Introduction

Combination antiretroviral therapies (ART) suppress HIV replication and improve the health and longevity of people living with HIV (1). The success of ART hinges on persistent adherence, with even the most forgiving ART regimens requiring greater than 80% adherence to minimize the risks of virologic failure (2, 3). Maintaining optimal ART adherence, however, remains a significant challenge for many people living with HIV, with as many as half of people living with HIV in the United States having unsuppressed HIV, the poorest rate of viral suppression among high-income countries (4). A recent meta-analysis found that one in four people who experience challenges to remaining adherent to ART attribute their poor adherence to emotional distress and another one in four attribute their nonadherence to alcohol and other substance misuse (5). Alcohol use is a common correlate of stress and both alcohol use and stress predict ART nonadherence and unsuppressed HIV (6).

Stigma experiences are a common source of stress for people living with HIV and stigma itself is also known to challenge ART adherence (7). Stigma is the social devaluation and discrediting associated with specific characteristics, attributes, and behaviors (8), and stigma is widely regarded as a complex social phenomenon (9, 10). Since the beginning of the HIV epidemic, stigma has undermined treatment efforts (11–15). Stigma impacts the health of people living with HIV through multiple mechanisms including interpersonal relations, psychological resources, mental health and stress (16, 17). Both salient (e.g., discrimination) and subtle (e.g., microaggressions) stigma experiences are potent barriers to seeking health services and adhering to treatment regimens (18–20). Stigma experiences vary across social contexts. For example, stigma occurs to a greater degree in rural areas relative to urban centers (21, 22). A study of HIV stigma experiences in the southeastern US found that lower population density is associated with greater HIV stigma over and above several known predictors of ART adherence including age, education, years since testing HIV positive, and depression symptoms (22). Furthermore, behaviors aimed to avoid stigma by concealing HIV status, such as avoiding clinic visits and hiding medications, create barriers to care and ART adherence (23). HIV-related enacted stigma, specifically social exchanges that people experience as stigma, are therefore among the most robust barriers to engaging in HIV care and adhering to ART (24). Despite decades of stigma research, there are few empirically tested mechanisms to explain how stigma impedes ART adherence.

One potential mechanism by which stigma may impact adherence is stress (25, 26), which in turn can trigger alcohol use as a means of coping, with alcohol use further diminishing adherence (27). Alcohol use is associated with both stress experiences and ART nonadherence (6), and alcohol use mediates the association between emotional distress and ART adherence (28). Katz et al. (29) developed a framework for explaining the impact of enacted stigma on ART adherence. In this model, stigma operates by compromising general psychological processes, particularly impaired coping in response to stress.

The current study extends the framework offered by Katz et al. (29) to examine the association between HIV-related stigma experiences and ART adherence. We specifically tested a serial mediation model, a sequential chain of direct and indirect effects of stigma on ART adherence, to test whether stress and alcohol use explain the effects of stigma on adherence. Our aim was to test a conceptual model grounded in past studies linking stigma to stress, stress to alcohol use, and all three factors to ART adherence. Our study used prospectively collected data to assess cumulative stigma experiences over the course of a year in predicting objectively measured ART adherence. We assessed HIV-related stress as it may co-occur over time with stigma experiences and alcohol use. We tested the hypothesis that the accumulation of HIV stigma experienced over a 12-month period would predict ART adherence and that the association between stigma and adherence would be explained by HIV-related stress and alcohol use.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Men (n = 175) and women (n =76) were recruited from a publicly funded HIV clinic in central Georgia serving a small city and surrounding rural areas between September 2015 and December 2017. Participants were referred by clinic staff if they were returning to care after having fallen out of care for at least 6-momnths or were identified by a provider as either having unsuppressed HIV or at risk for unsuppressed HIV.

During a scheduled office visit, clinic patients were referred to the study and invited to participate. A total of 356 patients were invited to participate and 251 agreed, yielding a 70% response rate. Following informed consent, participants completed the ACASI and provided permission for the researchers to retrieve their electronic medical records. Participants were called monthly for interviews and unannounced pill counts, received 14-day blocks of text assessments with 14-days between blocks. Participants were compensated for their time to complete the study measures over the course of the year with up to $575 cash dispensed via ATM card. The University of Connecticut, Mercer University Medical School and the State of Georgia Department of Health Ethical Review Boards approved all procedures.

Measures

Data were collected through multiple measurement strategies: (a) audio-computer administered self-interviews (ACASI) at a research office; (b) unannounced monthly phone assessments that included interview-administered measures of stigma experiences, HIV-related stress and adherence pill counts; (c) daily text-message assessments of alcohol use; and (d) clinical medical records to obtain HIV viral load. We utilized all sources of data collected within a 12-month period to examine the associations of cumulative stigma experiences, HIV-related stress, alcohol use and ART adherence. To examine cumulative HIV-related enacted stigma, we aggregated stigma events over the course of the 12-monthly interviews. Stigma is highly impactful and experienced sporadically (30, 31). The rationale for aggregating stigma experiences was to test their cumulative occurrence as having lasting impacts extending beyond the month in which they occurred. For HIV-related stress, stressful events were assessed in relation to changes in health, healthcare and relationships. Stress was referenced to the previous month and aggregated to yield a single stress score that was non-overlapping and occurred in the same timeframe as stigma experiences. Alcohol use was measured using 28 days of text-based daily assessments. Alcohol use is a frequent behavior for heavier drinkers, and quantity and frequency data collected daily is more reliable than alcohol use collected for extended retrospective periods (32). We used 28 days of alcohol use collected over a 42-day period that overlapped with ART adherence because the effects of alcohol use on adherence is contemporaneous (33). Finally, ART adherence was computed for the final 3-months of unannounced pill count adherence assessments. We used this 3-month period to provide stable estimates of both adherence and alcohol use as they occurred at the end of the observation period for cumulative stigma experiences.

Audio-computer administered self-interviews

Demographic and health characteristics.

We collected participant demographic characteristics (i.e., gender, sexual orientation, race, age, years of education, etc.), and the year and place they tested HIV positive. Participants also completed the full 20-item CESD Centers for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CESD) to assess symptoms of depression (34). Items focused on how often participants had specific depression-related thoughts, feelings and behaviors in the last seven days. Responses were 0 = 0 days, 1 = 1–2 days, 2 = 3–4 days, and 3= 5–7 days. Scores range from 0 to 60 and scores greater than 16 indicate possible depression, alpha = .90.

Anticipated and Enacted Stigma.

Included in the baseline ACASI were measures of anticipated and enacted stigma, assessed using an adaptation of the HIV Stigma Mechanisms Scale (35, 36). We used nine items to assess participant expectation that they will experience stigma in the future (anticipated stigma) and seven items regarding past experiences of stigma (enacted stigma). We purposefully selected a broad array of stigma experiences to reflect family relationships, experiences of discrimination, and denial of services including health care. For anticipated stigma, participants were asked whether they believe each source of stigma will be experienced in the future. Participants were specifically directed to think about what they believe may happen in the future and respond to each item as to whether they believe it will occur, Yes or No. Two example items for anticipated stigma are: “Because of my HIV status, family members will look down on me”, and “Because of my HIV status, health care workers will treat me with less respect”. Participants were also asked whether they had experienced each of seven enactments of stigma, Yes or No. The seven enacted stigma items are shown in the results. For the baseline assessment, no time constraints were placed on having had these experiences. Stigma experiences were also collected in the subsequent monthly phone interviews with reference to the previous month (see below). For both baseline stigma scales, responses were averaged to create composite scores for anticipated and enacted stigma, alphas .84 and .79, respectively.

Medical records abstracted HIV viral load

Lab reports of blood plasma HIV viral load most proximal and within three months of the research office baseline assessment were abstracted from electronic medical records. In accordance with HIV treatment guidelines (37), we used the clinically recorded value with a threshold to define unsuppressed (detectable) viral load as >20 copies/mL.

Monthly phone interviews of enacted stigma, HIV-related stress and ART adherence

Monthly Enacted Stigma.

We administered the same seven-item enacted stigma scale described above at each of twelve-monthly phone assessments. Stigma experiences were asked about for the preceding 30 days. We used the sum of stigma experiences for all available assessments to create a cumulative composite score representing the frequency of the seven stigma experiences occurring during the course of the 12-months of assessment. The scores had a potential range of 0 to 84.

HIV-Related Stress.

We assessed the experience of HIV-related stressful life events as they may have occurred over the previous month collected at three timepoints over the study year; 4-month, 8-month, and 10-month assessments. The instructions for this scale involved responding Yes or No as to whether each of 12-life events had occurred, and for those that did occur, participants provided a stressfulness rating, 0 = No Stress, 1 = A Little Stress, and 2 = A lot of Stress. The scale was adapted from previous research (38), and included stressful events related to changes in health, healthcare and relationships. We computed a mean composite score to create the HIV-related stress index with a potential range of 0 to 72, with higher scores indicating a greater stress experienced, alpha .86.

HIV treatment and adherence.

We determined whether participants were currently receiving ART by clinic medical records and prescription data and conducted monthly unannounced pill counts, which have been demonstrated reliable and valid in assessing HIV treatment adherence when conducted in participants’ homes and on the telephone (39, 40). Unannounced pill counts conducted over the telephone require counting ability but do not require mental calculation (41). Following an office-based training in the pill counting procedure, participants were called at unscheduled times by a phone assessor. The pill count was repeated three times with 30– 35-day intervals between calls to calculate adherence. Pharmacy information from pill bottles was also collected to verify the number of pills dispensed between calls. Adherence was calculated as the ratio of pills counted relative to pills prescribed and dispensed. Adherence data reported here represents the averaged percentage of all antiretroviral pills taken as prescribed in the three final months of the study, months 10-to-12 following the baseline computerized assessment. Adherence values range from 0 to 100%.

Daily alcohol use text-assessments

Participants received daily text message surveys delivered to their phone for a series of 14 consecutive days with a 14-day off-period between assessment blocks. The questions delivered via texting service referred to alcohol use during the previous day. The measure of alcohol use was modeled after the first item of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test [AUDIT, (42, 43)] and has been used in past research to assess alcohol use in daily text message assessments (44). Specifically, participants were asked “How many alcohol drinks did you have yesterday? If you did not drink say 0” with responses representing the number of drinks consumed that day (e.g., quantity of alcohol use). For the current study, we used the two blocks of assessments (28 days) occurring in the final three months of the study and therefore in the same timeframe as ART adherence. Alcohol use therefore represents mean number of drinks consumed over 28 days proximal to ART adherence. Studies have demonstrated that aggregated day-level assessments of high-frequency behaviors yield more valid and reliable estimates than recalled behavior across retrospective time periods (32). Scores ranged from 0 (no drinks consumed) to 104 drinks consumed over the 28 days.

Data Analyses

We conducted descriptive analyses based on participant enacted stigma experiences over the 12-month observation period. Participants who had not experienced any enactments of stigma over the course of the year (N = 121) were compared to those who had experienced at least one occurrence of enacted stigma (N = 109) on demographic and health characteristics, including ART adherence, stress and alcohol use. Contingency table X2 tests examined differences in categorical variables and analysis of variance (ANOVA) F-tests for continuous variables. Bivariate associations among variables tested in regression models were examined with Pearson correlation coefficients.

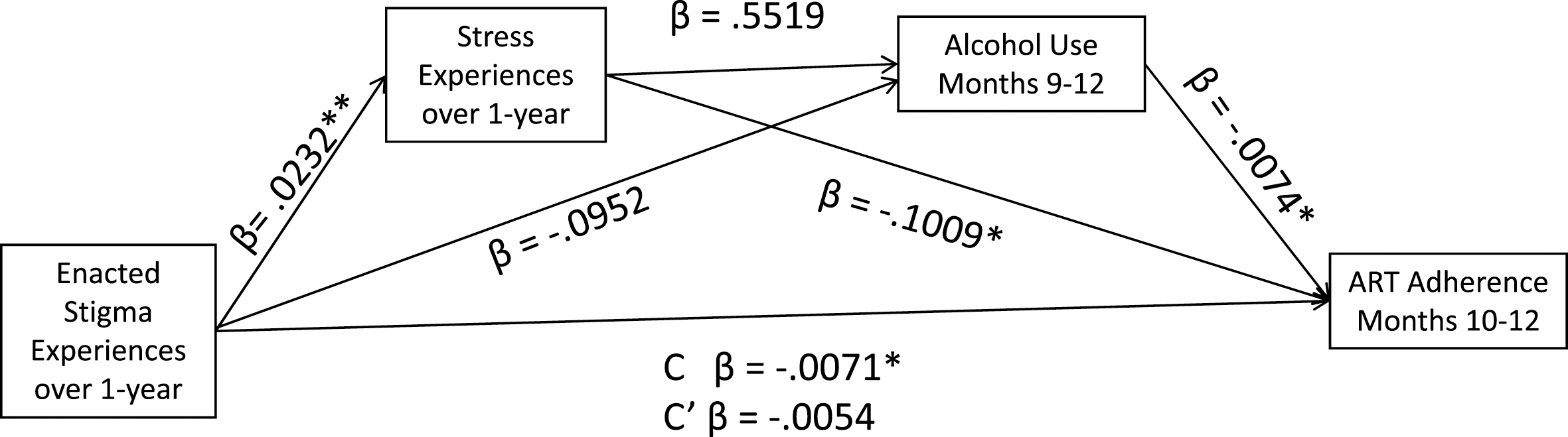

Our main analyses tested the mediation model shown in Figure 1, specifying serial associations between Enacted Stigma → ART Adherence, mediated by Stress → Alcohol use. We used the SPSS PROCESS (v 3.1) macro for mediation analyses to test multiple mediators using bootstrap statistical techniques (45). Multiple mediator models are appropriately analyzed using regression when data are collected over varying timepoints (46). The PROCESS macro estimates all paths designated in the model. Specifically, we used the Model 6 Template for multiple serial mediating variables in an x – y relationship (45). This model tests the effects of the predictor variable (cumulative enacted stigma) on two mediator variables (M1 = HIV-related stress, M2 = alcohol use; representing the a paths), the effects of the mediator variables on the outcome (ART adherence, representing the b paths), and the effects of the predictor variable on the outcome (c path). We report 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the indirect effects of enacted stigma on ART adherence through stress and alcohol use estimated from 5,000 bootstrap resamples.

Figure 1.

Serial mediation model predicting ART adherence from HIV stigma experiences occurring over a one-year period, mediated by HIV-related stress and alcohol use. C’ for the fully mediated serial model, Stigma → Stress → Alcohol Use → ART Adherence.

A second mediation model was tested after trimming non-significant paths. As reported in the results, we tested the more parsimonious model including only stress as a mediator. This model was tested using the PROCESS macro Model 4 Template for a single mediating variable. To examine the robustness of our results, we also repeated the trimmed model with three key covariates, participant gender, years since testing HIV positive, and depression. These control variables were selected to remove confounding effects of known gender disparities among people living with HIV, duration of diagnosis, and depression, all of which may be confounded with stigma, HIV-related stress and ART adherence. Data were available for a total of 230 (91%) participants over the course of the 12-month study period. Missing data for any variables included in the model were deleted case-wise.

Results

The sample included 104 (45%) patients who had fallen out of HIV care and were returning for services, 45 (20%) patients who were newly diagnosed with HIV and were therefore new to HIV care, 69 (30%) patients referred by their physician or nurse due to viral rebound or non-adherence, and 12 (5%) patients who were previously treated by a different clinic and were new to the clinic participating in the study. The sample was predominantly male (68%) and African American (83%). Nearly half (46%) of participants had no sources of employment and 71% had annual incomes under $10,000. On average participants had been living with an HIV diagnosis for more than 10 years, with 40% demonstrating HIV viral suppression from medical chart data. Two out of three participants reported active use of alcohol at baseline and their average depression scores were over the cut-off of 16 for considering probable depression.

Enacted stigma experiences

A total of 109 (47%) participants reported experiencing at least one enacted stigma event over the 12-month observation period. As shown in Table 1, experiencing enacted stigma was associated with younger age and was not associated with any other participant demographic characteristic. Participants who experienced enacted stigma over the year reported more stigma experiences at baseline and greater anticipated stigma at baseline. In addition, participants who experienced enacted stigma also reported more stress and depression at baseline, and were diagnosed with HIV for a shorter time than those not experiencing stigma over 12-months.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants who experienced enacted stigma over twelve months and those not reporting any enacted stigma experiences during that time period.

| Did Not Experience Stigma N = 121 | Experienced Stigma N = 109 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Characteristic | N | % | N | % | X2 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 84 | 69 | 73 | 67 | |

| Female | 37 | 31 | 36 | 33 | 0.15 |

| Transgender | 4 | 3 | 6 | 6 | |

| Sexual orientation | |||||

| Gay | 34 | 28 | 40 | 37 | |

| Bisexual | 9 | 7 | 14 | 13 | |

| Heterosexual | 78 | 65 | 53 | 50 | 5.50+ |

| Race | |||||

| White | 13 | 11 | 17 | 16 | |

| African American | 103 | 85 | 88 | 81 | |

| Other | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3.27 |

| Education level | |||||

| Less than High-School | 39 | 32 | 43 | 39 | |

| High-School or equivalence | 48 | 40 | 41 | 38 | |

| More than High-school | 34 | 28 | 25 | 23 | 6.21 |

| Context of testing HIV positive | |||||

| Rural setting in current state | 66 | 55 | 53 | 49 | |

| Urban setting in current state | 37 | 31 | 45 | 41 | |

| Out of current state | 18 | 14 | 11 | 10 | |

| Was prescribed ART at baseline | 82 | 68 | 75 | 69 | 0.20 |

| Viral load at baseline | |||||

| Undetectable | 47 | 42 | 45 | 45 | |

| Detectable | 66 | 58 | 55 | 55 | 0.20 |

|

|

|||||

| M | SD | M | SD | F | |

|

|

|||||

| Age | 44.4 | 11.9 | 40.4 | 12.0 | 6.4* |

| Years since HIV diagnosis | 13.3 | 9.0 | 10.1 | 7.9 | 7.9** |

| Baseline enacted stigma | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 41.6** |

| Baseline anticipated stigma | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 14.2** |

| Baseline ART adherence | 75.5 | 26.0 | 68.9 | 30.2 | 2.6 |

| Baseline Stress Score | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 11.8** |

| Number of alcohol drinks / day | 4.5 | 15.4 | 1.8 | 6.6 | 2.3 |

| Baseline Depression | 17.9 | 8.8 | 25.1 | 10.2 | 32.0** |

Note:

p < .05

p < .01

p < .10

Table 2 shows the incidence of enacted stigma experiences over the 12-month observation period. The most common occurring stigma experiences were family reactions and acts of discrimination, with the least common experience being participant avoidance of care to conceal their HIV status. The reported number of stigma experiences ranged from 0 to 44. For those experiencing stigma, the median number of enacted stigma experiences was two. As shown in Table 3, there was a clear pattern for participants experiencing more stigma to demonstrate poorer adherence, F = 2.41, p < .05, and greater stress, F = 5.12, p < .05. This pattern was not, however, associated with alcohol use, which showed no relationship to number of stigma experiences, F = 0.89, p > .1.

Table 2.

Annual incidence of enacted HIV stigma experiences among 230 people living with HIV.

| 1–2 occurrences | 3 or more occurrences | Any occurrence in 12-months | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Enacted Stigma Experience | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| Because of your HIV status, did family members avoid you? | 32 | 14 | 11 | 5 | 43 | 19 |

| Because of your HIV status, did family members treat you differently? | 37 | 16 | 14 | 7 | 51 | 23 |

| Did people discriminate against you because of your HIV status? | 40 | 17 | 18 | 8 | 58 | 25 |

| Were you denied services because of your HIV status? | 18 | 8 | 5 | 2 | 23 | 10 |

| Because of your HIV status, did healthcare workers not listen to your concerns? | 35 | 15 | 9 | 4 | 44 | 19 |

| Did you avoid going to a clinic or health care provider because you did not want others to know your HIV status? | 13 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 20 | 9 |

| Did people avoid touching you because of your HIV status? | 24 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 29 | 12 |

| Cumulative enacted stigma experiences | 53 | 23 | 56 | 24 | 109 | 47 |

Note: Items shown as presented to participants; Enacted stigma experiences were asked each month and could be reported more than once during the 12-monthly assessments.

Table 3.

Dose-response relationship of annual stigma experiences in relation to ART adherence, alcohol use, and stress among 230 people living with HIV.

| Number of enacted stigma experiences over 12-months | N | % | Mean ART Adherence | Mean Alcohol Days | Mean Stress Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 121 | 53 | 75.7 | 4.6 | 0.5 |

| 1–2 | 53 | 21 | 75.5 | 4.7 | 0.6 |

| 3–4 | 22 | 9 | 74.5 | 0.5 | 0.9 |

| 5–6 | 11 | 5 | 70.8 | 0.1 | 0.7 |

| 7–11 | 11 | 5 | 66.6 | 1.6 | 0.9 |

| 12 + | 12 | 5 | 47.6 | 0.5 | 1.21 |

Bivariate correlations

Pearson correlation coefficients among variables included in the mediation models showed that stigma was negatively correlated with ART adherence (r = −.17, p < .05), positively correlated with HIV-related stress (r = .26, p < .01) and not associated with alcohol use (r = −.08, ns). In addition, adherence was correlated with HIV-related stress (r = −.22, p < .01) and alcohol use (r = −.18, p < .05). Finally, the correlation between stress and alcohol use was not significant (r = .02, ns).

Stress and alcohol use as mediators of the stigma – ART adherence relationship

Results of the paths tested in the hypothesized serial mediation model are shown in Figure 1. The full model was significant in predicting ART adherence, F= 6.11, p < .05, accounting for 10.1% of the adjusted variance. Results showed that cumulative enacted stigma significantly predicted stress, β = 0.0232, t = 3.7, p < .01. However, neither enacted stigma experiences nor stress were associated with alcohol use, β = −0.0952, t = 1.17, p > .1, and β = 0.5519, t = 0.5, p > .1, respectively. The direct effect of stress on adherence was significant, β = −0.1009, t = 2.5, p < .05, as was the direct effect of alcohol use on adherence, β = −0.0074, t = 2.4, p < 05. The total effect of cumulative stigma experiences on ART adherence was also significant, β = −0.0071, t = 2.2, p < .05, whereas the direct effect of cumulative enacted stigma on adherence was not significant, −0.0054, t = 1.6, p > .1. Based on 5,000 bootstrap resamples, the test of indirect effects of stigma on adherence through stress and alcohol use was not significant, b = −0.0001, 95%CI: −0.0005 to 0.0002. However, the indirect effect of stigma on adherence through stress was significant, Stigma →Stress → Adherence, b = −0.0023, 95%CI: −.0050 to −0.0005. Thus, results showed that HIV-related stress and not alcohol use, mediated the association between stigma and ART adherence.

We trimmed the model to test HIV-related stress as a sole mediating variable (see Figure 2). The full model was significant in predicting ART adherence, F = 5.62, p < .01, accounting for 6.0% of the adjusted variance. Results showed that stigma significantly predicted HIV-related stress, β = 0.0248, t = 4.0, p < .01, and stress predicted adherence, β = −0.0972, t = 2.4, p < .05. The total effect of stigma on adherence was significant, β = −0.0072, t = 2.2, p < .05. Once again, the direct effect of stigma on adherence was not significant, −0.0048, t = 1.4, p > .1. Based on 5,000 bootstrap resamples, the test of indirect effects of stigma on adherence through HIV-related stress was significant, Stigma → Stress → Adherence, b = −0.0024, 95%CI: −.0054 to −0.0005.

Figure 2.

Mediation model predicting ART adherence from HIV stigma experiences occurring over one-year, mediated by HIV-related stress. C’ for the mediated model, Stigma → Stress → ART Adherence.

Tests for confounds

Three participants reported their only stigma experience in the final month of the study and therefore only experienced stigma either contemporaneously or following non-adherence. We repeated the analyses with these participant removed with unchanged results for any direct or indirect effects. The final trimmed model predicting adherence with the three participants removed remained significant, F = 5.40, p < .01, accounting for 6.4% of the adjusted variance. Finally, we tested the stress mediation model controlling for participant gender, years since testing HIV positive, and depression. We again found all paths remained significant and neither gender, 0.0851, t = 1.92, p > .05, years since testing HIV positive, −0.0019, t = 0.77, p > .1, nor depression −0.0012, t = 0.56, p > .1 were significantly associated with ART adherence.

Discussion

The current study found 47% of people receiving care from an HIV clinic serving a small city and surrounding rural areas experienced at least one enacted stigma event over a 12-month observation period, with 30% of participants reporting one to four different stigma experiences. While measures differ across studies, the prevalence of stigma experiences in our sample are consistent with national studies of people receiving HIV care (47, 48). The cumulative enacted stigma experiences assessed in this study were acts that have long-term consequences including familial distancing, discrimination, and denial of services (49). The most common stigma experiences among those we assessed were having people discriminate against the participant because they have HIV and having family members who treated them differently because of their HIV status. Participants experiencing stigma were younger and had been living with HIV fewer number of years than those who had not experienced stigma. In addition, people who experienced stigma also experienced more HIV-related stress over the prospective observation period, as well as greater depression at the baseline assessment.

Results showed that cumulative HIV stigma experiences over the year were associated with ART adherence. We found a dose-response relationship between cumulative enacted stigma experiences and ART non-adherence, as well as greater stigma experiences being related to greater HIV-related stress. The effect of stigma on adherence occurred indirectly through stress, such that the total effect of stigma, but not the direct effect, significantly predicted adherence. This pattern of associations demonstrates that stigma impacts adherence by way of stress, even in the absence of a direct effect of stigma experiences on adherence (50, 51). Average adherence in this sample was lower than what is necessary to sustain HIV viral suppression, with participants who reported at least four stigma experiences demonstrating adherence levels at considerable risk for developing treatment resistant virus (3). The complete as well as the trimmed models demonstrated that cumulative stigma predicted adherence through HIV-related stress. These findings partially confirm our hypothesis and render support for Katz et al.’s (29) framework in that psychological processes (e.g., stress) mediate the association between enacted stigma and adaptive behavior (e.g., adherence). Furthermore, these associations were robust in that they remained significant after accounting for the potential confounding of gender, years living with HIV, and depression.

Our hypothesis was also partially disconfirmed as we did not find that alcohol use contributed to the serial mediation model of the effects of stigma on ART adherence. We failed to find any meaningful associations between either cumulative enacted stigma or HIV-related stress and alcohol use. These findings are similar to those reported in another recent study of stigma pathways to ART adherence. Glynn et al (52) examined multiple mediators to explain the relationship between HIV stigma / life stress and health. The study had conceptualized stigma and stress as co-occurring and had initially tested a model of depression and substance use as mediators. However, substance use failed to significantly contribute to the explained variance in health outcomes and did not act as a mediating variable. Substance use was subsequently removed from the model and depression was the sole mediator between HIV stigma and HIV-related health outcomes, that included general health, HIV symptoms and ART adherence. Our study is consistent with these findings.

Alcohol use is a common predictor of ART non-adherence (53–55), and in the current study alcohol use accounted for 8% of the explained variance in ART non-adherence. Nevertheless, alcohol did not contribute to the hypothesized serial mediation and the association between stigma experiences and alcohol use was in the opposite direction of what we expected; greater stigma experiences related to less drinking. Our measures of stigma and stress were both limited in scope to HIV-related experiences, whereas our measure of alcohol use was not. This disjoint between measures may have constrained finding the expected patterns of associations with alcohol use. Our sample also demonstrated relatively low-rates of alcohol consumption, with the majority of participants not drinking at all during the 28-day assessment period, likely restricting the range for potentially contributing to these findings. Future search with samples demonstrating greater alcohol use may help clarify these findings.

Results of the current study should be interpreted in light of its additional methodological limitations. Although we sampled a clinic serving a broad geographical area within a state with high HIV prevalence, the sample was one of convenience and cannot be considered representative of people living with HIV in this region. In addition, the study was conducted in just one state in the southeastern United States, and is therefore further geographically constrained. Although more than 65% of people living with HIV in rural areas of the US reside in southern states and more than half of people living with HIV in Georgia reside outside of major metropolitan areas (56), our sample cannot be assumed presentative of people living with HIV in southern rural states. Our study used a multi-method approach to independently assess stigma, HIV-related stress, alcohol use and ART adherence. Nevertheless, we relied on self-reported measures of stigma, stress, and alcohol use. An advantage to our approach is that while the self-report measures may be prone to reporting biases, the multiple methods, namely computerized interviews, phone interviews, and daily text message assessments, minimize common method-variance and therefore reduce the risk for spurious associations (57). It should also be noted that our relatively small sample size precluded examining potential moderators of associations involving stigma experiences, particularly gender. Finally, the study design was prospective in that we used stigma and stress measures collected over the course of a year to predict alcohol use and adherence during the final three months of the year. These findings should not, however, be considered causal or directional given that we did not model temporal associations among variables. With these limitations in mind, we believe that the current study findings have implications for designing interventions aimed to address AIDS-related stigma to improve ART adherence.

HIV stigma is pervasive and intersects with homophobia, racism, and sexism, and therefore requiring multi-level societal change (58, 59). Correcting misinformation, instituting polices to address homophobia, racism, sexism, and the other roots of structural stigma must remain a focus, while simultaneously addressing the impacts of stigma at the level of affected individuals, namely people living with HIV. Identifying the emotional processes that stem from stigma experiences is a first step to ameliorating the adverse effects of stigma on engaging in healthcare. The cognitive and affective mechanisms of stress are well understood and are amenable to intervention (60–62). Of particular value is cognitive behavioral therapy with its strong evidence-base for improved coping with HIV-related stress, including stigma (63–65). Research on resilience, positive affect, and emotional regulation also offers avenues for directly managing the chronic stress and cumulative effects of enacted stigma (66–69), with evidence that individuals who more effectively manage stigma are more likely to remain engaged in care, adherent to ART and have better clinical outcomes (67, 70). Providers often screen patients for symptoms of depression, anxiety, and social isolation and we recommend screening for a history of HIV stigma as has been suggested for tuberculosis-related stigma (71) and psychiatric stigma (72). Research is therefore needed to develop a reliable and valid HIV stigma screening instrument to better support healthcare providers to engage with patients to provide support in managing the cumulative effects of HIV stigma.

Highlights.

People with HIV experience cumulative stigma with effects contributing to stress.

Family distancing and discrimination impact the health of people with HIV.

Effects of alcohol use on medication adherence are independent of HIV-stigma.

Cumulative HIV stigma impacts HIV treatment adherence through HIV-related stress.

Acknowledgements:

The study was approved by the University of Connecticut Institutional Review Board Protocol H14–184GDPH and all participants gave written informed consent. We appreciate the collaboration of the State of Georgia Heath Department and the Hope Center of Macon Georgia. This project was supported by National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant R01-AA023727.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Taylor BS, Tieu HV, Jones J, Wilkin TJ. CROI 2019: advances in antiretroviral therapy. Top Antivir Med. 2019;27(1):50–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin M, Del Cacho E, Codina C, Tuset M, De Lazzari E, Mallolas J, et al. Relationship between adherence level, type of the antiretroviral regimen, and plasma HIV type 1 RNA viral load: a prospective cohort study. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2008;24(10):1263–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrd KK, Hou JG, Hazen R, Kirkham H, Suzuki S, Clay PG, et al. Antiretroviral Adherence Level Necessary for HIV Viral Suppression Using Real-World Data. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;82(3):245–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kf Foundation. HIV Viral Suppression Rates in the U.S. Lowest Among Comparable High-Income Countries 2019. [Available from: https://www.kff.org/hivaids/slide/hiv-viral-suppression-rate-in-u-s-lowest-among-comparable-high-income-countries/.

- 5.Shubber Z, Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Vreeman R, Freitas M, Bock P, et al. Patient-Reported Barriers to Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS Med. 2016;13(11):e1002183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Algur Y, Elliott JC, Aharonovich E, Hasin DS. A Cross-Sectional Study of Depressive Symptoms and Risky Alcohol Use Behaviors Among HIV Primary Care Patients in New York City. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(5):1423–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turan B, Hatcher AM, Weiser SD, Johnson MO, Rice WS, Turan JM. Framing Mechanisms Linking HIV-Related Stigma, Adherence to Treatment, and Health Outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(6):863–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goffman E Stigma : notes on the management of spoiled identity. 1st Touchstone ed. New York: Simon & Schuster. 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahajan AP, Sayles JN, Patel VA, Remien RH, Sawires SR, Ortiz DJ, et al. Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: a review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. AIDS. 2008;22 Suppl 2:S67–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blake Helms C, Turan JM, Atkins G, Kempf MC, Clay OJ, Raper JL, et al. Interpersonal Mechanisms Contributing to the Association Between HIV-Related Internalized Stigma and Medication Adherence. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(1):238–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sengupta S, Banks B, Jonas D, Miles MS, Smith GC. HIV interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(6):1075–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stangl AL, Lloyd JK, Brady LM, Holland CE, Baral S. A systematic review of interventions to reduce HIV-related stigma and discrimination from 2002 to 2013: how far have we come? Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2013;16(3 Suppl 2):18734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Straten A, Vernon KA, Knight KR, Gomez CA, Padian NS. Managing HIV among serodiscordant heterosexual couples: serostatus, stigma and sex. AIDS Care. 1998;10(5):533–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fife BL, Wright ER. The dimensionality of stigma: a comparison of its impact on the self of persons with HIV/AIDS and cancer. J Health Soc Behav. 2000;41(1):50–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24(6):518–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turan B, Stringer KL, Onono M, Bukusi EA, Weiser SD, Cohen CR, et al. Linkage to HIV care, postpartum depression, and HIV-related stigma in newly diagnosed pregnant women living with HIV in Kenya: a longitudinal observational study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bauer GR. Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Soc Sci Med. 2014;110:10–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eaton LA, Earnshaw VA, Maksut JL, Thorson KR, Watson RJ, Bauermeister JA. Experiences of stigma and health care engagement among Black MSM newly diagnosed with HIV/STI. J Behav Med. 2018;41(4):458–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friedman MR, Bukowski L, Eaton LA, Matthews DD, Dyer TV, Siconolfi D, et al. Psychosocial Health Disparities Among Black Bisexual Men in the U.S.: Effects of Sexuality Nondisclosure and Gay Community Support. Arch Sex Behav. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friedman MR, Sang JM, Bukowski LA, Matthews DD, Eaton LA, Raymond HF, et al. HIV Care Continuum Disparities Among Black Bisexual Men and the Mediating Effect of Psychosocial Comorbidities. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;77(5):451–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonzalez A, Miller CT, Solomon SE, Bunn JY, Cassidy DG. Size matters: community size, HIV stigma, & gender differences. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(6):1205–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalichman S, Katner H, Banas E, Kalichman M. Population Density and AIDS-Related Stigma in Large-Urban, Small-Urban, and Rural Communities of the Southeastern USA. Prev Sci. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalichman S, Katner H, Banas E, Kalichman M. Population Density and AIDS-Related Stigma in Large-Urban, Small-Urban, and Rural Communities of the Southeastern USA. Prev Sci. 2017;18(5):517–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sweeney SM, Vanable PA. The Association of HIV-Related Stigma to HIV Medication Adherence: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of the Literature. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(1):29–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Evangeli M, Wroe AL. HIV Disclosure Anxiety: A Systematic Review and Theoretical Synthesis. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rueda S, Mitra S, Chen S, Gogolishvili D, Globerman J, Chambers L, et al. Examining the associations between HIV-related stigma and health outcomes in people living with HIV/AIDS: a series of meta-analyses. BMJ Open. 2016;6(7):e011453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalichman SC, Grebler T. Stress and poverty predictors of treatment adherence among people with low-literacy living with HIV/AIDS. Psychosom Med. 2010;72(8):810–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hill LM, Golin CE, Gottfredson NC, Pence BW, DiPrete B, Carda-Auten J, et al. Drug Use Mediates the Relationship Between Depressive Symptoms and Adherence to ART Among Recently Incarcerated People Living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(8):2037–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katz IT, Ryu AE, Onuegbu AG, Psaros C, Weiser SD, Bangsberg DR, et al. Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: systematic review and meta-synthesis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(3 Suppl 2):18640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Earnshaw V, Kalichman SC. Stigma Experienced by People Living with HIV/AIDS. In: Liamputtong P, editor. Stigma, Discrimination and Living with HIV/AIDS: A Cross-Cultural Perspective. New York: Springer Science; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Logie CH, Wang Y, Lacombe-Duncan A, Wagner AC, Kaida A, Conway T, et al. HIV-related stigma, racial discrimination, and gender discrimination: Pathways to physical and mental health-related quality of life among a national cohort of women living with HIV. Prev Med. 2018;107:36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Conner TS, Barrett LF. Trends in ambulatory self-report: the role of momentary experience in psychosomatic medicine. Psychosom Med. 2012;74(4):327–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Braithwaite RS, Conigliaro J, McGinnis KA, Maisto SA, Bryant K, Justice AC. Adjusting Alcohol Quantity for Mean Consumption and Intoxication Threshold Improves Prediction of Nonadherence in HIV Patients and HIV-Negative Controls. Alcohol: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Dam NT, Earleywine M. Validation of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale--Revised (CESD-R): pragmatic depression assessment in the general population. Psychiatry Res. 2011;186(1):128–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Earnshaw VA, Chaudoir SR. From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: a review of HIV stigma mechanism measures. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(6):1160–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Earnshaw VA, Smith LR, Chaudoir SR, Amico KR, Copenhaver MM. HIV stigma mechanisms and well-being among PLWH: a test of the HIV stigma framework. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(5):1785–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.International Advisory Panel on HIVCCO. IAPAC Guidelines for Optimizing the HIV Care Continuum for Adults and Adolescents. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2015;14 Suppl 1:S3–S34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kalichman SC, DiMarco M, Austin J, Luke W, DiFonzo K. Stress, social support, and HIV-status disclosure to family and friends among HIV-positive men and women. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26(4):315–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bangsberg DR, Hecht FM, Charlebois ED, Chesney M, Moss A. Comparing objective measures of adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy: Electronic medication monitors and unannounced pill counts. AIDS and Behavior. 2001;5:275–81. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalichman SC, Amaral C, Swetsze C, Eaton L, Kalichman MO, Cherry C, et al. Monthly unannounced pill counts for monitoring HIV treatment adherence: tests for self-monitoring and reactivity effects. HIV Clin Trials. 2010;11(6):325–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kalichman SC, Amaral CM, Cherry C, Flanagan J, Pope H, Eaton L, et al. Monitoring medication adherence by unannounced pill counts conducted by telephone: reliability and criterion-related validity. HIV Clin Trials. 2008;9(5):298–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maisto SA, Conigliaro J, McNeil M, Kraemer K, Kelley ME. An empirical investigation of the factor structure of the AUDIT. Psychol Assess. 2000;12(3):346–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, DeLaFuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption II. Addictions. 1993;88(6):791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pellowski JA, Kalichman SC, Kalichman MO, Cherry C. Alcohol-antiretroviral therapy interactive toxicity beliefs and daily medication adherence and alcohol use among people living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2016;28(8):963–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hayes AF. Model Templates for PROCESS for SPSS and SAS: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Judd CM, Kenny DA. Process analysis: Estimating mediation in treatment evaluations. Evaluation Review. 1981;5(5):602–19. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baugher AR, Beer L, Fagan JL, Mattson CL, Freedman M, Skarbinski J, et al. Prevalence of Internalized HIV-Related Stigma Among HIV-Infected Adults in Care, United States, 2011–2013. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(9):2600–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Williams EC, Joo YS, Lipira L, Glass JE. Psychosocial stressors and alcohol use, severity, and treatment receipt across human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status in a nationally representative sample of US residents. Subst Abus. 2017;38(3):269–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Earnshaw VA, Chaudoir SR. From Conceptualizing to Measuring HIV Stigma: A Review of HIV Stigma Mechanism Measures. AIDS Behav. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao X, Lynch J, Chen Q Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and Truths about Mediation Analysis. Journal of Consumer Research. 2010;37(2):197–206. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meule A Contemporary Understanding of Mediation Testing. Meta-Psychology. 2019;3:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Glynn TR, Llabre MM, Lee JS, Bedoya CA, Pinkston MM, O’Cleirigh C, et al. Pathways to Health: an Examination of HIV-Related Stigma, Life Stressors, Depression, and Substance Use. Int J Behav Med. 2019;26(3):286–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cohn SE, Jiang H, McCutchan JA, Koletar SL, Murphy RL, Robertson KR, et al. Association of ongoing drug and alcohol use with non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy and higher risk of AIDS and death: results from ACTG 362. AIDS Care. 2011;23(6):775–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morojele NK, Kekwaletswe CT, Nkosi S. Associations between alcohol use, other psychosocial factors, structural factors and antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence among South African ART recipients. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(3):519–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Parsons JT, Rosof E, Mustanski B. Medication adherence mediates the relationship between adherence self-efficacy and biological assessments of HIV health among those with alcohol use disorders. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(1):95–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS statistics and surveillance 2015. [Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/basic.htm#hivaidsexposure

- 57.Sharma R, Yetton P, Crawford J Estimating the Effect of Common Method Variance: The Method—Method Pair Technique with an Illustration from TAM Research. MIS Quarterly. 2009;33(3):473–90. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shacham E, Rosenburg N, Onen NF, Donovan MF, Overton ET. Persistent HIV-related stigma among an outpatient US clinic population. Int J STD AIDS. 2015;26(4):243–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chan BT, Tsai AC. HIV stigma trends in the general population during antiretroviral treatment expansion: analysis of 31 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, 2003–2013. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(5):558–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Scott-Sheldon LA, Kalichman SC, Carey MP, Fielder RL. Stress management interventions for HIV+ adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, 1989 to 2006. Health Psychol. 2008;27(2):129–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Antoni MH, Cruess DG, Klimas N, Carrico AW, Maher K, Cruess S, et al. Increases in a marker of immune system reconstitution are predated by decreases in 24-h urinary cortisol output and depressed mood during a 10-week stress management intervention in symptomatic HIV-infected men. J Psychosom Res. 2005;58(1):3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gonzalez JS, Penedo FJ, Antoni MH, Duran RE, McPherson-Baker S, Ironson G. Social support, positive states of mind, and HIV treatment adherence in men and women living with HIV/AIDS. Health Psychology. 2004;23:413–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Berger S, Schad T, von Wyl V, Ehlert U, Zellweger C, Furrer H, et al. Effects of cognitive behavioral stress management on HIV-1 RNA, CD4 cell counts and psychosocial parameters of HIV-infected persons. AIDS. 2008;22(6):767–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Antoni MH, Carrico AW, Duran RE, Spitzer S, Penedo F, Ironson G, et al. Randomized clinical trial of cognitive behavioral stress management on human immunodeficiency virus viral load in gay men treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy. Psychosom Med. 2006;68(1):143–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Carrico AW, Antoni MH, Duran RE, Ironson G, Penedo F, Fletcher MA, et al. Reductions in depressed mood and denial coping during cognitive behavioral stress management with HIV-Positive gay men treated with HAART. Ann Behav Med. 2006;31(2):155–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Abu-Raiya H, Pargament KI, Krause N, Ironson G. Robust links between religious/spiritual struggles, psychological distress, and well-being in a national sample of American adults. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2015;85(6):565–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ironson G, Kremer H, Lucette A. Relationship Between Spiritual Coping and Survival in Patients with HIV. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(9):1068–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kremer H, Ironson G, Kaplan L, Stuetzele R, Baker N, Fletcher MA. Spiritual coping predicts CD4-cell preservation and undetectable viral load over four years. AIDS Care. 2015;27(1):71–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kremer H, Ironson G, Kaplan L, Stuetzle R, Fletcher MA. Compassionate Love as a Predictor of Reduced HIV Disease Progression and Transmission Risk. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:819021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lyons A, Hosking W, Rozbroj T. Rural-urban differences in mental health, resilience, stigma, and social support among young Australian gay men. J Rural Health. 2015;31(1):89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.de Almeida Crispim J, da Silva LMC, Yamamura M, Popolin MP, Ramos ACV, Arroyo LH, et al. Validity and reliability of the tuberculosis-related stigma scale version for Brazilian Portuguese. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Catthoor K, Schrijvers D, Hutsebaut J, Feenstra D, Sabbe B. Psychiatric Stigma in Treatment-Seeking Adults with Personality Problems: Evidence from a Sample of 214 Patients. Front Psychiatry. 2015;6:101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]