Abstract

Background:

Recent studies have shown that epigenetic alterations, especially the hypermethylated promoters of tumor suppressor genes (TSGs), contribute to prostate cancer progression and metastasis. This article proposes a novel algorithm to identify epigenetically silenced TSGs (epi-TSGs) for prostate cancer.

Methods:

Our method is based on the perception that the promoter CpG island(s) of a typical epi-TSG has a stratified methylation profile over tumor samples. In other words, we assume that the methylation profile resembles the combination of a binary distribution of a driver mutation and a continuous distribution representing measurement noise and intratumor heterogeneity.

Results:

Applying the proposed algorithm and an existing method to The Cancer Genome Atlas prostate cancer data, we identify 57 candidate epi-TSGs. Over one third of these epi-TSGs have been reported to carry potential tumor suppression functions. The negative correlations between the expression levels and methylation levels of these genes are validated on external independent datasets. We further find that the expression profiling of these genes is a robust predictive signature for Gleason scores, with the AUC statistic ranging from 0.75 to 0.79. The identified signature also shows prediction strength for tumor progression stages, biochemical recurrences, and metastasis events.

Conclusions:

We propose a novel method for pinpointing candidate epi-TSGs in prostate cancer. The expression profiling of the identified epi-TSGs demonstrates significant prediction strength for tumor progression.

Impact:

The proposed epi-TSGs identification method can be adapted to other cancer types beyond prostate cancer. The identified clinically significant epi-TSGs would shed light on the carcinogenesis of prostate adenocarcinomas.

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second leading cause of cancer mortality in American men (1). The genetic etiology of prostate cancer substantially varies among individual tumors. No single gene has been found to be mutated in the majority of prostate cancer cases (2). Recent studies suggest that epigenetic alterations contribute to prostate cancer progression and metastasis (3).

DNA methylation is a process by which methyl groups are added to a DNA molecule, classically, at cytosine residues. DNA methylation, when located in the promoter of a gene, typically acts to repress gene transcription. In humans, around 60% to 70% of genes have a CpG island in their promoter region, and most of these CpG islands remain unmethylated independently of the transcriptional activity of the gene, in both differentiated and undifferentiated cell types (4). Cancerous cells usually demonstrate abnormally hypermethylated promoter CpG islands in hundreds of genes (5). The resulting transcriptional silencing can be inherited by daughter cells following cell division (6, 7). In prostate tumors, recurrent methylation-mediated epigenetic silencing events have been observed on many cancer-related genes, such as those involved in DNA damage repair, cell-cycle control, apoptosis, and cancerous cell invasion to distant sites (3, 8).

Similar to the situation for recurrent nonsynonymous mutations in canonical tumor suppressor genes (TSGs), recurrent promoter hypermethylation events in individual genes within a tumor cohort, together with the expected negative association with gene expression levels, indicate a possibility that the gene may hold potential tumor suppression function(s). In literature, functional genes with such methylation and expression patterns in tumor samples are known as epigenetically silenced TSGs (epi-TSGs; refs. 9, 10). Recently developed high-throughput techniques, such as microarrays and next-generation sequencing, greatly facilitate the identification of epi-TSGs.

Previous genetics research shows that, although the mutant genotypes of some driver genes may have quite high frequencies or prevalence in a cancer type, no gene is genetically altered in all tumor samples of that cancer (2, 11). This indicates that the selective advantage of cancer cells is never consistently contributed by a “necessary” driver mutation or driver gene. Based on this viewpoint, it may be not too bold to assume that, for any major cancer types including prostate adenocarcinoma, the promoter methylation in an epi-TSG may contribute to carcinogenesis as a driving force but is not a “must” for tumor initiation and progression. In this regard, the primary step for the identification of an epi-TSG is to reveal the stratification of promoter methylation levels within a sample cohort rather than detecting those genes with significant difference between normal tissue and tumor samples.

Theoretically, in a pure tumor that arises from a single-cell clone, the parsimoniously defined (1–2 kb long) promoter CpG island block of an epi-TSG whose epigenetic alterations provide survival advantage to cancer cells may have a comethylation determined “methylated” or “un-methylated” haplotype (12, 13) consistently in all the contained cancerous cells. That is, underlying the methylation profile of this gene in a group of pure tumors is a Bernoulli distribution. However, in reality, a tumor sample is generally heterogeneous in that it consists of tumorous cells from multiple genetically/epigenetically differentiated ancestor cancer cells and normal stromal cells. In addition, random noise introduced in the measurement of methylation is often unavoidable. As a result, we can, at best, expect to observe a bimodal (or multimodal) population profile for the promoter methylation level of an epi-TSG.

In this study, we propose a Gaussian mixture model–based algorithm to model the promoter methylation profiles of individual genes across tumors forward to the detection of epi-TSGs and the epigenetic phenotypes of tumor samples. We apply the proposed algorithm and the adjusted version of an existing method to The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) prostate adenocarcinomas data, identifying 57 candidate epi-TSGs. We further investigate the clinical utility of these genes.

Materials and Methods

Classifier-1

Classifier-1 is a Gaussian mixture model–based algorithm, which is proposed in this study to reveal the stratification of promoter methylation levels of individual gene within a tumor cohort. The algorithm is suitable to a dataset with paired tumor and normal (tissue) specimens and is expected to be efficient when the size of tumor samples is large and/or the methylation events in the focused gene are not rare. The work flow includes the following three steps.

Step 1.

For a specific gene, the methylation metric of the ith tumor, its purity metric (ci), and the methylation metric of the paired normal tissue sample are integrated to compute a methylation index for tumor i (yi) by the following formulas:

In the analysis, we use the mean of the beta-values, which range from 0 to 1, of all CpG loci located within 3-kb-long promoter sequence of the gene to compute and . We estimate ci by the average of percent tumor cells (PTC) and percent tumor nuclei (PTN). Both PTC and PTN are retrieved from the TCGA’s clinical data. PTC denotes the ratio of tumorous cells among all the counted cells, and PTN represents the ratio of tumorous nuclei among all the counted nuclei. a and b are small positive numeric numbers (such as 0.01). These two numbers and the maximum operation are introduced to avoid the potential computational problems related to zero denominators and the logarithm of a negative number. xi can be understood as the relative methylation quantity of tumorous cells of tumor i compared with normal cells of both the paired tumor and normal specimens regarding the focused gene. When the promoter methylation levels do not differentiate between tumor cells and normal cells, the value of xi will be close to 1. When the tumor is completely pure (ci = 1), the value is approximately the observed ratio of methylation level of the tumor sample i to the methylation level of the paired normal tissue sample. Similarly, yi can be understood as the difference of log2-transformed methylation levels between tumorous and normal cells.

Step 2.

The numeric vector of the methylation indexes, , where N is the number of tumors in the analyzed dataset, is modeled by a bimodal Gaussian mixture model (Model 1). That is

The relative advantage of this model over a simple (one-mode) Gaussian model (Model 0) is evaluated by the Akaike information criterion (AIC). For a specific model and the given data, this statistic is computed as ; where k is the number of parameters to be estimated, which are 5 and 2 in Model 1 and Model 0, respectively. is the maximized value of the likelihood function of the model. Model 1 will be considered as the preferred model if its AIC is smaller than that of Model 0.

Step3.

For a gene with Model 1 as the preferred model, a binary partition of the tumor samples is generated according to the parameter estimates (, , and ). Let Pnorm represent the normal probability function. In the case of , tumor i is partitioned to the “methylated” group. Otherwise, it will be classified to the “un-methylated” group. After that, if this gene-specific partition can pass two filters, it is outputted to the container “BS-1.” The first filter is that each tumor group, i.e., “methylated” or “unmethylated,” contains at least three samples. The second filter is that the methylation level (beta-value) of all samples in the “methylated” group should be larger than a modest threshold (such as 0.15).

Classifier-2

Classifier-2 is proposed to partition tumor samples based on the promoter methylation profile of a gene, which is hypermethylated in some tumor samples, but the relative methylation measures (i.e., the methylation index defined in Step 1 of Classifier-1) compared with the paired normal tissue specimens do not favor a bimodal Gaussian mixture model. Similar to the method used in ref. 14, Classifier-2 partitions tumors by setting a minimum methylation level (beta-value) for a methylated tumor and a maximum one for a normal tissue sample. In particular, a tumor is partitioned into the methylated group if its aggregated promoter methylation level is larger than the half of the tumor purity metric and the aggregated methylation level of the paired normal sample is less than 0.1. The calculation of tumor purity metric is same as that used in Classifier-1. A quantity equal to the half of the tumor purity metric is the expected beta-value if any singe allele of a genome locus is methylated in all cancerous cells in the tumor sample. Similar to Classifier-1, a valid gene-specific partition, in which both methylated and unmethylated groups have at least three samples, will be outputted to the container “BS-2.”

Identification of epi-TSGs

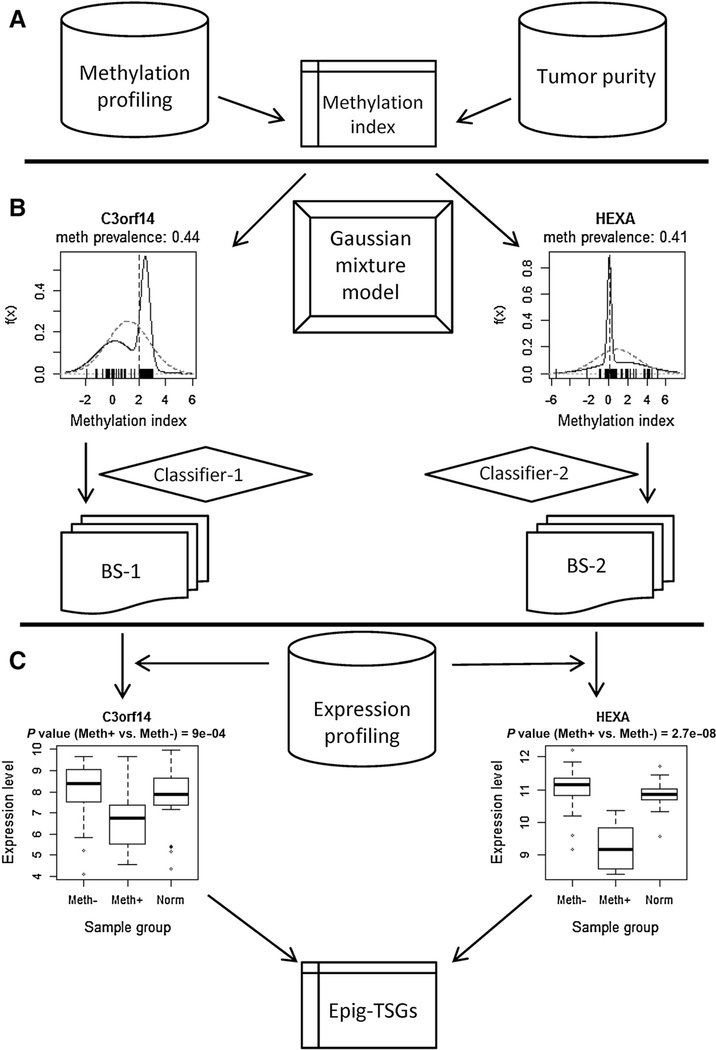

The combined results of these two classifiers include a few hundred gene-specific partitions of tumor samples. For each partition, the association between the methylation category and gene expression level is evaluated by the Mann–Whitney test. The fold change (FC) of the gene expression of the tumor samples in the methylated group compared with that of the unmethylated group is calculated as the difference of the averages of log2-transformed expression levels. Candidate epi-TSGs are selected by two criteria, i.e., FC < − 0:35 (see Supplementary Text S1 for an explanation) and Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted P value < 0.05. The procedure for identifying epi-TSGs is illustrated by Fig. 1A–C.

Figure 1.

The flow scheme for the identification of epi-TSGs. The entire procedure is divided into three phases. In phase A, the gene-specific methylation index, which integrates the promoter methylation level of individual tumor, the purity of the tumor, and the methylation level of the paired normal tissue sample, is calculated. In phase B, ts-HMGs are identified using the proposed mixture model algorithm (Classifier-1) or a naïve method (Classifer-2) similar to that used in ref. 14. In phase C, epi-TSGs are selected from ts-HMGs based on the association between gene expression levels and promoter methylation status.

Clinical utility

We use support vector machine (SVM; ref. 15), leave-one-out cross validation, Fisher exact test, and ROC method to evaluate the utility of the identified epi-TSGs in prostate cancer diagnosis and prognosis. First, based on a clinical feature of interest, such as the Gleason score (GS), the N tumors in a cohort are divided into two classes, e.g., GS < 7 (“−1” group) and GS ≥ 7 (“1” group). The labels of these tumors are then saved in a vector , where γi ∈ (−1, 1). After that, the (assumedly unknown) class of a leave-out tumor i is predicted from its gene expression (or methylation) profiling by the SVM model, which is trained on the data of the other N − 1 samples. That is,

In the equations, denotes the predicted category (1 or −1) for the ith sample; ti is the decision value, is the kernel function, and {aj} and b are the model parameters decided in the previous training process. Third, by summarizing the true label vector Y and the predicted label vector , a 2 × 2 contingency table is generated, on which the Fisher test of independence is performed. Meanwhile, the reported sensitivity and specificity are calculated according to the table. Finally, by combining the true label vector Y and an assemblage of tumor sample classifications based on the decision value vector and serially changed cutoffs, an ROC is generated, and the AUC is calculated.

Software implementation

The expectation–maximization algorithm is used to find the maximum likelihood estimates of the parameters of a Gaussian mixture model by running the norMixFit() function in the R package “nor1mix.” A SVM model is trained by the svm() function in the R package “e1071.” In the implementation, sigmoid kernel is used, and the class weights are specified as the reciprocals of the fractions of the “1” samples and “−1” samples in the training set. For other function parameters, the defaults are used.

Data

Four datasets are used in this study. The first, retrieved from the TCGA database, contains 455 primary prostate adenocarcinomas and 50 normal prostate tissue samples (paired with 50 tumor specimens) with complete DNA methylation and gene expression information. The second, from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) GSE83917 and GSE84042, contains 73 localized primary tumors with complete methylation and expression information (16). The third, from the GEO GSE21032, contains 131 primary tumors with complete gene expression information (17). The last, from GEO GSE55599, contains 10 benign hyperplasia samples and 22 carcinomas with complete methylation and expression information (18).

The DNA methylation profiling of these data was measured using the Illumina Human Methylation450 (HM450) BeadChip. The HM450 array contains 485,777 probes, including 482,421 CpG sites, 3,091 non-CpG (CpH) sites, and 65 SNPs in human genome. We use the beta-values in the downloaded data as the methylation level of a genome site. Our analysis focuses on approximately 99,700 genome sites, which are located on the CpG islands within the promoters (the 1.5-kb-long sequences flanking the transcription starting sites) of all ref-Seq genes and have beta-values in at least half of all the TCGA samples. The gene expression levels of the tumor samples in the four cancer cohorts were measured using different platforms and were preprocessed using standard methods by the authors of those data. We download the normalized datasets from the TCGA and GEO databases. Before the analysis, further preprocessing is performed (see Supplementary Text S2 for a brief description). The clinical data of the TCGA, GSE83917, and GSE21032 samples are used to evaluate the clinical utility of the identified epi-TSGs. The pursued clinical features, including pathologic GS, pathologic T category, and biochemical recurrence after treatment, of these cohorts are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample statistics of the datasets used to evaluate the diagnostic and prognostic utility of the identified epi-TSGs

| TCGA | GSE21032 | GSE83917 | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Pathologic GS | |||

| NA | 148 | 1 | 0 |

| G6 | 58 | 41 | 16 |

| G7 | 166 | 74 | 57 |

| G8 | 43 | 8 | 0 |

| G9 | 39 | 7 | 0 |

| G10 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Pathologic T category | |||

| NA | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| T2a | 14 | 9 | 4 |

| T2b | 12 | 47 | 1 |

| T2c | 154 | 29 | 35 |

| T3a | 149 | 28 | 24 |

| T3b | 114 | 10 | 9 |

| T3c | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| T4 | 9 | 6 | 0 |

| BCR | |||

| NA | 66 | 0 | 0 |

| NO | 340 | 104 | 55 |

| YES | 49 | 27 | 18 |

NOTE: The pathologic GSs in the TCGA data are the reviewed GSs retrieved from ref. 14.

Results

Tumor-specific hypermethylated genes

Using the information of 50 TCGA prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD) samples and the paired normal prostate tissue samples, we identify 711 tumor-specific hypermethylated genes (ts-HMG) whose promoter CpG sites are “methylated” in some of tumors in the cohort. Among these ts-HMGs, 309 genes (Set-A, 43%) are determined by Classifier-1. Another 402 genes (Set-B, 57%), which do not meet the criteria of Classifier-1, are determined by Classifier-2. The methylation profile of the genes in Set-1 but not in Set-2 demonstrates a clear stratification pattern across tumors. That is, the distribution of the derived methylation indexes could be better fit by a bimodal Gaussian (normal) mixture model than a simple normal model. It is worthy to note that the efficacies of Classifier-1 in the statistical identification of ts-HMGs and methylation stratification somewhat subject to the size of the analyzed (or available) tumor and normal sample pairs. If the size is sufficiently large, such as 500 rather than 50, more ts-HMGs could be identified and Set-A would account for a higher percentage.

epi-TSGs

Fifty-seven candidate epi-TSGs (Fig. 2A; Supplementary Table S1), amounting to 8% of the ts-HMGs, are selected using the procedure and criteria described in the Materials and Methods section. Three genes, including SEPT9, ELAVL2, and TNFAIP8, are “epigenetically activated.” That is, unlike epi-TSGs, these outliers have higher expression levels in the methylated tumors compared with the unmethylated ones.

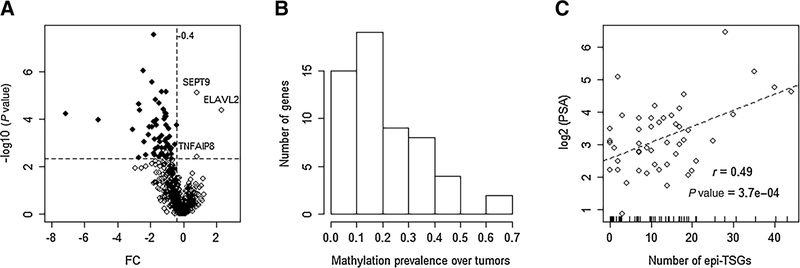

Figure 2.

Characterization of epi-TSGs. A, The volcano plot for the differences of expression levels of ts-HMGs between the gene-specific “methylated” groups and “unmethylated” groups. The P values (y axis)are estimated by the Mann–Whitney test. Each point represents a gene, and the identified epi-TSGs are denoted by the solid circles. Among the genes located within the top-left plot defined by the horizontal vertical dotted lines, two are excluded from the epi-TSG list because their expression levels (FPKMs) are low (< 2.0) in most tumor samples. B, The distribution of methylation prevalence (Prev) of epi-TSGs. Prev is calculated as the ratio of the methylated tumors to the entire studied tumors. The first column bar indicates that 15 genes have a Prev between 0 and 0.1. C, The distribution of methylation burdens of tumors and the correlation with the blood PSA levels. Each tumor is represented as an open circle in the scatter plot. The methylation burden is correspondingly indicated by a short bar over the x axis.

For each one of the epi-TSG, we calculate its “methylation prevalence” as the ratio of the methylated tumors to the total considered tumors (N= 50). As shown in Fig. 2B, the distribution of the methylation prevalence is skewed with a long tail on the right side. The epi-TSGs with the ratios between 0.1 and 0.2 are most populous. Only two genes are methylated in over 50% of tumors. For each tumor, we calculate its “methylation burden” as the number of methylated epi-TSGs. The values distribute evenly in the interval of 0 to 22. A few tumors have over 25 methylated epi-TSGs (Fig. 2C). A strong positive correlation (r = 0:49; P = 3:7 × 10−4) is demonstrated between the methylation burdens and the logarithm-translated PSA levels of patients. We further notice that the association is dominated by the 5 influential observations where the tumors have top methylation burden. If these observations are filtered out in the calculation as “outliers,” the correlation will become insignificant (r = 0:17; P = 0:78). We also find that a few tumors which are TMPRSS2-ERG fusion-negative but host a relatively heavier point mutation burden on canonical driver genes tend to have a larger methylation burden (Supplementary Fig. S1).

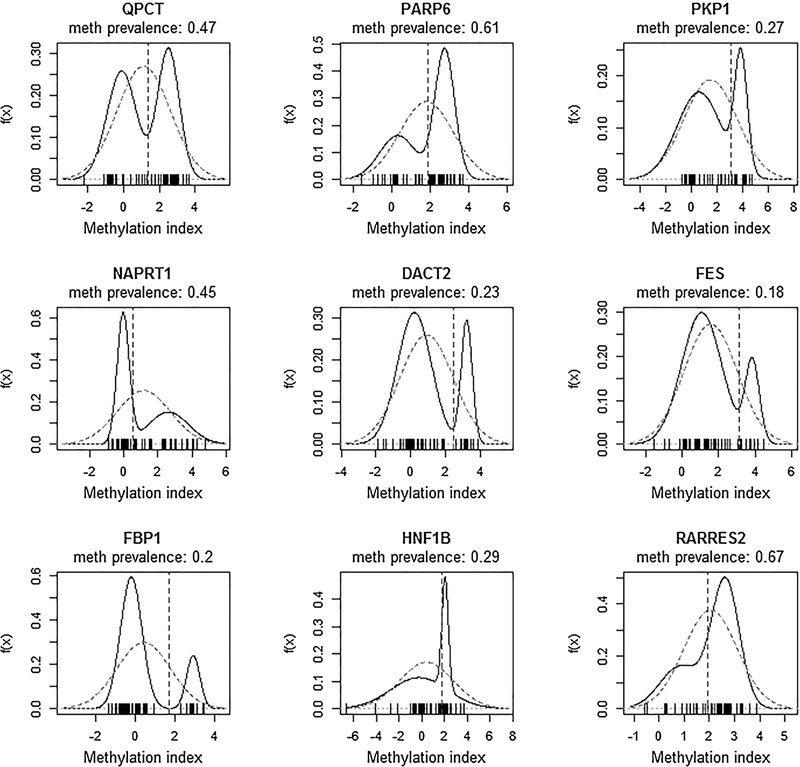

Of the 57 epi-TSGs, 22 genes pinpointed by Classifier-1 have clear across-tumors stratification patterns (Fig. 1 and Fig. 3), as demonstrated by the two-mode distribution of the derived methylation indexes. The genomic information and statistical analysis results of these genes are summarized in Table 2. Evidence of potential tumor suppression functions has been reported in 10 (including DACT2, C3orf14, and eight others) of these 22 genes and in 11 of the 35 epi-TSGs identified by Classifier-2. The relevant biological processes include Wnt/beta-catenin pathway, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, AMPK signaling, and others (Supplementary Table S1). For such a gene, the well-defined “unmethylated” or “methylated” status is somewhat analogous to its genetic type “wild” or “mutant,” respectively. The recurrent methylation events in tumors suggest that, similar to the germline and somatic mutations in well-known tumor driver genes (such as TP53), the epigenetic alterations may contribute to the selection advantage of cancer cells over normal cells in tumor formation and progression. On the other hand, because the promoter methylation status is not the only determinant for gene transcription, the expression levels of an epi-TSG in tumors can be similar to or different from those in the normal tissue samples, as demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. S2.

Figure 3.

The bimodal distributions of the methylation indexes in 9 of the epi-TSGs identified by Classifier-1. All of these genes and C3orf14 (whose methylation index distribution is presented in Fig. 1) have been reported to carry potential tumor suppression functions. In each plot, the dotted vertical line denotes the cutoff for separating the methylated tumors from unmethylated ones. A zero value of methylation index indicates that the methylation level of tumorous cells is equal to the level of normal cells. When the index is 2, the methylation level of tumorous cells is 4 times (22) of that of normal cells. For the 9 genes depicted in this figure, the dotted lines are exclusively on the right of the zero point, indicating that the methylation level of a methylated tumor is always higher than the level of its paired normal specimen (an intuitive criterion which is exerted by Classifier-2). Such a pattern is also observed for the other 13 epi-TSGs identified by Classifier-1.

Table 2.

The overview of candidate epi-TSGs with the promoter methylation levels stratified across tumors

| Gene (Chr.) | Prev | FC | P value | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| OSBPL9 (chr1) | 0.36 | −0.39 | 1.73E–04 | |

| PKP1 (chr1) | 0.32 | −1.69 | 1.5E–05 | (19) |

| QPCT (chr2) | 0.46 | −1.05 | 1.8E–04 | (20) |

| B3GALNT1 (chr3) | 0.18 | −1.66 | 1.8E–04 | |

| C3orf14 (chr3) | 0.44 | −1.44 | 9.0E–04 | (21) |

| SLC25A20 (chr3) | 0.2 | −1.07 | 7.0E–06 | |

| SUSD5 (chr3) | 0.38 | −1.03 | 6.8E–04 | |

| CDKL2 (chr4) | 0.44 | −1.18 | 9.9E–05 | |

| CXCL1 (chr4) | 0.28 | −2.41 | 9.0E–04 | |

| DACT2 (chr6) | 0.24 | −3.06 | 2.7E–04 | (22, 23) |

| DLX6 (chr7) | 0.26 | −2.13 | 4.5E–04 | |

| RARRES2 (chr7) | 0.64 | −0.75 | 4.4E–03 | (24) |

| ADAM32 (chr8) | 0.3 | −1.79 | 1.2E–04 | |

| NAPRT1 (chr8) | 0.48 | −1.34 | 7.1E–06 | (25) |

| FBP1 (chr9) | 0.2 | −1.42 | 6.0E–04 | (26) |

| C13orf38 (chr13) | 0.26 | −2.66 | 4.0E–05 | |

| ACOT4 (chr14) | 0.2 | −1.07 | 7.3E–05 | |

| FES (chr15) | 0.2 | −1.10 | 7.3E–05 | (27, 28) |

| PARP6 (chr15) | 0.62 | −0.83 | 5.3E–04 | (29) |

| HNF1B (chr17) | 0.34 | −1.68 | 1.8E–03 | (30, 31) |

| ZNF135 (chr19) | 0.2 | −1.09 | 5.5E–05 | |

| SLC7A4 (chr22) | 0.32 | −2.08 | 2.2E–04 | |

Abbreviations: FC, the fold change of the gene expression of the tumor samples in the methylated group compared with the unmethylated group. FC is calculated as the difference of the averages of log2-transformed expression levels; P value, the significance level for the differential gene expression between the methylated tumor group and unmethylated one. It is estimated by the Mann–Whitney test; Prev, methylation prevalence, calculated as the ratio of the methylated tumors among all the considered tumors; Ref, references that report the tumor suppression function of the corresponding gene.

Robustness of epigenetic gene silencing

In the procedure for identifying epi-TSGs, we determine epigenetic gene silencing via comparing the methylated and unmethylated groups. However, this approach has a limitation in that the preceding tumor classification (or partition) step needs the methylation information of paired normal tissue samples, which could be unavailable in most cases. An alternative method, which is less direct but less data-demanding, is to evaluate the correlation (r) between the gene expression levels and DNA methylation levels of tumor samples. That is, a negative r value is considered as the indicator of epigenetic gene silencing. Here, we first test the significance of the correlations in the 57 epi-TSGs using the expression and DNA methylation data of 405 TCGA tumors which are not used for epi-TSGs identification. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S3A, all the 57 Pearson correlation coefficients are negative, and 56 of them have the P values less than 0.01, corresponding to a validation rate of 0.98 (56=57). We also perform the same analysis on two external datasets (GSE83917 and GSE55599) in which 49 and 55 of the 57 epi-TSGs have the complete information. On a less demanding significance criterion (P < 0.05), the validation rates of epigenetic gene silencing are 0.61 and 0.45, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S3B and S3C). In the results of GSE55599, there are two outliers (BCAT2 and C10orf13), show a significant positive rather than negative correlation between expression and methylation metrics. A main reason for the decreased validation rates on the two external data is the small cohort size. Due to the general low methylation prevalence (<0.2) and the potential variability over cohorts (sourced from random sampling), for some of the epi-TSGs, the methylated tumors within a small sample set may be rare. In such a case, the methylation–expression association tends to be weak and elusive to detect. This perception is supported by the result of an additional analysis (Supplementary Fig. S4). That is, for normal tissues, only 10 of the 57 epi-TSGs have a significant negative correlation between the methylation and expression metrics.

Clinical utility of the identified epi-TSGs

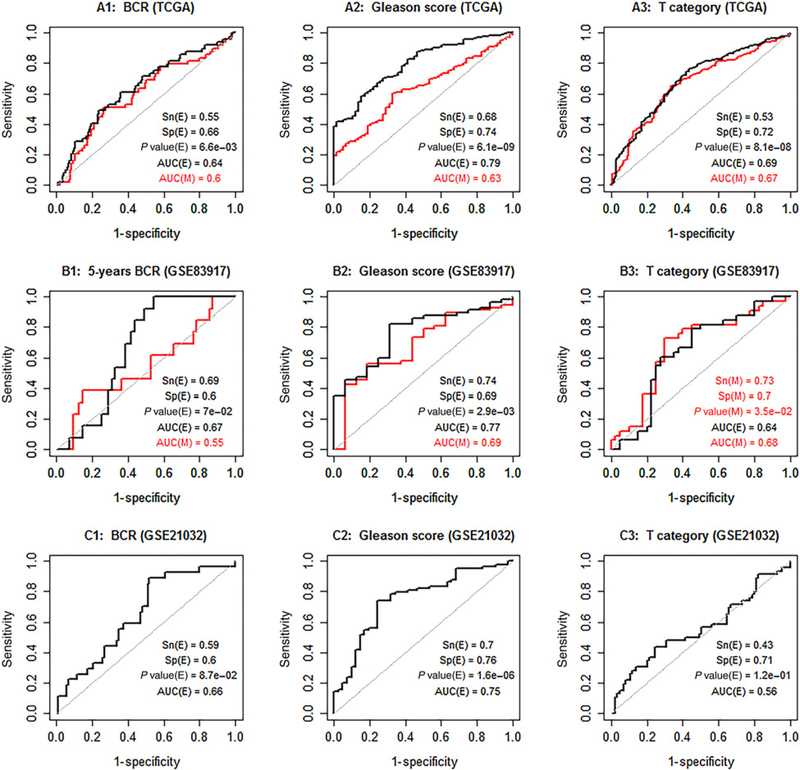

The above-mentioned correlation between the methylation burden and PSA level as well as the robustness of epigenetic gene silencing inspires us to further investigate the clinical utility of the identified epi-TSGs. We perform this study using an integrative method of machine learning and Fisher test. The expression profiling (E-profiling) and the methylation profiling (M-profiling) of the 57 genes are considered as potential predictive signatures for biochemical (PSA) recurrence (BCR) of patients, GSs of tumors, and cancer stages (T Category). The results (Fig. 4) show that (i) in TCGA data, E-profiling and M-profiling have similar prediction strength for all the focused clinical features; (2) E-profiling is a robust predictor for GS with almost identical AUC statistics (ranging from 0.75 to 0.79) achieved on the TCGA dataset and two external datasets; and (3) the prediction strength of E-profiling is generally stronger than that of M-profiling. “Metastasis after treatment” is a more important clinical feature to predict. However, only in GSE21032 (among the three datasets), the events of metastasis are recorded for patients. From this limited data, we find that E-profiling is a highly promising marker for metastasis (AUC = 0.9; Supplementary Fig. S5).

Figure 4.

The assessment of the clinical utility of the expression profiling (E-profiling) and promoter methylation profiling (M-profiling) of the identified 57 epi-TSGs. The two classes, i.e., “negative” and “positive”, for BCR are “NO” and “YES.” Similarly, the two classes for GSs are “<7” and “>= 7,” and the two classes for T-category are “T2” and “T3 & T4.” In each plot, the red and black ROC curves represent the results of M-profiling and E-profiling, respectively. The sensitivity (Sn), specificity (Sp), P value, and AUC for the E-profiling are denoted by Sn(E), Sp(E), P value(E), and AUC(E), respectively. Similarly, these statistics for the M-profiling are denoted by Sn(M), Sp(M),P value(M), and AUC(M), respectively. In each plot, we report the better values of Sp, Sn, and P value obtained from either the E-profiling or M-profiling signature. The printed Sn, Sp, and P value are calculated from a contingency table which depends on the signs (+ or −) of the decision values of tumor cases. The ROC curve is generated from a set of contingency tables that are based on the signs of the differences between the decision values of tumor cases and serially changed cutoffs. The dataset GSE83917 that contains DNA methylation quantities is complemented by GSE84042 that contains gene expression quantities.

Comparison with the TCGA group’s relevant analysis

The TCGA group identified 164 epigenetically silenced genes in prostate cancer (14), among which 22 are overlapped with our epi-TSGs. In Supplementary Text S3, we present a comparative review of their results and methods. By doing so, we further demonstrate that our work represents a unique study in identifying epi-TSGs for prostate cancer (Supplementary Figs. S6A–S6C, S7A–S7C, and S8).

Discussion

Hypermethylation of CpG islands located in the promoter regions of genes is an important mechanism of gene inactivation. For a classical TSG, such as MLH1 that plays roles in DNA repair, the promoter methylation events after a genetic mutation on one allele can serve as the “second hit” for the loss of its normal functions (32). More popularly, methylation aberrations arise on less typical TSGs in which a genetically damaged allele is not necessarily recessive and somatic mutations are rarely observed. Such genes account for the majority of the epi-TSGs identified in our study and documented in literature (14). In most publications, candidate epi-TSGs were selected (based on the association between the expression level and methylation level) from the genes for which the tumors had significantly higher methylation levels in the promoter CpG sites than normal tissue samples (33–35). The candidate epi-TSGs identified in such a way actually hold the distinguishing attribute of cancer diagnosis markers rather than tumor drivers. In our study, candidate epi-TSGs are selected from the genes whose methylation profile is stratified across tumors, i.e., both “methylated” and “un-methylated” promoter statuses are not rare among the tumors of a patient cohort. This makes the identified epi-TSGs resemble the canonical cancer driver genes whose most etiological property is the recurrence of mutated genotypes in tumors of different patients (36–38). The major unique point of our method is that the stratified methylation profile of an epi-TSG is identified and characterized via modeling the distribution of the gene-specific methylation indexes which integrates the methylation level of individual tumor, the purity of the tumor, and the methylation level of the paired normal tissue sample. A remaining challenge is how to augment the existing data so that the information of the tumors for which the DNA methylation of paired normal tissues is not available can be also included in the proposed mixture model, leading to an improved accuracy and efficacies in identifying epi-TSGs.

We identify 57 candidate epi-TSGs in this study. They could be considered as a portion of the potential methylation-mediated TSGs in prostate cancer. This is because, in our analysis, only the genes with a methylation frequency over 5% are considered. Here, we emphasize the methodologic implication of identifying the 10 epi-TSGs highlighted in Table 2. That is, a couple of facts about these genes imply that, in detecting and pursuing driver methylation events, the statistical methods which have been developed for studying the discretely distributed driver mutations could be barrowed. The facts include (i) the tumor suppression functions of the 10 genes have been demonstrated or suggested in previous publications (Table 2; refs. 19–31) and (ii) the methylation statuses in a tumor are well determined by the clearly stratified across-tumor methylation profiles. We also note that these genes can be divided into three categories, representing an uncompleted but a typical taxonomy of potential epi-TSGs. The first category includes PKP1, QPCT, DACT2, RARRES2, NAPRT1, FBP1, PARP6, and HNF1B, which have been well annotated regarding their products and functions. The second includes FES, which is first identified as an oncogene but is also a potential TSG as implicated by the recent genetic evidence. The third includes C3orf14, which has been widely reported as a promising TSG but remains to be substantially annotated. An elusive problem arises from the observed positive correlation between the methylation burdens and patient PSA levels. The observation implies that some of the 57 epi-TSGs may play roles in suppressing the invasion of tumor cells to distant sites, which can lead to the extra release of PSA to blood. However, to our knowledge, direct evidences for this argument are still missing in literature.

The potential application of DNA methylation in the diagnosis and prognosis of prostate cancer has been widely investigated in the past decade. Most of the accumulated evidences are obtained from the studies which focus on a small set of genes, including GSTP1, APC, RUNX3, PITX2, RASSF1A, TGFB2, RARB, HOX genes, and others (39, 40). For example, promoter methylation in APC and HOXD3 was identified as a biomarker for prostate cancer progression by (41) and (42), respectively. In the past years, with large-scale epigenome-wide DNA methylation profiling data becoming available, researchers in biomedical communities have been looking for biomarker panels of multiple CpG sites or genes, which are expected to be more predictive, compared with a single-gene signature, for the interested clinical features of cancer patients. In several publications (43–45), the authors firstly scanned all the CpG sites of a high-throughput methylation platform to identify the top (such as 5%) predictive ones for the interested classification (e.g., high-lethal vs. low-lethal) of tumors or the related clinical items. Then, an integrated prediction signature was derived from the previously selected features via the multivariate analysis and/or multi-regression analysis. However, such a supervised or semisupervised method often suffers from the problem of overfitting. That is, the robustness of the established prediction signature cannot be guaranteed (Supplementary Text S4; Supplementary Fig. S9A–S9C). In our study, the epi-TSGs are identified without using the progression features of tumors. So, it is no wonder that the prediction strength of the methylation profiling and expression profiling (for clinical features, especially GS) is observed in not only the TCGA data but also those two external datasets. It is also logical that the performance of the expression profiling is generally better than that of the methylation profiling. The reason is that DNA methylation of epi-TSGs takes part in tumor progression via silencing genes, and the expression level of a gene is simultaneously regulated by other factors, such as miRNAs, beyond the promoter methylation status.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by NIH grants 2G12MD007595, 5P20GM103424-15, 3P20GM103424-15S1, P01CA214091, and U19AG055373, and DOD-ARO grant W911NF-15-1-0510. The used TCGA data reside at https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/legacy-archive/search/f. We thank the three reviewers for their constructive comments.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked advertisement in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention Online (http://cebp.aacrjournals.org/).

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 2014;64:9–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bunz F Principles of cancer genetics. Dordrecht: Springer; 2008. p.xi, 325. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Majumdar S, Buckles E, Estrada J, Koochekpour S. Aberrant DNA methylation and prostate cancer. Curr Genomics 2011;12:486–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weber M, Hellmann I, Stadler MB, Ramos L, Paabo S, Rebhan M, et al. Distribution, silencing potential and evolutionary impact of promoter DNA methylation in the human genome. Nat Genet 2007;39:457–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ehrlich M DNA methylation in cancer: too much, but also too little. Oncogene 2002;21:5400–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holliday R, Ho T. DNA methylation and epigenetic inheritance. Methods 2002;27:179–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim HN, van Oudenaarden A. A multistep epigenetic switch enables the stable inheritance of DNA methylation states. Nat Genet 2007;39:269–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park JY. Promoter hypermethylation in prostate cancer. Cancer Control 2010;17:245–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paz MF, Wei S, Cigudosa JC, Rodriguez-Perales S, Peinado MA, Huang TH, et al. Genetic unmasking of epigenetically silenced tumor suppressor genes in colon cancer cells deficient in DNA methyltransferases. Hum Mol Genet 2003;12:2209–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kazanets A, Shorstova T, Hilmi K, Marques M, Witcher M. Epigenetic silencing of tumor suppressor genes: paradigms, puzzles, and potential. Biochim Biophys Acta 2016;1865:275–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kandoth C, McLellan MD, Vandin F, Ye K, Niu B, Lu C, et al. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature 2013; 502:333–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo S, Diep D, Plongthongkum N, Fung HL, Zhang K, Zhang K. Identification of methylation haplotype blocks aids in deconvolution of heterogeneous tissue samples and tumor tissue-of-origin mapping from plasma DNA. Nat Genet 2017;49:635–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eckhardt F, Lewin J, Cortese R, Rakyan VK, Attwood J, Burger M, et al. DNA methylation profiling of human chromosomes 6, 20 and 22. Nat Genet 2006;38:1378–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. The molecular taxonomy of primary prostate cancer. Cell 2015;163:1011–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cristianini N, Shawe-Taylor J. An introduction to support vector machines: and other kernel-based learning methods. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press; 2000. p.xiii, 189. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fraser M, Sabelnykova VY, Yamaguchi TN, Heisler LE, Livingstone J, Huang V, et al. Genomic hallmarks of localized, non-indolent prostate cancer. Nature 2017;541:359–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor BS, Schultz N, Hieronymus H, Gopalan A, Xiao Y, Carver BS, et al. Integrative genomic profiling of human prostate cancer. Cancer Cell 2010; 18:11–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paziewska A, Dabrowska M, Goryca K, Antoniewicz A, Dobruch J, Mikula M, et al. DNA methylation status is more reliable than gene expression at detecting cancer in prostate biopsy. Br J Cancer 2014;111:781–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaz AM, Luo Y, Dzieciatkowski S, Chak A, Willis JE, Upton MP, et al. Aberrantly methylated PKP1 in the progression of Barrett’s esophagus to esophageal adenocarcinoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2012;51: 384–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris MR, Ricketts CJ, Gentle D, McRonald F, Carli N, Khalili H, et al. Genome-wide methylation analysis identifies epigenetically inactivated candidate tumour suppressor genes in renal cell carcinoma. Oncogene 2011;30:1390–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lando M, Fjeldbo CS, Wilting SM, B CS, Aarnes EK, Forsberg MF, et al. Interplay between promoter methylation and chromosomal loss in gene silencing at 3p11-p14 in cervical cancer. Epigenetics 2015;10:970–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang S, Dong Y, Zhang Y, Wang X, Xu L, Yang S, et al. DACT2 is a functional tumor suppressor through inhibiting Wnt/beta-catenin pathway and associated with poor survival in colon cancer. Oncogene 2015;34:2575–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hou J, Liao LD, Xie YM, Zeng FM, Ji X, Chen B, et al. DACT2 is a candidate tumor suppressor and prognostic marker in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Prev Res 2013;6:791–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu-Chittenden Y, Jain M, Gaskins K, Wang S, Merino MJ, Kotian S, et al. RARRES2 functions as a tumor suppressor by promoting beta-catenin phosphorylation/degradation and inhibiting p38 phosphorylation in adrenocortical carcinoma. Oncogene 2017;36:3541–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shames DS, Elkins K, Walter K, Holcomb T, Du P, Mohl D, et al. Loss of NAPRT1 expression by tumor-specific promoter methylation provides a novel predictive biomarker for NAMPT inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:6912–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alderton GK. Tumorigenesis: FBP1 is suppressed in kidney tumours. Nat Rev Cancer 2014;14:575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olvedy M, Tisserand JC, Luciani F, Boeckx B, Wouters J, Lopez S, et al. Comparative oncogenomics identifies tyrosine kinase FES as a tumor suppressor in melanoma. J Clin Invest 2017;127:2310–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greer PA, Kanda S, Smithgall TE. The contrasting oncogenic and tumor suppressor roles of FES. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2012;4:489–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qi G, Kudo Y, Tang B, Liu T, Jin S, Liu J, et al. PARP6 acts as a tumor suppressor via downregulating Survivin expression in colorectal cancer. Oncotarget 2016;7:18812–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buchner A, Castro M, Hennig A, Popp T, Assmann G, Stief CG, et al. Downregulation of HNF-1B in renal cell carcinoma is associated with tumor progression and poor prognosis. Urology 2010;76:507 e6–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rebouissou S, Vasiliu V, Thomas C, Bellanne-Chantelot C, Bui H, Chretien Y, et al. Germline hepatocyte nuclear factor 1alpha and 1beta mutations in renal cell carcinomas. Hum Mol Genet 2005;14:603–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gausachs M, Mur P, Corral J, Pineda M, Gonzalez S, Benito L, et al. MLH1 promoter hypermethylation in the analytical algorithm of Lynch syndrome: a cost-effectiveness study. Eur J Hum Genet 2012;20:762–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Charlet J, Tomari A, Dallosso AR, Szemes M, Kaselova M, Curry TJ, et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis identifies MEGF10 as a novel epigenetically repressed candidate tumor suppressor gene in neuroblastoma. Mol Carcinog 2017;56:1290–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen C, Zhang C, Cheng L, Reilly JL, Bishop JR, Sweeney JA, et al. Correlation between DNA methylation and gene expression in the brains of patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Bipolar Disord 2014;16:790–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zheng Y, Huang Q, Ding Z, Liu T, Xue C, Sang X, et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis identifies candidate epigenetic markers and drivers of hepatocellular carcinoma. Brief Bioinform 2018;19:101–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.D’Antonio M, Ciccarelli FD. Integrated analysis of recurrent properties of cancer genes to identify novel drivers. Genome Biol 2013;14:R52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lawrence MS, Stojanov P, Polak P, Kryukov GV, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko A, et al. Mutational heterogeneity in cancer and the search for new cancer-associated genes. Nature 2013;499:214–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dees ND, Zhang Q, Kandoth C, Wendl MC, Schierding W, Koboldt DC, et al. MuSiC: identifying mutational significance in cancer genomes. Genome Res 2012;22:1589–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu L, Kron KJ, Pethe VV, Demetrashvili N, Nesbitt ME, Trachtenberg J, et al. Association of tissue promoter methylation levels of APC, TGFbeta2, HOXD3 and RASSF1A with prostate cancer progression. Int J Cancer 2011;129:2454–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Phe V, Cussenot O, Roupret M. Methylated genes as potential biomarkers in prostate cancer. BJU Int 2010;105:1364–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Richiardi L, Fiano V, Vizzini L, De Marco L, Delsedime L, Akre O, et al. Promoter methylation in APC, RUNX3, and GSTP1 and mortality in prostate cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:3161–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kron KJ, Liu L, Pethe VV, Demetrashvili N, Nesbitt ME, Trachtenberg J, et al. DNA methylation of HOXD3 as a marker of prostate cancer progression. Lab Invest 2010;90:1060–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mundbjerg K, Chopra S, Alemozaffar M, Duymich C, Lakshminarasimhan R, Nichols PW, et al. Identifying aggressive prostate cancer foci using a DNA methylation classifier. Genome Biol 2017;18:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Geybels MS, Wright JL, Bibikova M, Klotzle B, Fan JB, Zhao S, et al. Epigenetic signature of Gleason score and prostate cancer recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Clin Epigenetics 2016;8:97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao S, Geybels MS, Leonardson A, Rubicz R, Kolb S, Yan Q, et al. Epigenome-wide tumor DNA methylation profiling identifies novel prognostic biomarkers of metastatic-lethal progression in men diagnosed with clinically localized prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:311–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.