Abstract

Background

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women worldwide and the second leading cause of brain metastases (BrM). We assessed the treatment patterns and outcomes of women treated for breast cancer BrM at our institution in the modern era of stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS).

Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis of women (≥18 years of age) with metastatic breast cancer who were treated with surgery, whole brain radiotherapy (WBRT), or SRS to the brain at the Sunnybrook Odette Cancer Centre, Toronto, Canada, between 2008 and 2018. Patients with a history of other malignancies and those with an uncertain date of diagnosis of BrM were excluded. Descriptive statistics were generated and survival analyses were performed with subgroup analyses by breast cancer subtype.

Results

Among 683 eligible patients, 153 (22.4%) had triple‐negative breast cancer, 188 (27.5%) had HER2+, 246 (36.0%) had hormone receptor (HR)+/HER2−, and 61 (13.3%) had breast cancer of an unknown subtype. The majority of patients received first‐line WBRT (n = 459, 67.2%) or SRS (n = 126, 18.4%). The median brain‐specific progression‐free survival and median overall survival (OS) were 4.1 months (interquartile range [IQR] 1.0–9.6 months) and 5.1 months (IQR 2.0–11.7 months) in the overall patent population, respectively. Age >60 years, presence of neurological symptoms at BrM diagnosis, first‐line WBRT, and HER2− subtype were independently prognostic for shorter OS.

Conclusion

Despite the use of SRS, outcomes among patients with breast cancer BrM remain poor. Strategies for early detection of BrM and central nervous system–active systemic therapies warrant further investigation.

Implications for Practice

Although triple‐negative breast cancer and HER2+ breast cancer have a predilection for metastasis to the central nervous system (CNS), patients with hormone receptor–positive/HER2− breast cancer represent a high proportion of patients with breast cancer brain metastases (BrM). Hence, clinical trials should include patients with BrM and evaluate CNS‐specific activity of novel systemic therapies when feasible, irrespective of breast cancer subtype. In addition, given that symptomatic BrM are associated with shorter survival, this study suggests that screening programs for the early detection and treatment of breast cancer BrM warrant further investigation in an era of minimally toxic stereotactic radiosurgery.

Keywords: Breast neoplasms, Brain metastases, Signs and symptoms, Prognostic factors

Short abstract

Despite advances in treatment, the prognosis of patients with breast cancer brain metastasis remains poor. This article assesses treatment patterns and outcomes of such patients in the modern era of stereotactic radiosurgery.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women worldwide and the second leading cause of brain metastases (BrM) [1, 2, 3]. Despite recent treatment advances, the prognosis of patients with breast cancer BrM remains poor [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12], particularly among those with HER2− disease. Although the cause of death among patients with breast cancer BrM is challenging to ascertain, approximately 50% of patients with HER2+ BrM are thought to die of central nervous system (CNS) disease involvement [5]. The proportion of patients with triple‐negative breast cancer (TNBC) or hormone receptor (HR)+/HER2− metastatic breast cancer (MBC) who succumb to CNS disease is not well understood, but more data will emerge as results of prospective BrM screening trials become available.

Patients with breast cancer BrM typically receive a combination of local treatments consisting of surgery alone, surgery followed by postoperative radiation, or radiation alone in addition to systemic therapy. The decision regarding which treatments to offer can be challenging and often depends on clinical factors such as the number and size of BrM, presence of neurologic symptoms, patient performance status, and degree of extracranial disease control [13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21]. Unfortunately, patients with BrM perform poorly on quality of life indicators owing to neurologic symptoms secondary to their intracranial metastatic disease and treatment‐related toxicity [22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32]. As the incidence of BrM among women living with MBC continues to increase over time, likely due to improvements in early detection and systemic disease control, there is an increasing need for the implementation of evidence‐based interventions that prolong survival with minimal side effects and, in particular, preservation of neurocognitive function.

Recently, stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) has emerged as an excellent nonsurgical option with high precision and limited toxicity [19, 20]. Owing to its superior local control rates and sparing of neurocognitive function, SRS has displaced whole brain radiotherapy as the preferred radiotherapeutic option for patients with limited‐volume BrM [19, 20]. In this study, we assessed the treatment patterns and outcomes of women with breast cancer BrM at an academic cancer center in the modern era of SRS. SRS became standard of care for the treatment of patients with MBC in 2009 with the publication by Chang et al. that whole brain radiotherapy (WBRT) is associated with neurocognitive decline [33]. Uptake of SRS gradually increased, initially for selected patients with excellent performance status, controlled extracranial disease, and 1–4 BrM.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Population

This is a single‐institution retrospective study of patients (≥18 years of age) with a diagnosis of MBC treated for BrM with initial surgery, WBRT, or SRS at Sunnybrook Odette Cancer Centre, Toronto, Canada, between 2008 and 2018. This study period was selected to allow for 2‐year follow‐up among all study participants. This study was approved by our institutional ethics review board. Males, patients with a history of other primary malignancies, and those with an uncertain date of BrM diagnosis were excluded from the analysis. Data on patient demographic, pathological, and clinical outcomes were collected from the electronic patient record.

Study Outcomes

Overall survival (OS) was defined from the date of BrM diagnosis to the date of death due to any cause. Brain‐specific progression‐free survival (bsPFS) was defined from the date of BrM diagnosis until the date of radiographic disease progression in the brain specifically (patients with systemic disease progression were not censored by definition). The dates of second‐line local treatment to the brain were used as surrogates for progression in cases in which the date of progression was not documented.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient and treatment characteristics as continuous (median, range) or categorical variables (frequency). Chi‐square tests were used to compare categorical variables (i.e., treatment patterns), whereas the Kaplan‐Meier method was used to estimate OS. Univariable and multivariable analyses (UVAs and MVAs, respectively) of OS were performed with Cox proportional hazards models. From the UVA, only clinically relevant variables with a p value <.05 were included in the final MVA. All statistical analysis were conducted with R Version 3.6.1 on RStudio. A p value of <.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 683 patients with breast cancer BrM were included in the study (Fig.1). The median age at BrM diagnosis was 56 years (range 24–93), and the median time between the diagnosis of MBC and development of BrM was 8.1 months (interquartile range [IQR] 0–24.4). The distribution of breast cancer subtypes included the following frequencies: 153 (22.4%) TNBC, 188 (27.5%) HER2+, 246 (36.0%) HR+/HER2−, and 61 (13.3%) of patients had an unknown subtype. Of 646 patients for whom data regarding symptoms were available, the majority (77.5%) had neurological symptoms at their initial presentation with BrM. Asymptomatic BrM were detected as part of an evaluation for clinical trial participation or via practice patterns of select physicians, who referred patients with screen‐detected BrM to our cancer center for radiation therapy. In addition, the cumulative incidence of leptomeningeal disease (LMD) as diagnosed either clinically or via imaging was 27.3% (n = 174), including 11.1% (n = 76) who presented with LMD at the time of initial BrM diagnosis. In patients with subsequent LMD progression, the median time from BrM to LMD was 5.3 months (IQR 2.3–13.4). The most common sites of extracranial metastatic disease at the time of first BrM diagnosis were bone (67.6%), followed by lymph nodes (61.3%), lung (55.9%), and liver (53.0%). Details regarding systemic therapy received prior to first treatment with radiotherapy for BrM is included in supplemental online Table 1. A complete description of patients' clinical characteristics is presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Constitution of the study population.Abbreviations: BrM, brain metastases; CNS, central nervous system; HR, hormone receptor; MBC, metastatic breast cancer; SRS, stereotactic radiosurgery; WBRT, whole brain radiation therapy.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics | Total (n = 683) | HR+/HER2−(n = 246) | HER2+ (n = 188) | TNBC(n = 153) | Unknown (n = 96) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age at BCBM diagnosis, yr | 56 | 57 | 55 | 55 | 62 |

| Median time between MBC diagnosis and BCBM diagnosis, mo | 8.1 | 12.2 | 8.1 | 2.6 | 7.1 |

| Neurological symptoms at BCBM diagnosis, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 529 (77.5) | 192 (78.0) | 142 (75.5) | 125 (81.7) | 67 (73.6) |

| No | 117 (17.1) | 48 (19.5) | 33 (17.6) | 22 (14.4) | 12 (13.2) |

| Unknown | 37 (5.4) | 6 (2.4) | 13 (6.9) | 6 (3.9) | 12 (13.2) |

| Leptomeningeal disease, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 174 (27.3) | 72 (29.3) | 45 (23.9) | 37 (24.2) | 20 (22.0) |

| No | 485 (76.0) | 169 (68.7) | 139 (73.9) | 112 (73.2) | 60 (65.9) |

| Unknown | 24 (3.8) | 5 (2.0) | 4 (2.1) | 4 (2.6) | 11 (12.1) |

| Lymph node metastasis, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 419 (61.3) | 155 (63.0) | 117 (62.2) | 106 (69.3) | 38 (41.8) |

| No | 234 (34.3) | 88 (35.8) | 65 (34.6) | 45 (29.4) | 35 (38.5) |

| Unknown | 30 (4.4) | 3 (1.2) | 6 (3.2) | 2 (1.3) | 18 (19.8) |

| Lung metastasis, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 382 (55.9) | 141 (57.3) | 107 (56.9) | 98 (64.0) | 33 (36.3) |

| No | 271 (39.7) | 96 (39.0) | 76 (40.4) | 52 (34.0) | 45 (49.5) |

| Unknown | 30 (4.4) | 9 (3.7) | 5 (2.7) | 3 (2.0) | 13 (14.3) |

| Liver metastasis, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 362 (53.0) | 152 (61.8) | 99 (52.7) | 62 (40.5) | 46 (50.5) |

| No | 287 (42.0) | 90 (36.6) | 81 (43.1) | 83 (54.2) | 31 (34.1) |

| Unknown | 34 (5.0) | 4 (1.6) | 8 (4.3) | 8 (5.2) | 14 (15.4) |

| Bone metastasis, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 462 (67.6) | 198 (80.5) | 113 (60.1) | 91 (59.5) | 57 (62.6) |

| No | 197 (28.8) | 44 (17.9) | 71 (37.8) | 57 (37.3) | 23 (25.3) |

| Unknown | 24 (3.5) | 4 (1.6) | 4 (2.1) | 5 (3.3) | 11 (12.1) |

Abbreviations: BCBM, breast cancer brain metastasis; HR, hormone receptor; MBC, metastatic breast cancer; TNBC, triple‐negative breast cancer.

BrM Treatment Patterns and Tumor Burden

The most common first‐line treatment modality for BrM was WBRT (n = 459, 67.2%), followed by SRS (n = 126, 18.4%) and surgical resection (n = 69, 10.1%; Table 2). The proportion of patients requiring radiotherapy who were treated with SRS increased over time during the course of our study period from 0% in 2008, to 4% in 2009, to 66% in 2018 (p < .01; supplemental online Fig. 1). Patients who presented with neurological symptoms at the time of BrM diagnosis (n = 529, 77.5%) were more likely to require surgical resection (Risk Ratio (RR) = 2.74) and were less likely to be treated with SRS alone compared with those with asymptomatic disease (19.1% vs. 32.7%, RR = 0.53). Among the 117 asymptomatic patients, 107 (91.4%) received radiotherapy, whereas 5 (4.3%) received surgery as a first‐line local therapy (Table 3). In patients with LMD, 12 women received SRS treatment for BrM before the diagnosis of LMD with a median time from first SRS treatment to diagnosis of LMD of 9.0 months (IQR 4.7–13.6). Patients with symptomatic versus asymptomatic BrM had similar likelihood of presenting with a solitary lesion as opposed to multiple lesions (17.3% vs. 19.2%, p = .81).

Table 2.

Local treatments for breast cancer brain metastases by subtype

| Treatment modality | Total (n = 683) | HR+/HER2− (n = 246) | HER2+ (n = 188) | TNBC (n = 153) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First‐line local therapy, n (%) | ||||

| Radiotherapy‐based | 587 (85.9) | 218 (88.6) | 153 (81.4) | 128 (83.7) |

| SRS only | 126 (18.4) | 43 (17.5) | 45 (23.9) | 21 (13.7) |

| WBRT only | 459 (67.2) | 175 (71.1) | 106 (56.4) | 107 (69.9) |

| SRS + WBRT | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0) |

| Surgery‐based | 69 (10.1) | 17 (6.9) | 28 (14.8) | 21 (13.7) |

| Surgery alone | 33 (4.8) | 7 (2.8) | 14 (7.4) | 10 (6.5) |

| Surgery + radiotherapy | 36 (5.3) | 10 (4.1) | 14 (7.4) | 11 (7.2) |

| Treatment | 656 (96.0) | 235 (95.5) | 181 (96.3) | 149 (97.4) |

| No treatment | 27 (4) | 11 (4.5) | 7 (3.7) | 4 (2.6) |

| Retreatment for BrM progression | ||||

| Retreatment, n (%) | 182 (27.7) a | 51 (21.7) a | 83 (45.9) a | 33 (22.1) a |

| Median time from treatment for first BrM to retreatment, mo | 9 | 7.4 | 10 | 6.4 |

Percentages of patients requiring retreatment out of all patients who received first‐line local therapy.

Abbreviations: BrM, brain metastasis; HR, hormone receptor; MBC, metastatic breast cancer; SRS, stereotactic radiosurgery; TNBC, triple‐negative breast cancer; WBRT, whole brain radiation therapy.

Table 3.

Local treatments by presence versus absence of neurological symptoms at time of brain metastases diagnosis

| Neurological symptom at BrM diagnosis | Absent (n = 117) | Present (n = 529) |

|---|---|---|

| Radiotherapy‐based | 107 (91.4) | 446 (84.3) |

| SRS only | 35 (29.9) | 85 (16.1) |

| WBRT only | 72 (61.5) | 359 (67.9) |

| SRS + WBRT | 0 (0) | 2 (0.4) |

| Surgery‐based | 5 (4.3) | 62 (11.7) |

| Surgery | 3 (2.6) | 29 (5.5) |

| Surgery + radiotherapy | 2 (1.7) | 33 (6.2) |

| Treatment | 112 (95.7) | 508 (96) |

| No treatment | 5 (4.3) | 21 (4) |

Data are presented as n (%).

Abbreviations: BrM, brain metastasis; SRS, stereotactic radiosurgery; WBRT, whole brain radiation therapy.

Overall, 182 patients (26.6%) received more than one line of local treatment for BrM. Among re‐treated patients, the median time to retreatment was 7.9 months (IQR 4.2–13.7). However, patients initially treated with WBRT had lower rates of retreatment (15% vs. 45%) as well as longer median times to retreatment (9 months vs. 6.8 months) compared with patients who were initially treated with SRS. Interestingly, although the first‐line local treatment modality did not differ by breast cancer subtype (chi‐square test, p = .068), patients with HER2+ BrM were more likely to have received a second‐line local therapy (n = 83, 44.1%) compared with patients with HR+/HER2− (n = 51, 21.7%) disease and TNBC (n = 33, 22.1%).

bsPFS and Overall Survival Outcomes

The median bsPFS in our patient population was 4.1 months (IQR 1.0–9.6). On univariate analysis, only age >60 (hazard ratio, 1.29; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.03–1.61) was prognostic for shorter bsPFS. After adjusting for the effect of age, breast cancer subtype, and first local treatment modality, presence of neurological symptoms at BrM diagnosis was independently prognostic for shorter bsPFS (hazard ratio, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.02–1.78) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Factors associated with brain‐specific progression‐free survival in patients with BCBM

| Variable | Hazard Ratio a | 95% CI a | p value a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | |||

| Age at BrM diagnosis, yr | |||

| ≤60 | 1 | ||

| >60 | 1.29 | 1.03–1.61 | .028 |

| Site of metastasis at BCBM diagnosis | |||

| Lung | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.09 | 0.87–1.37 | .72 |

| Liver | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.11 | 0.89–1.38 | .43 |

| Bone | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.98 | 0.77–1.24 | .93 |

| Node | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.91 | 0.72–1.14 | .50 |

| Neurological symptom at time of BrM diagnosis | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.34 | 1.02–1.64 | .082 |

| Subtype | .09 | ||

| HR+/HER2− | 1 | ||

| HER2+ | 0.87 | 0.68–1.11 | .26 |

| Triple negative | 1.19 | 0.90–1.58 | .22 |

| First local treatment modality | .07 | ||

| WBRT | 1 | ||

| Surgery | 0.76 | 0.55–1.05 | .10 |

| SRS | 0.74 | 0.57–0.96 | .023 |

| No treatment | 0.71 | 0.36–1.38 | .31 |

| Multivariate analysis | |||

| Age at BrM diagnosis, yr | |||

| ≤60 | 1 | ||

| >60 | 1.34 | 1.07–1.68 | .011 |

| Neurological symptom at time of BrM diagnosis | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.35 | 1.02–1.78 | .037 |

| First local treatment modality | |||

| WBRT | 1 | ||

| Surgery | 0.74 | 0.53–1.02 | .070 |

| SRS | 0.73 | 0.56–0.96 | .022 |

| No treatment | 0.70 | 0.36–1.38 | .31 |

| Subtype | |||

| HR+/HER2− | 1 | ||

| HER2+ | 0.92 | 0.71–1.18 | .51 |

| Triple negative | 1.22 | 0.92–1.62 | .17 |

Patients with unknown breast cancer subtype were excluded from this analysis; 587 patients with HR+/HER2‐, HER2+ or triple negative breast cancer were included.

Abbreviations: BCBM, breast cancer brain metastasis; BrM, brain metastasis; HR, hormone receptor; MBC, metastatic breast cancer; SRS, stereotactic radiosurgery; TNBC, triple‐negative breast cancer; WBRT, whole brain radiation therapy.

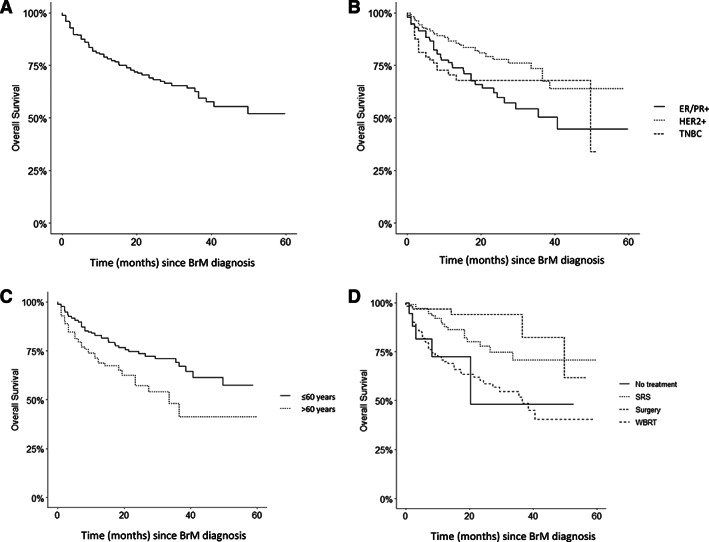

The median OS of our overall patient population was 5.1 months (IQR 2.0–11.7). In our MVA, OS was significantly associated with the type of first‐line local therapy, as well as the subtype of breast cancer. For example, compared with patients treated with WBRT in the first‐line setting, those treated with up‐front surgery (hazard ratio, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.08–0.49) or SRS (hazard ratio, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.22–0.63) lived longer (Table 5; Fig. 2). In addition, patients with HER2+ MBC had superior outcomes compared with those with TNBC and HR+/HER2− disease, respectively, in terms of median OS (12.2 vs. 3.6 vs. 4.4 months), median bsPFS (7.0 vs. 3.1 vs. 3.8 months), time to radiation retreatment (9 vs. 6.4 vs. 7.4 months), and time from retreatment to death (10.5 vs. 2.4 vs. 3.5 months). Additional prognostic factors associated with shorter OS in our MVA included age >60 years (hazard ratio, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.32–2.86; p < .001) and the presence of neurological symptoms at BrM diagnosis (hazard ratio, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.06–3.18; p < .05) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Factors associated with overall survival of patients with BCBM

| Variable | Hazard Ratio a | 95% CI a | p value a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | |||

| Age at BrM diagnosis, yr | |||

| ≤60 | 1 | ||

| >60 | 1.87 | 1.27–2.73 | .001 |

| Site of metastasis at BCBM diagnosis | |||

| Lung | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.70 | 1.10–2.50 | .029 |

| Liver | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.90 | 1.30–2.80 | .002 |

| Bone | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.20 | 0.77–1.80 | .68 |

| Node | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.30 | 0.90–2.00 | 0.21 |

| Neurological symptom at time of BrM diagnosis | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.70 | 1.00–3.00 | .047 |

| Subtype | .002 | ||

| HR+/HER2− | 1 | ||

| HER2+ | 0.55 | 0.35–0.86 | .009 |

| Triple negative | 1.19 | 0.75–1.88 | .460 |

| First local treatment modality | <.0001 | ||

| WBRT | 1 | ||

| Surgery | 0.20 | 0.08–0.49 | <.001 |

| SRS | 0.37 | 0.22–0.63 | <.001 |

| No treatment | 0.95 | 0.38–2.34 | .907 |

| Multivariate analysis | |||

| Age at BrM diagnosis, yr | |||

| ≤60 | 1 | ||

| >60 | 1.94 | 1.32–2.86 | <.001 |

| Neurological symptom at time of BrM diagnosis | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.84 | 1.06–3.18 | .030 |

| First local treatment modality | |||

| WBRT | 1 | ||

| Surgery | 0.19 | 0.08–0.48 | <.001 |

| SRS | 0.39 | 0.23–0.65 | <.001 |

| No treatment | 1.04 | 0.42–2.59 | .927 |

| Subtype | |||

| HR+/HER2− | 1 | ||

| HER2+ | 0.66 | 0.42–1.04 | .073 |

| Triple negative | 1.39 | 0.88–2.22 | .160 |

Patients with unknown breast cancer subtype were excluded from this analysis; 587 patients with HR+/HER2‐, HER2+ or triple negative breast cancer were included.

Abbreviations: BCBM, breast cancer brain metastasis; BrM, brain metastasis; HR, hormone receptor; MBC, metastatic breast cancer; SRS, stereotactic radiosurgery; TNBC, triple‐negative breast cancer; WBRT, whole brain radiation therapy.

Figure 2.

Kaplan‐Meier plots of overall survival. Kaplan‐Meier plots of overall survival (A) for all 683 patients according to (B) breast cancer subtype, (C) age at BrM diagnosis, and (D) modality of first local treatment. Abbreviations: BrM, brain metastases; ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor; SRS, stereotactic radiosurgery; TNBC, triple negative breast cancer; WBRT, whole brain radiotherapy.

Discussion

In this study, we present an analysis of BrM treatment and survival patterns in a population of patients with MBC treated with brain radiotherapy at the Sunnybrook Odette Cancer Centre between 2008 and 2018. Although WBRT was the most common first‐line local treatment for breast cancer BrM at the start of our study period, SRS predominated in 2018, which reflects changes in standard of care treatment guidelines over time. We also identify several factors that are independently prognostic for shorter OS, including age (>60 years), presence of neurological symptoms, TNBC or HR+/HER2− (as opposed to HER2+) subtype, and lack of first‐line surgical treatment.

In a large, multi‐institutional retrospective study of prognostic markers among 2,473 patients with BrM published by Sperduto et al., advanced age (≥60), lower Karnofsky performance status (≤60 as opposed to 70–80 or 90–100), presence of extracranial metastases, the number of brain metastases (≥2 vs. 1), and molecular subtype (basal or luminal A as opposed to HER2+/luminal B subtypes) were prognostic for shorter overall survival [10]. However, patients with leptomeningeal disease were not included in this study and only 7% of patients with breast cancer BrM were asymptomatic from a neurologic perspective, limiting exploration of symptoms as a potential prognosticator [10].

Unfortunately, despite recent progress in systemic and local treatments, the outcomes among patients with breast cancer BrM remain poor. In our cohort, the median bsPFS for patients with HER2+, TNBC, and HR+/HER2− BrM was as follows: 7.0 months, 3.1 months, and 3.8 months, respectively. These results are comparable with that of the large Epidemiological Strategy and Medical Economics (ESME) database, which describes the outcomes of adult patients who started treatment for MBC between January 2008 and December 2014 in one of 18 French comprehensive cancer centers [34, 35]. Of 16,701 patients in the database, approximately 25% were diagnosed with BrM, with median neurospecific PFS ranging from 3.7 months for patients with TNBC to 8.8 months for those with HER2+/HR+ disease [34]. Although brain/neurospecific PFS was not reported in the large Breast Cancer Network Registry (n = 1,712 patients diagnosed with breast cancer BrM between January 2000 and December 2016) [36], the median OS of 7.4 months is comparable to that of our cohort (5.1 months) and the ESME cohort (7.9 months) [35]. Although the median OS of 10.0 months was longer among patients in a 2010–2013 Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) population‐based study, only patients with BrM at initial diagnosis of breast cancer were assessed during a relatively narrow time period [37]. Unfortunately, a robust comparison of the populations across studies is challenging given that patterns of systemic and/or local therapies were not reported in the SEER study [37], representation of patients with leptomeningeal disease (which is high in our cohort) is not always specified, and performance status of patients is not well captured in retrospective cohorts.

In our analysis, patients with HER2+ BrM had a longer median survival compared with patients with other breast cancer subtypes. These findings are consistent with the most recent version of the Graded Prognostic Assessment, which is the gold‐standard tool for assessing prognosis among patients with breast cancer BrM [10]. Patients with HER2+ BrM also had the highest probability of receiving retreatment and had the longest survival after retreatment. This is likely related to the efficacy of targeted systemic therapies for patients with HER2+ MBC, which improve the likelihood that patients will survive to experience intracranial progression and receive local retreatment. Indeed, the increasing uptake of anti‐HER2 systemic therapies may explain why the median OS among patients with HER2+ BrM was significantly longer in the more modern U.S.‐based systHER cohort that was recruited between June 2012 and June 2016 [38] compared with that of the Breast Cancer Network Registry (median OS 11.6 months) [36] and our cohort (median OS 12.2 months).

Given that HER2‐targeted therapies, such as tucatinib [39, 40] and TDM1 [41], have demonstrated activity in the CNS, we are likely to see even better overall and brain‐specific outcomes among patients with HER2+ breast cancer BrM over time. In the HER2CLIMB study, for example, the addition of the small‐molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor tucatinib to capecitabine and trastuzumab resulted in a 46% reduction in progression or death (95% CI, 0.42–0.71; p < .001) and a 34% reduction in the risk of death (95% CI, 0.50–0.88; p = .005) [39]. The survival benefit was maintained in the subgroup of 291 patients (47.5%) with BrM receiving tucatinib‐based therapy with a hazard ratio of 0.52 (95% CI, 0.34–0.69; p < .001) [39]; furthermore, those 174 patients (28.4%) with “active” BrM that either were untreated or progressed despite local therapy demonstrated statistically significant improvements in intracranial response, CNS‐specific PFS, and OS [40]. The incorporation of novel antibody‐drug conjugates for the treatment of patients with HER2+ MBC may also improve outcomes in this patient population, although the CNS‐specific efficacy of these drugs (e.g., trastuzumab deruxtecan) requires further investigation.

The fact that patients treated with first‐line WBRT had lower radiation retreatment rates may be related to a poor performance status and subsequent inability to tolerate further radiotherapy; it is also possible that WBRT is better at controlling subclinical disease in the rest of the brain. In a large retrospective assessment of 2,553 patients with BrM (only 279 of whom had MBC), Yamamoto et al. demonstrated that patients treated with SRS for ≥5 metastases had a significantly shorter survival than those treated for 1–4 metastases (7.0 vs. 7.9 months, p = .01), although this difference was not considered to be clinically significant [42]. Furthermore, neurological death and retreatment with SRS was not significantly different among patients with ≥5 BrM as compared with those with 1–4 BrM [42]. Nevertheless, given the relatively short time period from first‐line radiation treatment to retreatment or death, patients should be selected carefully for radiation retreatment.

In our study, most patients (77.5%) presented with neurological symptoms at the time of BrM diagnosis. Importantly, the presence of neurological symptoms at the time of BrM diagnosis was associated with a threefold increase in surgical intervention, as well as shorter brain‐specific PFS and shorter OS in multivariable models as compared with asymptomatic patients. A single‐center retrospective review suggested that patients with metastatic non‐small cell lung cancer (who are typically screened for BrM) have less extensive intracranial disease and reduced need for WBRT compared with those with MBC (76% of whom were not screened for BrM) [43], but a formal comparison of asymptomatic versus symptomatic BC BrM was not conducted. A single‐center retrospective study by Koiso et al. demonstrated longer neurological deterioration‐free survival time, but not post‐SRS overall survival, in patients with asymptomatic versus symptomatic BrM; only 309 patients (10.9%) had MBC in this study [44]. In two separate single‐center retrospective reviews of patients with HER2+ breast cancer BrM, the absence of neurologic symptoms at the time of BrM diagnosis was associated with reduced need for WBRT and longer OS [45, 46]. Improved OS in patients with asymptomatic breast cancer BrM, particularly those with HER2+ disease, are supported by data from the Brain Metastases in Breast Cancer Network Germany and Japan Clinical Oncology Group registries [47, 48]. Economic analyses (based on costs of care in North Carolina as of January 2013) suggest that detection of BrM at their asymptomatic stages may even result in a financial benefit to health care systems (e.g., due to fewer neurosurgical interventions, shorter hospital admissions, less need for inpatient rehabilitation) [49]. Although such data may suggest a benefit for earlier detection of breast cancer BrM, these findings are subject to lead‐time‐bias. Results of ongoing prospective randomized (NCT03881605, NCT04030507) and nonrandomized (NCT03617341) clinical trials are awaited to better understand the potential utility of a screening program for patients with breast cancer BrM.

Previous studies have shown that patients with metastatic TNBC and HER2+ breast cancer, which represent approximately 15% and 15%–20% of breast cancer cases, respectively, have the highest risk of BrM [50, 51]. In contrast, patients with HR+/HER2− disease represent approximately 65% of the MBC population [52, 53] and have the lowest risk of BrM. In our study, the most common subtype of BC BrM was HR+/HER2− (36.0%), followed by HER2+ (27.5%) and TNBC (22.4%). Thus, despite having a lower risk of CNS spread, patients with HR+/HER2− MBC represent the greatest proportion of patients treated with radiation therapy for BrM in our institution between 2008 and 2018. Hence, further investigation of systemic therapy options for HR+/HER2− breast cancer BrM are warranted. For example, CDK4/6 inhibitors [54, 55] and PI3K inhibitors [56, 57] in combination with endocrine therapy have already shown promising CNS‐specific activity.

Systemic therapies for patients with TNBC BrM remain limited, although immunotherapy is a promising treatment strategy given that a high proportion of these BrM are programmed death‐ligand 1 positive [58, 59]. The poly(adenosine diphosphate‐ribose) inhibitor talazoparib also demonstrates promise among patients with HER2− BrM, including those with TNBC. In the EMBRCA phase II clinical trial [60], talazoparib was more effective than chemotherapy of physicians' choice among patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2‐associated metastatic HER2− breast cancer, with an improved PFS maintained in a subgroup of 63 patients (15%) with BrM. However, intracranial response of talazoparib could not be evaluated owing to exclusion of patients with active CNS disease involvement [60]. As recently reviewed by Soffietti et al., other novel systemic therapy approaches (e.g., using antiangiogenic and novel cytotoxic agents) in patients with breast cancer BrM are also under investigation [59].

In the future, data regarding the intracranial efficacy of systemic therapies may be improved with enrollment of more patients with breast cancer BrM in clinical trials [61, 62, 63] and evaluation of CNS‐specific outcomes within those trials [60]. Given the very high risk of BrM among patients with HER2+ MBC [51], strategies for secondary prevention of BrM (e.g., using temozolomide [64]) are also being investigated.

Our study had several limitations. First, we did not analyze how retreatment or survival outcomes varied by features of the BrM, such as their size or their location within the brain. Because of the increasing uptake of SRS over the time period of this study, there was also shorter follow‐up time among patients treated with SRS. In addition, given the retrospective nature of the study, we could not assess patients' quality of life or impact on neurocognition. It was also not possible to ascertain the cause of death (attributed to neurologic progression vs. systemic progression vs. others). Another limitation stems from our patient selection process. Patients in this study were all seen in consultation for possible radiotherapy or received radiation therapy at some point during their treatment course. Hence, those patients who were not referred for radiotherapy were not captured. Finally, this is a single academic center study so it may not reflect the “real world” experience.

Conclusion

Despite the use of SRS, outcomes among patients with breast cancer BrM remain poor, particularly among those who present with symptomatic disease. In the future, early detection of BrM before the development of symptoms might help improve clinical outcomes, although prospective clinical trials evaluating the possible benefits of a magnetic resonance imaging–based BrM screening program are still ongoing. Finally, despite a predilection for triple‐negative and HER2+ MBC to metastasize to the CNS, patients with HR+/HER2− disease represent a high proportion of breast cancer BrM. Hence, in addition to standardizing the use of gold‐standard radiation techniques when indicated, more CNS‐active systemic therapies must be investigated (irrespective of subtype) to improve outcomes of patients with breast cancer BrM.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Arjun Sahgal, Ellen Warner, Katarzyna J. Jerzak

Provision of study material or patients: William Tran, Katarzyna J. Jerzak

Collection and/or assembly of data: Yizhuo Kelly Gao, Markus Kuksis, Badr Id Said, Rania Chehade, Faisal Sickandar, Katarzyna J. Jerzak

Data analysis and interpretation: Yizhuo Kelly Gao, Markus Kuksis, Badr Id Said, Rania Chehade, Alex Kiss, Arjun Sahgal, Ellen Warner, Hany Soliman, Katarzyna J. Jerzak

Manuscript writing: Yizhuo Kelly Gao, Markus Kuksis, Badr Id Said, Rania Chehade, Alex Kiss, William Tran, Faisal Sickandar, Arjun Sahgal, Ellen Warner, Hany Soliman, Katarzyna J. Jerzak

Final approval of manuscript: Yizhuo Kelly Gao, Markus Kuksis, Badr Id Said, Rania Chehade, Alex Kiss, William Tran, Faisal Sickandar, Arjun Sahgal, Ellen Warner, Hany Soliman, Katarzyna J. Jerzak

Disclosures

Arjun Sahgal: AbbVie, Merck, Roche, Varian, Elekta (Gamma Knife Icon), Brainlab, VieCure (C/A), International Stereotactic Radiosurgery Society (Board Member), AO Spine Knowledge Forum Tumor (co‐chair), Elekta AB, Accuray Inc., Varian (CNS Teaching Faculty), Brainlab, Medtronic, (past educational seminars), Elekta AB (RF), Elekta, Varian, Brainlab (travel accommodations/expenses), Elekta MR Linac Research Consortium, Elekta Spine, Oligometastases and Linac Based SRS Consortia (other); Katarzyna J. Jerzak: Amgen, Apo Biologix, Eli Lilly, Esai, Exact Sciences, Knight Therapeutics, Pfizer, Merck, Novartis, Purdue Pharma, Roche, Seagen (C/A, H, SAB), Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca (RF). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

Supporting information

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Supplemental Figure 1. Proportion of patients requiring radiation therapy for breast cancer brain metastases who are treated with stereotactic radiosurgery over time

Supplemental Table 1. Systemic therapies administered to patients based on breast cancer subtype

No part of this article may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form or for any means without the prior permission in writing from the copyright holder. For information on purchasing reprints contact commercialreprints@wiley.com. For permission information contact permissions@wiley.com.

Disclosures of potential conflicts of interest may be found at the end of this article.

References

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Institutes of Health ; National Cancer Institute . Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: Female breast cancer. Available at https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html. Accessed August 21, 2019.

- 3. Lin NU, Bellon JR, Winer EP. CNS metastases in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:3608–3617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brufsky AM, Mayer M, Rugo HS et al. Central nervous system metastases in patients with HER2‐positive metastatic breast cancer: Incidence, treatment, and survival in patients from registHER. Clin Cancer Res 2011;17:4834–4843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bendell JC, Domchek SM, Burstein HJ et al. Central nervous system metastases in women who receive trastuzumab‐based therapy for metastatic breast carcinoma. Cancer 2003;97:2972–2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jung SY, Rosenzweig M, Sereika SM et al. Factors associated with mortality after breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Causes Control 2012;23:103–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Morris PG, Murphy CG, Mallam D et al. Limited overall survival in patients with brain metastases from triple negative breast cancer. Breast J 2012;18:345–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee SS, Ahn JH, Kim MK et al. Brain metastases in breast cancer: Prognostic factors and management. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2008;111:523–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ogawa K, Yoshii Y, Nishimaki T et al. Treatment and prognosis of brain metastases from breast cancer. J Neurooncol 2008;86:231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sperduto PW, Mesko S, Li J et al. Survival in patients with brain metastases: Summary report on the updated diagnosis‐specific graded prognostic assessment and definition of the eligibility quotient. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:3773–3784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sperduto PW, Kased N, Roberge D et al. Effect of tumor subtype on survival and the graded prognostic assessment for patients with breast cancer and brain metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012;82:2111–2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leone JP, Lee AV, Brufsky AM. Prognostic factors and survival of patients with brain metastasis from breast cancer who underwent craniotomy. Cancer Med 2015;4:989–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Flowers A, Levin VA. Management of brain metastases from breast carcinoma. Oncology (Williston Park) 1993;7:21–26; discussion 31‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fokstuen T, Wilking N, Rutqvist LE et al. Radiation therapy in the management of brain metastases from breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2000;62:211–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Combs SE, Schulz‐Ertner D, Thilmann C et al. Treatment of cerebral metastases from breast cancer with stereotactic radiosurgery. Strahlenther Onkol 2004;180:590–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lederman G, Wronski M, Fine M. Fractionated radiosurgery for brain metastases in 43 patients with breast carcinoma. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2001;65:145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rava P, Leonard K, Sioshansi S et al. Survival among patients with 10 or more brain metastases treated with stereotactic radiosurgery. J Neurosurg 2013;119:457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Salvetti DJ, Nagaraja TG, McNeill IT et al. Gamma Knife surgery for the treatment of 5 to 15 metastases to the brain: Clinical article. J Neurosurg 2013;118:1250–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sahgal A, Aoyama H, Kocher M et al. Phase 3 trials of stereotactic radiosurgery with or without whole‐brain radiation therapy for 1 to 4 brain metastases: Individual patient data meta‐analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2015;91:710–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sahgal A, Larson D, Knisely J. Stereotactic radiosurgery alone for brain metastases. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:249–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zagar TM, Van Swearingen AE, Kaidar‐Person O et al. Multidisciplinary management of breast cancer brain metastases. Oncology (Williston Park) 2016;30:923–933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pham A, Yondorf MZ, Parashar B et al. Neurocognitive function and quality of life in patients with newly diagnosed brain metastasis after treatment with intra‐operative cesium‐131 brachytherapy: A prospective trial. J Neurooncol 2016;127:63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yamamoto M, Serizawa T, Higuchi Y et al. A multi‐institutional prospective observational study of stereotactic radiosurgery for patients with multiple brain metastases (JLGK0901 Study Update): Irradiation‐related complications and long‐term maintenance of mini‐mental state examination scores. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2017;99:31– 40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Meyers CA, Smith JA, Bezjak A et al. Neurocognitive function and progression in patients with brain metastases treated with whole‐brain radiation and motexafin gadolinium: Results of a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Oltean D, Dicu T, Eniu D. Brain metastases secondary to breast cancer: Symptoms, prognosis and evolution. Tumori 2009;95:697–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mehta MP, Shapiro WR, Glantz MJ et al. Lead‐in phase to randomized trial of motexafin gadolinium and whole‐brain radiation for patients with brain metastases: Centralized assessment of magnetic resonance imaging, neurocognitive, and neurologic end points. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:3445–3453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. DiRisio AC, Harary M, van Westrhenen A et al. Quality of reporting and assessment of patient‐reported health‐related quality of life in patients with brain metastases: A systematic review. Neurooncol Pract 2018;5:214–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aoyama H, Tago M, Kato N et al. Neurocognitive function of patients with brain metastasis who received either whole brain radiotherapy plus stereotactic radiosurgery or radiosurgery alone. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2007;68:1388–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nakano T, Aoyama H, Saito H et al. The neurocognitive function change criteria after whole‐brain radiation therapy for brain metastasis, in reference to health‐related quality of life changes: A prospective observation study. BMC Cancer 2020;20:66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Noh T, Walbert T. Brain metastasis: Clinical manifestations, symptom management, and palliative care. Handb Clin Neurol 2018;149:75–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gerstenecker A, Nabors LB, Meneses K et al. Cognition in patients with newly diagnosed brain metastasis: Profiles and implications. J Neurooncol 2014;120:179–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wefel JS, Parsons MW, Gondi V et al. Neurocognitive aspects of brain metastasis. Handb Clin Neurol 2018;149:155–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chang EL, Wefel JS, Hess KR et al. Neurocognition in patients with brain metastases treated with radiosurgery or radiosurgery plus whole‐brain irradiation: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:1037–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pasquier D, Darlix A, Louvel G et al. Treatment and outcomes in patients with central nervous system metastases from breast cancer in the real‐life ESME MBC cohort. Eur J Cancer 2020;125:22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Darlix A, Louvel G, Fraisse J et al. Impact of breast cancer molecular subtypes on the incidence, kinetics and prognosis of central nervous system metastases in a large multicentre real‐life cohort. Br J Cancer 2019;121:991–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Witzel I, Laakmann E, Weide R et al. Treatment and outcomes of patients in the Brain Metastases in Breast Cancer Network Registry. Eur J Cancer 2018;102:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Martin AM, Cagney DN, Catalano PJ et al. Brain metastases in newly diagnosed breast cancer: A population‐based study. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:1069–1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hurvitz SA, O'Shaughnessy J, Mason G et al. Central nervous system metastasis in patients with HER2‐positive metastatic breast cancer: Patient characteristics, treatment, and survival from SystHERs. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:2433–2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Murthy RK, Loi S, Okines A et al. Tucatinib, trastuzumab, and capecitabine for HER2‐positive metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2020;382:597–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lin NU, Borges V, Anders C et al. Intracranial efficacy and survival with tucatinib plus trastuzumab and capecitabine for previously treated HER2‐positive breast cancer with brain metastases in the HER2CLIMB trial. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:2610–2619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Montemurro F, Delaloge S, Barrios CH et al. Trastuzumab emtansine (T‐DM1) in patients with HER2‐positive metastatic breast cancer and brain metastases: Exploratory final analysis of cohort 1 from KAMILLA, a single‐arm phase IIIb clinical trial. Ann Oncol 2020;31:1350–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yamamoto M, Kawabe T, Sato Y et al. A case‐matched study of stereotactic radiosurgery for patients with multiple brain metastases: Comparing treatment results for 1‐4 vs ≥ 5 tumors: Clinical article. J Neurosurg 2013;118:1258–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cagney DN, Martin AM, Catalano PJ et al. Implications of screening for brain metastases in patients with breast cancer and non–small cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:1001–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Koiso T, Yamamoto M, Kawabe T et al. A case‐matched study of stereotactic radiosurgery for patients with brain metastases: Comparing treatment results for those with versus without neurological symptoms. J Neurooncol 2016;130:581–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Morikawa A, Wang R, Patil S et al. Characteristics and prognostic factors for patients with HER2‐overexpressing breast cancer and brain metastases in the era of HER2‐targeted therapy: An argument for earlier detection. Clin Breast Cancer 2018;18:353–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Maurer C, Tulpin L, Moreau M et al. Risk factors for the development of brain metastases in patients with HER2‐positive breast cancer. ESMO Open 2018;3:e000440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Laakmann E, Witzel I, Neunhöffer T et al. Characteristics and clinical outcome of breast cancer patients with asymptomatic brain metastases. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:2787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Niikura N, Hayashi N, Masuda N et al. Treatment outcomes and prognostic factors for patients with brain metastases from breast cancer of each subtype: A multicenter retrospective analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2014;147:103–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lester SC, Taksler GB, Kuremsky JG et al. Clinical and economic outcomes of patients with brain metastases based on symptoms: An argument for routine brain screening of those treated with upfront radiosurgery. Cancer 2014;120:433–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Komorowski AS, Warner E, Mackay HJ et al. Incidence of brain metastases in nonmetastatic and metastatic breast cancer: Is there a role for screening? Clin Breast Cancer 2020;20:e54–e64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kuskis M, Gao Y, Tran W et al. The incidence of brain metastases among patients with HER2+ and triple negative metastatic breast cancer: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Neuro Oncol 2021;23:894–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Seung SJ, Traore AN, Pourmirza B et al. A population‐based analysis of breast cancer incidence and survival by subtype in Ontario women. Curr Oncol 2020;27:e191–e198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Howlader N, Cronin KA, Kurian AW et al. Differences in breast cancer survival by molecular subtypes in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2018;27:619–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Nguyen LV, Searle K, Jerzak KJ. Central nervous system‐specific efficacy of CDK4/6 inhibitors in randomized controlled trials for metastatic breast cancer. Oncotarget 2019;10:6317–6322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Anders CK, Le Rhun E, Bachelot TD et al. A phase II study of abemaciclib in patients (pts) with brain metastases (BM) secondary to HR+, HER2‐ metastatic breast cancer (MBC). J Clin Oncol 2019;37:1017–1017. [Google Scholar]

- 56. de Gooijer MC, Zhang P, Bui LCM et al. Buparlisib is a brain penetrable pan‐PI3K inhibitor. Sci Rep 2018;8:10784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Batalini F, Moulder SL, Winer EP et al. Response of brain metastases from PIK3CA‐ mutant breast cancer to Alpelisib. JCO Precis Oncol 2020;4:572–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Qazi M, Jerzak K, Nofech‐Mozes S. Biom‐07. Expression of androgen receptor and programmed death‐ligand 1 in breast‐to‐brain metastases. Neurooncol 2020;22:ii2–ii3. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Soffietti R, Ahluwalia M, Lin N et al. Management of brain metastases according to molecular subtypes. Nat Rev Neurol 2020;16:557–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Litton JK, Rugo HS, Ettl J et al. Talazoparib in patients with advanced breast cancer and a germline BRCA mutation. N Engl J Med 2018;379:753–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Corbett K, Sharma A, Pond GR et al. Central nervous system‐specific outcomes of phase 3 randomized clinical trials in patients with advanced breast cancer, lung Cancer, and melanoma. JAMA Oncol 2021;70:1062–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kim ES, Bruinooge SS, Roberts S et al. Broadening eligibility criteria to make clinical trials more representative: American Society of Clinical Oncology and Friends of Cancer Research Joint Research Statement. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:3737–3744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lee EQ, Chukwueke UN, Hervey‐Jumper SL et al. Barriers to accrual and enrollment in brain tumor trials. Neuro Oncol 2019;21:1100–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zimmer AS, Steinberg SM, Smart DD et al. Temozolomide in secondary prevention of HER2‐positive breast cancer brain metastases. Future Oncol 2020;16:899–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Supplemental Figure 1. Proportion of patients requiring radiation therapy for breast cancer brain metastases who are treated with stereotactic radiosurgery over time

Supplemental Table 1. Systemic therapies administered to patients based on breast cancer subtype