ABSTRACT

Alpha-galactosides or Raffinose Family Oligosaccharides (RFOs) are enriched in legumes and are considered as anti-nutritional factors responsible for inducing flatulence. Due to a lack of alpha-galactosidases in the stomachs of humans and other monogastric animals, these RFOs are not metabolized and are passed to the intestines to be processed by gut bacteria leading to distressing flatulence. In plants, alpha(α)-galactosides are involved in desiccation tolerance during seed maturation and act as a source of stored energy utilized by germinating seeds. The hydrolytic enzyme alpha-galactosidase (α-GAL) can break down RFOs into sucrose and galactose releasing the monosaccharide α-galactose back into the system. Through characterization of RFOs, sucrose, reducing sugars, and α-GAL activity in maturing and germinating chickpeas, we show that stored RFOs are likely required to maintain a steady-state level of reducing sugars. These reducing sugars can then be readily converted to generate energy required for the high energy-demanding germination process. Our observations indicate that RFO levels are lowest in imbibed seeds and rapidly increase post-imbibition. Both RFOs and the α-GAL activity are possibly required to maintain a steady-state level of the reducing monosaccharide sugars, starting from dry seeds all the way through post-germination, to provide the energy for increased germination vigor.

KEYWORDS: Alpha-galactosidase, chickpea, RFO, raffinose, Sucrose, Reducing sugar, flatulence

Introduction

One of the major complex sugars that accumulate in leguminous seeds are alpha (α)-galactosides, which are α-1,6-galactosyl derivatives of sucrose, better known as Raffinose Family Oligosaccharides (RFOs). RFOs accumulate in seeds as storage carbohydrates1 and one of the proposed roles of RFOs is to provide readily available energy for seed germination.2 While the necessity of RFOs for seed maturity, desiccation, and germination are currently under scrutiny, seed RFOs are considered as anti-nutritional constituents. Humans and other monogastric animals, do not possess the enzymes in their stomach to metabolize these RFOs, therefore allowing the unprocessed RFOs to be metabolized by the intestinal bacteria leading to distressing flatulence.3,4

Synthesis and accumulation of RFOs during seed maturation suggest a role for RFOs in establishing desiccation tolerance during the seed maturation process5–7 and imbibitional chilling.8 RFOs also participate in several other cellular functions including signal transduction,9,10 pathogen-induced wounding,11,12 and accumulate in vegetative tissues in response to a range of abiotic stresses.13–15

The substrates of RFO biosynthesis, galactinol and sucrose, accumulate during early stages of chickpea pod formation, while the products of RFO biosynthesis, raffinose and stachyose, accumulate during seed maturation with corresponding variation in the monosaccharide levels between the two stages indicating the synthesis of higher-order polymers during maturity.16 The activity of RFO biosynthetic enzymes, galactinol synthase, raffinose synthase, and stachyose synthase were found to be higher with increased accumulation of RFOs during seed maturity.16 The enzymes responsible for breaking down RFOs are the alpha(α)-galactosidases (EC 3.2.1.22) (α-GAL), which are glycoside hydrolases that hydrolyze the terminal α-D-galactosyl residues from RFOs, linear and branched-chain galactosyl-polysaccharides, and other commercial substrates.17 Following hydrolysis, the free D-galactose is converted to D-galactose-1-phosphate18,19 and further utilized by the conventional Leloir pathway or a pyrophosphorylase pathway to meet the energetic demands of germination.20 In tomato and peas, α-GAL is localized in different tissue types and expressed across different stages of plant development.21,22

In pea plants, inhibition of RFO breakdown mediated by α-GAL using 1-deoxygalactonojirimycin (DGJ) reduced seed germination to about 25% of the control, suggesting an obligatory role for RFOs in germination.23 Although soybean seed germination was delayed in the presence of DGJ,24 in stc1a (stachyose synthase) mutants, field emergence was similar to wild type,25 however, mips (myo-inositol phosphatase synthase) mutants which are compromised in myo-inositol production, showed reduced field emergence.26 Intriguingly, genotypes of soybean25 and chickpea16 with low RFO levels did not show the delayed germination phenotype suggesting that RFOs may be dispensable for seed germination.

Our focus in this study was to characterize the accumulation of RFOs and the associated α-GAL activity in maturing and germinating chickpea seeds given that chickpea is the second most cultivated legume for its carbohydrate, protein, dietary fibers, polyunsaturated fatty acids, minerals and vitamins.27 We have performed qualitative and quantitative measurements of α-GAL, RFOs, sucrose and reducing sugars during various stages of seed maturation and germination in chickpea to identify stages that accumulate the least amount of RFOs during seed germination.

Results

The major sequence of events during seed germination are, hormone-induced disruption of dormancy, abundant enzyme activity, initiation of embryo growth, and the resulting breach of the seed coat which is the physical barrier for the emergence of radicle and plumule. Oligosaccharides, especially α-galactosides, are utilized as an energy source during these physiological processes of germination. Therefore, we investigated the qualitative and quantitative role of α-GAL and the fate of the α-galactosides during seed germination in chickpea.

Chickpea seed germination indices indicate maximum requirement of energy during the early phase (24–48 h) of germination

In order to identify the precise phase during which maximum energy is required by the germinating chickpea seed, it is essential to characterize the seed germination time, germination rate and vigor. When dry Chickpeas (Desi type) were germinated following imbibition for 16 h, the mean germination time (MGT, the average length of time required for the maximum germination of the seed lot) was 2.13 days, while the mean germination rate (MGR, which indicates the frequency of germination) was 0.47 day−1. The coefficient of variation of germination time (CVt) was 22.7%. The coefficient of velocity of germination (CVG, an indicator of how fast the germination occurs) was 46.88%, while the uncertainty of germination (U) and synchronization (Z) were 0.47 and 0.84, respectively. These germination indices suggest that the seeds germination is synchronized with low U and higher CVG.

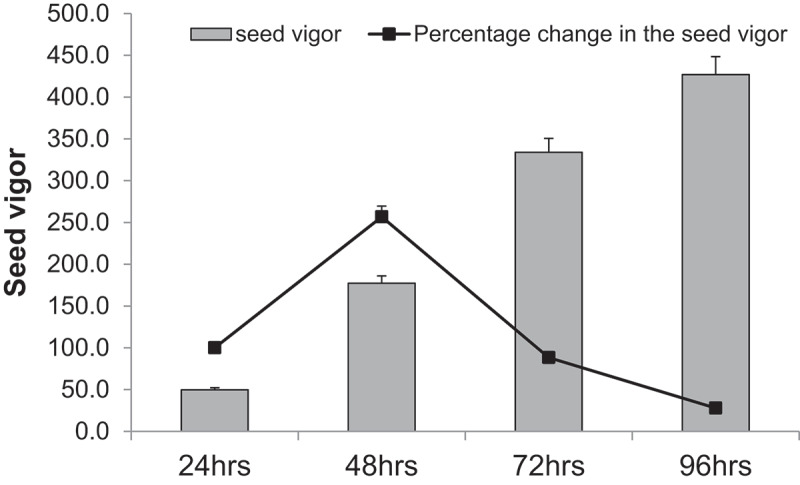

Germination vigor of chickpea seeds was then computed to assess the growth rate of the seedlings (Figure 1). The percent increase in seed germination vigor between 24 and 48 h of germination was the highest at 256.7, far greater than any other time point post-imbibition. This observation suggests that the release of dormancy, which is the trigger of biochemical and physiological cues of germination, occurs during the first phase (24 Hours After Imbibition (HAI)) and the maximum growth rate was observed during 48HAI. Therefore, 48HAI was the crucial stage in the germination of chickpea, as it is this stage the seed commits to sensu stricto germination.

Figure 1.

The seed vigor and the percent change in the vigor during various stages of seed germination is presented. The bars represent the vigor during various stages of germination and line graph represents the percent change in vigor during each germination stage.

Increased α-gal activity coincides with seed maturation and early germination

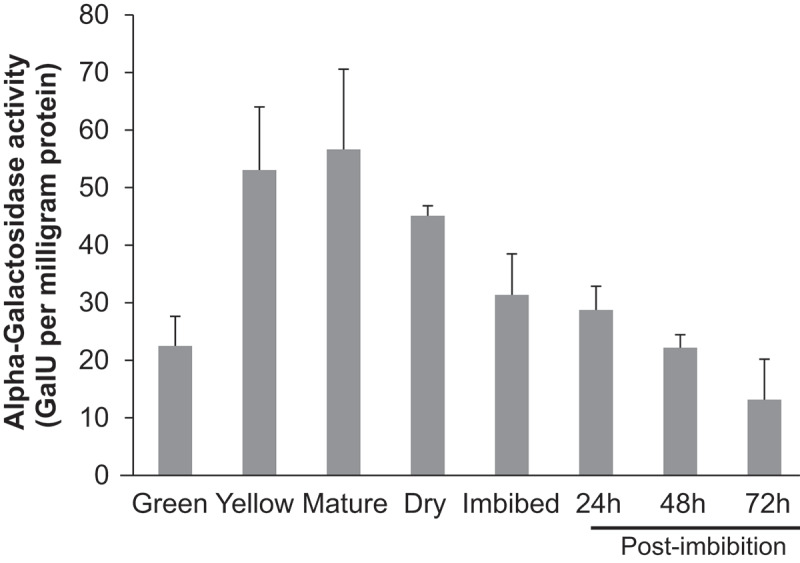

In dicots such as chickpea, most of the resources for the growing seedling prior to its ability to become photosynthetic are acquired from the cotyledons which are rich in proteins and sugars including RFOs. The enzyme responsible for processing RFOs into metabolizable sugars is α-galactosidase (α-GAL). To determine α-GAL activity during seed maturation and germination, seeds were collected at different stages and evaluated for α-GAL activity. The α-GAL activity (Gal Units/mg of protein) was significantly higher in the seeds from yellow and mature pods compared to all other stages (Figure 2). This was followed by very high α-GAL activity in dry seeds which was significantly down-regulated following imbibition and during germination (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Enzymatic assay of alpha-galactosidase during various stages of chickpea seed maturation and germination expressed as enzyme activity in GalU/milligram of protein. The data is a representation of n = 3, error bars represent standard error of mean.

Both sucrose and RFOs are consumed during seed germination

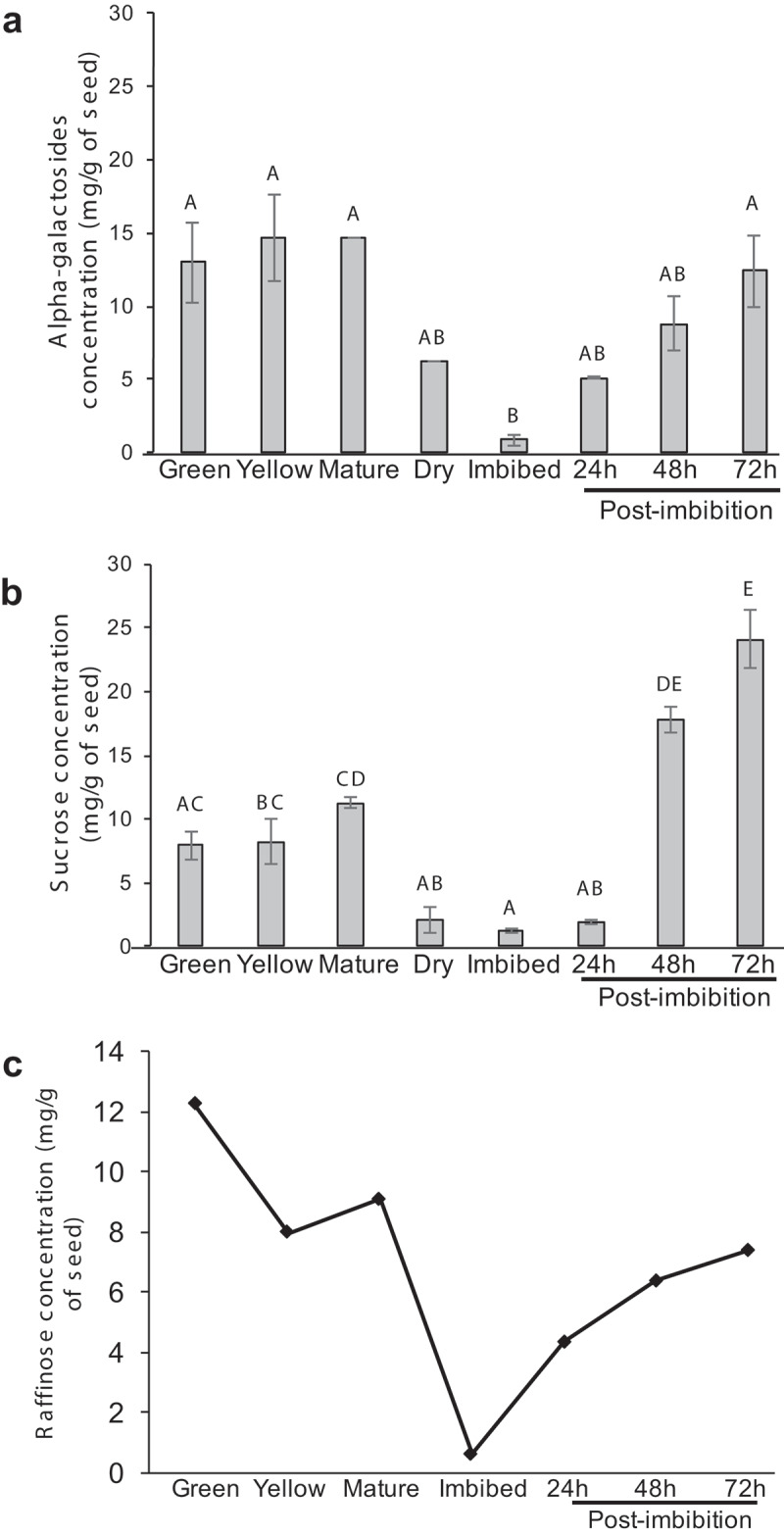

Based on the temporal pattern of α-GAL activity in seeds, we next investigated if this increased activity correlates with a change in RFO content. Since the major substrate of α-galactosidase in the seed is RFOs, we measured the seed α-galactosides, because external α-GAL can cleave the α-galactosidic linkages at the non-reducing ends of complex sugars, galactolipids (plant membranes) and galactomannan (plant cell walls).28 Therefore, the level of α-galactosides provides an indirect measure of RFO and other complex molecules that are modified with an α-galactosidic linkage. The level of α-galactosides or RFOs were significantly higher in seeds from green, yellow, mature pods, and dry seeds compared to the other stages and drastically decreased from 6.21mg/g in dry seed to 0.88 mg/g following imbibition, suggesting a breakdown of stored RFOs (Figure 3a). The increase in RFO levels post-imbibition suggests re-incorporation of free α-galactose into either cell membranes or cell walls of the growing shoot and root tips (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Estimation of α-galactosides (a) and sucrose (b) during various stages of chickpea seed maturation and germination. The sugars are expressed as milligram per gram of dry seed powder. The data represents three independent replicates, error bars indicate standard error of mean. Different letters over bars indicate significant differences based on Tukey’s multiple comparison analyses of the amount of sugars in various seed stages or phases of germination. (P < .05). (c) Estimation of raffinose through HPLC followed by mass spectrometry during various stages of chickpea seed maturation and germination. The data represents pooled samples from three biological replicates.

One of the major sugars in seeds that is immediately available as a source of energy is sucrose, which is readily translocated to the emerging shoot and root tips. Sucrose can easily be stored as raffinose by the addition of an α-galactosyl unit. An increase in α-GAL activity would therefore readily make sucrose available in the system. When sucrose content was measured in dry seeds and post-imbibition, sucrose content mimicked the RFO content with the highest amount of sucrose in green, yellow, mature pods and dry seeds with a drastic reduction during imbibition and a re-accumulation during germination (Figure 3b). The trend observed with the sugars was similar to the high α-GAL activity in the seeds from yellow, mature, and dry pod stages (Figure 2) where increased α-GAL activity is likely required to maintain a constant supply of monosaccharides for the energy requirements.

Raffinose content in seeds are the lowest following seed imbibition

Although RFOs represent the entire raffinose family of oligosaccharides, chickpea seeds are known to accumulate high amounts of raffinose, which is likely the reason for the flatulence experienced following consumption. To determine raffinose content in seeds during maturation and germination, the complex sugars were isolated and subjected to HPLC analysis (Supplemental Figure 1). The raffinose content in seeds displayed an accumulation pattern very similar to the total RFOs and sucrose, with higher amounts detected in the seeds from green pods and the lowest in the imbibed seeds (Figure 3a–c). This suggests that growing tissues immediately start accumulating sucrose and raffinose.

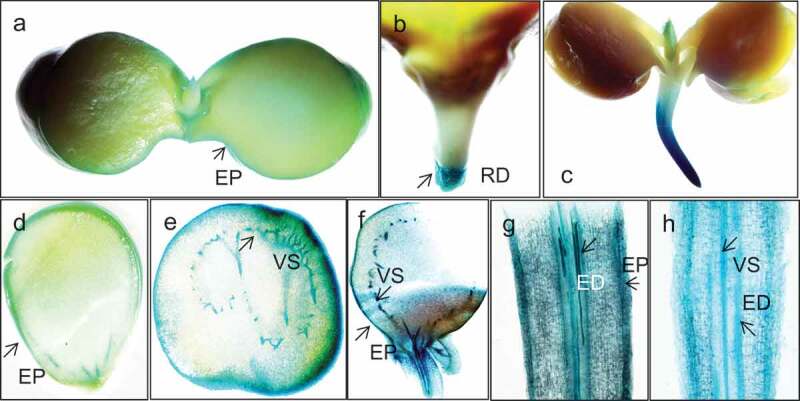

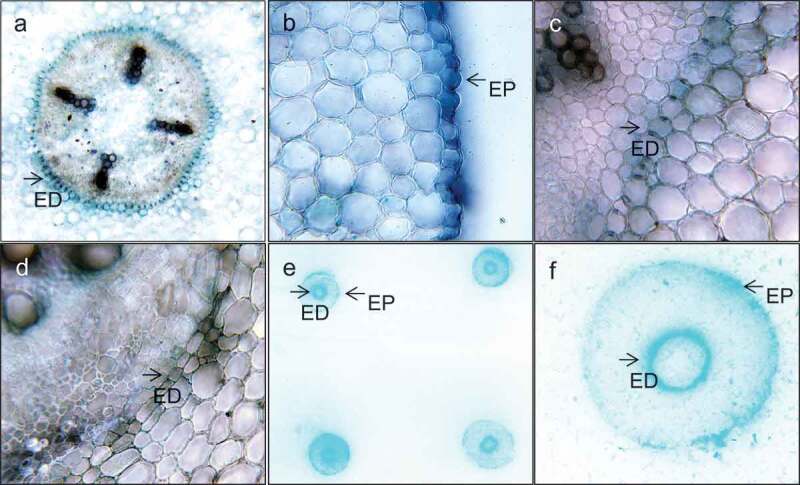

α-galactosidases are active in embryonic tissues during early germination phase

We next examined the spatial pattern of α-GAL activity in developing cotyledons through in situ activity assays. When various embryonic tissues were examined for α-GAL activity following imbibition, enzyme activity could be detected in the outer layers of the cotyledons and the root and shoot apices (Figure 4a–c). The enzyme was found to be active in the vasculature of the seeds from developing green pods and imbibed seed cotyledon sections (Figure 1d,e). In the sections of 16 h imbibed sprouts, the vasculature showed enzyme activity likely suggesting a role in the break-down of oligosaccharides to meet the energy demand at the growing tip (Figure 4e). Sections of the emerging root showed enzyme activity in the epidermis and endodermis (Figure 4f).

Figure 4.

Localization studies with hand sections of germinating chickpea seeds stained with X-alpha-gal for α-GAL activity. The epidermal layer of the dehusked seed showing α-GAL activity after 16 h of imbibition (a). The growing meristematic tips displaying α-GAL activity after 24HAI (b) and 48HAI (c). Hand section of the green pod (d), cotyledon of yellow pod (e), cotyledon of imbibed seed (f), and root 48HAI (g,h) showing α-GAL activity following staining with the substrate X- α-D-Gal. EP – epidermis, RD – radicle, ED – root endodermis, and VS – vascular tissue.

When sections of the developing roots were examined for α-GAL activity, the enzyme was active both in the epidermis of the root and in the Casparian strip of the endodermis of in vitro grown roots after 48 h of imbibition of the seeds. Tissue prints of the developing root sections also exhibited α-GAL activity both in the epidermis and endodermis (Figure 5e–f). However, α-GAL activity was undetected in the roots of older soil-grown plants (Figure 5d) suggesting a specific role for α-GAL during early seedling establishment. Based on the varied activity pattern, we believe that α-GAL could exist in multiple forms which can be temporally and spatially regulated.

Figure 5.

Localization studies with hand sections of chickpea seeds 48HAI stained with X-alpha-gal for α-GAL activity. α-GAL activity in root endodermis enclosing the stele (a), epidermal and endodermal root sections 48HAI (40X) (b & c), endodermis of soil-grown older root (40X) (d), and tissue prints of root cross sections on PVDF membrane and stained for α-GAL activity showing two concentric circles representing epidermis and endodermis of the root (e & f).

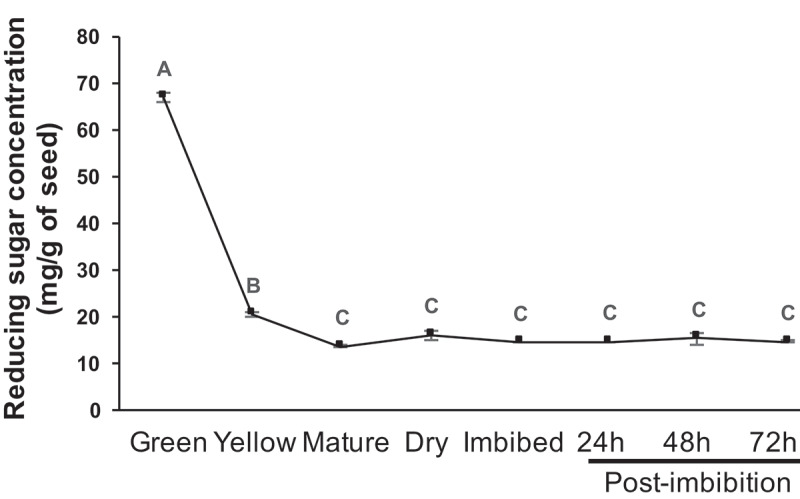

Reducing sugars remain constant from mature seeds to later germination phases

Typically during seed maturation, complex sugars are packed into the maturing seeds and following maturation, for immediate energy needs, a certain level of reducing sugars (monosaccharides) are maintained in the dry seeds. We predicted that the fluctuations observed in raffinose, RFOs and sucrose might be to maintain a steady supply of these monosaccharides for the energy requirements in the germinating seeds. Although these monosaccharides are essential, excess of these highly reactive reducing sugars could be detrimental to the system. To assess this, we estimated the steady-state level of reducing sugars throughout seed maturation and germination. As can be observed from Figure 6, the reducing sugars were quite high in the seeds from green pods where the sugars are loaded on to the bulking seed and this comes down by the time the pod is yellowing and beginning to mature (Figure 6, supplemental Figure 2). Interestingly, from yellow pods to post-germination stage, the reducing sugars were maintained at a constant level, suggesting a steady supply of reducing sugars for the energy needs of the seed that is drying out, equipping it for desiccation (dry seeds) and for germination (Figure 6, supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 6.

Steady-state level of reducing sugar concentration during various stages of chickpea seed maturation and germination. The sugars are expressed as milligram per gram of seed powder. The data represents three independent replicates, error bars indicate standard error of mean. Different letters over bars indicate significant differences based on Tukey’s multiple comparison analyses of the amount of reducing sugars in various seed stages or phases of germination. (P < .05).

Discussion

Our investigation reveals that α-galactosidase has a distinct spatial activity profile displaying strong activity in different tissue types (Figures 4 and 5). The enzyme activity was detected in the testa (cotyledon epidermis), cotyledon vasculature and had high activity near the growing tips, especially in root tissue. The increased accumulation of RFOs in the growing axes has been reported in tomato29 and other crops such as soybean, pea, and corn.30 The root apical meristem is an actively growing region with rapid cell wall biogenesis where the cell wall components are in constant rearrangement due to growth and expansion. Hand sections and tissue imprints of young roots showed cell-wall specific expression of α-galactosidase, typically in the root epidermis, root endodermis and in the Casparian strip (Figure 5), although this pattern was not observed in the older roots of soil-grown chickpea plants. This is the first report of expression of α-galactosidase in the Casparian strip of the root endodermis. It is known that the endodermal cells restructure their walls at distinct positions during the formation of the Casparian strip31 and α-galactosidases can enable constant availability of galactosyl units to restructure the cell-wall of the developing root. α-GAL therefore can participate in cell wall restructuring through cleaving galactosyl residues from linear or branched oligosaccharides and polysaccharides17 and through hydrolysis of cell-wall-associated galactomannan.32,33 The lack of epidermal and endodermal enzyme activity in the fully established soil-grown roots suggests a seedling-specific role for α-galactosidase in cell wall biogenesis in growing root zones.

Generally, the carbohydrate reserves are stored as polysaccharides and oligosaccharides, but in our study, we found abundant reserves in the form of sucrose in the dry seed (Figure 3b), an easily movable and metabolizable source of energy. When the seeds are imbibed, sucrose is a major source of energy, utilized during early stages of germination events, whose concentration drastically decreases during imbibition and later increases as the germination progresses (Figure 3b). Temporal profile of RFOs and raffinose in the seeds (Figure 3a,c) mimic the sucrose abundance, suggesting that RFOs are converted to sucrose to generate the metabolizable energy source. Imbibed seeds have been shown to maintain the ability to synthesize RFOs to replenish the RFO pool in the germinating seed,2 a trend we also observed with sucrose, RFOs and raffinose (Figure 3). It is interesting to note that there is a surge in the availability of sucrose 48 h post-imbibition, the stage where the germinating seed exhibits maximum seed vigor (Figure 1). This is also the stage where there was a significant increase in the availability of α-galactosides suggesting conversion of raffinose and RFOs into sucrose.

Therefore, it appears that both RFOs and sucrose act as a source of reserve energy for the germinating seeds. In peas, when α-galactosidase enzyme activity was blocked during germination, statistically significant difference in germination was observed between controls and α-GAL inhibited seeds.23 Germination experiments with soybean24 and pea23 in the presence of α-galactosidase inhibitor (DGJ) revealed a delay in the germination but did not terminate the process, indicating a supportive role of RFOs in seed germination by providing carbon and energy.22 A similar experiment with double knock-out mutants of raffinose synthase 4 and raffinose synthase 5 in Arabidopsis showed delayed germination in the dark.34 Therefore, a facilitator role rather than a regulatory role has been proposed for RFOs in germination,16 making RFOs dispensable for germination. In chickpea, the surge in the level of sucrose 48 h after imbibition corresponding to the concomitant activity of the α-GAL enzyme in the embryo and the active recycling of RFOs suggest that, commitment to germination is influenced by RFOs and α-GAL, while inhibition of the enzyme would delay germination time and affect seed vigor.

We observed that the level of steady-state reducing sugar concentration stayed constant from yellow seed to post-germination stage (Figure 6; supplemental Figure 2). This suggests that the highly reactive monosaccharides should be kept at a low level and how any fluctuations in the amount could become damaging to the system. Increased reducing sugar concentration in germinating seeds could contribute to enhanced production of hydroxyl radicals that could be damaging.35 Glycolysis has been shown to increase in the first 24 h of incubation during chickpea germination and declined thereafter, suggesting likely use of reducing sugars for increased glycolysis during the first 24 h.36 Glucose levels can also influence germination as optimum concentration of glucose is essential for seed germination, while above-optimal levels of glucose can delay the process of germination via ABA.37,38 Exogenous glucose has been shown delay germination in Arabidopsis39 and in rice40 by suppressing ABA breakdown.

Collectively, we have been able to show that RFOs and the concomitant α-GAL activity are controlled in a temporal fashion during seed maturity and germination. We propose that processing of RFOs contribute to maintaining a constant level of reducing sugars in the system, thereby promoting germination (supplemental Figure 2). We have also provided evidence that the flatulence-inducing RFOs and raffinose are at their lowest levels in chickpeas following imbibition due to their consumption during germination. This suggests that imbibition of chickpeas overnight could be one way reduce these compounds during cooking to reduce flatulence.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada grants.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Author Contributions

R.A, L.S, A.K, N.S, and V.M conducted the experiments, N.H performed the statistical analysis. R.A and M.A.S. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

References

- 1.Muzquiz M, Burbano C, Pedrosa MM, Folkman W, Gulewicz K.. Lupins as a potential source of raffinose family oligosaccharides: preparative method for their isolation and purification. Ind Crops Prod. 1999;9:1–7. doi: 10.1016/S0926-6690(98)00030-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peterbauer T, Richter A.. Biochemistry and physiology of raffinose family oligosaccharides and galactosyl cyclitols in seeds. Seed Sci Res. 2001;11:185–197. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salunkhe DK. Legumes in human nutrition: current status and future research needs. Curr Sci. 1982;51:387–394. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rackis JJ. Oligosaccharides of food legumes: alpha-galactosidase activity and the flatus problem. ACS Symp Ser Amer Chem Soc. 1975;15:207–222. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blackig M, Corbineau F, Grzesikit M, Guyi P, Côme D. Carbohydrate metabolism in the developing and maturing wheat embryo in relation to its desiccation tolerance. J Exp Bot. 1996;47:161–169. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Obendorf RL. Oligosaccharides and galactosyl cyclitols in seed desiccation tolerance. Seed Sci Res. 1997;7:63–74. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bailly C, Audigier C, Ladonne F, Wagner MH, Coste F, Corbineau F, Côme D. Changes in oligosaccharide content and antioxidant enzyme activities in developing bean seeds as related to acquisition of drying tolerance and seed quality. J Exp Bot. 2001;52:701–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Obendorf RL, Zimmerman AD, Ortiz PA, Taylor AG, Schnebly SR. Imbibitional chilling sensitivity and soluble carbohydrate composition of low raffinose, low stachyose soybean seed. Crop Sci. 2008;48:2396–2403. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevenson JM, Perera IY, Heilmann I, Persson S, Boss WF. Inositol signaling and plant growth. Trends Plant Sci. 2000;5:252–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xue H, Chen X, Li G. Involvement of phospholipid signaling in plant growth and hormone effects. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2007;10:483–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Couée I, Sulmon C, Gouesbet G, El Amrani A. Involvement of soluble sugars in reactive oxygen species balance and responses to oxidative stress in plants. J Exp Bot. 2006;57:449–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim MS, Cho SM, Kang EY, Im YJ, Hwangbo H, Kim YC, Ryu C-M, Yang KY, Chung GC, Cho BH. Galactinol is a signaling component of the induced systemic resistance caused by Pseudomonas chlororaphis O6 root colonization. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2008;21:1643–1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zuther E, Büchel K, Hundertmark M, Stitt M, Hincha DK, Heyer AG. The role of raffinose in the cold acclimation response of Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 2004;576:169–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zuther E, Schulz E, Childs LH, Hincha DK. Clinal variation in the non-acclimated and cold-acclimated freezing tolerance of Arabidopsis thaliana accessions. Plant Cell Environ. 2012;35:1860–1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peters S, Keller F. Frost tolerance in excised leaves of the common bugle (Ajuga reptans L.) correlates positively with the concentrations of raffinose family oligosaccharides (RFOs). Plant Cell Environ. 2009;32:1099–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gangola MP, Jaiswal S, Kannan U, Gaur PM, Båga M, Chibbar RN. Galactinol synthase enzyme activity influences raffinose family oligosaccharides (RFO) accumulation in developing chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). Seeds. Phytochemistry. 2016;125:88–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shabalin KA, Kulminskaya AA, Savel’ev AN, Shishlyannikov SM, Neustroev KN, Savel’ev AN, Shishlyannikov SM, Neustroev KN. Enzymatic properties of α-galactosidase from Trichoderma reesei in the hydrolysis of galactooligosaccharides. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2002;30:231–239. [Google Scholar]

- 18.PM DEY. Galactokinase of Vicia faba seeds. Eur J Biochem. 1983;136:155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan CP, Tugal HB, Baker A. Isolation of a cDNA encoding an Arabidopsis galactokinase by functional expression in yeast. Plant Mol Biol. 1997;34:497–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Main EL, Pharr DM, Huber SC, Moreland DE. Control of galactosyl-sugar metabolism in relation to rate of germination. Physiol Plant. 1983;59:387–392. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feurtado JA, Banik M, Bewley JD. The cloning and characterization of alpha-galactosidase present during and following germination of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) seed. J Exp Bot. 2001;52:1239–1249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blöchl A, Peterbauer T, Hofmann J, Richter A. Enzymatic breakdown of raffinose oligosaccharides in pea seeds. Planta. 2008;228:99–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blöchl A, Peterbauer T, Richter A. Inhibition of raffinose oligosaccharide breakdown delays germination of pea seeds. J Plant Physiol. 2007;164:1093–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dierking EC, Bilyeu KD. Raffinose and stachyose metabolism are not required for efficient soybean seed germination. J Plant Physiol. 2009;166:1329–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neus JD, Fehr WR, Schnebly SR. Agronomic and seed characteristics of soybean with reduced raffinose and stachyose. Crop Sci. 2005;45:589. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meis SJ, Fehr WR, Schnebly SR. Seed source effect on field emergence of soybean lines with reduced phytate and raffinose saccharides. Crop Sci. 2003;43:1336. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jukanti AK, Gaur PM, Gowda CLL, Chibbar RN. Nutritional quality and health benefits of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.): a review. Br J Nutr. 2012;108:S11–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jindou S, Karita S, Fujino E, Fujino T, Hayashi H, Kimura T, Sakka K, Ohmiya K. alpha-Galactosidase Aga27A, an enzymatic component of the Clostridium josui cellulosome. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:600–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gurusinghe S, Bradford KJ. Galactosyl-sucrose oligosaccharides and potential longevity of primed seeds. Seed Sci Res. 2001;11:121–134. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koster KL, Leopold AC. Sugars and Desiccation Tolerance in Seeds. Plant Physiol. 1988;88:829–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Somssich M, Khan GA, Persson S. Cell Wall Heterogeneity in Root Development of Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bewley JD. Breaking down the walls — a role for endo-β-mannanase in release from seed dormancy? Trends Plant Sci. 1997;2:464–469. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minic Z. Physiological roles of plant glycoside hydrolases. Planta. 2008;227:723–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gangl R, Tenhaken R. Raffinose family oligosaccharides Act as galactose stores in seeds and are required for rapid germination of arabidopsis in the dark. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Toorn P, McKersie BD. The high reducing sugar content during germination contributes to desiccation damage in lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) radicles. Seed Sci Res. 1995;5:145–149. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Botha FC, Potgieter GP, Botha AM. Respiratory metabolism and gene expression during seed germination. Plant Growth Regul. 1992;11:211–224. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hsu Y-F, Chen Y-C, Hsiao Y-C, Wang B-J, Lin S-Y, Cheng W-H, Jauh G-Y, Harada JJ, Wang C-S. AtRH57, a DEAD-box RNA helicase, is involved in feedback inhibition of glucose-mediated abscisic acid accumulation during seedling development and additively affects pre-ribosomal RNA processing with high glucose. Plant J. 2014;77:119–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yuan K, Wysocka-Diller J. Phytohormone signalling pathways interact with sugars during seed germination and seedling development. J Exp Bot. 2006;57:3359–3367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Price J, Li T-C, Kang SG, Na JK, Jang J-C. Mechanisms of glucose signaling during germination of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:1424–1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu G, Ye N, Zhang J. Glucose-induced delay of seed germination in rice is mediated by the suppression of ABA catabolism rather than an enhancement of ABA biosynthesis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009;50:644–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.