Abstract

Introduction

Lung ultrasound (LUS) is expanding from the field of emergency medicine, also to the pneumological specialist field, becoming part of the diagnostic procedure of lung consolidation.

Case presentation

A 78-year-old male was admitted to our emergency department for exertional dyspnea. LUS was performed, thus showing at right hemitorax air interface, A lines pattern, pleural sliding abolished on the whole hemitorax, thus suggesting a pneumothorax, but no evidence of lung point. A scan of lower lung segment showed an absence of the diaphragmatic excursion, suggestive for hemiparalysis of the diaphragm muscle, then confirmed by a subcostal scan. Moreover, at the lower segment of right hemitorax there was mild pleural effusion allowing the visualization of a round-shaped parenchymal consolidation with the absence of air bronchograms.

Conclusions

LUS allowed the visualization of a particular and rare disease such as anthracosis-associated rounded atelectasis, thus leading to a more correct and faster patient management.

Keywords: Ultrasound, Lung, Anthracosis, Atelectasis

Introduction

Rounded atelectasis is a rare peripheral alveolar collapse arising from several pleural diseases [1, 2]. Rounded atelectasis is more common in men (80%) than in women, and it is due to occupational exposure to mineral dusts [1]. Less frequently rounded atelectasis is related to exudative pleuritis, or pulmonary diseases affecting pleura, such as legionellosis and sarcoidosis [1]. Despite a clear radiological presentation, rounded atelectasis is often asymptomatic and sometimes patients may complain of chest pains, dyspnoea or cough [1, 2].

Case presentation

A 78-year-old male was admitted to our emergency department for exertional dyspnea. His past history was characterized by tobacco consumption, ascending aortic ectasia, moderate-severe aortic valve regurgitation, mild mitral valve regurgitation, cholecystectomy for calculosis. At physical examination there was hypoventilation of right hemitorax, upper airways were pervious, respiratory rate was 20 breaths /min, and oxygen saturation was 89%. A blood gas analysis was performed, showing a slight hypoxemic normocapnic respiratory failure.

Lung ultrasound (LUS) was performed with patient in supine position, thus showing at right hemithorax–air interface, A lines pattern, pleural sliding abolished on the whole hemithorax, and no evidence of lung point; B lines were not evident. A scan of lower lung segment showed an absence of the diaphragm excursion, suggestive for hemiparalysis of the diaphragm muscle, then confirmed by a subcostal scan (Figs. 1, 2). Moreover, at the lower segment of right hemitorax there was mild pleural effusion allowing the visualization of a round-shaped parenchymal consolidation with the absence of air bronchograms and the presence of fluid bronchograms (Fig. 3). At the Color Doppler ultrasound analysis, arterial vascularization was present (Fig. 4). Otherwise, left hemitorax was physiological with air interface, A lines pattern, and pleural sliding was present.

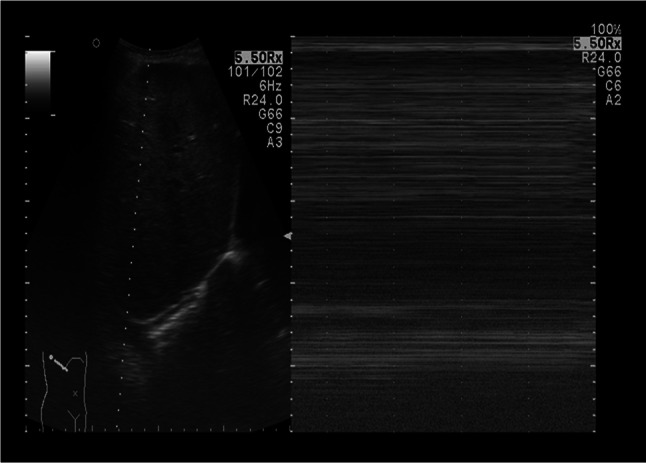

Fig. 1.

Right parasternal scan to supine patient: the M-mode modality shows the absence of pleural sliding (stratosphere or barcode sign)

Fig. 2.

Subcostal scan at mid-axillary level: the M-mode shows no movement of right hemidiaphragm; in B-mode curtain sign was absent.

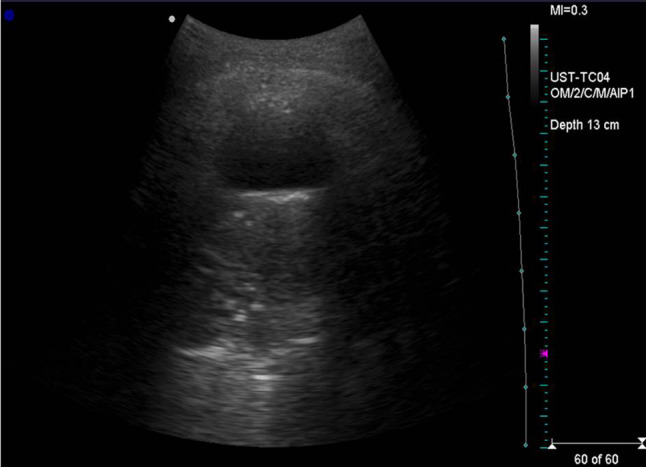

Fig. 3.

A small pleural effusion allows the visualization of lower lung parenchyma. Lung is consolidated, showing no air bronchograms

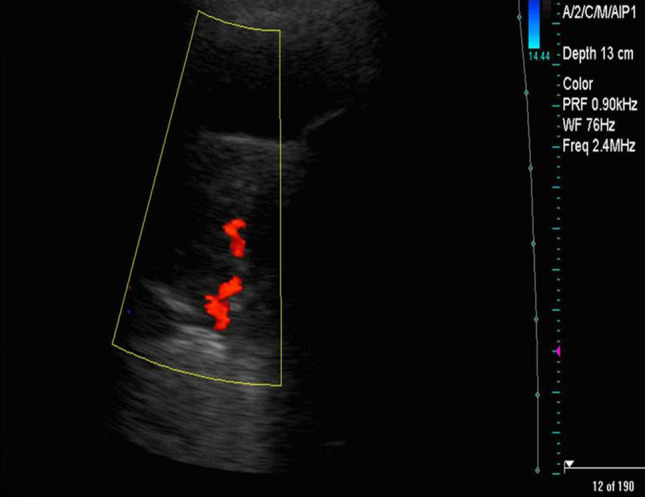

Fig. 4.

Color Doppler analysis on consolidated lung: an arterious colordoppler sign has been revealed

Following these ultrasound findings, patient performed a chest computed tomography (CT) demonstrating the following: "on the right, minimum basal pleural effusion is present; at the lower segment of the right lung, a consolidating area of roundish shape, compatible with round atelectasis, is appreciated. The atelectatic area is characterized by peripherally ribbons thickening with prevalent fibrotic-retracting aspects and grouping of vessels and bronchi converging towards consolidation itself. The left lung shows no parenchymal alterations or pleural reactive signs (Fig. 5); there is reduced expansion of the right lung, and ipsilateral mediastinal dislocation (Fig. 6)”. Subsequently, patient performed a computed tomography (CT)-guided transcutaneous biopsy highlighting a diagnosis of anthracosis.

Fig. 5.

HRCT imaging: at the lower segment of the right lung, a consolidating area of roundish shape, compatible with round atelectasis is appreciated

Fig. 6.

Scanogram: there is reduced expansion of the right lung, and ipsilateral mediastinal dislocation due to attracting phenomena

Discussion

According to LUS protocols, lack of lung sliding is typically referred as sign of pneumothorax, especially in traumatic patients, but with low specificity [3],it is required the visualization of lung point or the evidence with a second-level method for pneumothorax (PNX) definitive diagnosis. Indeed, reduced or abolished lung sliding can be sign of other diseases, such as primary alterations of the pleura or atelectasis, which must be considered for differential diagnosis. In our case, the sonographic research of the lung point was negative. The “solution” for this finding was the highlighting by ultrasound of an immobility of the right lung segments, suggestive of a chest pump failure, caused by anthracosis disease.

In the right lung lower segment there was evidence of a mild pleural effusion which allowed the visualization of a round-shaped parenchymal consolidation without evidence of static or dynamic aerial bronchograms. An inward arterial vascularization was found at duplex ultrasound analysis. These findings were suggestive of atelectasis disease, later confirmed at chest CT. In particular, rounded atelectasis represents a specific peripheral alveolar collapse [1, 2]. Pleural effusion can induce local atelectasis by exerting a pressure on the nearest lung. When fluid amount overcomes the absorption of adjacent alveoli, visceral pleura can be fissured, thus inducing the translocation of the lung towards that fissure. Therefore, the lung folds in a concentric shape maintained by developing adhesions. When the effusion is resorbed, the lung fills in the space around rounded atelectasis. Otherwise, the lesions can be induced by local pleuritis due to irritant agents that can lead to shrinkage and thickening of pleura and thus of the adjacent lung [4, 5].

Therefore, anthracosis-related abolished lung sliding can be considered as a new “false positive” case of pneumothorax, to differentiate from other false positive cases such as fibrothorax, panlobular emphysema, severe fibrosis with honeycombing and traction cysts, pleural adhesion, loculated pleural effusions, obstructive atelectasis, abscesses, empyema, atelectasis, cysts, blebs, lung contusions, tumors infiltrating the chest wall and all the other conditions which can reduce lung and pleura mobility, including medical procedures like tube thoracostomy, intubation or insertion of a chest tube [6, 7].

Although chest X-ray is the first step in imaging for a suspected respiratory pathology, in our case LUS performed at bed-side by clinician to complete the medical history and examination has led to changing the prescription from chest X-ray to CT, due to several and particular pathological findings on examination, towards which chest x-ray has shown a poor specificity [8–14]. Especially in the field of acute care and, therefore, in the emergency medicine, bed-side ultrasound utilization to complete the physical examination is increasingly used [15–19]. Several works have shown how completing the traditional physical examination with a point of care ultrasound improves the medical's decision making, shortening hospitalization times, saving unnecessary exams [15–20], also leading to a better and more correct therapy for the patient [9, 21, 22]. This concept is particularly true in poorly mobilizable patients where ultrasound can be applied immediately and in a simple manner, and in the pediatric field with radiation savings [11, 23–25].

In conclusion, LUS allowed the visualization of a particular and rare disease such as anthracosis-induced rounded atelectasis, thus leading to a more correct and faster patient management. Although LUS did not lead to an etiological diagnosis of the area of atelectasis, in the clinical context it allowed to reach a diagnostic conclusion different from the PNX (incorrect), and to set a correct therapeutic diagnostic iter which led to the diagnosis of anthracosis. Our clinical case demonstrates how LUS is expanding from the field of emergency medicine, also to the specialist pneumological field, becoming part of the diagnostic procedure of lung consolidation and atelectasis.

Acknowledgements

Noemi Dell’Orso for editorial assistance.

Abbreviations

- LUS

Lung ultrasound

- CT

Computed tomography

- PNX

Pneumothorax

Funding

None (for all authors).

Data availability

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article (and its additional file).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Available with author. Written informed consent to participate was obtained.

Informed consent

We confirm that we have obtained written consent to publish from the participant to report individual patient data.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

A. Boccatonda, Email: andrea.boccatonda@gmail.com

G. Primomo, Email: g.primomo@gmail.com

G. Cocco, Email: cocco.giulio@gmail.com

D. D’Ardes, Email: damiano.med@libero.it

S. Marinari, Email: pneumologia.chieti@asl2abruzzo.it

M. Montanari, Email: montanarimarco99@gmail.com

F. Giostra, Email: fabrizio.giostra@sanita.marche.it

C. Schiavone, Email: c.schiavone@unich.it

References

- 1.Stathopoulos GT, Karamessini MT, Sotiriadi AE, et al. Rounded atelectasis of the lung. Respir Med. 2005;99:615–623. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Partap VA. The comet tail sign. Radiology. 1999;213:553–554. doi: 10.1148/radiology.213.2.r99nv08553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lichtenstein DA, Menu Y. A bedside ultrasound sign ruling out pneumothorax in the critically ill. Lung sliding. Chest. 1995;108(5):1345–1348. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.5.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woodring JH. Pleural effusion is a cause of round atelectasis of the lung. J Ky Med Assoc. 2000;98:527–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Younis WG, Dernaika TA, Jones KR, Kinasewitz GT, Keddissi JI, et al. Rounded atelectasis with atypical computed tomography findings. Respir Care. 2006;51(7):761–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aspler A, Stone MB. Pitfalls in the ultrasound diagnosis of pneumothorax: the authors respond. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(9):1127. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaetano R, D'Amato M, Ghittoni G. Questioning the ultrasound diagnosis of pneumothorax. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(11):1426–1427. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tierney DM, Huelster JS, Overgaard JD, Plunkett MB, Boland LL, St Hill CA, et al. Comparative performance of pulmonary ultrasound, chest radiograph, and CT among patients with acute respiratory failure. Crit Care Med. 2019 doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soldati G, Demi M, Smargiassi A, Inchingolo R, Demi L. The role of ultrasound lung artifacts in the diagnosis of respiratory diseases. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2019;13(2):163–172. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2019.1565997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mojoli F, Bouhemad B, Mongodi S, Lichtenstein D. Lung ultrasound for critically Ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(6):701–714. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201802-0236CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guglielmo N. Lung ultrasound in diagnosing pneumonia in childhood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Ultrasound. 2018;21(3):183–195. doi: 10.1007/s40477-018-0306-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cocco G, Boccatonda A, D'Ardes D, Galletti S, Schiavone C. Mantle cell lymphoma: from ultrasound examination to histological diagnosis. J Ultrasound. 2018;21(4):339–342. doi: 10.1007/s40477-018-0318-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ianniello S, Piccolo CL, Trinci M, Cat CA, Miele V. Extended-FAST plus MDCT in pneumothorax diagnosis of major trauma: time to revisit ATLS imaging approach? J Ultrasound. 2019;22(4):461–469. doi: 10.1007/s40477-019-00410-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boccatonda A, Decorato V, Cocco G, Marinari S, Schiavone C. Ultrasound evaluation of diaphragmatic mobility in patients with idiopathic lung fibrosis: a pilot study. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2018;14:1. doi: 10.1186/s40248-018-0159-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soldati G, Demi M. The use of lung ultrasound images for the differential diagnosis of pulmonary and cardiac interstitial pathology. J Ultrasound. 2017;20(2):91–96. doi: 10.1007/s40477-017-0244-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blanco P, Ferreyra A, Badie P, Carabante S. Severe massive pulmonary thromboembolism: a case reinforcing the crucial role of point-of-care ultrasound in emergency settings. J Ultrasound. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s40477-019-00417-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cocco G, Ricci V, Boccatonda A, Iannetti G, Schiavone C. Migration of calcium deposit over the biceps brachii muscle, a rare complication of calcific tendinopathy: ultrasound image and treatment. J Ultrasound. 2018;21(4):351–354. doi: 10.1007/s40477-018-0336-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fusco P, Cofini V, Di Carlo S, Luciani A, Scimia P, Petrucci E, Behr AU, Necozione S, Colantonio LB, Fiore G, Vergallo A, Marinangeli F. Ultrasonography and Italian anesthesiology: a national cross-sectional study. J Ultrasound. 2019;22(1):77–83. doi: 10.1007/s40477-018-0334-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piccolo CL, Trinci M, Pinto A, Brunese L, Miele V. Role of contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) in the diagnosis and management of traumatic splenic injuries. J Ultrasound. 2018;21(4):315–327. doi: 10.1007/s40477-018-0327-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sperandeo M, Frongillo E, Dimitri LMC, Simeone A, De Cosmo S, Taurchini M, Cipriani C. Video-assisted thoracic surgery ultrasound (VATS-US) in the evaluation of subpleural disease: preliminary report of a systematic study. J Ultrasound. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s40477-019-00374-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boccatonda A, D'Ardes D, Cocco G, Cipollone F, Schiavone C. Ultrasound and hepatic abscess: a successful alliance for the internist. Eur J Intern Med. 2019;68:e19–e21. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2019.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boccatonda A, Groff P. High-flow nasal cannula oxygenation utilization in respiratory failure. Eur J Intern Med. 2019;64:10–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2019.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rea G, Sperandeo M, Di Serafino M, Vallone G, Tomà P. Neonatal and pediatric thoracic ultrasonography. J Ultrasound. 2019;22(2):121–130. doi: 10.1007/s40477-019-00357-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merli L, Nanni L, Curatola A, Pellegrino M, De Santis M, Silvaroli S, Paradiso FV, Buonsenso D. Congenital lung malformations: a novel application for lung ultrasound? J Ultrasound. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s40477-019-00406-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sperandeo M, Frongillo E, De Cosmo S, Cipriani C. Transthoracic ultrasound in children. J Ultrasound. 2018;21(4):355–356. doi: 10.1007/s40477-018-0339-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article (and its additional file).