Abstract

Chronic stress during pregnancy harms both the mother and developing child, and there is an urgent unmet need to understand this process in order to develop protective treatments. Here, we report that chronic gestational stress (CGS) causes aberrant maternal care behavior in the form of increased licking and grooming, decreased nursing, and increased time spent nest building. Treatment of CGS-exposed dams with the NAD+-stabilizing agent P7C3-A20 during pregnancy and postpartum, however, preserved normal maternal care behavior. CGS also caused abnormally low weight gain during gestation and postpartum, which was partially ameliorated by maternal treatment with P7C3-A20. Dams also displayed hyperactive locomotion after CGS, which was not affected by P7C3-A20. Although dams did not display a classic depressive-like phenotype after CGS, some changes in anxiety- and depressive-like behaviors were observed. Our results highlight the need for further characterization of the effects of chronic gestational stress on maternal care behavior and provide clues to possible protective mechanisms.

Keywords: Maternal care, prenatal stress, perinatal behavior, drug development, chronic stress

INTRODUCTION

Prenatal stress can confer profound consequences on both mother and child. For example, chronic gestational stress (CGS) impairs maternal care [1, 2], which in turns disrupts normal offspring development [3, 4]. Indeed, aberrant maternal care in both rodents and nonhuman primates leads to higher reactivity to negative stimuli and fear in adult offspring [5, 6]. Notably, some disrupted maternal care behaviors can also be transmitted forward to future generations [7, 8]. This further underscores the urgent need to understand the relationship between maternal stress and impaired maternal care, in order to develop protective treatments.

While many currently available antidepressant medications effectively treat the sequela of chronic stress, they also frequently carry their own independent risks to offspring health and neurodevelopment [9, 10]. As a result, many patients avoid antidepressant medications during pregnancy. Unfortunately, antidepressant cessation is associated with about a 70% relapse into depression during pregnancy, which poses additional risks to the mother and developing baby [11, 12]. We have recently reported that maternal treatment with the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)-stabilizing P7C3 series of compounds, which have shown protective efficacy in models of stress and depression [13–19], rescues the developing embryonic brain from deleterious effects of CGS in mice [20]. Here, we have now examined maternal behavior in this same model, and observed a range of effects. With respect to maternal care behavior, we observed that CGS caused increased licking and grooming, decreased nursing, and increased time spent nest building. Notably, these aberrant maternal care behaviors were prevented by oral treatment of the mother throughout CGS and post-partum with P7C3-A20. We also observed CGS-induced elevated maternal locomotor behavior and reduced maternal weight during gestation and after birth, as well as components of depression- and anxiety-like behavior, which were not completely rescued by maternal P7C3-A20 administration.

METHODS

CD1 mice were divided into four groups: 1) control + vehicle (Ctrl-Veh), 2) control + P7C3-A20 (Ctrl-P7C3), 3) stressed + vehicle (CGS-Veh), and 4) stressed + P7C3-A20 (CGS-P7C3). Mice were housed in cages on a 12h light/dark cycle with ad lib access to food and water. Gestational day 0 (GD0) was identified by visualization of vaginal plug. CGS dams were singly housed from GD0 onward, and Ctrl dams were cohoused. From GD5-GD18, dams were subjected to three 45-minute sessions of restraint stress three times daily (at approximately 0900, 1200, and 1500), according to established methods [21–23]. Briefly, dams were placed in a Plexiglas restraint tube under a bright light. To ensure that only psychosocial stress was induced in dams, the restraints used were designed for rats, and were therefore large enough to accommodate the growing abdomen of pregnant dams without adding mechanical pressure or causing difficulty in respiration. Additionally, a 60-watt equivalent fluorescent light bulb was used to prevent heat stress. P7C3-A20 (10mg/kg twice daily) or vehicle were administered to moms via oral gavage from GD5 until weaning of offspring (postnatal day 21 (P21)).

Behavioral assays

Dams were assessed in the open field test (OFT), elevated plus maze (EPM), and tail suspension test (TST) on GD17. A separate group of dams on P7 was assessed in the same behavioral assays, as well as the forced swim test (FST). Detailed descriptions of behavioral assays can be found in Supplementary Methods. All behavioral tests at each time point were performed during the light cycle on a single day with an initial 30-min acclimation to the testing room and at least one hour between tests.

Maternal care monitoring

Maternal care behavior scoring was performed based on previous work [1, 6, 24, 25]. On the evening of GD19, dams were transferred to a separate housing room for maternal care monitoring. Upon birth, litters were each culled to 8 pups (approximately 4 male, 4 female) to control for rearing differences due to litter size or composition. The maternal care behavior of each dam was videorecorded for eight 60-minute observation periods daily for the first six days postpartum using Reolink (New Castle, Delaware) 8CH Super HD 4.0MP Network Video Recorder cameras. Observations were performed at five periods during the light phase (0500, 0700, 1100, 1300, 1500) and three periods during the dark phase (2000, 2300, 0200). Each videorecorded period was then scored by a single experimenter every four minutes in “snapshots” (15 observations per period × 8 periods per day = 120 observations per mother per day) for the following behaviors: mother on nest, mother off nest, mother licking and grooming any pup, mother eating or drinking, mother building nest, and mother nursing pups. Behavioral categories were not mutually exclusive. For example, licking and grooming often occurred while the mother was on the nest and nursing the pups. Scoring of videos was performed blind to the treatment group of the animals.

Analyses

Graphpad Prism (San Diego, California) software was used to perform all statistical analyses. To evaluate for any effect of CGS at baseline, an a priori two-tailed t-test was performed between Ctrl-Veh and CGS-Veh groups for each measure. For data shown in figures 1 and 2, two-way ANOVAs were also used to assess main effects of CGS and P7C3-A20 treatment across all four groups. For data shown in Figure 3, 3-way ANOVAs were used to assess CGS, P7C3-A20 treatment, and time of day. If an ANOVA main effect of CGS was found, a priori t-test results were not listed for simplicity. For all data, Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests were used for post-hoc pairwise comparisons. Rescue or alleviation of an effect of CGS by P7C3-A20 was defined as the presence of a statistically significant difference between the CGS-Veh and both the Ctrl-Veh and CGS-P7C3-A20 groups. Partial rescue was defined as a statistically significant difference between the CGS-Veh and Ctrl-Veh groups only via either a priori t-test or post-hoc multiple comparisons, with no significant difference between the Ctrl-Veh group and CGS-P7C3-A20 group.

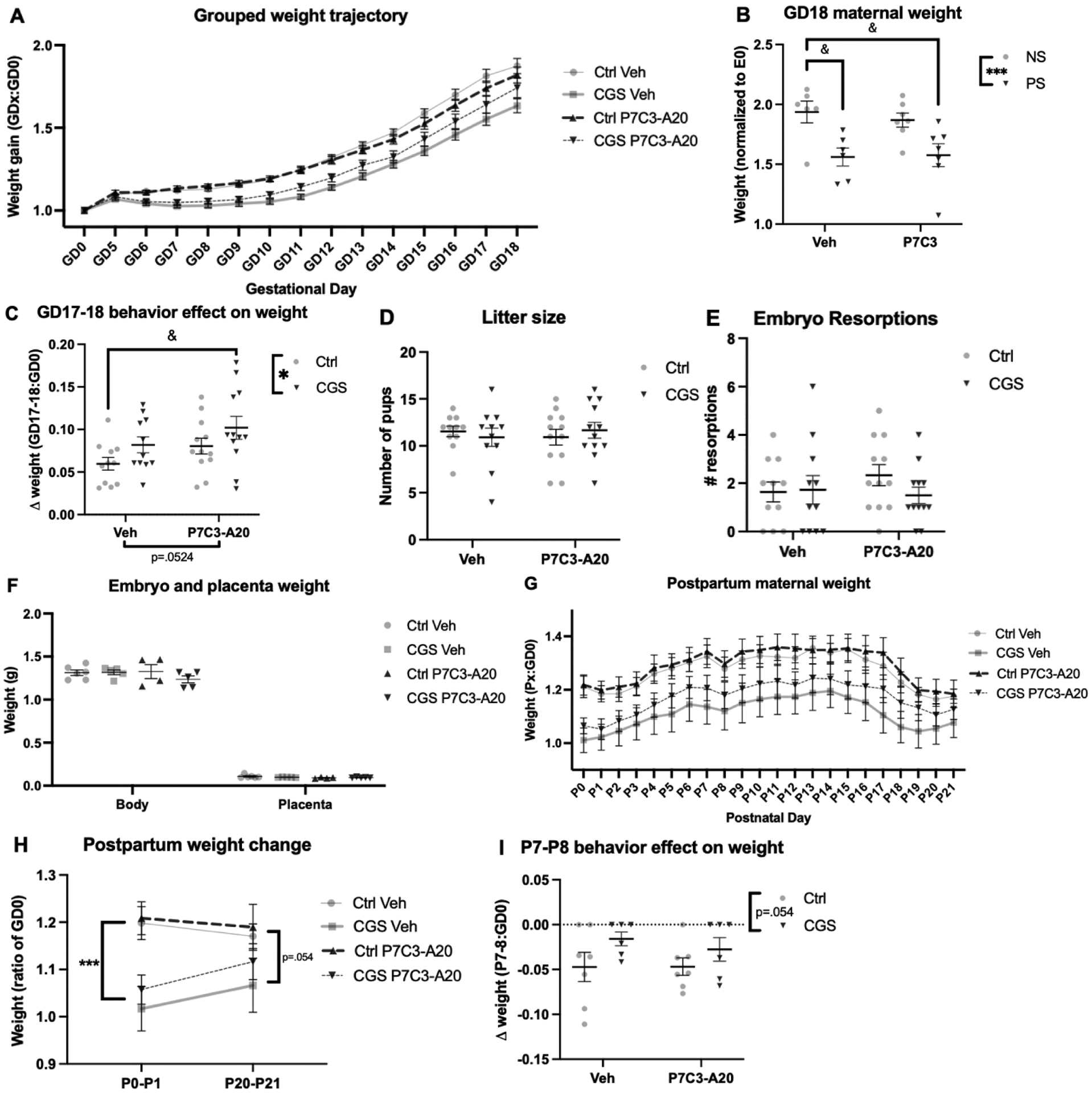

Figure 1: Dam weight during gestation and postpartum was affected by CGS, but litter size, pup weight, and placenta weight were not impacted.

A) Weight trajectory of dams during gestation. B) Final dam weight on the day before birth, GD18, was significantly reduced by CGS and partially rescued by P7C3-A20 treatment (main effect of CGS, **p=0.0029; Ctrl-Veh vs. CGS-Veh &&p=.0099). C) Both CGS and P7C3-A20 treatment protected from behavioral testing-induced slowing of weight gain at the end of pregnancy (main effect of CGS, *p=.0389; Ctrl-Veh vs. CGS-P7C3 &p=.0277). D-F) Litter size, number of embryo resorptions, and embryo and placental weight at GD18 were not affected by CGS or P7C3-A20 treatment (n.s.). G) Weight trajectory of dams after birth (P0) until pups were weaned (P21). H) Immediately following birth, CGS dams weighed significantly less than Ctrl dams (***p=.0002). At P21, CGS dams remained slightly lighter than Ctrl dams (trend, p=0.0541). I) On P8, the day after behavior testing, less weight was lost in CGS dams than Ctrl dams (trend, p=0.0539).

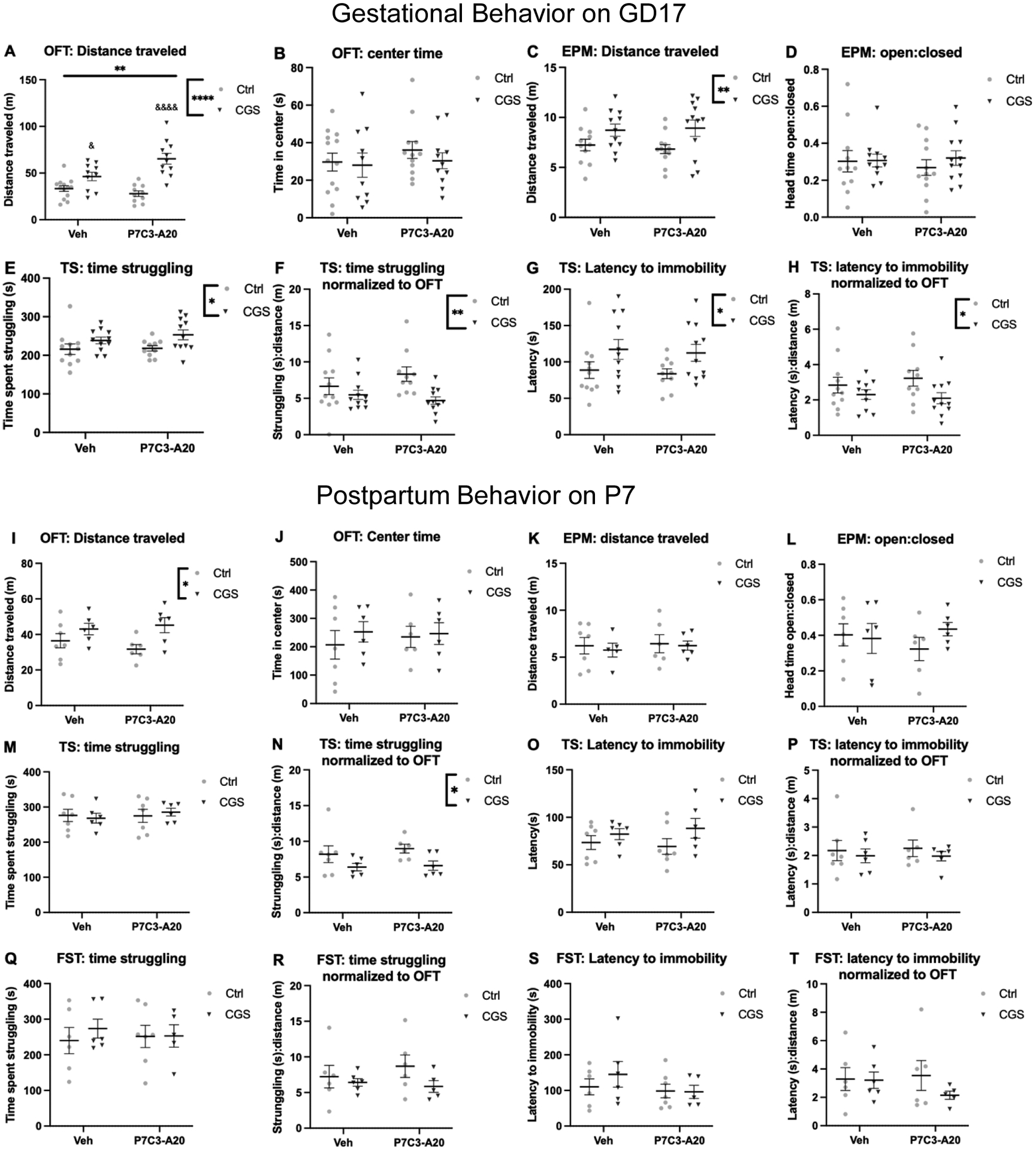

Figure 2: Dam behavior is affected by CGS during gestation and postpartum.

A-H: Gestational behavior at GD17. A) CGS increased locomotor activity (main effect of CGS, ****p<.0001; interaction, **p=.0065; Ctrl-P7C3 vs. CGS-P7C3 &&&&p<.0001, CGS-Veh vs. Ctrl-P7C3 &p=.0264, CGS-Veh vs. CGS-P7C3 &p=.0179, and Ctrl-P7C3 vs. CGS-P7C3 &&&&p<.0001), but not center time during the habituation period (B, n.s.). C) Locomotor activity was increased by CGS (**p= .0071), but not open:closed head time (D, n.s.). E) Time struggling was increased by CGS (*p=.0128). F) Normalized time struggling was decreased by CGS (**p=.0079). G) Latency to immobility was increased by CGS (*p=.0157). H) Normalized latency to immobility was decreased by CGS (*p=.0342). I-T: Postpartum behavior at P7. I) CGS increased locomotor activity (*p=0.0112), but not center time (J, n.s.). K-L) No effect of CGS or P7C3-A20 on locomotor activity or open:closed head time. M) No effect on time spent struggling, but CGS decreased normalized struggle time (N, *p=.0193). O-T) Struggle time in the FST and latency to immobility in the TS and FST were not different between groups whether measured at baseline or normalized.

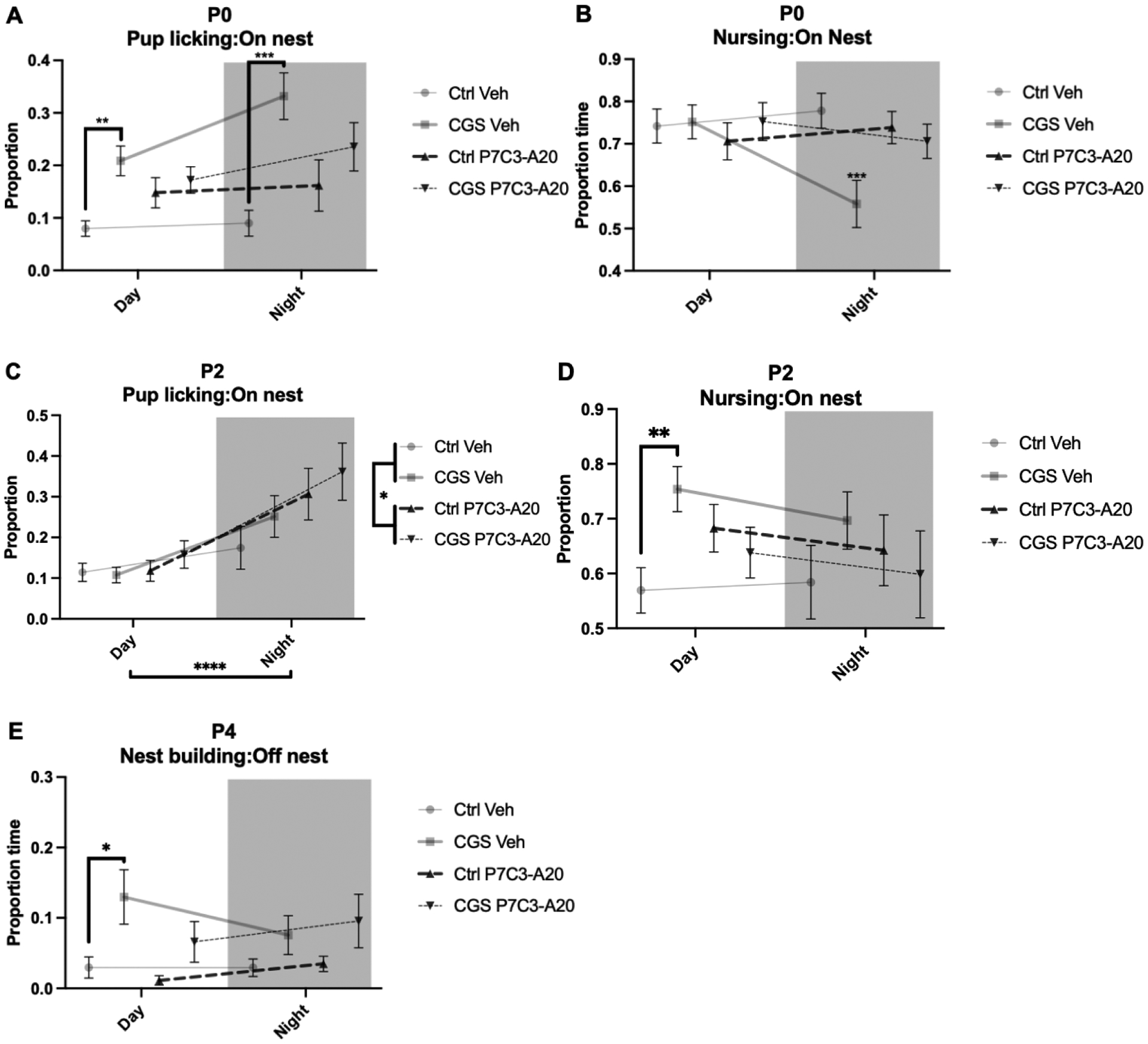

Figure 3: Dam maternal care behaviors were changed by CGS and ameliorated by P7C3-A20 administration.

A) On P0, CGS increased pup licking while on the nest during the day (**p=.0014) and at night (***p=.0004). B) On P0, CGS decreased pup nursing while on the nest at night (***p<.0001). C) On P2, all groups upregulated pup licking at night (****p<.0001) and P7C3-A20 treatment additionally increased pup licking (*p=.0283). D) On P2, CGS increased pup nursing while on the nest during the day (**p=.0094). E) On P4, CGS dams spent more time nest building while off the nest during the day than control dams (p=.0361).

RESULTS

Chronic gestational stress affects dam weight gain during gestation and postpartum, but not litter size

During pregnancy, CGS reduced dam weight gain, which was partially rescued by P7C3-A20 treatment (Fig. 1A, B, FCGS[1,42]=9.980, p=0.0029; Ctrl-Veh vs. CGS-Veh p=.0099, Ctrl-Veh vs. CGS-P7C3 p=.2664 [n.s.], post-hoc). Behavioral testing on GD17 was also associated with reduced dam weight gain from GD17 to GD18 (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, CGS blocked this effect, P7C3-A20 treatment showed a similar trend, and CGS and P7C3-A20 together showed an additive protective effect (Fig. 1C, FCGS[1,42]=4.543, p=.0389; FP7C3-A20[1,42]=3.985, p=.0524; Ctrl-Veh vs. CGS-P7C3 p=.0277, post-hoc). Effects on weight were specific to the dam, as litter size, number of embryo resorptions, and embryo and placental weight at GD18 were not affected by CGS or P7C3-A20 treatment (Fig. 1D–F).

CGS also altered postpartum dam weight trajectory (Fig. 1G). While CGS dams weighed significantly less than Ctrl dams immediately following birth (Fig. 1H, FCGS[1,22]=19.92, p=.0002), weight in all four groups steadily converged thereafter with CGS dams trending lighter than Ctrl dams (FCGS[1,22]=4.139, p=0.0541). The postpartum effects of CGS on weight gain were not alleviated by P7C3-A20 treatment, which continued through P21. Similar to the effect of behavioral testing on weight gain during gestation, dams showed decreased weight on postnatal day 8 (P8), the day after P7 behavior testing, and CGS dams showed a trend of less weight loss with this manipulation than Ctrl dams (Fig. 1I, trend, FCGS[1,22]=4.147, p=0.0539).

Maternal stress increases locomotor activity during pregnancy and postpartum, and alters affective-like behaviors during pregnancy

Because chronic stress can lead to anxiety-like and depressive-like phenotypes, we measured related behaviors in dams during pregnancy and postpartum. On GD17, neither CGS nor P7C3-A20 affected anxiety-like measures in the OFT or EPM (Fig. 2B, D). However, CGS significantly increased locomotor activity in both tests, an effect not prevented by treatment with P7C3-A20. (Fig. 2A, C, OFT: FCGS[1,40]=35.24, p<.0001; Finteraction[1,40]=8.243, p=.0065; Ctrl-Veh vs. CGS-Veh p=.1380 [n.s.], Ctrl-P7C3 vs. CGS-P7C3 p<.0001, CGS-Veh vs. CGS-P7C3 p=.0179, post-hoc; EPM: FCGS[1, 42] = 8.016, **p.0071). Interestingly, in the TST, CGS increased the time spent struggling (Fig. 2E, FCGS[1, 39] = 6.809, p=.0128) and latency to immobility (Fig. 2G, FCGS[1, 39] = 6.377, p=.0157). To determine whether higher locomotor activity after CGS, as shown in the OFT and EPM, might be related to this apparent anti-depressive like behavior, we normalized TST measures to each animal’s baseline activity (distance traveled in OFT). With baseline activity taken into account to establish a normalized data set, CGS decreased the time dams spent struggling (FCGS[1,39]= 7.847, p=.0079, Fig. 2F) and their latency to immobility (FCGS[1, 38] = 4.827, p=.0342 Fig. 2H), compatible with increased depressive-like behavior. In either normalized or non-normalized data sets, P7C3-A20 treatment had no effect.

On P7, CGS also increased maternal locomotor activity in the OFT, irrespective of P7C3-A20 treatment (Fig. 2I, FCGS[1, 21] = 7.740, p=0.0112). Paradoxically, locomotor behavior was not increased in the EPM task (Fig. 2K). No anxiety-like behavior was observed after CGS in the OFT or EPM (Fig. 2J, L), similar to findings on GD17. The total immobile time on the FST and TST did not differ significantly between groups (Fig. 2M, O). However, when normalized to OFT activity level, there was a main effect of CGS on struggling in the TST, such that CGS dams showed a depressive-like phenotype (Fig. 2N), similar to the effect on GD17. This effect was not altered by P7C3-A20 and was not present on the FST (Fig. 2P). Unlike findings on GD17, latency to immobility did not differ between groups on the TST or FST before or after normalization to baseline activity (Fig. 2Q–T).

Chronic gestational stress alters maternal care, an effect ameliorated by P7C3-A20 treatment

Because CGS may impact maternal care, we monitored maternal care behaviors during the first postnatal week, according to established methods [1, 6, 24, 25]. We additionally examined whether treatment with P7C3-A20 would rescue any CGS-induced changes in maternal care behaviors, as we recently showed that this treatment protects the developing embryo from the acute and chronic effects of CGS [20]. Dams were video recorded in their home cages from P0-P6 and then scored for time spent on the nest, off the nest, licking and grooming pups, eating or drinking, nest building, and nursing pups. CGS aberrantly increased licking and grooming of pups while on the nest during both light and dark cycles on P0 (Fig. 3A, FCGS[1,44]=23.35, p<.0001; a priori two-tailed t-test, Ctrl-Veh vs. CGS-Veh Day, t=4.235, df=11, p=.0014; Ctrl-Veh vs. CGS-Veh Night, t=4.973, df=11, p=.0004), and this effect was partially mitigated by maternal P7C3-A20 treatment (Fig. 3A, Ctrl-Veh vs. CGS-P7C3 Day: n.s.; Ctrl-Veh vs. CGS-P7C3 Night: n.s., post-hoc). CGS also decreased the time spent nursing during the dark phase on P0, which was also rescued by maternal P7C3-A20 treatment (Fig. 3B, p<.0001 for CGS-Veh vs. all other groups, post-hoc). On P2, time spent licking and grooming pups while on the nest was not affected by CGS, but P7C3-A20 treated dams of Ctrl and CGS combined spent slightly more time licking and grooming pups than vehicle-treated dams, and all dams spent more time licking and grooming during the dark phase (Fig. 3C, Fday/night[1,44]=20.83, p<.0001; FP7C3-A20[1,44]=5.146, p=.0283). Also on P2, CGS dams spent more time on the nest nursing during the light phase (Fig. 3D, a priori two-tailed t-test, t=3.142, df=11, p=.0094), which was partially rescued by P7C3-A20 treatment (Fig. 3D, Ctrl-Veh vs. CGS-P7C3 Day: n.s.; Ctrl-Veh vs. CGS-P7C3 Night: n.s., Fig. 3D, post-hoc). No differences between groups were observed for pup licking or nursing while on the nest on P4 or P6 (Supplementary Fig. S1).

On P0 and P2, there were no differences in time spent nest building between groups (Supplementary Fig. 2A, B). On P4, CGS dams spent more time nest building while off the nest (Fig. 3E, FCGS[1,42]=13.08, p=.0008). Specifically, CGS dams spent more time nest building during the light phase, which was partially ameliorated by P7C3-A20 treatment (Fig. 3E, a priori t-test, t=2.420, df=10, p=.0361; Ctrl-Veh vs. CGS-P7C3-A20, p=.9587, n.s., post-hoc). Dams of all conditions spent less time on the nest during the dark phase (Supplementary Fig. S3).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that maternal care behaviors were impacted by CGS, all of which were at least partially rescued by P7C3-A20 treatment (Fig. 4A-D). Other studies show some support for antidepressant agents, such as fluoxetine, in also rescuing altered maternal care behaviors [26, 27]. Given its previous efficacy in ameliorating depression-like behavior [13, 14], we hypothesized, and subsequently observed, that in this model P7C3-A20 can rescue CGS-induced changes in maternal care behaviors. However, how antidepressants may affect maternal care both with and without CGS remains unclear. Conventional antidepressant treatment rescues changes in maternal care behaviors in early postpartum, but is less effective in late postpartum [27]. Here, we found that differences in maternal care after CGS were present for only the first few days following birth, with no differences between groups by P6. Maternal care behaviors were not monitored after P6, as behavior experiments performed on P7 could affect behavior in the non-stressed control group. Thus, the potential for later beneficial effects of P7C3-A20 beyond P6 remains to be determined.

Interestingly, we also observed that CGS caused an increase in postpartum locomotor activity in dams in the OFT (Fig. 3I). This finding is in contrast to another report [28] of no effect of CGS on postpartum dam locomotor activity. This behavioral difference may be due to mouse strain differences [29, 30]. We also note that we did not see corresponding increased locomotor activity in the EPM. The reasons for different effects of CGS on locomotor activity in the OFT vs the EPM are not known. Furthermore, as chronic stress is a common and well-established method of modelling depressive-like behavior in mice [31], our lack of a clear and robust depressive-like phenotype in pregnant or postpartum females after CGS was also surprising. At our gestational timepoint, GD17, it seems that CGS causes an anti-depressant phenotype in our chronic stress model, as CGS causes more struggling and longer latency to immobility in the TST (Fig. 3E, G). However, because CGS caused strongly increased baseline activity at GD17 (Fig. 3A, C), we normalized the TST results to distance measurements on the OFT. With baseline activity for each dam taken into consideration, a depressive-like phenotype in response to CGS was observed (Fig 3F, H). We also performed the same normalization on P7 dam TST and FST data and found a depressive-like phenotype on the TST, as evidenced by decreased struggling relative to baseline activity in CGS compared to control dams (Fig 3N). As literature on changes to dam behavior due to CGS is quite sparse, it is difficult to ascertain how stress during pregnancy may cause divergent behavioral phenotypes when compared to male and nulliparous female mice. Additional future studies are therefore needed to more completely characterize the response of dams to stress during pregnancy.

Unexpectedly, we found that CGS protected dams from postpartum behavioral testing induced-weight loss or stagnation of weight gain during gestation. This protective effect of CGS has not previously been reported. Behavioral testing can be considered an acute stressor, especially the TST. While the non-stressed dams showed a somatic response to this acute stress, either a decrease in weight on P8 or a stalling of weight gain on GD18, dams that were chronically stressed lost less weight from P7 to P8 and gained more weight from GD17 to GD18. Previous rodent work shows that early life stress may sensitize animals to later stressors in adulthood [32]. However, it is also possible that an ongoing biological response to chronic stress could prevent an acute stressor from disrupting homeostasis, as long as the acute stressor is applied in close proximity to the chronic stressor. Indeed, it was recently shown that “stress inoculation”, exposing an animal to a chronic mild stress, can protect against acute stress-induced behavioral changes [33]. We thus speculate that an ongoing biological response to CGS may prevent an acute stressor from disrupting homeostasis.

It is important to note other limitations of this study. Maternal care behavior observation was somewhat limited due to difficulty in viewing the nest on early postnatal days when the pups were buried deep in the bedding. Consequently, nuanced maternal behaviors such as arched-back versus blanket nursing were not scored. Future studies may consider a top-view monitoring approach and/or different bedding material to allow for more comprehensive observation.

In conclusion, we observed that maternal care behaviors were disrupted by CGS, and that oral P7C3-A20 treatment of the pregnant mother prevented this deleterious outcome. Interestingly, CGS was also protective against acute stress-induced weight loss, and P7C3-A20 also had a partially protective effect on gestational and postpartum dam weight. Finally, while some changes to dam locomotor and affective-like behaviors were observed, CGS did not elicit a traditional depressive-like phenotype. The basis for the different effects of CGS on pregnant moms and chronic stress on male or nulliparous female mice will be an important area of future investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

AAP was supported by a grant from the Brockman Foundation. AAP was also supported by the Elizabeth Ring Mather & William Gwinn Mather Fund, S. Livingston Samuel Mather Trust, G.R. Lincoln Family Foundation, Wick Foundation, Gordon & Evie Safran, the Leonard Krieger Fund of the Cleveland Foundation, the Maxine and Lester Stoller Parkinson’s Research Fund, the Louis Stokes VA Medical Center resources and facilities, and Project 19PABH134580006-AHA/Allen Initiative in Brain Health and Cognitive Impairment. HES and RS were supported by a Junior Research Program of Excellence awarded to HES from the Roy J. Carver Charitable Trust and research grants from the Nellie Ball Trust to HES. HES was also supported by NIH grant R01 MH122485-01 and by a Career Development Award from the University of Iowa Environmental Health Science Research Center (P30 ES005605). RS was supported by the University of Iowa Graduate Post-Comprehensive Research Fellowship and the Ballard-Seashore Dissertation Fellowship.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author disclosure statement

R.S., L.N., and H.E.S. have no conflicts to disclose. A.A.P. is an inventor on patents related to P7C3.

References

- [1].Champagne FA, Meaney MJ, Stress During Gestation Alters Postpartum Maternal Care and the Development of the Offspring in a Rodent Model, Biological Psychiatry 59(12) (2006) 1227–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Boero G, Biggio F, Pisu MG, Locci V, Porcu P, Serra M, Combined effect of gestational stress and postpartum stress on maternal care in rats, Physiol Behav 184 (2018) 172–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].John RM, Prenatal Adversity Modulates the Quality of Maternal Care Via the Exposed Offspring, Bioessays 41(6) (2019) e1900025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Curley JP, Champagne FA, Influence of maternal care on the developing brain: Mechanisms, temporal dynamics and sensitive periods, Front Neuroendocrinol 40 (2016) 52–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Morin EL, Howell BR, Meyer JS, Sanchez MM, Effects of early maternal care on adolescent attention bias to threat in nonhuman primates, Dev Cogn Neurosci 38 (2019) 100643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Caldji C, Tannenbaum B, Sharma S, Francis D, Plotsky PM, Meaney MJ, Maternal care during infancy regulates the development of neural systems mediating the expression of fearfulness in the rat, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 95(9) (1998) 5335–5340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Gianatiempo O, Sonzogni SV, Fesser EA, Belluscio LM, Smucler E, Sued MR, Cánepa ET, Intergenerational transmission of maternal care deficiency and offspring development delay induced by perinatal protein malnutrition, Nutr Neurosci 23(5) (2020) 387–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Nephew BC, Carini LM, Sallah S, Cotino C, Alyamani RAS, Pittet F, Bradburn S, Murgatroyd C, Intergenerational accumulation of impairments in maternal behavior following postnatal social stress, Psychoneuroendocrinology 82 (2017) 98–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Salisbury AL, O’Grady KE, Battle CL, Wisner KL, Anderson GM, Stroud LR, Miller-Loncar CL, Young ME, Lester BM, The Roles of Maternal Depression, Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Treatment, and Concomitant Benzodiazepine Use on Infant Neurobehavioral Functioning Over the First Postnatal Month, American Journal of Psychiatry 173(2) (2016) 147–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Rai D, Lee BK, Dalman C, Newschaffer C, Lewis G, Magnusson C, Antidepressants during pregnancy and autism in offspring: population based cohort study, BMJ (2017) j2811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cohen LS, Nonacs RM, Bailey JW, Viguera AC, Reminick AM, Altshuler LL, Stowe ZN, Faraone SV, Relapse of depression during pregnancy following antidepressant discontinuation: a preliminary prospective study, Arch Womens Ment Health 7(4) (2004) 217–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Cohen LS, Altshuler LL, Harlow BL, Nonacs R, Newport DJ, Viguera AC, Suri R, Burt VK, Hendrick V, Reminick AM, Loughead A, Vitonis AF, Stowe ZN, Relapse of Major Depression During Pregnancy in Women Who Maintain or Discontinue Antidepressant Treatment, JAMA 295(5) (2006) 499–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Voorhees JR, Remy MT, Cintrón-Pérez CJ, El Rassi E, Khan MZ, Dutca LM, Yin TC, McDaniel LN, Williams NS, Brat DJ, Pieper AA, (−)-P7C3-S243 Protects a Rat Model of Alzheimer’s Disease From Neuropsychiatric Deficits and Neurodegeneration Without Altering Amyloid Deposition or Reactive Glia, Biol Psychiatry 84(7) (2018) 488–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Walker AK, Rivera PD, Wang Q, Chuang JC, Tran S, Osborne-Lawrence S, Estill SJ, Starwalt R, Huntington P, Morlock L, Naidoo J, Williams NS, Ready JM, Eisch AJ, Pieper AA, Zigman JM, The P7C3 class of neuroprotective compounds exerts antidepressant efficacy in mice by increasing hippocampal neurogenesis, Molecular Psychiatry 20 (2014) 500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Pieper AA, Xie S, Capota E, Estill SJ, Zhong J, Long JM, Becker GL, Huntington P, Goldman SE, Shen C-H, Capota M, Britt JK, Kotti T, Ure K, Brat DJ, Williams NS, MacMillan KS, Naidoo J, Melito L, Hsieh J, De Brabander J, Ready JM, McKnight SL, Discovery of a proneurogenic, neuroprotective chemical, Cell 142(1) (2010) 39–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Pieper AA, McKnight SL, Ready JM, P7C3 and an unbiased approach to drug discovery for neurodegenerative diseases, Chem Soc Rev 43(19) (2014) 6716–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wang G, Han T, Nijhawan D, Theodoropoulos P, Naidoo J, Yadavalli S, Mirzaei H, Pieper AA, Ready JM, McKnight SL, P7C3 Neuroprotective Chemicals Function by Activating the Rate-limiting Enzyme in NAD Salvage, Cell 158(6) (2014) 1324–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Pieper A, McKnight S, Evidence of benefit of enhancing nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide levels in damaged of diseased nerve cells., Cold Spring Harbor Symposium Quant Biol 83 (2019) 207–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bavley CC, Kabir ZD, Walsh AP, Kosovsky M, Hackett J, Sun H, Vázquez-Rosa E, Cintrón-Pérez CJ, Miller E, Koh Y, Pieper AA, Rajadhyaksha AM, Dopamine D1R-neuron cacna1c deficiency: a new model of extinction therapy-resistant post-traumatic stress, Mol Psychiatry (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Schroeder R, Sridharan P, Nguyen L, Loren A, Williams NS, Kettimuthu KP, Cintrón-Pérez CJ, Vázquez-Rosa E, Pieper AA, Stevens HE, Maternal P7C3-A20 Treatment Protects Offspring from Neuropsychiatric Sequelae of Prenatal Stress, Antioxid Redox Signal (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bittle J, Stevens HE, The role of glucocorticoid, interleukin-1β, and antioxidants in prenatal stress effects on embryonic microglia, Journal of Neuroinflammation 15(1) (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Gumusoglu SB, Fine RS, Murray SJ, Bittle JL, Stevens HE, The role of IL-6 in neurodevelopment after prenatal stress, Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 65 (2017) 274–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lussier SJ, Stevens HE, Delays in GABAergic interneuron development and behavioral inhibition after prenatal stress: Prenatal Stress and GABAergic Development, Developmental Neurobiology 76(10) (2016) 1078–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Champagne FA, Weaver ICG, Diorio J, Sharma S, Meaney MJ, Natural Variations in Maternal Care Are Associated with Estrogen Receptor α Expression and Estrogen Sensitivity in the Medial Preoptic Area, Endocrinology 144(11) (2003) 4720–4724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Liu D, Diorio J, Tannenbaum B, Caldji C, Francis D, Freedman A, Sharma S, Pearson D, Plotsky PM, Meaney MJ, Maternal Care, Hippocampal Glucocorticoid Receptors, and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Responses to Stress, Science 277(5332) (1997) 1659–1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kott JM, Mooney-Leber SM, Li J, Brummelte S, Elevated stress hormone levels and antidepressant treatment starting before pregnancy affect maternal care and litter characteristics in an animal model of depression, Behav Brain Res 348 (2018) 101–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Qiu W, Duarte-Guterman P, Eid RS, Go KA, Lamers Y, Galea LAM, Postpartum fluoxetine increased maternal inflammatory signalling and decreased tryptophan metabolism: Clues for efficacy, Neuropharmacology 175 (2020) 108174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Salari A-A, Fatehi-Gharehlar L, Motayagheni N, Homberg JR, Fluoxetine normalizes the effects of prenatal maternal stress on depression- and anxiety-like behaviors in mouse dams and male offspring, Behavioural Brain Research 311 (2016) 354–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Mozhui K, Karlsson RM, Kash TL, Ihne J, Norcross M, Patel S, Farrell MR, Hill EE, Graybeal C, Martin KP, Camp M, Fitzgerald PJ, Ciobanu DC, Sprengel R, Mishina M, Wellman CL, Winder DG, Williams RW, Holmes A, Strain differences in stress responsivity are associated with divergent amygdala gene expression and glutamate-mediated neuronal excitability, J Neurosci 30(15) (2010) 5357–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Marchette RCN, Bicca MA, Santos ECDS, de Lima TCM, Distinctive stress sensitivity and anxiety-like behavior in female mice: Strain differences matter, Neurobiol Stress 9 (2018) 55–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Willner P, Muscat R, Papp M, Chronic mild stress-induced anhedonia: A realistic animal model of depression, Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 16(4) (1992) 525–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Aisa B, Tordera R, Lasheras B, Del Río J, Ramírez MJ, Effects of maternal separation on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses, cognition and vulnerability to stress in adult female rats, Neuroscience 154(4) (2008) 1218–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ayash S, Schmitt U, Lyons DM, Müller MB, Stress inoculation in mice induces global resilience, Transl Psychiatry 10(1) (2020) 200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.