Abstract

The Rhode Island Department of Health (RIDOH) uses emergency department data to monitor nonfatal opioid overdoses in Rhode Island. In April 2019, RIDOH detected an increase in nonfatal opioid overdoses in Woonsocket, Rhode Island, and sent an alert to state and local partners (eg, fire departments, emergency departments, faith leaders) with guidance on how to respond. To guide community-level, strategic response efforts, RIDOH analyzed surveillance data to identify overdose patterns, populations, and geographic areas most affected. During April–June 2019, nonfatal opioid overdoses in Woonsocket increased 463% (from 13 to 73) when compared with the previous 3 months. Because of the sustained increase in nonfatal opioid overdoses, RIDOH brought together community partners at a meeting in June 2019 to discuss RIDOH opioid overdose data and coordinate next steps. Data analyses were essential to framing the discussion and allowed community partners at the event to identify an unexpected increase in cocaine-involved nonfatal opioid overdoses in Woonsocket. Many patients with cocaine-involved nonfatal overdoses also had fentanyl in their system, and input from community partners suggested that many patients were unaware of using fentanyl. Community response actions included targeting harm reduction services (eg, distribution of naloxone, mobile needle exchange); deploying peer recovery support specialists to overdose hotspots to connect people to treatment and recovery resources; placing harm reduction messaging in high-traffic areas; and targeted social media messaging. After the meeting, nonfatal opioid overdoses returned to pre-outbreak levels. This case study provides an example of how timely opioid overdose data can be effectively used to detect a spike in nonfatal opioid overdoses and inform a strategic, community-level response.

Keywords: community, nonfatal overdose, opioid, stimulant, surveillance

Mirroring the national epidemic in the United States, the number of unintentional drug overdose deaths in Rhode Island increased steadily from 2009 to 2016, 1 and in 2016, Rhode Island had the 8th highest rate of drug overdose deaths nationally, a rate 50% higher than the national average (30.8 vs 19.8 per 100 000 population). 2,3 To help combat this epidemic, the Rhode Island Department of Health (RIDOH), in collaboration with other local and state partners, launched several initiatives to prevent drug-related harms in Rhode Island. 4 -10 One initiative was to use overdose surveillance data to detect outbreaks in nonfatal opioid overdoses and inform targeted community-level responses.

This case study describes how RIDOH established a near–real-time overdose surveillance system; used the data to detect a spike in nonfatal opioid overdoses in Woonsocket, Rhode Island; and disseminated the information to rapidly inform a strategic, community-level response.

Methods

Establishing an Overdose Surveillance System

To help generate real-time overdose surveillance data, beginning in April 2014, emergency departments (EDs) in Rhode Island were required to report all suspected opioid overdoses to RIDOH within 48 hours of admission. 11 In October 2015, web-based data collection for the 48-Hour Overdose Reporting System began and included nonidentifiable patient demographic characteristics, naloxone administration and distribution, and follow-up services offered. To supplement the 48-Hour Overdose Reporting System, in 2016 RIDOH began using the Rhode Island Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Information System (RI-EMSIS), which reports real-time data on prehospital assessments and care for opioid overdoses. 12 RI-EMSIS surveillance data provide address information for all overdose-related deployments made by EMS staff members and can be mapped to show more granular locations of overdose hotspots. Finally, beginning in January 2019, RIDOH implemented an ED nonfatal toxicology surveillance system in which biological samples from people who have had a nonfatal opioid overdose are sent to the state medical laboratory to help monitor the illicit opioid drug supply, patterns of drug use, and factors associated with drug use outcomes. Although this system collects data on the opioids that contribute to overdoses, this system also captures data on other non-opioid drug classes, which can be helpful for examining polysubstance use and potential opioid contamination of non-opioid drug classes.

Detecting Spikes in Nonfatal Opioid Overdoses

To monitor spikes in ED visits for suspected opioid overdoses in Rhode Island, RIDOH divided the state into 11 Regional Overdose Action Area Response (ROAAR) regions. Using 48-Hour Overdose Reporting System data from the previous year, RIDOH calculated the average number of weekly ED visits for each region based on the location of each overdose and set a ROAAR alert threshold at 2 SDs above the weekly average. In 2019, Woonsocket, a city in northern Rhode Island, had a ROAAR alert threshold of 4 ED visits for suspected opioid overdoses within a 7-day period.

If a spike is identified, heat maps are generated using RI-EMSIS data. Suspected opioid overdose–related EMS runs are identified using a validated case definition, 13 and the ArcMAP version 10.7 (ArcGIS) kernel density feature is used to produce the maps.

Disseminating the Information to Rapidly Inform a Response

To ensure the data were actionable, beginning in April 2017, RIDOH established weekly surveillance, response, and intervention calls with state partners from public health, behavioral health, and law enforcement to review data from the 48-Hour Overdose Reporting System and discuss factors that may be contributing to any observed trends. This multidisciplinary team includes surveillance, programmatic, medical, and communications staff members at RIDOH and partners at the Rhode Island Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities, and Hospitals (BHDDH); the Rhode Island State Police; and the Rhode Island State Fusion Center.

After the weekly call, if the number of nonfatal opioid overdose–related ED visits in any region exceeds the predetermined threshold, a ROAAR alert is sent to state and local partners with guidance on how to respond. After a ROAAR alert is issued, a RIDOH community outreach liaison reaches out to local points of contact to provide state-level support and technical assistance. In addition, RIDOH and BHDDH deploy peer recovery support specialists to regions with increased overdose activity to distribute safer drug use resources such as naloxone. These peers also connect people who use drugs with local treatment and recovery support services.

To guide community-level strategic response efforts after a ROAAR alert is issued, RIDOH analyzes data from multiple surveillance systems to identify where the overdoses are occurring, what populations are affected, and what substances may be contributing to the overdoses and provides this information to the community.

When communities receive 3 ROAAR alerts within a 6-week period, community leaders are invited to attend a Community Overdose Engagement meeting. Community Overdose Engagement meetings offer the opportunity for community leaders to connect with each other and RIDOH staff members to share concerns, develop action plans to reduce the number of drug overdoses, and coordinate messaging and response activities. As one community partner noted, “The Community Overdose Engagement initiative, among others, has created pathways for genuine engagement with many different stakeholders, thus improving the possibility for conceiving and implementing strategies that can be implemented and have a real impact on the epidemic.”

Funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is used to partially support the RI-EMSIS and the ED nonfatal toxicology surveillance platforms. Of note, CDC does not support activities related to conducting research or purchasing fentanyl test strips, and CDC funds were not used to purchase fentanyl test strips as part of this response. This response was part of RIDOH’s response to the opioid overdose epidemic in Rhode Island and did not require institutional review board approval.

Outcomes

Hospitals in Rhode Island reported 9 ED visits for suspected opioid overdoses to RIDOH that occurred in Woonsocket during April 8-14, 2019 (surveillance week 14), which was more than double RIDOH’s predetermined ROAAR threshold for Woonsocket of 4 ED visits in 1 week. This unusual overdose activity was detected and discussed on the weekly surveillance, response, and intervention call of state partners with public health, behavioral health, and law enforcement officials on April 16. In response to the high number of suspected overdoses and feedback from partners, on April 16, RIDOH issued its first public health advisory to the Woonsocket community describing the rise in ED visits for suspected opioid overdoses and issuing tailored public health messages to various community partners, including EMS, fire departments, and law enforcement; EDs and hospital providers; substance use disorder and medication-assisted treatment providers and recovery community representatives; pharmacists; faith leaders; city/town leadership; and the general public.

After the initial dissemination of the ROAAR alert during surveillance week 14 and 2 subsequent ROAAR alerts during weeks 15 and 16, RIDOH invited community partners to attend a Community Overdose Engagement event held at a RIDOH meeting space on June 20, 2019. More than 60 people from RIDOH, BHDDH, the Governor’s Office, Rhode Island State Police, the Rhode Island State Fusion Center, local pharmacies, hospitals, and community organizations attended the session.

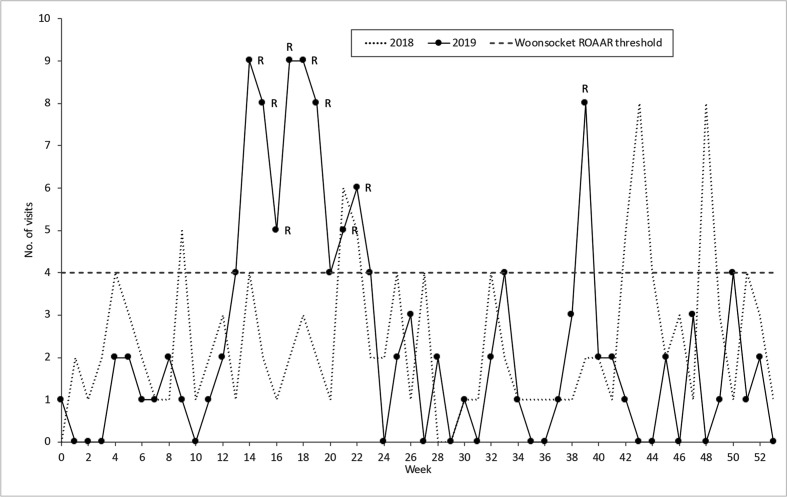

At this session, RIDOH presented information from several sources to serve as resources for the community. First, RIDOH shared data from the 48-Hour Overdose Reporting System to show recent weekly trends in the number of ED visits for suspected opioid overdoses in Woonsocket (Figure 1). When comparing nonfatal opioid overdoses in Woonsocket from January–March 2019 with nonfatal opioid overdoses from April–June 2019, the number of nonfatal opioid overdoses increased 462%, from 13 to 73. To demonstrate consistency across surveillance platforms as a sensitivity analysis, RIDOH also shared a comparison of monthly trends in ED and EMS data for suspected opioid overdoses in Woonsocket from January 2017 through May 2019; both ED and EMS data detected a similar increase in suspected opioid overdoses beginning in April 2019.

Figure 1.

Number of suspected opioid overdose–related emergency department (ED) visits with an incident location in the region, by week, Woonsocket, Rhode Island, January 1, 2018, through December 31, 2019. “R” indicates ROAAR alert. Abbreviation: ROAAR, Regional Overdose Action Area Response. Rhode Island’s population is stable, and changes in the number of nonfatal opioid overdoses over time are not attributed to any changes in the underlying population.

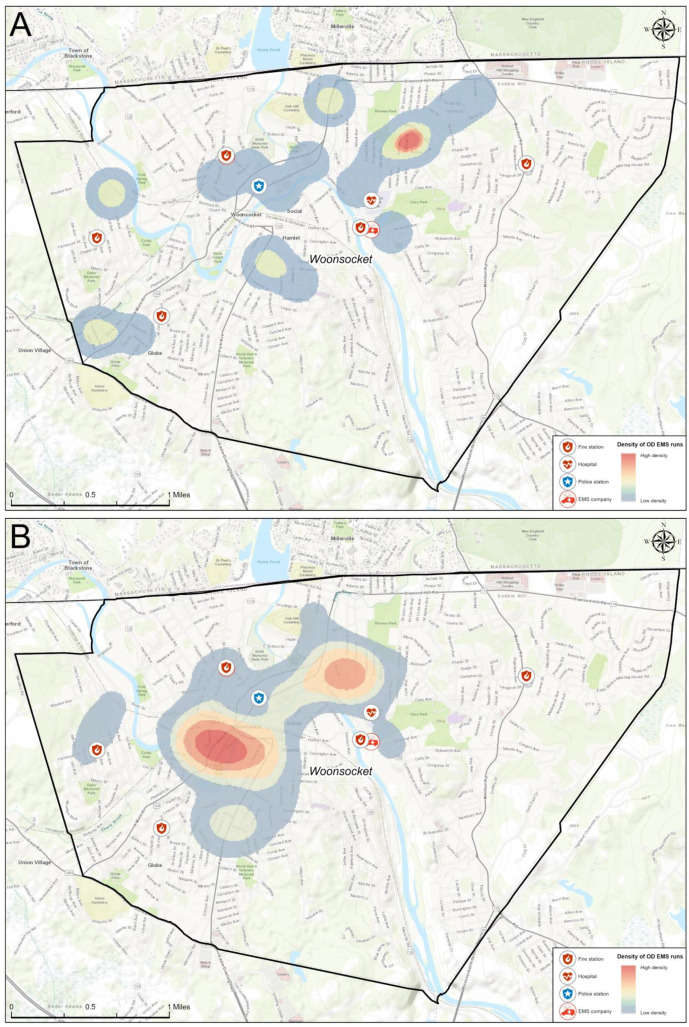

Second, RIDOH shared heat maps of overdose incident locations in Woonsocket using data from RI-EMSIS displaying overdose locations from 2 periods: (1) January 1–March 31, 2019, before the spike in overdoses, and (2) April 1–June 16, 2019 (Figure 2). Opioid overdoses occurring from April 1 through June 16 were concentrated in distinct geographic locations compared with the areas previously experiencing elevated numbers of opioid overdose–related EMS deployments.

Figure 2.

Heat maps of opioid overdose (OD)–related emergency medical services (EMS) runs in Woonsocket, Rhode Island, in (A) January 1–March 31, 2019, and (B) April 1–June 16, 2019.

Third, RIDOH analyzed data from the 48-Hour Overdose Reporting System to show the demographic characteristics of people experiencing opioid overdoses in Woonsocket. Comparing the 2 periods (January–March 2019 and April–June 2019), the percentage of opioid overdoses decreased slightly among males (from 77% [10/13] to 68% [50/73]) and increased among people aged <35 (from 46% [6/13] to 64% [47/73]).

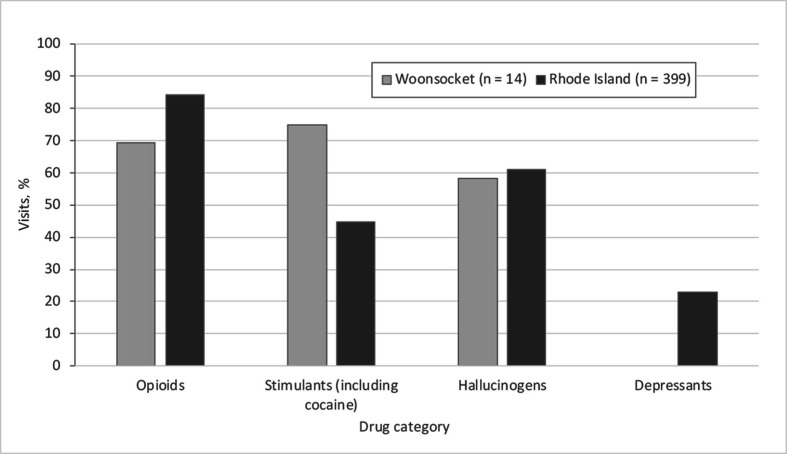

Finally, RIDOH used data from the ED nonfatal toxicology system to compare opioid overdose ED patients in Woonsocket with opioid overdose ED patients in the rest of Rhode Island during January–April 2019 to examine polysubstance use and potential opioid contamination of non-opioid drug classes. Among people admitted for an opioid overdose, the percentage testing positive for stimulants (including cocaine) was higher in Woonsocket (75%; 9 of 12) than in Rhode Island (45%; 156 of 349) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Percentage of nonfatal opioid overdose–related emergency department (ED) visits that were positive for each drug category, Woonsocket, Rhode Island, and Rhode Island, January 1–April 30, 2019. No nonfatal opioid overdose–related ED visits were recorded for depressants in Woonsocket.

During the Woonsocket Community Overdose Engagement meeting, RIDOH presented these data, and community members could voice their experiences and concerns. Data findings and input from community partners suggested an increase in cocaine-related, nonfatal opioid overdoses in the community. Local health care providers shared that opioid overdoses appeared to be occurring among recreational cocaine users, many of whom were unaware that they had fentanyl in their system.

During the meeting, participants coordinated a municipal-level response by planning the deployment of harm reduction services such as naloxone, fentanyl test strip kits, and sterile needle distribution to overdose hotspots identified from the RI-EMSIS data. BDDH deployed peer recovery specialists, and RIDOH created tailored communication materials that were placed in hotspot areas to educate and connect people with counseling, treatment, and harm reduction services. The messaging targeted people who might use cocaine and other non-opioid drugs casually. Delivering data-informed messaging to identified hotspots allowed the community to maximize the use of community resources with limited funds.

In addition, through communication with the Rhode Island State Fusion Center, RIDOH learned about an influx of counterfeit opioid pills that contained fentanyl in Rhode Island. This information allowed RIDOH communication staff members to create tailored communication materials and run a paid social media campaign on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. Social media messaging targeted Woonsocket residents using location-based marketing (ie, geofencing). Local health care treatment providers and people from the recovery community also distributed educational resources to people in Woonsocket to increase awareness of the situation from June 1 through August 31, 2019.

In total, 8 ROAAR alerts were issued between weeks 14 and 23 (April 8-14 and June 10-16). After the Woonsocket Community Overdose Engagement meeting on June 20, 2019, only 1 additional ROAAR alert was issued for Woonsocket for the remainder of 2019 (during week 39) (Figure 1). After increasing 462% during April–June 2019, the number of nonfatal opioid overdoses declined 77% during July–September 2019 and returned to baseline levels (ie, 17) during the following 3-month period.

Lessons Learned

This case study provides an example of how timely overdose data can be used to detect a spike in nonfatal overdoses and inform a strategic, community-level response. To our knowledge, this is the first time that surveillance data have been used to detect and respond to an increase in nonfatal overdoses in real time. Specifically, this case study highlights the importance of (1) pre-established relationships with other organizations (eg, public health, medical providers, law enforcement, local community partners and champions) so that they can be leveraged for rapid coordination once an increase is identified, (2) the importance of framing discussions with partners using rapid surveillance data from multiple systems, and (3) how to develop data collection processes that allow for the production of heatmaps, which are particularly helpful for targeting interventions rapidly. It is our hope that this information can be used by other public health jurisdictions to create similar systems. Although this case study in Rhode Island is just one example of an opioid overdose outbreak that RIDOH responds to, this response represents only 4 of 15 ROAAR alerts and 1 of 2 Community Overdose Engagement meetings that RIDOH hosted in 2019. These alerts and meetings are 2 initiatives that RIDOH has implemented to prevent drug-related harms in Rhode Island. Additional initiatives include the following:

Creating the Rhode Island Prescription Drug Monitoring Program to prevent drug diversion and improve patient care

Using academic detailing to educate health care providers about safer prescribing practices

Increasing the knowledge, availability, and accessibility of naloxone and fentanyl test strips in the community

Decreasing fear, bias, and discrimination of substance use disorders and increasing awareness of harm reduction strategies through public awareness campaigns

Providing mini-grants to community-based agencies to pilot innovative interventions to address the opioid overdose epidemic

Launching the Rhode Island Heroin Opioid Prevention Effort Initiative to encourage law enforcement to work with clinicians to identify people at high risk of overdose, link them with recovery resources, and promote pre-arrest diversion

Launching the governor’s Overdose Prevention and Intervention Task Force to bring together public health, public safety, behavioral health, and health care professionals to provide high-level leadership and coordination of overdose prevention, treatment, and recovery strategies across the state.

Potentially as a result of this multipronged approach, after increasing from 2009 to 2016, the number of opioid overdose deaths decreased by 8.3% from 2016 to 2019 in Rhode Island. 1

The higher proportion of cocaine-associated overdoses observed in Woonsocket reflects a national increase in cocaine-related overdoses involving opioids and, in 2017, 72.7% of all cocaine overdose deaths in the United States involved opioids. 14,15 In the absence of regular and recent opioid use, an individual unintentionally using cocaine and fentanyl or a fentanyl derivative would be highly susceptible to an overdose because of the rapid onset and potency of fentanyl. For this reason, having naloxone on hand when using any illicit substance is highly recommended.

In informal discussions with partners about the response, we cannot overemphasize the usefulness of bringing together all partners for the Community Overdose Engagement meeting and the value of having the discussion framed by data from the outbreak. After being presented with data on the increase in cocaine-related nonfatal opioid overdoses in Woonsocket, community partners and health care providers from local EDs said that many overdoses appeared to be occurring among recreational cocaine users, many of whom were unaware that they had fentanyl in their system. Had the conversation not been framed by data, these partners may not have shared these experiences and the response would not have been able to target recreational cocaine users so rapidly.

In addition, community partners commented on the value of the hotspot maps with community landmarks. Because many community partners have limited local funds and personnel, the maps provided tangible locations toward which community partners could target their efforts and resources. Because the overdose hotspots for this outbreak did not overlap with previous hotpots, the timely nature of these maps and data also allowed partners to effectively identify where the hotspots currently were. As one community outreach organization noted, “The objective of our work is to rapidly respond to any region that is experiencing an increased number of overdoses, providing critical support and coordination of treatment referrals while utilizing evidence-based practices. ROAAR alerts, PORI [Prevent Overdose RI] data and overdose maps allow us to prioritize which regions of Rhode Island we should be targeting our efforts toward each day and week.”

A major strength of this response is RIDOH’s ability to receive near–real-time overdose-related data from multiple surveillance systems, which were used to both detect the outbreak and inform the response. In addition, the pre-established relationships among public health, medical providers, law enforcement, and local community partners and champions were essential to coordinate the response in a timely manner and empower the community.

This response was subject to at least 2 limitations. First, because of the absence of a control group, we were unable to determine if the decline observed in nonfatal overdoses was purely temporal or was the result of the interventions enacted during this response. Second, to report cases to the 48-Hour Overdose Reporting System, hospital administrators must manually enter and upload all case information in a timely fashion. As such, a low number of ED visits for suspected opioid overdoses during each week could result from a true decline or from a lag in reporting. As an alternative to this system, in 2019 RIDOH began implementing CDC’s National Syndromic Surveillance Program Electronic Surveillance System for the Early Notification of Community-based Epidemics, which is an entirely automated system that captures real-time information directly from electronic health records. Unaffected by reporting delays, the CDC surveillance program, once fully validated, will provide a sustainable surveillance platform that will not rely on hospital administrators to manually enter the data, will ensure RIDOH receives data in real time, and will accurately detect changes in suspected opioid overdoses in Rhode Island communities.

This case study demonstrates the feasibility of using timely overdose data to detect a spike in nonfatal opioid overdoses and inform a strategic response. RIDOH will continue to adapt and innovate to find more efficient methods for monitoring drug-related harms and more effectively use data to work alongside communities to address the opioid overdose epidemic in Rhode Island.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Meghan McCormick, Linda Mahoney, and Ewa King for their contribution to the response, without which this article would not have been possible.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This response was funded by the Rhode Island Department of Health and by the Overdose to Action grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

ORCID iD

Benjamin D. Hallowell, PhD https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6943-9615

References

- 1. Prevent Overdose RI . Overdose death data. 2020. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://preventoverdoseri.org/overdose-deaths/

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2016 drug overdose death rates. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths/drug-overdose-death-2016.html

- 3. Hedegaard H., Warner M., Miniño AM. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;294:1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McDonald JV. Using the Rhode Island prescription drug monitoring program (PMP). R I Med J. 2014;97(6):64-65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bowman S., Engelman A., Koziol J., Mahoney L., Maxwell C., McKenzie M. The Rhode Island community responds to opioid overdose deaths. R I Med J. 2014;97(10):34-37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McCormick M., Koziol J., Sanchez K. Development and use of a new opioid overdose surveillance system, 2016. R I Med J. 2013;100(4):37-39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jiang Y., McDonald JV., Koziol J., McCormick M., Viner-Brown S., Alexander-Scott N. Can emergency department, hospital discharge, and death data be used to monitor burden of drug overdose in Rhode Island? J Public Health Manag Pract. 2017;23(5):499-506. 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Marshall BDL., Yedinak JL., Goyer J., Green TC., Koziol JA., Alexander-Scott N. Development of a statewide, publicly accessible drug overdose surveillance and information system. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(11):1760-1763. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Waye KM., Yedinak JL., Koziol J., Marshall BDL. Action-focused, plain language communication for overdose prevention: a qualitative analysis of Rhode Island’s overdose surveillance and information dashboard. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;62:86-93. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Samuels EA., McDonald JV., McCormick M., Koziol J., Friedman C., Alexander-Scott N. Emergency department and hospital care for opioid use disorder: implementation of statewide standards in Rhode Island, 2017-2018. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(2):263-266. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.216-RICR-20-20-5 (2014).

- 12. Lasher L., Jason Rhodes J., Viner-Brown S. Identification and description of non-fatal opioid overdoses using Rhode Island EMS data, 2016-2018. R I Med J. 2019;102(2):41-45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rhode Island Department of Health . Rhode Island Enhanced State Opioid Overdose Surveillance (ESOOS): case definition for emergency medical services (EMS). 2019. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://health.ri.gov/publications/guidelines/ESOOSCaseDefinitionForEMS.pdf

- 14. Kariisa M., Scholl L., Wilson N., Seth P., Hoots B. Drug overdose deaths involving cocaine and psychostimulants with abuse potential—United States, 2003-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(17):388-395. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6817a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hoots B., Vivolo-Kantor A., Seth P. The rise in non-fatal and fatal overdoses involving stimulants with and without opioids in the United States. Addiction. 2020;115(5):946-958. 10.1111/add.14878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]