Abstract

Introduction

Critical gaps exist in the understanding of the continuum of multiple sclerosis (MS) progression, particularly with regard to the patient experience prior to and during the transition from relapsing–remitting MS (RRMS) to secondary-progressive MS (SPMS) stages. To date, there are no clear diagnostic criteria in the determination of the clinical transition. We report here the use of patient experience data to support the development of a qualitative conceptual model of MS that describes the patient journey of transition from active-relapsing disease to progressive MS.

Methods

The study used a single-encounter, multicenter, qualitative observational study design that included a targeted literature review and individual, in-depth interviews with adult patients with a clinically confirmed diagnosis of SPMS and their adult care partners. Descriptions of symptoms and impacts of RRMS and SPMS were extracted from the literature review and used to support development of the interview guide and conceptual model.

Results

Participants described a slow progression in terms of change in symptoms over time, including both the development of new symptoms and the worsening of existing symptoms.

Conclusions

The conceptual model of the transitionary period from RRMS to SPMS expands the current understanding of the progression of MS from the patient and care partner perspectives.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40120-021-00265-0.

Keywords: Multiple sclerosis, Primary-progressive, Secondary-progressive, Relapsing–remitting, Transition process, Patient-centered outcomes

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Critical gaps exist in understanding the continuum of multiple sclerosis (MS) progression, particularly specific to the patient experience prior to and during the transition from relapsing–remitting MS (RRMS) to secondary-progressive MS (SPMS). |

| This study explored patient and care partner perspectives of MS progression, emphasizing the understanding of transition from RRMS to SPMS. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| The developed conceptual model depicts the patient journey, including both progression and the impact of progression, and may be useful in helping to determine factors that lead to the transition point of SPMS. |

| Consideration of the patient experience through the transition process by elucidating patient views, concerns, and preferences may be useful to health care providers and other stakeholders as they seek to provide timely and relevant care to patients with SPMS. |

| Feedback from patients and care partners in this qualitative study underscores the need for availability of a tool to identify early signs of MS progression and further augment patient-clinician communication related to disease state and management. |

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a progressive central nervous system (CNS) disease affecting a wide range of functions. Throughout the disease continuum, some symptoms tend to appear, disappear, and reappear [1], while others remain for long periods. Although the progression of MS is unpredictable, its phenotypes can be categorized as relapsing or progressive. These categories, however, do not provide information about the ongoing disease process. Clinical evidence of disease progression is often independent of relapses over a period of time in patients who have a progressive disease course. Progressive disease, either primary-progressive MS or secondary-progressive MS (SPMS), may remain relatively stable over periods of time, during which progression must be determined by patient history or objective measure of change (i.e., evidence of lesions). Both relapsing and progressive disease may be characterized by severity of signs and symptoms, relapses, worsening disability, and impairment [2], but these characteristics do not provide sufficient evidence of active disease course. In fact, incomplete recovery from acute relapse can be indicative of disease worsening over time. SPMS is diagnosed retrospectively via history of gradual worsening after an initial relapsing disease course, with or without acute exacerbations during the progressive course [2]. Despite this characterization of the clinical course of MS, critical gaps exist in understanding the continuum of MS progression, particularly specific to the patient experience prior to and during the transition from relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) to SPMS. To date, no clear diagnostic criteria exist that define the clinical transition.

In this study, we explored patient and care partner perspectives of MS progression, emphasizing the understanding of transition from RRMS to SPMS. Patient experience data were used to develop a qualitative conceptual model of MS describing the patient journey of transition from active-relapsing disease to progressive MS, integrated clinical and psychological aspects of health outcomes, and proposed specific relationships between the different health outcomes. By exploring the transition process from the perspective of both the patient and the care partner, the model may improve patient outcomes through identifying factors that lead to the transition from RRMS to SPMS.

Methods

Study design

The study used a single-encounter, multicenter, qualitative observational study design including a targeted literature review and individual, in-depth interviews with dyads of adult patients with a clinically confirmed diagnosis of SPMS and their adult care partners. Care partner was defined as a nonmedical provider who is in daily or near daily contact with the patient. The term care partner was used instead of care giver to emphasize the inclusive role of these individuals and the autonomous participation of the patient receiving care. The interview component of this study was approved by the RTI Institutional Review Board (Federal-Wide Assurance #3331). The study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. Participants provided written informed consent to participate and for publication of study results. A convenience sample was employed in this study, as supported by 2020 Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidance [3] for the collection of patient experience data, and concept saturation, the point at which interviews yield no new information, was monitored and documented using a saturation grid. Participants were identified via medical record review by physician investigators. Inclusion criteria required patients be aged 35–65 years, have a care partner 18 years or older, and have a clinician-verified diagnosis of MS for at least 8 years with progression. Additionally, patients had to have confirmed accumulation of disability either through an Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score ≥ 3 or an equivalent clinical presentation based on physician assessment. Participants were excluded if they self-reported a concurrent diagnosis of any other neurologic or neuromuscular disease. Participants meeting eligibility criteria were scheduled for telephone interviews. The semistructured interviews were conducted to capture feedback describing the patient journey of transition from RRMS to SPMS. Interview transcripts were prepared that underwent a structured quality review.

Literature Review and Interview Structure

A literature search of the MEDLINE database (Electronic Supplementary Material Table S-1), targeting publications since 2007, identified 145 abstracts, from which 29 articles were selected for full-text review. The review focused on identification of concepts deemed most meaningful from the patient and care partner perspective. Concepts were extracted from 11 articles, informing development of a semistructured interview guide [4–14].

The use of semistructured guides allows flexibility to follow the conversation and gather rich data. The overarching concepts included within the guides were explored in depth; however, the interviewers followed the natural flow of conversation to allow participants to fully express their ideas and experiences. Interviews explored high-level concepts, including the awareness of change in disease status, reaction to the new diagnosis, the reality of living with progressive disease, health care experiences surrounding transition, and thoughts related to the future. All interviews were conducted by independent researchers with extensive experience in leading qualitative research who have conducted interviews across a wide variety of therapeutic areas and who were unaffiliated with the participants’ health care.

Data Analysis and Conceptual Model Building

Interviewer field notes and transcripts were used to analyze interview data. Standard qualitative analysis methods were used to identify, characterize, and summarize patterns found in the interview data. Constant comparative analysis [3] methodology was utilized. Dominant trends were identified in each interview and compared across the results of other interviews to generate themes or patterns in the way participants described their experiences. Concepts gleaned from interviews, in conjunction with the targeted literature review, were used to develop a conceptual model of disease progression in MS. The model included key concepts, definitions, and information on how concepts are related to one another and to key outcomes of interest.

Results

Targeted Literature Review

Descriptions of symptoms and impacts of RRMS and SPMS were extracted from the literature. The synthesized results of the review that were used to support development of the interview guide and conceptual model are described here. Symptoms of MS are variable and unpredictable but may include fatigue, pain, loss of function or feeling in the legs, loss of balance and coordination, slurring of speech, loss of bowel or bladder control, sexual dysfunction, loss of cognitive functioning, and emotional changes [4, 13]. These symptoms of MS, coupled with the progressive and irreversible functional disability that some patients experience, can have a profound impact on all aspects of patients’ lives. SPMS develops in approximately 85% of those with RRMS within 20 years of onset [5], although recent improvement in treatment options may reduce this frequency. The median time to SPMS transition is consistently reported at around 20 years [8]. Neither imaging criteria nor biomarkers are available to objectively distinguish RRMS from SPMS; therefore, SPMS is diagnosed retrospectively [4]. The transition from RRMS to SPMS is a period of diagnostic uncertainty that may last for several years (3 years on average) [6, 9].

SPMS is characterized by the progressive accumulation of disability over at least 6 months after an initial RR course, with or without acute exacerbations during progression. Patients with SPMS are likely to have higher scores of depression and anxiety, tend to lose emotional control more easily, and demonstrate worse scores on all dimensions of quality of life [10]. Three articles identified in the literature review discussed the patient experience with the transition from RRMS to SPMS [5, 6, 12]. Each of these three UK-based studies were based on qualitative interviews with patients. Consistent themes around patient experiences with transition emerged from all three papers (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of major themes in three published studies on transitioning to secondary-progressive multiple sclerosis

| O'Loughlin et al. [12] | Davies et al. [6] | Bogosian et al. [5] |

|---|---|---|

| • Is this really happening | • Realization | • Maintaining things as usual |

| • Becoming a reality | • Reaction | • Scaling back |

| • A life of struggle | • Reality—living with progressive disease | • Finding alternatives |

| • Brushing oneself off and moving on | • Reality—health care experiences around transition | • Resigning |

| • Recognizing future challenges |

Interviews

A total of 19 in-depth, individual interviews were conducted (patients, n = 10; care partners, n = 9) (Table 2). The mean patient age was 52.2 years, the majority of respondents were female (70%) and Caucasian (60%), and educational status represented a range of levels. Scores on the EDSS ranged from 4 to 7. Most symptoms and impacts were identified following completion of the fourth dyad. With the exception of the impact concept of “rarely leaves the house,” no new concepts were raised following the conclusion of the interview with the seventh dyad. All symptom and impact item concepts identified during the literature review were endorsed by patients with MS and their care partners. These combined results provide further evidence of concept saturation, supporting finalization of the conceptual disease model.

Table 2.

Characteristics of interview participants

| Characteristic | Patients (n = 10) | Care partners (n = 9) | Total (N = 19) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (range), years | 52.5 (35–63) | 46.2 (30–64) | 49.5 (30–64) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 3 (30.0) | 3 (33.3) | 6 (31.6) |

| Female | 7 (70.0) | 6 (66.7) | 13 (68.4) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Hispanic | 3 (30.0) | 2 (22.2) | 5 (26.3) |

| White | 6 (60.0) | 7 (77.8) | 13 (68.4) |

| Mixed | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.3) |

| Education, n (%)a | |||

| Some high school | 1 (10.0) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (10.5) |

| High school or equivalent (e.g., GED) | 1 (10.0) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (10.5) |

| Some college but no degree | 3 (30.0) | 2 (22.2) | 5 (26.3) |

| Associate degree/technical school | 1 (10.0) | 2 (22.2) | 3 (15.8) |

| College degree | 3 (30.0) | 1 (11.1) | 4 (21.1) |

| Professional or advanced degree | 1 (10.0) | 2 (22.2) | 3 (15.8) |

| EDSS score, n (%) | |||

| 4 | 2 (20.0) | N/A | 2 (20.0) |

| 4.5 | 2 (20.0) | N/A | 2 (20.0) |

| 5 | 1 (10.0) | N/A | 1 (10.0) |

| 5.5 | 1 (10.0) | N/A | 1 (10.0) |

| 6 | 0 (0.0) | N/A | 0 (0.0) |

| 6.5 | 1 (10.0) | N/A | 1 (10.0) |

| 7 | 1 (10.0) | N/A | 1 (10.0) |

| Clinical presentation based on physician assessment, n (%)b | |||

| Ability to walk, bowel and bladder | 1 (10.0) | N/A | 1 (10.0) |

| Ability to walk, coordination, speech and swallowing, bowel and bladder, visual disturbance | 1 (10.0) | N/A | 1 (10.0) |

| Current medications to treat MS, n (%)c | |||

| Oral | |||

| One | 1 (10.0) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (10.0) |

| Two | 1 (10.0) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (10.0) |

| Three | 1 (10.0) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (10.0) |

| Four | 3 (30.0) | 2 (22.2) | 3 (30.0) |

| Injectable medications | |||

| One | 2 (20.0) | 2 (22.2) | 2 (20.0) |

| Infused medications | |||

| One | 4 (40.0) | 3 (33.3) | 4 (40.0) |

| Relationship of care partner to patient with MS, n (%)a | |||

| Fiancé | N/A | 1 (11.1) | 1 (11.1) |

| Spouse | N/A | 4 (44.4) | 4 (44.4) |

| Paid care partner | N/A | 4 (44.4) | 4 (44.4) |

| Duration of care by care partner to MS patient, mean (range), years | |||

| Total | N/A | 11.0 (4–21) | 11.0 (4–21) |

| With dyad patient | N/A | 9.6 (2–21) | 9.6 (2–21) |

EDSS Expanded Disability Status Scale, GED general education development, MS multiple sclerosis, N/A not applicable

aPercentages do not equal 100 due to rounding

bIn the absence of EDSS, equivalent clinical presentation included assessment of the following: ability to walk, coordination, speech and swallowing, touch and pain, bowel and bladder, visual disturbance, cognition, and other related neurologic signs or symptoms

cCare partner report of patient current medication use was identical, with only information from nine care partners included; therefore, total reflects the overall number of medications per category per patient

RRMS Diagnosis and Symptoms

While a variety of symptoms and impacts were noted prior to transition, fatigue was the symptom most predominantly reported by interview participants (73.7%). Additional symptoms that were highly endorsed (reported by at least 50% of respondents) included bladder incontinence, problems walking, numbness/tingling in hands and feet, and spasms (Table 3). The most commonly reported impacts were professional (i.e., the need to stop working) and emotional; both of these impacts were endorsed by 52.6% of interview participants (Table 4). Participants noted that the need to stop working resulted from overwhelming fatigue as well as cognitive impacts. Participants also expressed functional, social, and emotional impacts due to RRMS. The most commonly reported functional impacts included those related to physical activity and mobility (47.4%). Other functional impacts reported by at least 20% of respondents included those related to hobbies or recreational activities and the ability to engage in or complete household chores. Impacts specific to social relationships were reported by 47.4% of participants, with impacts specific to family life also reported (31.6%).

Table 3.

Sample quotes from participants specific to relapsing–remitting MS symptoms

| Participant | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Fatigue | |

| Patient | Basically, I would wake up feeling a little tired, more than usual, and some days I had a little worse, but that's when I just started noticing, too, that I would wake up, or not wanting to wake up as much |

| Care partner | [Fatigue] was one of the first early symptoms. We actually went to a concert before she had been diagnosed and she fell asleep during a live concert, which we thought was a little unusual until we found out later on. She was just tired all the time and could fall asleep literally anywhere, anytime |

| Incontinence (bowel, bladder) | |

| Patient | Constantly having to pee and couldn't hold it really. Like let's say right now, if I needed to go to the restroom, and I would get up and sometimes before I even got there, I would pee a little on myself, and it's like, 'What?' Like I had no control holding it, so if I had felt that I had to go, I had to go then and there. I couldn't wait |

| Care partner | A little bit in the relapsing–remitting phase, I think… I think she started to experience some of that [both bowel and bladder incontinence] |

| Numbness/tingling in hands/feet | |

| Patient | It was like all the way down the right side. Like I was cut in half and the whole right side is numb. Feet, hands, arms, elbows, whatever, face. I had like, uh, drooping lip kind of like Elvis, you know. Uh, that was going on and I didn't know what was going on until other people told me that was going on |

| Care partner | She talked about numbness and tingling, uh, that she experienced. I don't think she had the numbness and tingling literally all the time, but she would experience it whether or not she was in relapse or in remission. But I think she experienced it more frequently during the relapses |

| Stiffness, spasms, tremor | |

| Patient | My legs will lock up, and also I'll have like really [bad] back spasms, and then my hands will lock up… Even for a simple walk from where I live in my apartment to my mailbox, which is at least a good 800 steps away from where I live to my mailbox. That walk would be the most excruciating pain for me because my back will lock up to the point that I'm just stiff as a board, waiting for it to calm down |

| Care partner | Definitely a tremor. Her left leg, even to this day, if she puts it in a certain position, it will just start bouncing. The clonus will cause it to just keep going until she moves it or literally stops it with her other hand |

| Visual/hearing/speech problems | |

| Patient | My vision was looking so blurry to the point that… like luckily now, I have good eyedrops for my eyes… Like literally there are times when I can't see for nothing, ma'am. Even without the eyedrops and stuff, I still see it blurry |

| Patient | There are time times that when I have trouble saying words or just being able to think of how words are said. Hearing, uh, my wife would say I have selective deafness |

| Care partner | Some vision problems, double vision I think it was |

| Mood swings (irritability, depression) | |

| Patient | I hate to admit this. Yeah, there's times too that I would even push… all my family away because of my mood, and they understand that it's because of my MS. When it comes to depression, I try my best not to let it get to me and not to get the best of me. But yes, there are times that… I'll have depression. But the mood swings is what I'm like, 'Wait a minute. Why am I feeling this way?'… I get so angry. Then I get so sad. And then it's like 'Oh my God. What's going on with me?' |

| Care partner | Just like mood swings. Like bipolar-ish kind of mood swings. That I couldn't understand where they were coming from and now my current understanding is that that's not so uncommon with MS |

| Cognitive dysfunction | |

| Patient | I mean, I was vice president at a bank and I just couldn't even get it straight anymore. I used to manage pension plans and 401 K plans, and I couldn't even… I got to the point where I couldn't balance my own checkbook… I can remember 10 years ago but I can't remember 10 min ago |

| Care partner | She's a very smart woman who had a responsible job and dealt with a lot of different people and different things and that all just kind of slowed down |

| Problems with walking, coordination, balance | |

| Patient | It [weakness] was [in] my left leg. I'd say within 2 to 3 years, [I] was dragging it really bad with a walker. I'd have periods where I'd get better. I was in a wheelchair, and I came back out of the wheelchair with a walker. I'd go walk with a cane, but then I'd go back to a walker |

| Care partner | As I recall, it first started affecting her walking. She couldn't walk quite as far as she used to. It wasn't like it was like boom, but it would just slowly gather up over time. It would get a little worse and worse to where she was like unsteady. And so there was the transition to a cane, to a quad cane, to a walker |

| Temperature sensitivity or regulation difficulty | |

| Patient | Well I did get cold very easy, but myself… it could have been like maybe, let's say, 70 degrees outside and I would carry a blanket with me, like a small blanket, just because I do get cold very easy |

| Care partner | Yes, definitely temperature sensitivity. The relapses all seem to center around her getting too hot. So, yeah, the heat just… like, any level of additional heat beyond a certain point causes her discomfort. And then, if it is sustained, that seems to have been what triggered the relapses primarily |

Participants also reported other symptoms, including cognitive dysfunction, dizziness, paralysis/numbness, reduced interest in or ability to engage in sex, sleep problems, hypersensitivity or reduced sensitivity of skin, and nerve or musculoskeletal pain

Table 4.

Sample quotes from participants specific to relapsing–remitting MS impacts

| Participant | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Work or school | |

| Patient | I can say sometimes in the morning, when I just wasn't like up to par with the day. It just depend[ed] on the way I felt, if it was like a better day or it wasn't such a great day, I would kind of call-in like the morning half of the day, if not sometimes I wouldn't be able to go in |

| Care partner | She was able to continue working for about 3 years or so after diagnosis, and then she had to stop. What she thought was only going to be a temporary disability was turned into permanent disability. But I think a lot of that was the cognitive issues. She worked for a bank with large sums of money, and they want you to be accurate with that stuff |

| Physical activity/mobility (walking, standing, stairs, carrying or lifting heavy items) | |

| Patient | Uh, stairs can sometimes be an issue, particularly late at night. Uh, I have to be careful and cognitive of if I'm carrying something |

| Care partner | Her walking, her coordination in general, and her strength seemed to go down sort of quickly |

| Household chores | |

| Patient | I couldn't keep my house clean like I used to. I was very active when I was younger, constantly cleaning my house. It had to always be done. And it impacted that because I would be too tired to dust and mop. And I just didn't feel myself as far as like keeping up with my house the way I used to. I was the type that, it doesn't matter whether somebody came or not, I had to mop and broom and I had to scrub my toilets like every other day. And it got hard, to the point where it was hard to even do it once a week. So as far as that, I mean I think that's my main thing, that I couldn't do things for myself |

| Hobbies/recreational activities | |

| Care partner | As everything gets worse and worse, it's harder to do things. So you just can't go out and do what you used to do. The company I work for used to… well, they still do… but they have a family night, company night at Disneyland, Universal Studio, different places like that, and we used to go. We'd ride the rides and without, do the whatever it was. Then she slowly got to where she really couldn't do the rides, but my kids were young enough to still go, so I'd ride with some of them on them. Other times I'd wait with her |

| Social relationships | |

| Patient | The worse I got, how quickly friends couldn't handle it and left… They just didn't know what to say or how to deal |

| Care partner | People who know him just, you know, they understood that sometimes he would get irritable and they just accepted that. But I think, people who didn't know him, and if they didn't understand what was going on with him, probably just didn't reach out to him. So it probably did impact forming new relationships, but not current relationships |

| Family life | |

| Patient | My kids would tell me, 'Let's go here,' and I'd be like, 'Oh, I'm just too tired. I don't feel like it.' And I feel more like a burden to them. So it affected me with my kids, as [far as] spending time, my kids and grandkids |

| Care partner | It made it more difficult to do certain things because she'd have to use a cane and stuff. But the kids were very tolerant. They understood it. Now when I ask them, they really don't remember her without MS |

| Self-esteem | |

| Patient | I kind of got a little depressed from that, just because it was like, 'Really? I can't even care for myself.' Like, I should be able to help my daughters take care of their kids and I couldn't even do that. It was the other way around, where they had to help me take care of my house, myself. As a matter of fact, one of my daughters had moved in and it just… Like I told her, I don't see that it's fair. You're here and you're still having to pay for childcare because I can't care for my own grandkids. Now that I'm not working, I should've been able to watch them for you. So it made me feel… [sigh] Well I guess the only word what I really felt was useless |

| Emotional impacts | |

| Patient | Not knowing whether it would throw me into a relapse was really frustrating and concerning. So I had a lot of fear of the unknown because things seemed really erratic |

| Care partner | It was probably more so the anxiety around knowing that she had this thing and there was, you know, basically no way to cure it. Probably, that was the most profound effect on her |

Participants also reported other impacts to activities of daily living involving dressing or eating and intimate relationships

Disease Progression Diagnosis

Sample participant reactions to the news of progression can be found in Table 5. Participants reported receiving minimal or no information about the possibility of progression of MS. While some did not recall any conversation with their physician, other participants noted engaging in minimal discussion with their health care provider (HCP) or doing some research on their own. Participants reported that diagnoses of progression came between 1 and 14 years after initial diagnosis with MS (median, 7–10 years) but noted that little to no information was provided specific to how the diagnosis was made. Participants indicated that, in some instances, the HCP suggested that the disease had likely progressed, but did not offer a clear diagnosis; in other cases, participants shared that HCPs were reluctant to apply an SPMS diagnosis because of potential limitations accessing medication. Participants indicated that most discussions with their HCP occurred over time, as the elapsed time to progression of MS was slow.

Table 5.

Sample quotes from participants on the disease progression diagnosis

| Participant | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Health care provider counsel on progression | |

| Patient | They just said that it was possible that it could get worse, that there was no cures, that there was just medications I can try to make me feel better |

| Patient | I don't really remember being told a lot about progression. I read a lot more about it being a probability actually. But my doctors really were just like, ‘Let's take care of what's going on right now,’ and didn't really talk about, like, the future |

| Reluctance to apply new diagnosis label of SPMS | |

| Patient | After my first neurologist took me off of my medications and he said that all of my brain lesions were in remission, but we would just keep an eye on it. But he said, 'You know, you're probably in the Secondary category.' And I said, 'Secondary?' And then he explained that to me |

| Care partner | My understanding was that there's a reluctance to call it that [SPMS] because there's some sort of problem with insurance covering. Like, it's more difficult to get insurance to cover it if it's labeled that. So, I wasn't actually aware anyone had ever explicitly called it secondary progressive. Um … yeah. I didn't know she had gotten that official diagnosis yet. [laughter] I have still only gone to a couple of her neurology appointments around the time she was trying to get, uh, on disability. And I don't think the words secondary progressive were ever mentioned in the appointments I went to |

| Initial reactions to the news of progression | |

| Patient | I was a very active person, a workaholic, and then when he told me about the progressive and especially that scare, oh that scared me. Even to this day if I'm thinking about it, it still frightens me |

| Care partner | It was really scary. I mean, I think about… I felt really alone. Um, I was worried about him but, you know, I also was worried for myself, like, my older self and, you know, just thinking about everything, like, financial stuff. Like, how do we keep him mobile and independent? How do we afford that? How do we make modifications to our home? And, um, you know, thinking about, you know, and I still do think about the future and what that's going to mean |

SPMS Secondary-progressive multiple sclerosis

Initial reactions to the news of progression ranged from fear and depression to understanding and acceptance. While participants described modifications in treatment throughout the course of their disease, none reported specific treatment modifications made at the time of diagnosis to SPMS. One participant described a conversation about progression in which her physician conveyed being “sorry,” but noted that “there [wasn’t] anything [treatment] available at that time.” Two participants expressed a desire for their physician to approach the discussion more optimistically (with “hope”). Three participants indicated that the initial diagnosis of transition was overwhelming and frightening, and the tone of the conversation was very bleak.

Participants described a slow progression in terms of change in symptoms over time, including both the development of new symptoms and the worsening of existing symptoms. Specifically, participants highlighted worsening fatigue, a decline in mobility/ambulation, and deteriorating cognitive effects. Issues with bladder incontinence (reported by 84% of participants) and cognitive dysfunction were also reported by a majority of the sample (80%). Symptoms of SPMS described by participants were generally more severe than those experienced before the transition and occurred without periods of remission (Table 6). Overall, impacts specific to mobility limitations (89%), household chores (79%), daily activities (58%), and socialization (63%) were highly endorsed (Table 7).

Table 6.

Sample quotes from participants specific to SPMS symptoms

| Participant | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Fatigue | |

| Patient | Now it's like it's hitting me more with frequent tiredness… I'll try to slam at least 3 cups of coffee, and that will not wake me up at all |

| Care partner | He falls asleep a lot, like, you know, in his wheelchair and just kind of nod off, you know, throughout the day, maybe six or seven different times throughout the day. Not every day, but, you know, most days |

| Incontinence (bowel, bladder) | |

| Patient | If I say I got to go, you better get me to toilet because it's just a matter of time… Because sometimes I'll get that warning. There have been times where often I just go… The only thing that helps that is I get Botox in the bladder |

| Care partner | The incontinence and the bowel issues are sort of ever present now, whereas before they would be just, you know, occasional |

| Numbness/tingling in hands/feet | |

| Care partner | He says he has that [numbness and tingling] all the time. He says that will never go away. So, I'm assuming yes. I don't ask him on a daily basis |

| Stiffness, spasms, tremor | |

| Patient | Stiffness in the limbs, uh, pain in the back, uh, tremors hands. There are times at night, I'm lying in a bed and it almost feels like my feet are numb. But I can stand up and it's not like they've fallen asleep or anything, it's just a feeling I get |

| Care partner | Well, she does have leg spasms sometimes. I think those generally happen at night and they sometimes cause her to have problems sleeping |

| Visual/hearing/speech problems | |

| Patient | I'm noticing that now that even my vision now is just becoming so blurry to the point that I need either extra eyedrops or glasses, one of the two |

| Patient | Well, you may be able to tell my speech is not good |

| Care partner | More recently her speech, sometimes she has a little trouble finding a word or just getting the word out once she's realized what it is |

| Mood swings (irritability, depression) | |

| Patient | It was going good until that time [progression]… Then my mood swings would definitely severely change rapidly |

| Care partner | Kind of the same as before [progression], maybe a little bit more so, um, so just sort of depression around not being able to do the things she would like to do. Um, and, you know, frustration at that same thing |

| Problems with walking, coordination, balance | |

| Patient | Before that, I could manage my wheelchair. I'd be able to pull myself up, and then at the 10-year mark, literally I lost the ability to sit up straight. If I bend over, I can't sit back up |

| Care partner | It's hard for her to stand up and walk around. She has a walker. Sometimes she loses her balance, every now and then |

| Temperature sensitivity or regulation difficulty | |

| Patient | I get very cold very, very quickly. And then if I get cold, I'm kind of screwed because it takes me a while to heat up |

| Care partner | Very minor changes in temperature really affect her. She doesn't do good in cold at all |

Participants also reported other symptoms, including cognitive dysfunction, dizziness, paralysis/numbness, reduced interest in or ability to engage in sex, sleep problems, hypersensitivity or reduced sensitivity of skin, and nerve or musculoskeletal pain

Table 7.

Sample quotes from participants specific to SPMS impacts

| Participant | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Work or school | |

| Patient | I ended up quitting my job in October 2015. So that's when I really, I knew for certain that things were not good because I really was experiencing a lot of cognitive issues that I hadn't experienced before and really erratic emotions and things were just really… they seemed weird to me |

| Care partner | She did have to stop working. She always performed very well at work. She got several merit-based raises during her career at her last employer and then… it's almost… Well, alongside the progression of all of her symptoms, she started getting poor performance reviews. And then, that was sort of creating a feedback with where she had more anxiety about work and performed worse, and we sort of realized at that point that she was… her disease was preventing her from performing her job functions |

| Physical activity/mobility (walking, standing, stairs, carrying or lifting heavy items) | |

| Patient | Carrying, my arms are very weak. I can't go to the store or anywhere for very long |

| Care partner | It definitely has affected her walking ability. We have a two-story house and the stairs have become much more difficult for her. It's pretty much, if she comes downstairs, she kind of plans ahead, gets it all together, comes downstairs once and does what she needs to, so she only has to do the stairs once and then back up when she's done and that's about it |

| Household chores | |

| Patient | In my wheelchair, I could wipe down the kitchen counter, do the dishes. I wasn't able to cook, but I could do the dishes, wipe down the kitchen counters, clean the bathroom counters, all from my wheelchair… You know, do laundry and stuff like that. Bend over and pick up the dog food bowl. But for whatever reason, at that 10-year [mark], that's it. It all stopped |

| Hobbies/recreational activities | |

| Patient | I do miss, uh, being able to sports. I do miss, um, like my kid's going to play soccer. He played soccer last year. I do miss the [inaudible] be out there and be like practice with him. You know show him things |

| Social relationships | |

| Patient | It's just harder to do everything so I never want to talk on the phone because I have difficulty talking. So I don't keep in touch with people on the phone anymore |

| Care partner | I mean, we can still have people over to the house, and they understand her difficulty and everything. But we just can't go to other people's houses |

| Family life | |

| Patient | I have a 14-year-old daughter [laughter] and so it's sometimes it is very hard for me to… I don't want to say deal with her, but I feel more like a child than she is sometimes |

| Care partner | She doesn't like to go out with her family because she doesn't like to slow them up. So there's just things that she just did before that she can't do now. Or let's say, like her family will try to take her somewhere, and they'll kind of slow down for her, and they're doing it out of kindness or courtesy or so, but it bothers her |

| Self-esteem | |

| Care partner | She tells me sometimes that, you know, she just wishes she could do things like normal people. She wishes she could still do the things she used to do, um, that sort of thing. And she talks about, she talks about being a burden to me and wishing she could help earn money for the family and those sorts of things |

| Emotional impacts | |

| Patient | I just would cry… What is it called? I don't remember. And not because I was sensitive or anything. Just because I want… my body just wants to cry, you know. We can have a conversation, I'm not happy with what you said, and I would cry. I'd be talking and I'd just start crying |

| Care partner | He gets frustrated when, um, when he wants to be able to do something and it's difficult for him. Um, or when he feels like he's not capable… just I think the emotional impacts or impact is what his future looks like or how long he's going to live… he worries about being a burden to the family |

Participants also reported other impacts to activities of daily living involving dressing or eating and intimate relationships

Care partners described MS as having both a physical and emotional toll on their own lives as they tried to assist and respond to patient needs, while reminding themselves to be patient and understanding. Care partners commented on challenges they encountered in physical aspects of care relating to assisting in dressing and frustration or disappointment in the difficulty of finding places to take the patient outside of the home. Paid care partners wanted to ensure they had accomplished enough for the patient during the limited time they were in the home, noting that sometimes it was hard to get to everything if the patient was having a difficult day. Finally, familial care partners described the fear of the unknown, fear of what was going to happen next, and uncertainty as to whether they would be equipped to continue to care for the patient.

Conceptual model

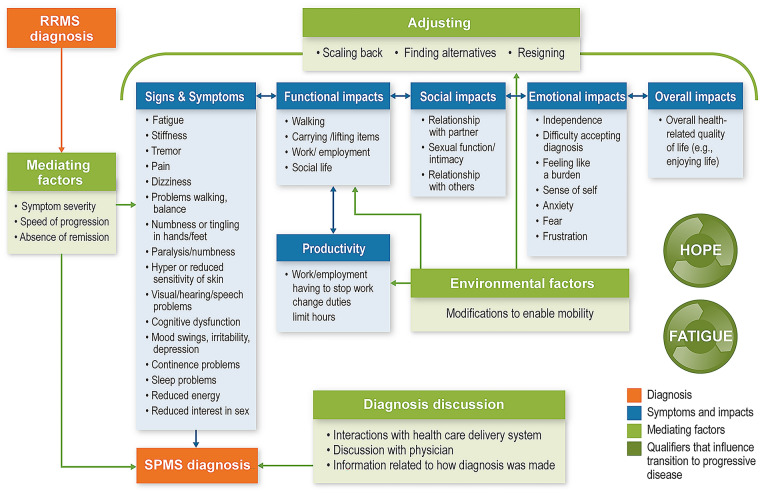

Data from the targeted literature review and participant interviews were used to build the conceptual model (Fig. 1). Participant feedback confirmed the continuum of interrelated concepts as hypothesized from the literature and expert review. Participant responses informed minor changes to the preliminary model. Specifically, the absence of periods of remission was added to mediating factors. Descriptions of emotional impacts were refined to add descriptive terms related to broader concepts of independence and sense of self. Impacts specific to social functioning were expanded, and additional descriptions of concepts raised by participants were included. Productivity was called out and further defined by aspects related to work and employment impacts.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model of transition to SPMS. RRMS Relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, SPMS secondary-progressive multiple sclerosis

Discussion

The key milestone of this research included the development and refinement of a qualitative conceptual disease model. Conceptual model development serves as the foundational basis to identify and refine concepts of interest from an inclusive stakeholder perspective and demonstrates interdependent relationships that depict both disease symptoms and impacts and the additional factors that may influence overall well-being. The model integrated clinical and psychological aspects of health outcomes and proposed specific relationships between the different components. The model depicted the patient journey, including both progression and the impact of progression, and may be useful in helping to determine factors that lead to the transition point of SPMS. In evaluating the effect of therapy, the model provided the rationale for identifying outcomes of interest that are both clinically relevant and meaningful to patients and can provide further support during regulatory decision making for product approval and labeling [15]. This model serves to fill a gap in the literature, where qualitative work regarding the transition from RRMS to SPMS has been limited to small studies conducted in the UK [5, 6, 12]. A recently published article [16] described a mixed-methods approach, including qualitative interviews with 32 patients and 16 neurologists in the USA and Germany as well as quantitative analysis of real-world observational data from 3294 individuals with MS. The study explored and characterized key symptoms and impacts associated with the transition from RRMS to SPMS to support development of a clinical tool to support early evaluation of signs of progressive disease in a standardized manner. This study reinforced our own findings that the transition period is associated with impacts to ambulation or motor functions, daily activities, and employment. The conceptual model presented here serves as a basis for furthering understanding and fostering improved communication between HCPs and their patients by providing insight into patient views, concerns, and preferences within the context of managing the transition to SPMS.

The interviews confirmed the continuum of interrelated concepts. Prior to transition, fatigue was the symptom most predominantly reported by participants, and this symptom significantly impacted patients’ ability to maintain employment. Upon transition, symptoms of fatigue, symptoms related to mobility, issues with incontinence, and cognitive dysfunction continued to be important to patients. Participants especially noted impacts to mobility limitations, daily activities, and socialization. Care partner reports were noted to be particularly valuable with regard to providing information on cognitive impairment and mood changes, two concepts related to MS about which patients may have had less objective insight and for which care partner reports offered an essential complement to the patient’s self-report. The slow decline over time was described as a difficult experience for patients, with participants noting fears related to future impacts as well as lack of available treatment options. Participants also reported a lack of communication about the possibility of progression of MS, which could be improved through educational outreach to patients on the signs of transition that could potentially lead to earlier diagnosis of progression. Digital tools to improve clinical evaluation and monitoring in patients, such as MSProDiscuss and Floodlight, could also be used to identify early signs of MS progression [17, 18]. Once diagnosed with progression, patient discussions with HCPs regarding their diagnosis were reported to be inconsistent, in terms of both the depth and the quality of information provided, which could have contributed to the fears of life impacts and lack of available treatment options.

Results from the literature review, expert opinion, and interviews supported hypothesized relationships, beginning with the cardinal signs and symptoms of MS that impair function, leading to limitations in work/employment and social life. Similarly, symptoms of MS can impact patients’ independence and cause emotional disturbances. All of these factors may directly impact one’s perceptions of health and health-related quality of life. Key modifiers of progression included the overarching severity of new or worsening symptoms experienced combined with speed of progression and associated age when advanced disease occurs.

Additionally, the availability of support resources, the psychological implications of disease progression, and the availability of care partner support as functional ability declines are all factors that directly influence patients’ perceptions of overall quality of life. Other factors that were described as impacting the patient journey included interactions with HCPs; assistance with navigating therapeutic options and resources for psychological support; and various financial aspects, including navigation of insurance coverage and support for obtaining mobility aids or care partner support and respite care. Patients and families who adjust to and accept the transition to an advanced disease state are bolstered by ongoing interaction and support. These factors can provide them with hope about their ability to manage the symptoms and impacts of MS as well as offer foundational support as these individuals adjust to life and lifestyle impacts that occur as part of disease progression. Variability in patient experiences may be influenced by the patient’s specific clinical site or by the motivation of the patient to actively participate in patient advocacy organizations.

A limitation of this study is that the sampling procedure may limit the generalizability of the results. However, the use of a non-probability sampling approach is in alignment with FDA guidance as an appropriate approach for obtaining patient experience data [3]. Additionally, the variability in patient experience may be influenced by the specific clinical site due to the potential for homogeneity in practice at a given site.

Conclusion

The conceptual model of the transitionary period from RRMS to SPMS expands the current understanding of the progression of MS from the patient and care partner perspective. A better understanding of the patient experience through the transition process by elucidating patient views, concerns, and preferences may be useful to HCPs and other stakeholders as they seek to provide timely and relevant care to patients with SPMS, especially given the advanced treatments becoming available for SPMS. The current model provides further support in describing the relationships of symptoms and impacts through progression of disease. Feedback from patients and care partners in this qualitative study underscores the need for availability of a tool to further augment patient-clinician communication related to disease state and management.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the study.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: RTI Health Solutions received funding under a research contract with Novartis Pharmaceuticals to conduct this study and provide publication support in the form of manuscript writing, styling, and submission. Novartis Pharmaceuticals funded the journal’s Rapid Service Fee.

Medical Writing Assistance

The authors thank Brian Samsell of RTI Health Solutions for medical writing assistance. Novartis Pharmaceuticals provided funding for publication support in the form of manuscript writing, styling, and submission.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

All authors declare that they have made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; have drafted or written, or substantially revised or critically reviewed the article; have agreed on the journal to which the article will be submitted; have reviewed and agreed on all versions of the article before submission, during revision, the final version accepted for publication, and any significant changes introduced at the proofing stage; and agree to take responsibility and be accountable for the contents of the article.

Disclosures

Wendy Su is a Novartis Pharmaceuticals employee. Roshani Shah and Patricia A. Russo were employees of Novartis at the time the work was completed. Lauren Bartolome was a post-doc fellow at Thomas Jefferson University providing services to Novartis at the time of this research. Sibyl E. Wray is a paid consultant for Novartis Pharmaceuticals but did not receive compensation for participation in this study. Sandy Lewis and Carla Romano are employees of RTI Health Solutions, an independent nonprofit research organization that does work for government agencies and pharmaceutical companies. Emily Evans was an employee of RTI Health Solutions at the time the work was completed.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The interview component of this study was approved by the RTI Institutional Review Board (Federal-Wide Assurance #3331). This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, and its later amendments. Individuals meeting eligibility criteria provided written informed consent for participation. Participants provided written informed consent for publication of study results.

Data Availability

Data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Kasser SL, Goldstein A, Wood PK, Sibold J. Symptom variability, affect and physical activity in ambulatory persons with multiple sclerosis: understanding patterns and time-bound relationships. Disabil Health J. 2017;10(2):207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lublin FD, Reingold SC, Cohen JA, Cutter GR, Sorensen PS, Thompson AJ, et al. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: the 2013 revisions. Neurology. 2014;83(3):278–286. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Food and Drug Administration. Patient-focused drug development: collecting comprehensive and representative input. Guidance for industry, food and drug administration staff, and other stakeholders. 2020. https://www.fda.gov/media/139088/download. Accessed 12 May 2021.

- 4.Bamer AM, Cetin K, Amtmann D, Bowen JD, Johnson KL. Comparing a self report questionnaire with physician assessment for determining multiple sclerosis clinical disease course: a validation study. Mult Scler. 2007;13(8):1033–1037. doi: 10.1177/1352458507077624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bogosian A, Morgan M, Bishop FL, Day F, Moss-Morris R. Adjustment modes in the trajectory of progressive multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study and conceptual model. Psychol Health. 2017;32(3):343–360. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2016.1268691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies F, Edwards A, Brain K, et al. 'You are just left to get on with it': qualitative study of patient and carer experiences of the transition to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. BMJ Open. 2015;5(7):e007674. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies F, Wood F, Brain KE, et al. The transition to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: an exploratory qualitative study of health professionals' experiences. Int J MS Care. 2016;18(5):257–264. doi: 10.7224/1537-2073.2015-062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doward LC, McKenna SP, Meads DM, Twiss J, Eckert BJ. The development of patient-reported outcome indices for multiple sclerosis (PRIMUS) Mult Scler. 2009;15(9):1092–1102. doi: 10.1177/1352458509106513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giovannetti AM, Giordano A, Pietrolongo E, et al. Managing the transition (ManTra): a resource for persons with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis and their health professionals: protocol for a mixed-methods study in Italy. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8):e017254. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montel SR, Bungener C. Coping and quality of life in one hundred and thirty five subjects with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007;13(3):393–401. doi: 10.1177/1352458506071170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newland PK, Thomas FP, Riley M, Flick LH, Fearing A. The use of focus groups to characterize symptoms in persons with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2012;44(6):351–357. doi: 10.1097/JNN.0b013e318268308b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Loughlin E, Hourihan S, Chataway J, Playford ED, Riazi A. The experience of transitioning from relapsing remitting to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: views of patients and health professionals. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(18):1821–1828. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2016.1211760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reade JW, White MB, White CP, Russell CS. What would you say? Expressing the difficulties of living with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2012;44(1):54–63. doi: 10.1097/JNN.0b013e31823ae471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Hiele K, van Gorp DA, Heerings MA, et al. The MS@Work study: a 3-year prospective observational study on factors involved with work participation in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol. 2015;12(15):134. doi: 10.1186/s12883-015-0375-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA. 1995;273(1):59–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03520250075037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ziemssen T, Tolley C, Bennett B, et al. A mixed methods approach towards understanding key disease characteristics associated with the progression from RRMS to SPMS: physicians' and patients' views. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;38:101861. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2019.101861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baker M, van Beek J, Gossens C. Digital health: Smartphone-based monitoring of multiple sclerosis using Floodlight. https://www.nature.com/articles/d42473-019-00412-0. Accessed 24 June 2021.

- 18.Ziemssen T, Piani-Meier D, Bennett B, et al. A physician-completed digital tool for evaluating disease progression (multiple sclerosis progression discussion tool): validation study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(2):e16932. doi: 10.2196/16932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.