Abstract

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia is the most frequent cancer in children: it represents 80% of leukemias and about 24% of all neoplasms diagnosed between 0 and 14 years. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia mainly affects children between 2 and 5 years old and in this age group the incidence is about 80–90 cases per million per year. In acute lymphoblastic leukemia, cancer cells multiply rapidly and accumulate in the bone marrow and subsequently invade the blood. However, at the time of diagnosis, leukemia rarely occurs outside the bone marrow or blood vessels and the extramedullary involvement happens mostly in patients with refractory or relapsing disease. In this article, we report an unusual clinical presentation of acute B cell lymphoblastic leukemia with intestinal and ovarian localizations in a 5-year-old girl.

Keywords: Pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Intestinal invagination, Ovarian tumor, Ultrasound, Computed tomography

Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common childhood malignancy. In Italy the ALL represents 80% of leukemias and 24% of all cancers diagnosed between 0 and 14 years [1]. The incidence is 30 cases per year per million subjects aged 0–17 years, while the peak incidence is between 2 and 5 years of age; in this age group, the ALL affects about 80–90 children per million per year and is slightly more frequent in boys than in girls [1–3]. ALL is a rapidly progressive blood cancer caused by the neoplastic transformation of cells of the lymphoid lineage with uncontrolled multiplication and consequent accumulation of immature B or T lymphocytes (lymphoblasts) in the hematopoietic bone marrow and peripheral blood [3, 4]. The ALL can be localized into internal organs, thus mimicking a solid tumor and in this case it is called "extramedullary leukemia" [4]. At the time of diagnosis, the main targets of extramedullary leukemia are the lymph nodes, spleen and liver [3]. The mediastinum, the central nervous system (CNS), the testes, the ovaries and the eye are rarely affected by the disease; moreover, intestinal, skin, skeletal, lung, parotid and cardiac localizations are exceptional and the involvement of the extramedullary organs occurs mostly in patients with refractory or relapsing disease [3, 4]. In this article, we describe an unusual onset of B cell ALL (B-ALL) in a 5-year-old girl who came to our observation because of abdominal pain.

Case report

In March 2019, a 5-year-old girl went to the emergency room of our hospital due to widespread and persistent abdominal pain for 3 days. The little girl underwent blood tests which showed only an increase in ESR (87 mm/h) and CRP (6.60 mg/L). In addition, the girl received chest X-ray, direct X-ray examination of the abdomen and ultrasound of the abdomen and pelvis. Chest X-ray was normal. X-ray of the abdomen, performed in the standing position, revealed distended intestinal loops with air–fluid levels in the left hypochondrium/flank and poor representation of meteorism in the rectum, in the absence of free air (Fig. 1). The abdominal ultrasound showed in the left flank and mesogastrium a "mass" with the characteristics of the intestinal invagination, ileo-ileal type (Fig. 2). The invaginated loop showed a focal thickening of the wall that appeared remarkably hypoechoic and extremely vascularized on color Doppler examination (Fig. 3). The pelvic ultrasound showed the right ovary increased in size due to the presence of a large lesion with inhomogeneous hypoechoic echostructure and with some vascular poles on color Doppler. A small amount of fluid in the pouch of Douglas was visible (Fig. 4). The little girl was hospitalized in the emergency surgery department and was submitted to videolaparoscopic surgery. Laparoscopy identified a jejunal intestinal segment infiltrated by a partially occlusive solid formation of size 2 cm; intestinal tract resection including lesion and end-to-end anastomosis and biopsy of the enlarged right ovary were effectuated. The microscopic histological examination of the intestinal lesion revealed a widespread proliferation of atypical lymphoid cells that infiltrated the full thickness of the intestinal wall. The cells were medium in size with poor cytoplasm and roundish or irregular nucleus, often vesicular and nucleolate; moreover, there was a high rate of mitosis and apoptosis. Immunohistochemical study showed that the tumor cells were positive for TdT (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase), CD45, CD10, PAX-5, and CD79a (Fig. 5). Microscopic histological examination of the biopsy sample of the right ovary showed a flap of cortical infiltrated by atypical lymphoid cells with the same characteristics as those of the intestinal lesion (Fig. 6). The histological findings were indicative of lymphoproliferative disorder compatible with B-ALL/B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma (B-LBL) and, therefore, the little girl was admitted to the oncohematology department. Blood tests were performed again which showed reduction of the inflammation indexes, although an increase in ESR (ESR 46 mm/h, CRP 2.30 mg/L) persisted and normal level of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH 573 U/L). Complete blood count (CBC) showed only a mild microcytic hypochromic anemia (Hb: 10.20 g/dL, HCT: 32.40%, MCV: 72.50 fl, MCH: 23.50 pg). The microscopic examination of the peripheral blood smear showed erythrocyte anisocytosis, rare immature leukocytes and platelet aggregates, while flow cytometry highlighted a small percentage (2%) of lymphoid elements with phenotype CD45dim, CD19, CD10 and CD58. Therefore, on the basis of these results, bone marrow blood was analyzed and taken by means of needle aspiration, which found 66% of blasts with typical immunophenotype of the B-III (pre-B) ALL, according to the EGIL classification (European Group for the Immunological Characterization of Leukemias). Furthermore, the cytogenetic analysis by RT-PCR (reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction) of the bone marrow blood sample revealed cells with E2A/PBX1 hybrid gene due to the translocation t (1.19); the karyotype was diploid (46, XX) with DNA index = 1. Once the diagnosis was established, to carry out correct staging of the disease, further diagnostic investigations were performed including the examination of the cephalorachid fluid, which did not show atypical cells, and radiological examinations. The little girl underwent skeleton X-ray, ultrasound of the superficial and deep lymph nodes, of the abdomen and pelvis and whole body computed tomography (CT). The radiographs of the entire skeleton did not show bone lesions, and the ultrasound did not detect superficial and deep lymphadenopathies, hepatosplenomegaly and lesions of the organs of the upper abdomen, while in pelvis the large right ovarian formation and small amount of fluid in pouch of Douglas were visible. The CT examination, performed after intravenous administration of contrast medium (CM), of the brain, neck, chest and upper abdomen did not find any anomalies, while in the pelvis the free fluid and the enlarged right ovary with finely inhomogeneous density and slight enhancement were appreciable (Fig. 7). In April, the little girl began specific treatment for t (1;19)-positive pre-B ALL, according to the AIEOP LLA 2017 Protocol. At the end of the steroid pre-phase with oral administration of high-dose prednisone for 7 days and a dose of intrathecal (IT) methotrexate, the little girl was considered prednisone poor responder, since the blasts in the peripheral blood were 1824/µL. Therefore, induction of remission was carried out using Protocol IA (methotrexate IT, PEG-L-asparaginase i.v., daunomycin i.v., vincristine i.v., prednisone p.o.) and subsequently Protocol IB (methotrexate IT, cyclophosphamide i.v., cytosine arabinoside i.v./subcutaneous, 6 mercaptopurine p.o.). In July at the end of the phase IB of induction and with the disease in complete remission, the ultrasound showed reduction in the size of the right ovarian lesion. The parents of the little girl were offered to carry on the treatment with consolidation therapy by applying the new AIEOP-BFM ALL 2017 protocol, according to which the prednisone-poor response to the steroid pre-phase is not, alone, a stratification criterion of high risk. Unfortunately, the little girl did not continue therapy because of her parents' decision to move her to another hospital.

Fig. 1.

Abdominal X-ray (erect view) shows air–fluid levels in the left hypochondrium/flank (black arrow) and poor representation of meteorism in rectum in the absence of free air

Fig. 2.

Abdominal ultrasonography shows an expansive formation in the left flank and in the mesogastrium, with “donut-like’’ aspect at the transverse scan (a) and “pseudo-kidney’’ in the longitudinal scan (b). The diameter (a) and length (b) of the mass are 3 and 6 cm, respectively

Fig. 3.

On ultrasound examination of the abdomen, the invaginated loop shows a focal thickening of the wall that appears remarkably hypoechoic (white circle in a) and extremely vascularized on color Doppler (white arrowheads in b)

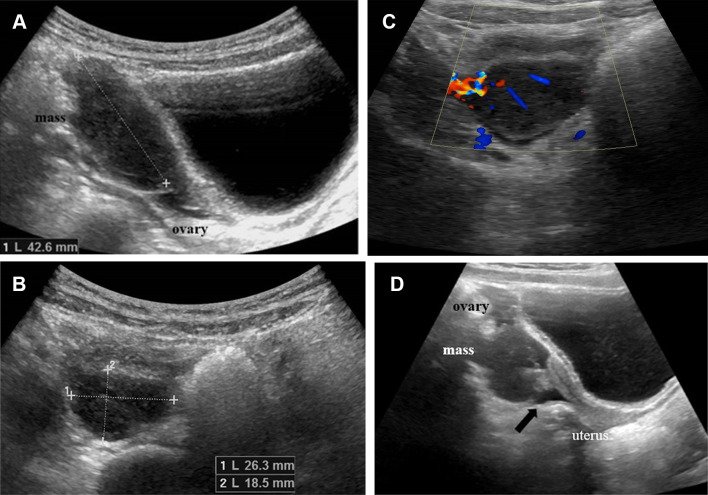

Fig. 4.

March 2019. The pelvic ultrasound shows the right ovary increased in size due to the presence of a great lesion of 43 mm on the longitudinal scan (a) and 26 × 18 mm on the transverse scan (b). The lesion exhibits inhomogeneous hypoechoic echostructure (a, b) and some vascular poles on color Doppler (c). A small amount of fluid in the pouch of Douglas is visible (black arrow in d)

Fig. 5.

Neoplastic cells diffusely infiltrate the small intestine. EE ×200. Inset: immunohistochemical demonstration of nuclear TdT

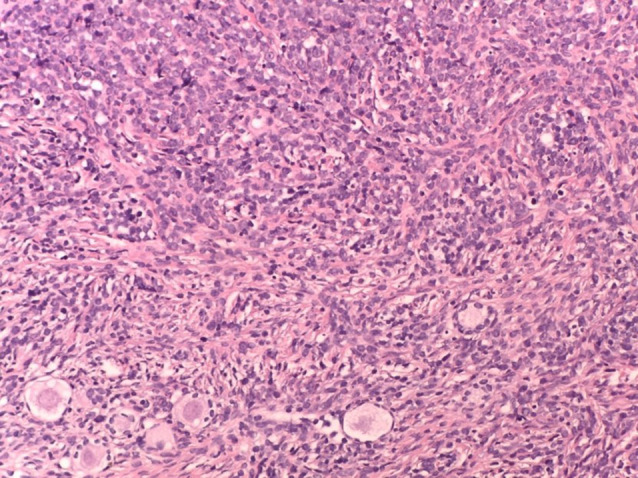

Fig. 6.

Neoplastic cells infiltrate the ovary sparing the primordial follicles. EE ×400

Fig. 7.

Axial (a) and coronal (b) post-contrast CT images of the pelvis show an enlarged right ovary with finely inhomogeneous density and slight enhancement (white arrows in a and b)

Discussion

In pediatric age, the B-ALL is the most frequent tumor as 85% of the ALLs originate from the precursors of the B lymphocytes [3, 5]. The initial presentation of the B-ALL is similar to that of the other forms of ALLs and is characterized by the clinical manifestations due to the bone marrow blast infiltration and, therefore, the marked reduction of hematopoietic activity [3]. Asthenia, pallor and tachycardia are caused by anemia; fever and recurrent or prolonged infections are linked to neutropenia and hemorrhagic manifestations (petechiae, gingivorrhagia, epistaxis) are due to thrombocytopenia [3, 5, 6]. Compared to T cell ALL (T-ALL), B-ALL is characterized by the tendency to manifest itself at the onset with bone pain which is present in 50% of cases and particularly affects long bones [3, 5, 7]. In addition, lymphadenomegaly and/or hepatosplenomegaly is often present at diagnosis in children with B-ALL; however, CNS involvement is rare and is more frequent in children with T-ALL [3, 6, 7]. The white blood cell count is variable in the initial CBC: it can be increased, reduced, but also be normal; thrombocytopenia and normocytic normochromic anemia are almost always present and the peripheral blood smear may not highlight blasts. The other laboratory investigations usually show nonspecific alterations, such as the increase in LDH and ESR [3, 7, 8]. In our case, the little girl did not show the typical clinical picture of leukemia. The ultrasound showed a voluminous invagination of the small intestine in the left flank and mesogastrium. In pediatric age, the small intestine invagination represents 1–10% of all invaginations and is almost always idiopathic in the first 2 years of life, while it is frequently secondary and linked to the presence of lead points in later ages [9, 10]. Ultrasound is the best method of diagnosing intestinal invagination, because of its high sensitivity and specificity, as well as its non-invasiveness and absence of ionizing radiation. In addition, ultrasound is a reliable diagnostic tool for the differential diagnosis between primary (PI) and secondary (SI) intestinal invagination, since it allows the identification of lead points. In children, the most common causes of SI are, intestinal duplication, intestinal polyps, allergic purpura and intestinal tumors (lymphoma is the most frequent, followed by adenoma, leiomyoma, lipoma and Ewing's tumor) [9–11]. In our case, the age of the little girl, the ultrasound findings of the invagination in the left flank and mesogastrium, spontaneous non-resolution of the invagination (guessed by the length of the invaginated loop which was 4.5 cm in longitudinal scan) and free fluid in the pelvis as well as the presence of intestinal dilation at the proximal end of the invagination on the abdominal X-ray oriented diagnosis toward an SI [10, 11]. Our hypothesis was reinforced by the presence of a pathological thickening of the wall of the invaginated loop on ultrasound, which subsequently proved to be the lead point of a jejunal–jejunal invagination; in fact, surgical exploration revealed a jejunal segment infiltrated by a jutting lesion in the intestinal lumen [11]. Finally, the ultrasound and laparoscopic findings of a voluminous ovarian lesion supported the diagnostic hypothesis of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) with onset at extranodal abdominal, and intestinal and ovarian localization. NHL represents 10–15% of all malignant neoplasms of the pediatric age and mainly affects children under 10 years of age [5, 12]. The most common subtype of B cell NHL is sporadic Burkitt lymphoma (BL), also known as “non-African", which occurs most frequently in children between 5 and 9 years of age and the average age of onset is 8 years [12]. The sporadic BL presents mainly as extranodal abdominal disease affecting the small intestine and colon [5, 12–14]. The growth of the neoplasm in the intestinal lumen can cause an SI as happened in our case. In fact, up to 18% of patients with abdominal BL have intestinal invagination as the first clinical sign [5, 11–14]. The ovary is another common extranodal site of BL which makes up 19% of adnexal lymphomas [12, 14]. The histological examination of intestinal and ovarian lesions of the little girl identified atypical lymphoid cells of the B line and the most relevant aspect for the diagnosis was the expression of TdT which is a nuclear enzyme recognizable in early lymphoid cells and is absent in mature B lymphocytes of the BL [3, 5–7, 12]. The histological report indicated a lymphoproliferative process compatible with B-ALL/B-LBL. The B-ALL and B-LBL are grouped together as neoplasms of the precursors of B lymphocytes and the distinction is conventionally based on the percentage of bone marrow infiltration by leukemic blasts. In 80% of cases, B cell acute lymphoproliferative neoplasm presents at onset with bone marrow blast infiltration, usually massive and greater than 25% and in this case the diagnosis is B-ALL; in 10% of cases, neoplasm is located in extramedullary sites with a blast percentage less than 25% in the bone marrow and in this case the diagnosis is B-LBL; the remaining 10% of cases are represented by mixed forms B-ALL/B-LBL [3, 5, 12, 15]. On the basis of the histological report, the little girl was hospitalized in the oncohematology department and was subjected to bone marrow aspiration which showed a percentage of blasts equal to 66% with pre-B immunophenotype due to the presence of cytoplasmic immunoglobulins (cIg+); in addition, the cytogenetic analysis of bone marrow revealed the translocation t (1;9) typical of the pre-B ALL [3, 15]. Therefore, the hematological findings diagnosed t (1;19)-positive pre-B ALL, with intestinal and ovarian localization at the onset.

Conclusions

Leukemia with initial extramedullary clinical presentation, which mimics solid tumors, is a rare event [4, 15]. In cases where leukemia is not suspected, extramedullary blastic disease is often misdiagnosed or belatedly diagnosed [4]. In the past, a high percentage of incorrect diagnoses were found, between 16 and 64%, and the diagnosis of lymphoma, hypothesized by us, confirmed the most frequent error in literature [4, 15]. Currently, the histopathological and immunohistochemical analysis of biopsies and surgical specimens allows the irrefutable identification of lymphoblastic infiltration in extramedullary sites, as happened in our case [4].

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 and its late amendments. Additional informed consented was obtained from all patients for which identifying information is not included in this article.

Human and animal rights

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.AIRTUM Working Group; CCM; AIEOP Working Group Italian cancer figures, report 2012: cancer in children and adolescents. Epidemiol Prev. 2013;37(1 Suppl 1):1–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Indolfi P, et al. Time trends of cancer incidence in childhood in Campania region: 25 years of observation. Ital J Pediatr. 2016;42(1):82. doi: 10.1186/s13052-016-0287-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roganovic J (2013) Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children. In: Guenova M, Balatzenko G (eds) Leukemia (InTech), Chapter 2, pp 39–74. 10.5772/45914 (ISBN 978-953-51-1127-6)

- 4.Urs L, et al. Leukemia presenting as solid tumors: report of four pediatric cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2008;11(5):370–376. doi: 10.2350/07-08-0326.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guillerman RP, et al. Leukemia and lymphoma. Radiol Clin N Am. 2011;49(4):767–797, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hunger SP, Mullighan CG. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(16):1541–1552. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1400972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oliveira CC, et al. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia: primary bone manifestation with hypercalcemia in a child. J Bras Patol Med Lab. 2017;53(1):61–64. doi: 10.5935/1676-2444.20170010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaime-Pérez JC, et al. Revisiting the complete blood count and clinical findings at diagnosis of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: 10-year experience at a single center. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. 2019;41(1):57–61. doi: 10.17533/udea.iatreia.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parikh M, et al. Does all small bowel intussusception need exploration? Afr J Paediatr Surg. 2010;7(1):30–32. doi: 10.4103/0189-6725.59358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartocci M, et al. Intussusception in childhood: role of sonography on diagnosis and treatment. J Ultrasound. 2014;18(3):205–211. doi: 10.1007/s40477-014-0110-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Draghi F, et al. Abdominal wall sonography: a pictorial review. J Ultrasound. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s40477-020-00435-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abramson SJ, Price AP. Imaging of pediatric lymphomas. Radiol Clin N Am. 2008;46(2):313–338. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehanna KH, et al. Burkitt's lymphoma presenting as jejunojejunal intussusception in a child: a case report. Int J Case Rep Images. 2017;8(2):96–100. doi: 10.5348/ijcri-201715-CR-10754. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biko DM, et al. Childhood Burkitt lymphoma: abdominal and pelvic imaging findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192(5):1304–1315. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geethakumari PR, et al. Extramedullary B lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (B-ALL/B-LBL): a diagnostic challenge. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2014;14(4):e115–e118. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]