Abstract

Background

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have shown long‐term survival benefits in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). Nevertheless, significant concern has been raised regarding long‐term TKI‐associated vascular adverse events (VAEs). The objective of this retrospective cohort study was to investigate the incidence of VAEs in Taiwanese patients with CML treated with different TKIs (imatinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib) as well as potential risk factors.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the Taiwan Cancer Registry Database and National Health Insurance Research Database. Adult patients diagnosed with CML from 2008 to 2016 were identified and categorized into three groups according to their first‐line TKI treatment (imatinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib). Propensity score matching was performed to control for potential confounders. Cox regressions were used to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) of VAEs in different TKI groups.

Results

In total, 1,111 patients with CML were included in our study. We found that the risk of VAEs in nilotinib users was significantly higher than that in imatinib users, with an HR of 3.13 (95% confidence interval (CI), 1.30–7.51), whereas dasatinib users also showed a nonsignificant trend for developing VAEs, with an HR of 1.71 (95% CI, 0.71–4.26). In multivariable logistic regression analysis, only nilotinib usage, older age, and history of cerebrovascular diseases were identified as significant risk factors. The annual incidence rate of VAEs was highest within the first year after the initiation of TKIs.

Conclusion

These findings can support clinicians in making treatment decisions and monitoring VAEs in patients with CML in Taiwan.

Implications for Practice

This study found that patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) treated with nilotinib and dasatinib may be exposed to a higher risk of developing vascular adverse events (VAEs) compared with those treated with imatinib. Thus, this study suggests that patients with CML who are older or have a history of cerebrovascular diseases should be under close monitoring of VAEs, particularly within the first year after the initiation of tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Keywords: Chronic myeloid leukemia, Tyrosine kinase inhibitors, Vascular adverse events

Short abstract

Concerns have been raised regarding long‐term adverse events related to tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) treatment. This article reports on the incidence of TKI‐associated vascular adverse events in a cohort of Taiwanese patients with chronic myeloid leukemia.

Introduction

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a hematological malignancy derived from the fusion gene BCR‐ABL1, which is translated into a continuously activated tyrosine kinase, leading to abnormal proliferation and differentiation of hematopoietic cells [1]. In recent decades, tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have induced a paradigm shift in the treatment of CML. The first TKI, imatinib, showed significant improvement in clinical outcomes, including a better cytogenetic response and lower progression rate, compared with the traditional combination of interferon and chemotherapy in patients with CML [2]. Second‐generation TKIs (dasatinib, nilotinib, and bosutinib) further demonstrated superior molecular responses and even lower progression rates than imatinib [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]. The third‐generation TKI ponatinib, although restricted to patients with CML with more advanced disease or T315I mutation [10, 11], has also expanded the treatment options for patients with CML. Despite the different clinical profiles of these TKIs, prolonged use of TKIs is usually required for patients with CML. Concerns regarding their “long‐term” adverse events, particularly thromboembolic events associated with newer generations of TKIs, have emerged [12, 13, 14, 15, 16].

Many observational studies have suggested that newer generations of TKIs may be significantly more associated with vascular adverse events (VAEs) than imatinib is [16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28]. A retrospective cohort study conducted in Sweden indicated that the incidences of VAEs in nilotinib and dasatinib users were higher than that in imatinib users [22]. Another study including pooled patients with CML from different prospective trials also reported that newer‐generation TKIs were associated with an increased incidence of arteriothrombotic adverse events, especially ponatinib [21]. The phase II pivotal trial (EPIC trial) of ponatinib was terminated early because of the high incidence of serious VAEs in ponatinib users [10]. A meta‐analysis of 29 studies including 15,706 patients found that nilotinib and ponatinib users had a significantly higher risk of encountering major arterial events than users of other TKIs [23]. However, there have been inconsistent results in dasatinib users, with some studies suggesting an increased risk of VAEs and others suggesting the risk is not increased [8, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 29].

These inconclusive findings regarding the association between TKIs and VAEs may be due to the small sample sizes and/or the inclusion of patients with a history of VAEs in the abovementioned studies. Furthermore, studies regarding the association between TKIs and VAEs in Asian populations are scarce. It thus remains unclear whether the aforementioned findings, based primarily on clinical trials or studies conducted in Western countries, can be translated into clinical settings in Asia. By using the Taiwan Cancer Registry Database (TCRD) and National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD), we aimed to examine the association between the use of TKIs and the risk of VAEs. Potential risk factors for this association were also evaluated to provide more clinical insights.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources

We incorporated data from the TCRD and NHIRD for analysis. The TCRD is funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare in Taiwan and was established in 1979. It is considered to be an informative nationwide database for cancer surveillance, with 98.4% completeness and 91.5% morphological verification regarding a cancer diagnosis according to the data in the database in 2012. Comprehensive data, including patient demographics, cancer diagnosis with International Classification of Diseases for Oncology – 3rd edition (ICD‐O‐3) codes, treatments, and other cancer‐related prognostic factors, are recorded in TCRD [30]. Taiwan's NHIRD contains claims data from all beneficiaries enrolled in the National Health Insurance (NHI) program, which was launched in 1995 and covers more than 99% of the population (23.58 million in 2018) in Taiwan. The NHIRD comprises detailed health care information on demographics and health care utilization, including outpatient visits, hospital admissions, and prescription medications [31]. Data linkage was performed by assigning encrypted and unique identification numbers to insured individuals to generate data from the two databases for further analysis.

Ethical Statement

The identification numbers of the beneficiaries were encrypted to ensure their confidentiality. However, unique identification numbers allowed for interconnections among all database subsets of the NHI program. The protocol of this study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of National Taiwan University Hospital (registration number 201812119RIND).

Study Population

We conducted a retrospective cohort study to assess the incidence of VAEs between different TKI users. Only patients receiving imatinib, nilotinib, or dasatinib were included in this study, as bosutinib and ponatinib were not reimbursed by Taiwan's NHI during our study period.

Patients aged 20 years old and older with a diagnosis of CML (ICD‐O‐3 codes: 98753) from January 1, 2008, to December 31, 2016, were identified in the TCRD. Their treatments were retrieved from the NHIRD. We excluded patients not treated with any of the three studied TKIs (imatinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib). Patients with a prior history of VAEs, which was defined as having any diagnosis of VAEs, were also excluded. All patients with CML were categorized into three groups according to their first‐line TKI treatment (imatinib, nilotinib, or dasatinib). The cohort entry date was defined as the date of diagnosis of CML, whereas the index date was defined as the date of initiation of TKIs.

Outcomes of Interest

The outcomes of interest were VAEs, which included myocardial infarction, other ischemic heart disease, ischemic stroke, other ischemic cerebrovascular disease, arterial occlusive disease, and venous thromboembolism. The corresponding ICD‐9‐CM codes and ICD‐10‐CM codes are listed in supplemental online Table 1. Outcome occurrence was defined as a primary diagnosis of VAEs for at least one hospitalization or at least three outpatient visits. All patients with CML were followed from the index date until the date of any of the following censoring criteria: occurrence of VAEs, switch or discontinuation of TKI treatment, stem cell transplantation, death, or receipt of TKIs for 5 years since initiation.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study cohort before propensity score matching

| Variables | Nilotinib (n = 306) | Dasatinib (n = 240) | Imatinib (n = 565) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female (%) | 143 (46.7) | 90 (37.5) | 230 (40.7) | .0759 |

| Age at diagnosis, yr | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 48.3 (14.4) | 46.6 (14.6) | 49.0 (16.4) | .1411 |

| Age at initiation of TKI, yr | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 49.1 (14.4) | 47.2 (14.5) | 49.6 (16.4) | .1431 |

| Interval from CML diagnosis until first prescription of TKI, days | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 91.2 (277.6) | 57.6 (150.0) | 35.8 (130.9) | .0002 |

| Modified Charlson comorbidity index | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.6 (1.1) | 0.5 (1.0) | 0.6 (1.0) | .7356 |

| Comorbidities (%) | ||||

| Dyslipidemia | 41 (13.4) | 21 (8.8) | 62 (11.0) | .2262 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 40 (13.1) | 29 (12.1) | 76 (13.5) | .8703 |

| Hypertension | 61 (19.9) | 44 (18.3) | 136 (24.1) | .1332 |

| Congestive heart failure | 5 (1.6) | ≤3 | 12 (2.1) | .2044 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 5 (1.6) | ≤3 | 5 (0.9) | .3748 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 8 (2.6) | 4 (1.7) | 18 (3.2) | .4744 |

| Dementia | ≤3 | ≤3 | 4 (0.7) | 1.0000 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 12 (3.9) | 6 (2.5) | 32 (5.7) | .1193 |

| Rheumatic disease | ≤3 | ≤3 | 9 (1.6) | .1713 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 30 (9.8) | 29 (12.1) | 61 (10.8) | .6958 |

| Mild liver disease | 26 (8.5) | 26 (10.8) | 44 (7.8) | .3696 |

| Diabetes without chronic complication | 35 (11.4) | 28 (11.7) | 76 (13.5) | .6267 |

| Diabetes with chronic complication | 16 (5.2) | 5 (2.1) | 13 (2.3) | .0347 |

| Renal disease | 7 (2.3) | 4 (1.7) | 15 (2.7) | .6960 |

| Comedication (%) | ||||

| Aspirin | 23 (7.5) | 9 (3.8) | 30 (5.3) | .1510 |

| Circulation enhancers a | 7 (2.3) | ≤3 | 14 (2.5) | .3343 |

| Antihemorrhagics | 6 (2.0) | 4 (1.7) | 5 (0.9) | .5396 |

| Lipid‐lowering agents | 29 (9.5) | 11 (4.6) | 45 (8.0) | .9440 |

| Anti‐hypertensive agents | 52 (17.0) | 29 (12.1) | 106 (18.8) | .0681 |

| Antihyperglycemic agents | 26 (8.5) | 21 (8.8) | 64 (11.3) | .3178 |

| Hydroxyurea | 27 (8.8) | 16 (6.7) | 40 (7.1) | .5600 |

| Hormone replacement therapy | 7 (2.3) | ≤3 | 9 (1.6) | .1934 |

| Cox II inhibitors | ≤3 | ≤3 | 14 (2.5) | .0338 |

| Antipsychotics | 11 (3.6) | 7 (2.9) | 11 (1.9) | .3274 |

Circulation enhancers: pentoxifylline, nicametate citrate, dihydroergotoxine, piracetam and ginkgo biloba extract

Abbreviations: CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; Cox II, cyclooxygenase II; TKI, tyrosine.

Covariates

Baseline characteristics, including age, sex, comorbidities, and comedications, were collected 1 year prior to the index date. Comorbidities included dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and diseases included in the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) [32, 33]. The items of any malignancy and metastatic solid tumor were omitted from the CCI to avoid overadjustment. Comedications included antiplatelet agents, anticoagulants, other antithrombotic agents, circulation enhancers (pentoxifylline, nicametate citrate, dihydroergotoxine, piracetam, and ginkgo biloba extract), antihemorrhagics, lipid‐lowering agents, antihypertensive agents, antihyperglycemic agents, other traditional CML medications, and medications that may also be associated with VAEs (supplemental online Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression model for VAEs since initiation of TKIs

| Variables | OR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | <.0001 |

| TKI | ||

| Imatinib | Reference | |

| Nilotinib | 3.43 (1.53–7.69) | .0260 |

| Dasatinib | 2.39 (0.92–6.23) | .5457 |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Congestive heart failure | 3.59 (0.91–14.14) | .0673 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 3.49 (1.19–10.3) | .0233 |

| Hypertension | 2.01 (0.94–4.32) | .0734 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Statistical Analysis

The ANOVA tests were applied to compare continuous variables, and χ2 tests were applied to compare categorical variables across different TKI users. Multivariable logistic regression was conducted to investigate the association of TKI use and other risk factors with the risk of VAEs. Variables with a p value < .05 in the univariable logistic regression analysis were selected and assessed in the multivariable logistic regression analysis. Stepwise selection was used to account for potential linearity in related variables.

To reduce the selection bias inherent to retrospective cohort studies, we conducted propensity score matching to control for potential confounders [34]. Baseline characteristics, including age, sex, comorbidities, and comedications, across different TKI users were put into a logistic regression model to compute a propensity score for each patient. Each nilotinib or dasatinib user was separately matched to n (n ≤ 2) imatinib users for further analyses to create matched cohort 1 (nilotinib vs. imatinib) and matched cohort 2 (dasatinib vs. imatinib). Propensity score matching was performed by using greedy matching with a caliper of 0.25. The positivity assumption was tested by using a Kernel density plot.

Differences in baseline characteristics between nilotinib or dasatinib users and imatinib users were compared using standardized mean differences (SMDs) after propensity score matching. An SMD greater than 0.2 implied an imbalanced distribution between the two compared groups (i.e., nilotinib vs. imatinib or dasatinib vs. imatinib). The crude incidence rate and adjusted incidence rate of VAEs were calculated, with the incidence rate ratio (IRR) obtained by conducting Poisson regression. Survival analyses were conducted with the Cox proportional hazard model, and the cumulative incidence curves were compared to assess the association between TKI use and the risk of VAEs. The proportional hazard ratio assumption was tested visually by using log‐log plots.

All analyses were performed using the SAS program (version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Demographics of Patients with CML

There were 1,348 newly diagnosed patients with CML identified between 2008 and 2016, with 67 patients under 20 years of age, 30 patients treated without TKIs, and 140 patients having a history of VAEs. After excluding these patients, 1,111 adult patients with CML were included in our study cohort, with 565, 306, and 240 patients treated with first‐line imatinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib, respectively (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Patient inclusion flow chart.

The mean ages at CML diagnosis were 48.3 (SD, 14.4), 46.6 (14.6), and 49.0 (16.4) years for nilotinib, dasatinib, and imatinib users. The modified Charlson comorbidity index values were comparable across different TKI users. However, the proportions of patients who had some specific comorbid conditions were slightly different. For example, the proportion of dasatinib users (8.8%) that had dyslipidemia was lower than the proportions of nilotinib and imatinib users who had dyslipidemia (Table 1). During the follow‐up period, there were 12, 16, and 8 VAE cases in imatinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib users, with crude incidence rates of 7.9, 21.0, and 15.1 per 1,000 person‐years, respectively. In the multivariable logistic regression analysis, only nilotinib use, older age, and history of cerebrovascular diseases were significantly associated with an increased risk of VAEs (Table 2).

After propensity score matching, 286 nilotinib users were matched to 500 imatinib users (matched cohort 1), with a mean age at TKI initiation of 49 and 48 years, respectively. In addition, 236 dasatinib users were matched to 455 imatinib users (matched cohort 2), with a mean age at TKI initiation of 47 and 47 years, respectively. The baseline characteristics of the two matched cohorts were comparable, as shown in Table 3. The Kernal density plot indicated the positivity assumption was not violated (supplemental online Figs. 1, 2).

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of study cohort after propensity score matching

| Variables | Nilotinib (n = 286) | Imatinib (n = 500) | SMD | Dasatinib (n = 236) | Imatinib (n = 455) | SMD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female (%) | 131 (45.8) | 211 (42.2) | −0.07 | 87 (36.9%) | 165 (36.3%) | −0.01 |

| Age at diagnosis, yr | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 47.7 (14.5) | 47.4 (16.0) | 0.02 | 46.5 (14.6) | 46.4 (15.7) | 0 |

| Age at initiation of TKI, yr | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 48.5 (14.5) | 48.0 (16.0) | 0.03 | 47.1 (14.5) | 47.0 (15.7) | 0 |

| Interval from CML diagnosis until first prescription of TKI, days | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 92.1 (282.5) | 37.4 (138.8) | 0.25 a | 58.1 (151.3) | 31.7 (117.6) | 0.19 |

| Modified Charlson comorbidity index | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.5 (1.0) | 0.5 (1.0) | 0.02 | 0.5 (0.9) | 0.4 (0.8) | 0.08 |

| Comorbidities (%) | ||||||

| Dyslipidemia | 32 (11.2) | 50 (10.0) | 0.04 | 20 (8.5) | 38 (8.4) | 0 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 31 (10.8) | 50 (10.0) | 0.03 | 28 (11.9) | 45 (9.9) | 0.06 |

| Hypertension | 52 (18.2) | 95 (19.0) | −0.02 | 43 (18.2) | 87 (19.1) | −0.02 |

| Congestive heart failure | 4 (1.4) | 9 (1.8) | −0.03 | ≤3 | ≤3 | 0 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 4 (1.4) | 5 (1.0) | 0.04 | ≤3 | 4 (0.9) | 0 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 7 (2.4) | 7 (1.4) | 0.08 | 0 | ≤3 | −0.02 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 11 (3.8) | 24 (4.8) | −0.05 | 6 (2.5) | 12 (2.6) | −0.01 |

| Rheumatic disease | ≤3 | ≤3 | −0.04 | ≤3 | 4 (0.9) | −0.06 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 28 (9.8) | 53 (10.6) | −0.03 | 28 (11.9) | 47 (10.3) | 0.05 |

| Mild liver disease | 20 (7.0) | 35 (7.0) | 0 | 25 (10.6) | 38 (8.4) | 0.08 |

| Diabetes without chronic complication | 30 (10.5) | 50 (10.0) | 0.02 | 28 (11.9) | 45 (9.9) | 0.01 |

| Diabetes with chronic complication | 9 (3.1) | 11 (2.2) | 0.06 | 4 (1.7) | 7 (1.5) | 0.09 |

| Renal disease | 7 (2.4) | 10 (2.0) | 0.03 | 4 (1.7) | 8 (1.8) | 0.04 |

| Comedication (%) | ||||||

| Aspirin | 15 (5.2) | 25 (5.0) | 0.01 | 9 (3.8) | 18 (4.0) | −0.01 |

| Circulation enhancers | 5 (1.7) | 8 (1.6) | 0.01 | ≤3 | 4 (0.9) | 0.04 |

| Antihemorrhagics | 4 (1.4) | 5 (1.0) | 0.04 | 4 (1.7) | 5 (1.1) | 0.05 |

| Lipid‐lowering agents | 20 (7.0) | 35 (7.0) | 0 | 11 (4.7) | 24 (5.3) | −0.03 |

| Antihypertensive agents | 43 (15.0) | 76 (15.2) | 0 | 28 (11.9) | 55 (12.1) | −0.01 |

| Antihyperglycemic agents | 21 (7.3) | 38 (7.6) | −0.01 | 21 (8.9) | 35 (7.7) | 0.04 |

| Hydroxyurea | 22 (7.7) | 37 (7.4) | 0.01 | 15 (6.4) | 26 (5.7) | 0.03 |

| Hormone replacement therapy | 6 (2.1) | 9 (1.8) | 0.02 | ≤3 | ≤3 | 0 |

| Antipsychotics | 8 (2.8) | 11 (2.2) | 0.04 | 7 (3.0) | 10 (2.2) | 0.05 |

Circulation enhancers: pentoxifylline, nicametate citrate, dihydroergotoxine, piracetam, and ginkgo biloba extract.

Abbreviations: CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; SMD, standardized mean difference; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

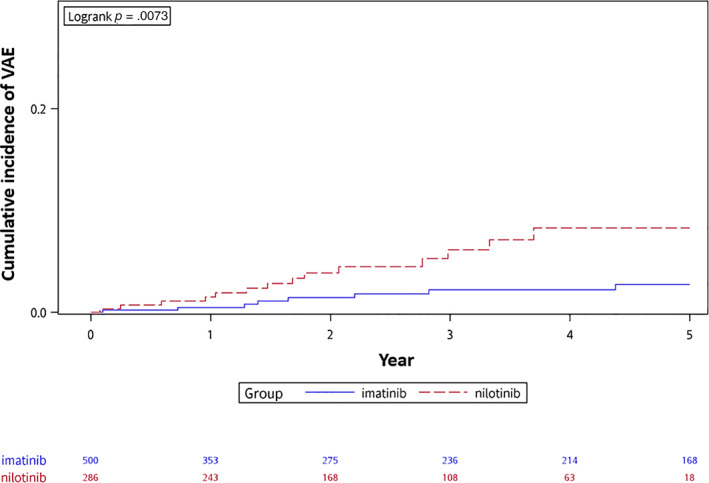

Figure 2.

The cumulative incidence curves of vascular adverse event (VAE) since initiation of imatinib or nilotinib.

The incidences of VAEs in nilotinib, dasatinib, and imatinib users are shown in Table 4. After propensity score matching, the adjusted incidence rates of VAEs were 19.2 and 5.8 per 1,000 person‐years in matched nilotinib and imatinib users, respectively, with an IRR of 3.32 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.39–7.92). The risk of VAEs in nilotinib users was significantly higher than that in imatinib users, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 3.13 (95% CI, 1.30–7.51). The cumulative incidence curves separated within the first year after the initiation of TKIs, with statistical significance (Fig. 2). On the other hand, the adjusted incidence rates of VAEs were 15.3 and 7.4 in matched dasatinib and imatinib users, respectively, with an IRR of 2.06 (95% CI, 0.79–5.34). The risk of VAEs in dasatinib users was higher than that in imatinib users, but the differences was not statistically significant, with an HR of 1.71 (95% CI, 0.71–4.26). The cumulative incidence curves are shown in Figure 3. The median time to events values were 1.9 and 1.6 years in matched imatinib and nilotinib users, respectively, and 1.5 and 0.6 years in matched imatinib and dasatinib users, respectively.

Table 4.

Association between tyrosine kinase inhibitors and occurrence of vascular adverse events

| Outcomes | Matched cohort 1 | Matched cohort 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nilotinib | Imatinib | Dasatinib | Imatinib | |

| Events | 14 | 8 | 8 | 9 |

| Total follow up, days | 728.3 | 1,382.1 | 522.54 | 1,210.1 |

| Adjusted Incidence rate, /1000 PYs | 19.2 | 5.8 | 15.3 | 7.4 |

| Incidence rate ratio (95% CI) | 3.32 (1.39–7.92) a | reference | 2.06 (0.79–5.34) | reference |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 3.13 (1.30–7.51) a | reference | 1.71 (0.71–4.26) | reference |

p value < .05

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; PYs, patient‐years.

Figure 3.

The cumulative incidence curves of vascular adverse event (VAE) since initiation of imatinib or dasatinib.

The incidence rates of VAEs in nilotinib and dasatinib users were the highest in the first year and subsequently decreased. However, no such pattern was seen in imatinib users (supplemental online Figs. 3, 4). Ischemic heart diseases were the most common VAEs, and no venous thromboembolism was observed (supplemental online Fig. 5).

Discussion

Our findings, derived from a large population‐based Taiwanese cohort, suggest that there is an increased risk of VAEs among patients with CML who use nilotinib or dasatinib. However, this association was only statistically significant among nilotinib users. The results are generally consistent with previous studies, although the incidence rate of VAEs in our study was slightly lower than that of previous studies [17, 20, 21, 22]. In the study conducted by Dahlén et al, the incidence rates of all arterial and venous events were estimated to be 16, 42, and 20 per 1,000 person‐years in imatinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib users [22], whereas the incidence rates were 8, 21, and 15 per 1,000 person‐years in our study. Nevertheless, these differences may be attributed to several factors. First, our study excluded patients with a history of VAEs to attenuate the potential misclassification of the recurrence of prior VAEs as study endpoints. However, most of the prior studies did not take this factor into consideration. Moreover, our study only included patients with CML treated with first‐line TKIs to avoid the crossover effects of prior exposure to other TKIs. Another reason for the discrepancies may be due to the different definitions of VAEs adopted by different studies. Our study adopted a strict algorithm with the requirement of a primary diagnosis of VAEs and at least three outpatient visits or one hospitalization for VAEs, which may lead to a more accurate estimation of the incidences of VAEs.

The median onset time of VAEs after the initiation of TKIs ranged from 1 to 2 years in our study. This result was quite comparable to that in most previous studies, which have showed a range of approximately 1–3 years after TKI initiation [14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 22, 24]. Some studies have even reported that the time to VAE occurrence can range from 4 to 5 years [21, 25, 29, 35]. Notably, there was a slight difference in terms of time to VAE occurrence across different TKI users in our study: 18–23 months in imatinib users, 19 months in nilotinib users, and 7 months in dasatinib users. This inconsistency may be due to the different mechanisms of action of different TKIs [36]. In terms of the annual incidence rate of VAEs, we found that it was highest in the first year, which was consistent with the study by Jain et al in 2019 [21]. This finding emphasizes the importance of close monitoring after patients with CML begin receiving their TKIs, especially within the early years.

Our study found that second‐generation TKIs, particularly nilotinib, were associated with a risk of VAEs. This finding can also be explained by the different mechanisms of different TKIs [28, 36, 37, 38]. Nilotinib may induce atherosclerosis by disturbing the metabolism of lipids and decreasing tolerance to glucose [12, 20, 36, 39, 40, 41, 42]. Additionally, nilotinib and ponatinib have been observed to impair endothelial cell and platelet function, which can increase platelet adhesion and activation [36, 43, 44, 45]. Dasatinib may damage platelet function and induce a bleeding tendency [36, 46, 47], and it may also induce dyslipidemia and potentiate the occurrence of VAEs [36, 41, 42]. This phenomenon may partly explain the inconsistent results in different studies. On the other hand, imatinib has been shown to improve the metabolism of lipids and glucose as well as enhance endothelial cell function [36, 37, 41], with a retrospective cohort study indicating a decreased incidence of VAEs in imatinib users compared with non‐TKI users [19].

Regarding potential risk factors for VAEs, we found that, in addition to nilotinib use, older age and history of cerebrovascular diseases may also increase the risk of VAEs. We also compared the baseline characteristics of those who developed VAEs and those who did not (supplemental online Table 3). We found that those who developed VAEs were older, had a higher modified CCI score, and were more likely to have comorbid conditions, such as dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, and renal disease, than those who did not develop VAEs. Those who developed VAEs were also more likely to use antiplatelet agents, anticoagulants, lipid‐lowering agents, antihypertensive agents, and antihyperglycemic agents than those who did not develop VAEs. Compared with previous studies, which indicated older age, smoking, obesity, and cardiovascular risk factors, including dyslipidemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and history of VAEs, as significant risk factors [15, 16, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 26, 38], the logistic regression in our study identified older age and history of cerebrovascular diseases in addition to nilotinib use as risk factors. Although some studies investigating prophylaxis strategies for VAEs have suggested that antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants may reduce the incidence of VAEs [17, 37, 48], no comedications used at baseline impacted the association between TKI use and the risk of VAEs in our study. Because of the limited data, there is currently no consensus on this issue. A personalized medication strategy is still required to balance the clinical benefits of preventing VAEs and the risk of bleeding.

As in many studies using claims databases as their data source, some limitations need to be addressed in our study. Although we conducted propensity score matching to attenuate potential selection bias, some variables are not routinely collected in claims data, such as family history and social history (i.e., smoking or drinking), and laboratory data were not available for our study. Second, CML itself may also contribute to the occurrence of VAEs. However, comparisons between patients with CML treated without TKIs and the general population are very difficult, as TKIs have been recognized as the gold standard treatment for CML. Including patients with CML who did not receive TKIs may introduce tremendous selection bias. Third, the follow‐up duration in dasatinib and nilotinib users was relatively shorter than that in some previous studies because of their late reimbursement in Taiwan, with the longest follow‐up duration being up to 5 years in our study. However, as previous studies indicated, most VAEs occurred within 1–3 years after the initiation of TKIs, and this issue should not greatly affect the general results of our study.

Despite these limitations, our study still has merits in addressing the association between TKIs and the risk of VAEs. Most importantly, our study is the first study with a comprehensive investigation of TKI‐associated VAEs conducted in Asia [49, 50, 51]. Although one Japanese study tried to address the same topic as our study before [49], the conclusions were of lower confidence than our conclusions because of the small sample size of the study and the inclusion of patients with exposure to other TKIs or a history of VAEs in the study. Our study used the largest sample size as well as many methodological merits, including propensity score matching, to provide valuable data on the association between TKI use and the risk of VAEs in a “real‐world” clinical setting.

Conclusion

Nilotinib may significantly increase the incidence of VAEs compared with imatinib in treating CML, whereas dasatinib also showed a trend for inducing VAEs. We suggest that patients with CML who are older or have a history of cerebrovascular diseases should be cautious when using nilotinib and dasatinib as their initial treatment. Close monitoring of VAEs, particularly within the first year after the initiation of TKIs, is warranted.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Mei‐Tsen Chen, Shih‐Tsung Huang, Chih‐Wan Lin, Bor‐Sheng Ko, Huai‐Hsuan Huang, Fei‐Yuan Hsiao

Provision of study material or patients:

Collection and/or assembly of data: Mei‐Tsen Chen

Data analysis and interpretation: Mei‐Tsen Chen, Shih‐Tsung Huang, Chih‐Wan Lin, Bor‐Sheng Ko, Wen‐Jone Chen, Huai‐Hsuan Huang, Fei‐Yuan Hsiao

Manuscript writing: Mei‐Tsen Chen, Fei‐Yuan Hsiao

Final approval of manuscript: Mei‐Tsen Chen, Shih‐Tsung Huang, Chih‐Wan Lin, Bor‐Sheng Ko, Wen‐Jone Chen, Huai‐Hsuan Huang, Fei‐Yuan Hsiao

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

Supporting information

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Appendix S1. Supporting Figures

Appendix S2. Supporting Tables

Acknowledgments

Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST 108‐2314‐B‐002‐118‐MY3). The authors thank the Health and Welfare Data Science Center, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan for making available the database used in this study.

Disclosures of potential conflicts of interest may be found at the end of this article.

No part of this article may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form or for any means without the prior permission in writing from the copyright holder. For information on purchasing reprints contact commercialreprints@wiley.com. For permission information contact permissions@wiley.com.

References

- 1. Kantarjian H, Cortes J. Chronic myeloid leukemia. In: Jameson JL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL et al., eds. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 20th ed. New York, NY: McGraw‐Hill Education, 2018;748–756. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hughes TP, Hochhaus A & Branford S et al. Reduction of BCR‐ABL transcript levels at 6, 12, and 18 months (mo) correlates with long‐term outcomes on imatinib (IM) at 72 mo: an analysis from the International Randomized Study of Interferon versus STI571 (IRIS) in patients (pts) with chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia (CML‐CP). Blood. 2008;112:334.

- 3. Saglio G, Kim DW, Issaragrisil S et al. Nilotinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2010;362:2251–2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kantarjian HM, Hochhaus A, Saglio G et al. Nilotinib versus imatinib for the treatment of patients with newly diagnosed chronic phase, Philadelphia chromosome‐positive, chronic myeloid leukaemia: 24‐month minimum follow‐up of the phase 3 randomised ENESTnd trial. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:841–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Larson R, Hochhaus A, Hughes T et al. Nilotinib vs imatinib in patients with newly diagnosed Philadelphia chromosome‐positive chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: ENESTnd 3‐year follow‐up. Leukemia 2012;26:2197–2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hughes TP, Saglio G & Larson RA et al. Long‐term outcomes in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase receiving frontline nilotinib versus imatinib: ENESTnd 10‐tear analysis. Blood. 2019;134:2924.

- 7. Hochhaus A, Saglio G, Hughes T et al. Long‐term benefits and risks of frontline nilotinib vs imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: 5‐year update of the randomized ENESTnd trial. Leukemia 2016;30:1044–1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cortes JE, Saglio G, Kantarjian HM et al. Final 5‐year study results of DASISION: The dasatinib versus imatinib study in treatment‐naïve chronic myeloid leukemia patients trial. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:2333–2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kantarjian H, Shah NP, Hochhaus A et al. Dasatinib versus imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic‐phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2010;362:2260–2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lipton JH, Chuah C, Guerci‐Bresler A et al. Ponatinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukaemia: An international, randomised, open‐label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:612–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mauro MJ, Cortes JE & Hochhaus A et al. Ponatinib efficacy and safety in patients with the T315I mutation: Long‐term follow‐up of phase 1 and phase 2 (PACE) trials. Blood. 2014;124:4552.

- 12. Aichberger KJ, Herndlhofer S, Schernthaner GH et al. Progressive peripheral arterial occlusive disease and other vascular events during nilotinib therapy in CML. Am J Hematol 2011;86:533–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Quintás‐Cardama A, Kantarjian H, Cortes J. Nilotinib‐associated vascular events. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2012;12:337–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rea D, Mirault T & Raffoux E et al. Identification of patients (pts) with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) at high risk of artery occlusive events (AOE) during treatment with the 2nd generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) nilotinib, using risk stratification for cardiovascular diseases (CVD). Blood. 2013;122:2726.

- 15. Levato L, Cantaffa R, Kropp MG et al. Progressive peripheral arterial occlusive disease and other vascular events during nilotinib therapy in chronic myeloid leukemia: A single institution study. Eur J Haematol 2013;90:531–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Le Coutre P, Rea D, Abruzzese E et al. Severe peripheral arterial disease during nilotinib therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011;103:1347–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Minson AG, Cummins K, Fox L et al. The natural history of vascular and other complications in patients treated with nilotinib for chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv 2019;3:1084–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim T, Rea D, Schwarz M et al. Peripheral artery occlusive disease in chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with nilotinib or imatinib. Leukemia 2013;27:1316–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Giles F, Mauro M, Hong F et al. Rates of peripheral arterial occlusive disease in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in the chronic phase treated with imatinib, nilotinib, or non‐tyrosine kinase therapy: A retrospective cohort analysis. Leukemia 2013;27:1310–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gora‐Tybor J, Medras E, Calbecka M et al. Real‐life comparison of severe vascular events and other non‐hematological complications in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia undergoing second‐line nilotinib or dasatinib treatment. Leuk Lymphoma 2015;56:2309–2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jain P, Kantarjian H, Boddu PC et al. Analysis of cardiovascular and arteriothrombotic adverse events in chronic‐phase CML patients after frontline TKIs. Blood Adv 2019;3:851–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dahlén T, Edgren G, Lambe M et al. Cardiovascular events associated with use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in chronic myeloid leukemia: A population‐based cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2016;165:161–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chai‐Adisaksopha C, Lam W, Hillis C. Major arterial events in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: A meta‐analysis. Leuk Lymphoma 2016;57:1300–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Valent P, Hadzijusufovic E, Schernthaner GH et al. Vascular safety issues in CML patients treated with BCR/ABL1 kinase inhibitors. Blood 2015;125:901–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Assunção PM, Lana TP, Delamain MT et al. Cardiovascular risk and cardiovascular events in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2019;19:162–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Douxfils J, Haguet H, Mullier F et al. Association between BCR‐ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitors for chronic myeloid leukemia and cardiovascular events, major molecular response, and overall survival: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:625–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Haguet H, Douxfils J, Mullier F et al. Risk of arterial and venous occlusive events in chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with new generation BCR‐ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitors: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2017;16:5–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ross DM, Arthur C, Burbury K et al. Chronic myeloid leukaemia and tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy: Assessment and management of cardiovascular risk factors. Intern Med J 2018;48(suppl 2):5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Le Coutre P, Hughes T, Mahon F et al. Low incidence of peripheral arterial disease in patients receiving dasatinib in clinical trials. Leukemia 2016;30:1593–1596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Taiwan Cancer Registry . Available at http://tcr.cph.ntu.edu.tw/main.php?Page=N1. Accessed on May 22, 2020.

- 31. National Health Insurance Administration NHI profile. Available at https://www.nhi.gov.tw/English/Content_List.aspx?n=8FC0974BBFEFA56D&topn=ED4A30E51A609E49. Accessed on May 22, 2020.

- 32. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chron Dis 1987;40:373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Quan H, Li B, Couris CM et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol 2011;173:676–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46:399–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jeon YW, Lee SE & Choi SY et al. Peripheral arterial occlusive disease (PAOD) in chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with nilotinib. Blood. 2013;122:4018.

- 36. Haguet H, Douxfils J, Chatelain C et al. BCR‐ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitors: Which mechanism(s) may explain the risk of thrombosis? TH Open 2018;2(1):e68–e88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Moslehi JJ, Deininger M. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor‐associated cardiovascular toxicity in chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:4210–4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Valent P, Hadzijusufovic E, Hoermann G et al. Risk factors and mechanisms contributing to TKI‐induced vascular events in patients with CML. Leuk Res 2017;59:47–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Breccia M, Muscaritoli M, Gentilini F et al. Impaired fasting glucose level as metabolic side effect of nilotinib in non‐diabetic chronic myeloid leukemia patients resistant to imatinib. Leuk Res 2007;31:1770–1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Delphine R, Gautier JF & Breccia M et al. Incidence of hyperglycemia by 3 years in patients (Pts) with newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase (CML‐CP) treated with nilotinib (NIL) or imatinib (IM) in ENESTnd. Blood. 2012;120:1686.

- 41. Iurlo A, Orsi E, Cattaneo D et al. Effects of first‐and second‐generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy on glucose and lipid metabolism in chronic myeloid leukemia patients: A real clinical problem? Oncotarget 2015;6:33944–33951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Franklin M, Burns L, Perez S et al. Incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidemia in patients prescribed dasatinib or nilotinib as first‐or second‐line therapy for chronic myelogenous leukemia in the US. Curr Med Res Opin 2018;34:353–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Emir H, Albrecht‐Schgoer K & Huber K et al. Nilotinib exerts direct pro‐atherogenic and anti‐angiogenic effects on vascular endothelial cells: A potential explanation for drug‐induced vasculopathy in CML. Blood. 2013;122:257.

- 44. Gover‐Proaktor A, Granot G, Shapira S et al. Ponatinib reduces viability, migration, and functionality of human endothelial cells. Leuk Lymphoma 2017;58:1455–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hadzijusufovic E, Kirchmair R & Theurl M et al. Ponatinib exerts multiple effects on vascular endothelial cells: possible mechanisms and explanations for the adverse vascular events seen in CML patients treated with ponatinib. Blood. 2016;128:1883.

- 46. Mazharian A, Ghevaert C, Zhang L et al. Dasatinib enhances megakaryocyte differentiation but inhibits platelet formation. Blood 2011;117:5198–5206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Deb S, Boknäs N, Sjöström C et al. Varying effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitors on platelet function—A need for individualized CML treatment to minimize the risk for hemostatic and thrombotic complications? Cancer Med 2020;9:313–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Caocci G, Mulas O, Abruzzese E et al. Arterial occlusive events in chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with ponatinib in the real‐life practice are predicted by the Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation (SCORE) chart. Hematol Oncol 2019;37:296–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fujioka I, Takaku T, Iriyama N et al. Features of vascular adverse events in Japanese patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: A retrospective study of the CML Cooperative Study Group database. Ann Hematol 2018;97:2081–2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kuo CY, Wang PN, Hwang WL et al. Safety and efficacy of nilotinib in routine clinical practice in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic or accelerated phase with resistance or intolerance to imatinib: Results from the NOVEL study. Ther Adv Hematol 2018;9:65–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kizaki M, Takahashi N, Iriyama N et al. Efficacy and safety of tyrosine kinase inhibitors for newly diagnosed chronic‐phase chronic myeloid leukemia over a 5‐year period: Results from the Japanese registry obtained by the New TARGET system. Int J Hematol 2019;109:426–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Appendix S1. Supporting Figures

Appendix S2. Supporting Tables