Abstract

A newly developed immunochromatographic assay (MPB64-ICA) for identification of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex was evaluated with 20 reference strains of mycobacterial species and 111 clinical isolates. MPB64-ICA displayed a very strong reaction band with organisms belonging to the M. tuberculosis complex but not with mycobacteria other than M. tuberculosis (MOTT bacilli), except for one of four M. marinum strains tested and one M. flavescens strain, both of which gave very weak signals. The effectiveness of MPB64-ICA in combination with two liquid culture systems (MB-REDOX and MGIT) was tested. A total of 108 of 362 sputum specimens processed were positive for acid-fast bacilli. Samples taken from the cultures on the same days when either of the two culture systems became positive for mycobacteria were assayed with MPB64-ICA. Of 108 cultures with mycobacteria, 51 showed a positive signal with the test, in which the presence of the M. tuberculosis complex was demonstrated later by the Accuprobe for M. tuberculosis complex. In addition, MPB64-ICA could correctly detect the M. tuberculosis complex in mixed cultures of the M. tuberculosis complex and MOTT bacilli. These results indicate that MPB64-ICA can be easily used for rapid identification of the M. tuberculosis complex in combination with culture systems based on liquid media without any technical complexity in clinical laboratories.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a facultative intracellular bacterium that causes tuberculosis. Presently, tuberculosis affects 1.7 billion people worldwide. There are 8 million new cases and around 3 million deaths per year (30). The situation is further complicated by the emergence of multidrug-resistant strains (24, 31). Therefore, there is a need for rapid identification of mycobacteria and rapid drug susceptibility testing for effective treatment of the disease.

To identify mycobacteria, conventional biochemical tests are traditionally used (4, 14, 15, 29, 33). Key tests can be used to identify species, or further preliminary grouping may be used. Other approaches to identifying some species of mycobacteria are available. They include the p-nitrobenzoic acid (23, 28) and p-nitro-α-acetylamino-β-hydroxypropiophenone (17, 23) tests for discrimination of the M. tuberculosis complex from mycobacteria other than M. tuberculosis (MOTT bacilli); DNA probe methods for identification or confirmation of the M. tuberculosis complex, M. avium complex, M. kansasii, and M. gordonae (10, 11); and gas-liquid chromatography or high-performance liquid chromatography analyses for recognizing the patterns of the mycobacterial cell wall fatty acids or mycolic acids (26). The advantages of the last three methods are that they are capable of providing definitive identification within 2 to 4 h after adequate growth.

The immunogenic protein MPB64 has been found in unheated culture fluids of M. tuberculosis H37Rv and in some strains of M. bovis BCG (3, 12, 21). This antigen induced a strong delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction similar to that induced by purified protein derivatives in guinea pigs sensitized with these strains, whereas no reaction to MPB64 was observed with M. kansasii or M. intracellulare (12). The MPB64 antigen has been shown to be specific for the M. tuberculosis complex (12). Thus, MPB64 could be useful in studies on the pathogenesis and cell-mediated immunology of mycobacteria and in the development of diagnostic tests. In the present study, a newly developed (27) immunochromatographic assay (MPB64-ICA) using anti-MPB64 monoclonal antibodies for rapid discrimination between the M. tuberculosis complex and MOTT bacilli was evaluated with reference strains of 20 mycobacterial species, 111 clinical isolates, 108 liquid cultures inoculated with clinical specimens, and 7 M. bovis BCG substrains, and the results were compared with those of other identification tests.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mycobacterial strains and clinical specimens.

Reference strains of 20 Mycobacterium species (Table 1), 53 M. tuberculosis clinical isolates, 55 MOTT clinical isolates (3 strains of M. abscessus, 13 strains of M. avium complex, 2 strains of M. gordonae, 30 strains of M. kansasii, 3 strains of M. marinum, 3 strains of M. szulgai, and 1 unidentified strain), 7 M. bovis BCG substrains (Glaxo, Pasteur, Tice, Brazilian, Japanese, Russian, and Swedish), and 3 mixed cultures with M. tuberculosis and MOTT bacilli were used for this study. Clinical specimens, mostly sputum, were obtained from 362 different patients admitted to Fukujuji Hospital (Japan Anti-Tuberculosis Association, Kiyose-shi, Tokyo) with symptoms of pulmonary diseases.

TABLE 1.

Specificity of MPB64-ICA for identification of the M. tuberculosis complex

| Species | Strain | MPB64-ICA result |

|---|---|---|

| M. tuberculosis | KK 11-20 (H37Rv)a | + |

| M. africanum | ATCC 25420b | + |

| M. bovis | ATCC 19210 | + |

| M. kansasii | ATCC 12478 | − |

| M. marinum | ATCC 927 | − |

| M. simiae | ATCC 25275 | − |

| M. scrofulaceum | ATCC 19981 | − |

| M. gordonae | ATCC 14470 | − |

| M. asiaticum | KK 24-01 | − |

| M. avium | ATCC 25291 | − |

| M. intracellulare | ATCC 13950 | − |

| M. nonchromogenicum | ATCC 19530 | − |

| M. terrae | ATCC 15755 | − |

| M. szulgai | KK 32-01 | − |

| M. xenopi | ATCC 19250 | − |

| M. fortuitum | ATCC 6841 | − |

| M. abscessus | ATCC 19977 | − |

| M. chelonae | ATCC 35752 | − |

| M. flavescens | JATA 67-01a | +c |

| M. vaccae | KK 66-01 | − |

Mycobacteria Collection, Research Institute of Tuberculosis, Tokyo, Japan.

American Type Culture Collection.

The strain showed a very weak signal.

All specimens were decontaminated by the N-acetyl-l-cysteine–NaOH (NALC-NaOH) method, which was slightly modified from the original (16). Two volumes of NALC-NaOH solution (2% NaOH, 1.45% Na-citrate, 0.5% NALC) were mixed with the specimen on a test tube mixer for digestion, and the mixtures were allowed to stand for 15 min at room temperature. Ten volumes of 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) were added for dilution, and the mixtures were centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. After the supernatant fluids were carefully decanted, the resulting sediments were suspended in 1 ml of the same buffer.

Media and culture methods.

The Mycobacteria Growth Indicator Tube (MGIT) (Nippon Becton Dickinson Co., Ltd., Tokyo), which is a recently introduced nonradiometric culture system, uses an oxygen-quenched fluorescent indicator (1, 6, 8, 22). A fluorescent compound, ruthenium metal complex, is embedded in silicone on the bottom of 16- by 100-mm round-bottom tubes. Actively respiring mycobacteria consume the dissolved oxygen and allow the fluorescence to be observed with a 365 nm UV transilluminator. The MGIT contains 4 ml of modified Middlebrook 7H9 liquid medium. The supplement contains casein peptone, albumin, dextrose, catalase, oleic acid, polymyxin B, amphotericin B, nalidixic acid, trimethoprim, and azlocillin.

MB-REDOX (Biotest AG, Frankfurt, Germany) is serum-supplemented, modified Kirchner medium (4 ml) containing a colorless tetrazolium salt, special vitamin complex, and the antibiotic admixture PACT (polymixin B, amphotericin B, carbenicillin, and trimethoprim) (7). In this method, the tetrazolium salt is reduced by the redox system of the mycobacteria to a brownish formazan. This formazan is water insoluble and is easily detected by the naked eye. The MB-REDOX medium was kindly provided by Nissui Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan.

A 0.2-ml portion of each pretreated specimen was inoculated into MGIT and MB-REDOX tubes. All media were incubated at 37°C and checked twice a week for the first 4 weeks and once a week for the remaining culture time.

Identification of mycobacterial isolates.

All isolates were differentiated and identified by an RNA-DNA hybridization assay (4, 10, 11) with commercial kits for culture confirmation and identification of species belonging to the M. tuberculosis complex and M. avium complex (Gen-Probe, San Diego, Calif.) and by conventional culturing or biochemical testing (4, 14). Niacin test strips were purchased from Kyokuto Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan (15, 33).

MPB64-ICA.

MPB64-ICA is a rapid immunochromatographic identification test for the M. tuberculosis complex that uses anti-MPB64 monoclonal antibodies (27). Monoclonal antibodies were produced from hybridomas obtained by the fusion of P3U1 myeloma cells with spleen cells of mice immunized with an MPB64 antigen. The test strip consists of a sample pad, a reagent pad, a nitrocellulose membrane, and an absorbent pad. The antibodies were immobilized on the nitrocellulose membrane as the capture reagent (test line). Secondary antibodies, which recognized another epitope of the antigen, conjugated with colloidal gold particles were used for antigen capture and detection in a sandwich-type assay.

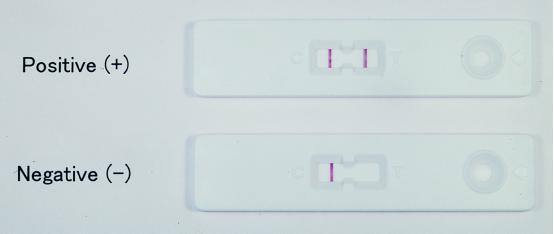

As the test sample applied in the sample well flows laterally through the membrane, the antibody-colloidal gold conjugate binds to the MPB64 antigen in the sample. The complex then flows further and binds to the monoclonal antibodies on the solid phase in the test zone, producing a red band. In the absence of MPB64, there is no line in the positive reaction zone. The liquid continues to migrate along the membrane and produces a red band in the control zone, demonstrating that the reagents are functioning properly (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Identification of the M. tuberculosis complex by MPB64-ICA. Negative, only one reddish-purple band appears in the control (C) window. Positive, in addition to the control band, a clear distinguishable reddish-purple band also appears in the test (T) window.

For sample preparation from solid cultures, a loopful (1 μl) of growth was vortexed for 1 min in a screw-capped tube containing 200 μl of 10 mM phosphate buffer–0.1% Tween 80 and 5 to 10 pieces of glass beads. One hundred microliters of each treated sample was applied to the sample wells and they were allowed to stand at room temperature for 15 min. If the sample contains MPB64, a red band is produced in the test zone. Liquid cultures (100 μl) were applied directly to the sample wells without use of the sample preparation procedure.

RESULTS

Reference strains of 20 mycobacterial species were subjected to MPB64-ICA for identification of the M. tuberculosis complex. Samples prepared from Ogawa egg slants were added to the sample wells of the cassette. As shown in Table 1, strong reaction bands against the bacteria belonging to the M. tuberculosis complex, M. tuberculosis, M. africanum, and M. bovis were demonstrated, while no positive signal was observed for the MOTT bacilli tested, except for M. flavescens, which showed a very weak signal. Next, to further confirm the specificity of the test, the results with MPB64-ICA were compared with those of the Accuprobe-M. tuberculosis complex culture confirmation test (Accuprobe) and the niacin accumulation test with 111 mycobacterial cultures. These included 53 M. tuberculosis isolates, 55 MOTT isolates, and 3 mixed cultures with M. tuberculosis and MOTT bacilli (Table 2). All 53 M. tuberculosis isolates and the 3 mixed cultures were positive for the M. tuberculosis complex by both the MPB64-ICA and Accuprobe tests. On the other hand, the niacin test failed to obtain a positive result from the three mixed cultures, which were confirmed to contain the M. tuberculosis complex by the MPB64-ICA and Accuprobe tests. MPB64-ICA showed a positive result for one of three M. marinum clinical isolates tested, although the reaction was very weak. Of 55 MOTT cultures, one was positive in the niacin test; this was an M. kansasii culture and did not seem to contain M. tuberculosis according to the results of the other two tests.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of the results obtained by MPB64-ICA, Accuprobe for M. tuberculosis complex, and niacin accumulation tests

| Species (no. of isolates) | No. of positive results with the following test:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| MPB64-ICA | Accuprobe | Niacin | |

| M. tuberculosis (53) | 53 | 53 | 53 |

| MOTT | |||

| M. kansasii (30) | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| M. avium complex (13) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| M. marinum (3) | 1b | 0 | 0 |

| M. gordonae (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| M. szulgai (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| M. abscessus (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unidentified (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mixed (MOTTa + M. tuberculosis) (3) | 3 | 3 | 0 |

Two M. avium complex and one M. gordonae.

The strain showed a very weak signal.

To investigate the sensitivity of the assay, 10-fold dilutions of the M. bovis BCG Japanese strain grown in Middlebrook 7H9 liquid medium were made in cold 10 mM phosphate buffer containing 0.1% Tween 80. The organisms were washed once with the same buffer before the dilution to remove MPB64 antigen secreted in the culture medium. The number of organisms was determined on Middlebrook 7H11 agar plates. Each dilution containing M. bovis BCG organisms was vortexed in the tube containing glass beads and then applied to the test cassette. The detection limit of MPB64-ICA was estimated as 105 CFU/ml (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Analytical sensitivity of MPB64-ICAa

| No. of mycobacteria (log CFU/ml) |

MPB64-ICA result |

|---|---|

| 7 | +++ |

| 6 | ++ |

| 5 | + |

| 4 | ± |

| 3 | − |

| 2 | − |

Tenfold dilutions of M. bovis BCG grown in Middlebrook 7H9 liquid medium were made in 10 mM phosphate buffer–0.1% Tween 80 and vortexed, and then 100 μl of each dilution was assayed by MPB64-ICA.

The usefulness of the culture systems based on liquid media had been confirmed by many studies. In this study, we tried to do early confirmation of the M. tuberculosis complex in liquid cultures by MPB64-ICA. Two culture systems, the MGIT and MB-REDOX systems, were used for the evaluation. Samples taken from the cultures when they showed a positive signal for mycobacteria in the liquid cultures were assayed with MPB64-ICA. A total of 108 of 362 sputum specimens processed were positive for mycobacteria (acid-fast bacilli). Fifty-one cultures tested positive with MPB64-ICA, and the presence of the M. tuberculosis complex in these cultures was demonstrated by other confirmation tests (Table 4). One culture was a mixed culture with M. tuberculosis complex and M. avium complex bacilli; the M. tuberculosis complex was detected exactly by the test. All 57 cultures with MOTT bacilli were negative with MPB64-ICA. The mean times for the confirmation of the M. tuberculosis complex were 15 and 16.5 days from processing of the specimens with the MB-REDOX and MGIT systems, respectively.

TABLE 4.

Rapid confirmation of M. tuberculosis complex in liquid cultures by MPB64-ICAa

| Species (no. of isolates) | No. of isolates with the following MPB64-ICA result:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | |

| M. tuberculosis (50) | 50 | 0 |

| MOTT (57) | 0 | 57 |

| Mixedb (1) | 1 | 0 |

| Total (108) | 51 | 57 |

Sputum specimens were cultured with the MB-REDOX and MGIT systems. Samples from positive cultures were assayed by MPB64-ICA.

A mixed culture with the M. tuberculosis complex and M. kansasii.

It is well known that M. bovis BCG vaccine strains can be divided into two groups on the basis of several features, such as the number of IS6110 copies (9, 25) and the presence of MPB64 antigen (12, 21) and methoxymycolates (19). As shown in Table 5, these two groups of the substrains were clearly differentiated by MPB64-ICA.

TABLE 5.

Properties of two groups of M. bovis BCG strains

DISCUSSION

The immunochromatographic test used here is of a new generation and is one of the simplest and fastest tests to perform. The MPB64 antigen was found in the culture fluid of only the M. tuberculosis complex and some strains of M. bovis BCG (12, 21). The specificity of the antigen for the M. tuberculosis complex was confirmed by a radioimmunoassay-inhibition assay using anti-MPB64 antibodies (12). The purpose of this study was to evaluate the newly developed immunochromatographic assay, MPB64-ICA (27), for identification of the M. tuberculosis complex with the reference strains of the clinically important mycobacterial species and with clinical isolates. MPB64-ICA showed a very strong signal with the organisms belonging to the M. tuberculosis complex but not with MOTT bacilli, except for one of four strains of M. marinum tested and one M. flavescens strain, which showed a very weak signal (Tables 1 and 2). These two species may be easily differentiated from the M. tuberculosis complex by the following properties: M. marinum has photochromogenic and smooth-type colonies on solid media and is isolated from skin lesions in most cases (5, 29), M. flavescens has pigmented, smooth-type colonies (29), and both normally grow rapidly.

The MPB64 antigen is found in the culture fluids of the M. tuberculosis complex. The antigen is secreted in significant amounts during the early period of culturing and decreases with longer cultivation (21). A gene cloning study has shown that the antigen is synthesized with a signal peptide characteristic of a secreted protein (32).

During the past decade, culture systems based on liquid media have been introduced for primary isolation of mycobacteria from clinical specimens in many countries (1, 2, 6–8, 13, 18, 20, 22). Here we used two culture systems with different detection systems for mycobacteria, MB-REDOX and MGIT. A total of 108 cultures of 362 sputum specimens processed were positive for acid-fast bacilli in these two systems. When the samples from these positive cultures were assayed with MPB64-ICA, 51 showed positive results for the MPB64 antigen (Table 4). In the Accuprobe test, all 51 cultures were confirmed to contain the M. tuberculosis complex bacilli. One culture was a mixture of M. tuberculosis complex and M. avium complex, again demonstrating the usefulness of the test in mixed cultures. The mean detection times for the M. tuberculosis complex were 15 and 16.5 days with the MB-REDOX and MGIT systems, respectively. A positive signal for MPB64-ICA was obtained from all of 51 cultures on the same days when these culture systems had become mycobacterium positive. It is very important to discriminate early between M. tuberculosis and MOTT bacilli for appropriate management of the patients and effective treatment of the disease. MPB64-ICA can be easily used for rapid identification of the M. tuberculosis complex in combination with the culture systems based on liquid media without any troublesome sample preparation in a laboratory.

Mixed mycobacterial infections with two species occur less frequently in human immunodeficiency virus negative patients, but they are not rare and are difficult to diagnose by conventional methods. In this study, we tested four mixed cultures (Tables 2 and 4). All were cultures with the M. tuberculosis complex and MOTT bacilli; two contained the M. avium complex and one each contained M. kansasii and M. gordonae. MPB64-ICA could detect the M. tuberculosis complex in all of these cultures. The Accuprobe test also confirmed exactly the presence of the M. tuberculosis complex, but the niacin test failed to detect it in all four cultures.

When fresh M. bovis BCG grown in a liquid medium was used for the evaluation, the analytical sensitivity of MPB64-ICA was calculated as 105 CFU/ml (Table 3), a value similar to that for the Accuprobe test (10, 11). Therefore, this test should not be used directly on fresh clinical specimens.

M. bovis BCG is isolated occasionally from individuals with lymphadenitis occurring after M. bovis BCG vaccination or from bladder cancer patients with M. bovis BCG instillation therapy. However, it is not easy to differentiate between M. tuberculosis and M. bovis BCG. Harboe et al. showed that the Brazilian, Japanese, Russian, and Swedish strains of M. bovis BCG possessed an MPB64 antigen but that the Pasteur, Glaxo, and Tice strains did not (12). In the present study, it was found that two groups of M. bovis BCG could be clearly differentiated by MPB64-ICA (Table 5). In countries where the Pasteur, Glaxo, or Tice strain of M. bovis BCG was used for vaccination, M. bovis BCG isolates may be easily discriminated from M. tuberculosis by MPB64-ICA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partly supported by Health Sciences Research grants from the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Japan (Research on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases) and by the Tuberculosis and Leprosy panel, U.S.-Japan Cooperative Medical Science Program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe C, Hirano K, Wada M. Evaluation of the Mycobacteria Growth Indicator Tube system using oxygen sensitive fluorescent sensor for rapid detection of mycobacteria. In: Casal M, editor. Clinical mycobacteriology. Barcelona, Spain: Prous Science; 1998. pp. 175–180. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abe C, Hosojima S, Fukasawa Y, Kazumi Y, Takahashi M, Hirano K, Mori T. Comparison of MB-Check, BACTEC, and egg-based media for recovery of mycobacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:878–881. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.4.878-881.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abou-Zeid C, Harboe M, Rook G A W. Characterization of the secreted antigens of Mycobacterium bovis BCG: comparison of the 46-kilodalton dimeric protein with proteins MPB64 and MPB70. Infect Immun. 1987;55:3213–3214. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.12.3213-3214.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Society for Microbiology. Clinical microbiology procedures handbook. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. Section 3. Mycobacteriology. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aronson J D. Spontaneous tuberculosis in salt fish. J Infect Dis. 1926;39:315. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Badak F Z, Kiska D L, Setterquist S, Hartley C, O'Conell M A, Hopfer R L. Comparison of Mycobacteria Growth Indicator Tube with BACTEC 460 for detection and recovery of mycobacteria from clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2236–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2236-2239.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cambau E, Wichlacz C, Truffot-Pernot C, Jarlier V. Evaluation of the new MB Redox system for detection of growth of mycobacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2013–2015. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.2013-2015.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casal M, Gutierrez J, Vaquero M. Comparative evaluation of the Mycobacteria Growth Indicator Tube with the BACTEC 460TB system and Löwenstein-Jensen medium for isolation of mycobacteria from clinical specimens. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1997;1:81–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fomukong N G, Dale J W, Osborn T W, Grange J M. Use of gene probes on the insertion sequence IS986 to differentiate between BCG vaccine strains. J Appl Bacteriol. 1992;72:126–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1992.tb01813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gen-Probe, Inc. Accuprobe mycobacterium culture confirmation tests. San Diego, Calif: Gen-Probe, Inc.; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goto M, Oka S, Okuzumi K, Kimura S, Shimada K. Evaluation of acridinium ester-labeled DNA probes for identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium-Mycobacterium intracellulare complex in culture. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2473–2476. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.11.2473-2476.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harboe M, Nagai S, Patarroyo M E, Torres M L, Ramirez C, Cruz N. Properties of proteins MPB64, MPB70, and MPB80 of Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Infect Immun. 1986;52:293–302. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.1.293-302.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isenberg H D, D'Amato R F, Heifets L, Murray P R, Scardamaglia M, Jacobs M C, Alperstein P, Niles A. Collaborative feasibility study of a biphasic system (Roche Septi-Chek AFB) for rapid detection and isolation of mycobacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:1719–1722. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.8.1719-1722.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kent P T, Kubica G P. Public health mycobacteriology. A guide for the level III laboratory. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Konno K. New chemical method to differentiate human-type tubercle bacilli from other mycobacteria. Science. 1956;124:985. doi: 10.1126/science.124.3229.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kubica G P W, Dye E, Cohn M L, Middlebrook G. Sputum digestion and decontamination with N-acetyl-l-cysteine-sodiumhydroxide for culture of mycobacteria. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1963;87:775–779. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1963.87.5.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laszlo A, Siddiqi E. Evaluation of a rapid radiometric differentiation test for the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex by selective inhibition with p-nitro-α-acetylamino-β-hydroxypropiophenone. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;19:694–698. doi: 10.1128/jcm.19.5.694-698.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Middlebrook G, Reggiardo Z, Tigertt W D. Automatable radiometric detection of growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in selective media. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1977;115:1066–1069. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1977.115.6.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minnikin D E, Parlett J H, Magnusson M, Ridell M, Lind A. Mycolic acid patterns of representatives of Mycobacterium bovis BCG. J Gen Microbiol. 1984;130:2733–2736. doi: 10.1099/00221287-130-10-2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morgan M A, Horstmeier C D, DeYoung D R, Roberts G D. Comparison of a radiometric method (BACTEC) and conventional culture media for recovery of mycobacteria from smear-negative specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;18:384–388. doi: 10.1128/jcm.18.2.384-388.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagai S, Wiker H G, Harboe M, Kinomoto M. Isolation and partial characterization of major protein antigens in the culture fluid of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1991;59:372–382. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.1.372-382.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfyffer G E, Welscher H-M, Kissling P, Cieslak C, Casal M J, Gutierrez J, Rüsch-Gerdes S. Comparison of the Mycobacteria Growth Indicator Tube (MGIT) with radiometric and solid culture for recovery of acid-fast bacilli. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:364–368. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.2.364-368.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rastogi N, Goh K S, David H L. Selective inhibition of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex by p-nitro-α-acetylamino-β-hydroxypropiophenone (NAP) and p-nitrobenzoic acid (PNB) used in 7H11 agar medium. Res Microbiol. 1989;140:419–423. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(89)90017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snider D E, Roper W L. The new tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:703–705. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199203053261011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takahashi M, Kazumi Y, Fukasawa Y, Hirano K, Mori T, Dale J W, Abe C. Restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of epidemiologically related Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates. Microbiol Immunol. 1993;37:289–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1993.tb03212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tisdall P A, DeYoung D R, Roberts G D, Anhalt J P. Identification of clinical isolates of mycobacteria with gas-liquid chromatography: a 10-month follow-up study. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;16:400–402. doi: 10.1128/jcm.16.2.400-402.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomiyama T, Matsuo K, Abe C. Rapid identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by an immunochromatography using anti-MPB64 monoclonal antibodies. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1997;1(Suppl. 1):S59. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsukamura M, Tsukamura S. Differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium bovis by p-nitrobenzoic acid susceptibility. Tubercle. 1964;45:64–65. doi: 10.1016/s0041-3879(64)80091-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wayne L G, Kubica G P. The mycobacteria. In: Sneath P H A, Mair N S, Sharp M E, Holt J G, editors. Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 2. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1986. pp. 1435–1457. [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization. Report of the tuberculosis epidemic. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization. Anti-tuberculosis drug resistance in the world. The WHO/IUATLD global project on anti-tuberculosis drug-resistance surveillance, 1994–1997. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamaguchi R, Matsuo K, Yamazaki A, Abe C, Nagai S, Terasaka K, Yamada T. Cloning and characterization of the gene for immunogenic protein MPB64 of Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Infect Immun. 1989;57:283–288. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.1.283-288.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Young W D, Jr, Maslansky A, Lefar M S, Kronish D P. Development of a paper strip test for detection of niacin produced by mycobacteria. Appl Microbiol. 1970;10:939–945. doi: 10.1128/am.20.6.939-945.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]