Abstract

The budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae contains two homologues of bacterial IscA proteins, designated Isa1p and Isa2p. Bacterial IscA is a product of the isc (iron-sulfur cluster) operon and has been suggested to participate in Fe-S cluster formation or repair. To test the function of yeast Isa1p and Isa2p, single or combinatorial disruptions were introduced in ISA1 and ISA2. The resultant isaΔ mutants were viable but exhibited a dependency on lysine and glutamate for growth and a respiratory deficiency due to an accumulation of mutations in mitochondrial DNA. As with other yeast genes proposed to function in Fe-S cluster assembly, mitochondrial iron concentration was significantly elevated in the isa mutants, and the activities of the Fe-S cluster-containing enzymes aconitase and succinate dehydrogenase were dramatically reduced. An inspection of Isa-like proteins from bacteria to mammals revealed three invariant cysteine residues, which in the case of Isa1p and Isa2p are essential for function and may be involved in iron binding. As predicted, Isa1p is targeted to the mitochondrial matrix. However, Isa2p is present within the intermembrane space of the mitochondria. Our deletion analyses revealed that Isa2p harbors a bipartite N-terminal leader sequence containing a mitochondrial import signal linked to a second sequence that targets Isa2p to the intermembrane space. Both signals are needed for Isa2p function. A model for the nonredundant roles of Isa1p and Isa2p in delivering iron to sites of the Fe-S cluster assembly is discussed.

Iron-sulfur (Fe-S) cluster prosthetic groups play a key role in a wide range of enzymatic reactions, as well as serving as regulatory switches. Key enzymes containing Fe-S clusters include aconitase and succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) in the tricarboxylic acid cycle, the Rieske iron-sulfur protein in the respiratory chain, homoaconitase, which is required for fungal lysine biosynthesis, the nitrogenase iron protein involved in nitrogen fixation, and iron-responsive element binding protein 1, which regulates ferritin and transferrin receptor production in mammals (4, 22, 32, 36, 37).

The formation of Fe-S clusters has been most thoroughly studied in the case of nitrogenase from the nitrogen-fixing bacterium Azotobacter vinelandii (56). The proteins responsible for the synthesis, maturation, and regulation of nitrogenase are encoded by genes present on the nif operon (19). Two proteins implicated in biosynthesis of the nitrogenase Fe-S cluster include NifS and NifU (19). NifS is a cysteine desulfurase that produces the inorganic sulfide for the cluster (57), whereas NifU is speculated to participate in Fe mobilization for the Fe-S cofactor (11, 54, 55). An additional protein encoded by nif, Orf6, may also be involved in assembly of the nitrogenase cluster, although its precise role is unknown.

The recently identified iscSUA-hscBA-fdx operon from A. vinelandii contains genes exhibiting strong homology to nifS, nifU, and orf6 (55). Additionally, this operon encodes the molecular chaperones HscB and HscA, which may facilitate the folding of Fe-S proteins (41, 44, 49). The isc operon has been identified in both nitrogen-fixing and non-nitrogen-fixing bacteria, such as Escherichia coli, suggesting that the isc genes function in the assembly or repair of Fe-S clusters for enzymes other than nitrogenase (55). Homologues of components of the iscSUA-hscBA-fdx operon have been noted in eukaryotic cells. For example, proteins exhibiting strong homology to IscS (sulfide donor), IscU (iron donor), HscB and HscA (molecular chaperones), and Fdx (ferredoxin) have been identified in baker's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), and there is evidence supporting a role for these proteins in the assembly or repair of Fe-S clusters (13, 21, 25, 26, 38, 39, 45). Notably, all eukaryotic proteins implicated in the biosynthesis of Fe-S centers contain consensus sequences for targeting to the mitochondrion, suggesting that the mitochondrion is a principal location for assembly or repair of Fe-S clusters.

In the study presented herein, we investigated proteins from S. cerevisiae that exhibit strong homology to the bacterial IscA product of the isc gene cluster. Two proteins, designated Isa1p and Isa2p, contain a C-terminal region exhibiting at least 50% similarity to bacterial proteins encoded by orf6 in the nif operon and by iscA in the isc operon, respectively. Both Isa1p and Isa2p are required for normal mitochondrial iron metabolism and appear to play an important role in the building or repair of mitochondrial Fe-S centers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions.

The parental strains used in this study include BY4741 (MATa leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 his3-Δ1) and the isogenic MATα strain, BY4742 (5). The isa1::kanMX4 deletion was made by replacing the ISA1 open reading frame with KanMX4, as described previously (50, 52), generating strain 1515. To construct the isa2Δ haploid strain, one allele of the ISA2 gene was deleted in an isa1Δ/ISA1 heterozygous diploid (created by crossing strains 1515 and BY4742) using the isa2Δ::HIS3 disruption plasmid pΔISA2. Meiosis resulted in four viable spores, and the isa2Δ::HIS3 and isa1Δ::kanr isa2Δ::HIS3 spores were isolated as strains LJ102 and LJ103, respectively. The fet3Δ deletion strains were created by disrupting the FET3 gene of BY4741, 1515, LJ102, and LJ103 using the fet3Δ::URA3 plasmid pΔFET3 (kind gift of A. Dancis), resulting in the strains LJ105 (fet3Δ), LJ106 (fet3Δ isa1Δ), LJ107 (fet3Δ isa2Δ), and LJ108 (fet3Δ isa1Δ isa2Δ), respectively. The [rho−] strain LJ104 was obtained by plating BY4742 onto enriched medium supplemented with 0.004% ethidium bromide and by isolating small colonies that failed to grow on medium containing glycerol as a carbon source. All yeast transformations were performed using the lithium acetate procedure (14). Cells were propagated either in enriched yeast extract-peptone-based medium supplemented with 2% glucose (YPD) or raffinose (YPR) or in minimal synthetic dextrose (SD) medium (42).

Plasmids.

To construct the isa2Δ::HIS3 plasmid, ISA2 sequences from positions −816 to −9 and +564 to +1061 were amplified by PCR using primers that introduced EcoRI sites at −816 and +1061, a BamHI site at −9, and a SalI site at +564. The PCR products were digested at these sites and ligated in a trimolecular reaction to the SalI and BamHI sites of the HIS3 integrating vector pRS403 (43). The resulting plasmid, pΔISA2, was linearized with EcoRI and used to delete the chromosomal ISA2 gene.

All expression plasmids for Isa1p and Isa2p utilized epitope-tagged versions of the proteins in which a single copy of the hemagglutinin (HA) epitope from Haemophilus influenzae was placed at the C terminus of the protein. A vector for expressing these proteins under their own promoter was constructed by inserting the CYC1 terminator from p426-MET25 (30) and the HA-encoding sequence from pYeF2 (7) into the BamHI/KpnI and BamHI/EcoRI sites, respectively, of pRS316 (URA3 CEN [43]), generating pHAt-316. The promoters of the ISA1 (−820 to −4) and ISA2 (−789 to −4) genes were amplified by PCR, with SacI and BamHI sites engineered at the upstream and downstream positions, and were inserted at these same sites into pHAt-316, creating pLJ100 (ISA1 promoter) and pLJ200 (ISA2 promoter). The ISA1 and ISA2 coding sequences were amplified by PCR, introducing BamHI and NotI sites at −4 and the stop codon, and were inserted at these same sites in pLJ100 (for Isa1p), pLJ200 (for Isa2p), or vector pYeF2 (7) for galactose-inducible expression of Isa1p and Isa2p. The final plasmids were pLJ101 and pLJ201 (Isa1-HA and Isa2-HA under the control of the native promoter) and pLJ114 and pLJ210 (Isa1-HA and Isa2-HA under the control of the GAL1 promoter).

To create N-terminal deletions of Isa1p, pLJ101 was used as a template for site-directed mutagenesis (Quikchange kit; Stratagene) to introduce BamHI and NdeI sites at codons 32 or 61 and BglII and NdeI sites at codon 144, creating or maintaining methionine residues. The intervening sequences between the 5′ BamHI and internal BamHI or BglII sites were removed by restriction digestion and religation, generating plasmids expressing Δ1–31, Δ1–61, and Δ1–144 variants of Isa1p. Internal deletions of residues 32 to 61, 61 to 144, and 32 to 144 were generated similarly by introducing BglII sites at the indicated positions, followed by restriction digestion and religation. To create the Sod2-Isa1p fusion construct, the mitochondrial targeting sequence of S. cerevisiae Sod2p (amino acids 1 to 27) was amplified by PCR, introducing a 5′ BamHI site and a 3′ NdeI site. The resultant sequence, encoding Sod2 and the mitochondrial leader sequence, was inserted at the BamHI and NdeI sites of Δ1–144 Isa1p, resulting in the plasmid expressing Sod2, the mitochondrial leader sequence, and Isa1. N-terminal truncations of Isa2p (Isa2 Δ1–31 and Δ1–56) were generated in a manner similar to that of Isa1p, using the plasmid pLJ201 as a template for site-directed mutagenesis. An internal deletion mutant (Isa2 Δ31–56) was generated introducing NcoI sites at positions 31 and 56, followed by digestion at these sites and religation.

To monitor the expression of all mutants, each was subcloned into vector pYeF2 for galactose-inducible expression. Cysteine-to-serine substitutions in Isa1p and Isa2p were generated by site-directed mutagenesis, using as templates plasmids pLJ101, pLJ201, and pLJ202.

The sequence integrity of all the Isa1p- and Isa2p-expressing plasmids was ensured by double-stranded DNA sequencing (core facility, Johns Hopkins University).

Biochemical analyses.

For iron accumulation studies and for enzymatic assays of SDH and malate dehydrogenase (MDH), crude mitochondria were isolated from cell lysates prepared by glass homogenization as previously described (13). Iron analysis of either whole cells or isolated mitochondria was carried out on a Perkin-Elmer model 4000 graphite furnace atomic-absorption spectrophotometer according to the manufacturer's specifications. Aconitase, SDH, and MDH assays were conducted essentially as described previously (29, 45). One unit of MDH activity was defined as 1 nmol of NADH reduced/min/mg of protein.

Western blot analyses were conducted with strain BY4741 transformed with the pYeF2-derived constructs in which Isa1-HA or Isa2-HA production was driven by the GAL1 promoter. Cells were grown to stationary phase in synthetic selective medium with 2% raffinose, diluted in YPR medium to an A600 of 0.1, and grown to a final A600 of 4.0. Protein expression was induced by the addition of 2% galactose, and incubations proceeded for no more than 3 h. For preparation of cell lysates, yeast cells were converted to spheroplasts, as previously described (8), and were gently lysed by Dounce homogenization in a SEM buffer containing 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 10 mM MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) (pH 7.2), and 0.5% bovine serum albumin. The soluble fraction representing total cell lysate was then clarified by centrifugation for 5 min at 3,000 rpm in an IEC microcentrifuge. As needed, lysates were further fractionated into mitochondrial (pellet) and postmitochondrial (supernatant) fractions as described previously (3) by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 10 min. The pelleted mitochondria were washed in SEM buffer and separated into inner membrane space (soluble) and matrix (pellet) fractions by resuspension in a hypotonic buffer (SEM lacking sucrose), followed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm. All samples were analyzed by Western blotting, as already described (27), using 40 μg of protein (whole cell lysates) or the identical cell equivalents (mitochondrial fractions). The Isa proteins were detected by using a polyclonal 12CA5 anti-HA antibody (Boehringer Mannheim), and mitochondrial fractions were monitored by using antibodies directed against cytochrome b2 in the intermembrane space and against Mas2 in the matrix (kind gifts of Rob Jensen). Detection employed the ECL kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) according to the manufacturer's specifications.

RESULTS

S. cerevisiae homologues of IscA.

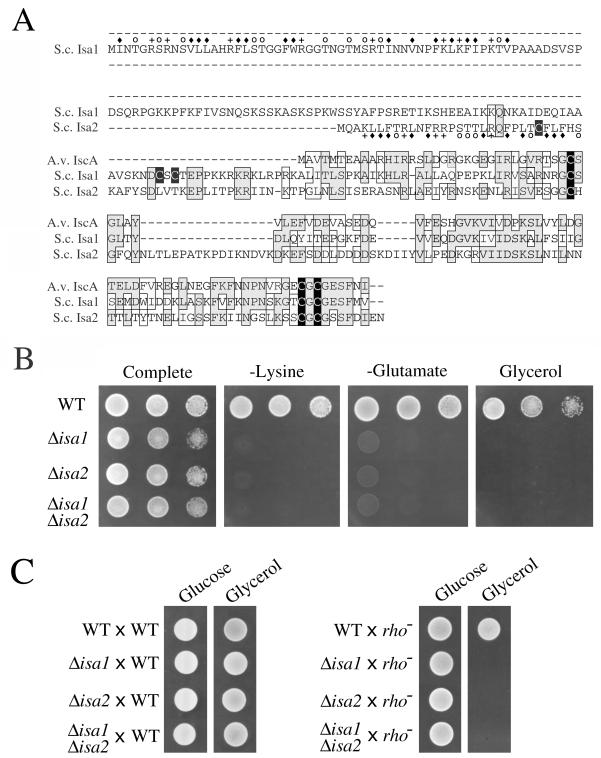

Inspection of the yeast genome database revealed the presence of two S. cerevisiae proteins with significant homology to bacterial IscA, designated Isa1p and Isa2p (Fig. 1A). The C-terminal domain of Isa1p is 39% identical and 56% similar to A. vinelandii IscA and 37% identical and 57% similar to Orf6 of the nif operon. The analogous region of Isa2p contains two short insertion sequences that are not present in the yeast Isa1p or bacterial IscA; otherwise, this domain of Isa2p is 35% identical and 50% similar to A. vinelandii IscA and 37% identical and 50% similar to Orf6. In addition to these C-terminal IscA-like sequences, both Isa1p and Isa2p contain unique N-terminal regions of 144 and 56 residues. Portions of these N-terminal regions in Isa1p and Isa2p conform to the rules for N-terminal mitochondrial targeting sequences (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

The ISA1 and ISA2 genes of S. cerevisiae. (A) Sequence comparison of A. vinelandii (A.v.) IscA with Isa1p and Isa2p from S. cerevisiae (S.c.). Conserved and similar residues are in boxes, and cysteine residues are indicated by black. The potential mitochondrial targeting sequences are marked above the sequence for Isa1p and below the sequence for Isa2p, as follows: ⧫, hydrophobic residues; +, acidic residues; and ○, hydroxylated residues. (B) The designated yeast strains were tested for growth by plating 105, 104, or 103 cells in 10 μl of solution onto minimal SD complete medium or the same medium lacking lysine or glutamate or on enriched medium containing glycerol as a carbon source, as indicated. (C) Diploid cells resulting from the designated crosses were spotted onto enriched medium containing either glucose or glycerol as a carbon source. Cells were grown for 2 days at 30°C. Strains utilized: Δisa1, 1515; Δisa2, LJ102; Δisa1 Δisa2, LJ103; [rho−], LJ104; WT, BY4741 (B and C, right) or BY4742 (C, left).

To study the role of these IscA homologues in yeast, targeted disruptions of ISA1 and ISA2 were generated. The resulting strains were viable in complete medium containing glucose yet exhibited negligible growth on medium lacking either lysine or glutamate (Fig. 1B). In addition, these strains exhibited an apparent respiratory deficiency, as they were unable to utilize glycerol as a carbon source. Strains containing a double disruption of ISA1 and ISA2 were also viable and exhibited growth requirements identical to those seen with a single isa1Δ or isa2Δ mutant (Fig. 1B). In general, the effects of a double isa1Δ isa2Δ mutation were nonadditive.

The wild-type ISA1 and ISA2 genes were reintroduced into their corresponding mutant strains by expression from a centromeric plasmid. Expression of episomal ISA1 or ISA2 effectively rescued the lysine and glutamate growth requirements of the corresponding isa1 or isa2 mutant (data not shown). In contrast, transformation with the wild-type ISA genes failed to complement the growth defect of either isa mutant on nonfermentable carbon sources (data not shown). This inability to complement the respiratory defect of isaΔ strains was consistent with the accumulation of [rho−] mutations in the mitochondrial DNA of the mutants. To address whether the isa1Δ and isa2Δ mutants had acquired mitochondrial DNA mutations, these haploid strains were crossed with either a wild-type yeast or an isogenic [rho−] mutant, and growth of the resultant diploids on glycerol was monitored. As seen in Fig. 1C, diploids generated from crossing with a wild-type strain exhibited positive growth on medium containing glycerol; by comparison, no such complementation was observed with diploids derived from the isa mutant crossed with the [rho−] strain. This result suggests that the respiratory defect of the isaΔ mutants is due to secondary damage to mitochondrial DNA.

Mitochondrial defects associated with isa1Δ and isa2Δ strains.

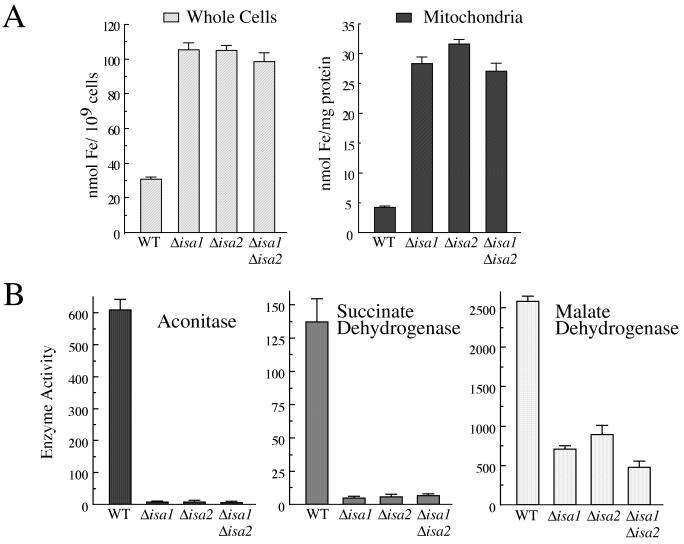

Elevated levels of mitochondrial iron have been associated with mutations in a number of yeast genes proposed to participate in Fe-S cluster assembly, including ATM1 (20, 21), SSQ1 (23), NFS1 (21, 26), YAH1 (25), and ISU1, ISU2, and NFU1 (13, 39). We addressed whether a similar increase in mitochondrial iron was affected in isa1Δ, isa2Δ, or isa1Δ isa2Δ mutants. As seen in Fig. 2A, total cellular iron levels were increased approximately threefold in all three isaΔ mutants compared to the isogenic wild-type strain. The iron content of isolated mitochondria was found to be eightfold higher in the isa1Δ, isa2Δ, and isa1Δ isa2Δ strains (Fig. 2A). Again, there was no added effect from combining mutations in ISA1 and ISA2.

FIG. 2.

Hyperaccumulation of iron and enzymatic defects in isa mutants. (A) The indicated yeast strains were grown to mid-log phase, and the iron content was measured either in whole cells or in isolated mitochondria by atomic absorption spectrophotometry. The data (plus standard deviations) are representative of at least three independent experiments. (B) Cell lysates were prepared from the indicated yeast strains, and measurements of aconitase, SDH, and MDH were obtained. One unit of enzyme activity is equivalent to 1.0 nmol of substrate converted/min/mg of protein. Substrates were cis-aconitate (aconitase), dichlorophenol indophenol (SDH), and NADH (MDH). Error bars show standard deviations. The strains used are listed in the Fig. 1 legend.

Mitochondrial [4Fe-4S] aconitase is an easily scored marker for monitoring Fe-S cluster formation or repair. The glutamate dependency of isaΔ mutants (Fig. 1B) was consistent with a defect in aconitase because aco1 mutants of yeast lacking aconitase are glutamate auxotrophs (12, 15). To address this more rigorously, aconitase activity in the isa mutants was monitored. As seen in Fig. 2B, aconitase activity was reduced to undetectable levels in the isa1Δ, isa2Δ, and isa1Δ isa2Δ strains. Evidently, the compromised growth of isaΔ strains on medium lacking glutamate results from a defect in aconitase. By comparison, the lysine growth requirement of isaΔ strains cannot be explained by a similar aconitase deficiency, since yeast aco1 mutants are not lysine auxotrophs. The lysine biosynthetic pathway in yeast utilizes a single Fe-S enzyme, a fungal specific [4Fe-4S] homoaconitase presumed to be mitochondrial in location (18, 47, 51). Although it was not possible to obtain comparative measurements of homoaconitase activity, a defect in this enzyme is a likely cause of the lysine auxotrophy. (Homoaconitase expression is induced by lysine starvation [47], and since the isa1Δ, isa2Δ, and isa1Δ isa2Δ strains are auxotrophic for lysine, it was not possible to determine the homoaconitase activity in these strains.)

An additional marker for Fe-S cluster assembly is mitochondrial SDH, which harbors three Fe-S clusters (28). As seen in Fig. 2B, the activity of SDH was reduced to negligible levels in the isa1Δ, isa2Δ, and isa1Δ isa2Δ strains. Loss of SDH and aconitase activity was consistent with a role for the Isa proteins in Fe-S cluster formation. However, the activity of MDH, which does not contain an Fe-S cluster, was also reduced in isaΔ mutants (Fig. 2B). Nevertheless, this partial inhibition of MDH activity (approximately 40% of wild-type levels) is moderate compared to the virtual abrogation of activity seen with the mitochondrial Fe-S-containing enzymes.

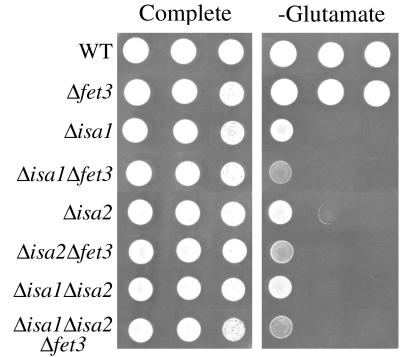

The loss of SDH and aconitase activity in isa mutants could result either from a deficiency in assembly of Fe-S centers or from Fe-related damage to the mitochondria, as has been suggested for frataxin mutants of yeast and mammals (2, 10, 35, 53). To test whether elevated iron was responsible for the isa mutant defects, the FET3 gene necessary for high-affinity iron uptake (1) was deleted in strains lacking Isa1p or Isa2p. Limiting iron through a disruption in FET3 did not reverse any of the enzymatic or growth defects associated with a loss of ISA1 or ISA2 (data not shown). Instead, reducing iron availability appeared to intensify the effects of ISA deficiency. As seen in Fig. 3, the growth requirement for glutamate in both isa1 and isa2 mutants was exacerbated by a fet3Δ mutation. It is possible that the hyperaccumulation of iron in the mitochondria serves to partially compensate for the loss of Isa1p or Isa2p.

FIG. 3.

Effects of limiting iron uptake in isa mutants. The indicated yeast strains were tested for growth by plating 105, 104, or 103 cells in 10 μl of solution onto SD medium either supplemented with (complete) or lacking glutamate and were grown for 5 days at 30°C. Strains utilized: WT, Δisa1, and Δisa2, as described in the Fig. 1 legend; Δfet3, LJ105; Δisa1 Δfet3, LJ106; Δisa2 Δfet3, LJ107; Δisa1 Δisa2 Δfet3, LJ108.

Conserved cysteine residues in Isa1p and Isa2p are critical for function.

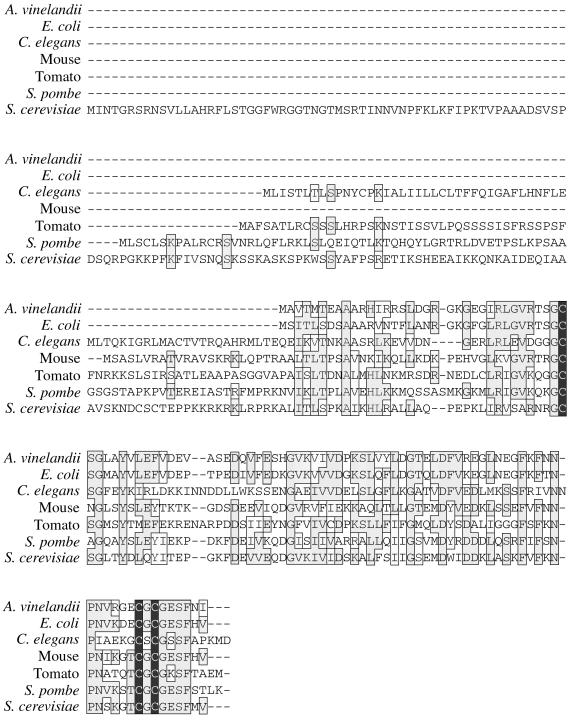

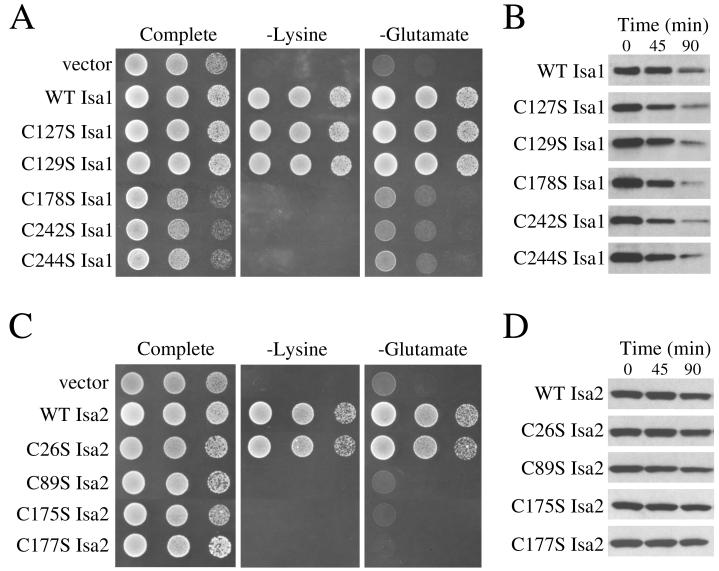

An inspection of available databases revealed the presence of numerous IscA-like proteins in eukaryotes, including mammals, worms, plants, and fungi (Fig. 4). A striking feature common to all these proteins is the positioning of three invariant cysteines in the region homologous to bacterial IscA (Fig. 4). S. cerevisiae Isa1p contains two additional cysteines that are not conserved in other species and are confined to the N-terminal leader region (Fig. 4). To test the significance of these various cysteines, each was individually replaced with a serine, and the activity of the corresponding Isa1p mutant was judged by complementation of the isa1Δ mutant. As seen in Fig. 5A, mutations introduced at the three cysteines within the IscA-like domain (residues 178, 242, and 244) resulted in nonfunctional proteins that failed to complement the lysine and glutamate growth defects of the isa1Δ strain. By comparison, analogous mutations at C127 and C129 in the N-terminal region had no effect on Isa1p activity (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 4.

Sequence comparison of IscA-like proteins from bacteria and eukaryotes. Conserved and similar residues are in boxes, and cysteine residues are indicated by black. S. cerevisiae is represented by Isa1p. Gene accession numbers for IscA homologues from higher eukaryotes: Caenorhabditis elegans, AL034488.1; mouse, AA986206; tomato, AI486638; and Schizosaccharomyces pombe, D89209.

FIG. 5.

Conserved cysteine residues are critical for Isa1p and Isa2p function. (A) The isa1Δ haploid strain was transformed either with a control vector (pLJ100) or with the pLJ100-derived plasmids that express the wild type or the indicated mutant alleles of Isa1-HA; transformants were tested for complementation of the lysine and glutamate growth defects, as for Fig. 1B. (B) The wild-type strain BY4741 was transformed with plasmids for GAL1-driven expression of the wild type or the indicated mutant variants of Isa1-HA. Cells were initially grown in the presence of galactose, followed by the addition of glucose for the indicated time points to repress gene expression. Cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-HA antibody. (C) The isa2Δ strain was transformed either with a control vector (pLJ200) or with pLJ200-derived plasmids that express the wild type or the indicated mutant variants of Isa2-HA; complementation of the isa2Δ growth defect was monitored as shown in panel A. (D) Western blot analysis of Isa2-HA expression was monitored as shown in panel B.

The accumulation of wild-type and mutant Isa1p variants was monitored by Western blotting. Initially, we failed to detect physiological levels of Isa1p using either an anti-Isa1 antibody to monitor endogenous Isa1p or an anti-HA antibody to probe a fully functional HA-tagged version of the protein (as used in Fig. 5A). Isa1p evidently accumulates to very low levels when expressed from its own promoter. However, expression of the Isa1-HA fusion by the GAL1 promoter enabled detection of the polypeptide (Fig. 5B). The cysteine-to-serine mutant variants of Isa1-HA accumulated to levels similar to those of the wild-type protein when cells were grown under nonrepressed galactose conditions. Following the addition of glucose to inhibit further protein production, the rate of disappearance of the cysteine substitution mutants was similar to that observed for wild-type Isa1-HA, demonstrating that protein stability was not affected by these mutations (Fig. 5B). Hence, the loss in complementation seen with Isa1p variants C178S, C242S, and C244S reflects a loss in Isa1p activity.

A similar analysis was conducted with Isa2p. This protein harbors the same three conserved cysteine residues in the IscA-like region yet only a single cysteine in the N-terminal sequence (Fig. 1A). A C26S mutation in the N-terminal region was without effect, and the corresponding Isa2p variant exhibited wild-type activity (Fig. 5C). By comparison, cysteine-to-serine substitutions at each of the conserved positions (89, 175, and 177) all failed to complement the lysine and glutamate growth defects (Fig. 5D). Expression of the Isa2 mutant proteins was monitored in a fashion similar to that of Isa1p (Fig. 5B), and as seen in Fig. 5D, the cysteine-to-serine substitutions did not affect the accumulation or stability of the Isa2-HA protein. However, the overall stability of Isa2p appeared to be greater than that of Isa1p, since the majority of Isa2-HA was still present following 90 min of glucose repression, at which time Isa1-HA was substantially degraded (compare Fig. 5B and 5D).

Isa1p is targeted to the mitochondrial matrix.

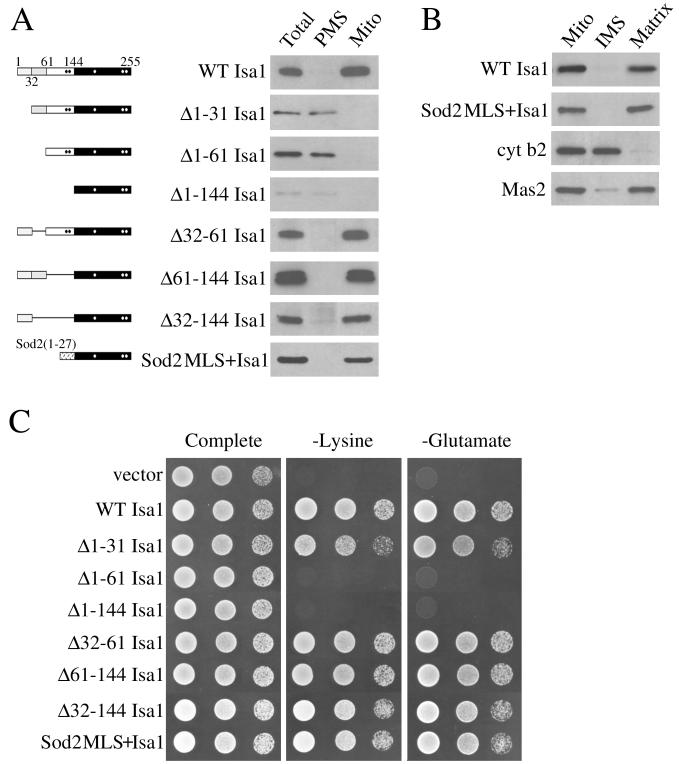

As predicted by the PSORT II program (31), the N-terminal leader region of Isa1p (residues 1 to 143) contains within the first 31 residues a putative targeting signal for the mitochondrial matrix (Fig. 1A). Cellular fractionation experiments with Isa1-HA revealed that the polypeptide is localized within the mitochondria (Fig. 6A). In addition, separation of the mitochondrial intermembrane space and matrix revealed that Isa1-HA was present in the matrix fraction as judged by colocalization with the mitochondrial processing protease Mas2 (Fig. 6B). An N-terminal truncation mutant of Isa1p was created in which the first 31 amino acids were removed, resulting in a protein (Δ1–31 Isa1) that could be detected only in the soluble postmitochondrial fraction (Fig. 6A). Unexpectedly, Isa1 Δ1–31 was partially functional in complementing the lysine and glutamate growth defects of isa1Δ mutants, although this activity represented only 10% of that of the wild-type protein, as estimated by cell dilutions (Fig. 6C). It was noted that residues 33 to 61 of Isa1p also contain many features typical of mitochondrial targeting signals (Fig. 1A), which might help direct a low or undetectable level of Δ1–31 Isa1p to the mitochondria. To address this possibility, an Isa1p variant in which both potential mitochondrial targeting sequences were removed was created. The resultant Δ1–61 Isa1 protein was exclusively localized to the postmitochondrial fraction and was completely inactive for complementation of the isa1Δ growth defect (Fig. 6A and C).

FIG. 6.

Mitochondrial localization of Isa1p is required for its function. (A, left) Schematic of the Isa1 polypeptide, where stippled areas mark predicted sequences for mitochondrial targeting and dark boxes represent the IscA homology domain. Dots indicate positions of conserved cysteines, and lines represent polypeptide sequences deleted. (A, right) The wild-type strain BY4741 was transformed with the indicated plasmids for GAL1-driven expression of the wild-type or mutant Isa1-HA. Isa1-HA proteins were allowed to accumulate in galactose-containing medium, followed by a 15-min treatment with glucose prior to preparation of cell lysates. The “Total” extract and the mitochondrial (Mito) and postmitochondrial supernatant (PMS) fractions were analyzed by Western blotting, as for Fig. 5. (B) Isolated mitochondria were separated into intermembrane space (IMS) and matrix fractions and were probed with either anti-HA, anti-cytochrome b2, or anti-Mas2 antibodies. (C) Plasmids for the expression of wild-type and mutant Isa1-HA polypeptides derived from vector pLJ100 were transformed into the isa1Δ strain and were tested for growth as described in the Fig. 1 legend.

Internal deletions within the N-terminal leader region of Isa1p were also generated, removing sequences between the mitochondrial targeting signals and the IscA-like domain of the protein. These internal deletions (Δ32–61, Δ61–144, and Δ32–144) all resulted in Isa1p variants that were exclusively localized to the mitochondria and fully complemented the isa1Δ strain (Fig. 6A and B). To confirm that Isa1p minimally requires the IscA-like region and a mitochondrial signaling sequence, the mitochondrial targeting sequence from the matrix-localized superoxide dismutase (Sod2p residues 1 to 27) was fused to Isa1p residues 144 to 255. This protein fusion was properly targeted to the mitochondrial matrix and fully reversed the lysine and glutamate growth dependencies of the isa1Δ strain (Fig. 6). These studies demonstrate that mitochondrial matrix targeting is necessary for Isa1p function, at least in supporting lysine- and glutamate-independent growth.

Isa2p is present in the mitochondrial intermembrane space.

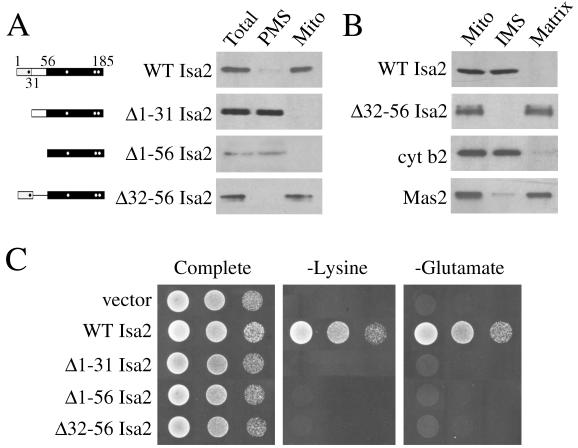

Compared to the long leader region of Isa1p (144 residues), Isa2p has a short sequence upstream of the IscA homology domain (56 residues). As predicted by the PSORT II program (31), a potential sequence for mitochondrial targeting occurs with the first 31 residues of the protein, followed by an additional 25 amino acids that could not be fitted to any consensus sequence (Fig. 1A). Isa2p was detected in mitochondrial fractions, and deletion of the predicted mitochondrial targeting sequence (Δ1–31 Isa2p) and a more extensive deletion mutation (Δ1–56 Isa2p) resulted in proteins which were both excluded from the mitochondria and devoid of activity as monitored by complementation of the isa2Δ growth defects (Fig. 7A and C). This confirms that residues 1 to 31 of Isa2p contain the mitochondrial targeting activity.

FIG. 7.

Isa2p localizes to the mitochondrial intermembrane space. (A, left) Schematic of the Isa2 polypeptide, as described in the Fig. 6 legend for Isa1p. (A, right) Western blot analysis of Isa2-HA expression, as described in the Fig. 6A legend for Isa1p. (B) Mitochondria were fractionated and analyzed as described in the Fig. 6B legend. (C) Plasmids for the expression of wild-type and mutant Isa2-HA polypeptides derived from vector pLJ200 were transformed into the isa1Δ strain and tested for growth as described in the Fig. 1 legend.

Separation of the mitochondria into intermembrane space and matrix fractions revealed that Isa2-HA colocalized with cytochrome b2 and was present in the mitochondrial intermembrane space (Fig. 7B). The unexpected localization of Isa2p to the mitochondrial intermembrane space appears to involve sequences spanning residues 32 to 56. When this region was deleted, the resultant Δ32–56 Isa2 protein was targeted to the mitochondria but present in the matrix fraction (Fig. 7A and B). However, this matrix-localized Isa2p was completely inactive for complementation of the isa2Δ mutant (Fig. 7C).

These results demonstrate that unlike Isa1p, Isa2p requires the entire N-terminal leader region for function. Furthermore, this region can be divided into two functionally distinct sequences: a matrix-targeting sequence at the extreme N terminus and an adjacent peptide of 25 amino acids that appears to act as a sorting signal, directing Isa2p to the mitochondrial intermembrane space.

DISCUSSION

The results presented here provide strong evidence that S. cerevisiae Isa1p and Isa2p play important roles in iron metabolism, particularly in the assembly or repair of Fe-S clusters. These proteins exhibit striking homology to bacterial IscA of the isc operon for Fe-S cluster assembly (55). Similar to what has been observed for the yeast ATM1, SSQ1, NFS1, NFU1, YAH1, and ISU genes proposed to function in Fe-S metabolism (13, 21, 23, 25, 26, 39), a deletion in ISA1 or ISA2 results in elevated levels of mitochondrial iron. The high iron content of the mitochondria is likely to cause oxidative damage to this organelle, and as one consequence, isa1Δ and isa2Δ mutants accumulate mutations in mitochondrial DNA. Additionally, these mutants exhibit a partial reduction in activity of mitochondrial MDH, which might also reflect damage to the mitochondria. In comparison to the partial inhibition of MDH, activities of Fe-S enzymes (e.g., aconitase and SDH) are virtually eliminated in cells lacking Isa1p and Isa2p, as would be expected for strains deficient in assembly and/or repair of Fe-S clusters.

While an increase in reactive oxygen species due to high mitochondrial iron may be damaging to Fe-S-containing enzymes, this cannot fully explain the defects of isa1Δ and isa2Δ mutants. First, S. cerevisiae mutants lacking ATM1 accumulate high levels of iron in the mitochondria yet show no defects in aconitase or SDH activity (21). Furthermore, inhibiting cellular iron uptake in isa mutants failed to reverse the Fe-S enzyme defects of these strains. In fact, limiting cellular iron appeared to exacerbate the aconitase deficiency of isa1 and isa2 mutants. Perhaps in the isa mutants, high mitochondrial iron is somewhat beneficial and partially compensates by elevating pools of available iron to increase the frequency of spontaneous cluster formation.

Although the precise functions of Isa1p and Isa2p remain unknown, a likely explanation is that these proteins act as donors of iron for the assembly of Fe-S clusters. Both proteins contain three invariant cysteines that are conserved among IscA-like proteins from bacteria, fungi, plants, and mammals. Our mutagenesis studies revealed that all three cysteines are essential for Isa1p and Isa2p function. It is conceivable that these three cysteines constitute an iron-binding motif. In accordance with this, we noted that the purified IscA-like region of Isa1p binds iron in vitro (L. T. Jensen and V. C. Culotta, unpublished data).

A key question in the area of Fe-S center biogenesis regards the site of cluster assembly. Work in the laboratory of T. Rouault has demonstrated that mammalian NifS (equivalent to yeast Nfs1p) is distributed among mitochondrial and cytosolic locations (24). However, in yeast, all the Isc-like proteins previously studied appear to be mitochondrion specific (13, 21, 25, 26, 38, 39). We demonstrate here that Isa1p is present in the mitochondrial matrix and is functional only when localized there. Surprisingly, Isa2p was not detected in the mitochondrial matrix but was found within the mitochondrial intermembrane space. It appears that Isa2p is directed to the intermembrane space by the action of a second peptide in the N-terminal leader, adjacent to the mitochondrial targeting sequence. The two-domain leader region of Isa2p is reminiscent of the bipartite presequence of cytochrome b2, containing separate signals for sorting to the mitochondrial matrix and the inner membrane space (16, 40). In the case of Isa2p, we find that both the matrix-targeting and intermembrane sorting signals are necessary for its activity.

Based on these findings, we propose a model for the action of Isa1p and Isa2p. Our studies strongly indicate that these proteins are not redundant, as there are no additive effects of combining isa1 and isa2 mutations. Presumably, these proteins work in concert, either in a linear pathway or together as part of a complex to deliver iron to the site of Fe-S cluster biogenesis. The Isa proteins are not required for bulk mitochondrial iron uptake, as seen by the hyperaccumulation of mitochondrial iron in the isaΔ strains. This hyperaccumulated iron does not appear to be in a form available to Fe-S-containing enzymes. Instead, the Isa proteins may act in the trafficking of iron within the mitochondria. Since Isa2p is located within the mitochondrial intermembrane space, Isa2p may act in the stepwise delivery of mitochondrial iron to the matrix, perhaps via a metal transporter in the inner membrane. Inside the mitochondrial matrix, Isa1p may have a more direct role in the assembly of Fe-S clusters by acting as an iron donor. Alternatively, the metal carried by Isa1p or Isa2p may be delivered to the Isu1 and Isu2 proteins in the mitochondrion, which are also proposed metal donors for Fe-S cluster assembly (13, 39, 54). In any case, the insertion of iron into metal clusters in vivo is predicted to require specific metal-binding factors. In cell-free systems, Fe-S centers can be assembled using simple iron salts (9, 17, 46), but free iron atoms are not likely to accumulate in living cells due to the highly toxic nature of these ions. Analogous to what has been shown for copper (3, 6, 33, 34, 48), the delivery of iron to active sites in the cell is expected to require a family of iron metallochaperones, and Isa1p and Isa2p may serve as examples.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to K. Yu and J. Boeke for generating the isa1Δ strain and for noting the lysine auxotrophy associated with this mutant. We also thank J. Boeke for critical review of the manuscript, L. Vickery and R. Jensen for helpful discussions and for the cytochrome b2 and Mas2 antibodies, and A. Dancis for the fet3::URA3 plasmid.

This work was supported by the JHU NIEHS center and by NIH grant GM 50016 to V.C.C. L.T.J. was supported by NIEHS training grant ES 07141.

ADDENDUM IN PROOF

In a recent study by Lill and colleagues (A. Kaut, H. Lang, K. Diekert, G. Kispal, and R. Lill, J. Biol. Chem., in press) S. cerevisiae Isa1p was shown to be important for mitochondrial iron metabolism.

REFERENCES

- 1.Askwith C, Eide D, Van Ho A, Bernard P S, Li L, Davis-Kaplan S, Sipe D M, Kaplan J. The FET3 gene of S. cerevisiae encodes a multicopper oxidase required for ferrous iron uptake. Cell. 1994;76:403–410. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90346-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babcock M, de Silva D, Oaks R, Davis-Kaplan S, Jiralerspong S, Montermini L, Pandolfo M, Kaplan J. Regulation of mitochondrial iron accumulation by Yfh1p, a putative homolog of frataxin. Science. 1997;276:1709–1712. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5319.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beers J, Glerum D M, Tzagoloff A. Purification, characterization, and localization of yeast Cox17p, a mitochondrial copper shuttle. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:33191–33196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.33191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beinert H, Kennedy M C. Aconitase, a two-faced protein: enzyme and iron regulatory factor. FASEB J. 1993;7:1442–1449. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.15.8262329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brachmann C B, Davies A, Cost G J, Caputo E, Li J, Hieter P, Boeke J D. Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: a useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast. 1998;14:115–132. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19980130)14:2<115::AID-YEA204>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casareno R L, Waggoner D, Gitlin J D. The copper chaperone CCS directly interacts with copper/zinc superoxide dismutase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23625–23628. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.23625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cullin C, Minvielle-Sebastia L. Multipurpose vectors designed for the fast generation of N- or C-terminal epitope-tagged proteins. Yeast. 1994;10:105–112. doi: 10.1002/yea.320100110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daum G, Bohni P C, Schatz G. Import of proteins into mitochondria. Cytochrome b2 and cytochrome c peroxidase are located in the intermembrane space of yeast mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:13028–13033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flint D H. Escherichia coli contains a protein that is homologous in function and N-terminal sequence to the protein encoded by the nifS gene of Azotobacter vinelandii and that can participate in the synthesis of the Fe-S cluster of dihydroxy-acid dehydratase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:16068–16074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foury F, Cazzalini O. Deletion of the yeast homologue of the human gene associated with Friedreich's ataxia elicits iron accumulation in mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 1997;411:373–377. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00734-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu W, Jack R F, Morgan T V, Dean D R, Johnson M K. nifU gene product from Azotobacter vinelandii is a homodimer that contains two identical [2Fe-2S] clusters. Biochemistry. 1994;33:13455–13463. doi: 10.1021/bi00249a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gangloff S P, Marguet D, Lauquin G J-M. Molecular cloning of the yeast mitochondrial aconitase gene (ACO1) and evidence of a synergistic regulation of expression by glucose plus glutamate. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:3551–3561. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.7.3551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garland S, Hoff K, Vickery L, Culotta V. Saccharomyces cerevisiae ISU1 and ISU2: members of a well-conserved gene family for iron-sulfur cluster assembly. J Mol Biol. 1999;294:897–907. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gietz R D, Schiestl R H. Applications of high efficiency lithium acetate transformation of intact yeast cells using single-stranded nucleic acids as carrier. Yeast. 1991;7:253–263. doi: 10.1002/yea.320070307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez A, Rodriguez L, Olivera H, Soberon M. NADP+-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase activity is impaired in mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae that lack aconitase. J Gen Microbiol. 1985;131:2565–2571. doi: 10.1099/00221287-131-10-2565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartl F U, Ostermann J, Guiard B, Neupert W. Successive translocation into and out of the mitochondrial matrix: targeting of proteins to the intermembrane space by a bipartite signal peptide. Cell. 1987;51:1027–1037. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90589-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hidalgo E, Demple B. Activation of SoxR-dependent transcription in vitro by noncatalytic or NifS-mediated assembly of [2Fe-2S] clusters into apo-SoxR. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7269–7272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Irvin S D, Bhattacharjee J K. A unique fungal lysine biosynthesis enzyme shares a common ancestor with tricarboxylic acid cycle and leucine biosynthetic enzymes found in diverse organisms. J Mol Evol. 1998;46:401–408. doi: 10.1007/pl00006319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobson M R, Cash V L, Weiss M C, Laird N F, Newton W E, Dean D R. Biochemical and genetic analysis of the nifUSVWZM cluster from Azotobacter vinelandii. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;219:49–57. doi: 10.1007/BF00261156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kispal G, Csere P, Guiard B, Lill R. The ABC transporter Atm1p is required for mitochondrial iron homeostasis. FEBS Lett. 1997;418:346–350. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01414-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kispal G, Csere P, Prohl C, Lill R. The mitochondrial proteins Atm1p and Nfs1p are essential for biogenesis of cytosolic Fe/S proteins. EMBO J. 1999;18:3981–3989. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.14.3981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klausner R D, Rouault T A, Harford J B. Regulating the fate of mRNA: the control of cellular iron metabolism. Cell. 1993;72:19–28. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90046-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knight S A, Sepuri N B, Pain D, Dancis A. Mt-Hsp70 homolog, Ssc2p, required for maturation of yeast frataxin and mitochondrial iron homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18389–18393. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Land T, Rouault T A. Targeting of a human iron-sulfur cluster assembly enzyme, nifs, to different subcellular compartments is regulated through alternative AUG utilization. Mol Cell. 1998;2:807–815. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80295-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lange H, Kaut A, Kispal G, Lill R. A mitochondrial ferredoxin is essential for biogenesis of cellular iron-sulfur proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1050–1055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li J, Kogan M, Knight S A, Pain D, Dancis A. Yeast mitochondrial protein, Nfs1p, coordinately regulates iron-sulfur cluster proteins, cellular iron uptake, and iron distribution. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33025–33034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.46.33025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu X F, Culotta V C. Post-translation control of Nramp metal transport in yeast. Role of metal ions and the BSD2 gene. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4863–4868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.4863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lombardo A, Carine K, Scheffler I E. Cloning and characterization of the iron-sulfur subunit gene of succinate dehydrogenase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:10419–10423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McAlister-Henn L, Thompson L M. Isolation and expression of the gene encoding yeast mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:5157–5166. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.11.5157-5166.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mumberg D, Muller R, Funk M. Yeast vectors for the controlled expression of heterologous proteins in different genetic backgrounds. Gene. 1995;156:119–122. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakai K, Horton P. PSORT: a program for detecting sorting signals in proteins and predicting their subcellular localization. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:34–36. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01336-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phillips J D, Guo B, Yu Y, Brown F M, Leibold E A. Expression and biochemical characterization of iron regulatory proteins 1 and 2 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemistry. 1996;35:15704–15714. doi: 10.1021/bi960653l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pufahl R A, Singer C P, Peariso K L, Lin S J, Schmidt P J, Fahrni C J, Culotta V C, Penner-Hahn J E, O'Halloran T V. Metal ion chaperone function of the soluble Cu(I) receptor Atx1. Science. 1997;278:853–856. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rae T D, Schmidt P J, Pufahl R A, Culotta V C, O'Halloran T V. Undetectable intracellular free copper: the requirement of a copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase. Science. 1999;284:805–808. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rotig A, de Lonlay P, Chretien D, Foury F, Koenig M, Sidi D, Munnich A, Rustin P. Aconitase and mitochondrial iron-sulphur protein deficiency in Friedreich ataxia. Nat Genet. 1997;17:215–217. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rouault T, Klausner R. Regulation of iron metabolism in eukaryotes. Curr Top Cell Regul. 1997;35:1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2137(97)80001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rouault T A, Haile D J, Downey W E, Philpott C C, Tang C, Samaniego F, Chin J, Paul I, Orloff D, Harford J B, et al. An iron-sulfur cluster plays a novel regulatory role in the iron-responsive element binding protein. Biometals. 1992;5:131–140. doi: 10.1007/BF01061319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schilke B, Forster J, Davis J, James P, Walter W, Laloraya S, Johnson J, Miao B, Craig E. The cold sensitivity of a mutant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae lacking a mitochondrial heat shock protein 70 is suppressed by loss of mitochondrial DNA. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:603–613. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.3.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schilke B, Voisine C, Beinert H, Craig E. Evidence for a conserved system for iron metabolism in the mitochondria of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10206–10211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwarz E, Seytter T, Guiard B, Neupert W. Targeting of cytochrome b2 into the mitochondrial intermembrane space: specific recognition of the sorting signal. EMBO J. 1993;12:2295–2302. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05883.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seaton B L, Vickery L E. A gene encoding a DnaK/hsp70 homolog in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2066–2070. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sherman F, Fink G R, Lawrence C W. Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sikorski R S, Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silberg J J, Hoff K G, Vickery L E. The Hsc66-Hsc20 chaperone system in Escherichia coli: chaperone activity and interactions with the DnaK-DnaJ-GrpE system. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6617–6624. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6617-6624.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strain J, Lorenz C R, Bode J, Garland S, Smolen G A, Ta D T, Vickery L E, Culotta V C. Suppressors of superoxide dismutase (SOD1) deficiency in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Identification of proteins predicted to mediate iron-sulfur cluster assembly. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:31138–31144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.47.31138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trumpower B L, Edwards C A. Purification of a reconstitutively active iron-sulfur protein (oxidation factor) from succinate · cytochrome c reductase complex of bovine heart mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:8697–8706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Urrestarazu L A, Borell C W, Bhattacharjee J K. General and specific controls of lysine biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet. 1985;9:341–344. doi: 10.1007/BF00421603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Valentine J S, Gralla E B. Delivering copper inside yeast and human cells. Science. 1997;278:817–818. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vickery L E, Silberg J J, Ta D T. Hsc66 and Hsc20, a new heat shock cognate molecular chaperone system from Escherichia coli. Protein Sci. 1997;6:1047–1056. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wach A, Brachat A, Pohlmann R, Philippsen P. New heterologous modules for classical or PCR-based gene disruptions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1994;10:1793–1808. doi: 10.1002/yea.320101310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weidner G, Steffan B, Brakhage A A. The Aspergillus nidulans lysF gene encodes homoaconitase, an enzyme involved in the fungus-specific lysine biosynthesis pathway. Mol Gen Genet. 1997;255:237–247. doi: 10.1007/s004380050494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Winzeler E A, Shoemaker D D, Astromoff A, Liang H, Anderson K, Andre B, Bangham R, Benito R, Boeke J D, Bussey H, Chu A M, Connelly C, Davis K, Dietrich F, Dow S W, El Bakkoury M, Foury F, Friend S H, Gentalen E, Giaever G, Hegemann J H, Jones T, Laub M, Liao H, Davis R W, et al. Functional characterization of the S. cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis. Science. 1999;285:901–906. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5429.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wong A, Yang J, Cavadini P, Gellera C, Lonnerdal B, Taroni F, Cortopassi G. The Friedreich's ataxia mutation confers cellular sensitivity to oxidant stress which is rescued by chelators of iron and calcium and inhibitors of apoptosis. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:425–430. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.3.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yuvaniyama P, Agar J N, Cash V L, Johnson M K, Dean D R. NifS-directed assembly of a transient [2Fe-2S] cluster within the NifU protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:599–604. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zheng L, Cash V L, Flint D H, Dean D R. Assembly of iron-sulfur clusters. Identification of an iscSUA-hscBA-fdx gene cluster from Azotobacter vinelandii. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13264–13272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zheng L, Dean D R. Catalytic formation of a nitrogenase iron-sulfur cluster. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:18723–18726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zheng L, White R H, Cash V L, Jack R F, Dean D R. Cysteine desulfurase activity indicates a role for NIFS in metallocluster biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2754–2758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]