Abstract

Background

Management of patients in intensive care units (ICUs) needs staff with a recommended level of expertise and experience owing to the life-threatening nature of illnesses, injuries and complications that these patients present with. There are no specific guidelines governing physiotherapy practice in ICUs in Nigeria. Hence, there is a need to have expert consensus on the minimum clinical standard of practice for physiotherapists working in ICUs as a first step to proposing/developing guidelines in the future.

Objectives

To assess the expert consensus on the minimum clinical standard of practice for physiotherapists working in ICUs in Nigeria.

Methods

Physiotherapists with working experience in Nigerian ICUs were purposively recruited into the present study using a modified Delphi technique. A questionnaire comprising 222 question items on the role of physiotherapy in critical care was adopted and administered to the participants over three rounds of Delphi procedure (online). Participants checked either ‘essential’, ‘not essential’ or ‘unsure’ for each question item. For each question item to be considered ‘essential’ or ‘not essential’, a consensus agreement ≥70% had to be met. Questions without consensus were further modified by providing definition or clarification and presented in subsequent rounds. Data were analysed descriptively.

Results

We recruited 26 expert physiotherapists who consented to the study and completed the first round of the study. The majority of the physiotherapists (n=24) remained in the study after the third round. A total of 178 question items were adjudged to be ‘essential’ after the first round, and a further 15 and three additional items were subsequently adjudged to be as ‘essential’ after modifying the outstanding question items during the second and third rounds, respectively. No consensus was reached for 24 items. None of the question items were ranked as ‘not essential’ after all the rounds.

Conclusion

Expert consensus was achieved for a substantial number of question items regarding knowledge and skills for assessment, condition and treatment items of the questionnaire by experienced critical care physiotherapists in Nigeria.

Keywords: expert consensus, critical care physiotherapy, Delphi technique, standards of practice

Background

Intensive care units (ICUs) are specially staffed and equipped hospital wards for management of patients with life-threatening illnesses, injuries or complications. However, the range to which different hospitals provide services to critically ill patients depends on the skills, expertise, facilities and clinical specialties available in the hospitals.[1] Physiotherapy is one of the fundamental interventions administered to patients in ICU.[2] The major goals of physiotherapy in the ICU include maintaining/restoring the general patient’s functional capacity, and restoring respiratory and physical independence. Physiotherapy also helps to decrease the risks associated with stay in the ICU such as acquired muscle weakness, physical deconditioning and poor quality of life.[3] Moreover, the positive impact of physiotherapy in the management of patients whose conditions require critical care is well documented[4,5] and noted to improve survival rates.[6] There is moderate-to-strong evidence to support the role of physiotherapy for managing critically ill patients.[7]

The ICUs in resource-restricted settings have limited infrastructure, materials and human resources.[8] In the UK, just as in other developed countries, physiotherapy is provided for 24 hours/day and 7 days a week (including on-call and public holidays) for patients in the ICUs.[7] In Nigeria, ICU patients are managed by physiotherapists every day of the week, but no evidence exists to support whether this is actually instituted in the ICUs standard of practice or guidelines. Consequently, some fresh graduate physiotherapists may start their first on-call service with less or no previous hands-on experience or training in managing critically ill patients in some ICUs.[9] Some centres compensate for this inadequacy by organising in-house/local critical care programmes/ICU workshops or mentoring to solve the problems of novice physiotherapists working in the ICU. Nevertheless, a bachelor’s degree remains the least requirement for physiotherapists to work in ICUs in Nigeria. In short, the quality of care provided in the ICU largely depends on the skills of the attending physiotherapist.

Previous modified Delphi studies by Skinner et al.[10] in Australia, Twose et al.[11] in the UK and Takahashi et al [12] in Japan identified 132, 107 and 199, respectively, question items that are considered ‘essential’ for physiotherapists working in critical care units, and form a 222-item questionnaire developed by Skinner et al.[10] A similar study using the same questionnaire is necessary in Nigeria to identify and possibly suggest ways to standardise the competencies of physiotherapy practice in ICUs. As no standards of practice currently exist for the training of physiotherapists working in critical care in Nigeria and adopting an existing questionnaire has precedence in Delphi methodology.[13] Using the questionnaire developed by Skinner et al. [10] offered us the opportunity to contextualise our findings using a global point of view. Moreover, ICU patients require the best care possible, irrespective of the setting. The absence of national treatment guidelines indicates that most ICU interventions in resource-limited settings are often based upon treatment guidelines adopted from developed countries or international stakeholders.

The development of critical care in resource-poor settings relies on service improvements, including leveraging human resources through training, a focus on sustainable technology, continuous analyses of cost effectiveness and sharing of context-specific best practices.[14] Therefore, the present study is designed to explore the consensus of experienced physiotherapists regarding the minimum clinical standards of practice that physiotherapists working in critical care in our environment should possess. Moreover, the findings from this study could help in focusing future treatment guidelines, postgraduate education and ICU-related training of critical care physiotherapists in Nigeria and other similar countries.

Method

The present study followed a guide for Conducting and REporting of DElphi Studies (CREDES).[15]

Ethics

Ethical approval was sought and obtained from the Research and Ethical Committee of the College of Health Sciences, Bayero University, Kano (ref. no. NHREC/06/12/19/22). The ethical protocols of the Declaration of Helsinki including the ethical principles of informed consent, privacy and confidentiality of data provided were followed in the Delphi rounds.

Design

A modified Delphi technique was used to seek consensus on the minimum standards of practice for physiotherapists working in ICUs in Nigeria. Delphi techniques using online surveys are easily accessible and were the most appropriate for this study because they allow participants from across Nigeria to take part in the study from start to finish.[16,17] In addition, the Delphi technique allows for formation of consensus or exploration of a field beyond existing knowledge. It can be adapted to the particular requirements of the research question, and it takes the form of open and exploratory questions to standardised confirmatory approaches.[15] In the present study, the basic Delphi technique was modified to allow for question clarification, addition of new items and eventual agreement of the items by participants. Furthermore, in the second and third rounds of the Delphi study, additional definitions with examples (where possible) were provided for some terminologies where consensus was not reached in the first round to further enhance understanding of the terms.

Respondents

The prospective participants for this study were recruited using purposive sampling, alongside a snowballing method via advertisement through the official communication channels of the physiotherapy practice regulatory board and professional associations in Nigeria: namely (i) Medical Rehabilitation Therapist Registration Board of Nigeria (MRTB); (ii) Nigeria Society of Physiotherapy; and (iii) Association of Clinical and Academic Physiotherapists of Nigeria. Participants’ recruitment was also made via social media platforms, particularly WhatsApp and Facebook groups of professional associations (e.g. Nigerian physiotherapists). Eligibility criteria were only communicated to participants after they had accepted an invitation to participate in the present study.

Sample size was not fixed so that we would be able to recruit as many participants as possible who met the eligibility criteria. The eligibility criteria for participation included the following: (i) physiotherapists with a minimum of 5 years’ working experience, three of which must be in a senior role within the critical care setting; (ii) physiotherapists involved in the supervision or teaching of physiotherapy staff working on-call or completing emergency duty; and (iii) academic physiotherapy staff involved in the provision of entry-level cardio-respiratory physiotherapy with at least two articles published in the area of critical care.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire utilised in the present study was adopted from Skinner et al.[10] The questionnaire was structured and planned content-wise to be as extensive as possible across the physiotherapy role in critical care.[10] We did not pilot the questionnaire because it had been previously used in multiple studies [11] and we also aimed to contextualise the opinions of experienced physiotherapists in comparison with those in previous studies. Twose et al.[11] also adopted and used the same questionnaire without piloting. The questionnaire further highlighted that the motive of the present study was to determine the minimum standard of clinical practice that should be expected from physiotherapists to qualify them to work autonomously and safely with patients in critical care settings. The questionnaire consisted of 222 question items. For each question item, participants were asked to either check ‘essential’, ‘not essential’, or ‘unsure’ option. Respondents were also asked to submit additional items that were not previously included if they thought it necessary and essential for inclusion in the first round.

Procedure

Three rounds of questionnaire administration were sent to the study participants between 10 August 2020 and 2 October 2020, with each round lasting an average of 2 weeks. Delbecq et al.[18] recommended that 2 weeks is enough for Delphi participants to attempt each round. The study questionnaires were administered using Google forms via WhatsApp or email. The participants’ information sheets were included in the invitation message. Reminders (phone calls, SMS and WhatsApp messages) were also sent to non-responders 7 days and a day before the deadline. Participants were also assured of the anonymity of all information provided so that they would not be afraid to admit their knowledge or lack of knowledge on any question item. Moreover, the participants were not asked to provide their names or any identifiers that might link them to any information provided. Demographic variables were only collected during round one, and were analysed separately by a blinded author (ASD). On completion of each round, participants were sent a personalised message thanking them and requesting for their co-operation in the subsequent rounds.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using descriptive statistics. Since demographic data were collected in the first round only, the data were summarised as a mean with standard deviation (SD), frequencies and percentages using Microsoft Excel. For each question item, a consensus to determine if such a question item was either ‘essential’ or ‘not essential’ was based on a consensus agreement of ≥70%. A study by the original developers of the instrument recommended a threshold of 70%.[10] Therefore, this threshold was used in the present study to allow for comparison of the study findings later. The percentage of ‘unsure’ responses was also taken into consideration to determine whether consensus was reached. Specifically, consensus for each item was calculated by subtracting the number of ‘unsure’ responses from the percentage of ‘essential’ responses. For example, if an item ranked 74% as ‘essential’ and the percentage of ‘unsure’ responses was 9%, then the percentage of ‘unsure’ responses was removed from that of ‘essential’. For any item to be considered as ‘essential’ or ‘not essential’, consensus had to be >70% in any of the three rounds.

Results

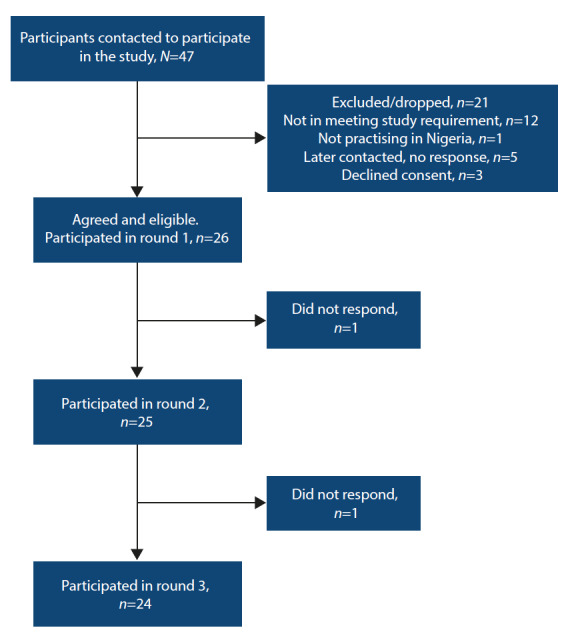

A panel of 47 experts (experienced physiotherapists working in Nigerian ICUs) responded to our invitation to participate in the Delphi study, and 32 potential participants met the inclusion criteria and were invited to participate in the first round of the present study. However, 81.3% (n=26) of the participants completed the consent forms and participated in the first round of the present study. Three-quarters of the participants (75%; n=24) remained by the end of the third round (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the recruitment and Delphi process.

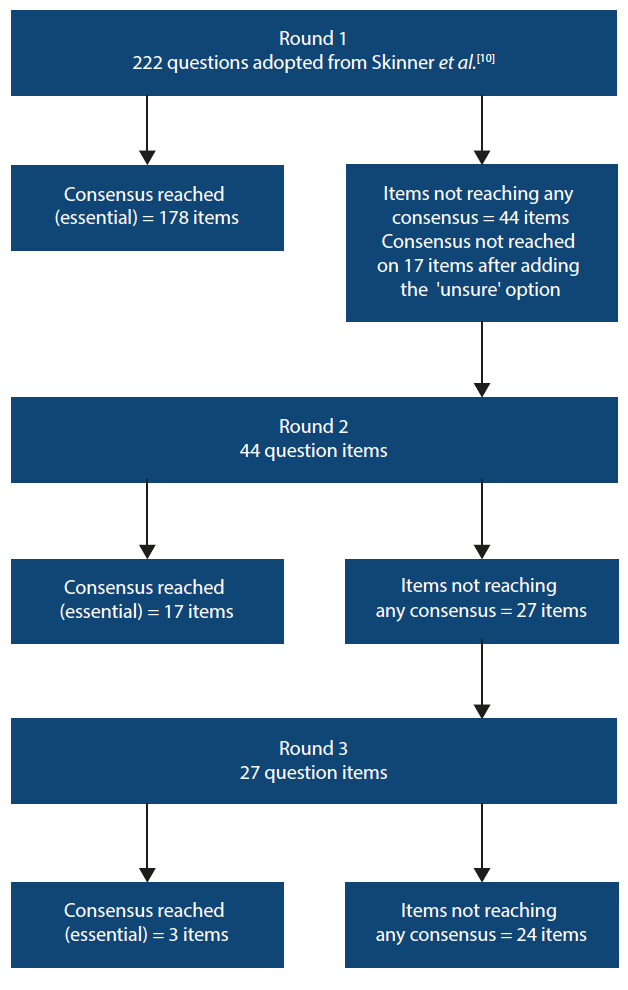

Fig. 2.

Flow of items through the three rounds of the Delphi process.

The participants comprised physiotherapy clinicians (n=24) and academics (n=2). The participants were drawn from all the six geopolitical regions of Nigeria (North East (n=4), North Central (n=5), North West (n=9), South East (n=4), South-South (n=1) and South West (n=3)). The majority of the participants (61.5%) had 10 years’ or more ICU work-related experience. A substantial number of them (n=19) were staff of federal tertiary hospitals (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographics of the experts that participated in the Delphi study (n=26).

| Characteristics | Participants, n (%)* |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 40.8 (8.6) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 16 (61.5) |

| Female | 10 (38.5) |

| Institution of practice | |

| University hospitals | 18 (69.2) |

| University academics | 2 (7.7) |

| Medical centre | 1 (3.8) |

| Specialist hospitals | 3 (11.6) |

| Private hospitals | 2 (7.7) |

| Years of experience in ICU | |

| 5 - 10 | 10 (38.5) |

| 10 - 15 | 5 (19.2) |

| 15 - 20 | 6 (23.1) |

| >20 | 5 (19.2) |

| Published article | |

| <2 | 17 (85.0) |

| 2 - 6 | 3 (15.0) |

ICU = intensive care unit

SD = standard deviation

*Unless otherwise specified

The first round of the study consisted of 222 items, of which 178 were considered as ‘essential’ by the respondents. One additional item was suggested by one participant; however, it was not added in the second round because it was a duplicate of an existing question item. None of the question items qualified to be ranked as ‘not essential’ in the first round, and consensus was not reached on 17 items on account of ‘unsure’ responses. In the end, the remaining 44 items were presented again in the second round.

Following the second round, 17 additional items were ranked as ‘essential’ and consensus was reached for 27 items. Still, no item was ranked as ‘not essential’, and no additional item was suggested by the participants in the second round. The remaining 27 question items were further presented in the third round. Consensus was only reached for 3 question items that were categorised as ‘essential’. Consequently, consensus was not reached for the remaining 24 items. Just like in rounds 1 and 2, no question item was ranked as ‘not essential’ in the third round.

Overall, the participants reached consensus on 197 items as ‘essential’ after three rounds. While no items were considered ‘not essential’, no consensus was reached for 24 items. Detailed breakdown of the question items that reached consensus following the Delphi rounds are presented in Tables 2, 3 and 4. The question items that did not reach consensus after the third round are presented in Table 5.

Table 2. Assessment items determined as essentials (consensus >70% ‘essential’).

| Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 | |

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can accurately interpret readings from clinical monitoring including: | |||

| Body temperature | 100 | ||

| Heart rate | 100 | ||

| Blood pressure | 100 | ||

| Basic ECGs, SpO2/pulse oximetry | 100 | ||

| End tidal carbon dioxide | 96.2 | ||

| Fluid intake and output | 100 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can understand equipment (including recognition of equipment) and understand the implications for physiotherapy of: | |||

| Oxygen therapy devices | 100 | ||

| Endotracheal tubes and tracheostomy | 92.3 | ||

| Central venous catheters | 88.5 | ||

| Arterial lines | 96.2 | ||

| Venous blood gas interpretation (including SvO2) Vascath/haemodialysis catheter/continuous veno-venous. |

61.5† | 88 | |

| Intercostal catheters | 84.6 | ||

| Wound drains | 80.8 | ||

| Indwelling urinary catheter | 100 | ||

| Nasogastric tubes | 100 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can accurately interpret findings from laboratory investigations including: | |||

| Haemoglobin | 100 | ||

| Platelets, APTT, INR | 92.3 | ||

| White cell count | 88.5 | ||

| Blood glucose levels | 100 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist is aware of the actions and implications for physiotherapy of the following medications: | |||

| Vasopressors/inotropes | 84.6 | ||

| Basic electrolytes | 100 | ||

| Anti-hypertensives | 92.3 | ||

| Anti-arrhythmia | 100 | ||

| Sedation and neuromuscular paralysing agents | 61.5* | 92 | |

| Bronchodilators | 92.3 | ||

| Mucolytics | 69.3* | 92 | |

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can independently interpret findings from imaging investigations (excluding the imaging report) including: | |||

| Chest radiographs | 96.2 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can interpret the results from neurological equipment/examinations and functional tests including: | |||

| Intra-cranial and cerebral perfusion pressure monitors | 96.2 | ||

| An ability to interpret an assessment of sedation levels (e.g. Ramsey Sedation Scale, Riker, Richmond-Agitation Sedation Scale) | 84.6 | ||

| An ability to perform a neurological examination of motor and sensory functions (e.g. light touch, pain) e.g. ASIA score | 100 | ||

| An ability to interpret a Glasgow Coma Score | 100 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can perform and accurately interpret the results of common respiratory examinations including: | |||

| Observation of respiratory rate | 100 | ||

| Patterns of breathing | 96.2 | ||

| Palpate the chest wall | 100 | ||

| Auscultation | 100 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist understands the key principles of providing the following differing modes of mechanical/assisted ventilation including: | |||

| CPAP | 92.3 | ||

| PEEP/EPAP | 96.2 | ||

| SIMV (volume)/(pressure) | 69.2* | 92 | |

| BiLevel | 46.2* | 88 | |

| PS/IPAP | 92.3 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can assess and interpret mechanical ventilation settings/measurements including: | |||

| Respiratory rate | 96 | ||

| Peak inspiratory pressure | 92.3 | ||

| Inspiration: expiration ratio | 100 | ||

| Tidal volume | 100 | ||

| Breath types (spontaneous, mandatory, assisted) | 100 | ||

| The levels of FiO2 | 100 | ||

| The levels of PEEP | 100 | ||

| The levels of PS | 88.5 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can: | |||

| Assess the effectiveness/quality of a patient’s cough | 100 | ||

| Record and interpret observations from physical clinical examination | |||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can interpret indices from blood-gas measurement including: | |||

| pH | 100 | ||

| PaCO2 | 100 | ||

| PaO2, SpO2, SaO2 | 100 | ||

| HCO3 | 100 | ||

| Base excess | 92.3 | ||

| P50 | 65.4† | 92 | |

| A physiotherapist can complete musculoskeletal and/or functional assessments including: | |||

| Manual muscle testing | 69.2* | 84 | |

| Range of motion | 84.6 | ||

| Deep-vein thrombosis screening | 100 | ||

| Peripheral oedema | 92.3 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can understand equipment (including recognition of equipment) and understands the implications for physiotherapy of: | |||

| Extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation | 69.2* | 80 | |

| Intracranial pressure monitors and extra-ventricular drains | 96.2 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can accurately interpret readings from clinical monitoring including: | |||

| Advanced ECGs | 80.8 | ||

| Nutritional status including feed administration, volume and type | 61.5* | 100 | |

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can accurately interpret findings from laboratory investigations including: | |||

| Haematocrit | 96.2 | ||

| Creatinine kinase | 96.2 | ||

| Neutrophil count | 92.3 | ||

| Albumin | 92.3 | ||

| Liver function tests | 88.5 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist is aware of the actions and implications for physiotherapy of the following medications: | |||

| Calcium channel blockers, cerebral diuretics, hypertonic saline | 96.2 | ||

| Nitric oxide | 92.3 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can independently interpret findings from imaging investigations (excluding the imaging report) including: | |||

| Skeletal X-rays | 96.2 | ||

| CT – Brain | 100 | ||

| CT – Chest | 100 | ||

| CT – Spine | 100 | ||

| MRI – Brain | 100 | ||

| MRI – Spine | 96.2 | ||

| MRI – Chest | 100 | ||

| Ultrasound – Chest | 96.2 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can interpret the results from neurological equipment/examinations and functional tests including: | |||

| Electroencephalograms | 88.5 | ||

| An ability to perform a Glasgow Coma Score | 100 | ||

| An ability to perform an assessment of sedation levels | 100 | ||

| An ability to interpret an assessment of cranial nerve function | 96.2 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist understands the key principles of providing the following differing modes of mechanical/assisted ventilation including: | |||

| High frequency oscillatory ventilation | 88.5 | ||

| As a minimum standard, a physiotherapist can assess and interpret mechanical ventilation settings/measurements including: | |||

| Static and/or dynamic lung compliance measurements | 92.4 | ||

| Upper and lower inflection points of P-V curves | 92.4 | ||

| Maximum inspiratory pressure measurements | 92.4 | ||

| Maximum expiratory pressure measurements | 88.5 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can: | |||

| Assess the effectiveness/quality of a patient’s cough Record and interpret observations from physical clinical examination | 100 | ||

| Perform respiratory function tests (e.g. for measurements of FEV1, FVC, PEF) | 100 | ||

| Perform and interpret percussion note | 96.2 | ||

| Measure peak cough flow on or off mechanical ventilation | 84.6 | ||

| Measure peak inspiratory flow rate: Peak Expiratory Flow | 80.8 | ||

| Perform a spontaneous breathing trial | 96 | ||

| Interpret the rapid shallow breathing index | 80.8 | ||

| Perform a swallow assessment | 84.6 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can interpret indices from blood gas measurement including: | |||

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio | 100 | ||

| A-a gradient | 61.6* | 96 | |

| Oxygen content (CaO2) | 88.5 | ||

| Venous blood gas interpretation (including SvO2) | 69.2* | 88 | |

| A physiotherapist can complete musculoskeletal and/or functional assessments including: | |||

| Dynamometry | 88.5 | ||

| Objective measures of physical function | 100 | ||

| Perform and Interpret Chelsea Critical Care Physical Assessment Tool | 92.3 | ||

| Objective measures of cardiopulmonary exercise tolerance | 100 | ||

| Objective measures of quality of life | 84.6 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can provide the following techniques, including an understanding of indication, contraindications, evidence for technique and progressions: | |||

| Positive pressure devices for airway clearance (e.g. AstraPEP, PariPEP, TheraPEP, or oscillating expiratory pressure devices like Acapella, Flutter) | 96.2 | ||

| Periodic/intermittent CPAP (non-invasive via mask) including initiation and titration of NIV/BiPAP – for Type I or Type II respiratory failure, initiation and titration of e.g. COPD exacerbation with hypercapnia | 92.3 | ||

| NIV/BiPAP – intermittent, short term applications during physiotherapy to assist secretion mobilisation techniques or lung recruitment including initiation and titration of assisted coughing - subcostal thrusts for spinal cord injuries | 57.7* | 84 | |

| Ventilator hyperinflation via an endotracheal tube or tracheostomy | 46.2* | 92 | |

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can appropriately request/coordinate the following | |||

| Titration of inotropes to achieve physiotherapy goals | 82.6 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist is aware: | |||

| Of key literature that guides evidence-based physiotherapy practice in critical care settings | 96.2 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can accurately interpret readings from clinical monitoring including: | |||

| Central venous pressure | 100 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can accurately interpret findings from laboratory investigations including: | |||

| Renal function tests e.g. urea and creatinine | 100 | ||

| Sputum cultures | 96.2 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can | |||

| Determine the appropriateness of a patient for extubation | 82.6 | ||

| Determine the appropriateness of a patient for tracheostomy decannulation | 82.6 |

ECG = electrocardiogram; SpO2 = oxygen saturation; SvO2 = mixed venous oxygen saturation

APTT = activated partial thromboplastin time; INR = international normalised ratio; CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure

PEEP/EPAP = positive end-expiratory pressure; SIMV = synchronised intermittent mandatory ventilation; PS = pressure support

IPAP = inspiratory positive airway pressure; FiO2 = fraction of inspired oxygen; PaCO2 = partial pressure of CO2

PaO2 = partial pressure of O2; HCO3 = bicarbonate; P50 = oxygen tension at which haemoglobin is 50% saturated

CT = computed tomography; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in one second

FVC = forced vital capacity; PEF = peak expiratory flow

*Consensus not reached (>70%) after considering the scored of ‘unsure’

†Consensus not reached (>70%)

Table 3. Condition items determined as ‘essential’ (consensus >70%).

| Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 | |

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist understands pathophysiology and presenting features, likely medical management and implications for physiotherapy for a range of conditions including: | |||

| Respiratory failure types I and II | 100 | ||

| Community acquired/nosocomial/hospital-acquired pneumonia | 100 | ||

| Pleural effusion | 100 | ||

| Obstructive respiratory disease | 100 | ||

| Restrictive respiratory disease | 100 | ||

| Suppurative lung diseases | 96.2 | ||

| Acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome | 100 | ||

| Acute coronary syndrome | 96.2 | ||

| Shock (cardiogenic) | 100 | ||

| Heart failure | 100 | ||

| Post-abdominal surgery | 96.2 | ||

| Renal failure: acute and chronic | 96.2 | ||

| Immunocompromise | 92.3 | ||

| Systemic inflammatory response syndrome | 96.2 | ||

| Shock (septic) | 100 | ||

| Multi-organ failure | 100 | ||

| ICU-acquired weakness | 100 | ||

| Guillain-Barre Syndrome | 68.2* | 68 | 87.5 |

| Thromboembolic disease | 96.2 | ||

| Intracerebral haemorrhage/Subarachnoid haemorrhage | 100 | ||

| Traumatic brain injury | 100 | ||

| Chest trauma | 100 | ||

| Spinal cord injury | 96.2 | ||

| Neuromuscular disease | 96.2 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist understands pathophysiology and presenting features, likely medical management and implications for physiotherapy for a range of conditions including: | |||

| Post-cardiac surgery | 100 | ||

| Post-thoracic surgery | 100 | ||

| Pancreatitis | 88.5 | ||

| Metabolic/electrolyte disturbances | 96.2 | ||

| Fat embolism | 88.5 | ||

| Brain death and organ procurement | 76.9 | ||

| Multi-trauma | 96.2 | ||

| Sleep-disordered breathing (e.g. obstructive sleep apnoea, hypoventilation) | 88.5 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can determine the appropriateness of a patient for: | |||

| extubation | 82.6 | ||

| tracheostomy decannulation | 82.6 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist understands pathophysiology and presenting features, likely medical management and implications for physiotherapy for a range of conditions including: | |||

| Hepatitis | 69.3* | 88 | |

| Organ transplantation | 92.3 | ||

| Burns | 100 |

*Consensus not reached (>70%) after considering the scored of ‘unsure.’

Table 4. Treatment items determined as ‘essential’ (consensus >70%).

| Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 | |

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can provide the following techniques, including an understanding of indications, contraindications, evidence for the technique and progressions: | |||

| Oxygen therapy including initiation and titration of oxygen therapy | 92.3 | ||

| Humidification | 88.5 | ||

| Active cycle of breathing technique | 96.2 | ||

| Manual airway clearance techniques – percussion, vibration, chest shaking | 100 | ||

| Intermittent positive pressure breathing | 96.2 | ||

| Mechanical insufflation-exsufflation | 84.6 | ||

| Supported coughing | 92.3 | ||

| Directed coughing/instructing the patient to cough effectively | 96.2 | ||

| Assisted coughing – chest wall | 96.2 | ||

| Cough stimulation – oropharyngeal catheter stimulation | 96.2 | ||

| Manual hyperinflation via an endotracheal tube or tracheostomy | 92.3 | ||

| Nasopharyngeal airway suctioning, including insertion of NP airway | 96.2 | ||

| Oropharyngeal airway suctioning, including insertion of OP airway | 88.5 | ||

| Suction via a tracheal tube (ETT, tracheostomy, mini-tracheostomy) | 100 | ||

| Instillation of normal saline into the endotracheal tube | 88.5 | ||

| Patient positioning for respiratory care – including use of side lie, sitting upright, postural drainage (modified or head down tilt) | 100 | ||

| Patient positioning for prevention of pressure ulcers, management of tone, maintenance of musculoskeletal function | 100 | ||

| Mobilisation of non-ventilated patient | 100 | ||

| Mobilisation of ventilated patient | 96.2 | ||

| Bed exercises | 96.2 | ||

| Nasal high flow | 88.5 | ||

| Feldenkreis | 61.5† | 68 | 87.5 |

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can appropriately request/coordinate the following: | |||

| Titration of analgesia to achieve physiotherapy goals | 53.8* | 68 | 82.6 |

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist understands the key principles of providing the following differing modes of mechanical/assisted ventilation including: | |||

| Assist-control | 100 | ||

| Airway pressure release ventilation | 96.2 | ||

| Weaning protocols | 100 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can: | |||

| Interpret respiratory function tests (e.g. for measurements of FEV1, FVC, PEF) | 100 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can interpret indices from blood gas measurement including: | |||

| Lactate | 96.2 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist has knowledge of methods for advanced haemodynamic monitoring, can interpret the measurements and understands the implication of these for physiotherapists: | |||

| Implanted or external pacemakers and determine presence of pacing on ECG | 92.3 | ||

| A physiotherapist can complete musculoskeletal and/or functional assessments including: | |||

| Ability to assess tone (e.g. utilising a modified Ashworth scale) and reflexes FEV1; FVC; PEF |

96.2 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can provide the following techniques, including an understanding of indications, contraindications, evidence for the technique and progressions: | |||

| Glottal stacking (frog breathing) | 46.2* | 100 | |

| Other breathing techniques | 100 | ||

| Autogenic drainage | 88.5 | ||

| NIV/BiPAP - for use during exercise or mobilisation including initiation and titration | 60* | 84 | |

| Cough stimulation - tracheal rub | 96.2 | ||

| Recruitment maneuvers, e.g. staircase | 92.3 | ||

| Bronchial lavage | 80.8 | ||

| Assisting bronchoscopy via delivery of secretion | 88.5 | ||

| Mobilisation techniques during the procedure | 96.2 | ||

| Patient prone positioning in severe respiratory | 84.6 | ||

| Failure/acute lung injury | 96.2 | ||

| Inspiratory muscle training | 100 | ||

| Splinting and/or casting for the upper limbs and lower limbs | 100 | ||

| Collars | 92.3 | ||

| Braces | 96.2 | ||

| Treadmill, cycle ergometry or stationary bike, additional rehabilitation techniques (e.g. hydrotherapy, Wii) | 96.2 | ||

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can: | |||

| Non-invasive ventilation | 69.3* | 92 |

FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in one second

FVC = forced vital capacity

PEF = peak expiratory flow

*Consensus not reached (>70%) after considering the scored of ‘unsure’

†Consensus not reached (>70%)

Table 5. Items not reaching any consensus.

| Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 | |

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can understand equipment (including recognition of equipment), understand the implications for physiotherapy of: | |||

| Haemofiltration | 61.5* | 64 | 66.7 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump | 69.2† | 64 | 66.7 |

| Sengstaken-Blakemore/Minnesota tubes | 60† | 48 | 50 |

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can interpret indices from blood gas measurement including: | |||

| Anion gap | 50† | 60 | 62.5* |

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist has knowledge of methods for advanced haemodynamic monitoring, can interpret the measurements and understands the implication of these for physiotherapists: | |||

| Pulmonary arterial catheter measurements | 69.2† | 70.8* | 66.7* |

| PiCCO measurements | 50† | 50 | 62.5* |

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can accurately interpret findings from laboratory investigations including: | |||

| Troponin | 53.9* | 66.7 | 66.7* |

| C-reactive protein | 63.7* | 68 | 66.7 |

| Procalcitonin | 57.7* | 68 | 66.7 |

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist is aware of the actions and implications for physiotherapy of the following medications: | |||

| Prostacyclin (PG12) | 57.1* | 60 | 62.5* |

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can interpret the results from neurological equipment/examinations and functional tests including: | |||

| Ability to perform a delirium assessment | 65.4* | 52 | 58.3 |

| A physiotherapist can complete musculoskeletal and/or functional assessments including | |||

| Bioimpedence testing of body composition | 65.4* | 56 | 66.7 |

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist understands pathophysiology and presenting features, likely medical management and implications for physiotherapy for a range of conditions including: | |||

| Pancreatitis | 60* | 52 | 56.5 |

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can: | |||

| Perform a cuff volume and/or pressure test on an endotracheal tube or tracheostomy | 61.5† | 48 | 45.8 |

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can provide the following techniques, including an understanding of indications, contraindications, evidence for the technique and progressions: | |||

| Performing bronchoscopy independently | 57.7 | 44 | 58.3 |

| As a minimum standard physiotherapist can: | |||

| Intubate a patient | 57.7† | 48 | 50 |

| Extubate a patient | 65.4† | 64 | 54.2 |

| Lead the co-ordination of weaning protocols | 61.5† | 60 | 58.3 |

| Lead the co-ordination of cuff deflation trials | 48† | 48 | 45.8 |

| Lead the co-ordination of speaking valve trials | 50† | 52 | 45.8 |

| Determine the appropriateness of a patient for tracheostomy decannulation | 50† | 56 | 47.8 |

| Decannulate a tracheostomy | 50† | 44 | 54.2 |

| Tracheostomy exchange | 46.2† | 48 | 54.2 |

| As a minimum standard a physiotherapist can appropriately request/coordinate the following: | |||

| Titration of sedation to achieve physiotherapy goals | 46.1* | 64 | 66.6 |

*Consensus not reached (>70%) after considering the scored of ‘unsure’

†Consensus not reached (>70%)

Discussion

The present study aimed to assess the consensus of experienced physiotherapists working in ICUs in Nigeria with the view of determining a consensus for minimum standards of clinical practice. The present study is important in our environment because of the growing concerns about the variability of skills, level of qualifications, postgraduate experiences and clinical practice acumen of physiotherapists treating critically ill patients. Earlier studies highlighted varying standards of education, changing the on-call services, reduction in workforce capacity and irregularity in staff entry level.[19,20] We considered physiotherapists with ≥5 years of work experience in critical care settings or emergency on-call services to be experts and those with <5 years of work experience as novices based on information from previous studies.[21,22] We utilised several means including snowballing sampling technique to reach as many physiotherapists as possible to participate in the present study.

We found that 197 items of knowledge and skills were judged to be ‘essential’ as a minimum standard of clinical practice in critical care settings following three rounds of online Delphi survey. Consensus was not reached to classify any question item from the questionnaire as ‘not essential’ for clinical practice. The results of the present study are similar to those of Takahashi et al.[12] who reported consensus for 199 items from a partially modified version of the Skinner et al.[10] questionnaire. Nevertheless, our findings are different from those in Australia[10] and the UK,[11] where consensus was reached for fewer items as ‘essential’ and ‘not essential’. We think that the experts in our study had comparatively lower experience and exposure in ICUs as they were more likely to have received little or no training, and they were practicing in a resourcelimited setting. It is important to note that the scope of practice of physiotherapists in the ICU differ across countries.[21,23]

We had a good response rate, considering the low number of physiotherapists with experience in ICU clinical practice in Nigeria. Our study also recorded very low dropout rates between rounds. Twose et al.[11] reported significantly higher dropout rates in their study (from 80% in round 1 to 65% in the final round). However, this is still within the accepted range for Delphi studies.[24] It must also be stated that several reminder messages were sent to non-responders via phone calls in addition to emphasising the need to observe the deadline.[25] In addition, sending the questionnaire via WhatsApp was helpful as most participants had smartphones. Overall, the number of participants in our study was small compared with other studies, but we considered them as having the best critical care experience in view of the strict inclusion criteria.

Participants in the present study ranked more items as ‘essential’, and no items as ‘non-essential’, unlike other studies that recorded several items from the same questionnaire (Australia,[10] New Zealand,[10] Japan[12] and UK[11]). Van Aswegen et al.[26] reported consensus was achieved on knowledge of normal integrated anatomy and physiology, knowledge of and skill to conduct a holistic assessment of an ICU patient, knowledge and skill of clinical reasoning, and knowledge of physiotherapy techniques by physiotherapists working in critical care units in South Africa. Another reason for the high number of ‘essential’ question items reaching a definite consensus after the final round was because we modified the questions not reaching consensus by providing definitions and examples during the second and third rounds. Therefore, the additional consensus obtained for these items that were modified could mean that our study participants may not have been conversant with some of the question items as presented in the Skinner et al.[10] questionnaire. Specifically, most of the items not reaching consensus appear to require intensive training and high clinical skills. Therefore, it is not surprising that items on intubation/extubation of patients, interpreting measurements in ICUs such as haemofiltration, pulmonary arterial catheter measurements, C-reactive protein as well as performing cuff volume and/or pressure test on an endotracheal tube or tracheostomy, among others, did not reach consensus.

The skills and knowledge that a physiotherapist needs to deliver services independently in critical care need to be streamlined.[27] Moreover, there is lack of standardised programmes for ICU physiotherapist education in our environment.[28] In the present Delphi study, the participants appeared to agree with the majority of the items on the questionnaire, with no tangible additional items suggested across the rounds. This may be because the requirements for practice are less strict in terms of scope and responsibilities of physiotherapists in Nigeria compared with many advanced countries.[29,30] We also observed that some question items such as the Feldenkrais technique, which is not common in our critical care settings, reached consensus after the third round, after alternative definitions and examples were provided. Furthermore, items like bronchial lavage, which is a diagnostic method of the lower respiratory system in which a bronchoscope is passed into the lungs with a measured amount of fluid introduced and then collected for examination, reached consensus in the first round without necessitating alternative definitions. This technique is typically outside the physiotherapist’s scope of practice, not popular in our environment and requires high technological and technical expertise. Hence, we cannot at the moment explain why the participants must have checked ‘essential’ for this item. Nevertheless, it is important that we could still draw attention to the consensus opinion of participants of the present study using this kind of question items. Moreover, more physiotherapists working in the critical care setting are increasingly having the opportunity to acquire further knowledge and skills from online ICU rehabilitation workshops delivered by people from all parts of the world. Our study offers a good first step in approaching institutions with possible items that could form a curriculum for training of physiotherapists who will work in ICUs in Nigeria. The existing curriculum in undergraduate physiotherapy programmes in Nigeria does not provide for teaching and clinical practice experience in most of the items checked as ‘essential’. Therefore, the use of graduate physiotherapists without additional specialised training in the ICU at postgraduate level may not be desirable.

Study limitations

The instrument from Skinner et al.[10] was not locally validated prior to administration in the present study. It was noted that the questionnaire was quite detailed, with many question items covering all aspects of critical care. Nevertheless, the study results are valid because we used a consensus to arrive at the items selected eventually. Participants were given a chance in the first round of the Delphi to provide additional inputs to the question items by means of open-ended questions requiring them to suggest additional questions. However, no further suggestions were made and this may mean that they were satisfied with the instrument or they had response exhaustion due to the many questions, as observed in previous Delphi studies.[31] In the present study, the questionnaire comprised many questions and required ~30 minutes to complete. Hence, participants were given up to 2 weeks to complete the questionnaire for each round. The critical care capacity, resources and manpower are relatively low and limited in Nigeria compared with developed countries,[32] so the number of physiotherapists who were available for recruitment was relatively small. Future studies should focus on testing the knowledge of physiotherapists working in the ICU contained in the ‘essential items’ reaching consensus with a view to ascertaining specific areas of need in this environment.

Conclusion

Expert consensus was achieved for a substantial number of questions on knowledge/skills of assessment, condition and treatment. These items could be considered as ‘essential’ minimum standards of clinical practice for physiotherapists working in ICUs, based on the opinion of experienced physiotherapists in Nigeria. The results of this present study need to be further validated by appropriate authorities to support development of training programmes and curricula for critical care physiotherapy specialisation in Nigeria with a view to reducing clinical practice variability and achieving acceptable quality in patient management.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Aminudeen Abdurrahman for his invaluable insights during the revision of this manuscript. We would also like to thank the group/page handlers of the Nigeria Society of Physiotherapy and the Association of Clinical and Academic Physiotherapists in Nigeria on WhatsApp and Facebook for their help during the recruitment of the study participants.

References

- 1.Hutchings A, Durand MA, Grieve R, et al. Evaluation of modernisation of adult critical care services in England: Time series and cost effectiveness analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b4353. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masterson G, Baudouin S. 1st ed. London: Intensive Care Society; 2015. [accessed 12 September 2020]. Guidelines for the provision of intensive care services.https://www.ficm.ac.uk/sites/default/files/ Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clini E, Ambrosino N. Early physiotherapy in the respiratory intensive care unit. Respir Med. 2005;99:1096–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zafiropoulos B, Alison JA, McCarren B. Physiological responses to the early mobilisation of the intubated, ventilated abdominal surgery patient. J Physiother. 2004;50:95–100. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(14)60101-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gosselink R, Bott J, Johnson M, et al. Physiotherapy for adult patients with critical illness: Recommendations of the European Respiratory Society and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine Task Force on physiotherapy for critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:1188–1199. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castro AA, Calil SR, Freitas SA, et al. Chest physiotherapy effectiveness to reduce hospitalisation and mechanical ventilation length of stay, pulmonary infection rate and mortality in ICU patients. Respir Med. 2013;107:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Health and Medical Research Council. Canberra: NHMRC; 1999. [accessed 12 September 2020]. A guide to the development, implementation, and evaluation of clinical practice guidelines.https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0029/143696/nhmrc_clinprgde.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schultz MJ, Dunser MW, Dondorp AM, et al. Current challenges in the management of sepsis in ICUs in resource-poor settings and suggestions for the future. Intensive Care Med. 2017;1;43(5):612–612. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4750-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bott J. Is respiratory care being sidelined. Physiother Front. 2002;27 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skinner EH, Thomas P, Reeve JC, et al. Minimum standards of clinical practice for physiotherapists working in critical care settings in Australia and New Zealand: A modified Delphi technique. Physiother Theor Pr. 2016;32:468–482. doi: 10.3109/09593985.2016.1145311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Twose P, Jones U, Cornell G. Minimum standards of clinical practice for physiotherapists working in critical care settings in the United Kingdom: A modified Delphi technique. J Intensive Care Soc. 2019;20:118–131. doi: 10.1177/1751143718807019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takahashi T, Kato M, Obata K, et al. Minimum standards of clinical practice for physical therapists working in intensive care units in Japan. Phys Ther Res. 2020:E10060. doi: 10.1298/ptr.E10060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trevelyan EG, Robinson N. Delphi methodology in health research: How to do it? ;;7(4):423-428. Eur J Integr Med. 2015;7(4):423–428. doi: 10.1016/j.eujim.2015.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riviello ED, Letchford S, Achieng L, Newton MW. Critical care in resource-poor settings: Lessons learned and future directions. Critical Care Med. 2011;39(4):860–867. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0b013e318206d6d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jünger S, Payne SA, Brine J, Radbruch L, Brearley SG. Guidance on conducting and reporting Delphi studies (CREDES) in palliative care: Recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliat Med. 2017;31(8):684–706. doi: 10.1177/0269216317690685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vernon W. The Delphi technique: A review. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2009;16:69–76. doi: 10.12968/ijtr.2009.16.2.38892. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duffield C. The Delphi technique: A comparison of results obtained using two expert panels. Int J Nurs Stud. 1993;30:227–237. doi: 10.1016/0020-7489(93)90033-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delbecq AL, Van de Ven AH. A group process model for problem identification and program planning. J Appl Behav Sci. 1971;7:466–492. doi: 10.1177/002188637100700404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gough S, Doherty J. Emergency on-call duty preparation and education for newly qualified physiotherapists: A national survey. Physiother. 2007;93:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2006.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayes K, Seller D, Webb M, Hodgson C, Holland A. Ventilator hyperinflation: A survey of current physiotherapy practice in Australia and New Zealand. New Zealand J Physiother. 2011;39:124. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reeve JC. A survey of physiotherapy on-call and emergency duty services in New Zealand. New Zealand J Physiother. 2003;31(2):75–83. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berney S, Haines K, Denehy L. Physiotherapy in critical care in Australia. Cardiopulm Phys Ther J. 2012;23(1):19–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ambrosino N, Porta R. Rehabilitation, and acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lung Bio Health Dis. 2004;183:507–530. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casaburi R, Porszasz J, Burns MR, et al. Physiologic benefits of exercise training in rehabilitation of patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:1541–1551. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.5.9154855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsu C-C, Sandford BA. The Delphi technique: Making sense of consensus. Pract Assess Res Evaluation. 2007;12:10. doi: 10.7275/pdz9-th90. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edwards P, Roberts I, Clarke M, et al. Increasing response rates to postal questionnaires: Systematic review. BMJ. 2002;324:1183. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7347.1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stiller K. Physiotherapy in intensive care: An updated systematic review. Chest. 2013;144:825–847. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Aswegen H, Patman S, Plani N, et al. Developing minimum clinical standards for physiotherapy in South African ICUs: A qualitative study. J Eval Clin Pract. 2017;23:1258–1265. doi: 10.1111/jep.12774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balogun JA, Aka P, Balogun AO, et al. A phenomenological investigation of the first two decades of university-based physiotherapy education in Nigeria. Cogent Med. 2017;4:1301183. doi: 10.1080/2331205X.2017.1301183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okafor U. Challenges in critical care services in sub-Saharan Africa: Perspectives from Nigeria. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2009;13:25. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.53112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egleston BL, Miller SM, Meropol NJ. The impact of misclassification due to survey response fatigue on estimation and identifiability of treatment effects. Stat Med. 2011;30:3560–3572. doi: 10.1002/sim.4377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nwosu E, Nebo I, Kanu E, et al. Delivery of physiotherapy services in a critical care setting in Nigerian hospitals: The challenges. American Respir J Crit Care Med. 2020;201:E1635. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2020.201.1_MeetingAbstracts.A1653. [DOI] [Google Scholar]