Abstract

To assess pneumococcal strain variability among young asymptomatic carriers in Chile, we used serotyping, antibiotic susceptibility testing, and genotyping to analyze 68 multidrug-resistant pneumococcal isolates recovered from 54 asymptomatic children 6 to 48 months of age. The isolates represented capsular serotypes 19F (43 isolates), 14 (14 isolates), 23F (7 isolates), 6B (3 isolates), and 6A (1 isolate). Genotypic analysis, which included pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) of chromosomal digests, penicillin binding protein (PBP) gene fingerprinting, and dhf gene fingerprinting, revealed that the isolates represented six different genetic lineages. Clear circumstantial evidence of capsular switching was seen within each of four of the genetically related sets. The majority of the isolates, consisting of the 43 19F isolates and 2 type 6B isolates, appeared to represent a genetically highly related set distinct from previously characterized pneumococcal strains. Each of three other genetically defined lineages was closely related to one of the previously characterized clones Spain6B-2, France9V-3, or Spain23F-1. A fifth lineage was comprised of four type 23F isolates that, by the techniques used for this study, were genetically indistinguishable from three recent type 19F sterile-site isolates from the United States. Finally, a sixth lineage was represented by a single type 23F isolate which had a unique PFGE type and unique PBP and dhf gene fingerprints.

Pneumococci resistant to β-lactam antibiotics have originated through recombination events between penicillin binding protein (PBP) genes of pneumococci and closely related species, and resistant pneumococcal PBP gene alleles have also frequently arisen through intraspecies recombination events (4, 5, 11, 21, 22, 29, 30, 33). Resistant pneumococci with resultant mosaic PBP genes are not at a selective disadvantage in the absence of β-lactam antibiotic selection, and specific clones have been widely disseminated worldwide (5, 30). The percentages of the main pneumococcal serotypes causing infections vary in different locations of the world, but for unknown reasons, β-lactam resistance worldwide is usually associated with a minority of serotypes that commonly cause infections, including 19F, 23F, 14, 9V, 9A, 6B, and 6A (4–6, 9, 14, 23, 25, 29, 30, 31, 33).

Another major contribution to the strain diversity of β-lactam-resistant pneumococci is the well-documented phenomenon of capsular switching due to intraspecies recombination events at the cps locus (2, 4, 7, 8, 18, 27). Capsular switching is a medical concern because of the possibility that antibiotic-resistant strains may switch to capsular types not included in the vaccine in use and because of potentially increased virulence attributed to capsular type switching (18, 27).

Young children are often asymptomatic carriers of pneumococcal strains of widely varying serotypes; however, these children develop acute otitis media more frequently than do noncarriers (13). It was of interest in this study to determine the serotype distribution and genetic variability among penicillin-resistant nasopharyngeal isolates from asymptomatic children, since such findings could impact otitis media treatment and vaccine formulation strategies. Previous reports have confirmed that a large percentage of worldwide pneumococcal β-lactam resistance is due to the spread of specific clones to widely separated countries. The work shown here indicates that while a significant number of pneumococcal nasopharyngeal isolates from young children in Chile appear closely related to previously characterized isolates from widely separated geographic areas, the majority of the isolates in this study appear to represent a newly discovered lineage.

Bacterial isolates.

Isolates were recovered from asymptomatic children between the ages of 6 and 48 months attending 10 different day care centers in Santiago, Chile, 1994 to 1999. Nasopharyngeal (NP) cultures were obtained on days 1, 56, and 112 from each of 204 to 228 children, for a total of 472 NP cultures. On days 56 and 112, cultures were obtained from only 204 of the 228 children. The total number of pneumococcus-positive cultures was 472 from days 1 (139 of 228 children), 56 (174 of 204), and 112 (159 of 204). Of these 472 pneumococcal cultures, 233 were found to have intermediate penicillin resistance and 77 were resistant. Since a single resistant NP isolate obtained from a day care center in Temuco, Chile, was the only penicillin-resistant isolate reported from an ongoing study in this location (17), it was also included. Sixty-eight of the 78 resistant cultures obtained from a total of 54 asymptomatic children were available for the genotypic analysis done in this study. When these isolates were tested again for penicillin susceptibility at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Streptococcus laboratory, 53 of the cultures were found to be penicillin resistant (MIC, ≥2 μg/ml) while an intermediate penicillin resistance MIC of 1 μg/ml was found for the other 15.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing.

MICs of antibiotic for the 68 cultures were determined at the CDC Streptococcus laboratory by the Pasco MIC/ID broth microdilution system (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.).

Previously characterized clones.

The following previously genetically characterized strains were provided by L. McDougal and F. Tenover (Antimicrobial Investigations Laboratory, CDC) and designated according to the Pneumococcal Molecular Epidemiology Network (19, 24). These included clones Spain23F-1 (strain SP264 [ATCC 700669]) (4, 25), Spain6B-2 (ATCC 700670) (26), France9V-3 (strain SP195, which is highly related to strain 665 [ATCC 700671]) (4, 29), Tennessee23F-4 (strain SP196 [ATCC 51916]) (23, 29), England14-9 (strain SP200 [ATCC 700676]) (16), Spain14-5 (strain VH14 [ATCC 700672]) (6), Hungary19A-6 (ATCC 700673) (25), S. Africa19A-7 (strain 17619 [ATCC 700674]) (31), S. Africa6B-8 (strain Sp199 [ATCC 700675]) (31), Slovakia14-10 (strain 91-006571 [ATCC 700677]) (14), and Slovakia19A-11 (strain 91-0006571 [ATCC 700678]) (14). Strains Mn14, Or19F, Ga23F, and Ca6B represent isolates obtained during a recent study of 1997 U.S. sterile-site isolates (15).

PCR and restriction analysis.

Primers were selected based on published sequences of pbp1A (22), pbp2B (10), pbp2X (20), and dhf (1, 28). Primers pbp2bf (GATCCTCTAAATGATTCTCAGGTGGCTGT) and pbp2br (GTCAATTAGCTTAGCAATAGGTGTTGGAT) were used to amplify the pbp2B gene. Primers pn1af (GGCATTCGATTTGATTCGCTTCTATCAT) and pn1ar (CTGAGAAGATGTCTTCTCAGGCTTTTG) were used to amplify pbp1A. Primers pbp2xf (CGTGGGACTATTTATGACCGAAATGGAG) and pbp2xr2 (GGCGAATTCCAGCACTGATGGAAATAA) were used to amplify pbp2X. Primers dfrf (CTATTTTGTAAGCTATTCCAAACCAGTCT) and dfrr (GCTCCTGCCAGAAGGCAGATGAAACACAG) were used to amplify dhf.

PBP gene amplicons were subjected to HaeIII and RsaI digestion by the addition of 3 U each of the respective enzymes to 10 μl of unpurified PCR product, followed by 0.5 h or more of incubation at 37°C. dhf amplicons were subjected to HaeIII, RsaI, and Hinf1 digestion in the same manner with the addition of 3 U of each enzyme. Digests were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis as previously described (3).

PFGE.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) of chromosomal SmaI digests was carried out as previously described (12). Isolates differing from subtype 1 of each group (type) by only one to six bands were assigned to the same type. Isolates within these types with exactly the same PFGE profile were assigned to the same subtype. Isolates with more than six bands of difference from subtype 1 of each type were considered unrelated isolates (32) and assigned to a different PFGE type.

Findings.

Five different capsular serotypes commonly associated with penicillin resistance worldwide were found among the 68 isolates of this study. In a recent study, 22 different pneumococcal serotypes were found among nasopharyngeal isolates from Santiago (17). Antibiotic resistance was identified among isolates of five serotypes, and these five serotypes were the same as those found in this study (17).

As shown in Table 1, all 68 isolates were subjected to molecular genotyping by analysis of PBP gene and dhf (dihydrofolate reductase gene) restriction enzyme fingerprinting and by PFGE analysis of genomic digests. With the exception of two PFGE types, all of the PFGE types represented more than one isolate taken from two or more asymptomatic carriers in Santiago, Chile. A single isolate with a unique PFGE type (type W [see Fig. 2]) was recovered from one individual from Temuco, Chile. Additionally, a single PFGE type K (see Fig. 2, discussed below) was found. Of the six PFGE types found during this study (Table 1; Fig. 1), we had encountered four in a recent study of β-lactam-resistant U.S. sterile-site isolates recovered in 1997 (represented by strains Mn14, Or19F, Ga23F, and Ca6B in Table 1) (15). However, the majority (45 of 68) of these recent isolates from Chile displayed the new PFGE type, type V (Table 1; Fig. 1, lanes 2 and 3), and were recovered from 36 of the 54 children harboring β-lactam-resistant pneumococci.

TABLE 1.

Genetically related groups of pneumococci from Chilea

| Clone (reference[s]) or no. of isolatesb | MIC (μg/ml)

|

RFLP profile

|

PFGE type | Serotype | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEN | CEF | TMP | ERY | CHL | CLIN | pbp1A | pbp2B | pbp2X | dhf | |||

| 24c | 2–4 | 0.5 | ≥4 | ≤0.12 | <2 | ≤0.25 | 13 | 14 | 25 | 2 | V1 | 19F |

| 10 | 2–4 | 1 | ≥4 | ≤0.12 | <2 | ≤0.25 | 13 | 14 | 25 | 2 | V1 | 19F |

| 1 | 4 | 1 | >8 | >16 | <2 | 0.12 | 13 | 14 | 25 | 2 | V1 | 19F |

| 1 | 4 | 1 | >8 | >16 | <2 | >2 | 13 | 14 | 25 | 2 | V1 | 19F |

| 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | >8 | 0.12 | <2 | 0.12 | 13 | 14 | 25 | 1 | V1 | 6B |

| 1 | 2 | 0.5 | >8 | <0.06 | <2 | <0.06 | 13 | 14 | 25 | 1 | V1 | 6B |

| 1 | 2 | 0.5 | >8 | 0.12 | <2 | 0.12 | 13 | 14 | 25 | 1 | V1 | 19F |

| 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 4 | <0.06 | <2 | <0.06 | 13 | 14 | 2 | 1 | V1 | 19F |

| 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 4 | <0.06 | <2 | 0.12 | 14 | 14 | 25 | 1 | V1 | 19F |

| 1 | 2 | 0.5 | >8 | <0.06 | <2 | 0.12 | 14 | 14 | 25 | 2 | V1 | 19F |

| 3d | 2 | 0.5 | >8 | 0.12 | <2 | 0.12 | 13 | 25 | 2 | 1 | V2 | 19F |

| Fr9V-3 (4, 29) | 2 | 1 | >8 | 0.12 | <2 | 0.12 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 | B1 | 9V |

| Mn14 (15) | 2 | 2 | >8 | 0.12 | <2 | 0.12 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 | B2 | 14 |

| 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | <0.06 | <2 | <0.06 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 | B2 | 14 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | <0.06 | <2 | 0.12 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 2 | B23 | 14 |

| 4 | 1 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.12 | <2 | 0.12 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 2 | B23 | 14 |

| 3e | 1 | 0.5 | 2 | <0.06 | <2 | 0.12 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 | B24 | 14 |

| 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 4 | <0.06 | <2 | 0.12 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 2 | B24 | 14 |

| 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 4 | <0.06 | <2 | 0.12 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 2 | B24 | 14 |

| 2 | 1 | 0.25 | 4 | <0.06 | <2 | 0.12 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 | B24 | 14 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0.12 | <2 | 0.12 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 2 | B25 | 14 |

| Or19f (15) | 4 | 1 | >8 | 8 | <2 | >2 | 12 | 3 | 4 | 2 | G1 | 19F |

| 1f | 2 | 0.5 | >8 | >16 | <2 | >2 | 12 | 3 | 25 | 2 | G1 | 23F |

| 3 | 2 | 1 | >8 | >16 | <2 | >2 | 12 | 3 | 25 | 2 | G1 | 23F |

| Sp23f (4, 25) | 2 | 0.5 | 4 | <0.06 | >16 | <0.06 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 | A1 | 23F |

| Ga23f (15) | 2 | 2 | >8 | >16 | >16 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 | A2 | 23F |

| 1g | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0.12 | >16 | >0.06 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 | A1 | 23F |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0.12 | >16 | 0.12 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 | A1 | 23F |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0.12 | >16 | 0.12 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 | A7 | 6A |

| Sp6B-2 (26) | 2 | 1 | 4 | >16 | >16 | >2 | 8 | 22 | 12 | 5 | K1 | 6B |

| Ca6B (15) | 4 | 1 | 8 | >16 | >16 | >2 | 8 | 22 | 12 | 9 | K3 | 6B |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | >16 | >16 | >2 | 8 | 22 | 12 | 9 | K6 | 6B |

| 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 0.12 | <2 | 0.12 | 13 | 26 | 25 | 2 | W1 | 23F |

Abbreviations: PEN, penicillin; CEF, cefotaxime; TMP, trimethoprim; ERY, erythromycin; CHL, chloramphenicol; CLIN, clindamycin; Sp, Spain; Fr, France; Mn, Minnesota; K, Korea; Ga, Georgia; Or, Oregon; Ca, California.

The following refer to representative isolates from a genotypic survey of β-lactam-resistant pneumococcal isolates recovered in the United States in 1997: Mn14, 1 of 17 PFGE subtype B2 isolates; Or19F, 1 of 2 PFGE subtype G1 isolates; Ga19F, 1 of 18 PFGE subtype A2 isolates; Md6B, a single PFGE subtype K2 isolate.

The 42 PFGE subtype V1 isolates were recovered from only 34 children, since 2 or 3 type V1 isolates were recovered from each of 6 children.

Two of the three PFGE subtype V2 isolates were recovered from the same child.

Two of the seven PFGE subtype B24 isolates were recovered from the same child.

Two of the four PFGE subtype G1 isolates were recovered from the same child.

Both PFGE subtype A1 isolates were recovered from the same child.

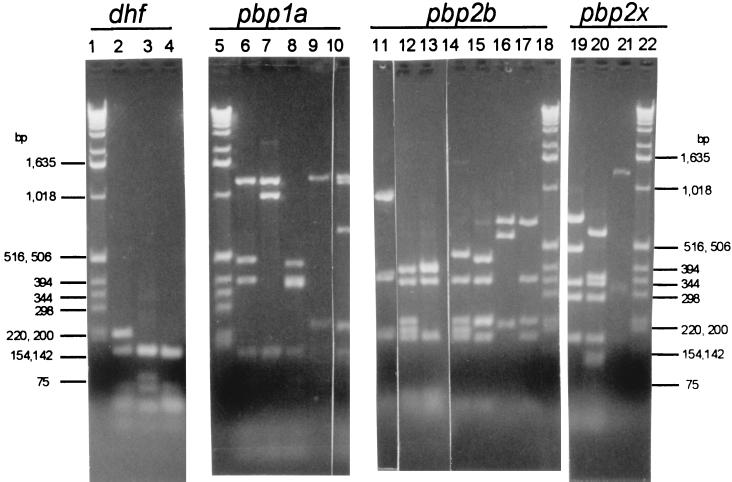

FIG. 2.

RFLP profiles for dhf, pbp1A, pbp2B, and pbp2X encountered among 68 NP isolates from children in Chile. Lanes: 2 to 4, dhf profiles 2, 1, and 9, respectively; 6 to 10, pbp1A profiles 8, 6, 12, 13, and 14, respectively; 11 to 17, pbp2B profiles 5, 3, 6, 14, 25, 22, and 26, respectively; 19 to 21, pbp2X profiles 2, 25, and 12, respectively.

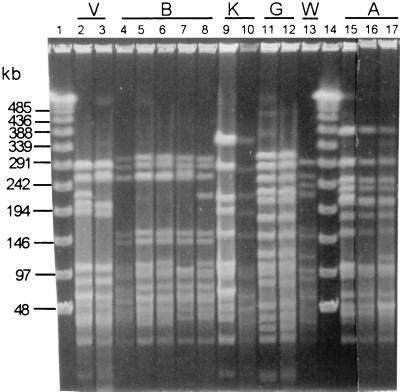

FIG. 1.

PFGE types A, B, G, K, and V encountered among the 68 NP isolates from children in Chile. Lanes: 2 and 3, PFGE subtypes V1 and V2 from Chile isolates; 4 to 8, PFGE subtypes B1 (from France9V-1), B2 (from a 1997 U.S. project [15]), B2 (Chilean isolate), B23 (Chilean isolate), and B24 (Chilean isolate) (note that subtype B25 is not shown but differs from subtype B1 by only four bands); 9 and 10, PFGE subtypes K1 and K6 from Spain6B-1 and a Chilean isolate, respectively; 11 and 12, subtype G1 from the 1997 U.S. study (15) and a Chilean isolate, respectively; 13, unique PFGE subtype W1; 15 and 16, PFGE subtype A1 from Spain23F-1 and a Chilean isolate, respectively; 17, PFGE subtype A7 from a Chilean isolate. Lanes 1 and 14 contain molecular size markers.

Through PBP gene fingerprinting and sequence analysis, it has been shown that there is much heterogeneity within the pbp1A, pbp2B, and pbp2X genes of β-lactam-resistant pneumococcal clinical isolates, while these genes are very conserved among β-lactam-sensitive isolates. In our recent study of 241 U.S. clinical isolates (15), by using the protocol used for this work, we found 13, 24, and 24 fingerprint profiles for pbp1A, pbp2B, and pbp2X, respectively. The RFLP profile numbers between 1-13, 1-24, and 1-24 in Table 1 represent these previously found RFLP profiles for pbp1A, pbp2B, and pbp2X, respectively. Profiles pbp1A-13, pbp2B-25, pbp2B-26, and pbp2X-25 represent RFLP profiles we did not encounter in our U.S. survey. Consistent with other studies (4, 10, 11, 20, 21, 29, 30), we have found very little profile variation in the PBP genes among the majority of β-lactam-sensitive isolates (3, 15).

Similarly, consistent with previous findings (1, 28), we found a high degree of sequence and RFLP profile heterogeneity of the dhf gene among trimethoprim-resistant pneumococcal isolates and very little variation among trimethoprim-sensitive isolates (15). Although dhf profile 1 was the most frequent profile found in sensitive U.S. isolates, we also found dhf profile 1 in a small number of resistant isolates. Nucleotide sequences of RFLP profile 1 resistant dhf alleles indicated that some of these alleles contained extensive nucleotide changes characteristic of mosaic genes arising from recombination events with closely related species (1, 15), while other profile 1 resistant alleles contained only one to three characteristic point mutations (15, 28). Of the 15 different dhf profiles seen in trimethoprim-resistant and intermediately resistant isolates from our U.S. study, only 3 (profiles 1, 2, and 9) (Fig. 2, lanes 2 to 4) were seen in the isolates of this study, and all but three intermediately resistant isolates of this study were fully trimethoprim resistant (Table 1). The data presented here is consistent with the most frequent correlation of dhf profile 1 (dhf-1) with trimethoprim sensitivity; however, five of the six dhf-1 isolates from this study were fully trimethoprim resistant. Two of the PFGE type V2 dhf-1 isolates were from the same child.

Consistent with the probability of very high genomic relatedness predicted by isolates with similar PFGE patterns, each of the four multi-isolate PFGE type isolates was characterized by closely matching restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) profiles of the four target gene amplicons (Table 1). The majority of the isolates (45 of 68) were of PFGE type V (Table 1), with 42 of these isolates displaying PFGE subtype V1 and the other 3 isolates showing the very similar subtype V2 (Fig. 1, lanes 2 and 3). Except for two type 6B isolates, all of these PFGE type V isolates were of serotype 19F. All of these isolates had very similar pbp1A-pbp2B-pbp2X-dhf composite RFLP profiles (Table 1). It is possible that the PFGE type V isolates represent a local resistant clone that has not yet undergone extensive geographic spread. The closely matching genotypes (consisting of four RFLP profiles and the PFGE V1 subtype shown in Table 1) of the type 19F isolates and the two type 6B isolates suggest that the latter possibly arose through a horizontal recombination event with a PFGE subtype V1, serotype 19F recipient of a serotype 6B DNA fragment containing type-specific cps genes. This association between serotypes 19F and 6B is consistent with recent observations (8).

Subtype B1 was found in the previously characterized France9V-3 clone (4). We found 14 isolates in this study (from 13 children) with one of four PFGE subtypes very similar to subtype B1 (Table 1) (Fig. 1, lanes 4 to 8). We found that 40 isolates of a geographically diverse set of 141 β-lactam-resistant isolates (28%) recovered from U.S. patients in 1997 were of PFGE type B (representing 17 type B subtypes), and roughly one-third of them were of serotype 14 (15). Additionally, the composite RFLP profile shown in Table 1 closely matches those found in the U.S. isolates, where the predominant pattern for the four amplicons was also 6/6/2/2 (Table 1). It is notable that subtype B2, found in a single serotype 14 isolate in this study (Table 1; Fig. 1, lanes 5 and 6), was the most common type B subtype found in the U.S. study, accounting for 17 of the 40 type B isolates from six different states and representing serotypes 9V, 14, and 9A (15).

We found that four serotype 23F isolates (from three children) had the same PFGE subtype (PFGE type G1 in Table 1; Fig. 2, lanes 11 and 12) and amplicon RFLP profiles nearly identical to those of recent U.S. serotype 19F isolates from three different states (represented by Or19F in Table 1) (15). These results indicate that subtype G1 isolates are geographically broadly dispersed and that a capsular switching event has occurred within this genetic background, leading to a possibly predominantly serotype 23F population of PFGE subtype G1 pneumococci in Santiago, Chile.

It is significant that three RFLP profiles were found among these isolates that we had not previously encountered in our recent survey of U.S. isolates recovered in 1997. pbp1A profile 14 (1a-14) and pbp2B profile 25 (2b-25) were found among two and three PFGE type V1 isolates, respectively (Table 1; Fig. 2, lanes 10 and 16, respectively). It is interesting that the new profile 2x-25 (Fig. 2, lane 20) was the major pbp2X profile found among the PFGE subtype V1 isolates and was also found among the subtype G1 isolates. The genotype found among the subtype G1 isolates was nearly identical to that of isolates from Oregon (Table 1), with the exception of 2x-25. It would be interesting to compare the sequences of the 2x-25 alleles and the 2x-4 allele represented by the Or19F isolate. By comparing the mosaic patterns and/or base substitutions within these alleles, it may be possible to determine if one allele is likely to have directly arisen through alteration of the other. Although in this instance, the relative contributions of these pbp2X alleles to β-lactam resistance are not clear (the Or19F isolate and three of the four subtype G1 Chilean isolates are penicillin resistant and cefotaxime intermediate), in other situations comparing PBP gene alleles between closely related strains could provide clues for the origins of increased β-lactam resistance.

Three isolates from Santiago were found to be closely related to the well-documented internationally disseminated clone Spain23F-1 (4, 25), and two of these three isolates had the same PFGE subtype, A1, as Spain23F-1 (Table 1; Fig. 1, lanes 15 and 16). In our 1997 U.S. study described above, 23 (16%) of 141 population-based β-lactam-resistant isolates were of PFGE type A and 21 of these 23 isolates had the composite PBP gene-dhf profile 6/6/2/2 also shown by the three PFGE type A isolates from Santiago (Table 1) (15).

A single isolate (subtype K6) was found that had a PFGE type closely matching that of the previously described clone Spain6B-2 (26) (Fig. 1, lanes 9 and 10) and one of four isolates from our 1997 U.S. population-based survey (designated Ca6B in Table 1). The composite RFLP profile (8/22/12/9) shared by the single Chilean subtype K6 isolate and the U.S. subtype K3 isolate MD6B also undoubtedly indicates very close genetic relatedness (Table 1).

Finally, a new PFGE type (W1; Fig. 1, lane 13) was found in a single hospital isolate from Temuco, Chile. This isolate displayed unique RFLP pattern 26 for pbp2B and shared previously undescribed pbp2X profile 25 with the majority of the subtype V1 isolates and a single subtype G1 isolate (Table 1). This latter observation may be indicative of recombination events occurring between unrelated isolates in this general geographic area, since pbp2X profile 25 was quite common in the Santiago isolates and was not found in our recent U.S. survey (15).

It is evident that the majority of isolates were cefotaxime sensitive by National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards guideline values (Table 1). However, although not shown in Table 1, the cefotaxime MIC for all but three of these sensitive isolates was actually 0.5 μg/ml and for none of them was the MIC lower than 0.25 μg/ml. In our experience, for wild-type pneumococcal isolates with unaltered PBP genes, the cefotaxime MICs are 0.03 to 0.06 μg/ml, while isolates for which the MICs are 0.25 μg/ml or higher generally have mosaic PBP genes (15).

Features of the antibiotic susceptibility profiles conserved between the genetically related, geographically separate PFGE types were apparent. Except for two type V1 isolates, all of the 61 PFGE type V and B isolates (including France9V-3) were uniformly erythromycin, chloramphenicol, and clindamycin sensitive. All five type G isolates (including Or19F) were erythromycin resistant, and four of the five (including Or19F) were clindamycin resistant. All 8 type A and type K isolates, including Spain23F-1, GA23F, Spain6B-2, Ca6B, and the 4 Chile isolates, were uniformly chloramphenicol resistant, in contrast to the other 64 NP study isolates.

To recapitulate, among 68 clinical isolates from Chile, we identified six distinct genetically related populations by genomic PFGE analysis (Table 1; Fig. 1). Among the six PFGE types, we found 16 different composite RFLP types for the pbp1A, pbp2B, pbp2X, and dhf gene amplicons (Table 1; Fig. 2). Four of these six PFGE types were shared by previously described widely distributed clones and isolates of our recent study of 141 β-lactam-resistant isolates from the United States recovered in 1997 (15), although the majority of the isolates in this study apparently represent a newly described pneumococcal strain.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to L. McDougal and F. Tenover for generously providing genetically characterized strains. We thank A. R. Franklin, A. Hurz, and D. Jackson for serotyping and susceptibility testing.

Work performed in Chile by J.S.I., M.O., V.P., S.P., and C.A. was supported in part by a grant from Ross Products Division, Abbott Laboratories. G.G. was a recipient of a Career Award from the Italian Fondazione Cariverona Progetto Sanità.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adrian P V, Klugman K P. Mutations in the dihydrofolate reductase gene of trimethoprim-resistant isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;41:2406–2413. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.11.2406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes D M, Whittie S, Gilligan P H, Soares S, Tomasz A, Henderson F W. Transmission of multidrug-resistant serotype 23F Streptococcus pneumoniae in group day care: evidence suggesting capsular transformation of the resistant strain in vivo. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:890–896. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.4.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beall B, Facklam R R, Jackson D M, Starling H H. Rapid screening for penicillin susceptibility of systemic pneumococcal isolates by restriction enzyme profiling of the pbp2B gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2359–2362. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.8.2359-2362.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coffey T J, Dowson C G, Daniels M, Zhou J, Martin C, Spratt B G, Musser J M. Horizontal transfer of multiple penicillin-binding protein genes, and capsular biosynthetic genes, in natural populations of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:2255–2260. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coffey T J, Dowson C G, Daniels M, Spratt B G. Genetics and molecular biology of beta-lactam-resistant pneumococci. Microb Drug Resist. 1995;1:29–34. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1995.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coffey T J, Berron S, Daniels M, Garcia-Leoni M E, Cercenado E, Bouza E, Fenoll A, Spratt B G. Multiply antibiotic-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae recovered from Spanish hospitals (1988–1994): novel major clones of serotypes 14, 19F and 15F. Microbiology. 1996;142:2747–2757. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-10-2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coffey T J, Enright M C, Daniels M, Wilkinson P, Berron S, Fenoll A, Spratt B G. Serotype 19A variants of the Spanish serotype 23F multiresistant clone of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microb Drug Resist. 1998;4:51–55. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1998.4.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coffey T J, Enright M C, Daniels M, Morona J K, Morona R, Hryniewicz W, Paton J C, Spratt B G. Recombinational exchanges at the capsular polysaccharide biosynthetic locus lead to frequent serotype changes among natural isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:73–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doern G V, Brueggemann A B, Blocker M, Dunne M, Holley H P, Jr, Kehl K S, Duval J, Kugler K, Putnam S, Rauch A, Pfaller M A. Clonal relationships among high-level penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:757–761. doi: 10.1086/514937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dowson C G, Hutchison A, Spratt B G. Extensive re-modelling of the transpeptidase domain of penicillin-binding protein 2B of a penicillin-resistant South African isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:95–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dowson C G, Hutchison A, Brannigan J A, George R C, Hansman D, Linares J, Tomasz A, Smith J M, Spratt B G. Horizontal transfer of penicillin-binding protein genes in penicillin-resistant clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;87:5858–5862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.22.8842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elliott J A, Farmer K D, Facklam R R. Sudden increase in isolation of group B streptococci, serotype V, is not due to emergence of a new pulsed-field gel electrophoresis type. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2115–2116. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.7.2115-2116.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faden H, Duffy L, Wasielewski R, Wolf J, Krystofik D, Tung Y Tonawanda/Williamsville Pediatrics. Relationship between nasopharyngeal colonization and the development of otitis media in children. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:1440–1445. doi: 10.1086/516477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Figueiredo A M, Austrian R, Urbaskova P, Teixeira L A, Tomasz A. Novel penicillin-resistant clones of Streptococcus pneumoniae in the Czech Republic and in Slovakia. Microb Drug Resist. 1995;1:71–78. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1995.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gherardi, G., C. Whitney, R. R. Facklam, and B. Beall. Major clones of β-lactamase resistant pneumococci in the United States based upon PFGE and pbp1a-pbp2b-bpb2x-dhfr fingerprints. Submitted for publication.

- 16.Hall L M C, Whiley R A, Duke B, George R C, Efstratiou A. Genetic relatedness within and between serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae from the United Kingdom: analysis of multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, and antimicrobial resistance patterns. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:853–859. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.4.853-859.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inostroza J, Trucco O, Prado V, Vinet A M, Retamal G, Ossa G, Facklam R R, Sorensen R U. Capsular serotype and antibiotic resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates in two Chilean cities. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1998;5:176–180. doi: 10.1128/cdli.5.2.176-180.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelly T, Dillard J P, Yother J. Effect of genetic switching of capsular type on virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1813–1819. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.1813-1819.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klugman K. Pneumococcal molecular epidemiology network. ASM News. 1998;64:371. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laible G, Hakenbeck R, Sicard M A, Joris B, Ghuysen J M. Nucleotide sequences of the pbpX genes encoding the penicillin-binding proteins 2x from Streptococcus pneumoniae R6 and a cefotaxime-resistant mutant, C506. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:1337–1348. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laible G, Spratt B G, Hakenbeck R. Interspecies recombinational events during the evolution of altered PBP2x genes in penicillin-resistant clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1993–2002. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin C, Briese T, Hakenbeck R. Nucleotide sequences of genes encoding penicillin-binding proteins from Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus oralis with high homology to Escherichia coli penicillin-binding proteins 1A and 1B. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4517–4523. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.13.4517-4523.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDougal L K, Rasheed J K, Biddle J W, Tenover F C. Identification of multiple clones of extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2282–2288. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.10.2282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDougal, L. K., and F. C. Tenover. 1999. Personal communication.

- 25.Mun̈oz R, Coffey T J, Daniels M, Dowson C G, Laible G, Casal J, Hakenbeck R, Jacobs M, Musser J M, Spratt B G. Intercontinental spread of a multiresistant clone of serotype 23F Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 1990;164:302–306. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Munoz R, Musser J M, Crain M, Briles D E, Marton A, Parkinson A J, Sorensen U, Tomasz A. Geographic distribution of penicillin-resistant clones of Streptococcus pneumoniae: characterization by penicillin-binding protein profile, surface protein A typing, and multilocus enzyme analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:112–118. doi: 10.1093/clinids/15.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nesin M, Ramirez M, Tomasz A. Capsular transformation of a multidrug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in vivo. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:707–713. doi: 10.1086/514242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pikis A, Donkershoot J A, Rodriguez W J, Keith J M. A conservative amino acid mutation in the chromosome-encoded dihydrofolate reductase confers trimethoprim resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:700–706. doi: 10.1086/515371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reichmann P, Konig A, Linares J, Alcaide F, Tenover F C, McDougal L, Swidsinski S, Hakenbeck R. A global gene pool for high-level cephalosporin resistance in commensal Streptococcus species and Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1001–1012. doi: 10.1086/516532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sibold C, Wang J, Henrichsen J, Hakenbeck R. Genetic relationships of penicillin-susceptible and -resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae strains isolated on different continents. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4119–4126. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.10.4119-4126.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith A M, Klugman K P. Three predominant clones identified within penicillin-resistant South African isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microb Drug Resist. 1997;3:385–937. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1997.3.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tenover F C, Arbeit R D, Goering R V, Mickelsen P A, Murray B E, Persing D H, Swaminathan B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tomasz A. Antibiotic resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:s85–s88. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.supplement_1.s85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]