Abstract

In a recent issue of Clinical Kidney Journal (CKJ), Gutierrez-Peña et al. reported a high incidence and prevalence of advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) in Aguascalientes, Mexico. This contradicts Global Burden of Disease estimates, which should be updated. A key component of this high burden of CKD relates to young people ages 20–40 years in whom the cause of CKD was unknown [CKD of unknown aetiology (CKDu)]. The incidence of kidney replacement therapy in this age group in Aguascalientes is among the highest in the world, second only to Taiwan. However, high-altitude Aguascalientes, with a year-round average temperature of 19°C, does not fit the geography of other CKDu hotspots. Furthermore, kidney biopsies in young people showed a high prevalence of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Potential causes of CKDu in Aguascalientes include the genetic background (no evidence, although podocytopathy genes should be explored) and environmental factors. The highest prevalence of CKD was found in Calvillo, known for guava farming. Thus guava itself, known to contain bioactive, potentially nephrotoxic molecules and pesticides, should be explored. Additionally, there are reports of water sources in Aguascalientes contaminated with heavy metals and/or pesticides. These include fluoride (increased levels found in Calvillo drinking water) as well as naturally occurring arsenic, among others. Fluoride may accumulate in bone and cause kidney disease years later, and maternal exposure to excess fluoride may cause kidney disease in offspring. We propose a research agenda to clarify the cause of CKDu in Aguascalientes that should involve international funders. The need for urgent action to identify and stem the cause of the high incidence of CKD extends to other CKD hotspots in Mexico, including Tierra Blanca in Veracruz and Poncitlan in Jalisco.

Keywords: burden of disease, CKD hotspot, CKD of uncertain aetiology, fluoride, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, Mexico

CKD HOTSPOTS AND CKDu

In 2014, a Clinical Kidney Journal (CKJ) manuscript first defined chronic kidney disease (CKD) hotspots as countries, regions, communities or ethnicities with an incidence of CKD higher than average [1]. Since then, the term has been popularized, as it may provide information leading to identification of causative agents that explain the high incidence of CKD in certain communities. Earlier, a novel form of CKD of uncertain aetiology (CKDu) was described in several subtropical regions and first named as such in Sri Lanka, although in Central America it was known as Mesoamerican nephropathy [2, 3]. Although Mesoamerican nephropathy was initially described in sugarcane workers and thought to be an occupational disease, children residing in regions of Nicaragua at high risk for Mesoamerican nephropathy may experience subclinical kidney injury prior to occupational exposures [4]. Indeed, a systematic review and meta-analysis not only showed an association with male gender, water intake and lowland altitude, potentially reflecting higher temperatures and agricultural work as drivers, but was also associated with a family history of CKD, potentially implying a genetic background or common intrafamilial exposure [5, 6] (Figure 1). Moreover, a high water intake may represent a risk if such water is contaminated. However, there were no significant associations with pesticide exposure, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs intake, heat stress or alcohol consumption.

FIGURE 1:

Conceptual framework for CKDu pathogenesis. Based on available evidence regarding the concentration of CKD cases within certain geographic locations and families, as well on the association with certain environments and occupations, a conceptual framework implying a genetic susceptibility background in association or interacting with environmental exposures is a reasonable starting point to unravel the pathogenesis of CKDu.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF CKD IN MEXICO

Mexico is among the countries with the highest incidence and prevalence of CKD. According to the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) database 2019, the incidence of CKD is 457/100 000 and the prevalence is 13 017/100 000. The states with the highest prevalence and incidence in 2019 were Mexico City, Veracruz, Morelos and Tamaulipas [7] (Table 1). The annual increase in mortality rate due to CKD reported by the GBD from 1990 to 2019 was 4.85%/year [7]. Diabetes and hypertension, two of the main diagnosed causes of CKD, are highly prevalent in Mexico. According to data from the 2018 National Health and Nutrition Survey, 10.3% of the population ≥20 years of age reported a diagnosis of diabetes and 18.4% of hypertension [8].

Table 1.

CKD prevalence, incidence and age standardized mortality rate according to the GBD study (1.2) and kidney transplant status (CENATRA study) in Mexico by state

| State | CKD prevalence/ 100 000 [7] | CKD incidence/ 100 000 [7] | Age-standardized CKD mortality rate (95% UI) [8] |

Kidney transplants (n in 2019) [9] | Total population 2020 [10] | Donation rate (pmp) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | ||||||

| Aguascalientes | 12 195 | 426 | 30.4 (28.3–32.4) | 29.7 (28.0–31.7) | 110 | 1 425 607 | 77.46 |

| Baja California | 12 187 | 428 | 32.1 (30.2–34.2) | 29.2 (27.5–31.1) | 62 | 3 769 020 | 16.4 |

| South Baja California | 11 649 | 401 | 26.3 (24.5–28.4) | 22.7 (21.1–24.4) | 16 | 798 447 | 20.25 |

| Campeche | 12 266 | 419 | 20.4 (19.0–21.8) | 25.8 (23.8–27.6) | 0 | 928 363 | 0 |

| Chiapas | 10 434 | 354 | 22.0 (20.6–23.6) | 25.5 (23.8–27.2) | 6 | 3 146 771 | 1.93 |

| Chihuahua | 12 389 | 433 | 31.8 (29.8–33.7) | 28.4 (26.7–30.3) | 30 | 731 391 | 41.09 |

| Coahuila | 13 080 | 476 | 36.6 (34.3–38.8) | 32.9 (31.0–35.0) | 136 | 5 543 828 | 24.54 |

| Colima | 13 226 | 468 | 32.6 (30.7–35.2) | 30.7 (28.7–32.8) | 0 | 3 741 869 | 0 |

| Durango | 12 453 | 421 | 28.7 (26.9–30.7) | 27.6 (25.7–29.4) | 0 | 1 832 650 | 0 |

| Estado De Mexico | 12,667 | 460 | 32.4 (30.5–34.6) | 33.1 (31.2–35.1) | 95 | 16 992 418 | 5.59 |

| Mexico City | 16 000 | 575 | 34.2 (32.2–36.3) | 26.4 (24.9–28.0) | 831 | 9 209 944 | 90.32 |

| Guanajuato | 12 928 | 452 | 38.9 (36.5–41.6) | 36.8 (34.5–39.1) | 210 | 6 166 934 | 34.09 |

| Guerrero | 11 771 | 440 | 20.7 (19.3–22.1) | 18.2 (16.9–19.6) | 1 | 3 540 685 | 0.28 |

| Hidalgo | 13 271 | 460 | 26.1 (24.5–28.0) | 27.3 (25.6–28.8) | 32 | 3 082 841 | 10.38 |

| Jalisco | 13 075 | 454 | 33.1 (31.3–35.0) | 33.2 (31.3–35.1) | 624 | 8 348 151 | 74.82 |

| Michoacan | 12 879 | 431 | 26.1 (24.5–27.8) | 26.2 (24.7–27.9) | 46 | 4 748 846 | 9.70 |

| Morelos | 13 736 | 488 | 28.7 (27.0–30.3) | 27.9 (26.1–29.8) | 22 | 1 971 520 | 11.16 |

| Nayarit | 12 940 | 435 | 24.5 (23.0–26.3) | 22.9 (21.3–24.6) | 1 | 1 235 456 | 0.81 |

| Nuevo Leon | 13 350 | 481 | 29.7 (28.0–31.6) | 29.2 (27.5–30.9) | 146 | 5 784 442 | 25.25 |

| Oaxaca | 13 095 | 445 | 29.4 (27.5–31.4) | 34.2 (32.1–36.2) | 4 | 4 132 148 | 0.96 |

| Puebla | 12 614 | 443 | 36.1 (34.0–38.5) | 37.9 (35.8–40.1) | 139 | 6 583 278 | 21.12 |

| Queretaro | 12 241 | 426 | 30.8 (28.9–33.1) | 31.6 (29.4–33.6) | 47 | 2 368 467 | 19.91 |

| Quintana Roo | 10 367 | 353 | 19.3 (17.8–20.8) | 20.6 (19.0–22.2) | 0 | 1 857 985 | 0 |

| San Luis Potosi | 12 849 | 428 | 22.5 (21.2–24.0) | 23.8 (22.2–25.2) | 122 | 2 822255 | 43.26 |

| Sinaloa | 13 353 | 459 | 20.7 (19.4–22.0) | 19.4 (18.1–20.7) | 13 | 3 026 943 | 4.30 |

| Sonora | 12 660 | 438 | 27.9 (26.0–29.8) | 28.2 (26.4–30.0) | 51 | 2 944 840 | 17.34 |

| Tabasco | 12 842 | 458 | 26.2 (24.5–28.0) | 28.3 (26.4–30.1) | 18 | 2 402 598 | 7.50 |

| Tamaulipas | 13 702 | 486 | 28.3 (26.6–30.1) | 25.9 (24.4–27.5) | 11 | 3 527 735 | 3.12 |

| Tlaxcala | 13 031 | 461 | 38.0 (35.5–40.5) | 40.1 (37.5–42.7) | 5 | 1 342 977 | 3.73 |

| Veracruz | 14 637 | 515 | 25.2 (23.7–26.8) | 23.9 (22.4–25.4) | 122 | 8 062 579 | 15.13 |

| Yucatan | 12 792 | 430 | 22.7 (21.3–24.3) | 24.8 (23.2–26.2) | 49 | 2 320 898 | 21.12 |

| Zacatecas | 12 935 | 430 | 23.7 (22.2–25.4) | 23.4 (22.0–25.0) | 10 | 1 662 138 | 6.02 |

Aguascalientes is the location with the highest incidence and prevalence of CKD.

UI: uncertainty interval.

Mexico has no centralized national registry for kidney disease. Epidemiological data on patients with CKD receiving medical attention in health systems showed a male:female ratio of 1.2:1.0, with a mean age of 60 years [11]. Jalisco kidney replacement therapy (KRT) data are the most widely known internationally and have long been part of the US Renal Data System (USRDS) international comparisons [12]. The KEEP Mexico study from Mexico City and Jalisco found 7% of patients in CKD category G1, 8 and 16% in G2, 6 and 9% in G3 and 1% in G4–5, respectively [13]. Primary causes were diabetes mellitus (DM; 53%), hypertension (34%), glomerular disease (7%), polycystic kidney disease (2%), inborn disease (2%) and others (2%) [11]. Strikingly, CKDu apparently accounted for <2% of patients with CKD. KRT by dialysis mainly involves peritoneal dialysis (PD; 59%, of which 27% corresponds to ambulatory PD and 32% of continuos ambulatory PD) and haemodialysis (41%) [14]. The states with the highest rates of transplant were Mexico City, Jalisco, Aguascalientes, San Luis Potosi and Coahuila.

CKDu IN MEXICO

CKDu has been reported in Mexico. In the period 2008–2018, 30 of 57 (53%) patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) referred for renal transplant to the Instituto Nacional de Cardiologia met the criteria for CKDu [15]. Biopsies in five of six patients showed findings compatible with Mesoamerican nephropathy. Tierra Blanca in Veracruz and Poncitlan in Jalisco have been identified as CKDu hotspots (Figure 2A). A cross-sectional study with 7717 participants ages 20–60 years from communities in Tierra Blanca reported a prevalence of 25% of probable CKD, and 44% of them could be considered CKDu cases. The CKDu hotspot status of Poncitlan is supported by population screenings for CKD that have been performed in the State of Jalisco since 2007. The CKD prevalence in Poncitlan was 20.1, versus 10.4% in the rest of the state, with KRT prevalence being 2-fold higher than the rest of the state [16]. ESKD cases from Tierra Blanca represent 25% of the state’s waiting list for kidney transplantation, although the municipality represents only 1.3% of the state’s population.

FIGURE 2:

Location and geography of Aguascalientes. (A) Location of Aguascalientes within Mexico as well as of the CKD hotspots in Jalisco, Veracruz and Mexico City [17]. (B) Geography of Aguascalientes. The two main river systems (San Pedro and Calvillo Rivers) drawing water from the same mountain range. The locations of Calvillo and Tunel de Potrerillo/Boca Tunel are shown. https://www.freeworldmaps.net/.

AGUASCALIENTES: LIKELY THE HOTTEST CKD HOTSPOT IN MEXICO

In a recent issue of CKJ, Gutierrez-Peña et al. [18] reported on the Aguascalientes State Registry of CKD and Renal Biopsy, providing data on KRT incidence (2019) and prevalence (April 2020) and kidney biopsy diagnoses. The registry included all patients with KRT in private and public institutions from Aguascalientes State Health Services. Aguascalientes is a small state located at high altitudes in central Mexico, with a dry climate characterized by stable yearlong temperatures (average 19°C) (Figure 2). Data from the Aguascalientes State Registry of CKD were recently incorporated into USRDS international comparisons and 2018 Aguascalientes data are part of the USRDS 2020 report [19]. Aguascalientes has emerged as one of the hottest CKD hotspots in Mexico and among the hottest in the world for 20- to 40-year-olds (Figure 3A).

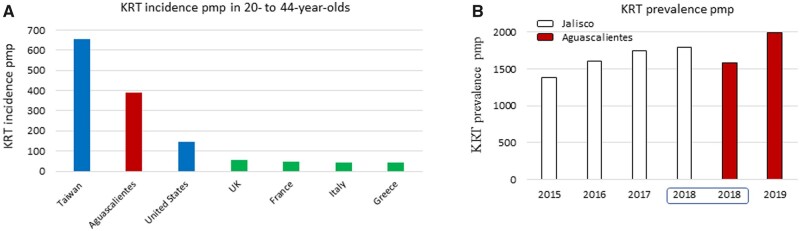

FIGURE 3:

Epidemiology of CKD in Aguascalientes, international perspective. (A) KRT incidence pmp in 20- to 44-year-olds. (B) KRT prevalence pmp in Jalisco and Aguascalientes. Up to 2018, source was USRDS [12]; for 2019, source was Gutierrez-Peña et al. [18].

The 2020 prevalence and 2019 incidence of KRT in Aguascalientes were 1997 per million population (pmp) and 336 pmp, respectively. More strikingly, the average age was 46 years, with peaks at ages 20–40 and 50–70 years. In contrast, KEEP Mexico data from Mexico City and Jalisco showed CKDu was the main cause of KRT, followed by diabetes. CKDu was by far the most common cause (73% of cases) of KRT in patients 20–40 years of age. Patients were classified as CKDu if there was no history of DM, glomerulopathy, long-standing hypertension or any other identifiable cause such urinary tract or polycystic kidney disease. Kidney biopsy results supported the high prevalence of a form of CKDu characterized by focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) associated to other features of vascular and tubulointerstitial non-specific CKD. These biopsies were mainly obtained from persons ages 21–30 years.

These results are significant since they point to unidentified pockets of CKD within Mexico and emphasize the need for country-wide statistics. Indeed, the GBD ranked Aguascalientes 27th out of 32 Mexican states in terms CKD prevalence. Based on data from Gutierrez-Peña et al. [18], these estimates may be way off the mark. As an alternative explanation, there might be suboptimal provision or registration of KRT in other Mexican states. The annual 2020 USRDS report displays Aguascalientes data for 2018 with more granularity than the data from Jalisco, the traditional source of Mexican information for USRDS international comparisons [19]. One of the most worrisome aspects of the report is the very high incidence of KRT in Aguascalientes among younger people (20–40 years of age), second only to Taiwan, the country with the highest incidence of KRT in the world (Figure 3A). Moreover, the most recent Aguascalientes data, reported by Gutierrez-Peña et al. [18], may position Aguascalientes above Jalisco in terms of KRT prevalence (Figure 3B).

The second issue raised is about the cause of such high KRT incidence and prevalence. Lessons learned in this regard may help other CKD hotspots. One of the most remarkable findings was the high prevalence of renal biopsy registry diagnoses of FSGS, potentially pointing to secondary or genetic causes of FSGS. However, FSGS is a non-specific lesion, indicative of progressive podocyte loss, a feature of any progressive CKD. The geographical distribution of KRT cases within Aguascalientes may also contribute to pinpoint the cause, as there was a high incidence in certain populations, such as Calvillo (Figure 2B).

WHY IS AGUASCALIENTES DIFFERENT FROM MESOAMERICAN NEPHROPATHY AND SRI LANKA CKDu?

Aguascalientes is a highland, and thus differs from Sri Lanka and classical sites for Mesoamerican nephropathy, which are lowlands and have higher average temperatures (Table 2). Additionally, kidney biopsy reports emphasized the presence of FSGS rather than a predominantly tubulointerstitial and vascular disease. However, the histological descriptions from Aguascalientes, Mesoamerican nephropathy and Sri Lanka CKDu may all be consistent with non-specific CKD findings of glomerular sclerosis, tubular atrophy, interstitial inflammation and vascular injury that may be found in any form of advanced CKD. Thus, in our view, this may not represent a major difference. Centralized analysis of biopsies from these diverse regions by a single pathologist may be desirable.

Table 2.

Features of Aguascalientes nephropathy, Mesoamerican nephropathy and Sri Lanka CKDu

| Feature | Aguascalientes nephropathy | Mesoamerican nephropathy | Sri Lanka CKDu |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at ESKD (years), range | 20–44 | 3–5th decade [20] | Wide age range [20] |

| Sex | Males | Males | Male > female for CKD G3/G4 [20] |

| Climate | Dry, average yearlong temperature 19°C | Humid, average temperature 26°C | Dry [20], average temperature in coast 28°C |

| Altitude | Highland (Aguascalientes 1888 m; Calvillo 1632 m) | Lowland | Lowland |

| Occupation | – | Agricultural | Chena farming [20] |

| Family clustering | – | Yes | – |

| Childhood evidence of disease | – | Yes | – |

| Hypertension | – | Rare | – |

| Proteinuria | – | Minor or non [20] | Minimal [20] |

| Sediment | – | Sterile pyuria [20] | Without clusters [20] |

| Urinary biomarkers | – | NGAL [21–23], KIM-1 [4] | NGAL and KIM-1 [24] |

| Histology | FSGS, interstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy, arteriolar changes predominantly median hyperplasia | Extensive glomerulosclerosis/signs of chronic glomerular ischaemia, chronic tubulointerstitial nephropathy, mild vascular lesions [3, 25] | Glomerular sclerosis/glomerular collapse, interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy, interstitial mononuclear cell infiltration, fibrous intimal thickening and arteriolar hyalinosis [26] |

NGAL: neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin; KIM-1: kidney injury molecule-1.

WHAT MIGHT CAUSE AGUASCALIENTES NEPHROPATHY?

The yet unsolved mystery of one of the hottest CKD hotspots in Mexico should be addressed from different approaches. What clues on potential genetic and/or environmental drivers of CKD in Aguascalientes are currently available?

The age clue

KRT due to Aguascalientes CKDu peaks between the ages of 20 and 40 years. The occurrence of KRT at such a young age may be consistent with genetic predisposition and/or occupational exposures. However, it cannot be discarded that the very same cause was contributing to kidney disease in older patients diagnosed with diabetic kidney disease (a diagnosis usually made in the absence of a kidney biopsy) or with hypertensive nephropathy. The diagnosis of hypertensive nephropathy is one of exclusion, as is usually made in hypertensive individuals with CKDu [27]. Indeed, in US African Americans, so-called hypertensive nephropathy is now widely acknowledged to represent a genetic predisposition to CKD due to APOL1 alleles, which most recently have been linked to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) -associated kidney disease [28]. In this regard, Gutierrez-Peña et al. [18] report a low prevalence of African ancestry in the region.

The FSGS clue

The most frequent kidney biopsy pattern in Aguascalientes was FSGS, which differs from CKDu descriptions from El Salvador, Nicaragua and Sri Lanka (with mainly interstitial involvement). FSGS is classified as a podocytopathy, which may be primary (usually associated to nephrotic syndrome) secondary to several conditions, including loss of kidney mass (hyperfiltration) from any cause, or genetic, the latter two not associated with nephrotic syndrome [29, 30]. Nephrotic syndrome was present in just one-fourth of patients between 21 and 40 years old, placing the focus on the other causes. Patients with hyperfiltration-mediated podocytopathies frequently have FSGS and glomerulomegaly, the latter a finding seen in 62% of patients in this age range in Aguascalientes [18]. In addition to acquired kidney disease, low birth nephron endowment is a cause of reduced kidney mass. Low birthweight and prematurity are frequent causes of low nephron number that are not frequently recorded for adult patients [31].

Regarding genetic causes, type IV collagen (COL4A) gene variants linked to Alport syndrome have recently emerged as the most common (44–56%) cause of genetic FSGS in adults [32]. Variants in other podocyte-expressed genes found in adults with FSGS include ACTN4, TRPC6, INF2, ANLN and NPHS2 [33, 34]. However, there are no data regarding familial history and little is known about the timeline of the high prevalence of CKDu in Aguascalientes over the past decades. Purely genetic causes would not explain a recent surge in CKD cases, unless there was an environment–genetic interaction and the environment changed.

The genetics clue

Beyond the suggestion that FSGS cases may have a genetic component, there are historical records that suggest a high level of inbreeding in Jalisco and Aguascalientes up to the 19th century (83% of all marriages in the 16th century and 75% in the 18th century), including church documents allowing consanguineous marriages, although inbreeding decreased dramatically in the 19th and 20th centuries [35, 36]. This may have facilitated a local prevalence of genetic variants that is higher than expected that either predispose to kidney disease by themselves or predispose to kidney disease under certain environmental conditions. Clustering of cases in small villages that have seen a milder influx of out-of-state persons in recent decades may be a clue in this regard. Gutierrez-Peña et al. [18] report a pilot study that did not find evidence of inbreeding in patients with Aguascalientes CKDu. We are not aware of information on genes predisposing to CKD in the Aguascalientes context. However, we did find an interesting piece of information that merits exploration. A Google search for genetic variants and Aguascalientes identified a methodological manuscript on genetic variants of ATP6V0A2 [36]. The study was triggered by prior reports of two patients in two Aguascalientes locations who were born to consanguineous parents [37]. ATP6V0A2 encodes for the lysosomal H+-transporting ATPase V0 subunit A2. Pathogenic mutations in this gene have been associated with autosomal recessive cutis laxa disease type II-A (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man 219200). While the selection criteria for the studied individuals were not detailed and the number was small (n = 10), the manuscript states that the incidence of the truncating genetic variant c.187C>T (p.Arg63Ter) was 30%, somehow implying that the sample was random. Participants were from Túnel de Potrerillo (population 154), Boca del Túnel (population 100) and Túneles (Rincón de Romos, Aguascalientes) (Figure 2B). According to the gnomAD version 2.1.1 database, this genetic variant was only found in Latino/admixed populations (1 in 11 500) or African/African American populations (1 in 16 200), but not in Europeans or in Asians [38]. Thus, potentially this genetic variant may be common in Aguascalientes. Interestingly, ATP6V0A2 messenger RNA (mRNA) is expressed mainly in podocytes and distal tubules according to single-cell transcriptomics studies, as well as in macrophages [39] (Figure 4A). The Protein Atlas confirmed these data at the protein level (Figure 4B). Regarding kidney disease, single-cell transcriptomics identified ATP6V0A2 mRNA as potentially downregulated in diabetic kidneys in podocytes and increased in infiltrating leucocytes, although the adjusted P-values were not significant [40]. Moreover, in the Nephroseq database of kidney transcriptomics studies, higher expression of ATP6V0A2 mRNA in kidney, glomeruli or tubulointerstitium was associated with decreased estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and proteinuria, i.e. ATP6V0A2 mRNA levels were correlated with the severity of kidney injury in diverse human nephropathies, including FSGS (Table 3). This or other genetic variants not yet associated to kidney disease in the literature may be more prevalent in Aguascalientes than in other regions and underlie the high incidence and prevalence of KTR.

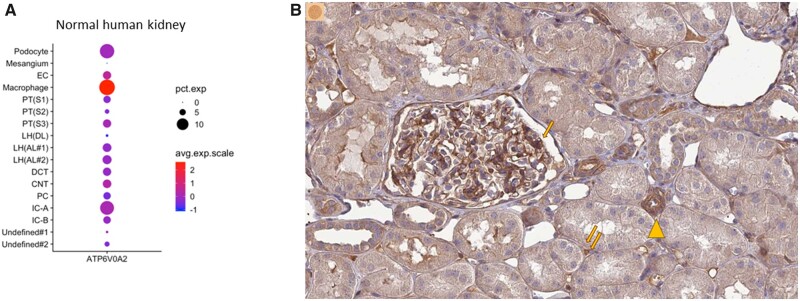

FIGURE 4:

Kidney expression of ATP6V0A2. (A) Single-cell transcriptomics of human kidney tissue identified kidney ATP6V0A2 mRNA expression mainly in podocytes and distal tubules. Sources: [39] and [41]. (B) ATP6V0A2 immunostaining in the kidney. Note the high expression in the glomerular capillary walls, potentially corresponding to podocytes (arrows) and distal tubules (arrowheads) as well as interstitium (double arrow). Image credit: Human Protein Atlas. Image available from version 20.1 at https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000185344-ATP6V0A2/tissue/kidney#img[42] (accessed 20 June 2021).

Table 3.

Analytical correlates of kidney ATP6V0A2 mRNA expression in human kidney disease according to the Nephroseq database of kidney transcriptomics studies [43]

| Sample | Kidney disease or condition | R-value | P-value | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| eGFR | ||||

| Tubulointerstitium | IgA nephropathy | −0.540 | 0.007 | [44] |

| Tubulointerstitium | Lupus nephritis | −0.793 | 0.033 | [45] |

| Glomeruli | Lupus nephritis | −0.706 | 0.034 | [45] |

| Kidney | Transplant kidney | −0.521 | 0.038 | [46] |

| Proteinuria | ||||

| Tubulointerstitium | FSGS | 0.672 | 0.012 | [45] |

| Glomeruli | Collapsing FSGS | 0.963 | 0.037 | [47] |

The environmental clue

Environmental factors have been linked to CKDu. Although these have been mainly associated with tubulointerstitial disease, at this stage we cannot yet exclude that the FSGS lesions observed in Aguascalientes are secondary to decreased kidney mass from other causes.

The municipality with the highest prevalence of KRT is Calvillo, which could be a good starting point. Calvillo is one of the richest counties in Aguascalientes and the largest guava producer in Mexico. Psidium gujava, the guava tree, is considered a medicinal plant and contains several compounds with described medicinal properties, i.e. it contains potentially bioactive molecules [48]. Guava is a widely consumed fruit and its leaves are used to make tea and traditional remedies such as antidiarrhoeals. However, some of the isolated bioactive compounds are cytotoxic [49]. Increased serum urea in male rats and nephrocalcinosis and chronic pyelonephritis in female rats were described in low-quality nephrotoxicity studies [50]. Increased creatinine was also described in mice and rats ingesting guava leaves [51, 52]. Furthermore, guava could be a potential source of heavy metals if the soil and irrigation water are contaminated, as recently reported in South Africa, where the total target hazard quotient values for heavy metals in guava were within unsafe limits for children 53]. Moreover, the issue of overuse or misuse of pesticides for guava farming (Fulidol, Slaughter, Furadan, malathion and parathion among others) leading to ground and water contamination or unsafe direct exposure has been raised as potentially contributing to CKDu in Calvillo [54]. Overexposure to malathion [55, 56] and cypermethrin [57, 58], used as pesticides on guava farms in Calvillo, has also been reported as potentially associated with impaired kidney function and nephrotic syndrome [56]. The guava hypothesis, while far-fetched, cannot be discarded outright. There is precedent for unexpected toxicities of edible fruits. Litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.) is a tropical and subtropical fruit belonging to the genus Litchi in the soapberry family, Sapindaceae. Several episodes of litchi toxicity leading to the deaths of children have been reported and the toxicity was variously attributed to pesticides or to a toxin, methylene cyclopropyl-glycine, found in unripe litchi fruit, that depletes glucose reserves in the body, making it more toxic for undernourished children, in whom it may trigger encephalitis-related deaths [59–61]. If such an acute severe event was not identified until the end of 20th century, more insidious kidney toxicity may be even more difficult to detect.

Contamination of water used for drinking or crop irrigation is another potential concern. Aguascalientes sits just north of Jalisco and both the Calvillo and San Pedro rivers flow into Jalisco. In Calvillo, Gutierrez-Peña et al. [18] report a high proportion (44%) of wells with fluoride levels above the Mexican standard of <1.5 mg/L; although lead, arsenic, aluminium, barium, cadmium, copper, total chromium, iron, manganese, mercury and zinc were within safe limits. Specifically, according to the Department of Sanitary Regulation of the State of Aguascalientes, levels of fluoride were 1.86 ± 1.8 mg/L in Calvillo wells. This raises the issue of potential fluoride toxicity to the kidneys. In mice, intake of water with fluoride levels of 1.5 mg/L synergized with water containing the World Health Organization (WHO) maximum recommended levels for cadmium and hardness to cause kidney injury characterized by interstitial fibrosis, mononuclear cell interstitial infiltration, tubular atrophy and, interestingly, FSGS [62]. Thus the fluoride content in drinking water in Calvillo may theoretically synergize with other components of water or with a genetic predisposition to cause kidney injury. In India, high serum and/or urine fluoride levels were found in 20% of children with nephrotic syndrome [63]. Indeed, foot process effacement, indicative of podocyte injury, was observed in mice exposed to fluoride [64]. Fluoride is the nephrotoxic component in methoxyflurane [65] and high bone fluoride (and lead) were found in Sri Lanka CKDu, although it was unclear to what extent they were caused or a consequence of CKD [66]. However, urinary and serum fluoride were also increased, suggesting increased exposure and potential contribution to nephrotoxicity [67]. Thus fluoride is an obvious candidate nephrotoxic agent to be studied in Aguascalientes CKDu.

Despite current evidence of a safe water supply for other heavy metals in Calvillo, past exposure cannot be discarded as contributing to CKDu. Several occurrences of contaminated water have been described in Aguascalientes. Calvillo sits on the Calvillo riverbank, which runs parallel to the San Pedro River, the main body of water in the state. Both rivers draw water from the same mountain range. Marked deterioration in water quality was found in the San Pedro River as it passed by Aguascalientes in 2011 [68]. In northern Aguascalientes, 42 communities were exposed to high concentrations of arsenic in drinking water. In Tepezala and Asientos, high lead concentrations in blood were observed (>10 µg/dL). The infant populations exposed to metals in drinking water showed a statistically significant correlation between exposure to cadmium or lead and urinary protein; however, the cadmium and lead concentrations in the water supplies were only slightly higher than the levels recommended by the WHO. Heavy contamination of the San Pedro River was linked to the discharge of domestic and industrial effluents with high concentrations of organic matter, nutrients (total phosphorus and total nitrogen), organic xenobiotics and faecal matter. Sediments were high in organic xenobiotics (anilines and detergents), copper and zinc of anthropogenic origin, as well as contamination of natural origin by arsenic. Natural arsenic contamination is likely linked to the volcanic activity and thermal waters that originated the name of Aguascalientes [69]. Groundwater contained high concentrations of fluorides, arsenic, mercury, chromium, iron, manganese and lead. According to the US Environmental Protection Agency criteria, all the sediment samples in one study were polluted by arsenic, 50% by lead and zinc, 25% by copper and ∼13% by manganese and chromium. Three sediment samples presented moderate pollution by iron and another three by mercury. However, wells did not show conclusive evidence of pollution of the aquifer and individual wells duplicated the safe limit for arsenic or mercury in drinking water [70].

Lastly, air pollutants such as 2.5-μm particulate matter are high in Aguascalientes, and these pollutants have been related to low birthweight, a potential cause of CKD [71].

In summary, there is evidence for potential exposure to heavy metals and/or pesticides. Potential interactions and synergy between them in causing nephrotoxicity should be explored. In this regard, exposure may have occurred years before and sources of exposure may already have been corrected. In pre-clinical studies, maternal exposure to excess fluoride may cause nephrotoxicity in offspring that becomes evident during puberty [64] and bone accumulation of lead and fluoride in persons may cause a slow release from endogenous sources and nephrotoxicity [66].

WHAT ARE THE NEXT STEPS?

According to the GBD 2017 Study, the age-standardized CKD mortality in Aguascalientes is below the national average [8]. This should be corrected in light of the evidence presented by Gutierrez-Peña et al. [18]. Furthermore, given the extremely high incidence of KRT in young people, understanding the cause of Aguascalientes CKDu should be viewed as a research priority to which international funders of health research should contribute. Several potentially interacting genetic and environmental factors have been identified. Unravelling their contributions to CKD in Aguascalientes may benefit CKD patients throughout the world. The need for urgent action to identify and stem the cause of the high incidence of CKD extends to other CKD hotspots in Mexico, including Tierra Blanca in Veracruz and Poncitlan in Jalisco. Table 4 presents a draft research agenda.

Table 4.

Potential research agenda to unravel the drivers of CKDu in Aguascalientes

|

Stage 1. Basic epidemiology

|

FUNDING

This study was supported by FIS/Fondos FEDER (PI18/01366, PI19/00588, PI19/00815 and DTS18/00032), ERA-PerMed-JTC2018 (KIDNEY ATTACK AC18/00064 and PERSTIGAN AC18/00071, ISCIII-RETIC REDinREN RD016/0009) and Sociedad Española de Nefrología, FRIAT, Comunidad de Madrid en Biomedicina B2017/BMD-3686 CIFRA2-CM.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

A.O. has received consultancy or speaker fees or travel support from Astellas, AstraZeneca, Amicus, Amgen, Fresenius Medical Care, Bayer, Sanofi-Genzyme, Menarini, Kyowa Kirin, Alexion, Otsuka and Vifor Fresenius Medical Care Renal Pharma and is Director of the Catedra Mundipharma-UAM of diabetic kidney disease and the Catedra Astrazeneca-UAM of CKD and electrolytes. A.O. is Editor-in-Chief of Clinical Kidney Journal.

Contributor Information

Priscila Villalvazo, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain.

Sol Carriazo, IIS-Fundacion Jimenez Diaz UAM and School of Medicine, UAM, Madrid, Spain.

Catalina Martin-Cleary, IIS-Fundacion Jimenez Diaz UAM and School of Medicine, UAM, Madrid, Spain.

Alberto Ortiz, IIS-Fundacion Jimenez Diaz UAM and School of Medicine, UAM, Madrid, Spain.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ferguson R, Leatherman S, Fiore Met al. Prevalence and risk factors for CKD in the general population of southwestern Nicaragua. J Am Soc Nephrol 2020; 31: 1585–1593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chandrajith R, Nanayakkara S, Itai Ket al. Chronic kidney diseases of uncertain etiology (CKDue) in Sri Lanka: geographic distribution and environmental implications. Environ Geochem Health 2011; 33: 267–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wijkström J, Leiva R, Elinder CGet al. Clinical and pathological characterization of mesoamerican nephropathy: a new kidney disease in Central America. Am J Kidney Dis 2013; 62: 908–918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Leibler JH, Ramirez-Rubio O, Velázquez JJAet al. Biomarkers of kidney injury among children in a high-risk region for chronic kidney disease of uncertain etiology. Pediatr Nephrol 2021; 36: 387–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. González-Quiroz M, Pearce N, Caplin Bet al. What do epidemiological studies tell us about chronic kidney disease of undetermined cause in Meso-America? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Kidney J 2018; 11: 496–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Perez-Gomez MV, Martin-Cleary C, Fernandez-Fernandez Bet al. Meso-American nephropathy: what we have learned about the potential genetic influence on chronic kidney disease development. Clin Kidney J 2018; 11: 491–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. GBD Compare | IHME Viz Hub. https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/ (16 April 2021, date last accessed)

- 8. Agudelo-Botero M, Valdez-Ortiz R, Giraldo-Rodríguez Let al. Overview of the burden of chronic kidney disease in Mexico: secondary data analysis based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. BMJ Open 2020; 10: e035285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Boletin Estadistico Informativo del Centro Nacional de Trasplantes (BEI-CENATRA) Volumen V, No. 1, Periodo: Enero-junio, 2020. https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/590075/BEI-CENATRA_03-11-2020.pdf (14 April 2021, date last accessed)

- 10. INEGI. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Censo Población y Vivienda2020. https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2020/default.html#Documentacion (20 April 2021, date last accessed)

- 11. Méndez-Durán A, Francisco Méndez-Bueno J, Tapia-Yáñez Tet al. Epidemiología de la insuficiencia renal crónica en México. Dial Trasplante 2010; 31: 7–11 [Google Scholar]

- 12. United Stated Renal Data System (USRDS). USRDS Home Page. https://www.usrds.org/ (16 April 2021, date last accessed)

- 13. Obrador GT, García-García G, Villa ARet al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP) México and comparison with KEEP US. Kidney Int 2010; 77: S2–S8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Centro Nacional de Trasplantes. Estado Actual de Donación y Trasplantes en México Anual2013. http://www.gob.mx/cenatra/documentos/estadisticas-50060 (28 January 2017, date last accessed)

- 15. De Arrigunaga SA, Martinez MAC, Ortega Cet al. Clinical and pathological characterization of patients with ESKD from a potential Mexican CKD of undetermined etiology (CKDu) hotspot. J Am Soc Nephrol 2019; 30: 220 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Correa-Rotter R. Report From the Third International Workshop on Chronic Kidney Diseases of Uncertain/Non-Traditional Etiology in Mesoamerica and Other Regions Workshop Organizing Committee: Technical Series SALTRA. NIEHS. www.saltra.una.ac.cr (16 April 2021, date last accessed)

- 17. File:Mexico States blank map.svg - Wikipedia. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Mexico_States_blank_map.svg (22 June 2021, date last accessed)

- 18. Gutierrez-Peña M, Zuñiga-Macias L, Marin-Garcia Ret al. High prevalence of end-stage renal disease of unknown origin in Aguascalientes Mexico: role of the registry of chronic kidney disease and renal biopsy in its approach and future directions. Clin Kidney J 2021; 14: 1197–1206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. United Stated Renal Data System. End-stage Renal Disease, International Comparisons. https://adr.usrds.org/2020/end-stage-renal-disease/11-international-comparisons (16 April 2021, date last accessed)

- 20. Weaver VM, Fadrowski JJ, Jaar BG.. Global dimensions of chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology (CKDu): a modern era environmental and/or occupational nephropathy? BMC Nephrol 2015; 16: 145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. González-Quiroz M, Camacho A, Faber Det al. Rationale, description and baseline findings of a community-based prospective cohort study of kidney function amongst the young rural population of northwest Nicaragua. BMC Nephrol 2017; 18: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gonzalez-Quiroz M, Smpokou ET, Silverwood RJet al. Decline in kidney function among apparently healthy young adults at risk of Mesoamerican nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 2018; 29: 2200–2212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Laws RL, Brooks DR, Amador JJet al. Biomarkers of kidney injury among Nicaraguan sugarcane workers. Am J Kidney Dis 2016; 67: 209–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gunasekara T, De Silva PMCS, Herath Cet al. The utility of novel renal biomarkers in assessment of chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology (CKDu): a review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17: 9522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. López-Marín L, Chávez Y, García XAet al. Histopathology of chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology in Salvadoran agricultural communities. MEDICC Rev 2014; 16: 49–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nanayakkara S, Komiya T, Ratnatunga Net al. Tubulointerstitial damage as the major pathological lesion in endemic chronic kidney disease among farmers in North Central Province of Sri Lanka. Environ Health Prev Med 2012; 17: 213–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Carriazo S, Perez-Gomez MV, Ortiz A.. Hypertensive nephropathy: a major roadblock hindering the advance of precision nephrology. Clin Kidney J 2020; 13: 504–509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Couturier A, Ferlicot S, Chevalier Ket al. Indirect effects of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 on the kidney in coronavirus disease patients. Clin Kidney J 2020; 13: 347–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sethi S, Zand L, Nasr SHet al. Focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis: clinical and kidney biopsy correlations. Clin Kidney J 2014; 7: 531–537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lepori N, Zand L, Sethi Set al. Clinical and pathological phenotype of genetic causes of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in adults. Clin Kidney J 2018; 11: 179–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Conti G, De Vivo D, Fede Cet al. Low birth weight is a conditioning factor for podocyte alteration and steroid dependance in children with nephrotic syndrome. J Nephrol 2018; 31: 411–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Riedhammer KM, Braunisch MC, Günthner Ret al. Exome sequencing and identification of phenocopies in patients with clinically presumed hereditary nephropathies. Am J Kidney Dis 2020; 76: 460–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kopp JB, Anders HJ, Susztak Ket al. Podocytopathies. Nat Rev Dis Prim 2020; 6: 1–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ahn W, Bomback AS.. Approach to diagnosis and management of primary glomerular diseases due to podocytopathies in adults: core curriculum 2020. Am J Kidney Dis 2020; 75: 955–964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Franco CPT. Matrimonio entre parientes. Causas y causales de dispensa en la parroquia de La Encarnación, 1778–1822. Let Hist 2015; 13: 59–85 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Esparza VMG. La erosión de la endogamia o de la dinámica del mestizaje. Aguascalientes, Nueva Galicia, siglos XVII y XVIII. Relac Estud Hist Soc 2019; 40: 148–177 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bahena-Bahena D, López-Valdez J, Raymond Ket al. ATP6V0A2 mutations present in two Mexican Mestizo children with an autosomal recessive cutis laxa syndrome type IIA. Mol Genet Metab Rep 2014; 1: 203–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. 12-124203239-C-T | gnomAD v2.1.1 | gnomAD. https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/variant/12-124203239-C-T?dataset=gnomad_r2_1 (21 June 2021, date last accessed)

- 39. Wu H, Uchimura K, Donnelly ELet al. Comparative analysis and refinement of human PSC-derived kidney organoid differentiation with single-cell transcriptomics. Cell Stem Cell 2018; 23: 869–881e8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wilson PC, Wu H, Kirita Yet al. The single-cell transcriptomic landscape of early human diabetic nephropathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2019; 116: 19619–19625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kidney Interactive Transcriptomics. http://humphreyslab.com/SingleCell/displaycharts.php (21 June 2021, date last accessed)

- 42. Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BMet al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 2015; 347: 1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nephroseq. https://www.nephroseq.org/resource/login.html (21 June 2021, date last accessed)

- 44. Reich HN, Tritchler D, Cattran DCet al. A molecular signature of proteinuria in glomerulonephritis. PLoS One 2010; 5: e13451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cohen CD, Frach K, Schlöndorff D, Kretzler M.. Quantitative gene expression analysis in renal biopsies: a novel protocol for a high-throughput multicenter application. Kidney Int 2002; 61: 133–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Flechner SM, Kurian SM, Solez Ket al. De novo kidney transplantation without use of calcineurin inhibitors preserves renal structure and function at two years. Am J Transplant 2004; 4: 1776–1785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hodgin JB, Borczuk AC, Nasr SHet al. A molecular profile of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. Am J Pathol 2010; 177: 1674–1686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gutiérrez RMP, Mitchell S, Solis RV.. Psidium guajava: a review of its traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology. J Ethnopharmacol 2008; 117: 1–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Feng XH, Wang ZH, Meng DLet al. Cytotoxic and antioxidant constituents from the leaves of Psidium guajava. Bioorganic Med Chem Lett 2015; 25: 2193–2198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Attawish A, Chavalittumrong P, Rugsamon Pet al. Toxicity study of Psidium guajava Linn. leaves 1995. Warasan Krom Witthayasat Ka Phaet 2005; 37: 289–305 [Google Scholar]

- 51. Adeyemi OS, Akanji MA.. Biochemical changes in the kidney and liver of rats following administration of ethanolic extract of Psidium guajava leaves. Hum Exp Toxicol 2011; 30: 1266–1274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Díaz-de-Cerio E, Verardo V, Gómez-Caravaca AMet al. Health effects of Psidium guajava L. leaves: an overview of the last decade. Int J Mol Sci 2017; 18: 897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gupta SK, Ansari FA, Nasr Met al. Multivariate analysis and health risk assessment of heavy metal contents in foodstuffs of Durban, South Africa. Environ Monit Assess 2018; 190: 151–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cardona JHA, Violante RE, Vazquez JRet al. The ingestion of contaminated water with pesticides and heavy metals as probable cause to chronic renal failure. Int J Pure App Biosci 2015; 3: 423–426 [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wan E, Darssan D, Karatela Set al. Association of pesticides and kidney function among adults in the US population. https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-452983/v1 (4 July 2021, date last accessed) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yokota K, Fukuda M, Katafuchi R, Okamoto T.. Nephrotic syndrome and acute kidney injury induced by malathion toxicity. BMJ Case Rep 2017; 2017: bcr201722073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Inayat Q, Ilahi M, Khan J.. A morphometric and histological study of the kidney of mice after dermal application of cypermethrin. J Pak Med Assoc 2007; 57: 587–591 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Haque SM, Sarkar CC, Khatun Set al. Toxic effects of agro-pesticide cypermethrin on histological changes of kidney in Tengra, Mystus tengara. Asian J Med Biol Res 2018; 3: 494–498 [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sinha SN, Ramakrishna UV, Sinha PKet al. A recurring disease outbreak following litchi fruit consumption among children in Muzaffarpur, Bihar–a comprehensive investigation on factors of toxicity. PLoS One 2020; 15: e0244798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Shrivastava A, Kumar A, Thomas JDet al. Association of acute toxic encephalopathy with litchi consumption in an outbreak in Muzaffarpur, India, 2014: a case-control study. Lancet Glob Heal 2017; 5: e458–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Vaux DL, Silke J.. IAPs, RINGs and ubiquitylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2005; 6: 287–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wasana HMS, Perera GDRK, Gunawardena PDSet al. WHO water quality standards vs synergic effect(s) of fluoride, heavy metals and hardness in drinking water on kidney tissues. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 42516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Curnutte JT, Babior BM, Karnovsky ML.. Fluoride-mediated activation of the respiratory burst in human neutrophils. A reversible process. J Clin Invest 1979; 63: 637–647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Tian X, Xie J, Chen Xet al. Deregulation of autophagy is involved in nephrotoxicity of arsenite and fluoride exposure during gestation to puberty in rat offspring. Arch Toxicol 2020; 94: 749–760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Allison SJ, Docherty PD, Pons Det al. Methoxyflurane toxicity: historical determination and lessons for modern patient and occupational exposure. N Z Med J 2021; 134: 76–79 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ananda Jayalal T, Mahawithanage S, Senanayaka Set al. Evidence of selected nephrotoxic elements in Sri Lankan human autopsy bone samples of patients with CKDu and controls. BMC Nephrol 2020; 21: 384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Fernando WBNT, Nanayakkara N, Gunarathne Let al. Serum and urine fluoride levels in populations of high environmental fluoride exposure with endemic CKDu: a case–control study from Sri Lanka. Environ Geochem Health 2020; 42: 1497–1504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Avelar-González FJ, Ramírez LE, Martínez SMet al. Water quality in the State of Aguascalientes and its effects on the population’s health. In: Úrsula Oswald Spring, ed. Water Resources in Mexico: Scarcity, Degradation, Stress, Conflicts, Management, and Policy. Berlin: Springer, 2011, pp. 217–229 [Google Scholar]

- 69. University of Maine. Arsenic. Where Arsenic Comes From. https://umaine.edu/arsenic/where-arsenic-comes-from/ (21 June 2021, date last accessed)

- 70. Guzmán-Colis G, Ramírez-López EM, Thalasso Fet al. Evaluation of pollutants in water and sediments of the San Pedro river in the state of Aguascalientes. Univ Cienc 2011; 27: 17–32 [Google Scholar]

- 71. Secretaría de Sustentabilidad, Medio Ambiente y Agua (SSMAA). Programa Cielo Claro para la Mejora en la Calidad del Aire del Estado de Aguascalientes2018. –2028. https://www.aguascalientes.gob.mx/SSMAA/pdf/ProgramaCieloClaroProAireAguascalientes201820281eraEdicion29nov18.pdf (4 July 2021, date last accessed)