Abstract

A blood sample from a patient who returned from Algeria with a fever inoculated on human embryonic lung fibroblasts by the shell vial cell culture technique led to the recovery of Rickettsia prowazekii. The last clinical strain was isolated 30 years ago. Shell vial cell culture is a versatile method that could replace the classic animal and/or embryonated egg inoculation.

Epidemic typhus is a body louse-transmitted disease due to Rickettsia prowazekii. Recent reports of cases occurring in Burundi (12), in Russia (16), and in Peru (unpublished data) and the present case from a patient returning from Algeria must remind us that epidemic typhus is a reemerging disease. The laboratory diagnosis of epidemic typhus is based on serology but is hampered by cross-reaction with murine typhus (7). The shell vial assay (8), originally devised for the isolation of viruses, has now been adapted by members of our team for the isolation of spotted fever group rickettsiae (7). In this report, we describe the first application of this method to the isolation of R. prowazekii.

Case report.

A 65-year-old man was referred to our hospital center in October 1998 for fever and diarrhea. This native Algerian, who usually lives in France, returned to France by boat after a visit to Algeria. On arrival in Marseille, he suffered fever, vomiting, myalgias, and diarrhea. On examination he presented with a high fever of 40.6°C and a dissociated pulse. The patient exhibited mild confusion. A discrete rash and splenomegaly were noticed. A presumptive diagnosis of typhoid fever was made, and treatment with ceftriaxone (3 g/day, administered intravenously) was started immediately. By day three, blood and stool cultures were negative and the patient's condition had worsened. He was still febrile, dyspnea was noted, the rash became purpuric, and the patient was semicomatose. A diagnosis of typhus (murine or epidemic) was suspected and doxycycline (200 mg/day) was prescribed. His condition rapidly improved, as he was afebrile within 3 days.

A blood sample from the patient was inoculated onto three shell vials containing human embryonic lung (HEL) fibroblasts grown on coverslips, as previously described (6), in a biosafety level 3 containment laboratory. Detection of growing bacteria was carried out by cytocentrifugation of 100 μl of one shell vial supernatant for further Gimenez staining and directly inside the shell vial by immunofluorescence. After fixation with cold acetone, the vial was washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). One hundred microliters of the patient's convalescent serum (taken 1 week after admission), diluted 1:50 in PBS with 3% nonfat dry milk, was added, and the vial was incubated at 37°C with 100 μl of a fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-human immunoglobulin (Ig) (Fluoline H; Biomerieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) diluted 1:200 in PBS containing 0.2% Evans blue. After three washes with PBS, the coverslip was mounted (cells face down) in phosphate-buffered glycerol medium (pH 8) and examined at 400× with a Zeiss epifluorescence microscope. This detection procedure was performed on days 7 and 14. The supernatant of a positive shell vial was used for PCR-based identification and was inoculated on confluent layers of HEL cells in a 150-cm2 culture flask in order to establish the isolate.

DNA extracts suitable for use as the template in PCR assays were prepared from one remaining shell vial. These DNA extracts were amplified by using PCR incorporating primers that allow amplification of genes encoding the citrate synthase (gltA) and the rickettsial outer membrane protein rOmpB (ompB). Sequencing reactions were carried out by incorporating the same primers as those used for amplification, and sequence products were resolved in the ABI PRISM 377 automatic sequencing system (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom).

As this patient came from an area not known as a region of endemicity for epidemic typhus, determination of antibody to R. typhi was initially performed by indirect fluorescent-antibody assay, as previously described (12), on sera taken on admission and 1 week later. Antibodies to R. prowazekii were further determined.

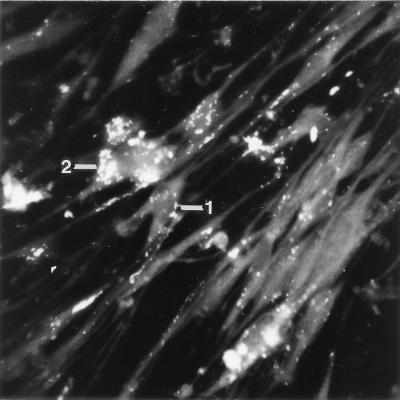

Gimenez staining performed on day 7 was negative. Gimenez staining performed on day 14 yielded numerous red-stained bacteria located in the cytoplasm of HEL cells. The coverslip of the same shell vial allowed detection of numerous fluorescent bacteria in intracellular locations (Fig. 1). The supernatants of positive shell vials inoculated on confluent layers of HEL cells allowed establishment of the isolate. The nucleotidic sequence obtained was compared to all previously reported sequences of these genes by a Gapped Blast 2.0 (National Center for Biotechnology Information) search of the GenBank database. The sequences derived from the shell vial isolate were found to share 100% sequence similarity with those of R. prowazekii already deposited in GenBank. By indirect fluorescent-antibody assay seroconversion to R. typhi was first demonstrated (in convalescent serum, an IgG titer of 1:2,048 and an IgM titer of 1:128 were determined). In convalescent serum, an IgG antibody titer of 1:4,096 and an IgM antibody titer of 1:128 against R. prowazekii were determined.

FIG. 1.

Immunofluorescence staining of R. prowazekii within HEL cells on a coverslip from a shell vial inoculated with a blood sample from the patient. Magnification, ×400. Bacteria are isolated (label 1) or grouped in clusters (label 2).

The clinical isolation of R. prowazekii, based on inoculation of clinical samples on animals, has not been reported for 30 years (3). The last reported isolates of R. prowazekii were isolated 20 years ago from flying squirrels by using embryonated hen's eggs (1). Adult male guinea pigs have long been the animal of choice for primary isolation of R. prowazekii, but isolation can be obtained with mice. The use of animals, especially guinea pigs, for diagnosis is not convenient for most laboratories because it requires that animals be easily available and specific equipment be kept. As bacteria are shed by animals, contamination of laboratory workers or other experimental animals can occur, so the animals must be kept in specially designed cages equipped with filters. Given the ever-lessening tendency to use animals for research or diagnosis, efforts must be made to replace them whenever possible (13). Culture on embryonated chicken egg yolk sacs has also been widely used (2). This procedure requires embryonated eggs of 5 to 8 days of age from flocks fed an antibiotic-free diet, which are often difficult to obtain rapidly without subscribing to the services of an animal supplier and often need several blind passages to obtain an isolate. Furthermore, they are easily contaminated. The cell culture procedure described more than 60 years ago is now the most widely used method for isolating rickettsiae from clinical samples (10). The centrifugation-shell vial system (8) is a versatile and rapid method which can be applied to many viruses as well as facultative or strictly intracellular bacteria. We have used this technique routinely and successfully to isolate spotted fever rickettsiae (6), Coxiella burnetii (9), Bartonella sp. (11), Francisella tularensis (4), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (unpublished data), and Legionella pneumophila (5) from blood and tissue biopsies. To avoid bacterial contamination, antibiotics with no activity against rickettsiae, such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or vancomycin, may be added. The small surface area of the coverslip containing cells enhances the ratio of the number of rickettsiae to the number of cells and allows more efficient recovery. When used with HEL cells (which have the advantage that once a monolayer is established, contact inhibition prevents further division), as was done for this report, incubation may be prolonged. Furthermore, by comparison to conventional cell culture procedures, the centrifugation step after inoculation enhances rickettsial attachment to and penetration of cells (18). After inoculation and incubation in shell vials, detection of bacteria can be assessed by the use of acridine orange, Gimenez, and Giemsa stainings of the shell vial supernatant or by immunofluorescence staining of the cell monolayer by using the patient serum, if suitable, or sera from immune animals as the primary antibody. When bacterial growth is detected, identification can be achieved by PCR amplification and then sequencing of universal genes such as the 16S rRNA gene or of specific genes, such as gltA, ompB or ompA, for rickettsiae (14, 15). PCR assay performed on blood has been proposed as an efficient technique to detect rickettsiae, but in our experience and that of others it has proven less sensitive than the shell vial assay (6, 17).

As the use of the shell vial technique for isolation of rickettsiae is restricted to specialized research and public health laboratories that have biosafety level 3 containment, it is not suitable for use in most clinical microbiology laboratories, especially in poor countries where epidemic typhus is more likely to reemerge. However, in its favor, this procedure provides a means for the isolation of a wide range of intracellular bacteria that are usually isolated by inoculation of animals, and so may help save animals, and is well adapted to isolation of such bacteria in developed countries for travelers returning from areas of endemicity. Furthermore, as shown in this case, it allows determination of the infecting bacterial species, whereas sera cross-react extensively with closely related species.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bozeman F M, Masiello S A, Williams M S, Elisberg B L. Epidemic typhus rickettsiae isolated from flying squirrels. Nature. 1975;255:545–547. doi: 10.1038/255545a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cox H R. Use of yolk sac of developing chick embryo as medium for growing rickettsiae of Rocky Mountain spotted fever and typhus group. Public Health Rep. 1938;53:2241–2247. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eremeeva M E, Ignatovich V F, Dasch G A, Raoult D, Balayeva N M. Genetic, biological and serological differentiation of Rickettsia prowazekii and Rickettsia typhi. In: Kazar J, Toman R, editors. Rickettsia and rickettsial diseases. Bratislava, Slovakia: Veda; 1996. pp. 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fournier P E, Bernabeu L, Schubert B, Mutillod M, Roux V, Raoult D. Isolation of Francisella tularensis by centrifugation of shell vial cell culture from an inoculation eschar. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2782–2783. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2782-2783.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.La Scola B, Michel G, Raoult D. Isolation of Legionella pneumophila by centrifugation of shell vial cell cultures from multiple liver and lung abscesses. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:785–787. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.3.785-787.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.La Scola B, Raoult D. Diagnosis of Mediterranean spotted fever by cultivation of Rickettsia conorii from blood and skin samples using the centrifugation-shell vial technique and by detection of R. conorii in circulating endothelial cells: a 6-year follow-up. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2722–2727. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.11.2722-2727.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.La Scola B, Raoult D. Laboratory diagnosis of rickettsioses: current approaches to diagnosis of old and new rickettsial diseases. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2715–2727. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.11.2715-2727.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marrero M, Raoult D. Centrifugation-shell vial technique for rapid detection of Mediterranean spotted fever rickettsia in blood culture. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989;40:197–199. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1989.40.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Musso D, Raoult D. Coxiella burnetii blood cultures from acute and chronic Q-fever patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3129–3132. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.12.3129-3132.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nigg C, Landsteiner K. Studies on the cultivation of the typhus fever rickettsia in the presence of live tissue. J Exp Med. 1932;55:563–576. doi: 10.1084/jem.55.4.563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raoult D, Fournier P E, Drancourt M, Marrie T J, Etienne J, Cosserat J, Cacoub P, Poinsignon Y, Leclercq P, Sefton A. Diagnosis of 22 new cases of Bartonella endocarditis. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:646–652. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-8-199610150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raoult D, Ndihokubwayo J B, Tissot-Dupont H, Roux V, Faugere B, Abegbinni R, Birtles R J. Outbreak of epidemic typhus associated with trench fever in Burundi. Lancet. 1998;352:353–358. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)12433-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roush W. Hunting for animal alternatives. Science. 1996;274:168–171. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5285.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roux V, Fournier P E, Raoult D. Differentiation of spotted fever group rickettsiae by sequencing and analysis of restriction fragment length polymorphism of PCR-amplified DNA of the gene encoding the protein rOmpA. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2058–2065. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2058-2065.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roux V, Rydkina E, Eremeeva M, Raoult D. Citrate synthase gene comparison, a new tool for phylogenetic analysis, and its application for the rickettsiae. Int J Syst Bact. 1997;47:252–261. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-2-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tarasevich I, Rydkina E, Raoult D. Epidemic typhus in Russia. Lancet. 1998;352:1151. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)79799-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tzianabos T, Anderson B E, McDade J E. Detection of Rickettsia rickettsii DNA in clinical specimens by using polymerase chain reaction technology. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:2866–2868. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.12.2866-2868.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiss E, Dressler H R. Centrifugation of rickettsiae and viruses onto cells and its effect on infection. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1960;103:691–695. doi: 10.3181/00379727-103-25637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]