Abstract

Introduction

Gliofibroma is a rare tumor that develops in the brain and spinal cord. Due to the rarity of its nature, its pathophysiology and appropriate treatment remain elusive. We report a case of intramedullary spinal cord gliofibroma that was surgically treated multiple times. This report is of great significance because this is the first case of recurrence of this tumor.

Case presentation

A 32-year-old woman complained of gait disturbance and was referred to our institution. At the age of 13 years, she was diagnosed with intramedullary gliofibroma and underwent gross total resection (GTR) in another hospital. Based on imaging findings, tumor recurrence was suspected at the level of cervical spinal cord, and surgery was performed. However, the resection volume was limited to 50% because the boundary between the tumor and spinal cord tissue was unclear and intraoperative neuromonitoring alerted paralysis. At 1 year postoperatively, the second surgery was performed to try to resect the residual tumor, but subtotal resection was achieved at most. At 2 years after the final surgery, no tumor recurrence was observed, and neurologic function was maintained to gait with cane.

Discussion

Although complete resection is desirable for this rare tumor at the initial surgery, there is a possibility to recur even after GTR with long-term follow-up. During surgical treatment for tumor recurrence, fair adhesion to the spinal cord is expected, and reoperation and/or adjuvant therapy might be considered in the future if the tumor regrows and triggers neurological deterioration.

Subject terms: Cancer of unknown primary, Chemotherapy

Introduction

Gliofibroma is a rare tumor that develops at the central nervous system (CNS). It was first reported in 1978 as an intracranial tumor in a 3-year-old girl [1]. Although this tumor has both glial and mesenchymal properties, their detailed histogenesis remains unclear. With regard to clinical aspects, treatment for this rare tumor varied among previous studies, and the efficacy of surgical resection and subsequent adjuvant therapy remains elusive. To date, there has been no report on the treatment of recurrent gliofibroma in the spinal cord. We report a case of gliofibroma in a 32-year-old woman who underwent surgery three times due to recurrence and regrowth.

Case presentation

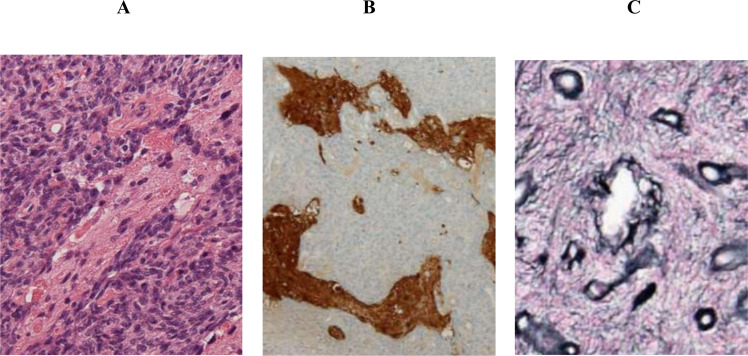

The patient was a 32-year-old woman who was diagnosed with recurrence of intramedullary spinal cord tumor and referred to our hospital for further treatment. At the age of 13 years, she underwent surgical resection of intramedullary tumor at the cervical spinal level in another institution. Before this surgery, enhancement was observed on gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 1A). Histology showed biphasic tumor consisting of dense proliferation of fibroblast-like spindle cells and small islands of glial component (Fig. 2A). While glial cells were positive for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), mesenchymal cells were negative for GFAP (Fig. 2B). Silver staining demonstrated increased reticulin fibers in the mesenchymal component (Fig. 2C). These findings confirmed a pathological diagnosis of gliofibroma.

Fig. 1. Before and after first surgery, the change of enhancement on Gd sagittal (MRI).

A Before first surgery, enhancement was observed. B At 1 month postoperatively, no contrast enhancement was detected. C At 3 years postoperatively, contrast enhancement was observed again.

Fig. 2. Histological findings at first surgery.

A Hematoxylin-eosin staining showed biphasic tumor consisting of dense proliferation of fibroblast-like spindle cells and small islands of glial component. B Immunostaining of glial fibrillary acidic protein showed glial cells were positive for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). C Silver staining showed increased reticulin fibers in the mesenchymal component.

At 1 month postoperatively, no contrast enhancement was detected (Fig. 1B). At 3 years postoperatively, contrast enhancement was observed again (Fig. 1C), suspecting tumor recurrence. However, she stopped visiting the previous hospital on her own judgment at 8 years postoperatively.

She had left hand clumsiness and gait disturbance 19 years after the initial surgery. At the first visit in our hospital, manual muscle test (MMT) score decreased at the left limbs, and deep tendon reflex was enhanced at both upper limbs and left lower limb. The Hoffman and Tromner reflexes were positive at the right hand, and the patient had numbness at the lower leg. ASIA(American spinal injury association) Impairment Scale(AIS) was D. MRI at the first visit of our hospital showed an intramedullary lesion at C6–C7 levels, low signal intensity on T1-weighted image, low to high signal intensity on T2-weighted image, and heterogeneous enhancement on gadolinium imaging (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. MRI at the first visit of our hospital.

A T1 sagittal and axial B T2 sagittal and axial C Gd sagittal and axial.

Since recurrent gliofibroma was suspected from the past medical history, surgical treatment was performed to attempt gross total resection (GTR). In the surgical findings, the boundary with the spinal cord tissue was unclear, and it was difficult to conduct total resection. Preoperative motor evoked potential (MEP) of the lower extremities showed positive wave only at the right abductor hallucis muscle and left quadriceps muscle. These waves disappeared during the surgical process of tumor resection, and the procedure resulted in 50% partial resection. Immediately after the surgery, both lower limbs presented complete motor paralysis but gradually improved to MMT 3 at 1 week postoperatively. AIS was D.

Histologically, the resected tumor showed biphasic tumor consisting of mesenchymal and glial component, which is consistent with recurrence of gliofibroma (Fig. 4A). Immunostaining and silver staining showed similar findings to the primary tumor. (Fig. 4B, C). The pathological diagnosis of second surgery was gliofibroma.

Fig. 4. Histological findings at second surgery.

A Hematoxylin-eosin staining showed biphasic tumor consisting of mesenchymal and glial component. B, C Immunostaining and silver staining showed similar findings to the primary tumor.

Unfortunately, residual tumor existed in contrast-enhanced MRI at 7 months postoperatively, and walking disability progressed over time. At 1 year postoperatively, we tried to achieve total resection once again due to the possibility that the residual tumor will increase in the future, as encountered in the initial situation. However, all waves of MEPs, except for the left quadriceps muscle, were not detected before surgery initiation. The residual tumor on the right side of the spinal cord was nearly resected, but the tumor on the left side was still large and had strong adhesion to the thinned spinal cord. The tumor was resected as much as possible but reached only subtotal resection (~80% resection) because the detected MEP wave of the left quadriceps muscle disappeared.

Immediately after surgery, only muscle contraction was observed at both lower extremities, and muscle weakness gradually improved. Nine months after the third surgery, she reacquired gait ability. AIS was D. Two years after the final surgery, no proliferation of the tumor was observed on MRI (Fig. 5), and neurologic function was maintained to gait with cane.

Fig. 5. Gd sagittal and axial(MRI) at 2 years after the final surgery.

No proliferation of the tumor was observed.

Statement of ethics

This study received ethical approval from the institutional review board (20110142). We certify that all applicable institutional regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research.

Discussion

Gliofibroma is a rare CNS tumor that is not listed in the current World Health Organization classification [2]. Its nature, pathophysiology, and appropriate treatment remain elusive due to insufficient evidence. The primary tumor develops mainly in childhood, and a female predominance of 2:1 has been reported [3]. The histological findings show biphasic features of both glial and mesenchymal characteristics, of which the latter is consistently benign [4]. The origin of the tumor-initiating cells is considered endothelial, histiocytic, fibroblastic, or multipotent glial/mesenchymal progenitors [5, 6]. Most of this tumor has benign properties without necrosis or microvascular proliferation and presents no metastasis after surgical resection [4]. MRI characteristics vary among the previous studies, which showed hypointense to hyperintense on both T1- and T2-weighted images. Differential diagnoses are gliomas, including astrocytomas and ependymomas. Surgical resection was usually performed as an initial treatment for this neoplasm, but the role of adjuvant therapy, such as radiation and chemotherapy, remains controversial.

In contrast to the frequency of development in the brain, development in the spinal cord is extremely rare, and there have been only ten cases, including the present case (Table 1). Although most cases showed therapeutic outcomes for primary tumor, this study is the first to present recurrent gliofibroma. Considering our case, even if GTR was performed at the initial surgery, this rare tumor has the potential to show recurrence with long-term follow-up. For recurrent gliofibroma, the GTR could not be achieved due to the adhesive property of this tumor to the spinal cord. Although 2 years have already passed since the last surgery was performed, careful observation for the remnant intramedullary tumor is required in the future.

Table 1.

Gliofibroma at the intramedullary spinal cord.

| Year | Author | Age | Therapy | Follow-up (year) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | Budka [11] | 45 | GTR | 1 | Alive |

| 1984 | Iglesias [12] | 0 | GTR | 4 | Alive |

| 1991 | Vazquez [13] | 9 | STR | 1.5 | Died |

| 1991 | Vazquez [13] | 5.5 | GTR | 2.5 | Alive |

| 1995 | Windisch [14] | 0.5 | GTR | 0.5 | Alive |

| 1998 | Sharma [15] | 24 | STR | 2 | Alive |

| 2002 | Matsumura [16] | 12 | GTR | 3 | Alive |

| 2002 | Itoh [7] | 11 | STR+ radiation | 2 | Alive |

| 2012 | Jones [17] | 5 | GTR | 4 | Alive |

| 2018 | Present case | 13 (First) | GTR | 8 | Alive |

| 32 (Recurred) | STR | 1 | Alive |

GTR gross total resection, STR subtotal resection.

Itoh et al. reported intramedullary gliofibroma, which was partially resected at the initial surgery [7]. In that case, radiation therapy (1.8 Gy/day; total, 39.6 Gy) was performed at 3 months postoperatively. One year after radiation therapy, tumor growth had ceased, and no neurological deterioration was observed. This was the only case of subtotal resection following radiation therapy for spinal cord gliofibroma, and this therapeutic strategy could be effective against tumor regrowth for a short period. With reference to that reported case, therapeutic radiation might be useful in preventing remnant tumor from regrowth in our case. However, evidence level was quite low for the efficacy of radiation therapy, and there remain concerns about radiation-induced injury or tumor in the future [8, 9]. Therefore, performance of radiation should be carefully decided in consideration of the risks and benefits of this adjuvant therapy.

From previous literatures, gliofibroma is likely to develop more frequently in the brain (Table 2). To the best of our knowledge, 33 cases in brain tumor have been reported. The total survival rate was 83.7% during the follow-up period, and 60.5% of patients underwent GTR. In patients with partial resection, adjuvant therapy, including radiation and/or chemotherapy, was performed in several cases, but the prognostic results varied. Among these studies, Suarez et al. presented a case of a patient who underwent partial resection of gliofibroma and subsequent chemotherapy (carboplatin and vincristine), which were effective without any regrowth for 3 years. In this case, the tumor size reduced to 1.5 × 1.2 cm by surgical resection, and these diameters were larger than those in our case, which showed 0.7 × 0.8 cm after the last surgery [10]. Although localization of the tumor was different between their case and ours, this chemotherapy might be one of the therapeutic options for inhibition of tumor regrowth.

Table 2.

Gliofibroma at the intracranial brain.

| Year | Author | Age | Therapy | Follow-up (year) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1978 | Freide [1] | 3.7 | Ax+RT+CT | 0.3 | Died |

| 1984 | Reinhardt [18] | 19 | GTR | 0.5 | Alive |

| 1986 | Jones [17] | 1.6 | Unknown | Unknown | Died |

| 1988 | Jones [17] | 3 | Unknown | Unknown | Died |

| 1990 | Bonin [13, 19] | 32 | Bx | 2 | Alive |

| 1991 | Snipes [5] | 0.17 | STR | 0.9 | Died |

| 1991 | Vazquez [13] | 0.9 | GTR | 2 | Alive |

| 1992 | Schober [6] | 18 | GTR | Unknown | Unknown |

| 1992 | Iglesias [12] | 1.2 | GTR | 1.5 | Alive |

| 1993 | Rushing [20] | 0.5 | GTR | 2 | Alive |

| 1993 | Cerda- Nicolas [21] | 9 | GTR | 0.5 | Alive |

| 1993 | Cerda-Nicolas [21] | 4 | Bx | Unknown | Unknown |

| 1995 | Caldemeyer [22] | 8 | Bx+CT | Unknown | Alive |

| 1995 | Caldemeyer [22] | 0.5 | GTR | Unknown | Alive |

| 1996 | Prayson [23] | 0.3 | STR | 3 | Alive |

| 1998 | Molenkamp [24] | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| 1998 | Sharma [15] | 10 | GTR | 0.3 | Alive |

| 1998 | Sharma [15] | 54 | GTR+RT | 0.5 | Died |

| 2003 | Kim Y [25] | 25 | GTR | 0.2 | Alive |

| 2003 | Kim NR [26] | 8 | GTR | 0.4 | Alive |

| 2004 | Suarez [10] | 0.3 | Bx+ CT | 3 | Alive |

| 2004 | Erguvan-Onal [27] | 16 | GTR | 1.2 | Alive |

| 2006 | Deb [28] | 15 | GTR | Unknown | Unknown |

| 2006 | Nomura [29] | 24 | GTR | 2.4 | Alive |

| 2007 | Goyal [30] | 8 | GTR+RT+CT | 1 | Alive |

| 2007 | Goyal [30] | 15 | GTR+RT+CT | 2 | Alive |

| 2007 | Goyal [30] | 40 | GTR+RT | 3 | Alive |

| 2009 | Sarkar [31] | 0.25 | Bx | 10 | Alive |

| 2011 | Altamirano [32] | 7 | STR+RT+CT | 0.3 | Died |

| 2013 | Jones [17] | 0.4 | Unknown | 3 | Alive |

| 2013 | Gargano [4] | 10.7 | GTR+RT+CT | 2 | Alive |

| 2015 | Kang [3] | 61 | STR | 4 | Alive |

| 2016 | Ahmad [33] | 23 | GTR+RT | 3 | Alive |

GTR gross total resection; STR subtotal resection; Ax autopsy; Bx biopsy; RT radiation therapy; CT chemotherapy.

Conclusion

We reported a case of gliofibroma that recurred in the intramedullary spinal cord. Although it is an extremely rare tumor and its treatment standard has not been established, GTR is desirable at the initial surgery. However, there is a risk of recurrence even after GTR with long-term follow-up. At the surgical treatment for tumor recurrence, fair adhesion to the spinal cord is expected, and reoperation and/or adjuvant therapy might be considered in the future if the tumor regrows and triggers neurological deterioration.

Data archiving

The data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Supplementary information

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41394-021-00461-y.

References

- 1.Friede RL. Gliofibroma; a peculiar neoplasia of collagen forming glia-like cells. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1978;37:300–13. doi: 10.1097/00005072-197805000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:803–20. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kang H, Kim JW, Se Y-B, Park S-H. Adult intracranial Gliofibroma: a case report and review of the literature. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2016;59:302–5. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2016.59.3.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gargano P, Zuccaro G, Lubieniecki F. Intracranial gliofibroma: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep. Pathol. 2014;2014:165025. doi: 10.1155/2014/165025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snipes GJ, Steinberg GK, Lane B, Horoupian DS. Gliofibroma. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:642–6. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.75.4.0642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schober R, Bayindir C, Canbolat A, Urich H, Wechsler W. Gliofibroma: immunohistochemical analysis. Acta Neuropathol. 1992;83:207–10. doi: 10.1007/BF00308481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Itoh Y, Takahashi M, SAsajima T, Mizoi K, Hatazawa J. Combined pilocytic astrocytoma and gliofibroma of the spinal cord: a report of a case. JST. 2002;16:171–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kikkawa Y, Suzuki S, Nakamizo A, Tsuchimori R, Murakami N, Yoshitake T, et al. Radiation-induced spinal cord glioblastoma with cerebrospinal fluid dissemination subsequent to treatment of lymphoblastic lymphoma. Surg Neurol Int. 2013;4:27. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.107905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Juthani RG, Bilsky MH, Vogelbaum MA. Current management and treatment modalities for intramedullary spinal cord tumors. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2015;16:39. doi: 10.1007/s11864-015-0358-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suarez CR, Raj AB, Bertolone SJ, Coventry S. Carboplatinum and vincristine chemotherapy for central nervous system gliofibroma: case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2004;26:756–60. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200411000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Budka H. Benign mixed glial-mesenchymal tumour (“glio-fibroma”) of the spinal cord. Acta Neurochir. 1980;55:141–5. doi: 10.1007/BF01808928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iglesias JR, Richardson EP, Jr, Collia F, Santos A, Garcia MC, Redondo C. Prenatal intramedullary gliofibroma. A light and electron microscope study. Acta Neuropathol. 1984;62:230–4. doi: 10.1007/BF00691857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vazquez M, Miller DC, Epstein F, Allen JC, Budzilovich GN. Glioneurofibroma: renaming the pediatric “gliofibroma”: a neoplasm composed of Schwann cells and astrocytes. Mod Pathol. 1991;4:519–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Windisch TR, Naul LG, Bauserman SC. Intramedullary gliofibroma: MR, ultrasound, and pathologic correlation. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1995;19:646–8. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199507000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma MC, Gaikwad S, Mehta VS, Dhar J, Sarkar C. Gliofibroma: mixed glial and mesenchymal tumour. Report of three cases. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1998;100:153–9. doi: 10.1016/S0303-8467(98)00028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsumura A, Takano S, Nagata M, Anno I, Nose T. Cervical intramedullary gliofibroma in a child: a case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2002;36:105–10. doi: 10.1159/000048362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones MC, Díaz V, D’Agustini M, Altamirano E, Baglieri N. Ricardo Drut Gliofibroma: report of four cases and review of the literature. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2016;35:50–61. doi: 10.3109/15513815.2015.1122124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reinhardt V, Nahser HC. Gliofibroma originating from temporoparietal hamartoma-like lesions. Clin Neuropathol. 1984;3:131–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonnin JM. Cystic gliofibroma of the fourthventricle. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1990;49:261A. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199005000-00007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rushing EJ, Rorke LB, Sutton L. Problems in the nosology of desmoplastic tumors of childhood. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1993;19:57–62. doi: 10.1159/000120701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cerda-Nicolas M, Kepes JJ. Gliofibromas (including malignant forms), and gliosarcomas: a comparative study and review of the literature. Acta Neuropathol. 1993;85:349–61. doi: 10.1007/BF00334444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caldemeyer KS, Zimmerman RA, Azzarelli B, Smith RR, Moran CC. Gliofibroma: CT and MRI. Neuroradiology. 1995;37:481–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00600101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prayson RA. Disseminated spinal cord astrocytoma with features of gliofibroma: a review of the literature. Clin Neuropathol. 2013;32:298–302. doi: 10.5414/NP300592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mölenkamp G, Riemann B, Kuwert T, Sträter R, Kurlemann G, Schober O. Monitoring tumor activity in low grade glioma of childhood. Klin Padiatr. 1998;210:239–42. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1043885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim Y, Suh YL, Sung C, Hong SC. Gliofibroma: a case report and review of the literature. J Korean Med Sci. 2003;18:625–9. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2003.18.4.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim NR, Suh YL, Shin HJ, Park IS. Gliofibroma with extensive calcified deposits. Clin Neuropathol. 2003;22:14–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erguvan-Onal R, Ateş O, Onal C, Aydin NE, Koçak A. Gliofibroma: an incompletely characterized tumor. Tumori. 2004;90:157–60. doi: 10.1177/030089160409000133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deb P, Sarkar C, Garg A, Singh VP, Kale SS, Sharma MC, et al. Intracranial gliofibroma mimicking a meningioma: a case report and review of literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2006;108:178–86. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2004.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nomura M, Hasegawa M, Kita D, Yamashita J, Minato H, Nakazato Y, et al. Cerebellar gliofibroma with numerous psammoma bodies. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2006;108:421–5. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goyal S, Puri T, Gunabushanam G, Sharma MC, Sarkar C, Julka PK, et al. Gliofibroma: a report of three cases and review of literature. Acta Oncol. 2007;46:1202–4. doi: 10.1080/02841860701316081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sarkar R, Yong WH, Lazareff JA. A case report of intraventricular gliofibroma. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2009;45:210–3. doi: 10.1159/000224617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Altamirano E. Gliofibroma, “Comunicación de un caso pediátrico y revisión de la bibliografía”. Patologia Rev Latinoam. 2011;49:221–5. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmad MU, Barborie A, Pizer B, Husband D, Mallucci C, Jenkinson MD, et al. Midbrain gliofibroma presenting in adulthood following “Cure” of a childhood intraventricular pilocytic astrocytoma. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2017;52:151–4. doi: 10.1159/000455920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.