Abstract

Introduction

Amyloid-beta (Aβ) protein is a major component of the extracellular plaque found in the brains of individuals with Alzheimer's disease (AD). In this study, we investigated the effect of trans-resveratrol as an antagonist treatment for moderate to mild AD, as well as its safety and tolerability.

Methods

This was a case–control study that enrolled 30 selected patients who had been clinically diagnosed with moderate to mild AD. These patients were randomly divided into two groups, namely, a placebo group (n = 15) and a trans-resveratrol group (n = 15) who received 500 mg trans-resveratrol orally once daily for 52 weeks. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examinations were performed on and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples were obtained from all participants before (baseline) and after the study (52 weeks). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays were used to determine the levels of plasma Aβ40 and Aβ42 and CSF Aβ40 and Aβ42.

Results

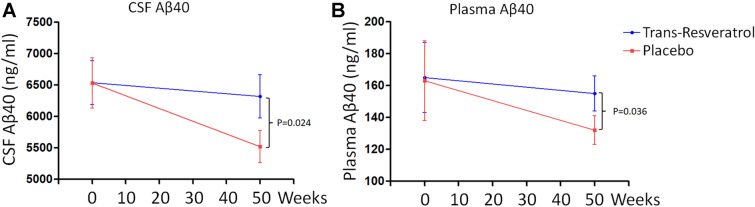

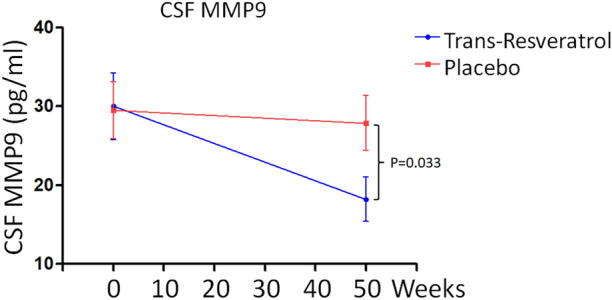

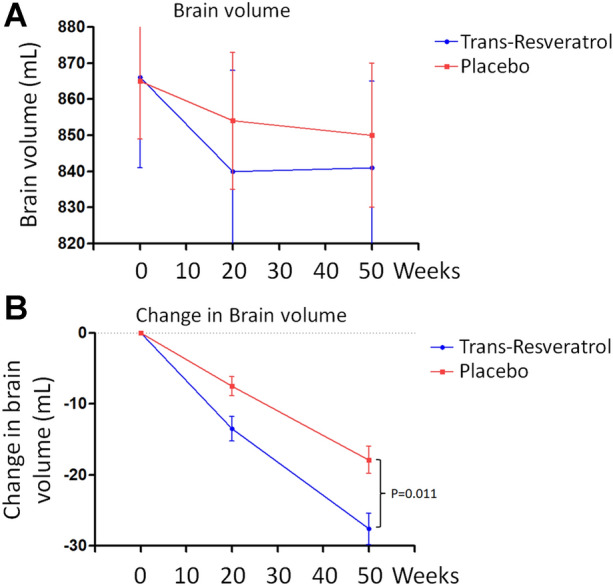

The results showed that the changes over the study period in the levels of Aβ40 in the blood and CSF of the patients treated with trans-resveratrol were not statistically significant (P > 0.05). In contrast, patients who received placebo showed a significant decrease in Aβ40 levels compared with that at the beginning of the study (CSF Aβ40: P = 0.024, plasma Aβ40: P = 0.036). Analysis of the images on the brain MRI scans revealed that the brain volume of the patients treated with trans-resveratrol was significantly reduced at 52 weeks (P = 0.011) compared with that of patients in the placebo treatment group, Further analysis indicated that the level of matrix metallopeptidase 9 in the CSF of the patients treated with trans-resveratrol at 52 weeks decreased by 46% compared with that of patients in the placebo group (P = 0.033).

Conclusion

These results indicate that trans-resveratrol has potential neuroprotective roles in the treatment of moderate to mild AD and that its mechanism may involve a reduction in the accumulation and toxicity of Aβ in the brain of patients, thereby reducing neuroinflammation.

Trial Registration

Chinese clinical trial registry: CTR20151780X.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40120-021-00271-2.

Keywords: Trans-resveratrol, Alzheimer disease, Amyloid Beta, MMP-9

Key Summary Points

| The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of trans-resveratrol as an antagonist treatment for moderate to mild Alzheimer's disease. |

| Patients who received placebo showed a significant decrease in amyloid-beta 40 protein levels at the end of the treatment period compared with the beginning of the study; in contrast, there was no change in patients who received trans-resveratrol dosage. |

| There was a notable reduction in the brain volume of patients treated with trans-resveratrol at the end of the study period compared with baseline. |

| Matrix metallopeptidase 9 level reduced by 46% at 52 weeks in the cerebrospinal fluid of the patients in the treatment group compared with the placebo group. |

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by progressive cognitive dysfunction [1]. Its pathological features are mainly senile plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and neuronal loss [1]. Plaques are primarily present in the cortex and hippocampus, and their main component is amyloid-beta (Aβ) deposition [2]. Aβ is a stimulant of chronic inflammation, activating glial cells through mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways, thereby causing the production of a large amount of inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin 1β and tumor necrosis factor α [2, 3]. These inflammatory cytokines further act on peripheral glial cells to amplify the inflammatory response, forming a positive feedback loop, leading to the increased production of oxygen-free radicals that in turn accelerates deterioration of AD and ultimately leads to neuronal loss and a decline in cognitive function [2, 3]. A characteristic sign of AD is the presence of tau proteins that are irregularly folded and aggregated into abnormal bundles of filaments [4, 5]. Abnormal tau phosphorylation has also been found to be more strongly associated with AD than with total tau (t-tau) [4, 5]. Consequently, AD is a disease with multiple etiologies and a complex pathogenesis. If only a certain etiology or pathological mechanism is targeted for treatment, positive outcomes are unlikely, accompanied by different degrees of adverse reactions. The drug development concept of “one target, one drug” has predominantly led to clinical application failure in the treatment of AD; therefore, multitarget treatment of AD has become a trend.

Resveratrol is a nonflavonoid polyphenol compound with a stilbenoid structure [6–8]. It is widely present in natural plants or fruits, such as grape, pine, Polygonum cuspidatum, cassia seed and peanut. Resveratrol is lipid soluble, easily crosses the blood–brain barrier, and is also a phytoestrogen that binds to estrogen receptors [6–8]. In vitro studies have confirmed that resveratrol enhances the function of cholinergic neurons, antagonizes Aβ toxicity, and reduces neuronal oxidative damage [9]. Red wine is rich in polyphenols, such as resveratrol and prostacyclin, which have antioxidant effects [10]. In this context, red wine has been demonstrated to protect cerebral blood vessels, inhibit the aging of and damage to brain nerve cells, and help prevent dementia. In December 2009, a study by scientists from the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Cincinnati showed that purple grape juice can alleviate and even cure memory loss [11]; the key component of grape juice and grape skin is the antioxidant resveratrol. In this study, 12 patients aged 75–80 years with symptoms of initial memory loss were equally divided into two groups. Six people drank the 100% grape juice made from whole grapes including seeds, and the other six were given a placebo. After a 3-month observation period, the memory of two groups was tested periodically, and the results indicated that the memory of the group that drank grape juice improved, with short-term, spatial and nonverbal memory exhibiting gradual improvement trends [11]. These findings suggest that resveratrol can be used in the treatment of AD.

Oxidative stress is a pathological state in which reactive oxygen species (ROS) are excessively generated and accumulate, which in turn causes oxidative damage to biological macromolecules, such as proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, resulting in various toxic effects on cells [12–14]. Oxidative stress plays an important role in the pathogenesis of AD. Studies have shown that the generation of ROS occurs earlier than the formation of Aβ deposition and neurofibrillary tangles in neurons and that the accumulation of ROS may be the primary cause of AD [15]. ROS is mainly produced in mitochondria. During oxidative stress, accumulated ROS induce mitochondrial damage, which aggravates the oxidative stress response and promotes the occurrence and development of AD [12–14]. Therefore, effectively controlling ROS production and protecting mitochondrial structure and function should be considered in the prevention and treatment of AD. Studies have found that resveratrol can initiate mitochondrial autophagy to degrade damaged mitochondria, reduce neuronal oxidative damage, and play a protective role in AD [16]. Due to its strong antioxidant effect, resveratrol can deacetylate forkhead transcription factor (FoxO3), p53, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1α (PGC1α) through SIRT1 to induce the expression of antioxidant enzymes, improve the antioxidant capacity of tissues and effectively remove ROS, such as hydroxyl, superoxide, and oxygen-containing free radicals [17]. Recent studies reported that the same dose of resveratrol can protect the learning ability and memory function of AD model mice and effectively scavenge malondialdehyde, a metabolite of lipid peroxidation in the body, enhance the activity of superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase, and improve the antioxidant capacity of the body [18–20]. To date, the antioxidant effect of trans-resveratrol in AD development has not been studied in detail, and the mechanism has not been clearly elucidated.

There are four main forms of resveratrol in nature, i.e., cis- and trans-resveratrol and cis- and trans-resveratrol glycosides, and the trans-isomer of resveratrol glycosides can be converted to the cis-isomer under ultraviolet light irradiation [6–8]. The physiological activity of the trans-isomer is greater than that of the cis-isomer, and the activity of monomers is greater than that of the glycosides [6–8]. In plants, resveratrol usually exists in the form of stable transglycosides. Several clinical studies of resveratrol are under process, including studies on age-related cognitive loss similar to AD [21–23]. Turnor er al. [23] reported a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter 52-week phase 2 trial of resveratrol in individuals with mild to moderate AD. They recruited 119 participants who were randomized to placebo or resveratrol (with dose escalation by 500-mg increments every 13 weeks, ending with 1000 mg twice daily). The results from this study indicated that cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) amyloid-beta 40 (Aβ40) and plasma Aβ40 levels declined more in the placebo group than the resveratrol-treated group and that brain volume loss was increased by resveratrol treatment compared to placebo [23]. Moussa et al. [21] studied changes in Aβ/tau, cytokines, and matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP-9) within a subset of AD subjects, demonstrating that treatment with resveratrol could attenuate progressive declines in CSF Aβ40 levels and activities of daily living (ADL) scores. In the study study reported here, we investigated the antagonistic effect of trans-resveratrol on moderate to mild AD.

Methods

Study Design

The was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital affiliated with the Zhejiang University School of Medicine (SRRSH2017-0075A). Each patient provided written informed consent prior to be included in the study. The study was performed in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The AD group included patients with AD who had been clinically diagnosed in the Department of Neurology of Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, Hangzhou, Zhejiang between 2017 and 2019. The inclusion criteria for the AD group were: (1) age of onset ≥ 65 years and no familial genetic history of dementia; (2) clinical examination and mini-mental state examination (MMSE) evaluation, with MMSE scores lower than the critical values (illiteracy ≤ 17 points; elementary school education ≤ 20 points; middle school education and higher ≤ 24 points); (3) absence of depression, with a Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) score < 7 points (17-item version); (4) Hachinski Ischemic Scale (HIS) score ≤ 4 points; and (5) diagnosed by at least one neurologist, in line with the “probable AD” diagnostic criteria of the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA). The exclusion criteria for the AD group were: (1) familial history of dementia; (2) not “likely to have AD”; (3) depressive symptoms (HDRS score > 17 points); (4) HIS score > 4 points; and (5) myocardial infarction, heart failure, type 2 diabetes, stroke, and autoimmune diseases. Thirty patients (16 men, 14 women) were enrolled in the study, and all clinical data on these patients were collected. The mean age (± standard deviation [SD]) was 72.35 ± 6.64 years, and the disease course was 1–3 years. Participants were assigned to the trans-resveratrol or placebo arm with an allocation ratio of 1:1 and assignment to groups was randomized. See Table 1 for the baseline characteristics of both groups of patients.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the trans-resveratrol and placebo groups

| Patient characteristics at baseline | trans-Resveratrol group (n = 15) | Placebo group (n = 15) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 7 (46.6) | 7 ± 46.6 | 1a |

| Age (years) | 71.5 ± 6.5 | 72.8 ± 5.3 | 0.351a |

| AD duration (years) | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 1.8 ± 0.9 | 0.426a |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.3 ± 2.8 | 25.5 ± 3.1 | 0.307b |

| MMSE score | 20.3 ± 3.2 | 20.4 ± 2.9 | 0.635b |

| CDR-SOB score | 5.2 ± 1.6 | 5.2 ± 1.5 | 0.812b |

| ADCS-ADL score | 61.3 ± 13.2 | 60.9 ± 12.4 | 0.525b |

| NPI score | 9.8 ± 6.5 | 9.5 ± 7.7 | 0.414b |

| ADAS-Cog score | 24.3 ± 9.5 | 25.1 ± 10.3 | 0.313b |

| Brain volume (mL) | 866.3 ± 91.2 | 864.1 ± 108.5 | 0.515b |

| Ventricular volume (mL) | 55.2 ± 6.3 | 56.1 ± 14.3 | 0.347b |

| CSF Aβ40 (ng/mL) | 6522 ± 1877 | 6537 ± 1688 | 0.667b |

| Plasma Aβ40 (ng/mL) | 163.7 ± 35.3 | 164.3 ± 40.5 | 0.733b |

Values in table are the mean ± standard deviation (SD) unless indicated otherwise

AD Alzheimer’s disease, ADAS-Cog Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive, ADCS-ADL Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Activities of Daily Living Scale, BMI body mass index, CDR-SOB Clinical Dementia Rating-sum of boxes, CSF cerebrospinal fluid,MMSE Mini-Mental State Examination, NPI Neuropsychiatric Inventory

aFisher exact test

bWilcoxon rank-sum test

In this study, high-purity trans-resveratrol and identical placebo were obtained from the Zhejiang New Secco Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd (Shangyu City, China). trans-Resveratrol was administered according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Specific dosage regimens were used. First, the participants were divided into two groups: the placebo group (n = 15) and the trans-resveratrol group (n = 15). Placebo (500 mg) and trans-resveratrol (500 mg) were administered to the patients orally every day. The experiment was conducted for 1 year. With the exception that the first dose was administered in the hospital, the remaining treatments were all self-administered at home once a day, at a recommended fixed time every day; all patients were provided with education on the diagnosis and on the follow-up. Detailed patient files were established; basic information, adverse events (AEs) review, symptoms and signs, medical history, physical and neurologic examination, Aβ test results and drug usage of each patient were documented; regular follow-up visits were scheduled. During the treatment period, if a patient had systemic or local adverse reactions, under the guidance of the clinicians, appropriate symptomatic drugs were prescribed or appropriate dose adjustment was made to relieve the adverse symptoms. All patients underwent brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) before and after the study. The procedure and quantification of the brain MRI results were performed as previously described [23]. The cognitive tests were performed for secondary outcomes, including scores on the MMSE and ADL.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Approximately 5 mL of fasting venous blood was collected from the participants in the morning, with EDTA used as anticoagulant. The collected blood was allowed to stand for 2 h and then centrifuged for 20 min (2000 rpm). The upper layer (plasma) was carefully collected and stored in a freezer at − 80 °C. The levels of Aβ40 and amyloid-beta 42 (Aβ42) in the CSF and plasma were detected using a double-antibody sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit purchased from Shanghai Lianshuo Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) Purified human Aβ40 antibody was used to coat microplates to prepare solid-phase antibodies. Aβ40 and Aβ42 antigens were sequentially added to the microplates coated with monoclonal antibody and then combined with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled goat anti-human antibody to form an antibody–antigen–enzyme-labeled antibody complex, which was washed thoroughly, followed by color development with TMB substrate. TMB is converted to blue following catalysis of the HRP enzyme and converted to yellow when exposed to; the color intensity is positively correlated with Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations in samples. Absorbance (OD value) was measured using a microplate reader at a wavelength of 450 nm. The concentrations of human Aβ40 and Aβ42 antigens in the samples were calculated using a standard curve. The R value of the correlation coefficient between the linear regression of the sample and the expected concentration was > 0.990, and the intrabatch and interbatch differences were < 9 and 11%, respectively. All samples had duplicate wells, and experiments were performed strictly in accordance with the manufacturor’s instructions. p-tau181P and t-tau concentrations were measured using a commercially available ELISA kit (Fujirebio, Ghent, Belgium). The CSF MMP-9 protein level was quantified using the Human MMP-9 Quantikine ELISA Kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed and graphs were plotted using the SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS Inc. IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) software packages, respectively. The general characteristics of the two groups were compared using the Fisher exact test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Comparison of the mean of multiple samples was performed using one-way analysis of variance. The pairwise comparison of the means of multiple samples was performed using the Newman–Keuls multiple comparison test in the analysis of variance. The relationship between the two variables was analyzed using linear correlations, and differences were considered to be statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Adverse Events

At each visit, all the participants received physical and neurological examinations and their vital signs were taken. Safety and tolerability were evaluated based on the severity and causality of the AEs. The most frequent AEs by system (see Table 2) and by number of patients were nervous system disorders, including headache (6 patients on trans-resveratrol and 6 on placebo); gastrointestinal disorders, such as diarrhea (6 patients on trans-resveratrol and 5 on placebo), nausea (3 patients on trans-resveratrol and 2 on placebo); injury, poisoning, or procedural complications, such as fall (4 patients on trans-resveratrol and 4 on placebo); weight decrease (6 patients on trans-resveratrol and 3 on placebo); musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders, such as back pain (3 patients on trans-resveratrol and 4 on placebo), arthralgia (2 patients on trans-resveratrol and 2 on placebo); skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders, such as rash (1 patient on trans-resveratrol and 2 on placebo); there was one patient with basal cell carcinoma in the placebo group.

Table 2.

Participants with adverse events by system

| System | trans-Resveratrol (n = 15), n (%) | Placebo (n = 15), n (%) | p value (Fisher exact test) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infections and infestations | 6 (40) | 6 (40) | 1 |

| Nervous system disorders | 6 (40) | 6 (40) | 1 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 6 (40) | 5 (33.3) | > 0.9 |

| Psychiatric disorders | 5 (33.3) | 5 (33.3) | 1 |

| Injury, poisoning, or procedural complications | 4 (26.6) | 4 (26.6) | 1 |

| Weight loss | 6 (40) | 3 (20) | 0.426 |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 3 (20) | 4 (26.6) | > 0.9 |

| General disorders and administrative site conditions | 2 (13.3) | 2 (13.3) | 1 |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | 3 (20) | 3 (20) | 1 |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 1 (6.7) | 2 (13.3) | > 0.9 |

| Renal and urinary disorders | 1 (6.7) | 1 (6.7) | 1 |

| Vascular disorders | 1 (6.7) | 1 (6.7) | 1 |

| Cardiac disorders | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Eye disorders | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0) | > 0.9 |

| Neoplasms benign, malignant, and unspecified | 0 | 1 (6.7) | > 0.9 |

Outcome

The cognitive tests, including the MMSE and Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study (ADCS)-ADL scale were performed to detect differences in clinical outcomes. Comparison of the baseline and end-of-study MMSE scores showed that the mean (± SD) MMSE score increased from 20.3 ± 3.2 at baseline to 21.44 ± 3.11 at week 52 in trans-resveratrol-treated patients and from 20.4 ± 2.9 to 20.56 ± 4.69 in placebo-treated patients during this same period (comparison at week 52 p = 0.76). The mean ADL score in the drug-treated group fell from 61.3 ± 13.2 at baseline to 56.1 ± 11.3 at week 52 and from 60.9 ± 12.4 to 50.2 ± 12.2 during this same period in the placebo group (comparison at week 52 p = 0.06), indicating trans-resveratrol attenuated the decline in the ADL score during the 12-month study.

Biomarkers

The mean (± SD) CSF Aβ40 concentration in trans-resveratrol-treated patients fell from 6522 ± 1877 ng/mL at baseline to 6423 ± 1344 ng/mL at week 52; in the placebo group, the CSF Aβ40 concentration fell from 6537 ± 1688 ng/mL at baseline to 5541 ± 982 ng/mL at week 52. The difference in CSF Aβ40 concentration at week 52 was significant (p = 0.024) (Fig. 1a). During the study, the mean plasma Aβ40 concentration in the trans-resveratrol treated group (Fig. 1b) fell from 163.7 ± 35.3 to 158.4 ± 38.2 ng/mL at week 52, and from 164.3 ± 40.5 to 137.5 ± 31.2 ng/mL in the placebo group (p = 0.036). In contrast, no treatment effects were observed on CSF Aβ42 or plasma Aβ42 (Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM] Table 1). There was no difference in the level of CSF tau and phospho-tau 181 (ESM Table 2). Further, we found that trans-resveratrol treatment had an effect on the decrease of CSF MMP-9 level at week 52 (19.2 ± 4.6 pg/mL) compared to the level at baseline (29.8 ± 5.6 pg/mL; p = 0.033; Fig. 2). There was no significant change in CSF MMP-9 protein level between the baseline and week 52 in the placebo group.

Fig. 1.

Biomarkers. Treatment with trans-resveratrol altered the levels of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) amyloid-beta 40 (Aβ40) (a) and plasma Aβ40 (b). Data are the mean ± standard error (SE)

Fig. 2.

Change in CSF matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP-9) levels from baseline to week 52. Data are the mean ± SE

Brain Volume

Volumetric MRIs revealed that brain volume declined more in the treatment group (p = 0.011) at week 52 (Fig. 3a, b) than in the placebo group. In the treatment group, the mean (± SD) brain volume decreased from 866.5 ± 33.4 at baseline to 841.3 ± 25.6 mL at week 52; in the placebo group, it decreased from 865.9 ± 14.3 to 854.1 ± 18.9 mL (Fig. 3a, b).

Fig. 3.

trans-Resveratrol increased brain volume loss (a,b). Data are the mean ± SE

Discussion

Alzheimer's disease is a diffuse degenerative disorder of the central nervous system characterized by progressive memory and intelligence loss that occurs in old age and preaging [1]. Resveratrol is a plant estrogen that binds to estrogen receptors. In vitro studies have confirmed that resveratrol can enhance the function of cholinergic neurons, antagonize Aβ toxicity, and reduce oxidative damage in neurons [9]. Studies have also shown that resveratrol may have a protective effect on the central nervous system [24, 25]. In one study, 119 patients with mild to moderate dementia were recruited for a randomized, two-phase, placebo-controlled, double-blind study using resveratrol as the test substance [6–8], and the treatment shown that resvertrol plays a protective effect on AD [23]. The main difference between trans-resveratrol and resveratrol is their structure [6–8]. trans-Resveratrol is one of the two geometric isomers of resveratrol. trans-Resveratrol has a planar main chain, while cis-resveratrol contains two main planes [6–8]. We investigated the neuroprotective role as well as the safety and tolerability of trans-resveratrol in individuals with moderate to mild AD. Our results show that trans-resveratrol stabilized the progressive decline in the levels of Aβ40 in the blood and CSF with advancing dementia compared to patients who received placebo (CSF: P = 0.024, plasma: P = 0.036, Fig. 1a, b). Brain MRI scans demonstrated that the brain volume of the patients treated with trans-resveratrol was significantly reduced (P = 0.011; Fig. 3) compared with that of patients in the placebo treatment group. Therefore, these data indicate that trans-resveratrol is neuroprotective in the treatment of moderate to mild AD. In addition, we performed cognitive tests, including MMSE and ADCS-ADL, and analyzed the differences in clinical outcomes. Although there was no difference in the MMSE at baseline and its status at the end of the study, the drug-treated group’s ADL score declined from 61.3 ± 13.2 at baseline to 56.1 ± 11.3 at week 52 and that of the placebo group fell from 60.9 ± 12.4 to 50.2 ± 12.2 during this same period (comparison at week 52, p = 0.06), indicating trans-resveratrol attenuated the decline in independent living performance.

We observed the phenomenon that trans-resveratrol treatment increased brain volume loss compared to the placebo-treated group. This is paradoxical compared to the current consensus that the main hallmark of moderate to severe AD is a decrease in the volume of the cerebral cortex and hippocampus [1]. The etiology of brain volume loss observed in our study was not associated with cognitive or functional decline; however, the detailed mechanism is unclear. One possible mechanism is that trans-resveratrol has potent anti-inflammatory effects in the AD brain. One study reported similar effects with, for example, anti-amyloid immunotherapies for AD [26], with those responding to antibody following Aβ immunization (AN1792) having greater brain volume loss after evaluation on MRI measures of cerebral volume in AD [26].

Our study showed that daily doses of 500 mg of trans-resveratrol during a 52-week period could be a suitable treatment for mild to moderate AD. This dose of trans-resveratrol was lower than those used in investigations by Turner et al. [23] and Moussa et al. [21]. These studies used a treatment regimen of progressively increasing daily doses from 500 to 2000 mg of resveratrol for 52 weeks. Turner et al. [23] reported increased brain volume loss and lower decline of Aβ40 in CSF and plasma in patients dosed for 52 weeks. They further showed that the MMP-9 level in the CSF of the patients in the treatment arm decreased by 50% [23]. Moussa et al. [21] reported attenuated cognitive decline, attenuated decline of Aβ40 level in CSF and plasma samples, and decreased level of MMP-9 in CSF. Similarly, our study was performed in patients with AD at early stages (mild to moderate disease). The placebo and trans-resveratrol group each consisted of 15 patients who were treated for 52 weeks. Our study differs from those of Turner et al. [23] and Moussa et al. [21] in that we administered oral 500 mg doses of the most active isomer trans-resveratrol. All participants were monitored for changes in brain volume, Aβ levels in plasma and CSF, and MMP-9 level in CSF. A reduction in brain volume was detected in the trans-resveratrol-treated patients. Also, the level of Aβ40 was maintained in plasma and CSF of trans-resveratrol-treated patients in contrast to a decrease found in placebo-treated patients (Fig. 1a, b). More importantly, the level of MMP-9 in the CSF of patients who received trans-resveratrol was reduced by 46% (Fig. 2). Under normal circumstances, low MMP-9 levels have antagonistic effects on AD development. MMP9 deficiency leads to the reduction of neuroinflammation in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis [27], while CSF MMP9 is elevated in patients with bacterial meningitis and blood–brain barrier (BBB) damage [28]. A high level of MMP-9 leads to penetration of the BBB, allowing proteins and molecules to enter the brain from the body. Thus, these results indicate that compared with patients treated with placebo, the administration of resveratrol to AD patients can restore the integrity of the BBB, reduce the ability of harmful immune molecules secreted by immune cells to infiltrate into brain tissue, and reduce and slow cognitive decline in patients with neuroinflammation [23]. trans-Resveratrol prevents AD progression, possibly by maintaining the integrity of the BBB via its reducing effect on MMP9, which induces adaptive immune responses that may promote brain resilience to amyloid deposition. trans-resveratrol may slow cognitive decline in AD via the adaptive immune response. Therefore, compared to the above-mentioned studies [21, 23], the results from our study demonstrate that trans-resveratrol at the daily doses of 500 mg for 52 weeks has neuroprotective properties in patients with mild to moderate AD associated with Aβ and neuroinflammation. Further, the use of a mixture of cis- and trans-isomers of resveratrols would induce lower effects than pure trans-resveratrol; however, this would involve a different treatment with a different drug composition and is thus beyond the scope of the present study. Resveratrol has low bioavailability and the micronization or the exact formulation can make a difference in the absorption; these factors should be considered in a different clinical study.

Resveratrol has a variety of biological activities and can effectively prevent and treat AD through its synergistic multitarget action [29]. Results from the present study demonstrate that Aβ40 levels in blood and CSF from patients treated with trans-resveratrol did not change significantly (P > 0.05). In contrast, in comparison to baseline levels, the Aβ40 levels in patients who received placebo had fallen significantly by the end of the study (CSF: P = 0.024; plasma: P = 0.036; Fig. 1a, b). Non-significant trends were found for CSF Aβ42 and plasma Aβ42 (ESM Table 1). These data indicate that the neuroprotective mechanism of trans-resveratrol may involve a reduction in the accumulation and toxicity of Aβ in the brain of patients, thereby reducing neuroinflammation. In a recent study, Porquet, D. et al. looked at the effect of trans-resveratrol on learning and memory in an Aβ25-35-induced AD mouse model [30]. These authors found that the administration of trans-resveratrol significantly shortened the latency of AD mice to find a platform and increased the residence time and number of crossings in the quadrant of the original platform; furthermore, trans-resveratrol increased the length and density of dendrites at the top of neurons in hippocampal CA1 area [30]. In terms of the molecular mechanism, many target substrate proteins interact with resveratrol. According to the Aβ cascade hypothesis, amyloid precursor protein is hydrolyzed by β- and γ-secretases to produce neurotoxic Aβ and its aggregates, which are the initiating factors of and key links to the pathogenesis of AD [2, 31]. Neurotoxic Aβ and its aggregates then initiate the pathological cascade reaction, leading to the loss of neurons and synapses and damaging the structure and function of brain tissue, eventually causing dementia. The key to preventing and treating AD is to reduce the excessive formation of Aβ, prevent Aβ deposition, remove deposited Aβ, and maintain the production and degradation of Aβ in a dynamic balance [3]. Resveratrol can not only effectively inhibit the formation of Aβ but also effectively prevent its aggregation and deposition [21, 32]. γ-Secretase is involved in the synthesis of Aβ, and its activity has an important relationship with the occurrence and development of AD. Resveratrol inhibits γ-secretase activity through the regulation of general control nonderepressible 2 (GCN2) by the autophagolysosome system, thereby effectively inhibiting the formation of Aβ. In addition, as a natural activator of sirtuin 1 (Sirt1), resveratrol activates the transcriptional expression of Sirt1-dependent ADAM10 (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein 10), increases the production and activity of α-secretase, and reduces the production of Aβ [9, 20, 33]. Studies have found that resveratrol can effectively prevent Aβ aggregation and deposition and that the aggregation of Aβ25-35 is inhibited by resveratrol in a dose-dependent manner [9, 20, 33]. Resveratrol also removes deposited Aβ. Resveratrol initiates the AMPK–Sirt1–autophagy pathway by activating AMPK to rapidly clear deposited Aβ. Resveratrol can also inhibit the toxic damage caused by Aβ25-35, Aβ40 and Aβ42 in a dose-dependent manner and exert a protective effect on neurons. The administration of resveratrol before and during Aβ25-35 injury can inhibit the toxic effects of Aβ25-35 and improve the survival rate of hippocampal neurons [30]. Even if resveratrol is administered after an injury, it can still effectively play a protective role and save dying neurons. Therefore, trans-resveratrol plays the neuroprotective role by inhibiting the toxic effects of Aβ deposition in the neurons.

In addition, increased CSF t-tau has been found in a variety of other neurological disorders, including frontotemporal dementia [4, 5, 34]. Further, CSF p-tau181 is a highly specific biomarker of AD pathology [4, 5, 34]. Our results show that there was no difference in the level of CSF tau and p-tau181 (ESM Table 2) at baseline and treatment at week 52. These results demonstrated that treatment of trans-resveratrol for AD had no effect on t-tau and p-tau181 levels, suggesting no treatment effect of trans-resveratrol on neuronal loss.

There are some limitations to this study. The sample size is small and, therefore, a multicenter placebo-controlled study is required to include more patients with AD (mild to moderate) for validation of the results. Second, MMP-9 is an Aβ-degrading enzyme and may function as a neuroprotective molecule, as has been previously reported [35]. Thus, it will be necessary to measure and compare CSF MMP-9 activity between placebo and trans-resveratrol-treated groups. Finally, there are also reports of AEs associated with resveratrol treatment for AD. For example, certain doses of resveratrol may increase Aβ production and cell death in a cellular AD model [29]. Therefore, several other markers of inflammation and brain cell death as well as neuroprotection require further investigation.

Conclusions

In summary, results from this pilot study demonstratedthe neuroprotective role of trans-resveratrol in patients with mild to moderate AD. Further evaluation of the safety and tolerability of trans-resveratrol demonstrated that this medication may be a promising treatment for AD.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the study.

Funding

This research was supported by Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No.LY19H090018, Project 81401038 supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China, and Zhejiang Province Medicine Health General Research Program (2020KY602). The journal’s Rapid Service Fee was provided by the authors.

Authorship

All named authors meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authors’ Contributions

JCG, ZSL and YXG participated in the acquisition/collection of data and analysis or interpretation of data. JCG, ZSL, HMC, XMX, YAL, and YXG participated in the analysis or interpretation of data. All authors participated in drafting the publication and/or revising it critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version for submission.

Disclosures

Jiachen Gu, Zongshan Li, Huimin Chen, Xiaomin Xu, Yongang Li, Yaxing Gui declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The current study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital affiliated with the Zhejiang University School of Medicine (SRRSH2017-0075A). Each patient provided written informed consent prior to be included in the study. The study was performed in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Data Availability

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Chen XQ, Mobley WC. Alzheimer disease pathogenesis: insights from molecular and cellular biology studies of oligomeric Abeta and tau species. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:659. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bharadwaj PR, Dubey AK, Masters CL, Martins RN, Macreadie IG. Abeta aggregation and possible implications in Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:412–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00609.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sadigh-Eteghad S, Sabermarouf B, Majdi A, Talebi M, Farhoudi M, Mahmoudi J. Amyloid-beta: a crucial factor in Alzheimer's disease. Med Princ Pract. 2015;24:1–10. doi: 10.1159/000369101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ding X, Zhang S, Jiang L, Wang L, Li T, Lei P. Ultrasensitive assays for detection of plasma tau and phosphorylated tau 181 in Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl Neurodegener. 2021;10:10. doi: 10.1186/s40035-021-00234-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janelidze S, Mattsson N, Palmqvist S, et al. Plasma P-tau181 in Alzheimer's disease: relationship to other biomarkers, differential diagnosis, neuropathology and longitudinal progression to Alzheimer's dementia. Nat Med. 2020;26:379–386. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0755-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perrone D, Fuggetta MP, Ardito F, et al. Resveratrol (3,5,4'-trihydroxystilbene) and its properties in oral diseases. Exp Ther Med. 2017;14:3–9. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.4472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Navarro G, Martinez-Pinilla E, Ortiz R, Noe V, Ciudad CJ, Franco R. Resveratrol and related stilbenoids, nutraceutical/dietary complements with health-promoting actions: industrial production, safety, and the search for mode of action. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2018;17:808–826. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koushki M, Amiri-Dashatan N, Ahmadi N, Abbaszadeh HA, Rezaei-Tavirani M. Resveratrol: a miraculous natural compound for diseases treatment. Food Sci Nutr. 2018;6:2473–2490. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marambaud P, Zhao H, Davies P. Resveratrol promotes clearance of Alzheimer's disease amyloid-beta peptides. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:37377–37382. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508246200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Savaskan E, Olivieri G, Meier F, Seifritz E, Wirz-Justice A, Muller-Spahn F. Red wine ingredient resveratrol protects from beta-amyloid neurotoxicity. Gerontology. 2003;49:380–383. doi: 10.1159/000073766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krikorian R, Nash TA, Shidler MD, Shukitt-Hale B, Joseph JA. Concord grape juice supplementation improves memory function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Br J Nutr. 2010;103:730–734. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509992364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butterfield DA, Halliwell B. Oxidative stress, dysfunctional glucose metabolism and Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2019;20:148–160. doi: 10.1038/s41583-019-0132-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang WJ, Zhang X, Chen WW. Role of oxidative stress in Alzheimer's disease. Biomed Rep. 2016;4:519–522. doi: 10.3892/br.2016.630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Markesbery WR. The role of oxidative stress in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:1449–1452. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.12.1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moloney CM, Lowe VJ, Murray ME. Visualization of neurofibrillary tangle maturity in Alzheimer's disease: a clinicopathologic perspective for biomarker research. Alzheimers Dement. 2021 doi: 10.1002/alz.12321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prabhu V, Srivastava P, Yadav N. Resveratrol depletes mitochondrial DNA and inhibition of autophagy enhances resveratrol-induced caspase activation. Mitochondrion. 2013;13:493–499. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang T, Chi Y, Ren Y, Du C, Shi Y, Li Y. Resveratrol reduces oxidative stress and apoptosis in podocytes via Sir2-related enzymes, Sirtuins1 (SIRT1)/peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma co-activator 1alpha (PGC-1alpha) axis. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:1220–1231. doi: 10.12659/MSM.911714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang F, Wang YY, Liu H, et al. Resveratrol produces neurotrophic effects on cultured dopaminergic neurons through prompting astroglial BDNF and GDNF release. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:937605. doi: 10.1155/2012/937605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang F, Wang H, Wu Q, et al. Resveratrol protects cortical neurons against microglia-mediated neuroinflammation. Phytother Res. 2013;27:344–349. doi: 10.1002/ptr.4734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rahman MH, Akter R, Bhattacharya T, et al. Resveratrol and neuroprotection: impact and its therapeutic potential in Alzheimer's disease. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:619024. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.619024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moussa C, Hebron M, Huang X, et al. Resveratrol regulates neuro-inflammation and induces adaptive immunity in Alzheimer's disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2017;14:1. doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0779-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thaung Zaw JJ, Howe PRC, Wong RHX. Sustained cerebrovascular and cognitive benefits of resveratrol in postmenopausal women. Nutrients. 2020;12:2. doi: 10.3390/nu12030828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turner RS, Thomas RG, Craft S, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of resveratrol for Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2015;85:1383–1391. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fang Y, Su Z, Si W, Liu Y, Li J, Zeng P. Network pharmacology-based study of the therapeutic mechanism of resveratrol for Alzheimer's disease. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2021;41:10–19. doi: 10.12122/j.issn.1673-4254.2021.01.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma T, Tan MS, Yu JT, Tan L. Resveratrol as a therapeutic agent for Alzheimer's disease. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:350516. doi: 10.1155/2014/350516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fox NC, Black RS, Gilman S, et al. Effects of Abeta immunization (AN1792) on MRI measures of cerebral volume in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2005;64:1563–72. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000159743.08996.99. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Dubois B, Masure S, Hurtenbach U, et al. Resistance of young gelatinase B-deficient mice to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and necrotizing tail lesions. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1507–1515. doi: 10.1172/JCI6886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leppert D, Leib SL, Grygar C, Miller KM, Schaad UB, Hollander GA. Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-8 and MMP-9 in cerebrospinal fluid during bacterial meningitis: association with blood-brain barrier damage and neurological sequelae. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:80–84. doi: 10.1086/313922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bastianetto S, Menard C, Quirion R. Neuroprotective action of resveratrol. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852:1195–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Porquet D, Grinan-Ferre C, Ferrer I, et al. Neuroprotective role of trans-resveratrol in a murine model of familial Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42:1209–1220. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen GF, Xu TH, Yan Y, et al. Amyloid beta: structure, biology and structure-based therapeutic development. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2017;38:1205–1235. doi: 10.1038/aps.2017.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pasinetti GM, Wang J, Ho L, Zhao W, Dubner L. Roles of resveratrol and other grape-derived polyphenols in Alzheimer's disease prevention and treatment. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852:1202–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yan Y, Yang H, Xie Y, Ding Y, Kong D, Yu H. Research progress on Alzheimer's disease and resveratrol. Neurochem Res. 2020;45:989–1006. doi: 10.1007/s11064-020-03007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosso SM, van Herpen E, Pijnenburg YA. Total tau and phosphorylated tau 181 levels in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with frontotemporal dementia due to P301L and G272V tau mutations. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1209–1213. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.9.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaminari A, Giannakas N, Tzinia A, Tsilibary EC. Overexpression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) rescues insulin-mediated impairment in the 5XFAD model of Alzheimer's disease. Sci Rep. 2017;7:683. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00794-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.