Abstract

T-cell development in the thymus is characterized by changing expression patterns of CD4 and CD8 coreceptor molecules and by changes in CD4 and CD8 gene transcription. In response to T-cell receptor (TCR) signals, thymocytes progress through developmental transitions, such as conversion of CD4+CD8+ (double-positive [DP]) thymocytes into intermediate CD4+CD8− thymocytes, that appear to require more-rapid changes in coreceptor expression than can be accomplished by transcriptional regulation alone. Consequently, we considered the possibility that TCR stimulation of DP thymocytes not only affects coreceptor gene transcription but also affects coreceptor RNA stability. Indeed, we found that TCR signals in DP thymocytes rapidly destabilized preexisting CD4 and CD8 coreceptor RNAs, resulting in their rapid elimination. Destabilization of coreceptor RNA was shown for CD8α to be dependent on target sequences in the noncoding region of the RNA. TCR signals also differentially affected coreceptor gene transcription in DP thymocytes, terminating CD8α gene transcription but only transiently reducing CD4 gene transcription. Thus, posttranscriptional and transcriptional regulatory mechanisms act coordinately in signaled DP thymocytes to promote the rapid conversion of these cells into intermediate CD4+CD8− thymocytes. We suggest that destabilization of preexisting coreceptor RNAs is a mechanism by which coreceptor expression in developing thymocytes is rapidly altered at critical points in the differentiation of these cells.

Precursor cell differentiation in the thymus proceeds via an ordered sequence of developmental events that are best characterized by changes in surface expression of the coreceptor molecules CD4 and CD8 (15, 25). Early thymocyte precursors are CD4−CD8− (double negative), and those that have successfully rearranged and expressed a productive T-cell receptor (TCR) β chain (TCRβ) are signaled to rearrange their TCRα gene locus, to become CD4−CD8lo precursor cells, and to subsequently differentiate into CD4+CD8+ (double-positive [DP]) thymocytes. As a result, most DP thymocytes express assembled αβTCR complexes on their surface (for a review, see reference 18). However, cell surface expression of αβTCR complexes is not sufficient to promote the further differentiation of DP thymocytes into mature CD4+CD8− and CD4−CD8+ single-positive (SP) T cells. Rather, only DP thymocytes with TCRs of appropriate specificity for intrathymic ligands are signaled to further differentiate into CD4+CD8− and CD4−CD8+ SP T cells (2, 3, 9, 30, 35, 36). Thus, each developmental step in the thymus is characterized by changing expression patterns of CD4 and CD8 coreceptor molecules. However, the molecular bases for these changing coreceptor expression patterns during thymocyte development remain to be fully elucidated.

The changes in coreceptor expression that occur during thymocyte differentiation parallel changes in coreceptor transcription (1, 6). However, transcriptional regulation of coreceptor expression may not be the only mechanism utilized by developing thymocytes. It is conceivable that intrathymic differentiation also involves posttranscriptional regulatory mechanisms to effect rapid changes in coreceptor expression patterns in response to intrathymic signals. Indeed, we have previously demonstrated that signals transduced by surface αβTCR complexes on CD4−CD8lo precursor cells block their differentiation into CD4+CD8+ thymocytes by actively destabilizing CD4 and CD8 coreceptor RNAs (33, 34). As a result, expression of both CD4 and CD8 coreceptors was extinguished in these cells, despite ongoing transcription of both coreceptor genes. It is not clear if such posttranscriptional regulatory mechanisms also function in thymocytes beyond the DP stage of development.

Recently, we made the surprising observation that signaled DP thymocytes initially terminated CD8 transcription to become intermediate CD4+CD8− thymocytes regardless of their ultimate lineage fate (E. Brugnera, A. Bhandoola, R. Cibotti, Q. Yu, T. I. Guinter, Y. Yamashita, S. O. Sharrow, and A. Singer, submitted for publication). In other words, signaled DP thymocytes initially converted into intermediate CD4+CD8− thymocytes even when they ultimately differentiated into CD8+ SP T cells. Importantly, we think that it is at this intermediate CD4+CD8− stage of development that lineage determination occurs. In intermediate CD4+CD8− thymocytes, TCR-selecting signals are assessed for their dependence on surface CD8 coreceptor engagements: TCR signals in DP thymocytes that are dependent on CD8 coengagement cease on conversion of DP thymocytes into intermediate CD4+CD8− cells because of decreased surface CD8 coreceptor expression, whereas TCR signals in DP thymocytes that are independent of CD8 coengagements persist on conversion of the cells into intermediate CD4+CD8− thymocytes. As a result, lineage choice is critically affected by the rapidity with which CD4 and CD8 coreceptor expression can be altered in signaled DP thymocytes.

The present study was undertaken to specifically examine the possibility that posttranscriptional, as well as transcriptional, regulatory mechanisms are activated in signaled DP thymocytes so as to rapidly alter their expression of coreceptor molecules and to promote their conversion into intermediate CD4+CD8− cells. Unfortunately, the asynchrony and low efficiency of intrathymic development make it virtually impossible to assess the presence or absence of posttranscriptional regulatory events in thymocytes in vivo. In contrast, DP thymocytes can be efficiently and synchronously signaled in vitro by antibody-induced coengagement of surface TCR and CD2 molecules (5). Such in vitro signaling of DP thymocytes induces them to convert into intermediate CD4+CD8− cells that are indistinguishable from in vivo-generated intermediate CD4+CD8− thymocytes. Using this in vitro system, we found that both transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulatory mechanisms were activated in signaled DP thymocytes to promote their rapid conversion into intermediate CD4+CD8− cells. We suggest that posttranscriptional regulation is an important mechanism by which coreceptor expression is rapidly altered at critical points in thymocyte differentiation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Young adult C56BL/6 (B6) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). Mice deficient in expression of either major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II (II0) or both MHC class II and β2-microglobulin (MHC0) molecules were bred in our own colony from animals originally provided by L. Glimcher and M. Grusby (11). Mice bearing a constitutive CD8.1αβ transgene (pCD2-CD8.1α) were generously provided by E. Robey and B. J. Fowlkes (26).

Cell preparations.

DP thymocytes were obtained from young adult mice by panning single-cell suspensions of thymocytes on anti-CD8 (83-12-5)-coated plates (23). These purified cells were >96% DP thymocytes as assayed by flow-cytometric analysis.

Antibodies.

Monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) with the following specificities were used at concentrations of 5 to 10 μg/ml to coat plates employed in the signaling cultures: TCRβ (H57-597 [17]) and CD2 (RM2-5; PharMingen). MAbs with the following specificities were used for staining: CD4 (GK1.5), CD8.2α (2.43), and CD8.1α (113.16.1).

Culture conditions.

Purified DP thymocytes were either stimulated with plate-bound antibodies to TCRβ and CD2 or cultured in the absence of signaling antibodies for 12 to 16 h (5). Where indicated, stimulated thymocytes were harvested, washed, replated in medium alone, and incubated for an additional 20 h.

Cells were cultured at 37°C, in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere, in complete medium supplemented with 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol and 10% fetal calf serum that had been depleted of endogenous steroids by treatment with 0.5% Norit A charcoal and 0.05% dextran. Where indicated, actinomycin D (10 μg/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) or cycloheximide (10 μg/ml; Sigma) was added to cultures.

Immunofluorescence analysis and flow cytometry.

Three-color immunofluorescence analysis and flow cytometry for CD4, CD8.2α, and CD8.1α were performed by staining cells with phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD4 MAb (GK1.5), fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-CD8.2α MAb (2.43), and biotinylated anti-CD8.1α MAb (113.16.1), followed by Texas red-avidin (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.), as previously described (32). Flow cytometry and electronic cell sorting were performed on a FACStar Plus flow cytometer. Dead cells were excluded from analysis by propidium iodide staining and forward light scatter gating. Data on at least 5 × 104 live cells were collected and analyzed using software designed by the division of Computer Research and Technology at the National Institutes of Health. Two-color sorting of CD4+CD8+ and CD4loCD8− cells was performed on thymocytes from signaling cultures that were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate–anti-CD8 and phycoerythrin–anti-CD4 MAbs.

Northern blot analysis.

Total cellular RNA was prepared from the various cell populations. Equal amounts of RNA were denatured, subjected to electrophoresis on agarose gels, and transferred to nylon membranes (28). Blots were hybridized with a 2.1-kb EcoRI fragment of mouse CD4 cDNA (19), a 0.8-kb XhoI fragment of mouse CD8α cDNA (38), a 0.7-kb HindIII fragment of mouse TCRα cDNA (provided by S. Hedrick, University of California at San Diego), and a 1.3-kb PstI fragment of rat glyceraldehyde-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) cDNA (10). Probes were labeled with 32P by the random prime method. The 18S oligonucleotide 5′-ACGGTATCTGATCGTCTTCGAACC-3′ (37) was labeled by the use of the T4 polynucleotide kinase forward labeling reaction. Blots were exposed overnight and analyzed with a phosphorimager.

Determination of RNA stability and half-life.

DP cells (2.5 × 107) were treated with actinomycin D (10 μg/ml; Sigma) at the beginning of the signaling culture to block new transcription and then either signaled with a combination of anti-TCR and anti-CD2 antibodies or cultured in medium alone. Aliquots of 5 × 106 cells were removed every hour for 4 h. Cytoplasmic RNA from each time point was processed for Northern blot analysis. Densitometric analysis was used to calculate the percentage of specific mRNA remaining after drug treatment. The half-life calculated from these experiments was extrapolated from the logarithmically transformed best-fit line by linear-regression analysis.

Nuclear run-on assays.

Nuclear run-on assays were performed as described elsewhere (4, 24). Briefly, cells (2 × 107 to 5 × 107) were swollen in 0.5 ml of buffer solution (0.5% Nonidet P-40, 10 mM Tris, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, pH 7.4) at 4°C for 5 min, and nuclei were released by Dounce homogenization (Kontes Glass Co., Vineland, N.J.). Nuclei were then incubated for 30 min at 31°C in 0.3 ml of a buffer consisting of 10% glycerol, 10 mM Tris (pH 8), 140 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM MnCl2, 1 mM S-adenosylmethionine, 0.25 mM ATP, 0.25 mM CTP, 0.25 mM GTP and 14.5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol in the presence of 0.30 mCi of [32P]UTP (3,000 Ci/mmol; New England Nuclear) to allow transcript elongation. DNase I (100 U; Worthington Biochemical Corp.) in high-salt buffer (0.5 M NaCl, 50 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM Tris [pH 7.4]) was then added, and the nuclei were incubated for an additional 5 min at 31°C, then lysed with 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and 0.2 mg of proteinase K (Boehringer) for 30 min at 42°C. Nucleic acids were extracted with a mixture of phenol, chloroform, and isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and then precipitated with ethanol. Large-molecular-size RNA was enriched by using Ultrafree-MC filters (PLGC type; Millipore). Total and trichloroacetic acid-precipitable activities were monitored, and approximately 70 to 80% of the 32P activity was incorporated into polyribonucleotides. Equal amounts (3 × 106 to 6 × 106 trichloroacetic acid-precipitable counts per minute) of radioactively labeled RNA were partially digested with 0.2 N NaOH at 4°C for 10 min, neutralized with HEPES, and hybridized to nylon filters (Amersham) which contained immobilized and denatured 2.1-kb EcoRI fragments of mouse CD4 cDNA (0.2 μg per slot), 0.8-kb XhoI fragments of mouse CD8α cDNA (0.2 μg per slot), 1.3-kb PstI fragments of rat GAPDH cDNA (0.2 μg per slot), and Bluescript plasmid alone (EcoRI digested; 0.2 mg per slot). Filters were hybridized for 2 days at 65°C in a buffer containing 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 10 mM EDTA, 0.2% SDS and 0.6 M NaCl. Blots were then washed two times for 45 min each with 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) and 2× SSC–0.1% SDS at 65°C. Blots were exposed overnight and analyzed with a phosphorimager.

RESULTS

Rapid loss of coreceptor RNAs in signaled DP thymocytes.

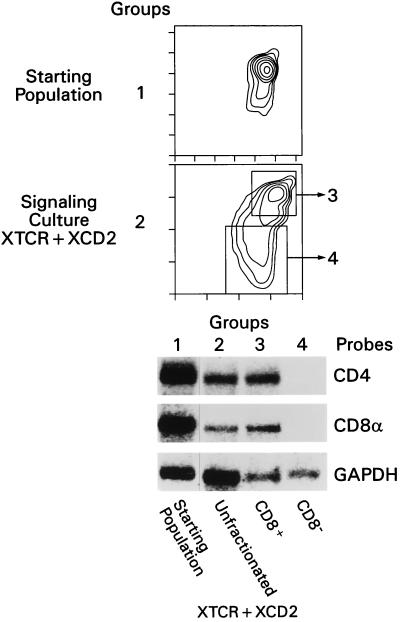

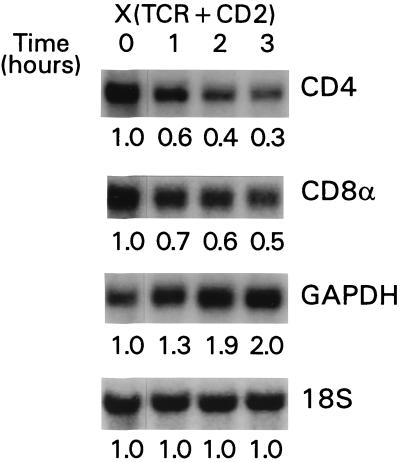

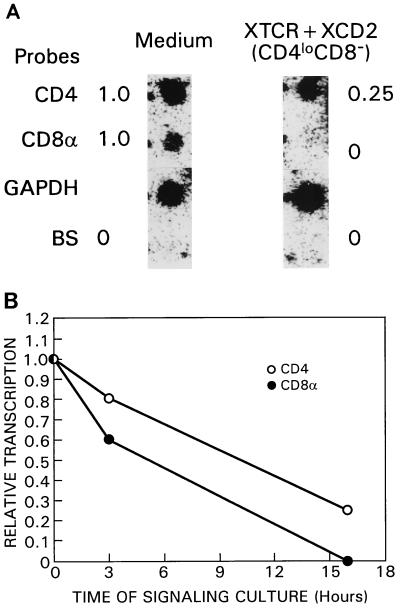

To assess the molecular events occurring in signaled DP thymocytes, DP thymocytes were isolated and stimulated by plate-bound anti-TCR and anti-CD2 MAbs (5). To assess the effect of such signals on RNAs encoding CD4 and CD8 coreceptors, we quantitated coreceptor RNAs by Northern blot analysis (Fig. 1). First, we stimulated DP thymocytes for 16 h and then physically separated them into nonresponding cells that remained CD4+CD8+ cells and responding cells that became CD4loCD8−. Nonresponding DP thymocytes fail to respond to TCR-CD2 stimulation either because they lack surface TCR or because they are unresponsive to TCR-transduced signals (5). Northern blot analysis revealed that unresponsive DP thymocytes contained both CD4 and CD8α RNAs whereas responsive, CD4loCD8− thymocytes lacked both CD4 and CD8α RNAs (Fig. 1). To determine the rapidity with which CD4 and CD8α RNAs disappeared in response to stimulation, we quantitated RNA levels at various time points after stimulation (Fig. 2). After 3 h of stimulation, both CD4 and CD8α RNA levels were reduced by 50 to 70% (Fig. 2), an impressive reduction made even more impressive by the fact that RNAs from both responding and nonresponding DP thymocytes were included in the analysis because these two subpopulations cannot be distinguished after only 3 h of signaling. Moreover, the observed quantitative reductions in CD4 and CD8α RNAs were specific for coreceptor RNAs, as the level of the RNA encoding the housekeeping enzyme GAPDH actually increased relative to the 18S RNA level, which remained constant (Fig. 2). Thus, TCR-CD2 signals induced a rapid and selective depletion of both CD4 and CD8α coreceptor RNAs in signaled DP thymocytes.

FIG. 1.

Effect of TCR-CD2 stimulation on CD4 and CD8 coreceptor RNAs in DP thymocytes. Purified DP thymocytes from IIo mice were stimulated with either medium or TCR- and CD2-specific plate-bound MAbs (XTCR + XCD2) for 16 h. Approximately 50% of DP thymocytes failed to respond (either because they did not express surface TCR complexes or because they were unable to respond to TCR-transduced signals) and remained CD4+CD8+, and approximately 50% responded by reducing surface expression of both CD4 and CD8. After stimulation, nonresponding and responding DP thymocytes were purified by electronic sorting of the cells into CD8+ and CD8− cell populations. The sorted CD8+ population consisted of CD4+CD8+ cells, whereas the CD8− cell population consisted of CD4loCD8− cells. Each cell population was assessed for CD4, CD8α, and GAPDH RNA expression by Northern blot hybridization with the indicated probes. Note that the group or lane numbers in the Northern blot analysis refer to the numbered cell populations indicated in the histograms. Lane 1, RNA from the starting cell population; lane 2, RNA from signaled thymocytes; lane 3, RNA from purified thymocytes that did not respond during signaling culture; lane 4, RNA from purified thymocytes that did respond during signaling culture. In the two-color histograms, CD4 expression is depicted on the x axis and CD8 expression is depicted on the y axis.

FIG. 2.

Rapid kinetics of coreceptor RNA loss in signaled DP thymocytes. CD4+CD8+ thymocytes were stimulated for 1 to 3 h at 37°C by anti-TCRβ and anti-CD2 [X(TCR + CD2)] plate-bound MAbs. Total RNA was analyzed by Northern blot hybridization with the probes indicated on the right. The relative amounts of RNA encoding the indicated proteins were quantitated by densitometry and are expressed in arbitrary units normalized to the 18S rRNA level. The steady-state level of 18S rRNA was unchanged by culture under these conditions.

Destabilization of preexisting coreceptor RNAs in signaled DP thymocytes.

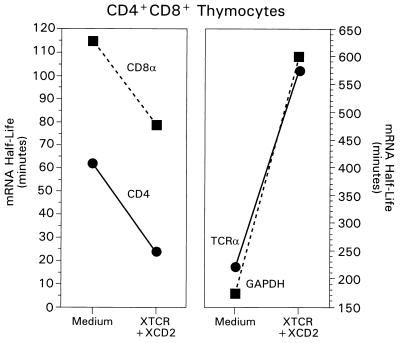

We considered that this selective loss of coreceptor RNAs in signaled DP thymocytes might have resulted from either RNA destabilization or termination of transcription, or both. However, the rapidity with which CD4 and CD8α RNA levels declined suggested that coreceptor RNAs might have been destabilized in response to stimulation. Consequently, we determined the half-lives of preexisting CD4 and CD8α RNAs with and without TCR-CD2 stimulation in the presence of actinomycin D, which prevents the synthesis of new RNA molecules (Fig. 3). We found that TCR-CD2 stimulation significantly reduced the half-lives of both CD4 and CD8α coreceptor RNAs (Fig. 3, left panel). Importantly, these reductions were specific for coreceptor RNAs, as the half-lives of RNAs encoding other molecules, such as TCRα and GAPDH, were actually increased by TCR-CD2 stimulation (Fig. 3, right panel). In fact, this experiment significantly underestimated the actual reduction in coreceptor half-lives by TCR-CD2 signals, for two reasons: (i) RNA was necessarily obtained from the total pool of DP thymocytes even though 50% of DP thymocytes are unresponsive to TCR and CD2 signals; and (ii) actinomycin D inhibits all transcription, including that of RNases which might be responsible for degrading coreceptor RNAs. We conclude that TCR and CD2 signals specifically destabilize both CD4 and CD8 coreceptor RNAs in responding DP thymocytes.

FIG. 3.

Destabilization of CD4 and CD8α RNAs in signaled DP thymocytes. Purified DP thymocytes from B6 mice were stimulated with either medium or TCR- and CD2-specific MAbs (XTCR + XCD2). To measure RNA turnover, transcription was blocked by addition of actinomycin D at the beginning of the signaling culture. Cells were cultured for up to 3 h, and then total RNA was analyzed by Northern blot hybridization with CD4, CD8α, GAPDH, and TCRα probes. The intensity of hybridization signals calculated by densitometric analysis was normalized to the 18S rRNA level (itself unchanged) and then used to calculate the percentage of specific RNA remaining. The half-life was derived from the logarithmically transformed best-fit line by linear-regression analysis. Comparable results were obtained in two independent experiments and with two different transcriptional inhibitors (actinomycin D and DRB). Left panel: squares, CD8α; circles, CD4. Right panel: squares, GAPDH, circles, TCRα.

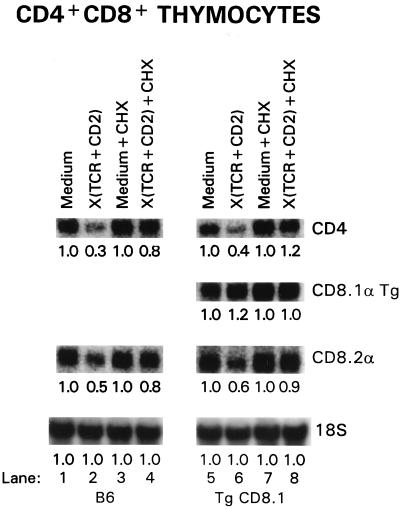

If CD4 and CD8α RNAs in DP thymocytes were degraded by proteins, such as RNases, which were synthesized in response to TCR-CD2 signals, treatment with cycloheximide (CHX), a protein synthesis inhibitor, would prevent the loss of CD4 and CD8α RNAs (22) (Fig. 4). In fact, addition of CHX to signaled DP thymocytes did prevent the loss of CD4 and CD8α RNAs (Fig. 4, lanes 1 to 4), supporting the concept that TCR-CD2 signals destabilized coreceptor RNAs by inducing the synthesis of sequence-specific proteins (such as RNases) that led to their degradation.

FIG. 4.

Protein synthesis is required for destabilization of coreceptor RNAs in signaled DP thymocytes. Purified DP thymocytes from B6 (left panel) and CD8.1α-transgenic (Tg) (right panel) mice were placed in signaling cultures for 7 h with either medium or TCR- and CD2-specific plate-bound MAbs. Where indicated, the culture also contained the protein synthesis inhibitor CHX (10 μg/ml). Total RNA from harvested cells was subjected to Northern blot analysis with the indicated probes. The number under each lane indicates the relative amount of RNA encoding the indicated protein quantitated by densitometry and expressed in arbitrary units normalized to the value for 18S rRNA. The amount of 18S rRNA was unchanged by culture under these conditions. Endogenously encoded CD8.2α mRNA and transgene-encoded CD8.1α mRNA were of different sizes and so could be distinguished from one another.

While such RNases remain poorly characterized, it is known that degradation of specific mRNA molecules often is dependent on target sequences present in the 3′ noncoding regulatory sequences of target mRNAs (20). Consequently, we assessed the destabilizing effect of TCR and CD2 signals on coreceptor RNAs that differed in noncoding regulatory sequences. We utilized B6 mice made transgenic for CD8.1α cDNA because their thymocytes contain two different populations of CD8α-specific mRNAs that can be distinguished by their different lengths: (i) CD8α mRNA that is encoded by the CD8α.1 transgene and contains CD8α structural sequences but lacks most 5′ and 3′ CD8α untranslated regulatory sequences, and (ii) CD8α mRNA that is encoded by endogenous CD8.2α genes and contains both CD8α structural and CD8α regulatory sequences. We found that stimulation significantly reduced the level of RNAs encoding endogenous CD4 and CD8.2α coreceptor molecules but not the level of RNA encoding the CD8.1α transgenic molecule (Fig. 4, lanes 5 and 6). We also confirmed that CHX blocked the TCR-signaled loss of endogenously encoded CD4 and CD8.2α RNAs even though it had no effect on RNA encoded by the CD8.1α transgene (Fig. 4, lanes 6 and 8). Importantly, the ability of CHX to prevent destabilization of coreceptor RNAs in signaled DP thymocytes was not due to CHX interfering with TCR-CD2 signal transduction, as CHX did not interfere with upregulation of CD5 RNA in the same TCR-CD2-signaled cells (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

CHX blocks destabilization of coreceptor RNAs in signaled DP thymocytes but does not interfere with TCR-CD2 signal transductiona

| DP thymocyte stimulant | Relative content of:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4 RNA

|

CD8α RNA

|

CD5 RNA

|

||||

| No CHX | CHX | No CHX | CHX | No CHX | CHX | |

| Medium | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| X(TCR + CD2) | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 4.0 | 6.1 |

DP thymocytes were stimulated for 7 h with either medium or immobilized anti-TCR and anti-CD2 MAbs [X(TCR + CD2)] in the presence or absence of CHX (10 μg/ml) and then analyzed by Northern blot hybridization with the indicated RNA probes. Samples were quantitated by densitometry, using the amount of β-actin RNA present in each sample as a loading control. The contents of RNAs encoding CD4, CD8α, and CD5 in TCR- and CD2-stimulated DP thymocytes were expressed relative to that of unstimulated DP thymocytes, which was set at 1.0 for each sample.

We conclude that (i) coreceptor RNAs are selectively destabilized in signaled DP thymocytes; (ii) destabilization of coreceptor RNAs is dependent on new protein synthesis; and (iii) destabilization of coreceptor RNAs, at least CD8α coreceptor RNA, is dependent on target sequences present in the noncoding regulatory sequences of endogenously encoded coreceptor RNAs.

Coreceptor transcription in signaled DP thymocytes.

Having demonstrated that stimulation of DP thymocytes destabilizes endogenously encoded CD4 and CD8α coreceptor transcripts, we next considered the possibility that stimulation also affects transcription of CD4 and CD8α coreceptor genes. To address this possibility, we performed nuclear run-on experiments with DP thymocytes at 0, 3, and 16 h after stimulation (Fig. 5). Note that after 16 h of stimulation, responding DP thymocytes could be purified away from nonresponding DP thymocytes by their decreased expression of surface CD4 and CD8, so that nuclear run-on experiments done after 16 h of stimulation were performed on purified populations of responding DP thymocytes that had become CD4loCD8− cells. We found that transcription of both CD4 and CD8α was reduced in response to TCR-CD2 signals (Fig. 5). Reductions in the levels of CD4 and CD8α transcription were detected after only 3 h of signaling despite the fact that we could not yet distinguish between responding and nonresponding DP thymocytes (Fig. 5B). Importantly, we did not detect CD8α transcription at all and CD4 transcription was reduced to 25% of its initial value in responding DP thymocytes after 16 h of signaling (Fig. 5). Thus, TCR-CD2 stimulation of DP thymocytes clearly reduced transcription of CD4 coreceptor genes but selectively terminated transcription of CD8α coreceptor genes.

FIG. 5.

Effect of TCR and CD2 stimulation on CD4 and CD8α gene transcription in responding DP thymocytes. (A) Purified DP thymocytes from IIo mice were stimulated for 16 h with either medium or TCR- and CD2-specific plate-bound MAbs (XTCR + XCD2). The responding CD4loCD8− population was purified from the total cell pool at the end of the signaling culture by negative selection, using three rounds of anti-CD8 panning. Nuclear run-on assays were performed on the indicated populations. The resulting labeled large-sized RNAs were purified and hybridized to nylon filters supporting immobilized denatured CD4, CD8α, and GAPDH cDNA inserts or linear Bluescript plasmid (BS) alone. Individual signals were scanned by a densitometer, with results being corrected for the background obtained when the Bluescript vector alone was used. The numbers on the right represent the fractions of the corresponding control transcription levels (presented on the left panel) and indicate the relative amounts of transcribed RNA expressed in arbitrary units normalized to the level of GAPDH RNA. Although the stability of RNA encoding the housekeeping enzyme GAPDH did change during culture, we found that the level of transcription of GAPDH RNA did not change, allowing us to normalize CD4 and CD8α transcription levels to that of GAPDH. The amount of transcribed RNA in unstimulated CD4+CD8+ thymocytes was defined as 1.0 arbitrary unit. (B) Kinetic downregulation of CD4 and CD8α transcription in responding DP thymocytes. Purified DP thymocytes from IIo mice were stimulated for 3 or 16 h with either medium alone or TCR- and CD2-specific plate-bound MAbs. At the indicated times, nuclear run-on assays were performed, and the resulting labeled large-sized RNA was purified and hybridized to nylon filters supporting immobilized denatured CD4, CD8α, and GAPDH cDNA inserts or linear Bluescript plasmid alone. The plots represent relative transcription rates of CD4 and CD8α RNAs versus time of signaling. We normalized the levels of CD4 and CD8α transcription at each time point to that of GAPDH. Note that at the 0 and 3-h time points, nuclear run-on assays were performed on total DP thymocytes, whereas at 16 h they were performed on responding CD4loCD8− cells that had been separated from nonresponding DP thymocytes by anti-CD8 panning. Because responding and nonresponding DP thymocytes cannot be distinguished by their surface phenotypes after 3 h of signaling, the 3-h time point necessarily overestimates the CD4 and CD8α transcription rates in DP thymocytes responsive to TCR-CD2 stimulation.

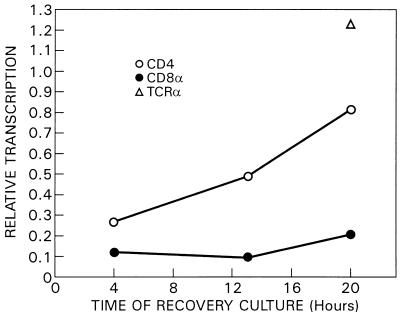

We then examined coreceptor transcription in signaled DP thymocytes on withdrawal of stimulation. Although cessation of TCR-CD2 stimulation had previously been shown to result in selective reexpression of CD4 coreceptor RNA transcripts and phenotypic conversion of signaled DP thymocytes into CD4+CD8− cells (5), the transcriptional consequences of signal termination had not been previously assessed. Consequently, we transferred stimulated DP thymocytes out of “signaling” cultures into “recovery” cultures, containing only medium, and then performed nuclear run-on assays to measure the rates of CD4 and CD8 RNA synthesis. Relative TCRα transcription, which is known to increase in signaled DP thymocytes (16), was included as a positive control (Fig. 6). We found that relative CD4 transcription increased on cessation of TCR-CD2 stimulation but that CD8α transcription did not resume (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Selective upregulation of CD4 transcription during generation of CD4+CD8− T cells in recovery culture. Purified DP thymocytes from IIo mice were stimulated for 16 h with either medium or TCR- and CD2-specific plate-bound MAbs. The CD4loCD8− cell population was obtained from the total cell pool after signaling culture with greater than 85% purity by anti-CD8 panning and collection of the nonadherent fraction. The enriched CD4loCD8− cell population was then placed in recovery culture. At the indicated time points, nuclear run-on assays were performed and the resulting labeled large-sized RNA was purified and hybridized to nylon filters supporting immobilized denatured CD4, CD8α, TCR, and GAPDH cDNA inserts or linear Bluescript plasmid alone. The plots represent relative transcription rates of CD4 and CD8α RNAs versus time of recovery. We expressed CD4 and CD8α transcription rates relative to that of GAPDH at each time point, with 1.0 representing the relative transcription rate of CD4, CD8α, or TCRα in unstimulated DP thymocytes at each time point.

We conclude that TCR-CD2 signaling in DP thymocytes terminates CD8α gene transcription but only transiently reduces CD4 gene transcription.

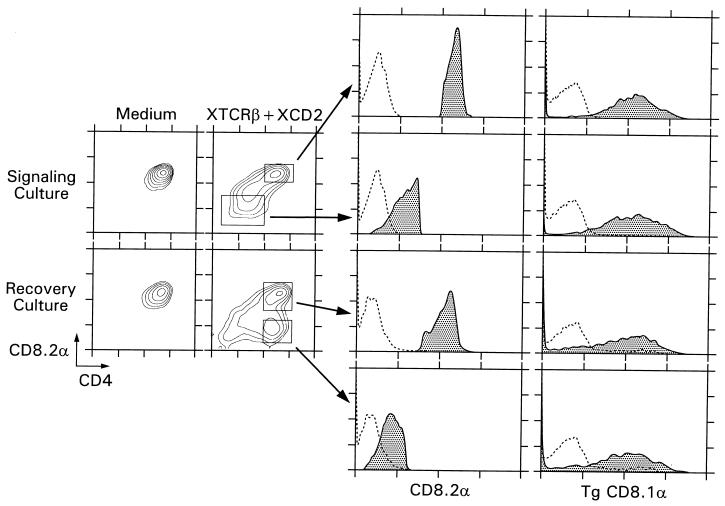

Surface expression of coreceptor proteins in signaled DP thymocytes.

Finally, we attempted to correlate the molecular events that we identified in signaled DP thymocytes with changes in surface expression of CD4 and CD8 proteins. To do so, we examined DP thymocytes from CD8α.1-transgenic mice because the transgene-encoded CD8α.1 protein differs from the endogenously encoded CD8α.2 protein by only a single amino acid that does not affect its protein function, but the RNAs encoding these proteins are differentially destabilized during signaling and their transcription is regulated by different promoter elements (an endogenous CD8α promoter versus a heterologous human CD2 promoter) (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Effect of TCR and CD2 signaling on surface expression of coreceptor proteins. Purified DP thymocytes from CD8.1α-transgenic (Tg) mice that expressed both endogenously encoded CD8.2α and transgene-encoded CD8.1α molecules were stimulated with immobilized anti-TCRβ and anti-CD2 for 16 h and then placed in recovery cultures containing only medium. Approximately 50% of DP thymocytes failed to respond to TCR and CD2 signals and remained CD4+CD8+ either because they do not express surface TCR complexes or because they are unable to respond to TCR-transduced signals. However, approximately 50% of DP thymocytes responded to TCR and CD2 signals by loss of endogenously encoded CD4 and CD8α.2 proteins from their cell surfaces to become CD4−CD8α.2−. Termination of TCR-CD2 signaling was accomplished by transfer of cells into recovery cultures that were devoid of stimulating antibodies. In recovery culture, the responding CD4−CD8α.2− thymocytes selectively reexpressed CD4 to become CD4+CD8α.2− cells. Importantly, TCR and CD2 signals modulated surface expression of endogenously encoded CD4 and CD8α.2 coreceptor molecules in DP thymocytes but did not affect expression of transgene-encoded CD8α.1 molecules (right column).

We found that TCR-CD2 signaling reduced surface expression of both endogenously encoded CD4 and CD8α.2 coreceptor proteins on responding DP thymocytes, which became CD4−CD8α.2− (Fig. 7, left panels), precisely parallel to the effect of TCR-CD2 signaling on destabilization of endogenously encoded coreceptor RNAs and diminished transcription of endogenously encoded coreceptor genes. Cessation of TCR-CD2 signaling upon transfer into recovery culture resulted in selective reexpression of CD4 (but not CD8α.2) surface protein and conversion of responding DP thymocytes into intermediate CD4+CD8α.2− thymocytes (Fig. 7, left panels). These results precisely parallel the effects of signal cessation on selective termination of endogenous CD8α.2 gene transcription. Notably, neither TCR-CD2 signaling nor its cessation had any effect on surface expression of transgene-encoded CD8α.1 proteins despite their dramatic effects on surface expression of endogenously encoded CD8α.2 proteins in the same cells (Fig. 7, right panels), precisely paralleling the absence of any effect of TCR-CD2 signals on either the stability of transgene-encoded CD8α.1 RNA or transcription from the CD8α.1 transgene. We conclude that the effects of TCR-CD2 signaling (and its cessation) on coreceptor RNA stability and coreceptor gene transcription are reflected in changes in surface expression of coreceptor proteins on signaled DP thymocytes during their conversion into intermediate CD4+CD8− thymocytes.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrated that stimulation of immature DP thymocytes by coengagement of TCR and CD2 has two important molecular consequences: (i) rapid destabilization of both CD4 and CD8 coreceptor RNAs and (ii) alterations in coreceptor gene transcription that eventually result in selective extinction of CD8α transcription. Posttranscriptional degradation of preexisting coreceptor RNAs was evident in signaled DP thymocytes within 1 to 3 h of stimulation and for CD8α was shown to be dependent on target sequences present in the noncoding regions of coreceptor RNA molecules. Coreceptor transcription was also affected by TCR-CD2 signaling in DP thymocytes, with transient reduction of CD4 gene transcription but termination of CD8α gene transcription. Thus, the present study demonstrated that posttranscriptional as well as transcriptional regulatory mechanisms can be signaled in DP thymocytes and that both regulatory mechanisms function in concert to effect the rapid conversion of signaled DP thymocytes into intermediate CD4+CD8− thymocytes.

The present study demonstrated the existence of a posttranscriptional regulatory mechanism in developing DP thymocytes. TCR-signaled destabilization of CD4 and CD8 coreceptor RNAs has previously been demonstrated to be the mechanism by which TCR signals arrest the differentiation of early CD4−CD8lo precursors into DP thymocytes (33, 34), but it has been uncertain whether posttranscriptional regulatory mechanisms also participate in later developmental steps in the thymus. In this regard, the present study revealed that TCR-CD2 signals destabilized both CD4 and CD8 coreceptor RNAs in DP thymocytes within 1 to 3 h. Indeed, the very rapidity of the elimination of preexisting coreceptor RNAs in signaled DP thymocytes is itself indicative of its physiologic relevance, as its role in signaled DP thymocytes is to alter coreceptor expression more rapidly than can be accomplished by transcriptional regulatory mechanisms alone. Notably, the rapid and transitory nature of the posttranscriptional regulatory events described in the present study makes them difficult to identify in asynchronously signaled populations of DP thymocytes in vivo.

To obtain synchronously stimulated populations of DP thymocytes for the present study, we signaled DP thymocytes in vitro with immobilized anti-TCR and anti-CD2 MAbs. We utilized both anti-TCR and anti-CD2 MAbs because we had previously found that TCR engagement alone is not sufficient to induce alterations in coreceptor expression in DP thymocytes in the absence of other thymic elements (5, 16). In contrast, coengagement of surface TCR complexes with other surface molecules, which we have called coinducer molecules, does successfully signal DP thymocytes to alter coreceptor expression, with CD2 being the most potent coinducer molecule that has been identified (5). Interestingly, CD2 and other coinducer molecules may have ligands in the thymus that normally induce their coengagement with TCR during intrathymic development, so that the requirements for signaling DP thymocytes in vitro may accurately reflect the requirements for signaling DP thymocytes in vivo. In this regard, it should be noted that the CD4+CD8− thymocytes that are generated in vitro are developmentally intermediate cells that can still further differentiate into either CD4+ or CD8+ SP T cells and so are indistinguishable from intermediate CD4+CD8− thymocytes that are the progeny of signaled DP thymocytes in vivo (Brugnera et al., submitted).

Posttranscriptional elimination of preexisting CD4 and CD8 coreceptor RNAs represents a transient mechanism for rapidly terminating synthesis of both coreceptor proteins in signaled DP thymocytes (for a review, see reference 21). However, the actual mechanism by which coreceptor RNAs are selectively degraded is not well understood. It presumably involves the synthesis of sequence-specific RNases that specifically target noncoding sequences in coreceptor RNAs in immature DP thymocytes. Such RNases may be related to the adenosine-uridine (AU) binding factors (20) that have been implicated in destabilization of various lymphokine mRNAs and whose target AU sequences are primarily present in the 3′ noncoding regions of certain mRNAs, including coreceptor RNAs.

In addition to destabilizing both CD4 and CD8 coreceptor RNAs, TCR and CD2 signals in DP thymocytes also affected coreceptor gene transcription, extinguishing CD8α gene transcription but only transiently reducing CD4 gene transcription. Importantly, CD4 transcription persisted at 25% of its initial rate and increased when signaling ceased. In contrast, CD8α transcription was terminated in signaled DP thymocytes and did not increase upon cessation of signaling, accounting for conversion of signaled DP thymocytes into intermediate CD4+CD8− cells. The control regions that regulate CD4 and CD8α gene transcription have been intensely investigated and found to be highly complex (1, 6–8, 12–14, 27, 29, 31). Of particular interest is the existence in the CD4 control region of a functional silencer element that appears to be necessary for terminating CD4 gene transcription, since no similar silencer element appears to be necessary for terminating CD8α gene transcription (12–14). Thus, it is interesting to speculate that the selective termination of CD8α gene transcription that occurs in TCR-CD2-signaled DP thymocytes may reflect the fact that termination of CD8α gene transcription, unlike termination of CD4 gene transcription, can be accomplished without specific activation of a silencer element.

In conclusion, the present study has documented that posttranscriptional and transcriptional regulatory mechanisms function coordinately in signaled DP thymocytes to effect conversion of these cells into intermediate CD4+CD8− thymocytes. We suggest that destabilization of preexisting coreceptor RNAs may be an important mechanism for rapidly, but transiently, altering coreceptor expression in immature thymocytes at various stages of development.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to B. J. Fowlkes and Ellen Robey for providing CD8α.1-transgenic mice; Remy Bosselut, Richard Hodes, and Dinah Singer for critically reading the manuscript; Larry Granger and Tony Adams for expert flow analysis and electronic cell sorting; and Yousuke Takahama for advice on nuclear run-on assays.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adlam M, Duncan D D, Ng D K, Siu G. Positive selection induces CD4 promoter and enhancer function. Int Immunol. 1997;9:877–887. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.6.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berg L J, Pullen A M, Fazekas de St. Groth B, Mathis D, Benoist C, Davis M M. Antigen/MHC-specific T cells are preferentially exported from the thymus in the presence of their MHC ligand. Cell. 1989;58:1035–1046. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90502-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhandoola A, Cibotti R, Punt J A, Granger L, Adams A J, Sharrow S O, Singer A. Positive selection as a developmental progression initiated by alpha beta TCR signals that fix TCR specificity prior to lineage commitment. Immunity. 1999;10:301–311. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen-Kiang S, Lavery D J. Pulse labeling of heterogeneous nuclear RNA in isolated nuclei. Methods Enzymol. 1989;180:82–96. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(89)80094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cibotti R, Punt J A, Dash K S, Sharrow S O, Singer A. Surface molecules that drive T cell development in vitro in the absence of thymic epithelium and in the absence of lineage-specific signals. Immunity. 1997;6:245–255. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80327-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellmeier W, Sawada S, Littman D R. The regulation of CD4 and CD8 coreceptor gene expression during T cell development. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:523–554. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellmeier W, Sunshine M J, Losos K, Hatam F, Littman D R. An enhancer that directs lineage-specific expression of CD8 in positively selected thymocytes and mature T cells. Immunity. 1997;7:537–547. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80375-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellmeier W, Sunshine M J, Losos K, Littman D R. Multiple developmental stage-specific enhancers regulate CD8 expression in developing thymocytes and in thymus-independent T cells. Immunity. 1998;9:485–496. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80632-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ernst B B, Surh C D, Sprent J. Bone marrow-derived cells fail to induce positive selection in thymus reaggregation cultures. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1235–1240. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fort P, Marty L, Piechaczyk M, el Sabrouty S, Dani C, Jeanteur P, Blanchard J M. Various rat adult tissues express only one major mRNA species from the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase multigenic family. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:1431–1442. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.5.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grusby M J, Auchincloss H, Jr, Lee R, Johnson R S, Spencer J P, Zijlstra M, Jaenisch R, Papaioannou V E, Glimcher L H. Mice lacking major histocompatibility complex class I and class II molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3913–3917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.3913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hostert A, Garefalaki A, Mavria G, Tolaini M, Roderick K, Norton T, Mee P J, Tybulewicz V L, Coles M, Kioussis D. Hierarchical interactions of control elements determine CD8α gene expression in subsets of thymocytes and peripheral T cells. Immunity. 1998;9:497–508. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80633-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hostert A, Tolaini M, Festenstein R, McNeill L, Malissen B, Williams O, Zamoyska R, Kioussis D. A CD8 genomic fragment that directs subset-specific expression of CD8 in transgenic mice. J Immunol. 1997;158:4270–4281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hostert A, Tolaini M, Roderick K, Harker N, Norton T, Kioussis D. A region in the CD8 gene locus that directs expression to the mature CD8 T cell subset in transgenic mice. Immunity. 1997;7:525–536. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80374-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jameson S C, Hogquist K A, Bevan M J. Positive selection of thymocytes. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:93–126. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.000521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kearse K P, Takahama Y, Punt J A, Sharrow S O, Singer A. Early molecular events induced by T cell receptor (TCR) signaling in immature CD4+ CD8+ thymocytes: increased synthesis of TCR-alpha protein is an early response to TCR signaling that compensates for TCR-alpha instability, improves TCR assembly, and parallels other indicators of positive selection. J Exp Med. 1995;181:193–202. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.1.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kubo R T, Born W, Kappler J W, Marrack P, Pigeon M. Characterization of a monoclonal antibody which detects all murine alpha beta T cell receptors. J Immunol. 1989;142:2736–2742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levelt C N, Eichmann K. Receptors and signals in early thymic selection. Immunity. 1995;3:667–672. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90056-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Littman D R, Gettner S N. Unusual intron in the immunoglobulin domain of the newly isolated murine CD4 (L3T4) gene. Nature. 1987;325:453–455. doi: 10.1038/325453a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malter J S. Identification of an AUUUA-specific messenger RNA binding protein. Science. 1989;246:664–666. doi: 10.1126/science.2814487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malter J S. Posttranscriptional regulation of mRNAs important in T cell function. Adv Immunol. 1998;68:1–49. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60557-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malter J S, Reed J C, Kamoun M. Induction and regulation of CD2 mRNA in human lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1988;140:3233–3236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakayama T, June C H, Munitz T I, Sheard M, McCarthy S A, Sharrow S O, Samelson L E, Singer A. Inhibition of T cell receptor expression and function in immature CD4+ CD8+ cells by CD4. Science. 1990;249:1558–1561. doi: 10.1126/science.2120773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nevins J R. Isolation and analysis of nuclear RNA. Methods Enzymol. 1987;152:234–241. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)52025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robey E, Fowlkes B J. Selective events in T cell development. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:675–705. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.003331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robey E A, Fowlkes B J, Gordon J W, Kioussis D, von Boehmer H, Ramsdell F, Axel R. Thymic selection in CD8 transgenic mice supports an instructive model for commitment to a CD4 or CD8 lineage. Cell. 1991;64:99–107. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90212-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salmon P, Boyer O, Lores P, Jami J, Klatzmann D. Characterization of an intronless CD4 minigene expressed in mature CD4 and CD8 T cells, but not expressed in immature thymocytes. J Immunol. 1996;156:1873–1879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sawada S, Scarborough J D, Killeen N, Littman D R. A lineage-specific transcriptional silencer regulates CD4 gene expression during T lymphocyte development. Cell. 1994;77:917–929. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sha W C, Nelson C A, Newberry R D, Kranz D M, Russell J H, Loh D Y. Positive and negative selection of an antigen receptor on T cells in transgenic mice. Nature. 1988;336:73–76. doi: 10.1038/336073a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siu G, Wurster A L, Duncan D D, Soliman T M, Hedrick S M. A transcriptional silencer controls the developmental expression of the CD4 gene. EMBO J. 1994;13:3570–3579. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06664.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suzuki H, Punt J A, Granger L G, Singer A. Asymmetric signaling requirements for thymocyte commitment to the CD4+ versus CD8+ T cell lineages: a new perspective on thymic commitment and selection. Immunity. 1995;2:413–425. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90149-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takahama Y, Shores E W, Singer A. Negative selection of precursor thymocytes before their differentiation into CD4+ CD8+ cells. Science. 1992;258:653–656. doi: 10.1126/science.1357752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takahama Y, Singer A. Post-transcriptional regulation of early T cell development by T cell receptor signals. Science. 1992;258:1456–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.1439838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takahama Y, Suzuki H, Katz K S, Grusby M J, Singer A. Positive selection of CD4+ T cells by TCR ligation without aggregation even in the absence of MHC. Nature. 1994;371:67–70. doi: 10.1038/371067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teh H S, Kisielow P, Scott B, Kishi H, Uematsu Y, Bluthmann H, von Boehmer H. Thymic major histocompatibility complex antigens and the alpha beta T-cell receptor determine the CD4/CD8 phenotype of T cells. Nature. 1988;335:229–233. doi: 10.1038/335229a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xia Z, Ghildyal N, Austen K F, Stevens R L. Post-transcriptional regulation of chymase expression in mast cells. A cytokine-dependent mechanism for controlling the expression of granule neutral proteases of hematopoietic cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:8747–8753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.8747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zamoyska R, Vollmer A C, Sizer K C, Liaw C W, Parnes J R. Two Lyt-2 polypeptides arise from a single gene by alternative splicing patterns of mRNA. Cell. 1985;43:153–163. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]