Abstract

Background

Post‐caesarean section infection is a cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. Administration of antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended for preventing infection after caesarean delivery. The route of administration of antibiotic prophylaxis should be effective, safe and convenient. Currently, there is a lack of synthesised evidence regarding the benefits and harms of different routes of antibiotic prophylaxis for preventing infection after caesarean section.

Objectives

The aim of this review was to assess the benefits and harms of different routes of prophylactic antibiotics given for preventing infectious morbidity in women undergoing caesarean section.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (31 January 2016), ClinicalTrials.gov, the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (6 January 2016) and reference lists of retrieved studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing at least two alternative routes of antibiotic prophylaxis for caesarean section (both elective and emergency). Cross‐over trials and quasi‐RCTs were not eligible for inclusion.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trials for inclusion, assessed the risk of bias and extracted data from the included studies. These steps were checked by a third review author.

Main results

We included 10 studies (1354 women). The risk of bias was unclear or high in most of the included studies.

All of the included trials involved women undergoing caesarean section whether elective or non‐elective.

Intravenous antibiotics versus antibiotic irrigation (nine studies, 1274 women)

Nine studies (1274 women) compared the administration of intravenous antibiotics with antibiotic irrigation. There were no clear differences between groups in terms of this review's maternal primary outcomes: endometritis (risk ratio (RR) 0.95, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.70 to 1.29; eight studies (966 women) (low‐quality evidence)); wound infection (RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.17 to 1.43; seven studies (859 women) (very low‐quality evidence)). The outcome of infant sepsis was not reported in the included studies.

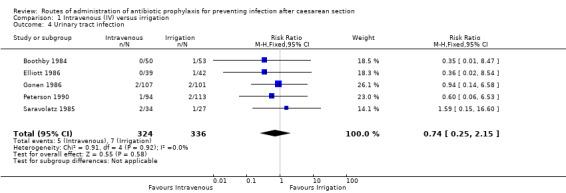

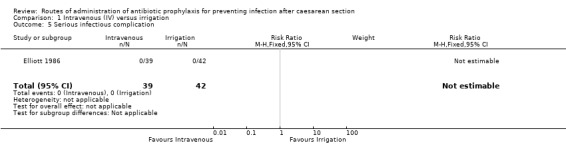

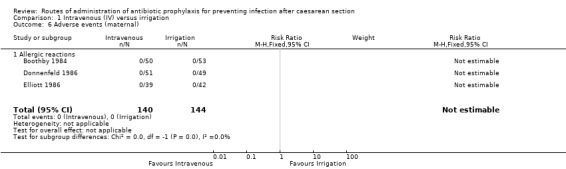

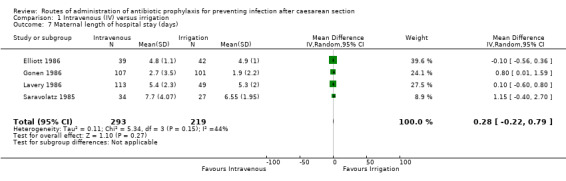

In terms of this review's maternal secondary outcomes, there were no clear differences between intravenous antibiotic or irrigation antibiotic groups in terms of postpartum febrile morbidity (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.60; three studies (264 women) (very low‐quality evidence)); or urinary tract infection (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.25 to 2.15; five studies (660 women) (very low‐quality evidence)). In terms of adverse effects of the treatment on the women, no drug allergic reactions were reported in three studies (284 women) (very low‐quality evidence), and there were no cases of serious infectious complications reported (very low‐quality evidence). There was no clear difference between groups in terms of maternal length of hospital stay (mean difference (MD) 0.28 days, 95% CI ‐0.22 to 0.79 days, (random‐effects analysis), four studies (512 women). No data were reported for the number of women readmitted to hospital. For the baby, there were no data reported in relation to oral thrush, infant length of hospital stay or immediate adverse effects of the antibiotics on the infant.

Intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis versus oral antibiotic prophylaxis (one study, 80 women)

One study (80 women) compared an intravenous versus an oral route of administration of prophylactic antibiotics, but did not report any of this review's primary or secondary outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

There was no clear difference between irrigation and intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis in reducing the risk of post‐caesarean endometritis. For other outcomes, there is insufficient evidence regarding which route of administration of prophylactic antibiotics is most effective at preventing post‐caesarean infections. The quality of evidence was very low to low, mainly due to limitations in study design and imprecision. Furthermore, most of the included studies were underpowered (small sample sizes with few events). Therefore, we advise caution in the interpretation and generalisability of the results.

For future research, there is a need for well‐designed, properly‐conducted, and clearly‐reported RCTs. Such studies should evaluate the more recently available antibiotics, elaborating on the various available routes of administration, and exploring potential neonatal side effects of such interventions.

Plain language summary

What is the most effective and safe way to administer antibiotics to prevent infection for women undergoing caesarean section

What is the issue?

Caesarean delivery increases the risk for infection compared to vaginal birth by five‐ to 20‐fold. Infections can be of the surgical incision, the lining of the uterus, and inside the pelvis. Clinicians seek to prevent these infections by different measures including prophylactic (preventative) antibiotics.

Why is this important?

Antibiotics can be given by a number of different routes including by mouth, injection into a vein or by washing inside the uterus and the surgical site with a saline solution containing the antibiotic. We assessed the benefits and harms of different routes of prophylactic antibiotics given for preventing infections in women undergoing caesarean section.

What evidence did we find?

We searched for evidence from randomised controlled trials on 6 January 2016 and found 10 studies (involving a total of 1354 women).

Nine studies (1274 women) compared intravenous antibiotic administration with antibiotic irrigation (washing with a saline solution containing antibiotics). The two routes gave similar results on important outcomes including infection of the uterus/womb (low‐quality evidence) and wound infection (very low‐quality evidence). The studies did not report on blood infections in the newborn infant (sepsis). The numbers of women who had urinary tract infection (very low‐quality evidence), serious infectious complications (very low‐quality evidence) or fever after birth (very low‐quality evidence) also did not clearly differ between groups. There was no clear difference between groups in terms of how long women spent in hospital and no data reported on the number of women who were readmitted to hospital. No women had allergic reactions to the antibiotics (very low‐quality evidence) in the three studies that reported this outcome. None of the studies reported information about whether the babies had any immediate adverse reactions to the antibiotics.

One study (involving 80 women) compared intravenous antibiotics with taking antibiotics orally but it did not report on any of this review's outcomes.

What does this mean?

The studies included in this review did not clearly report how they were carried out and outcome data were incomplete. Too few women were included in each study for sufficient numbers of events to see a clear difference in outcomes between the two groups of women. This meant the evidence was of low quality. Therefore, we need to exercise caution in the interpretation and generalisability of the results.

High‐quality studies are needed to determine the safest, most effective way of giving preventive antibiotics. Such studies should evaluate more recently available antibiotics and consider potential side effects that the intervention may have for the baby.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Intravenous route compared with irrigation (lavage) for administration of antibiotic prophylaxis for preventing infection after caesarean section.

| Intravenous route compared with irrigation (lavage) for administration of antibiotic prophylaxis for preventing infection after caesarean section | ||||||

| Patient or population: pregnant women undergoing caesarean section Setting: hospital in‐patients Intervention: intravenous route of prophylactic antibiotics Comparison: irrigation (lavage) containing antibiotics | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with irrigation | Risk with Intravenous route | |||||

| Endometritis | 142 per 1000 | 135 per 1000 (99 to 183) | RR 0.95 (0.70 to 1.29) | 966 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | |

| Wound infection | 21 per 1000 | 10 per 1000 (4 to 30) | RR 0.49 (0.17 to 1.43) | 859 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 3 | |

| Postpartum febrile morbidity | 138 per 1000 | 120 per 1000 (66 to 222) | RR 0.87 (0.48 to 1.60) | 264 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 3 | |

| Urinary tract infection | 21 per 1000 | 15 per 1000 (5 to 45) | RR 0.74 (0.25 to 2.15) | 660 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 3 | |

| Serious infectious complications | 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | not estimable | 81 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 4 | No events in one study. |

| Adverse events (maternal) | 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | not estimable | 284 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 5 | No events in three studies. |

| Infant sepsis (suspected or proven) ‐ not measured | see comment | see comment | not estimable | ‐ | ‐ | Not measured by any of the included studies |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Studies with design limitations (‐1)

2 Optimal information size criterion is not met and the 95% confidence interval includes no effect (‐1)

3 Studies include relatively few patients and few events and have a wide 95% confidence interval that includes both appreciable benefit and appreciable harm (‐2)

4 One study with no events (‐2)

5 Three studies with no events (‐2)

Background

Caesarean section is probably the most commonly performed major obstetric procedure, and rates are increasing globally. Although, it is mostly a straightforward, uncomplicated surgery, caesarean section remains the single most important risk factor for puerperal infection. The incidence of post‐caesarean infection varies widely worldwide, ranging from 2.5% to 20.5% (Conroy 2012). Women undergoing caesarean section have a greater risk of developing infection compared with women who have a vaginal birth by five‐ to 20‐fold (Declercq 2007; Leth 2009).

Description of the condition

Post‐caesarean section infection includes wound infection and endometritis. Additionally, urinary tract infection may be associated with caesarean delivery. In rare cases, pelvic abscess, bacteraemia, septic shock, septic pelvic vein thrombophlebitis, necrotising fasciitis, dehiscence of the wound, or evisceration may occur. The impact of post‐caesarean infections include additional cost, the use of therapeutic antibiotics, additional surgical interventions, longer duration of hospital stay, and in some cases maternal death attributed to infection (Cantwell 2011; Lamont 2011).

Postpartum endometritis

Postpartum endometritis is one of the commonest complicating infections, which can follow an aggressive course, progressing into endomyometritis, up to pelvic abscess or even generalised peritonitis and septicaemia. Caesarean delivery is probably the most important single risk factor for postpartum endometritis, with reported odds ratios ranging between 5 and 20 (Cox 1989; French 2003; French 2004; Olsen 2010).

Wound (surgical site) infection

Wound (surgical site) infection refers to infection of the skin and subcutaneous (SC) tissue at the surgical incision site. A post‐caesarean wound infection detected prior to hospital discharge will lead to prolongation of hospital stay and will increase the hospitalisation costs and need readmission (Griffiths 2005; Nice 1996; Olsen 2008; Roberts 1993; Webster 1988).

Risk factors

Post‐caesarean section infection is associated with obesity (Myles 2002), diabetes (Leth 2011), immunosuppressive disorders, chorioamnionitis, rupture of membranes > 18 hours (Chang 1992; Olsen 2010), corticosteroid therapy, staple suture wound closure, fewer prenatal care visits, repeat caesarean section, emergency caesarean section (Leth 2011), length of surgery > 60 minutes (Killian 2001), a prolonged labour, excessive blood loss during labour, delivery, or surgery, and failure to follow proper steps for wound care after leaving the hospital (Maharaj 2007). Other risk factors include pre‐existing operative site infection, breaks in sterile technique, use of electrocautery, advanced maternal age (Magee 1994), prolonged preoperative admissions, low socioeconomic status, repeated vaginal examinations during labour (Olsen 2008), internal fetal monitoring, urinary tract infection, development of SC haematoma, the skill of the operator, method of placental removal and site of uterine repair (Lasley 1997; Magann 1995; Maharaj 2007).

Causative organism

Post‐caesarean infections are typically polymicrobial infections involving a mixture of gram‐positive and gram‐negative bacteria, anaerobes (including Peptostreptococcus species and Bacteroides species), Gardnerella vaginalis and genital mycoplasmas (Cox 1989; Maharaj 2007; Roberts 1993).

Description of the intervention

There are different interventions that aim to reduce the rate of infection after caesarean delivery including preoperative vaginal preparation with antiseptic solution (Haas 2014) and prophylactic antibiotics (Chelmow 2001; Dinsmoor 2009; Doss 2012; Eriksen 2011; Salim 2011; Smaill 2014).

There are different routes of administration of perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis including injection, oral, rectal, vaginal lavage (Ledger 2006; Liabsuetrakul 2002; Mangram 1999; SIGN 2008; Tita 2009). The route of administration of any drug is determined by its pharmacological properties and by the therapeutic purposes including the need for a rapid onset of action or long‐term treatment. Therefore, the route of administration is a determinant of the serum and tissue drug levels throughout the procedure that should be adequate to prevent post‐caesarean infections. Each route has its advantage and disadvantage (SIGN 2008). Ideally, such a route should be well‐tolerated in addition to its effectiveness.

Natural orifice routes (oral or rectal), provide less invasive routes, but with delayed achievement of target plasma levels. In general, oral administration is the most convenient with the lowest cost. A rapid delivery can be obtained by breaking the tablets or capsules that come in delayed‐ or time‐release formulations. In some individuals, the absorption of antibiotics from the gastrointestinal system and thus the effect of oral administration can be unpredictable. Rectal administration is an easy and relatively painless route that provides rapid absorption of antibiotics.

Antibiotics can be administered intravenously or by intramuscular injection. Intravenous administration provides the quickest route to achieve therapeutic plasma levels and has an onset of action of 15 to 30 seconds. The onset of action for the intramuscular route is 10 to 20 minutes. Most antibiotics have 100% bioavailability when given by injection. Some antibiotics can only be administered by injections because they are either poorly absorbed or ineffective when given orally. Although intravenous infusion is the mode of delivery used most often in perioperative prophylaxis, it can cause complications such as allergic reactions. Injections may cause pain or discomfort. Injections also require a trained caregiver using aseptic techniques for administration (Bratzler 2013; SIGN 2008).

How the intervention might work

The occurrence of wound infection requires local inoculums (material used for inoculation) sufficient to overcome host defences and establish growth. The process is complex and depends on the interaction of various hosts, local tissue and microbial virulence factors. Antibiotic prophylaxis does not attempt to sterilise tissues, but to reduce the intraoperative microbial burden. Therefore, the key for effective prophylaxis is to achieve serum and tissue drug levels that exceed the minimum inhibitory concentration for the likely causative organisms during the operation (Conte 2002; Mangram 1999).

There is insufficient empirical evidence to show that the parenteral route is more effective than other routes, whether in prophylaxis or treatment in terms of rates of improvement, failure, or relapse of infection. The perception that parenteral injections are more effective or have an added effect is not supported by empirical evidence and is an inadequate reason to choose injection when oral or rectal antibiotics are less expensive, less painful, and have fewer serious side effects (Borahay 2011). As the clinical and economic impact of post‐caesarean infections is considerable, an affordable convenient route of administration is also required (Chelmow 2004; Cooper 2002).

Why it is important to do this review

In view of concerns about post‐caesarean section infection as a cause of direct maternal morbidity and mortality, the specific questions regarding the best evidence for antibiotic prophylaxis, the class of antibiotic, the dose, the timing, and the route of administration must be answered. The questions regarding antibiotic prophylaxis (Smaill 2014), the class of antibiotics (Gyte 2014), the timing of intravenous antibiotics (Mackeen 2014) and regimens of penicillin antibiotics (Liu 2014), for caesarean section are tackled in other Cochrane reviews. Evidence regarding antibiotic prophylaxis is based on high‐quality studies comparing intravenous antibiotics with placebo or no therapy. Currently, there is a lack of synthesised evidence regarding the benefits and harms of different routes of administration of antibiotic prophylaxis for preventing infection after caesarean section. The route of administration of antibiotic prophylaxis should be effective, safe, inexpensive, and convenient for both the woman and her physician.

Therefore, the current review specifically focuses on the following question: in women undergoing caesarean delivery and receiving antibiotic prophylaxis, which route is most effective at preventing post‐caesarean infections?

Objectives

The aim of this review is to assess the benefits and harms of different routes of prophylactic antibiotics given to prevent infectious morbidity in women undergoing caesarean section.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all published and unpublished randomised controlled trials (RCTs) where the intention was to allocate participants randomly to one of at least two alternative routes of antibiotic prophylaxis for caesarean section. Ongoing RCTS and cluster‐randomised RCTs were eligible for inclusion but none were identified. We planned to exclude trials presented only as abstracts where information on risk of bias and primary or secondary outcomes could not be obtained and planned to reconsider these trials for inclusion once the full publication was available. Cross‐over trials and quasi‐RCTs were not eligible for inclusion in this review.

Types of participants

Women undergoing elective or emergency caesarean section.

Types of interventions

Prophylactic antibiotic regimens comparing different routes of antibiotics. We included studies where there was a comparison between two or more antibiotics from the different classes of antibiotics. Different drugs within the same class of antibiotics were used for subgroup analysis.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Maternal

Endometritis

Wound infection

Infant

Infant sepsis (suspected or proven)

Secondary outcomes

Maternal

Postpartum febrile morbidity

Urinary tract infection

Serious infectious complication (such as bacteraemia, septic shock, septic thrombophlebitis, necrotising fasciitis, or death attributed to infection)

Adverse effects of treatment on the woman (e.g. allergic reactions, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, skin rashes)

Maternal length of hospital stay

Readmissions

Infant

Oral thrush

Infant length of hospital stay

Immediate adverse effects of antibiotics on the infant

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group. The review is based on a published protocol (Nabhan 2015).

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (31 January 2016).

The Register is a database containing over 21,000 reports of controlled trials in the field of pregnancy and childbirth. For full search methods used to populate the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register including the detailed search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL; the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service, please follow this link to the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group in the Cochrane Library and select the ‘Specialized Register ’ section from the options on the left side of the screen.

Briefly, the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE (Ovid);

weekly searches of Embase (Ovid);

monthly searches of CINAHL (EBSCO);

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Search results are screened by two people and the full text of all relevant trial reports identified through the searching activities described above is reviewed. Based on the intervention described, each trial report is assigned a number that corresponds to a specific Pregnancy and Childbirth Group review topic (or topics), and is then added to the Register. The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the Register for each review using this topic number rather than keywords. This results in a more specific search set which has been fully accounted for in the relevant review sections (Included studies; Excluded studies; Studies awaiting classification).

In addition, we searched ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (6 January 2016) for unpublished, planned and ongoing trial reports (see Appendix 1 for search strategy).

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of retrieved studies. We did not apply any language or date restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Selection of studies

Two review authors (NA and MH) independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies we identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted the third review author (AN). We created a study flow diagram to map out the number of records identified, included and excluded.

Data extraction and management

We designed a computer form to extract data. For eligible studies, at least two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted the third member of the review team. We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2014) and checked for accuracy. When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact the authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreement by discussion or by involving the third review author.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding would be unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we planned to re‐include missing data in the analyses which we undertook.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

For missing data, a cut‐off point of 20% was used to assess that a study was at low risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described for each included study any important concerns we have about other possible sources of bias including: was the trial stopped early due to some data‐dependent process? Was there extreme baseline imbalance? Has the study been claimed to be fraudulent?

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

low risk of other bias;

high risk of other bias;

unclear whether there is risk of other bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we consider it was likely to impact on the findings. We explored the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Assessing the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach

We assessed the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach as outlined in the GRADE handbook in order to assess the quality of the body of evidence relating to the following outcomes for the main comparisons.

Endometritis

Wound infection

Postpartum febrile morbidity

Urinary tract infection

Serious infectious complication

Adverse effects of treatment on the woman

Infant sepsis (suspected or proven)

We used the GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool to import data from Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan 2014) in order to create a 'Summary of findings’ table (see Table 1). A summary of the intervention effect and a measure of quality for each of the above outcomes were produced using the GRADE approach. The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome. The evidence can be downgraded from 'high quality' by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments for risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates or potential publication bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we used the mean difference as outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We planned to use the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measured the same outcome, but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We did not identify any cluster‐randomised trials for inclusion in this version of the review. In future updates, if we identify any cluster‐randomised trials, we will adjust their sample sizes using the methods described in the Handbook [Section 16.3.4 or 16.3.6] using an estimate of the intra‐cluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely. We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Multi‐armed trials

We anticipated the presence of multi‐armed studies, therefore we combined groups of similar routes to create a single pair‐wise comparison.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition and contacted the study authors, but we failed to obtain additional data. For all outcomes, we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses, and all participants were analysed in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. The denominator for each outcome in each trial were the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Finally, we explored the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if an I² was greater than 30% and either a Tau² was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

In future updates of this review, if we include 10 or more studies in a meta‐analysis, we will investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry is suggested by a visual assessment, we will perform exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2014). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials were examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods were judged sufficiently similar. If there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity was detected, we used random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary, if an average treatment effect across trials was considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary was treated as the average of the range of possible treatment effects and we discussed the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect was not clinically meaningful, we did not combine trials.

Where we used random‐effects analyses, the results are presented as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals, and the estimates of Tau² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where we identified substantial heterogeneity, we investigated it using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. We considered whether an overall summary was meaningful, and if it was, used random‐effects analysis to produce it.

We carried out subgroup analysis by dosage as pre‐specified, i.e. single versus multiple. The following outcomes were used in subgroup analysis: maternal primary outcomes (endometritis and wound infection). We assessed subgroup differences by interaction tests available within RevMan (RevMan 2014). We reported the results of subgroup analyses quoting the Chi2 statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² value.

It was not possible to carry out the following planned subgroup analyses due to insufficient data ‐ these will be performed in future updates, if appropriate.

By type of caesarean delivery: elective versus non‐elective versus not defined.

By time of administration: before cord clamping versus after cord clamping versus not defined.

By type of antibiotic in each class of antibiotics.

Sensitivity analysis

We carried out a sensitivity analysis to explore the effects of trial quality assessed by omitting studies rated as 'high risk of bias' and 'unclear risk of bias' when considering incomplete outcome data (attrition bias). We restricted sensitivity analysis to the primary outcomes. We did not carry out sensitivity analysis considering allocation concealment (selection bias) since we judged all included trials to be at an unclear risk of bias. In future updates, if we include cluster‐RCT trials along with individually‐randomised trials in our analyses, we will carry out sensitivity analysis to investigate the effect of the randomisation unit.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

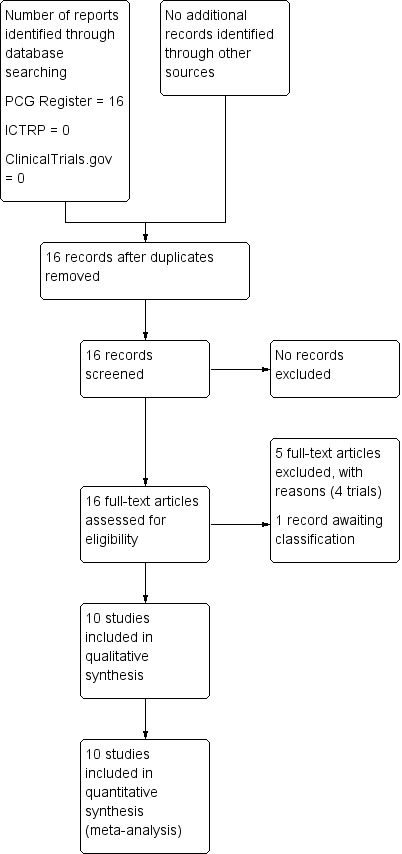

The search of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register retrieved 16 reports (of 15 studies as two records reported a single study). We did not identify any additional reports through other sources. We did not identify any ongoing or unpublished reports (see: Figure 1). Ten studies are included, excluded four studies and one other study (Wu 1992) is awaiting classification pending translation from Chinese (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included 10 studies (involving 1354 women) (Berkeley 1990; Boothby 1984; Donnenfeld 1986; Elliott 1986; Gonen 1986; Lavery 1986; Leveno 1984; Peterson 1990; Saravolatz 1985; Voto 1986). See Characteristics of included studies.

Design

We included 10 randomised controlled trials. All were superiority studies. Seven studies used a standard parallel group design (Berkeley 1990; Boothby 1984; Donnenfeld 1986; Gonen 1986; Leveno 1984; Saravolatz 1985; Voto 1986) and three were 'multi‐arm’ studies (Elliott 1986; Lavery 1986; Peterson 1990).

Sample sizes

The 10 included studies enrolled a total of 1354 women. The sample size ranged from 64 women to 217 with an average of 135 per study.

Setting

All studies enrolled women who were admitted to hospitals for delivery. Studies were conducted in Argentina (Voto 1986), Israel (Gonen 1986) and the USA (Berkeley 1990; Boothby 1984; Donnenfeld 1986; Elliott 1986; Lavery 1986; Leveno 1984; Peterson 1990; Saravolatz 1985). All studies were conducted and reported between 1984 and 1990.

Participants

All studies included in this review enrolled women of reproductive age, whether in labour or not who underwent caesarean delivery. Indications for caesarean delivery reflected the diverse pragmatic practice and included cephalopelvic disproportion, fetal distress, failure to progress, breech presentation, transverse lie, repeat caesarean section, herpes, twins, abruptio placenta, placenta praevia, pre‐eclampsia, and diabetes.

Interventions and comparisons

All studies included in this review compared an intravenous route of administration with other routes.

Nine studies (Berkeley 1990; Boothby 1984; Donnenfeld 1986; Elliott 1986; Gonen 1986; Lavery 1986; Leveno 1984; Peterson 1990; Saravolatz 1985) compared irrigation versus intravenous administration of antibiotic prophylaxis and one study (Voto 1986) compared oral versus intravenous administration. The studies used different antibiotics and dosages.

The intravenous route included cephalosporins (cefamandole, cefazolin, ceforanide, cefotaxime, and cefoxitin) and penicillins (mezlocillin). Studies used different intravenous dosages including single dose (Lavery 1986; Peterson 1990; Saravolatz 1985), multiple doses (Berkeley 1990; Boothby 1984; Donnenfeld 1986; Gonen 1986; Leveno 1984), or continued antibiotics for two days postoperatively (Elliott 1986).

The irrigation route included cephalosporins (cefamandole, cefazolin, ceforanide, cefotaxime, and cefoxitin) and penicillins (mezlocillin) in 500 mL or 1000 mL normal saline) with the technique described in the literature by Long 1980.

The oral route used ampicillin in a dose of 2 g/day taken four times over seven days postoperatively.

Outcomes

The included studies measured the following outcomes: endometritis (or endomyometritis); wound infection (or surgical site infection); urinary tract infection; serious infectious complications included septic pelvic thrombophlebitis and septicaemia; postpartum febrile morbidity; additional antibiotic use; length of postpartum hospitalisation in days (maternal); adverse events included antibiotic induced allergic reactions; pulmonary complications included atelectasis and pulmonary infection; and culture included endometrial, endocervical, subcutaneous, wound and urine culture. Other outcomes included transfusion reactions.

Excluded studies

We excluded four studies (reported in five reports). Three were quasi‐randomised studies (Conover 1984; Itskovitz 1979; Mathelier 1992) and one was a pharmacokinetic study (Flaherty 1983). For further details see the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

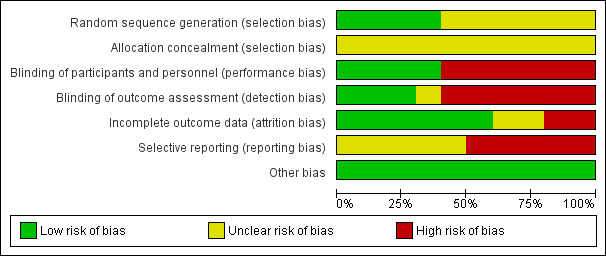

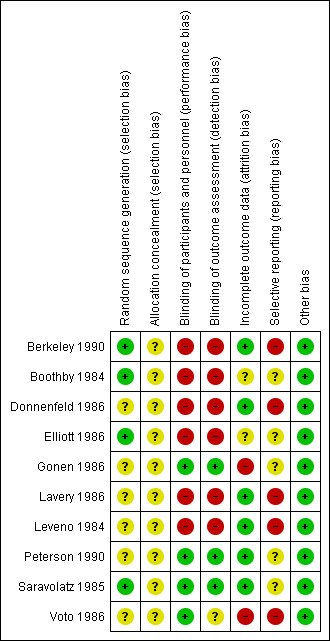

Risk of bias in included studies

We summarised the risk of bias in included studies. Figure 2 is a 'Risk of bias' graph depicting the review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item presented as percentages across all included studies. Figure 3 is a 'Risk of bias' summary showing review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item for each included study.

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Sequence generation

In four studies (Berkeley 1990; Boothby 1984; Elliott 1986; Saravolatz 1985), the investigators described a random component in the sequence generation process and we judged those studies to be at low risk of selection bias. In the other six studies (Donnenfeld 1986; Gonen 1986; Lavery 1986; Leveno 1984; Peterson 1990; Voto 1986), there was Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement of ‘low risk’ or ‘high risk’ and we judged those studies to be at unclear risk of bias.

Allocation concealment

In all included studies, the method of concealment was not described or not described in sufficient detail to allow a definite judgement. Therefore, we judged all included studies to have an unclear risk of selection bias because there was Insufficient information to permit judgement of ‘low risk’ or ‘high risk’.

Blinding

Blinding of participants and personnel was reported in three studies (Gonen 1986; Peterson 1990; Saravolatz 1985) by the use of a double‐dummy technique to overcome the different routes of antibiotic administration. In one study (Voto 1986), blinding was not reported, but we judged that the outcome was not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. Blinding of participants and personnel in the other six studies was not performed and we judged those studies (Berkeley 1990; Boothby 1984; Donnenfeld 1986; Elliott 1986; Lavery 1986; Leveno 1984) to be at high risk of performance and detection bias.

Incomplete outcome data

In six studies (Berkeley 1990; Donnenfeld 1986; Lavery 1986; Leveno 1984; Peterson 1990; Saravolatz 1985) incomplete outcome data appeared to have been adequately addressed and any missing outcome data were reasonably well‐balanced across intervention groups with similar reasons for incomplete data across the groups. In two of the studies (Boothby 1984; Elliott 1986), there was insufficient reporting of attrition/exclusions to permit judgement of ‘low risk’ or ‘high risk’ because the number of women randomised was not stated (both assessed as unclear risk of bias). In two of the studies (Gonen 1986; Voto 1986), the proportion of excluded participants was enough to induce clinically relevant bias in the intervention effect estimate (high risk of bias).

Selective reporting

All included studies were reported between 1984 and 1990. The reporting quality was consistent with the editorial style and standards existing at the time of publication. We could not identify any study with prospective registration, or the protocols for the included studies were not available. In five studies (Boothby 1984; Elliott 1986; Gonen 1986; Peterson 1990; Saravolatz 1985), there was insufficient information to permit judgement of 'low risk' or ‘high risk’, and we therefore judged these studies to be at unclear risk of bias.

Although the protocols for the other five studies were not available (Berkeley 1990; Donnenfeld 1986; Lavery 1986; Leveno 1984; Voto 1986), the reports failed to include results for a key outcome that would be expected to have been reported for such a study, and we judged these studies to be at a high risk of reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

All of the included studies appeared to be free of other forms of bias (low risk of other bias).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

See Table 1 for the comparison of Intravenous route versus irrigation for administration of antibiotic prophylaxis for preventing infection after caesarean section.

We summarised the risk of bias of the included studies in Figure 2 and Figure 3 and judged many studies to be of ’unclear’ or ’high’ risk of bias. Consequently, we need to exercise caution in the interpretation and generalisability of the results.

We described two relevant comparisons.

Intravenous verus irrigation

Intravenous versus oral

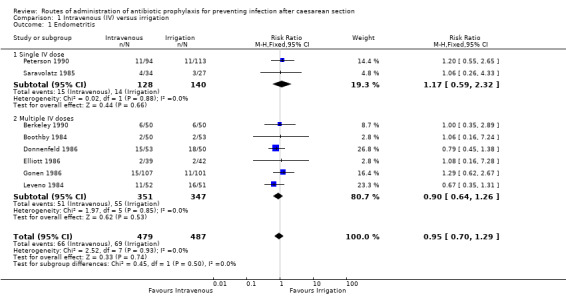

Comparison 1: Intravenous antibiotics versus irrigation with antibiotics (nine studies, 1274 women)

Primary outcomes

Maternal

Endometritis

Eight of the studies (Berkeley 1990; Boothby 1984; Donnenfeld 1986; Elliott 1986; Gonen 1986; Leveno 1984; Peterson 1990; Saravolatz 1985) provided data for this outcome. We found no clear difference between intravenous antibiotics and antibiotic irrigation with regard to our outcome ’endometritis’ (risk ratio (RR) 0.95, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.70 to 1.29, P = 0.74, 966 women (low‐quality evidence)). See Analysis 1.1.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intravenous (IV) versus irrigation, Outcome 1 Endometritis.

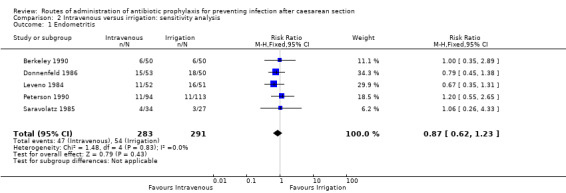

A sensitivity analysis (removing studies that were at a high or unclear risk of attrition bias), does not change the overall result (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.23, five studies, 574 women) See Analysis 2.1.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Intravenous versus irrigation: sensitivity analysis, Outcome 1 Endometritis.

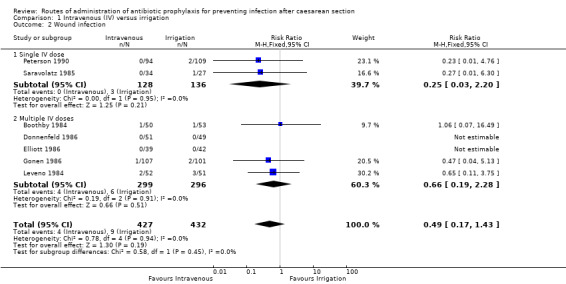

Wound infection

Seven of the studies (Boothby 1984; Donnenfeld 1986; Elliott 1986; Gonen 1986; Leveno 1984; Peterson 1990; Saravolatz 1985) provided data for this outcome. We found no difference between intravenous antibiotics and antibiotic irrigation with regard to our outcome ’wound infection’ (RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.17 to 1.43, P = 0.19, 859 women (very low‐quality evidence)). See Analysis 1.2.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intravenous (IV) versus irrigation, Outcome 2 Wound infection.

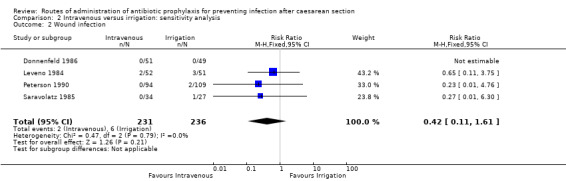

A sensitivity analysis (removing studies at high or unclear risk of attrition bias) does not change the overall result (RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.11, 1.61, four studies, 467 women). See Analysis 2.2.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Intravenous versus irrigation: sensitivity analysis, Outcome 2 Wound infection.

Infant

Infant sepsis (suspected or proven)

This outcome was not reported by any of the studies in this comparison.

Secondary outcomes

Maternal

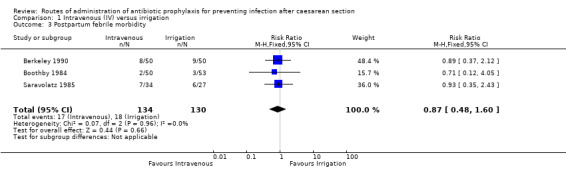

Postpartum febrile morbidity

Three of the studies (Berkeley 1990; Boothby 1984; Saravolatz 1985) provided data for this outcome. We found no difference between intravenous antibiotics and antibiotic irrigation with regard to our outcome ’postpartum febrile morbidity’ (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.60, P = 0.66, 264 women (very low‐quality evidence)). See Analysis 1.3.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intravenous (IV) versus irrigation, Outcome 3 Postpartum febrile morbidity.

Urinary tract infection

Five of the studies (Boothby 1984; Elliott 1986; Gonen 1986; Peterson 1990; Saravolatz 1985) provided data for this outcome. We found no difference between intravenous antibiotics and antibiotic irrigation with regard to our outcome ’urinary tract infection’ (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.25 to 2.15, P = 0.58, 660 caesarean sections (very low‐quality evidence)). See Analysis 1.4.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intravenous (IV) versus irrigation, Outcome 4 Urinary tract infection.

Serious infectious complication

The outcome of septicaemia was reported in one study (81 women) (Elliott 1986), but there were no events (very low‐quality evidence). See Analysis 1.5.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intravenous (IV) versus irrigation, Outcome 5 Serious infectious complication.

Adverse effects of treatment on the woman

Three of the studies (284 women) (Boothby 1984; Donnenfeld 1986; Elliott 1986) reported the outcome of allergic reactions but there were no events (very low‐quality evidence). See Analysis 1.6.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intravenous (IV) versus irrigation, Outcome 6 Adverse events (maternal).

Maternal length of hospital stay

Four of the studies (Elliott 1986; Gonen 1986; Lavery 1986; Saravolatz 1985) provided data for this outcome and there was no clear difference between the intravenous antibiotics and antibiotic irrigation groups (average mean difference (MD) 0.28 days, 95% CI ‐0.22 to 0.79 days, (random‐effects analysis), P = 0.27, 512 women) (Heterogeneity: Tau² = 0.11; Chi² = 5.34, df = 3 (P = 0.15); I² = 44%). See Analysis 1.7.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intravenous (IV) versus irrigation, Outcome 7 Maternal length of hospital stay (days).

Readmissions

This outcome was not reported by any of the studies in this comparison.

Infant

The included studies did not report on any of this review's infant secondary outcomes.

Oral thrush

Infant length of hospital stay

Immediate adverse effects of antibiotics on the infant.

Comparison 2: Intravenous antibiotics versus oral antibiotics (one study, 80 women)

One study compared intravenous antibiotics versus oral antibiotics (Voto 1986), but did not report on any of this review's primary or secondary outcomes. The study enrolled 80 women and compared intravenous cefoxitin (2 g administered through an intravenous drip immediately after the umbilical cord had been cut; thereafter, two doses, 2 g each dose, were administered at four and eight hours after the first dose) versus oral ampicillin (2 g/day taken four times over seven days). Only 53 women were analysed due to errors in collection of the samples for culture. The study reported the results of cultures of the wound, urine, endocervix and uterine incision.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We included 10 studies that compared different routes of administering prophylactic antibiotics: intravenous versus irrigation (nine studies) and intravenous versus oral (one study).

The main findings indicate that there is no difference between intraoperative irrigation of the uterus and intravenous prophylactic antibiotics in reducing the risk of post‐caesarean endometritis, as shown in Table 1. However, this is based on low‐quality evidence due to study design limitations and imprecision. The results for all other reported outcomes: wound infection, urinary tract infection, serious infectious complications, postpartum febrile morbidity, maternal allergic reactions and maternal length of hospital stay, are based on a very low‐quality evidence. We downgraded the quality of evidence for limitations of study design and for imprecision. Studies included relatively few patients and few events and have wide 95% confidence intervals that include both appreciable benefit and appreciable harm, as shown in Table 1. It is notable that we could not find any study that has measured or reported neonatal or infant outcomes.

This summary of our main results underscores the outstanding uncertainties regarding the effectiveness of different routes of prophylactic antibiotics in preventing post‐caesarean infections.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

In current practice, evidence regarding antibiotic prophylaxis is based on high‐quality studies comparing intravenous antibiotics with placebo or no therapy. Prior to conducting and reporting our review, there was no synthesised evidence comparing different routes of antibiotic prophylaxis for preventing infection after caesarean section. With this in mind, we conducted this review. Several randomised controlled trials (RCTs) included in our review did not compare the outcome data between different routes of antibiotic administration. Furthermore, one of our pre‐specified primary outcomes, infant sepsis, was not measured or reported by any of the studies. Irrigation with antibiotics was compared with intravenous antibiotics in nine trials. We found only one RCT trial involving 80 women comparing another route of antibiotic prophylaxis (oral) versus intravenous antibiotics, however it did not report on any of this review's primary or secondary outcomes.

Quality of the evidence

All studies included in this review were categorised as having an ’unclear’ risk of bias for allocation concealment and six of the 10 included studies were categorised as having an 'unclear' risk of bias for random sequence generation. Therefore caution is advised when interpreting the results. Furthermore, the total number of all women enrolled was 1354 in 10 studies. Most of the included studies were underpowered for the primary outcomes and for adverse events.

For the main comparison of intravenous antibiotics versus antibiotic irrigation, the quality of evidence was low for endometritis (Table 1). This provides some indication of the likely effect. However, the likelihood that it will be substantially different (a large enough difference that it might have an effect on a decision) is high. The quality of evidence was very low for all other outcomes including wound infection, urinary tract infection, postpartum febrile morbidity, serious infectious complications, and maternal allergic reactions (Table 1). This does not provide a reliable indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different is very high.

The quality of the evidence was very low to low. The main reasons for downgrading the evidence included study design limitations and imprecision.

Potential biases in the review process

We used rigorous steps to eliminate bias during conducting and reporting our review. However, it is possible that trials may have been overlooked. Furthermore, we have explicitly indicated that some outcomes were not reported and we could not obtain data regarding the unreported points in methods and outcomes by directly contacting the trial investigators.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The recently published World Health Organization (WHO) evidence‐based guidance for preventing peripartum infections recommended routine antibiotic prophylaxis for women undergoing elective or emergency caesarean section (WHO 2015). For caesarean section, prophylactic antibiotics should be given prior to skin incision, rather than intraoperatively after umbilical cord clamping. For antibiotic prophylaxis for caesarean section, a single dose of first‐generation cephalosporin or penicillin should be used in preference to other classes of antibiotics. The WHO guideline development group added in a remark that the intravenous route should be used for antibiotic administration given that the evidence underpinning this recommendation was based on findings from trials where the majority used this route (WHO 2015). This clearly shows there are insufficient head‐to‐head comparisons between different routes to formulate a direct recommendation.

To our knowledge this is the first systematic review assessing the benefits and harms of different routes of antibiotic administration for prevention of infection after caesarean section. We have noted that it was only in 1980 when a preliminary report (Long 1980) described the use of Intrauterine irrigation with cefamandole nafate in reducing the incidence of endometritis after caesarean section. The technique of irrigation was later replicated by the randomised controlled trials included in this review.

Regarding the different routes of prophylactic antibiotics, the majority of the studies compared intravenous administration with the peritoneal and uterine lavage. One excluded trial considered the intravenous route the most effective means (Conover 1984), another trial considered the intrauterine antibiotic lavage more safe and cost‐effective than intravenous route (Donnenfeld 1986), whereas (Gonen 1986) could not find a difference in benefits and harms.

It is noteworthy that, in agreement with our observation, two Cochrane systematic reviews on antibiotic prophylaxis versus no prophylaxis for preventing infection after caesarean section (Smaill 2014) and on the different classes of antibiotics for preventing infection at caesarean section (Gyte 2014), also reported that there was incomplete information collected about the potential adverse effects, especially on the baby, further complicating the assessment of overall benefits and harms of prophylactic antibiotics given for prevention of infection at caesarean section.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There was a low‐quality evidence of no difference between irrigation and intravenous administration of antibiotic prophylaxis in reducing the risk of endometritis after caesarean section. For other outcomes, there is insufficient evidence regarding which route of administration of prophylactic antibiotics is most effective at preventing post‐caesarean infections.

Implications for research.

Having reviewed studies addressing an issue as important as comparing the different routes of administration of antibiotic prophylaxis for the most commonly practised obstetric major surgery, the number of high quality randomised controlled trials (RCTs) attempting to answer this clinical question was small. Furthermore, methodological flaws in designing, conducting and reporting the few available studies, affected the quality of evidence extracted from the included studies. This calls for investigators to work on improving the methodological infrastructure of future attempted RCTs. The latest included study in this review dates back to 1990, and obviously, over more than quarter of a century, novel antibiotics, available through more varied routes, have been introduced into clinical practice. Hence, clinicians should embark on putting those newer agents into clinical trials, comparing their efficacies and safety profiles.

Additionally, not all available routes of antibiotic administration have been included in the reviewed studies. Trans‐rectal administration, for example, has not been studied. It might prove to be of value, especially considering the gastro‐intestinal upset surrounding caesarean delivery. The intravenous route is the standard route of prophylactic antibiotic administration, but more studies are needed to evaluate the uterine lavage route, which showed comparable effect and seems more suitable for emergency caesarean section; and the oral route as it has not been thoroughly examined, although it is very simple, convenient and suitable for women who receive regional anaesthesia. Future research should evaluate the most effective and safe route of administration to inform policy‐making.

Lastly, the possible neonatal effects of maternal administration of antibiotics were not reported in any of the included studies. Such effects might include change of neonatal infection rates, possible side effects of drugs, potentially causing neonatal jaundice, or drug reactions.

We, therefore, suggest that well‐designed, properly‐conducted, and clearly‐reported RCT's be considered a research priority for investigators in the field of childbirth. Such studies should evaluate the more recently available antibiotics, elaborating on the various available routes of administration, and exploring potential neonatal side effects of such interventions.

Notes

Alfirevic 2010 describes plans for that review to be separated into three reviews and a further two reviews prepared in order to provide comprehensive coverage of the review topic. These five reviews are listed below.

Different classes of antibiotics given to women routinely for preventing infection after caesarean section (Gyte 2014).

Different regimens of penicillin antibiotic given to women routinely for preventing infection after caesarean section (Liu 2014).

Different regimens of cephalosporin antibiotic given to women routinely for preventing infection after caesarean section (protocol in preparation).

Timing of prophylactic antibiotics for preventing infectious morbidity in women undergoing caesarean section (Mackeen 2014).

Routes of administration of antibiotic prophylaxis for preventing infection after caesarean section (this review).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the valuable input of Lynn Hampson in the development of the search strategy. We would also like to thank all members of the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group Editorial base at the University of Liverpool, UK, led by Frances Kellie, for their kind assistance with preparation of the protocol.

As part of the pre‐publication editorial process, this review has been commented on by two peers (an editor and referee who is external to the editorial team), a member of the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's international panel of consumers and the Group's Statistical Adviser.

This project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research, via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search terms

(cesarean OR caesarean OR caesarian OR cesarian) AND (antibio*)

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Intravenous (IV) versus irrigation.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Endometritis | 8 | 966 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.70, 1.29] |

| 1.1 Single IV dose | 2 | 268 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.17 [0.59, 2.32] |

| 1.2 Multiple IV doses | 6 | 698 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.64, 1.26] |

| 2 Wound infection | 7 | 859 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.49 [0.17, 1.43] |

| 2.1 Single IV dose | 2 | 264 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.25 [0.03, 2.20] |

| 2.2 Multiple IV doses | 5 | 595 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.19, 2.28] |

| 3 Postpartum febrile morbidity | 3 | 264 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.48, 1.60] |

| 4 Urinary tract infection | 5 | 660 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.25, 2.15] |

| 5 Serious infectious complication | 1 | 81 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6 Adverse events (maternal) | 3 | 284 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6.1 Allergic reactions | 3 | 284 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7 Maternal length of hospital stay (days) | 4 | 512 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.28 [‐0.22, 0.79] |

Comparison 2. Intravenous versus irrigation: sensitivity analysis.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Endometritis | 5 | 574 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.62, 1.23] |

| 2 Wound infection | 4 | 467 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.42 [0.11, 1.61] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Berkeley 1990.

| Methods | Parallel randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: women in labour, with or without ruptured membranes. Exclusion criteria: participants < 18 years of age, had a known allergy to penicillin or cephalosporin antibiotics, had received other antibiotics in the 72 hours prior to admission, required prophylactic antibiotics for medical indications, had received steroid therapy for either underlying medical illness or enhancement of fetal lung maturity, had severe renal or hepatic dysfunction, or had clinical evidence of chorioamnionitis at the time of caesarean section. |

|

| Interventions | Number of women randomised: 107. Trial arm 1: 53 women were randomised to 2 g of cefotaxime in 1000 mL of normal saline through uterine lavage. Trial arm 2: 54 women were randomised to 1 g of cefotaxime intravenously at the time of cord clamping followed by a dose of 1 g 6 and 12 hours after the initial dose. The investigators added a third group to establish a baseline postoperative infection rate in their facility. The first 50 women in calendar year 1982 who underwent caesarean section in labour and did not receive prophylactic antibiotics by any method were evaluated by chart review using the same criteria as those used in the trial. |

|

| Outcomes | Febrile morbidity. Endomyometritis. | |

| Notes | Centre: Department of obstetrics and gynaecology, New York Hospital, Cornell Medical Center. Country: USA. Language: English. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | A computer‐generated randomisation code supplied by the sponsor. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement of ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk’. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Given that the control arm was easily distinguished from the treatment arm during treatment, participants and personnel were not blinded. We judge that the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | The trial was not blinded. We judge that the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Incomplete outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons (protocol violations) across groups. 107 participants who signed consent forms at the time of admission to the obstetric service ultimately underwent caesarean section in labour. 7 participants were excluded; 3 received steroid therapy for induction of fetal lung maturity, 1 had no chart available for subsequent review, 1 did not undergo the lavage to which she was randomised, and 2, both in the intravenous group, had protocol violations related to errors in the administration of the second and third prophylactic doses. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | The study protocol is not available and the study report fails to include results for a key outcome that would be expected to have been reported for such a study. |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other sources of bias. |

Boothby 1984.

| Methods | Parallel randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | All women who underwent primary caesarean section at University Hospital during the 6‐month study period were included. Exclusion criteria: women were excluded if they had a history of penicillin or cephalosporin allergy or a known infectious process or had recently used antibiotics. |

|

| Interventions | Number of women randomised: 103. Trial arm 1: 53 women were randomised to intraoperative irrigation with a cefoxitin solution. The antibiotic irrigation solution contained 2 g of cefoxitin dissolved in 1 L of normal saline. After delivery of the Infant, placenta and membranes, the open uterus, wound margins and endometrial cavity were irrigated with a bulb syringe, creating a jet‐like action on the tissues. The closed uterine incision was then irrigated. Both gutters were irrigated and cleared of any blood clots. After closure of the peritoneum the wound was irrigated, and a final irrigation was performed in the subcutaneous tissue after closure of the fascia. Approximately 200 mL of solution was used during each irrigation step. Trial arm 2: 50 women were randomised to intravenous prophylaxis with cefoxitin and saline irrigation. Women receiving intravenous prophylaxis were given 2 g of cefoxitin after cord clamping by the anaesthesiologist or nurse‐anaesthetist and then 2 g at 6, 12 and 18 hours after surgery. |

|

| Outcomes | Febrile morbidity. Postpartum endometritis. Urinary tract infection. Wound infection. Drug allergy. |

|

| Notes | Centre: Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University Hospital of Jacksonville. Country: USA. Language: English. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Using a randomisation table. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement of ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk’. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Given that the control arm was easily distinguished from the treatment arm during treatment, participants and personnel were not blinded. We judge that the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | The study was not blinded. We judge that the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement of ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk’. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | The study protocol is not available. There is insufficient information to permit judgement of ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk’. |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other sources of bias. |

Donnenfeld 1986.

| Methods | Parallel randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | The study enrolled 103 women. All women in the clinic who were in labour immediately prior to caesarean section were entered into the study. Exclusion criteria: known penicillin or cephalosporin allergies, those taking antibiotics, those requiring prophylaxis against bacterial endocarditis and those with ongoing infections. |

|

| Interventions | Number of women randomised: 103. Trial arm 1: 53 women were randomised to 1 g intravenous cefazolin solution immediately after cord clamping, followed by 2 subsequent doses given at 8‐hour intervals. Trial arm 2: 50 women were randomised to an intrauterine lavage of 1 g cefazolin in 500 mL normal saline. A bulb syringe was used to administer 300 mL directly into the uterine cavity as well as to thoroughly irrigate the margins of the entire uterine incision, creating a jet‐like effect. After closure of the uterus, 100 mL was used for lavage of the vesicouterine peritoneum. The final 100 mL was used to irrigate the subcutaneous adipose tissue. The excess run‐off of irrigant was suctioned at the time of application. |

|

| Outcomes | Endometritis. Postpartum hospital stay. |

|

| Notes | Centre: Section on perinatology, Department of Obsterics and Gynecology, Pennsylvania Hospital. Country: USA. Language: English. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement of ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk’. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement of ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk’. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Given that the control arm was easily distinguished from the treatment arm during treatment, participants and personnel were not blinded. We judge that the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | The study was not blinded. We judge that the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Incomplete outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for incomplete data across groups. 2 women were excluded due to administration of the intravenous antibiotic at improper intervals. 1 woman was excluded due to deviation from the intrauterine lavage protocol at the time of surgery. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | The study protocol is not available and study report fails to include results for a key outcome that would be expected to have been reported for such a study. |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other sources of bias. |

Elliott 1986.

| Methods | Multi‐arm randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | The study included 158 women who were to be delivered by caesarean section and who were in active labour or had ruptured membranes and had at least 1 digital vaginal examination. Criteria for exclusion from the study included: any known allergy to cephalosporins or penicillin, the presence of a fever greater than or equal to 37.8o C during labour with suspicion of chorioamnionitis, or maternal use of any antibiotic during the 2‐week period before delivery. | |

| Interventions | Number of women randomised: 158. Trial arm 1: 39 women, a control group that received no prophylactic antibiotic therapy. Trial arm 2: 39 women were randomised to 2 g of cefoxitin by intravenous injection over a 3‐ to 5‐minute period after the fetal umbilical cord was clamped. 7 additional doses of 2 g of cefoxitin were administered every 6 hours for a 2‐day course of therapy. Trial arm 3: 42 women were randomised to uterine and peritoneal lavage with 2 g of cefoxitin in 1 L of normal saline. After delivery of the placenta, the fundus of the uterus was irrigated with approximately 300 mL of antibiotic solution, the uterine incision was irrigated with 150 mL, after closure of the first layer 150 mL, and bladder flap 150 mL, then the remainder was used to irrigate the peritoneal cavity. Any remaining irrigating solution was suctioned from the peritoneal cavity before closing the abdomen. No further antibiotic therapy was administered. Trial arm 4: 38 women were randomised to irrigation plus intravenous treatment. This group was given antibiotics as described for both group 2 and group 3. |

|

| Outcomes | Endomyometritis.

Urinary tract infection.

Wound infection.

Pulmonary infection.

Septicemia. Total febrile morbidity. Seroma. Transfusion reaction. Atelectasis. Fever index (degree‐h). Hospital stay (d). |

|

| Notes | Centres: Letterman Army Medical Center and Womack Army Community Hospital under a protocol approved by the hospital Research and Human Use Committees. Country: USA. Language: English. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation into 1 of 4 treatment groups was performed by using a table of random numbers. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement of ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk’. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. The investigators indicated that the intravenous antibiotic protocols involved 2 days of therapy due to the investigators' impression that the incidence of subclinical infection is high and a treatment course of antibiotics is appropriate. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement of ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk’. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | The study protocol is not available. There is insufficient information to permit judgement of ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk’. |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other sources of bias. |

Gonen 1986.

| Methods | Parallel randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | The study included 217 women who underwent caesarean section. Exclusion criteria: fever or other infection during labour, using antibiotics within 48 hours, a separate indication for using prophylactic antibiotics, allergy to penicillin or cephalosporin. |

|

| Interventions | Number of women randomised: 217. Trial arm 1: 107 women were randomised to intravenous cefamandole 6 vials of 1 g cefamandole. First dose given after cord clamping, followed by 5 doses 6 hours apart. Trial arm 2: 110 women were randomised to irrigation with 2 g cefamandole in 1000 mL normal saline. The uterine cavity and incision irrigated by 300 mL, 150 after closure of the first layer, and 150 for the bladder flap, gutters and subcutaneous layer. |

|

| Outcomes | Endometritis.

Wound infection.