response latencies. The brain reward thresholds and the response latencies were expressed as a percentage of the 3-day baseline that was obtained prior to the implantation of the catheters. Brain reward thresholds and response latencies were analyzed using a three-way ANOVA, with treatment condition (saline and nicotine self-administration) and sex as between-subject factors, and session (days) as within-subjects factor. The study had sufficient statistical power (80%) to detect sex and treatment effects (effect size f = 0.3) on ICSS and drug intake parameters. For all statistical analyses, significant interactions in the ANOVA were followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc tests to determine which groups differed from each other. p Values that were less or equal to .05 were considered significant. Significant main effects, interaction effects, and post hoc comparisons are reported in the Results section. Data were analyzed with IBM SPSS Statistics version 27 and GraphPad Prism version 8.4.3.

Results

Nicotine Self-administration (Days 1–10)

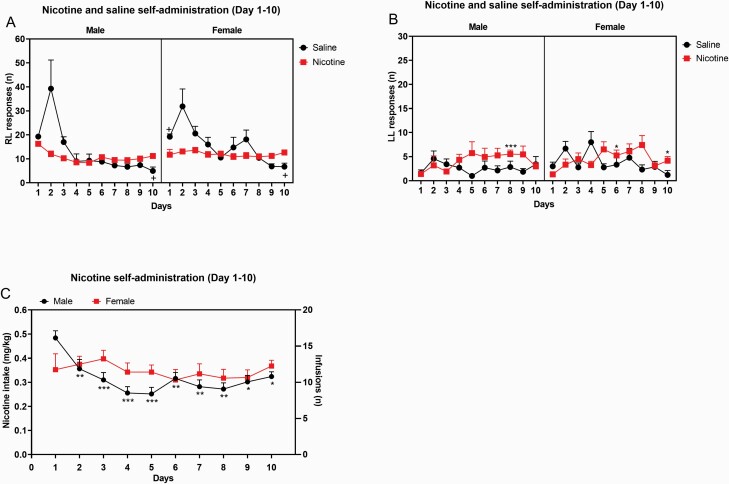

During the first 10 self-administration days, the saline rats responded more on the active lever than the nicotine rats (Treatment, F1,39 = 9.722, p < .01, Figure 1A and Supplementary Table S1), and the females responded more on the active lever than the males (Sex, F1,39 = 4.228, p < .05). Responding on the active lever decreased over time, and this was more pronounced in rats that self-administered saline than nicotine (Time, F9,351 = 19.28, p < .0001; Time × Treatment, F9,351 = 13.8325, p < .0001). The males started with a relatively high level of nicotine intake and this was followed by a decline in intake, while nicotine intake in the females was relatively stable (Time × Sex, F9,351 = 1.883, p = .053 [trend]). A separate analysis with only the nicotine or only the saline rats was conducted to provide more insight into sex differences in nicotine and saline self-administration. In the nicotine group, responding on the active lever in the males initially decreased and then stabilized while in the females responding on the active lever was relatively stable (Time, F9,225 = 3.311, p < .05; Time × Sex, F9,225 = 2.736, p < .01; Supplementary Figure S1A). In the saline group, responding on the active lever changed over time, but sex did not affect responding on the active lever (Time, F9,126 = 11.32, p < .0001, Supplementary Figure S1B). During the first 10 self-administration days, operant responding on the inactive lever increased in the nicotine group and decreased in the saline group (Time, F9,351 = 1.867, p = .056; Time × Treatment, F9,351 = 2.777, p < .01, Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Acquisition of nicotine and saline self-administration in adult male and female rats. Adult male and female rats self-administered nicotine or saline from days 1 to 10. Active lever responding (A), inactive lever responding (B), and total nicotine intake (C) are depicted. Plus signs indicate significant different from rats of the same sex in the nicotine group (A). Asterisks indicate a higher level of responding on the inactive lever compared to rats of the same sex on day 1 (B), or a lower level of nicotine intake compared to male rats on day 1 (C). +,,*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001. Male-saline n = 7, male-nicotine n = 15, female-saline n = 9, and female-nicotine rats n = 12. Abbreviations: RL, right lever; LL, left lever. Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

The saline rats took more infusions than the nicotine rats (Treatment, F1,39 = 8.92, p < .01, Supplementary Figure S2A, Supplementary Table S1), and there was a trend for the females to take more infusions than the males (Sex, F1,39 = 3.458, p = .07). The number of infusions decreased over time, and this decrease was greater in the saline rats than the nicotine rats (Time, F9,351 = 20.362, p < .0001; Time × Treatment, F9,351 = 14.303, p < .0001). The males took somewhat more infusion during the first few days and displayed a greater decline over time (Time × Sex, F9,351 = 2.114, p < .05). There was no main effect of sex on nicotine intake (Figure 1C). Nicotine intake decreased over time, and this decrease was greater in the males than the females (Time, F9,225 = 3.742, p < .0001; Time × Sex, F9,225 = 2.548, p < .01).

Nicotine Self-administration (Days 11–15)

From days 11 to 15, the females had a higher level of responding on the active lever than the males (Sex, F1,35 = 9.61, p < .01, Figure 2A), and the nicotine rats had a higher level of responding on the active lever than the saline rats (Treatment, F1,35 = 13.601, p < .001). Responding on the active lever slightly decreased over time (F4,140 = 2.917, p < .05). The female rats had a higher level of responding on the inactive lever than the males (Sex, F1,35 = 4.406, p < .05, Figure 2B), and the nicotine rats had a higher level of responding on the inactive lever than the saline rats (Treatment, F1,35 = 5.672, p < .05).

Figure 2.

Maintenance of nicotine and saline self-administration in adult male and female rats. Adult male and female rats self-administered nicotine or saline from days 11 to 15. Active lever responding (A), inactive lever responding (B), and total nicotine intake (C) are depicted. The nicotine rats took more infusions than the saline rats, and the females took more infusions than the males. Male-saline n = 7, male-nicotine n = 13, female-saline n = 9, and female-nicotine rats n = 10. Abbreviations: RL, right lever; LL, left lever. Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

The females took more infusions than the males (Sex, F1,35 = 10.225, p < .01, Supplementary Figure S2B), and the nicotine rats took more infusions than saline rats (Treatment, F1,35 = 14.646, p < .001). The number of infusions decreased over time (F4,140 = 3.154, p < .05). Nicotine intake was higher in the females than the males (Sex, F1,21 = 15.182, p < .001, Figure 2C).

Brain Reward Thresholds and Response Latencies

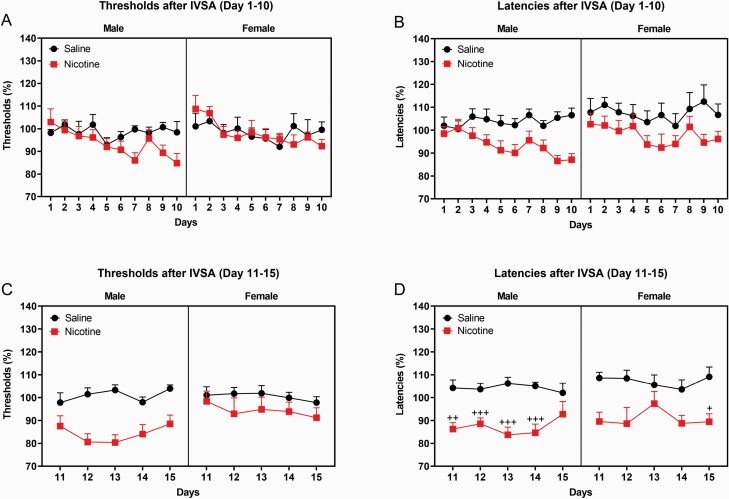

The brain reward thresholds and response latencies were determined before and after the implantation of the catheters. Implantation of the catheters did not affect the brain reward thresholds or the response latencies (Supplementary Figure S3). From days 1 to 10, the brain reward thresholds of the rats before the self-administration sessions were not affected by the self-administration of nicotine or saline or the sex of the rats (Supplementary Figure S4A). The self-administration of nicotine and the sex of the rats did not affect the brain reward thresholds immediately after the self-administration sessions (Figure 3A). However, the brain reward thresholds changed slightly over time (F9,351 = 2.148, p < .05). From days 1 to 10, the response latencies before the self-administration sessions changed slightly over time (F9,351 = 2.226, p < .05, Supplementary Figure S4B). The self-administration of nicotine decreased the response latencies of the rats immediately after the self-administration sessions (F1,39 = 9.829, p < .01, Figure 3B). The sex of the rats did not affect the response latencies immediately after the self-administration sessions.

Figure 3.

Brain reward thresholds and response latencies after nicotine and saline self-administration. Brain reward thresholds and response latencies were measured after the self-administration sessions from days 1 to 10 (A, B) and from days 11 to 15 (C, D). During the first 10 sessions, nicotine self-administration did not affect the reward thresholds but lowered the response latencies. During the last five sessions, nicotine self-administration decreased the brain reward thresholds and the response latencies. Plus signs indicate shorter response latencies compared to rats of the same sex on the same testing day. +p < .05; ++p < .01; +++p < .001. Male-saline n = 7, male-nicotine n = 15, female-saline n = 9, and female-nicotine rats n = 12 (A, B). Male-saline n = 7, male-nicotine n = 13, female-saline n = 9, and female-nicotine rats n = 10 (C, D). Abbreviation: IVSA, intravenous self-administration. Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

From days 11 to 15, nicotine self-administration decreased the reward thresholds immediately after the self-administration sessions (Treatment, F1,35 = 14.779, p < .0001, Figure 3C), and this was not affected by the sex of the rats. Nicotine self-administration also decreased the response latencies immediately after the self-administration sessions (Treatment, F1,35 = 18.756, p < .0001, Figure 3D). The nicotine-induced decrease in response latencies was different in the males and females (Time × Sex × Treatment, F4,140 = 2.677, p < .05). The post hoc showed that nicotine decreased the response latencies in the males from days 11 to 14 and in the females on day 15.

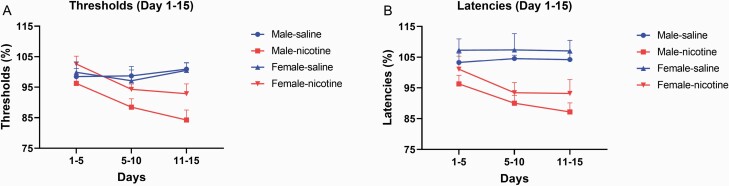

An additional analysis was conducted with the thresholds and response latencies after nicotine self-administration (days 1–15, 5-day blocks). The reward thresholds decreased over time and this effect was greater in the rats that self-administered nicotine than saline (Time, F2,70 = 6.579, p < .01; Treatment, F1,35 = 5.49, p < .05, Time × Treatment, F2,70 = 8.74, p < .0001; Figure 4A). On a similar note, the latencies decreased over time, and the decrease in latencies was greater in the rats that self-administered nicotine than saline (Time, F2,70 = 6.273, p < .01; Treatment, F1,35 = 13.508, p < .001; Time × Treatment, F2,70 = 8.066, p < .01, Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Decrease in brain reward thresholds and response latencies after nicotine self-administration. Nicotine self-administration lead to gradual decrease in brain reward thresholds (A) and response latencies (B). Male-saline n = 7, male-nicotine n = 13, female-saline n = 9, and female-nicotine rats n = 10. Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

Nicotinic Receptor Blockade, Self-administration and Reward Function

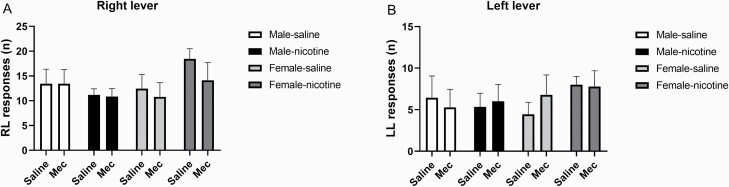

Mecamylamine or sex did not affect responding on the active or the inactive lever in the nicotine and the saline groups (Figure 5). However, pretreatment with mecamylamine diminished the nicotine self-administration induced decrease in brain reward thresholds (Nicotine treatment, F1,33 = 5.339, p < .05; Mecamylamine treatment, F1,33 = 48.386, p < .0001; Nicotine treatment × Mecamylamine treatment, F1,33 = 5.349, p < .05, Figure 6A) and response latencies (Nicotine treatment, F1,33 = 6.159, p < .05; Mecamylamine treatment, F1,33 = 42.311, p < .0001; Nicotine treatment × Mecamylamine treatment, F1,33 = 4.271, p < .05, Figure 6B).

Figure 5.

Effects of nicotinic receptor blockade on nicotine and saline self-administration. The effects of mecamylamine (Mec; 3 mg/kg, SC) on operant responding for nicotine and saline (A, active lever; B, inactive lever) was investigated. Mecamylamine did not affect responding on the active or inactive lever in the saline and nicotine self-administration groups. Male-saline n = 7, male-nicotine n = 12, female-saline n = 9, and female-nicotine rats n = 9. Abbreviations: RL, right lever; LL, left lever; mec, mecamylamine. Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

Figure 6.

Effects of nicotinic receptor blockade on reward thresholds and response latencies. The effects of mecamylamine (Mec; 3 mg/kg, SC) on brain reward thresholds (A) and response latencies (B) after nicotine and saline self-administration were investigated. Abbreviations: mec, mecamylamine. Male-saline n = 7, male-nicotine n = 12, female-saline n = 9, and female-nicotine rats n = 9. Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

Discussion

In the present study, we determined if there are sex differences in the effect of nicotine self-administration on brain reward function. We found that the rats self-administered more saline during the first 10 sessions and more nicotine during the last 5 sessions. The females self-administered more nicotine and saline than the males during the 15-day self-administration period. The self-administration of nicotine decreased the response latencies during the first 10 days. Furthermore, nicotine self-administration decreased the brain reward thresholds and the response latencies during the last 5 days. There were no sex differences in the effects of nicotine self-administration on the brain reward thresholds and the response latencies. Pretreatment with mecamylamine prevented the reward enhancing and stimulatory effects of nicotine self-administration. Overall, these findings indicate that females self-administer more nicotine and saline than males, but there are no sex differences in the rewarding and stimulatory effects of nicotine self-administration.

Interestingly, there was a high level of operant responding for saline in the present study. During the first 10 self-administration days, the rats took more saline than nicotine infusions. The high level of responding for saline might have been due to the fact that the rats were trained to respond for food pellets before the self-administration sessions. During the food training sessions, a visual stimulus (cue light) was paired with the food reward. Because the rats were mildly food deprived during the food training sessions, they may have assigned a high incentive value to the conditioned stimulus (CS, visual stimulus).32–34 Previous studies investigated the role of CS in the extinction of operant responding for food pellets. These studies showed a rapid extinction of operant responding when responding on the active lever did not lead to food delivery, and no CS was presented.35,36 When the rats did not receive food pellets or the CS, operant responding completely extinguished in three testing days.35,36 In contrast, rats maintained a relatively high level of responding when they did not receive food pellets but continued to be exposed to the CS.35 This is in line with other reports that showed that cues associated with rewarding stimuli can maintain operant responding. Alcohol-related cues maintain a high level of operant responding in nonhuman primates when water was substituted for alcohol.37 Similarly, cues associated with nicotine and morphine self-administration maintain a high level of operant responding after saline is substituted for the nicotine or morphine.38,39 Interestingly, visual cues do not necessarily have to be paired with rewarding stimuli to increase operant responding. Both mice and rats acquire operant responding for visual stimuli.40,41 Furthermore, operant responding for intravenous saline is two to three times higher when saline self-administration is paired with a visual stimulus.42 Therefore, in the present study, the visual cue might have played a role in the high level of operant responding for saline. Visual cue lights are reinforcing by themselves and after the cues have been paired with rewarding food pellets or drugs the animals attribute incentive value to the cues.

In the present study, the CS maintained a high level of responding in the saline self-administration group. However, the saline self-administration sessions did not lead to a decrease in brain reward thresholds. Therefore, this suggests that operant responding for the food-paired CS does not lower the brain reward thresholds. During the nicotine self-administration sessions, the delivery of nicotine is also paired with the visual stimulus. However, in the present study it was not determined if operant responding for the nicotine-paired CS (without nicotine delivery) affects the reward thresholds. Additional work needs to be done to determine if operant responding for a nicotine-paired CS affects reward thresholds in the ICSS procedure.

The dual-reinforcement model proposes that in nicotine self-administration studies, operant responding is maintained by the reinforcing properties of nicotine and non-nicotine stimuli.42,43 Animal studies have shown that nicotine self-administration levels are higher when nicotine self-administration is coupled with the presentation of a cue light above the active lever and the turning off of the chamber light.38,44 However, it has also been shown that the effect of the cue light on nicotine self-administration is smaller than the effect of the cue light and the chamber light combined.44 In the present study, a cue light was presented when the rats met the response requirements, but there were no changes in the chamber light (chamber light was off throughout the self-administration sessions). Overall, based on our studies and the work of other investigators, it is highly likely that environmental cues such as the cue light contributed to the self-administration of nicotine.38,44

In the present study, we determined if there were sex differences in the effects of nicotine self-administration on brain reward thresholds and response latencies. During the first ten nicotine self-administration sessions, there was no difference in nicotine intake between males and females. During the last five sessions, the females had a higher level of nicotine intake than males. During the first 10 sessions, nicotine intake did not decrease the reward thresholds but decreased the response latencies to a similar degree in the males and the females. During the last five sessions, nicotine intake decreased the brain reward thresholds and response latencies to a similar degree in the males and the females. It is interesting to note that there were no sex differences in the rewarding and stimulatory effects of nicotine self-administration. This is in line with a previous study in which we found no sex differences in the rewarding effects of noncontingent nicotine administration in the ICSS procedure.15 Furthermore, we found that passive exposure to tobacco smoke led to a similar decrease in brain reward thresholds in adult male and female rats.11 Place conditioning procedures have also been used to determine if there are sex differences in the rewarding effects of nicotine. These studies indicate that nicotine induces place preference in male and female rodents but that higher doses of nicotine are required in females.17,45 It has also been reported that an intermediate dose of nicotine (0.2 mg/kg) induces similar place preference in males and females but that higher doses are rewarding in females and aversive in males.16 Our finding is in agreement with these place conditioning studies. The place conditioning studies suggest that higher doses of nicotine are needed in females to induce place preference and that higher doses of nicotine are not aversive in females. Interestingly, in our self-administration study, we found that the females had a significantly higher level of nicotine intake, but there were no sex differences in the effects of nicotine intake on the reward thresholds and latencies. This suggests that although the females take more nicotine than males, the effects on reward function are the same. This somewhat diminished response to the reward-enhancing effects of nicotine could potentially explain why females are more vulnerable to tobacco use and it is harder for females to quit smoking.46

It is interesting to note that treatment with mecamylamine did not affect the self-administration of nicotine but diminished the reward-enhancing and stimulatory effects of nicotine. In previous studies, mecamylamine decreased nicotine self-administration in rats.47,48 It has been reported that mecamylamine increases (high nicotine dose), decreases (low nicotine dose), or does not affect the oral nicotine intake in rodents.49,50 Thus, suggesting that the effects of mecamylamine might be affected by the nicotine dose and other experimental conditions. It is well established that in humans mecamylamine diminishes the rewarding effects of smoking and induces a compensatory increase in smoking.51–54 In the present study, mecamylamine diminished the reward-enhancing and stimulatory effects of nicotine self-administration. This is in agreement with studies that showed that nicotinic receptor blockade diminishes the rewarding effects of noncontingent nicotine administration in the ICSS and place preference procedure in rodents.10,55,56 In this experiment with mecamylamine, saline self-administration groups were included as well. The rats had a high level of operant responding for saline and there was no difference in operant responding for nicotine and saline. This underscores that animals that have received food training have a high level of operant responding for saline, and that it is therefore critical to include saline self-administration control groups in drug self-administration studies. Importantly, only operant responding for nicotine led to a decrease in brain reward thresholds and response latencies. Mecamylamine did not affect operant responding for saline and did not affect the brain reward thresholds and latencies of rats that self-administered saline. Overall, our finding is in line with previous studies that showed that nicotinic receptor blockade diminishes the rewarding effects of noncontingent nicotine administration in rodents and smoking in humans.

It remains to be determined why in the present study mecamylamine did not decrease nicotine self-administration but other studies reported that mecamylamine decreases operant responding for nicotine.47,48 It has been established that nicotinic receptor blockade diminishes the rewarding effects of nicotine and that thereby mecamylamine may decrease nicotine intake.10,57 However, substituting saline for nicotine does not decrease operant responding during the first sessions.23 Therefore, this would suggest that blocking the rewarding effects of nicotine does not immediately cause a decrease in operant responding. Additional studies need to be done to determine the cause of the discrepancies in studies with mecamylamine in humans and animals. One possible difference between the human and animal studies is that human smokers are highly nicotine dependent and that in most animal studies rats are only exposed to nicotine for 1 hour per day for several weeks.

In conclusion, the present studies indicate that females have a higher level of nicotine intake than males. Furthermore, the reinforcing properties of nicotine self-administration gradually increased over time. Despite that the females had a higher level of nicotine intake during the last five self-administration days, there were no sex differences in the reward-enhancing and stimulatory effects of nicotine self-administration.

Supplementary Material

A Contributorship Form detailing each author’s specific involvement with this content, as well as any supplementary data, are available online at https://academic.oup.com/ntr.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

Funding

This work was supported by a National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)/National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Tobacco Products (CTP) grant (DA042530) and NIDA grant (DA046411) to AB. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the FDA.

References

- 1. Baker TB, Brandon TH, Chassin L. Motivational influences on cigarette smoking. Annu Rev Psychol. 2004;55:463–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McNeill AD, Jarvis M, West R. Subjective effects of cigarette smoking in adolescents. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1987;92(1):115–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hughes JR, Higgins ST, Bickel WK. Nicotine withdrawal versus other drug withdrawal syndromes: similarities and dissimilarities. Addiction. 1994;89(11):1461–1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bruijnzeel AW. Tobacco addiction and the dysregulation of brain stress systems. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36(5):1418–1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Creamer MR, Wang TW, Babb S, et al. Tobacco product use and cessation indicators among adults—United States, 2018. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(45):1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: a report of the surgeon general. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cullen KA, Gentzke AS, Sawdey MD, et al. E-cigarette use among youth in the United States, 2019. JAMA. 2019;322(21):2095–2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tam J. E-cigarette, combustible, and smokeless tobacco product use combinations among youth in the United States, 2014–2019. Addict Behav. 2020;112:106636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Smith LC, Kallupi M, Tieu L, et al. Validation of a nicotine vapor self-administration model in rats with relevance to electronic cigarette use. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020;45(11):1909–1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harrison AA, Gasparini F, Markou A. Nicotine potentiation of brain stimulation reward reversed by DH beta E and SCH 23390, but not by eticlopride, LY 314582 or MPEP in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2002;160(1):56–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chellian R, Wilks I, Levin B, et al. Tobacco smoke exposure enhances reward sensitivity in male and female rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2021;238(3):845–855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Le Foll B, Goldberg SR. Nicotine induces conditioned place preferences over a large range of doses in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2005;178(4):481–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Igari M, Alexander JC, Ji Y, Qi X, Papke RL, Bruijnzeel AW. Varenicline and cytisine diminish the dysphoric-like state associated with spontaneous nicotine withdrawal in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39(2):455–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Caldarone BJ, King SL, Picciotto MR. Sex differences in anxiety-like behavior and locomotor activity following chronic nicotine exposure in mice. Neurosci Lett. 2008;439(2):187–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xue S, Behnood-Rod A, Wilson R, Wilks I, Tan S, Bruijnzeel AW. Rewarding effects of nicotine in adolescent and adult male and female rats as measured using intracranial self-stimulation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(2):172–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Torres OV, Natividad LA, Tejeda HA, Van Weelden SA, O’Dell LE. Female rats display dose-dependent differences to the rewarding and aversive effects of nicotine in an age-, hormone-, and sex-dependent manner. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2009;206(2):303–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lenoir M, Starosciak AK, Ledon J, et al. Sex differences in conditioned nicotine reward are age-specific. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2015;132:56–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Geste JR, Levin B, Wilks I, et al. Relationship between nicotine intake and reward function in rats with intermittent short versus long access to nicotine. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(2):213–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Paterson NE, Balfour DJ, Markou A. Chronic bupropion differentially alters the reinforcing, reward-enhancing and conditioned motivational properties of nicotine in rats. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(6):995–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kenny PJ, Chartoff E, Roberto M, Carlezon WA Jr, Markou A. NMDA receptors regulate nicotine-enhanced brain reward function and intravenous nicotine self-administration: role of the ventral tegmental area and central nucleus of the amygdala. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(2):266–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Marcinkiewcz CA, Prado MM, Isaac SK, Marshall A, Rylkova D, Bruijnzeel AW. Corticotropin-releasing factor within the central nucleus of the amygdala and the nucleus accumbens shell mediates the negative affective state of nicotine withdrawal in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(7):1743–1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bruijnzeel AW, Prado M, Isaac S. Corticotropin-releasing factor-1 receptor activation mediates nicotine withdrawal-induced deficit in brain reward function and stress-induced relapse. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66(2):110–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yamada H, Bruijnzeel AW. Stimulation of α2-adrenergic receptors in the central nucleus of the amygdala attenuates stress-induced reinstatement of nicotine seeking in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60(2–3):303–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Qi X, Yamada H, Corrie LW, et al. A critical role for the melanocortin 4 receptor in stress-induced relapse to nicotine seeking in rats. Addict Biol. 2015;20(2):324–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bruijnzeel AW, Markou A. Characterization of the effects of bupropion on the reinforcing properties of nicotine and food in rats. Synapse. 2003;50(1):20–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chellian R, Behnood-Rod A, Wilson R, et al. Adolescent nicotine and tobacco smoke exposure enhances nicotine self-administration in female rats. Neuropharmacology. 2020;176:108243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Qi X, Guzhva L, Yang Z, et al. Overexpression of CRF in the BNST diminishes dysphoria but not anxiety-like behavior in nicotine withdrawing rats. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;26(9):1378–1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kornetsky C, Esposito RU. Euphorigenic drugs: effects on the reward pathways of the brain. Fed Proc. 1979;38(11):2473–2476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bruijnzeel AW, Markou A. Adaptations in cholinergic transmission in the ventral tegmental area associated with the affective signs of nicotine withdrawal in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47(4):572–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liebman JM. Anxiety, anxiolytics and brain stimulation reinforcement. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1985;9(1):75–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chellian R, Wilson R, Polmann M, Knight P, Behnood-Rod A, Bruijnzeel AW. Evaluation of sex differences in the elasticity of demand for nicotine and food in rats. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(6):925–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dickinson A, Smith J, Mirenowicz J. Dissociation of Pavlovian and instrumental incentive learning under dopamine antagonists. Behav Neurosci. 2000;114(3):468–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Balleine B, Dickinson A. Signalling and incentive processes in instrumental reinforcer devaluation. Q J Exp Psychol B. 1992;45(4):285–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Balleine B. Instrumental performance following a shift in primary motivation depends on incentive learning. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 1992;18(3):236–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ball KT, Miller L, Sullivan C, et al. Effects of repeated yohimbine administration on reinstatement of palatable food seeking: involvement of dopamine D1 -like receptors and food-associated cues. Addict Biol. 2016;21(6):1140–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Beninger RJ, Cheng M, Hahn BL, et al. Effects of extinction, pimozide, SCH 23390, and metoclopramide on food-rewarded operant responding of rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1987;92(3):343–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Holtyn AF, Kaminski BJ, Wand GS, Weerts EM. Differences in extinction of cue‐maintained conditioned responses associated with self‐administration: alcohol versus a nonalcoholic reinforcer. Alcohol Clin Exp Res.. 2014;38(10):2639–2646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Caggiula AR, Donny EC, White AR, et al. Cue dependency of nicotine self-administration and smoking. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;70(4):515–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Davis WM, Smith SG. Role of conditioned reinforcers in the initiation, maintenance and extinction of drug-seeking behavior. Pavlov J Biol Sci. 1976;11(4):222–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Olsen CM, Winder DG. Operant sensation seeking engages similar neural substrates to operant drug seeking in C57 mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(7):1685–1694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Satanove DJ, Rahman S, Chan TV, Ren S, Clarke PB. Nicotine-induced enhancement of a sensory reinforcer in adult rats: antagonist pretreatment effects. Psychopharmacology. 2020;238(2):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Donny EC, Chaudhri N, Caggiula AR, et al. Operant responding for a visual reinforcer in rats is enhanced by noncontingent nicotine: implications for nicotine self-administration and reinforcement. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2003;169(1):68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chaudhri N, Caggiula AR, Donny EC, Palmatier MI, Liu X, Sved AF. Complex interactions between nicotine and nonpharmacological stimuli reveal multiple roles for nicotine in reinforcement. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2006;184(3–4):353–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Caggiula AR, Donny EC, White AR, et al. Environmental stimuli promote the acquisition of nicotine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2002;163(2):230–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lee AM, Calarco CA, McKee SA, Mineur YS, Picciotto MR. Variability in nicotine conditioned place preference and stress‐induced reinstatement in mice: effects of sex, initial chamber preference, and guanfacine. Genes, Brain Behav. 2019;19(3):e12601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kandel DB, Chen K. Extent of smoking and nicotine dependence in the United States: 1991–1993. Nicotine Tob Res. 2000;2(3):263–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. DeNoble VJ, Mele PC. Intravenous nicotine self-administration in rats: effects of mecamylamine, hexamethonium and naloxone. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2006;184(3–4):266–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Watkins SS, Epping-Jordan MP, Koob GF, Markou A. Blockade of nicotine self-administration with nicotinic antagonists in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;62(4):743–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Glick SD, Visker KE, Maisonneuve IM. An oral self-administration model of nicotine preference in rats: effects of mecamylamine. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1996;128(4):426–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kasten CR, Frazee AM, Boehm SL II. Developing a model of limited-access nicotine consumption in C57Bl/6J mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2016;148:28–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. McKee SA, Weinberger AH, Harrison EL, Coppola S, George TP. Effects of the nicotinic receptor antagonist mecamylamine on ad-lib smoking behavior, topography, and nicotine levels in smokers with and without schizophrenia: a preliminary study. Schizophr Res. 2009;115(2–3):317–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Nemeth-Coslett R, Henningfield JE, O’Keeffe MK, Griffiths RR. Effects of mecamylamine on human cigarette smoking and subjective ratings. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1986;88(4):420–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Stolerman IP, Goldfarb T, Fink R, Jarvik ME. Influencing cigarette smoking with nicotine antagonists. Psychopharmacologia. 1973;28(3):247–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rose JE, Behm FM, Westman EC. Acute effects of nicotine and mecamylamine on tobacco withdrawal symptoms, cigarette reward and ad lib smoking. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;68(2):187–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Grabus SD, Martin BR, Brown SE, Damaj MI. Nicotine place preference in the mouse: influences of prior handling, dose and strain and attenuation by nicotinic receptor antagonists. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2006;184(3–4):456–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Biala G, Staniak N, Budzynska B. Effects of varenicline and mecamylamine on the acquisition, expression, and reinstatement of nicotine-conditioned place preference by drug priming in rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2010;381(4):361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Corrigall WA, Coen KM. Nicotine maintains robust self-administration in rats on a limited-access schedule. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1989;99(4):473–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.