Abstract

Evaluation of drought is essential and useful to eradicate climate change impact. Therefore, this study aims to explore the spatiotemporal drought intensity trend in seven climatic zones of Bangladesh during 1979–2019. Mann-Kendall trend test and Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) are employed to identify drought trend and status, whereas spatial visualization is checked through Inverse Distance Weighting Interpolation. The study's findings emphasize the decreasing rate of SPEI in all climatic zones except the south-eastern zone, which is > 0.0065, >0.007, >0.0128, and >-0.0001 for SPEI 09 12, 24, and 06, respectively. Furthermore, the northern region has the highest value in SPEI in some periods with the highest decrease rate in SPEI 06, SPEI 09, SPEI 12 demonstrates greater drought responsibilities. The Barisal (.>-3.75), Rangpur (>-3.65), Dinajpur ((>-3.00), Rajshahi (>-4.35), Bogra (>-4.50), Ishurdi (>-3.45), Faridpur (>-4.30) and Madaripur (>-2.10) found under extreme drought-prone climatic zone. Thus, the study recommends taking initiatives and management for water resources to adopt mitigation planning for drought-prone climatic zones.

Keywords: Drought, Trend, SPEI, Climatic zone, Bangladesh

drought; trend; SPEI; climatic zone; Bangladesh

1. Introduction

Drought is a naturally recurring phenomenon that causes a reduction of water availability with inadequate rainfall. As a result of inadequate evaporative and transpiratory processes, drought significantly influences all climatic zones (Mishra and Singh, 2010; Pal et al., 2000). Droughts are defined as water shortages that endure for months or years and are accompanied by lower-than-normal rainfall (Bae et al., 2018). Based on a different study when rainfall deficit is more than 25 or 30 percent, it is considered drought (CWC, 1996; Venkateswarlu, 1992). Drought consists of subversive impacts on irrigation, the environment, and society. Rainfall variability and temperature rise are caused by climate change, while drought has increased in various parts of the world (Habiba et al., 2013a; IPCC, 2007). As a result of global warming, Bangladesh is the most vulnerable country to climate change, with temperatures rising in recent decades. This could lead to water scarcity and drought dominance in the future decades (Rahman and Lateh, 2017; Uddin et al., 2020).

Global perspective demonstrates drought is the second most devastative disaster (Nagarajan, 2010). Bangladesh is considered a drought-prone country, including floods, cyclones, and coastal erosion. The country is also experienced several historical droughts in the year of 1951, 1957, 1958, 1961, 1966, 1972 and 1979 which covers total land area of 31.63%, 46.54%, 37.47%, 22.39%, 18.42%, 42.48% and 42.04% respectively (Banglapedia, 2014c). Drought influenced the reduction of crop production by 25–30% (Habiba et al., 2013a), whereas 53% of people live in Bangladesh's drought-prone areas (Ahmed, 2006). However, extensive irrigation practice continues in several parts of the country, requiring a demand for water and future availability that may conclude with food security. Several studies indicate the loss of agriculture, life, and property due to drought is more than flood consequences; less attention is paid to this phenomenon (Alexander, 1995; Rahman and Saha, 2007; Shahid and Behrawan, 2008; WBB, 1998). Therefore, a detailed investigation is urgently needed for minimizing potential risk drought severity in Bangladesh.

Trend analysis can detect the effect of climate change scenarios on the provided variable of hydroclimatic variabilities (Nourani et al., 2018). Protracted changes in hydro climatological factors (variations) have been shown to alter the deliverable, geographical, and spatiotemporal variability of air and water in a region (Danandeh Mehr and Nourani, 2017). Several methods were applied for drought analysis in various studies among them meteorological data based Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) and the Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI) are most common; however, SPEI is a new method, but it fulfills proper data utilization (McKee et al., 1993; Palmer, 1965). Also, wavelet trans-form Mann–Kendall (WTMK) is also used as a recent method of hydroclimatic statistics (Danandeh Mehr et al., 2013; Nourani et al., 2015). In a recent article, the new approaches of innovative trend analysis (ITA) and sequential average methodology (SAM) were also employed in conjunction with the optimization of the Mann-Kendall (MK) test and Sen's Slope estimator for trend analysis on different geological timescales (Danandeh Mehr et al., 2021; Jerin et al., 2021). Therefore, the Mann-Kendall test has been the most extensively used approach because it is easy to evaluate and does not reflect any particular summary statistics (Mehr and Vaheddoost, 2019). Also, SPEI is the combined analysis of PDSI and SPI, which signifies its analytical strategy which needs to be implemented in the study area (Wang et al., 2017). Throughout the age of climate extreme weather events, flood and drought occurrence trends are crucial for protracted river basin management, agriculture and fisheries, and crisis response in Bangladesh.

Several drought assessments have been conducted in Bangladesh (Hoque et al., 2020; Kamruzzaman et al., 2019; Shahid and Behrawan, 2008). Zinat et al. (2020) explored SPEI and MK test for BORO rice growing capacities with only eight stations. Rahman et al. (2017) studied drought impacts on groundwater table by utilizing SPI and MK test in the Brand area of Bangladesh from 1971-2011. More recently Mondol et al. (2021) identified meteorological drought for the north Bengal of Bangladesh. However, most of the study focused on the drought assessment of the whole Bangladesh in part. Other study focused on ground water drought in North (Shahid and Hazarika, 2010), mitigation strategy of farmers during drought occurrences (Habiba et al., 2012), characteristics of dry periods (Dash et al., 2012). Therefore no study focused historical drought intensity assessment considering climatic region in Bangladesh. However, the climatic region contained vast importance on quantification of reference evapotranspiration (Salam et al., 2020), farmland value (Shakhawat Hossain et al., 2020), crop farming and climate change vulnerabilities (Hossain et al., 2019). Also, the existing literature does not emphasize drought intensity despite evaluating only drought frequency, agricultural drought severity, and parametric analysis for seasonal variation (Alamgir et al., 2019; Dash et al., 2012; Kamruzzaman et al., 2019). To fill these gaps, this study focuses on dry periods intensity change trends in seven climatic zones in Bangladesh with the spatial distribution of drought severity. Thus, this study aims to identify the specific dry periods trends in Bangladesh's seven climatic zone with spatiotemporal evaluation. To the best of the author's knowledge, this is the first study of drought assessment that exploits seven climatic zones.

The scope of the study is limited to recent datasets (1979–2019) and methodological illustration of SPEI, MK and IDW approach employed in the research. The duration of dataset could be extended if methodological advancement is implemented for missing values before 1979. However, we expect this investigation could bring vital significance to vulnerable drought-prone area identification based on zonation and mitigation; drought management response could also be assigned through this study. This study examines recent datasets of monthly rainfall, focused on the spatiotemporal exploration of dry periods changes by calculating SPEI and MK test (Kendall, 1975; Mann, 1945; McKee et al., 1993; Palmer, 1965). An index of drought differentiation contained seven classes have been used for quantifying severity in seven climatic regions. Also, spatial pattern of dry period occurrence is performed through IDW techniques (Shepard, 1968).

2. Data and methods

2.1. Study area

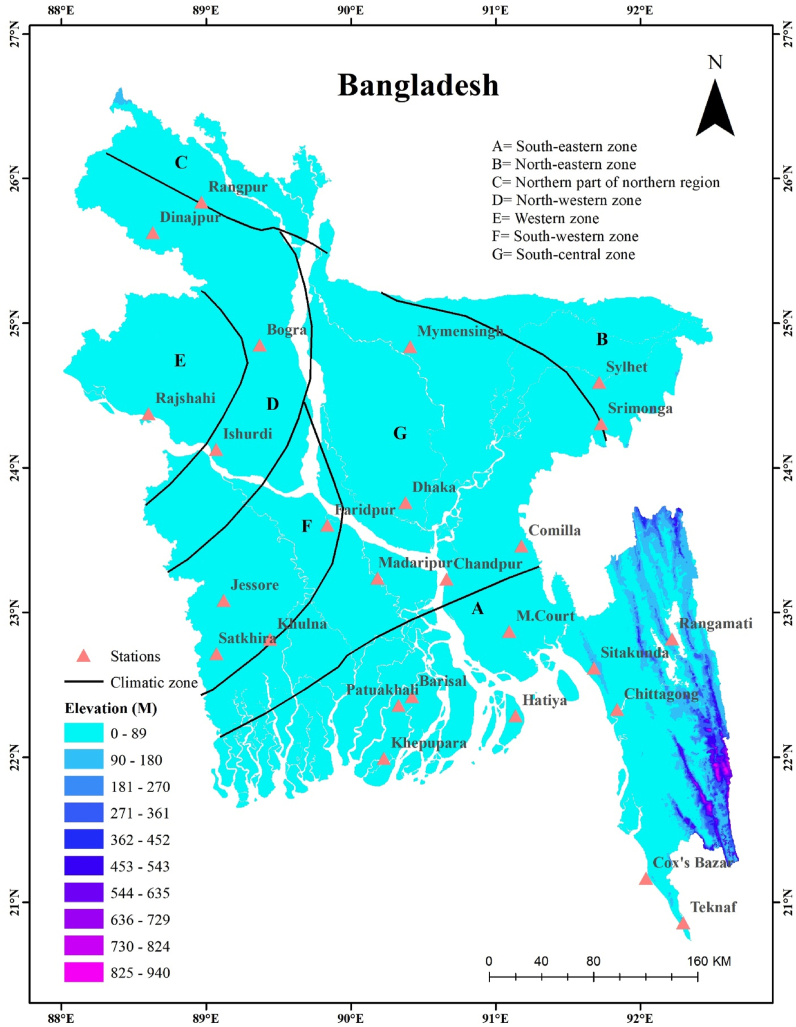

The absolute geographical location of Bangladesh defines the location of 20°34′ N – 26°38′ N latitude to 88°01′ E– 92°41′ E longitude with an area of 147570 sq km. The country is consisting extremely flat regions except for hilly areas in the southeast and southwest (Figure 1). The region experiences winter (December to February), pre-monsoon (March to May), monsoon (June to September), and the -post-monsoon (October to November) season (Banglapedia, 2014b). The influential climatic character of Bangladesh could be divided in seven climatic regions namely south-eastern region(A), north-eastern region(B), northern part of northern region(C), north-western region(D), western region(E), south-western region(F), south-central region (G), (Figure 1) (Banglapedia, 2014a). The country's average mean annual rainfall is 2428 mm, the maximum temperature is 30 °C–40 °C, and the minimum temperature is observed 5.2 °C–10 °C (BMD, 2013). Therefore monsoon season gets more than 80% precipitation, the hottest and coldest season is found for summer and winter (January) respectively (Islam et al., 2018; Rahman and Islam, 2019).

Figure 1.

Digital elevation model of the study area.

2.2. Data acquisition and pre-processing

Monthly rainfall and temperature data are needed to calculate the Mann-Kendall trend test and Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) calculation, which were collected from Bangladesh Agricultural Research Council (BARC). For this study, we considered a recent dataset for twenty-six climatic stations among the total of 35 stations used from 1979 to 2019, where no missing data were found (Table 1) although several studies signify that less than 2 per cent of missing data is adequate to analyze the rainfall records (Shahid, 2008; Towfiqul Islam et al., 2020; Mortuza et al., 2019). Such selected stations have proven data integrity for long-term hydro-climatic measurements (Mondol et al., 2021; Mortuza et al., 2019). To avoid biases and maintain data quality, the other nine stations are excluded as those stations are newly established and do not contain more extended period dataset (Towfiqul Islam et al., 2020) containing 6 to 22 percent missing values on average (Shahid, 2008), which include stations Ambagan (1979–2019), Bhola (1979), Chuadanga (1979–2002), Mongla (1979–1998), Syedpur (1979–2002), Tangail (1979–1986), Feni (2001), Kutubdia (1979–1986), Sandwip (2003). Additionally, the von Neumann ratio, standard normal homogeneity test, and range test were used to determine homogeneity, where all datasets being found to be homogeneous (Alexandersson, 1986; Buishand, 1982; von Neumann, 1941). Furthermore, we have illustrated the spatial distribution where IDW was used in ArcMap 10.8.

Table 1.

Monthly rainfall and temperature statistics from 26 meteorological stations (1979–2019), including WMO code, latitude, longitude, elevation, temperature, precipitation, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis.

| Stations | WMO Code |

Lat(N) | Lon(E) | Elevation (m) | Mean |

Std. Deviation |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rainfall | Temp. (0C) | Rainfall | Temp. | Rainfall | Temp. | Rainfall | Temp. | |||||

| Teknaf | 41998 | 23.43 | 91.18 | 06 | 4123.51 | 26.22 | 831.57 | 0.32 | -1.94 | 0.38 | 6.21 | -0.72 |

| Sylhet | 41891 | 22.72 | 90.37 | 35 | 4089 | 25.42 | 681.11 | 0.57 | 0.76 | 0.03 | 0.19 | -0.96 |

| Srimangal | 41915 | 24.30 | 91.73 | 23 | 2372.37 | 25.12 | 450.02 | 0.32 | 1.14 | 0.52 | 1.31 | 0.38 |

| Sitakunda | 41965 | 23.23 | 90.7 | 10 | 3028.9 | 25.90 | 823.15 | 0.39 | -0.87 | -0.04 | 2.47 | -0.49 |

| Satkhira | 41946 | 22. 43 | 89. 40 | 06 | 1699.76 | 26.53 | 262.33 | 0.34 | -0.24 | -0.07 | -1.04 | 0.28 |

| Rangpur | 41859 | 24.73 | 90.42 | 34 | 2244.9 | 24.92 | 474.14 | 0.38 | 0.76 | -0.47 | 1.49 | 0.77 |

| Rangamati | 41966 | 23.2 | 89.33 | 63 | 2577.17 | 25.87 | 525.51 | 0.38 | 0.49 | -0.41 | -0.02 | -0.14 |

| Rajhshahi | 41895 | 22.72 | 89.08 | 20 | 1422.9 | 25.91 | 293.86 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.40 | 0.94 | 0.15 |

| Patuakhali | 41960 | 23.6 | 89.85 | 03 | 2469.95 | 26.40 | 603.50 | 0.33 | -1.12 | 0.34 | 2.91 | 0.13 |

| Mymensigh | 41886 | 24.15 | 89.03 | 19 | 2225.51 | 25.41 | 503.43 | 0.34 | 0.05 | -0.57 | 0.12 | 1.30 |

| Madaripur | 41939 | 24.37 | 88.7 | 13 | 1925.17 | 26.21 | 353.60 | 0.29 | -0.02 | -0.12 | 0.01 | 0.07 |

| M.court | 41953 | 22.52 | 91.06 | 06 | 3099.51 | 26.16 | 532.79 | 0.50 | 0.86 | -0.48 | 1.76 | 0.02 |

| Khulna | 41947 | 24.85 | 89.37 | 04 | 1837.07 | 26.55 | 357.19 | 0.41 | -0.24 | -0.16 | -0.22 | -0.15 |

| Khepupara | 41984 | 21.59 | 90.13 | 09 | 2716.05 | 26.34 | 549.50 | 0.31 | -1.40 | 0.03 | 2.43 | 0.74 |

| Jashore | 41936 | 25.73 | 89.27 | 07 | 1677.76 | 26.36 | 319.16 | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.23 | -0.66 | 0.23 |

| Ishurdi | 41907 | 24.15 | 89.05 | 14 | 1489.85 | 25.82 | 294.05 | 0.34 | 0.26 | 0.29 | -0.04 | 0.46 |

| Hatiya | 41963 | 22.40 | 91.00 | 04 | 3202.07 | 25.93 | 660.97 | 0.35 | -1.45 | 0.17 | 5.92 | -0.68 |

| Faridpur | 41923 | 24.9 | 91.88 | 09 | 1788.73 | 26.06 | 347.31 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.21 | -0.61 | 0.05 |

| Dinajpur | 41863 | 25.38 | 88.38 | 37 | 1937.37 | 25.07 | 464.08 | 0.32 | 0.42 | -0.13 | 0.72 | -0.05 |

| Dhaka | 41923 | 23.03 | 91.42 | 09 | 2045.95 | 26.37 | 468.62 | 0.42 | 0.33 | 0.14 | -0.57 | -0.57 |

| Cox's Bazar | 41992 | 21.98 | 90.68 | 04 | 3608.93 | 26.52 | 783.30 | 0.47 | -1.60 | -0.11 | 4.10 | -0.94 |

| Comilla | 41933 | 22.33 | 90.33 | 10 | 2063.37 | 25.71 | 403.70 | 0.37 | 0.44 | 0.01 | 0.65 | 0.12 |

| Chittagong | 41977 | 22.19 | 91.50 | 34 | 2964.29 | 26.17 | 494.20 | 0.46 | 0.65 | 0.15 | 0.10 | -0.90 |

| Chandpur | 41941 | 23.13 | 90.39 | 07 | 2157.24 | 26.21 | 550.13 | 0.47 | 0.95 | -0.44 | 0.90 | 1.33 |

| Bogra | 41883 | 21.45 | 91.96 | 20 | 1747.41 | 25.90 | 387.03 | 0.33 | 0.06 | 0.49 | -0.84 | 0.12 |

| Barisal | 41950 | 22.68 | 90.65 | 04 | 2084.9 | 26.04 | 361.12 | 0.36 | -0.01 | 0.53 | -0.82 | 0.28 |

2.3. Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI)

SPEI is an extended method for Standardized precipitation index (SPI) which calculate the drought status with the help of precipitation data and potential evapotranspiration (PET) data where SPI only uses the precipitation data (Mengyao Guo, 2018; Mohsenipour et al., 2018; Vicente-Serrano and Sergio, 2015). The PDSI was among the first methods to successfully estimate the magnitude of droughts in various environmental conditions (Palmer, 1965). However, it lacks efficiency on extreme variations of precipitation (Burke et al., 2006). Furthermore, SPI contains the absence of hydrologic balance, which was solely used to account for data-limited locations for individual purposes (Wang et al., 2017). To avoid these methodological omissions, we employed SPEI as it incorporates the PDSI's reactivity to variations in evaporation requirement due to temperature oscillations and patterns with simplified computations of SPI (Vicente-Serrano, 2006). SPEI also offers several benefits, such as being identical towards the SPI and even being determined across various time frames to evaluate meteorological drought, including length, origin, magnitude, severity and accomplishment (Wang et al., 2017). SPEI was used by Miah et al. (2017) to identify local drought variance over our research area. In our study area, Uddin et al. (2020) identified SPEI as being superior to SPI. We performed SPEI 03, SPEI 06, SPEI 09, SPEI 12, and SPEI 24 to observe drought possibilities and differences on temporal purposes. In addition, SPEI 03 represents the seasonal or short time drought conditions (WANG et al., 2018), SPEI 06 and SPEI 09 represents the long-time drought characteristics (Mengyao Guo, 2018), SPEI 12 reflects the interannual variation of drought (Wang et al., 2018) and SPEI 24 represents the most extended time drought characteristics. For calculating the SPEI, the algorithm and process developed by (Vicente-Serrano et al., 2010) were used in this study which documentation and executable files are available in http://hdl.handle.net/10261/10002 (Potop et al., 2014; Tong et al., 2017). This software requires creating a particular dataset, a complete dataset was created for twenty-six stations to calculate the SPEI values. SPEI parameters (Danandeh Mehr et al., 2020), which represent the wet and dry periods in an area, are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Parameters of SPEI.

| Category | SPEI |

|---|---|

| Extreme drought | −1.83 and less |

| Severe drought | −1.82 to −1.43 |

| Moderate drought | −1.42 to −1.49 |

| Near normal | -1.0 to 1.0 |

| Moderate wet | 1.42 to <1.0 |

| Severely wet | 1.82 to <1.43 |

| Extremely wet | 1.83 and above |

2.4. Mann-Kendall trend test

The Mann-Kendall test (Kendall, 1975; Mann, 1945) is used for determining whether a time series has a trend or not, which can be an upward or downward trend. The significance of trends can be classified into 90%, 95%, and 99% confidence level thresholds. In this study, we used a 95% confidence level for all results. No autocorrelation in data is required, neither does the data need to be distributed normally or linearly (Milan and Slavisa, 2013). This is widely used as a nonparametric test worldwide. For statistic S calculated with the following Eq. (1) (Kabanda, 2018; Meena et al., 2019; Mohsenipour et al., 2018; Rahman et al., 2017; Sharma and Singh, 2017; Wang et al., 2020)

| (1) |

where data points are xi and xj and data values are in i and j (j > i), where ) is determined by Eq. (2)

| (2) |

The variance of S is determined by Eq. (3)

| (3) |

where n represent the data points, t differs across the tied ranks, and ft is the number of rank t occurrence.

The following Eq. (4) is for calculating the standard normal test statistic Z

| (4) |

The positive value of Z represents the upward trend, where the negative value means the downward trend. There is no trend in the null hypothesis for this trend; however, the alternative hypothesis is a trend inside the two-sided test or an upward trend (or downward trend) inside the one-sided test (Milan and Slavisa, 2013). This study was developed with a 95% confidence level, so the null hypothesis was rejected if |Z|>1.96. The documentation and the tools which were used for the calculation MK trend test are available in https://www.real-statistics.com/time-series-analysis/time-series-miscellaneous/mann-kendall-test/.

2.5. Inverse Distance Weighting Interpolation

As a prevalent and simplistic interpolation method, Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW) was used for this study (Shepard, 1968; Adhikary et al., 2017; Amini et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2017; Das, 2019). This method is frequently used to determine unknown hydrological or geographic details. This method states that every measurement origin has a local effect that decreases with distance. The impact of a deliberate point is weighted from an examined highlight, an inexact point according to the distance. Following the IDW method formula,

| (5) |

here, is the interpolated value at point S0, Z is the observed value at a point , n represents the number of observations, and is the weight. The weights can be calculated by Eq. (6)

| (6) |

here, p represents power and is the distance between a target and observations.

3. Results

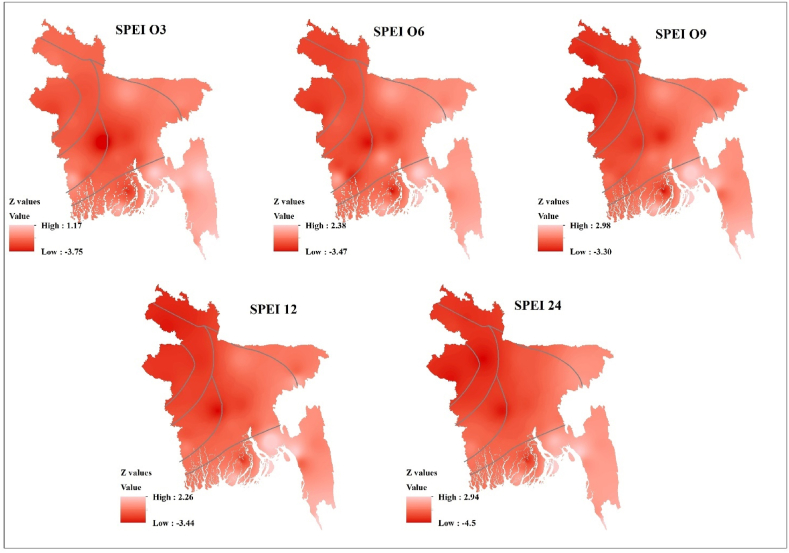

3.1. SPEI variability and spatial distribution

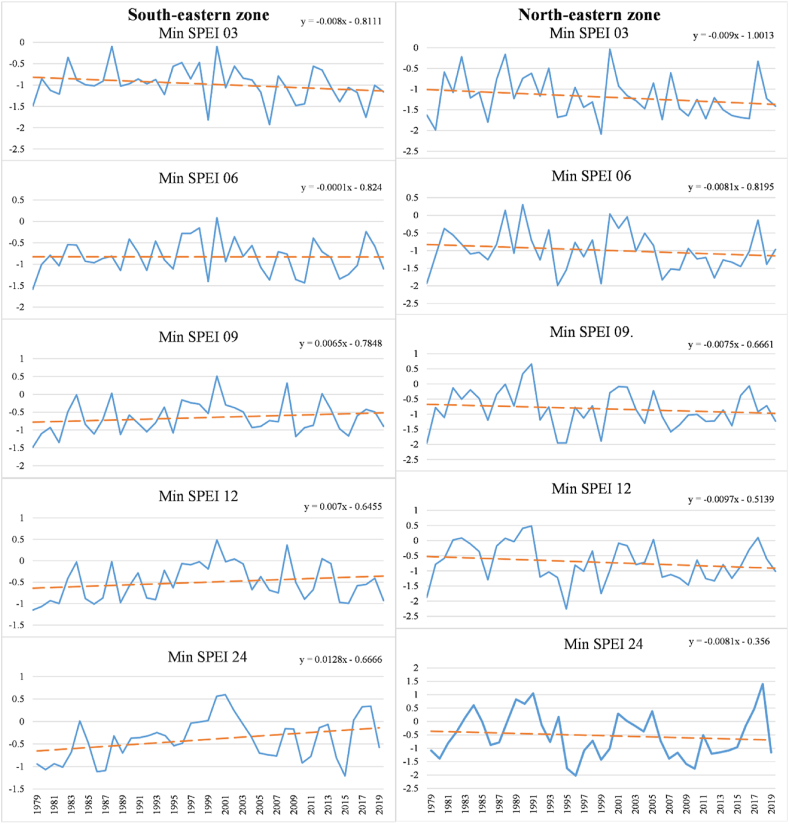

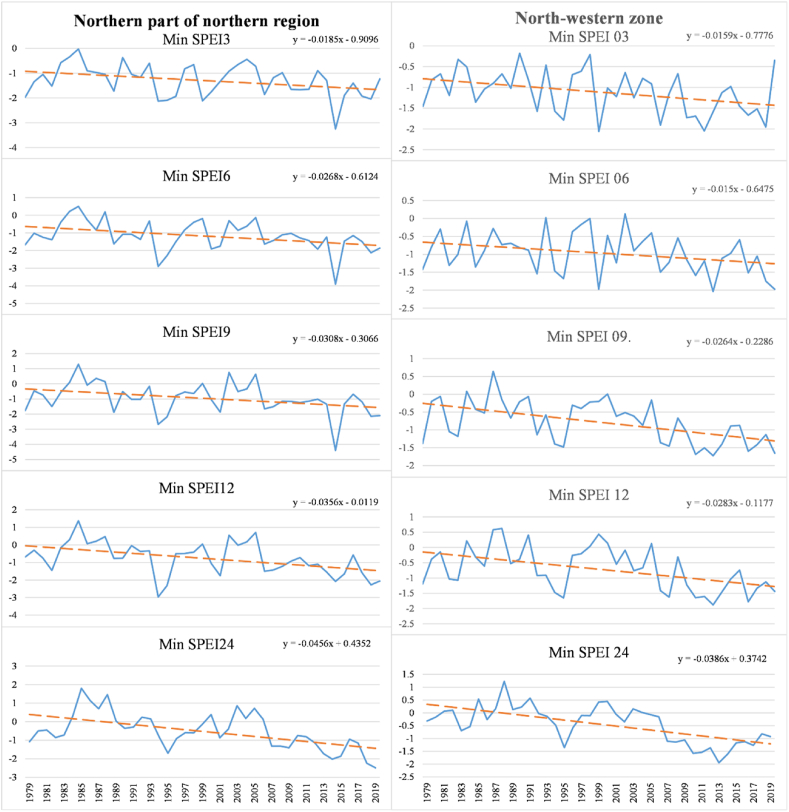

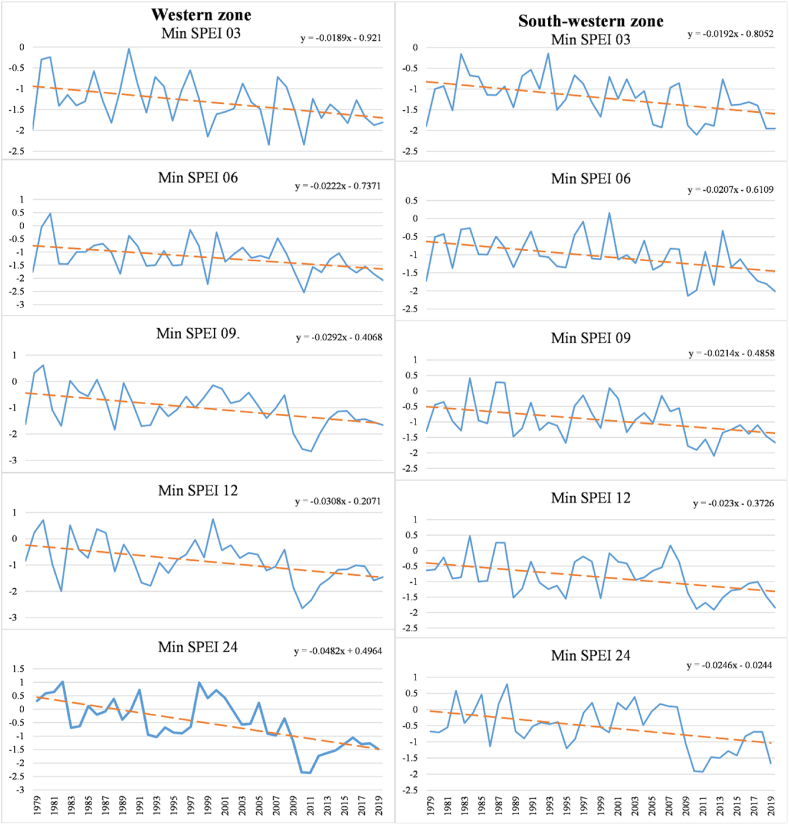

Standardized Precipitation Evaporation Index (SPEI) quantifies the condition of droughts through monitoring the combined effects of temperature and precipitation. The Mann- Kendall test analyzes seven climatic regions of Bangladesh to identify the SPEI intensity trend. From the period of 1979–2019, the appearance of drought is computed in SPEI 03, SPEI 06, SPEI 09, SPEI 12, and SPEI 24 in 26 stations to assess and analyze the meteorological drought of the study area. For calculating the SPEI result zone-wise, the station's results in the same zone, were averaged and the highest minimum SPEI value is displayed in (Figures 2, 3, 4, and 5). Table 3 MK test elucidates upward trends (Z parametric more than 1.96) and downward trends (Z parameter less than -1.96). Z values of all stations were used for creating the spatial distribution.

Figure 2.

Average minimum SPEI in South-eastern zone and North-eastern zone in the time period of 1979–2019.

Figure 3.

Average minimum SPEI of Northern part of the northern region and North-western zone in the time period of 1979–2019.

Figure 4.

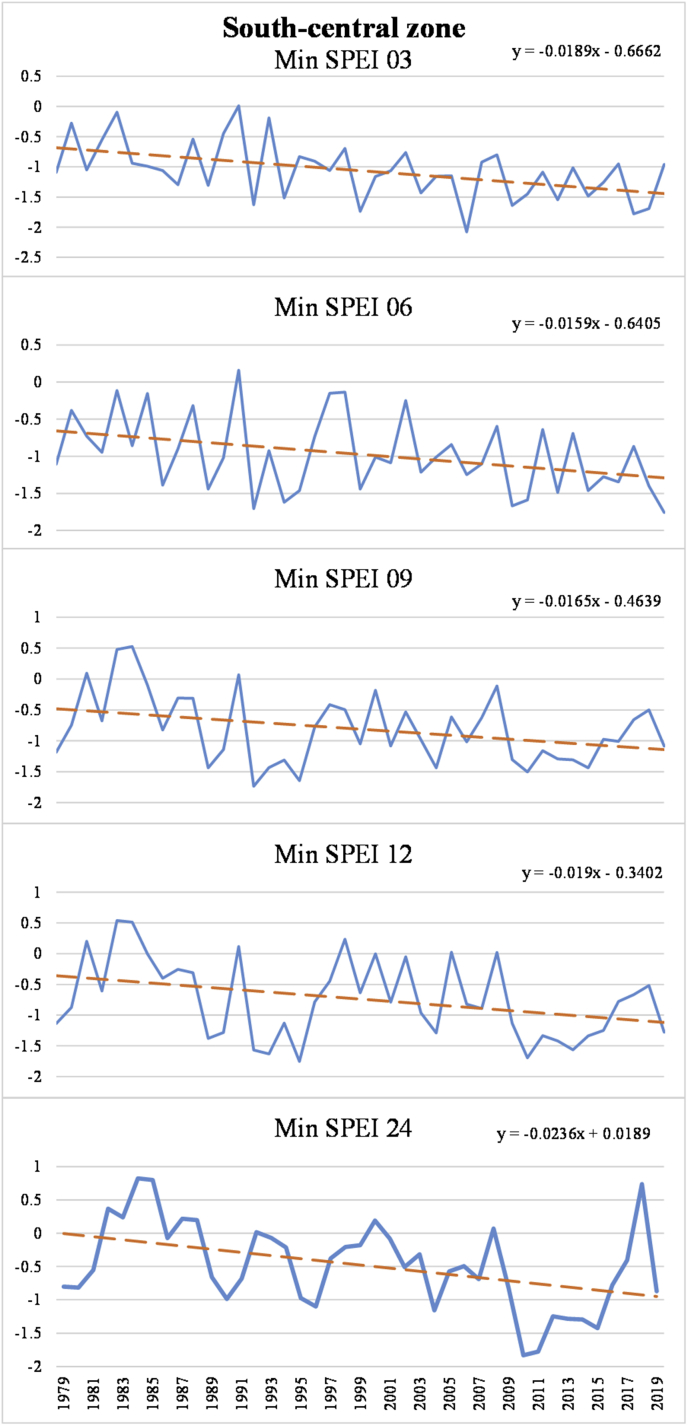

Average minimum SPEI of the Western zone and South-eastern zone in the time period of 1979–2019.

Figure 5.

Average minimum SPEI of South-central zone in the time period of 1979–2019.

Table 3.

Z values of Mann-Kendall test in 26 stations of SPEI 03, SPEI 06, SPEI 09, SPEI 12, and SPEI 24 for the time period of 1979–2019. Bold values represent the significant trend.

| Climatic zone | Station | SPEI 03 | SPEI 06 | SPEI 09 | SPEI 12 | SPEI 24 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Eastern Zone | Barisal | -2.84 | -3.49 | -3.31 | -2.75 | -3.79 |

| Chattogram | -1.22 | -0.80 | -1.13 | -1.47 | 0.21 | |

| Cox's Bazar | -1.02 | -0.12 | 0.60 | 0.48 | 0.30 | |

| Hatiya | -0.29 | 1.15 | 2.06 | 1.79 | 2.95 | |

| Khepupara | -0.62 | 0.38 | 1.01 | 0.83 | 0.99 | |

| M.Court | -0.10 | 1.25 | 2.13 | 2.06 | 1.85 | |

| Patuakhali | -2.02 | -0.99 | -1.06 | -0.80 | -1.20 | |

| Rangamati | -0.10 | 0.03 | -0.26 | -0.73 | 0.26 | |

| Sitakunda | -0.33 | 0.15 | 1.18 | 1.45 | 2.44 | |

| Teknaf | 1.18 | 2.39 | 2.98 | 2.26 | 2.44 | |

| North-eastern zone | Srimongal | -1.70 | 0.51 | 0.39 | 0.46 | 0.55 |

| Sylhet | -1.22 | -0.80 | -1.13 | -1.47 | 0.21 | |

| Northern part of northern region | Rangpur | -1.88 | -2.41 | -2.35 | -3.04 | -3.65 |

| North western region | Bogra | -2.28 | -2.30 | -2.82 | -2.80 | -4.50 |

| Dinajpur | -1.58 | -2.44 | -3.02 | -3.29 | -3.02 | |

| Ishurdi | -1.97 | -1.65 | -2.37 | -2.30 | -3.45 | |

| Western zone | Rajshahi | -2.57 | -2.89 | -3.04 | -2.73 | -4.35 |

| South western zone | Faridpur | -3.76 | -3.43 | -2.66 | -3.45 | -4.30 |

| Jashore | -1.67 | -2.41 | -2.03 | -2.03 | -1.52 | |

| Khulna | -2.12 | -3.04 | -2.01 | -1.52 | -1.65 | |

| Satkhira | -0.69 | 0.12 | -0.93 | -0.71 | -0.30 | |

| South Central Zone | Chandpur | -2.33 | -1.54 | -0.51 | -1.70 | -1.43 |

| Comilla | -1.18 | -0.60 | -0.26 | -0.73 | -0.93 | |

| Dhaka | -2.71 | -2.82 | -2.89 | -2.39 | -2.64 | |

| Madaripur | -2.01 | -0.26 | -0.64 | -1.29 | -2.12 | |

| Mymensingh | -0.95 | -0.01 | 0.01 | -0.55 | -1.92 |

Minimum SPEI values of SPEI 03, SPEI 06, SPEI 09, SPEI 12, and SPEI 24 in different zone reflects the highest dry period in a year in a 40-year time scale. Where every area has a decreasing rate in all SPEI values, the south-eastern location shows a different result which is an increasing rate in SPEI 09, SPEI 12, and SPEI 24 (0.0065, 0.007, 0.0128) with a minimum decreasing rate (−0.0001) in SPEI 06 (Figure 2) which is also reflected in MK test result. Three of the four significant trends in the south-eastern site, SPEI 09, SPEI 12, and SPEI 24, have an upward trend, while significant negative downward trends were observed for Barisal district in the south-eastern zone, corresponding to -2.84, -3.49, -3.31, -2.75, and -3.79 for SPEI 03, SPEI 06, SPEI 09, SPEI 12, and SPEI 24 respectively (Table 3 & Figure 6). On the other hand, the north-eastern zone shows no discernible trend. However, the northern part of the north of region has the highest value in SPEI (Figure 3) in some periods with the highest decrease rate in SPEI 06, SPEI 09, SPEI 12 (−0.268, -0.0308, -0.0356) which is reflected in the MK test where the result shows the significant downward trend for those SPEI classes of -2.41, -2.35, -3.04 and -3.65 from SPEI 06 to SPEI 24 accordingly. Similarly, the north-western zone experienced lowered rate for SPEI 09 (−0.0264), SPEI 12 (−0.0283) and SPEI 24 (−0.0386) where every station's MK test outcome sustained notable highest downward trend for Bogra (−4.50), Dinajpur (−3.02), Ishurdi (−3.45) corresponds SPEI 24. Equivalent results are obtained in the western area, with SPEI 24 (−0.0482) leaving a massive decreasing rate and a downward trend of drought severity from shorter to extended period represents -2.57, -2.89, -3.04, -2.73 and -4.35 for SPEI 03, SPEI 06, SPEI 09, SPEI 12, and SPEI 24 (Table 3 & Figure 6) respectively. Except for Satkhira, practically every station in the south-western zone has a significant negative trend for interannual, shorter, and biannual periods, with Z statistics of -2.41(SPEI 06), -2.03(SPEI 09), -2.03(SPEI 12) for Jessore, -2.12(SPEI 03), -3.04(SPEI 06), -2.01(SPEI 09) (Table 3 & Figure 6), and consequently, we identified an annual decline in all SPEI values (Figure 5). In the south-central zone, however, remarkably different results are obtained; only Dhaka in this zone shows a marked negative tendency in all SPEI classes corresponding to -2.71, -2.82, -2.89, -2.39, and -2.64 from SPEI 03 to SPEI 24 (Table 3 & Figure 6) with a decreasing rate yearly in all SPEI especially in SPEI 24 (0.0236). Overall, nine of the stations do not show a significant trend, whether downward or upward. Four of the nine stations are in the southeastern zone, namely Chattogram, Cox's Bazar, Khepupara, and Rangamati (Table 3 & Figure 6).

Figure 6.

MK test interpolation of SPEI 03, SPEI 06, SPEI 09, SPEI 12 and SPEI 24 of seven climatic regions in Bangladesh.

As mentioned earlier, Spatial distribution shows the same pattern in a result that is a significant downward trend in the northern part of the northern region, north-western zone, western zone, south-western zone (Figure 6). These parts of Bangladesh show that the dry periods have a downward trend in all SPEI, where the south-eastern area shows an entirely different result (Table 3). The South-eastern zone does not offer much significant downward trend but shows a significant upward trend in SPEI 09, SPEI 12, and SPEI 24 in the different stations (Figure 6). The North-eastern zone also does not have any significant upward and downward trend (Figure 6).

4. Discussion

This study detects most dry periods in the northern part of the northern region, North-western zone, western zone, and south western zone, representing that the dry periods are decreasing significantly in those areas. The decreasing rainfall trend in most of the stations validates the dry periods of stated zones (Bari et al., 2016; Rahman and Shozib, 2021). Miah et al. (2017) also revealed the Northern and North-western zone as the hotspot of the drought-prone region. Most of the stations in those zones have significant downward trends and drought periods, which is very similar to the previous studies (Mohsenipour et al., 2018; Uddin et al., 2020). Nevertheless, the dry periods are not decreasing significantly; moreover, they are increasing in some parts of the south-eastern zone, which is reflected in the SPEI and MK test results. This increasing trend, is observed in SPEI 06, 09, 12, and 24 moreover in the SPEI 09, 12, 24 which represents the long term dry periods increasing significantly proved by MK test (Kamruzzaman et al., 2019).

From 2009 to 2013 extreme dry periods are observed in this study in all zones, similar to (Mohsenipour et al., 2018; Uddin et al., 2020). Although in the north-eastern region, the year 1995–1997 faced severe drought conditions identical to the north-western zone. Those years faced extreme droughts than the other year in Bangladesh. In the north-eastern spot, the values are increasing, which means these areas face more rain than other periods. However, Mohsenipour et al. (2018) demonstrate the extreme conditions of prior dry periods; Roy (2013) justifies the findings for the north-eastern zone's drought conditions which define exacerbated precipitation conditions.

On the other hand, the values at the beginning of the periods have a high value which elucidates that the dry periods of this country are increasing day by day (Mohsenipour et al., 2018). Sometimes like mentioned before, this can be so much severe. The northern part of the northern region, western region, and the south-western region has maximum dry periods in the periods causing heavy decreasing rate, which has a terrible negative impact on the hydro climatological change of the respected places. In other literature, similar findings of extreme dry periods were proved for the northern and western zones (Murad and Islam, 2011; Rahaman et al., 2016; Shahid, 2008). Existing climate change, monsoonal wind, and the Himalayas presence are causing drought in the mentioned zone (Rahman and Lateh, 2016; Shahid, 2010). Also, a barrier of Farakka Barrage is responsible for shortages of water supply in Padma river resulted in drought in the south-western zone (WBB, 1998). As a result, gigantic sediment has accumulated in riverbeds, causing hydraulic congestion and lowering water pressure during dry periods (Abdullah, 2014; Arnell and Gosling, 2016). This also causes water scarcity and has an adverse impact on Bangladesh's microclimate and drought severity (Alam et al., 2011). However, the south-eastern zone has an increasing rate in the long term SPEI, which proves that the wet periods of this area have been increasing steadily, which is the only one scenario of all zones—similar scenario sustained by Habiba et al., (2013b) and Umma and Rajib (2014).

As the increasing trend observed in the south-eastern zone, this zone has a higher SPEI rate from 1999 to 2001, much more significant than any other zone. Relative fluctuations of sea surface heat and rainfall for the extensive period may lead to drought possibilities in the south-eastern zone (Ramamasy S, 2007). This period has higher SPEI rates, representing higher SPEI rates, representing that this area has faced fewer dry periods in this period, which less significant MK results can determine. Basak et al. (2013) also analyzed the rare drought events for the respected zone. MK results also show that the significance of the southeastern zone is very low. The Northern part of the northern region, north-western region, Western zone, and Southwestern zone hold the most significant result in trend analysis, proved in the previous statements. Changing temperature and rainfall patterns influence the increasing dry periods in Bangladesh, especially in these zones (Mohsenipour et al., 2018). Dry periods are increasing, and therefore the trend of increasing dry periods is happening, which may be considered an immediate concerning issue for the climate change variabilities in Bangladesh. In contrast, rainfall will also increase shortly which may lower drought possibilities (Islam et al., 2018). In addition, the different studies also depicting an upward trend of temperature that can lead to the reduction of seasonal precipitation may result in severe dry periods in Bangladesh (Rahman & Lateh, 2016, 2017).

5. Conclusion

The study performed drought intensity trend in spatiotemporal observation, which utilized Mann-Kendal trend test, Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI), and Inverse Distance Weighting Interpolation. The results signify heterogeneous spatial distribution followed by a particular trend—additionally, it emphasizes identifying excessive, severe and moderate drought formation that varies through SPEI demonstration. Strict drought-prone districts found in two climatic zones includes Jashore (>-1.50) and Khulna (>-1.65), covering the south-western zone and Mymensingh (>-1.90) covering the south-central location. Therefore, moderate drought is found in the south-eastern zone and south-central zone, which includes Patuakhali (>-1.20) and Chandpur (>1.40), respectively. Temporal drought changes vary actively, including both favorable and unfavorable 40 annual tendencies, while distribution variation also varies with degree of zoning. However, a homogeneous trending structure throughout all areas suggests minor unusual dryness measurements in Bangladesh. The study is expected to improve agricultural planning and water management in Bangladesh.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Md. Naimur Rahman: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Md. Rakib Hasan Rony & Farhana Akter Jannat: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Bangladesh Agricultural Research Council (BARC), Bangladesh Meteorological Department (BMD), and Syed Anowerul Azim (Assistant professor of Geography and Environmental Science, Begum Rokeya University, Rangpur) for providing and managing of meteorological datasets of our study area.

References

- Abdullah H.M. Proceedings of the IARU Sustainability Science Congress. 2014. Water harvest for drought resilient agriculture : prospect and possibilities in Bangladesh.https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Hasan-M-Abdullah/publication/275946332_Water_Harvest_for_Drought_Resilient_Agriculture_Prospect_and_Possibilities_in_Bangladesh/links/5549d8a70cf205bce7ac41dc/Water-Harvest-for-Drought-Resilient-Agriculture-Prospect-an [Google Scholar]

- Adhikary S.K., Muttil N., Yilmaz A.G. Cokriging for enhanced spatial interpolation of rainfall in two Australian catchments. Hydrol. Process. 2017;31(12) [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed A. 2006. Bangladesh Climate Change Impacts and Vulner-Ability-A Synthesis. [Google Scholar]

- Alam A.T.M.J., Saadat A.H.M., Rahman M.S., Barkotulla M.A.B. Spatial analysis of rainfall distribution and its impact on agricultural drought at barind region, Bangladesh. Rajshahi Univ. J. Environ. Sci. 2011;1(December):40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Alamgir M., Mohsenipour M., Homsi R., Wang X., Shahid S., Shiru M.S., Alias N.E., Yuzir A. Parametric assessment of seasonal drought risk to crop production in Bangladesh. Sustainability. 2019;11(5) [Google Scholar]

- Alexander D. Changing perspectives on natural hazards in Bangladesh. Nat. Hazards Obs. 1995;10(1) [Google Scholar]

- Alexandersson H. A homogeneity test applied to precipitation data. J. Climatol. 1986;6(6):661–675. [Google Scholar]

- Amini M.A., Torkan G., Eslamian S., Zareian M.J., Adamowski J.F. Analysis of deterministic and geostatistical interpolation techniques for mapping meteorological variables at large watershed scales. Acta Geophys. 2019;67(1) [Google Scholar]

- Arnell N.W., Gosling S.N. The impacts of climate change on river flood risk at the global scale. Climatic Change. 2016;134(3):387–401. [Google Scholar]

- Bae S., Lee S.-H., Yoo S.-H., Kim T. Analysis of drought intensity and trends using the modified SPEI in South Korea from 1981 to 2010. Water. 2018;10(3) [Google Scholar]

- Banglapedia . 2014. Banglapedia. Climatic Zone.https://mail.google.com/mail/u/1/#inbox/FMfcgzGlkPRbcFHtrwtrPVwJNNJQjDPB [Google Scholar]

- Banglapedia . 2014. Climate. Banglapedia.https://en.banglapedia.org/index.php/Climate [Google Scholar]

- Banglapedia . 2014. Drought. Banglapedia.https://en.banglapedia.org/index.php/Drought [Google Scholar]

- Bari S.H., Rahman M.T.U., Hoque M.A., Hussain M.M. Analysis of seasonal and annual rainfall trends in the northern region of Bangladesh. Atmos. Res. 2016;176–177:148–158. [Google Scholar]

- Basak J.K., Titumir R.A.M., Dey N.C. Climate change in Bangladesh: a historical analysis of temperature and rainfall data. J. Environ. 2013;2(2):41–46. www.scientific-journals.co.uk [Google Scholar]

- BMD . 2013. Bangladesh Meteorological Department. [Google Scholar]

- Buishand T.A. Some methods for testing the homogeneity of rainfall records. J. Hydrol. 1982;58(1):11–27. [Google Scholar]

- Burke E.J., Brown S.J., Christidis N. Modelling the recent evolution of global drought and projections for the twenty-first century with the Hadley Centre climate model. J. Hydrometeorol. 2006;7(5):1113–1125. [Google Scholar]

- Chen T., Ren L., Yuan F., Yang X., Jiang S., Tang T., Liu Y., Zhao C., Zhang L. Comparison of spatial interpolation schemes for rainfall data and application in hydrological modeling. Water (Switzerland) 2017;9(5) [Google Scholar]

- CWC . Ministry of Water Resources; India: 1996. Guidelines for Environmental Monitoring of Water Resource Projects. Central Water Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Danandeh Mehr A., Nourani V. A Pareto-optimal moving average-multigene genetic programming model for rainfall-runoff modelling. Environ. Model. Software. 2017;92:239–251. [Google Scholar]

- Danandeh Mehr A., Kahya E., Olyaie E. Streamflow prediction using linear genetic programming in comparison with a neuro-wavelet technique. J. Hydrol. 2013;505:240–249. [Google Scholar]

- Danandeh Mehr A., Sorman A.U., Kahya E., Hesami Afshar M. Climate change impacts on meteorological drought using SPI and SPEI: case study of Ankara, Turkey. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2020;65(2):254–268. [Google Scholar]

- Danandeh Mehr A., Hrnjica B., Bonacci O., Torabi Haghighi A. Innovative and successive average trend analysis of temperature and precipitation in Osijek, Croatia. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2021;145(3):875–890. [Google Scholar]

- Das S. Extreme rainfall estimation at ungauged sites: comparison between region-of-influence approach of regional analysis and spatial interpolation technique. Int. J. Climatol. 2019;39(1) [Google Scholar]

- Dash B.K., Rafiuddin M., Khanam F., Islam M.N. Characteristics of meteorological drought in Bangladesh. Nat. Hazards. 2012;64(2):1461–1474. [Google Scholar]

- Habiba U., Shaw R., Takeuchi Y. Farmer’s perception and adaptation practices to cope with drought: perspectives from Northwestern Bangladesh. Int. J. Disast. Risk Reduct. 2012;1:72–84. [Google Scholar]

- Habiba U., Shaw R., Hassan A.W.R. 2013. Drought Risk and Reduction Approaches in Bangladesh. [Google Scholar]

- Habiba U., Shaw R., Hassan A.W.R. In: Drought Risk and Reduction Approaches in Bangladesh BT - Disaster Risk Reduction Approaches in Bangladesh. Shaw R., Mallick F., Islam A., editors. Springer Japan; 2013. pp. 131–164. [Google Scholar]

- Hoque M.A.-A., Pradhan B., Ahmed N. Assessing drought vulnerability using geospatial techniques in northwestern part of Bangladesh. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;705:135957. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M.S., Qian L., Arshad M., Shahid S., Fahad S., Akhter J. Climate change and crop farming in Bangladesh: an analysis of economic impacts. Int. J. Clim. Change Strat. Manag. 2019;11(3):424–440. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC, I. P. O. C. C Climate change 2007 - the physical science basis: working group I contribution to the fourth assessment report of the IPCC. Science. 2007 October 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Islam A.R.M.T., Shen S.H., Yang S. Bin. Predicting design water requirement of winter paddy under climate change condition using frequency analysis in Bangladesh. Agric. Water Manag. 2018;195:58–70. [Google Scholar]

- Jerin J.N., Islam H.M.T., Islam A.R.M.T., Shahid S., Hu Z., Badhan M.A., Chu R., Elbeltagi A. Spatiotemporal trends in reference evapotranspiration and its driving factors in Bangladesh. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2021;144(1):793–808. [Google Scholar]

- Kabanda T. Long-term rainfall trends over the Tanzania coast. Atmosphere. 2018;9(4) [Google Scholar]

- Kamruzzaman M., Hwang S., Cho J., Jang M.W., Jeong H. Evaluating the spatiotemporal characteristics of agricultural drought in Bangladesh using effective drought index. Water (Switzerland) 2019;11(12) [Google Scholar]

- Kendall M.G. fourth ed. Charles Griffin; San Francisco, CA: 1975. Rank Correlation Methods. [Google Scholar]

- Mann H. Mann Nonparametric test against trend. Econometrica. 1945;13 [Google Scholar]

- McKee T.B., Nolan J., Kleist J. Preprints, Eighth Conf. On Applied Climatology, Amer. Meteor, Soc., January. 1993. The relationship of drought frequency and duration to time scales. [Google Scholar]

- Meena H.M., Machiwal D., Santra P., Moharana P.C., Singh D.V. Trends and homogeneity of monthly, seasonal, and annual rainfall over arid region of Rajasthan, India. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2019;136(3–4) [Google Scholar]

- Mehr A.D., Vaheddoost B. Identification of the trends associated with the SPI and SPEI indices across Ankara , Turkey. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- Mengyao Guo, D. S. S. C. L. Z. X. L. The use of SPEI and TVDI to assess temporal-SpatialVariations in drought conditions in the middle and LowerReaches of the Yangtze river basin, China. Adv. Meteorol. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- Miah M.G., Abdullah H.M., Jeong C. Exploring standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index for drought assessment in Bangladesh. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2017;189(11):547. doi: 10.1007/s10661-017-6235-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milan G., Slavisa T. Analysis of changes in meteorological variables using Mann-Kendall and Sen’s slopeestimator statistical tests in Serbia. Global Planet. Change. 2013;100:172–182. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra A.K., Singh V.P. A review of drought concepts. J. Hydrol. 2010;391(1–2) [Google Scholar]

- Mohsenipour M., Shahid S., Chung E. sung, Wang X. jun. Changing pattern of droughts during cropping seasons of Bangladesh. Water Resour. Manag. 2018;32(5) [Google Scholar]

- Mondol M.A.H., Zhu X., Dunkerley D., Henley B.J. Observed meteorological drought trends in Bangladesh identified with the Effective Drought Index (EDI) Agric. Water Manag. 2021;255:107001. [Google Scholar]

- Mortuza M.R., Moges E., Demissie Y., Li H.-Y. Historical and future drought in Bangladesh using copula-based bivariate regional frequency analysis. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2019;135(3):855–871. [Google Scholar]

- Murad H., Islam A.K.M.S. 3rd International Conference on Water and Flood Management. 2011. Drought assessment using remote sensing and gis in North-west region of Bangladesh; pp. 861–877. [Google Scholar]

- Nagarajan R. 2010. Drought Assessment. Springer Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Nourani V., Nezamdoost N., Samadi M., Daneshvar Vousoughi F. Wavelet-based trend analysis of hydrological processes at different timescales. J. Water Clim. Change. 2015;6(3):414–435. [Google Scholar]

- Nourani V., Danandeh Mehr A., Azad N. Trend analysis of hydroclimatological variables in Urmia lake basin using hybrid wavelet Mann–Kendall and Şen tests. Environ. Earth Sci. 2018;77(5) [Google Scholar]

- Pal J.S., Small E.E., Elathir E.A.B. Simulation of regional-scale water and energy budgets: representation of subgrid cloud and precipitation processes within RegCM. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2000;105(D24):29579–29594. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer Wayne C. U.S. Weather Bureau, Res. Pap. No. 45. 1965. Meteorological drought. [Google Scholar]

- Potop V., Boroneanţ C., Možný M., Štěpánek P., Skalák P. Observed spatiotemporal characteristics of droughton various time scales over the Czech Republic. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2014;115:563–581. [Google Scholar]

- Rahaman K.M., Ahmed F.R.S., Nazrul Islam M. Modeling on climate induced drought of north-western region, Bangladesh. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2016;2(1):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M.S., Islam A.R.M.T. Are precipitation concentration and intensity changing in Bangladesh overtimes? Analysis of the possible causes of changes in precipitation systems. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;690 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.06.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M.R., Lateh H. Meteorological drought in Bangladesh: assessing, analysing and hazard mapping using SPI, GIS and monthly rainfall data. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016;75(12) [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M.R., Lateh H. Climate change in Bangladesh: a spatio-temporal analysis and simulation of recent temperature and rainfall data using GIS and time series analysis model. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2017;128(1–2):27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M.R., Saha S.K. Flood hazard zonation-a GIS aidedmulticriteria evaluation approach (MCE) with remotely senseddata. Int. J. Geoinform. 2007;3(3):25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M.N., Shozib S.H. Seasonal variability of waterlogging in Rangpur city corporation using GIS and remote sensing techniques. Geosfera Indon. 2021;6(2):143–156. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A.T.M.S., Jahan C.S., Mazumder Q.H., Kamruzzaman M., Hosono T. Drought analysis and its implication in sustainable water resource management in Barind area, Bangladesh. J. Geol. Soc. India. 2017;89(1):47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M.A., Yunsheng L., Sultana N. Analysis and prediction of rainfall trends over Bangladesh using Mann–Kendall, Spearman’s rho tests and ARIMA model. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 2017;129(4) [Google Scholar]

- Ramamasy S B.S. 2007. Climate Variability and Change: Adaptation to Drought in Bangladesh-A Resource Book and Training Guidetle. [Google Scholar]

- Roy M. Time series, factors and impacts analysis of rainfall in North-eastern part in Bangladesh. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2013;3(8):1–7. www.ijsrp.org [Google Scholar]

- Salam R., Islam A.R.M.T., Pham Q.B., Dehghani M., Al-Ansari N., Linh N.T.T. The optimal alternative for quantifying reference evapotranspiration in climatic sub-regions of Bangladesh. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):20171. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-77183-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahid S. Spatial and temporal characteristics of droughts in the western part of Bangladesh. Hydrol. Process. 2008;22(13):2235–2247. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid S. Rainfall variability and the trends of wet and dry periods in Bangladesh. Int. J. Climatol. 2010;30(15):2299–2313. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid S., Behrawan H. Drought risk assessment in the western part of Bangladesh. Nat. Hazards. 2008;46(3) [Google Scholar]

- Shahid S., Hazarika M.K. Groundwater drought in the northwestern districts of Bangladesh. Water Resour. Manag. 2010;24(10):1989–2006. [Google Scholar]

- Shakhawat Hossain M., Arshad M., Qian L., Kächele H., Khan I., Din Il Islam M., Golam Mahboob M. Climate change impacts on farmland value in Bangladesh. Ecol. Indicat. 2020;112:106181. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S., Singh P.K. Long term spatiotemporal variability in rainfall trends over the state of Jharkhand, India. Climate. 2017;5(1) [Google Scholar]

- Shepard D. 23rd ACM National Conference. 1968. A two-dimensional interpolation function for irregularly spaced data; pp. 517–523. [Google Scholar]

- Shepard Donald. Proceedings of the 1968 23rd ACM National Conference. 1968. A two-dimensional interpolation function for irregularly-spaced data; pp. 517–524. [Google Scholar]

- Tong S., Lai Q., Zhang J., Bao Y., Lus A., Ma Q., Li X., Zhang F. Spatiotemporal drought variability on the Mongolian Plateau from1980–2014 based on the SPEI-PM, intensity analysis and Hurst exponent. Sci. Total Environ. 2017;615:1557–1565. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towfiqul Islam A.R.M., Rahman M.S., Khatun R., Hu Z. Spatiotemporal trends in the frequency of daily rainfall in Bangladesh during 1975–2017. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2020;141(3):869–887. [Google Scholar]

- Uddin M.J., Hu J., Islam A.R.M.T., Eibek K.U., Nasrin Z.M. A comprehensive statistical assessment of drought indices to monitor drought status in Bangladesh. Arab. J. Geosci. 2020;13(9):323. [Google Scholar]

- Umma H., Rajib S. Vol. 14. Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2014. Farmers’ response to drought in northwestern Bangladesh; pp. 131–161. (Risks and Conflicts: Local Responses to Natural Disasters). [Google Scholar]

- Venkateswarlu J. Disaster management: a national perspective. Drought Netw. News. 1992;4(1):4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Vicente-Serrano S.M. Differences in spatial patterns of drought on different time scales: an analysis of the Iberian peninsula. Water Resour. Manag. 2006;20(1):37–60. [Google Scholar]

- Vicente-Serrano, Sergio M. National Center for Atmospheric Research; 2015. The Climate Data Guide: Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) [Google Scholar]

- Vicente-Serrano S.M., Beguería S., López-Moreno J.I. A multi-scalardrought index sensitive to global warming: the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index. J. Clim. 2010;23(7):1696–1718. [Google Scholar]

- von Neumann J. Distribution of the ratio of the mean square successive difference to the variance. Ann. Math. Stat. 1941;12(4):367–395. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2235951 [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Pan Y., Chen Y. Comparison of three drought indices and their evolutionary characteristics in the arid region of northwestern China. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 2017;18(3):132–139. [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Wang Z., Yang H., Zhao Y. Study of the temporal and spatial patterns of drought in the YellowRiver basin based on SPEI. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2018;61:1098–1111. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Xu Y., Tabari H., Wang J., Wang Q., Song S., Hu Z. Innovative trend analysis of annual and seasonal rainfall in the Yangtze River Delta, eastern China. Atmos. Res. 2020;231 [Google Scholar]

- WBB . 1998. Water Resource Management in Bangladesh: Steps towards a New National Water Plan. [Google Scholar]

- Zinat M.R.M., Salam R., Badhan M.A., Islam A.R.M.T. Appraising drought hazard during Boro rice growing period in western Bangladesh. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2020;64(10):1687–1697. doi: 10.1007/s00484-020-01949-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.