Abstract

Background

Low attendance and engagement in behavioural weight management trials are common. Mental health may play an important role, however previous research exploring this association is limited with inconsistent findings. We aimed to investigate whether mental health was associated with attendance and engagement in a trial of behavioural weight management programmes.

Methods

This is a secondary data analysis of the Weight loss referrals for adults in primary care (WRAP) trial, which randomised 1267 adults with overweight or obesity to brief intervention, WW (formerly Weight Watchers) for 12-weeks, or WW for 52-weeks. We used regression analyses to assess the association of baseline mental health (depression and anxiety (by Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale), quality of life (by EQ5D), satisfaction with life (by Satisfaction with Life Questionnaire)) with programme attendance and engagement in WW groups, and trial attendance in all randomised groups.

Results

Every one unit of baseline depression score was associated with a 1% relative reduction in rate of WW session attendance in the first 12 weeks (Incidence rate ratio [IRR] 0.99; 95% CI 0.98, 0.999). Higher baseline anxiety was associated with 4% lower odds to report high engagement with WW digital tools (Odds ratio [OR] 0.96; 95% CI 0.94, 0.99). Every one unit of global quality of life was associated with 69% lower odds of reporting high engagement with the WW mobile app (OR 0.31; 95% CI 0.15, 0.64). Greater symptoms of depression and anxiety and lower satisfaction with life at baseline were consistently associated with lower odds of attending study visits at 3-, 12-, 24-, and 60-months.

Conclusions

Participants were less likely to attend programme sessions, engage with resources, and attend study assessments when reporting poorer baseline mental health. Differences in attendance and engagement were small, however changes may still have a meaningful effect on programme effectiveness and trial completion. Future research should investigate strategies to maximise attendance and engagement in those reporting poorer mental health.

Trial registration

The original trial (ISRCTN82857232) and five year follow up (ISRCTN64986150) were prospectively registered with Current Controlled Trials on 15/10/2012 and 01/02/2018.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12966-021-01216-6.

Keywords: Obesity, Prevention, Weight loss, Mental health, Engagement

Background

Behavioural weight management programmes are internationally recommended practice for the treatment of overweight and obesity [1]. Good evidence shows that behavioural programmes benefit physical health [2–5], and a recent systematic review suggests there may be small benefits for some aspects of mental health, with no evidence to suggest that programmes negatively impact mental health [6]. However, low attendance and engagement with these programmes are common [7, 8], and the reasons for this are poorly understood. Low attendance and engagement can decrease the opportunity for participants to gain the skills, strategies, knowledge, and social support offered by the weight management programmes [8]. Previous research has reported that low levels of attendance and engagement in behavioural weight management programmes are associated with decreased likelihood of achieving clinically significant weight loss, consequently reducing the likelihood of gaining the associated health benefits [9–11], highlighting the importance of better understanding the reasons for poor attendance and engagement.

Previous research has sought to identify factors associated with attendance and engagement in behavioural weight management trials, however, findings have been constrained by the limited diversity of potentially associated factors assessed. Demographic factors, such as age, deprivation, and gender, have been commonly assessed for their association, with evidence suggesting better attendance and engagement among people who are older in age, more educated, and female [12–14]. However, previous research lacks sufficient investigation into how mental health may be associated with attendance and engagement.

Some researchers have suggested that mental health may play an important role in attendance and engagement of behavioural weight management programmes and in attrition of trials evaluating these programmes. There is a well-evidenced bidirectional relationship between obesity and mental health, with poor mental health being both a cause and consequence of obesity [15–20]. Additionally, both obesity and poor mental health are associated with experiencing stigma and discrimination, which is in turn associated with the avoidance of health promoting activities (e.g., behavioural weight management programmes) [21–23]. Furthermore, poor mental health can exacerbate feelings of amotivation [24–26] and can increase the likelihood to socially withdraw and isolate [27–29]. Thus, it is plausible that mental health may be associated with attendance and engagement with a behavioural weight management programme. Mental health is increasingly being considered as a symptom continuum which recognises that individuals can experience one or more symptoms of mental illness without meeting diagnostic criteria [30, 31]. Embracing the symptom continuum-based definition of mental health is associated with reduced stigma and improved attitudes toward mental ill-health [31, 32].

As stated, previous research lacks sufficient investigation into the role of mental health in attendance at and engagement with behavioural weight management programmes. The findings of the limited existing research findings are conflicting with some evidence reporting lower attendance and completion rates among weight management participants with higher levels of anxiety or depression [13, 33, 34], whilst other research reports mental health to not be associated with attendance and engagement [35]. A systematic review reported not finding any consistently associated psychological factors, though these findings were limited by the small number of studies assessing each factor [7]. The limited previous research and conflicting evidence highlights a need for further research investigating the relationship between mental health and attendance at and engagement with behavioural weight management programmes.

It is also plausible that mental health may influence whether a participant attends study follow-up visits. This is important as, although on average mental health appears to improve following a behavioural weight management programme [6], if baseline mental health is associated with attrition then it is possible that this finding may be biased by unrepresentative participant samples. Participant samples may be biased to include the most mentally healthy participants, and this would minimise the generalisability of evidence produced from weight management trials, particularly when assessing the impact of weight management programmes on mental health. We must investigate how participant mental health influences attendance at follow-up assessments for behavioural weight management trials to determine whether participant samples accurately reflect the true range of mental health experiences.

The current study aimed to investigate whether baseline mental health was associated with attendance and engagement with a behavioural weight management programme and completion of follow-up assessments in a randomised controlled trial. By better understanding the influence of baseline mental health on attendance and engagement, appropriate strategies may be implemented to support participation, minimise attrition, and subsequentially benefit health. In this study, we embrace the continuum-based definition of mental health which appreciates that individuals can experience one or more symptoms of mental illness without meeting diagnostic criteria [30, 31].

Methods

Study design

This study is a secondary data analysis of the Weight loss Referrals for Adults in Primary care (WRAP) trial, a non-blinded, multi-arm, randomised controlled trial comparing three intervention arms: (1) Brief intervention (BI), (2) 12-weeks commercial weight management programme (CP12), (3) 52-weeks commercial weight management programme (CP52). Participants who met eligibility criteria and gave informed consent were randomly assigned to an intervention arm on a 2:5:5 ratio with a block size of 12, stratified by research centre and gender. More detailed trial methods are reported elsewhere [36]. Ethical approval up to two year post randomisation follow up was received by East of England Cambridge East with local approvals from NRES Committee North West Liverpool Central and NRES Committee South Central Oxford. Ethical approval for five years post randomisation follow-up was received from West Midlands- Coventry and Warwickshire Research Ethics Committee 8th December 2017. The original trial (ISRCTN82857232) and 5 year follow up (ISRCTN64986150) were prospectively registered with Current Controlled Trials on 15/10/2012 and 01/02/2018 (10.1186/ISRCTN82857232;10.1186/ISRCTN64986150).

Participants

Adults with a body mass index of 28 kg/m2 or greater were identified and recruited by local primary care practices across England. Exclusion criteria were: planned or current pregnancy in the next two years, previous or planned bariatric surgery, currently following a weight loss programme, non-English Speaking or communication needs that would preclude them from understanding the study materials and interventions, and general practitioner-defined inappropriate for participation (e.g., patients who are violent/terminally ill/have a history of an eating disorder). All participants gave written informed consent.

Intervention

Participants randomly assigned to CP12 or CP52 were provided with vouchers to attend a weekly local WW (formerly Weight Watchers) meeting for the duration of the intervention they were assigned to (12-weeks or 52-weeks). Participants were provided with a unique code to access the WW digital tools for the duration of their assigned intervention. Participants assigned to the brief intervention control group were given a 32-page printed booklet by the British Heart Foundation of self-help weight-management strategies [37]. Research staff read a scripted booklet introduction to the participant.

Outcomes

Study participants completed outcome assessments at baseline, 3-, 12-, 24- and 60-months. The outcomes of interest in this study were:

Attendance at WW sessions (i.e., programme attendance): defined as the number of weekly WW sessions attended in the first 3 months of the programme (possible range of 0 to 12). Attendance at WW sessions were categorised as low (≤ 4 sessions), moderate (> 4 and ≤ 8 sessions), or high (> 8 and ≤ 12 sessions) attendance. Programme attendance was calculated by data collected by WW at weekly meetings (participants were provided booklets of vouchers to attend meetings, and WW reported how many vouchers were used). Data related to vouchers issued during a specific time period were not recorded due to a computer system error; as the only difference between those with and without data was referral date, missing data was considered to be missing at random.

Engagement with WW digital tools (i.e., programme engagement): defined as (1) weekly frequency of use of the WW e-tools and online resources and (2) weekly frequency of use of the WW mobile phone app. The WW e-tools are an online service that includes access to support materials (e.g., recipes, videos, community area) and tracking tools. Engagement with digital tools was self-reported at 3-months from baseline, and answers were multiple choice (coded [1] Daily/almost daily, [2] 3–5 times per weeks, [3] 1–2 times per week, [4] Never/almost never).

Study attendance (i.e., study visit attendance): defined as attendance at study clinic visits at 3-, 12-, 24- and 60-month follow-up assessments. Study attendance was monitored by the research team and categorised as (1) did attend visit or (2) did not attend visit.

Exposure variables were mental health-related measures at baseline, including quality of life (measured by EQ5D) [38], satisfaction with life (measured by the Satisfaction with Life Questionnaire (SLQ)) [39], and depression and anxiety (measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)) [40].

The EQ5D, used to measure quality of life, has 5 dimensions ([1] Mobility, [2] Self-care, [3] Usual activities, [4] Pain/discomfort, [5] Anxiety/depression) which are rated on 3 levels of severity (Level 1: No problem, Level 2: Some problems, Level 3: Extreme problems) [38]. Scores for the individual dimensions are collated to create a single index score; we used the UK value set and algorithm to calculate the index scores used. Potential index scores range from −0.281 to 1, where an index score less than 0 represents a state worse than death [41]. The EQ5D is a continuous measure derived from a validated questionnaire and is commonly used measure [38].

The Satisfaction with Life Questionnaire (SLQ) is a 5-item, 7-point scale ([1] strongly disagree to [7] strongly agree) that measures an individuals’ perception of their satisfaction with their life as a whole, allowing the individual to combine and weight aspects contributing to life satisfaction (e.g., health, finances, socialisation) according to their own criteria and judgement [39, 42, 43]. The SLQ score is calculated by adding the scores for each of the 5-items, with a higher total score representing a greater sense of life satisfaction [39]. The SLQ is a valid and reliable scale, with suitability for a wide range of population groups [42, 43].

The HADS measure is a validated screening tool for anxiety and depression with 14 items (1:1 ratio for anxiety:depression) scored on a Likert scale from 0 to 3 [40, 44, 45]. The scale produces symptom scores for anxiety and depression that range from 0 to 21, with a score of equal to or greater than 11 representing moderate to severe symptoms of depression and/or anxiety [40, 44, 45]. The scale cannot provide a clinical diagnosis of anxiety or depression [40, 44, 45]. The recent core outcome set for trials of behavioural adult weight management recommends the inclusion of the HADS measure to strengthen the consistency of reporting across trials [46].

Statistical analysis

Stata (version 16; College Station, TX) [47] was used for all statistical analyses. The aims of this secondary analysis were determined a-priori and comprehensive statistical analyses plan determined prior to obtaining the trial data. Descriptive summary statistics were calculated for baseline characteristics by randomised group, with number of participants, mean, and standard deviation presented for continuous variables and number and proportion of participants presented for categorical variables.

Association of mental health with programme attendance and engagement

Negative binomial regression was used to estimate the effect of participant mental health on programme attendance, controlling for randomised group. Ordered logistic regression was used to estimate the effect on engagement with digital tools, controlling for randomised group. In the ordered logistic regression models, engagement response options were categorised as (1) Daily/Almost daily, (2) 3–5 times per week, (3) 1–2 times per week, and (4) Never/Almost never. Therefore, results were interpreted as the reduction in engagement associated with every unit change in mental health outcome. Analyses were performed using data from the intervention groups only (CP12 and CP52), and robust standard errors were calculated in all models to allow for clustering by general practice.

Association of mental health with study visit attendance

Logistic regression was used to estimate the association between baseline participant mental health and attendance at study follow-up visits (at 3-, 12-, 24-, and 60-months), controlling for randomised group and with robust standard errors to allow for clustering by general practice. Baseline mental health variables whose p-value for association with study visit attendance was < 0.05 were included in mutually adjusted models. Analyses were conducted using data from both intervention and control groups.

Results

Baseline characteristics

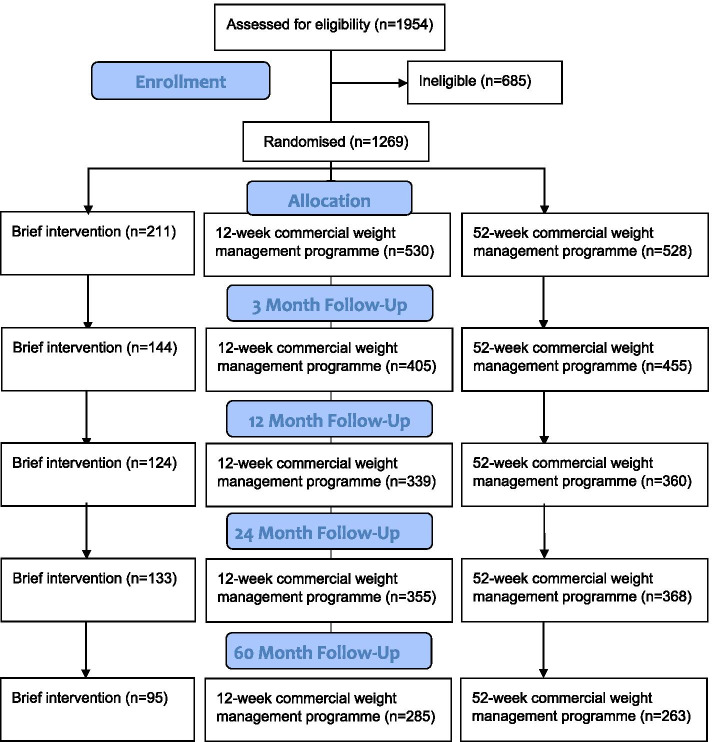

Between 18 October 2012 and 10 February 2014, 1269 eligible participants were randomised to one of three groups. Two participants were excluded after the baseline appointment and prior to the intervention started due to illnesses that rendered them ineligible for the trial. Figure 1 shows the participant flow through the trial. Participant characteristics at baseline are presented by randomised group in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Participant flow diagram (CONSORT)

Table 1.

Participant characteristics at baseline by randomised group

| Baseline characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BI (n = 211) | CP12 (n = 528) | CP52 (n = 528) | ||

| Age (years) [mean ± SD] | 51.91 ± 14.07 | 53.63 ± 13.26 | 53.30 ± 13.96 | |

| Female | 143 (68%) | 357 (68%) | 359 (68%) | |

| Body mass index (BMI: kg/m2) [mean ± SD] | 34.43 ± 4.63 | 34.68 ± 5.39 | 34.45 ± 5.05 | |

| Self-reports taking antidepressant medication | 26 (19%) | 81 (21%) | 81 (23%) | |

| Anxiety [mean ± SD] | 7.25 ± 4.29 | 6.89 ± 3.97 | 7.29 ± 4.09 | |

| Depression [mean ± SD] | 5.58 ± 3.77 | 5.24 ± 3.38 | 5.20 ± 3.64 | |

| Ethnicity | White or White British | 181 (86%) | 480 (91%) | 475 (90%) |

| Asian or Asian British | 9 (4%) | 11 (2%) | 15 (3%) | |

| Black or Black British | 5 (2%) | 12 (2%) | 6 (1%) | |

| Mixed or multiple ethnic group | 4 (2%) | 4 (1%) | 7 (1%) | |

| Other, missing, or prefer not to say | 12 (6%) | 21 (4%) | 25 (4%) | |

| Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) decile | 1 (least deprived) | 16 (8%) | 45 (9%) | 44 (8%) |

| 2 | 8 (4%) | 16 (3%) | 26 (5%) | |

| 3 | 12 (6%) | 38 (7%) | 32 (6%) | |

| 4 | 17 (8%) | 37 (7%) | 38 (8%) | |

| 5 | 31 (15%) | 49 (9%) | 50 (10%) | |

| 6 | 19 (9%) | 61 (12%) | 57 (11%) | |

| 7 | 32 (15%) | 67 (13%) | 63 (12%) | |

| 8 | 19 (9%) | 69 (13%) | 75 (14%) | |

| 9 | 12 (6%) | 51 (10%) | 47 (9%) | |

| 10 (most deprived) | 45 (21%) | 95 (18%) | 94 (18%) | |

| Level of education | None | 7 (3.57%) | 25 (5%) | 27 (6%) |

| GCSE or equivalent | 55 (28%) | 153 (32%) | 155 (33%) | |

| A-Level or equivalent | 53 (27%) | 95 (20%) | 110 (24%) | |

| Post-secondary study | 10 (5%) | 14 (3%) | 10 (2%) | |

| University degree or equivalent | 48 (24%) | 108 (23%) | 97 (21%) | |

| Higher degree or equivalent | 23 (12%) | 79 (17%) | 68 (15%) | |

| Household income | £0–£19,999 | 65 (33%) | 125 (25%) | 138 (28%) |

| £20,000–£49,999 | 66 (33%) | 173 (34%) | 176 (35%) | |

| £50,000+ | 41 (21%) | 91 (18%) | 84 (17%) | |

| Do not know / Prefer not to say | 27 (14%) | 113 (23%) | 101 (20%) | |

Abbreviations: WW Formerly Weight Watchers, BI Brief intervention, CP12–12 week commercial weight management programme (WW), CP52–52 week commercial weight management programme (WW), SD Standard deviation, BMI Body mass index, GCSE General Certificate of Secondary Education, A-Level – Advanced Level Qualification

On average, participants attended approximately 10 out of 12 WW sessions during the first 3-months of the study (12-week programme: 9.63 ± 3.44 sessions (80%); 52-week programme: 9.73 ± 3.41 sessions (81%)) (Table 2). Fifty-six percent of the 12-week programme participants and 50% of the 52-week programme participants never or almost never used the WW e-tools or online resources (Table 2). A high proportion of the study participants never or almost never used the WW mobile phone app (12-week programme: 80%; 52-week programme: 73%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Attendance and engagement with WW interventions, presented by intervention arm

| WW session attendance and engagement with programme resources | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| CP12 | CP52 | ||

|

Attendance at WW sessions in first 3-months (CP12 (n = 272); CP52 (n = 360)) |

Mean number of sessions attended (± SD) | 9.63 ± 3.44 | 9.73 ± 3.41 |

| Low attendance (n %) (≤4 sessions) | 35 (13%) | 55 (15%) | |

| Moderate attendance (n %) (> 4 & ≤ 8 sessions) | 33 (12%) | 29 (8%) | |

| High attendance (n %) (> 8 & ≤ 12 sessions) | 204 (75%) | 276 (77%) | |

|

Frequency of using WW e-tools/online resources (CP12 (n = 355); CP52 (n = 400)) |

Daily/Almost daily | 62 (17%) | 91 (23%) |

| 3–5 times per week | 30 (8%) | 40 (10%) | |

| 1–2 times per week | 63 (18%) | 67 (17%) | |

| Never/Almost never | 200 (56%) | 202 (51%) | |

|

Frequency of using the WW mobile phone app (CP12 (n = 356); CP52 (n = 401)) |

Daily/Almost daily | 35 (10%) | 60 (15%) |

| 3–5 times per week | 15 (4%) | 15 (4%) | |

| 1–2 times per week | 22 (6%) | 32 (8%) | |

| Never/Almost never | 284 (80%) | 294 (73%) | |

Abbreviations: WW formerly Weight Watchers, SD Standard Deviation, CP12–12 week commercial weight management programme (WW), CP52–52 week commercial weight management programme (WW)

The number of participants completing follow-up assessments was 1004 participants at 3-months (79%), 823 participants at 12-months (65%), 856 participants at 24-months (68%), and 643 at 60-months (51%). Reasons for withdrawal from the study are detailed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Reasons for withdrawal from the study, presented by randomised group

| Withdrawal reasons | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| BI (n = 58) | CP12 (n = 110) | CP52 (n = 100) | |

| Changed mind about participating | 12 (21%) | 21 (19%) | 28 (28%) |

| Found another weight loss method | 1 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) |

| Health issues | 5 (9%) | 16 (15%) | 15 (15%) |

| Moved away | 7 (12%) | 17 (15%) | 13 (13%) |

| No reason given | 6 (10%) | 16 (15%) | 9 (9%) |

| Personal reasons | 7 (12%) | 12 (11%) | 14 (14%) |

| Time/other commitments | 6 (10%) | 13 (12%) | 9 (9%) |

| Trouble attending study visits | 0 | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) |

| Unable to attend WW | N/A | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) |

| Unhappy with study procedures | 0 | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) |

| Unhappy with intervention | 14 (24%) | 7 (6%) | 6 (6%) |

Abbreviations: WW Formerly Weight Watchers, BI Brief intervention, CP12–12 week commercial weight management programme (WW), CP52–52 week commercial weight management programme (WW)

Association of mental health with programme attendance and engagement

Association of mental health with attendance at WW sessions

Baseline scores for global quality of life (Incidence rate ratio (IRR) 1.06; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.96, 1.17; n = 608), anxiety (IRR 1.00; 95% CI 0.99, 1.01; n = 625) and satisfaction with life (IRR 1.00; 95% CI 0.999, 1.01; n = 620) were not associated with attendance at WW sessions in the first 3-months (Table 4). Every one unit of baseline depression score was associated with a 1% relative reduction in the rate of session attendance (IRR 0.99; 95% CI 0.98, 0.999; n = 625) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Association of baseline mental health with attendance at WW sessions in first 3-months: Results are presented from negative binomial regression models, controlled for randomised group and with robust standard errors to allow for clustering by general practice

| Attendance at WW sessions in first 3-months | ||

|---|---|---|

| Mental health at baseline: | Incidence rate ratio (95% CI) | Number of participants |

| Model 1: Global quality of life | 1.06 (0.96, 1.17) | 608 |

| Model 2: Satisfaction with life | 1.00 (0.999, 1.01) | 620 |

| Model 3: Anxiety | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 625 |

| Model 4: Depression | 0.99 (0.98, 0.999) | 625 |

Abbreviations: WW Formerly Weight Watchers, CI Confidence interval

Association of mental health with programme engagement

Baseline scores for global quality of life (Odds Ratio (OR) 0.65; 95% CI 0.39, 1.09; n = 728), satisfaction with life (OR 1.01; 95% CI 0.99, 1.03; n = 743), and depression (OR 1.00; 95% CI 0.97, 1.04; n = 747) were not associated with weekly frequency of using WW e-tools/online resource (Table 5). Participants’ baseline score for anxiety was associated with self-reported engagement with the WW e-tools and online resources; every one unit of baseline anxiety was associated with 4% lower odds of reporting high levels of engagement with the WW e-tools and online resources (OR 0.96; 95% CI 0.94, 0.99; n = 747) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Association of baseline mental health with weekly use of WW digital resources in first 3 months: Results are presented from negative binomial regression models, controlled for randomised group and with robust standard errors to allow for clustering by general practice

| Weekly frequency of using WW e-tools/online resources (reported at 3-months) | ||

| Mental health at baseline: | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Number of participants |

| Model 1: Global quality of life | 0.65 (0.39, 1.09) | 728 |

| Model 2: Satisfaction with life | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 743 |

| Model 3: Anxiety | 0.96 (0.94, 0.99) | 747 |

| Model 4: Depression | 1.00 (0.97, 1.04) | 747 |

| Weekly frequency of using the WW mobile phone app (reported at 3-months) | ||

| Mental health at baseline: | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Number of participants |

| Model 1: Global quality of life | 0.31 (0.15, 0.64) | 730 |

| Model 2: Satisfaction with life | 1.02 (0.996, 1.04) | 745 |

| Model 3: Anxiety | 0.98 (0.95, 1.02) | 749 |

| Model 4: Depression | 1.00 (0.96, 1.05) | 749 |

Abbreviations: WW formerly Weight Watchers, CI Confidence interval

Association of mental health with engagement with WW mobile phone app

Anxiety (OR 0.98; 95% CI 0.95, 1.02; n = 749), depression (OR 1.00; 95% CI 0.96, 1.05; n = 749) and satisfaction with life (OR 1.02; 95% CI 0.996, 1.04; n = 745) at baseline were not associated with weekly frequency of using the WW mobile phone app (Table 5). Every one unit of baseline global quality of life was associated with 69% lower odds of reporting high levels of weekly engagement with the WW mobile phone app (OR 0.31; 95% CI 0.15, 0.64; n = 730).

Association of mental health with study visit attendance

Association of mental health with attendance at 3-month study visit

Every one unit of baseline global quality of life (OR 1.95; 95% CI 1.20, 3.17; n = 1209) and baseline satisfaction with life (OR 1.02; 95% CI 1.00, 1.04; n = 1209) were associated with a 95% and 2% higher odds of attending the 3-month study visit respectively. Conversely, every one unit of baseline anxiety (OR 0.95; 95% CI 0.92, 0.98; n = 1209) and baseline depression (OR 0.93; 95% CI 0.89, 0.97; n = 1209) were associated with a 5% and 7% lower odds of attending the 3-month study visit (Table 6).

Table 6.

Influence of baseline mental health on attendance at study follow-up visits: Results are presented from unadjusted and mutually adjusted logistic regression models. Mutually adjusted models are adjusted for baseline mental health variables that were statistically significant in unadjusted models. Baseline mental health variables that were not statistically significant in unadjusted models were not adjusted for in mutually adjusted models. All models were controlled for randomised group and clustering by general practice

| Mental health at baseline: | Attendance at 3-month study visit (Odds ratio (95% CI)) | |

| Unadjusted logistic regression (n = 1209) | Mutually adjusted logistic regression (n = 1196) | |

| Global quality of life | 1.95 (1.20, 3.17) | 1.25 (0.67, 2.30) |

| Satisfaction with life | 1.02 (1.00, 1.04) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.02) |

| Anxiety | 0.95 (0.92, 0.98) | 0.99 (0.94, 1.04) |

| Depression | 0.93 (0.89, 0.97) | 0.94 (0.87, 1.01) |

| Mental health at baseline: | Attendance at 12-month study visit (Odds ratio (95% CI)) | |

| Unadjusted logistic regression (n = 1227) | Mutually adjusted logistic regression (n = 1224) | |

| Global quality of life | 1.48 (0.93, 2.37) | ^^ |

| Satisfaction with life | 1.02 (1.00, 1.04) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.03) |

| Anxiety | 0.94 (0.91, 0.97) | 0.96 (0.92, 1.00) |

| Depression | 0.94 (0.91, 0.98) | 0.97 (0.93, 1.02) |

| Mental health at baseline: | Attendance at 24-month study visit (Odds ratio (95% CI)) | |

| Unadjusted logistic regression (n = 1237) | Mutually adjusted logistic regression (n = 1224) | |

| Global quality of life | 1.61 (0.97, 2.66) | ^^ |

| Satisfaction with life | 1.03 (1.00, 1.05) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.04) |

| Anxiety | 0.94 (0.91, 0.97) | 0.95 (0.91, 0.98) |

| Depression | 0.95 (0.91, 1.00) | 1.00 (0.95, 1.06) |

| Mental health at baseline: | Attendance at 60-month study visit (Odds ratio (95% CI)) | |

| Unadjusted logistic regression (n = 1237) | Mutually adjusted logistic regression (n = 1196) | |

| Global quality of life | 2.02 (1.27, 3.23) | 1.41 (0.83, 2.38) |

| Satisfaction with life | 1.03 (1.00, 1.05) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) |

| Anxiety | 0.95 (0.92, 0.98) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.02) |

| Depression | 0.94 (0.91, 0.97) | 0.97 (0.92, 1.03) |

Note: ^^ Not included in mutually adjusted model

Abbreviations: CI Confidence interval

Baseline quality of life, satisfaction with life, anxiety, and depression were not associated with attendance at the 3-month study visit in the mutually adjusted model (Table 6).

Association of mental health with attendance at 12-month study visit

Baseline global quality of life was not associated with attendance at the 12-months study visit (OR 1.48; 95% CI 0.93, 2.37; n = 1227). A unit higher baseline satisfaction with life score was associated with 2% higher odds of attending the 12-month study visit (OR 1.02; 95% CI 1.00, 1.04; n = 1227). A unit higher anxiety (OR 0.94; 95% CI 0.91, 0.97; n = 1227) and baseline depression (OR 0.94; 95% CI 0.91, 0.98; n = 1227) score at baseline were associated with a 6% lower odds of attending the 12-month study visit (Table 6). Baseline satisfaction with life, anxiety, and depression were not associated with attendance at the 12-month study visit in the mutually adjusted model (Table 6).

Association of mental health with attendance at 24-month study visit

Baseline global quality of life was not associated with attendance at the 24-months study visit (OR 1.61; 95% CI 0.97, 2.66; n = 1237). A unit higher baseline satisfaction with life score was associated with a 3% increase in odds of attending the 24-month study visit (OR 1.03; 95% CI 1.00, 1.05; n = 1237). A unit higher baseline anxiety (OR 0.94; 95% CI 0.91, 0.97; n = 1237) and depression (OR 0.95; 95% CI 0.91, 0.997; n = 1237) scores were associated with a 6% and 5% lower odds of attending the 24-month study visit (Table 6).

Baseline satisfaction with life and baseline depression did not remain associated with attendance at the 24-month study visit when adjusted for baseline anxiety and depression (Table 6). When adjusted for baseline satisfaction with life and depression, a unit in baseline anxiety was associated with a 5% decrease in odds of attending the 24-month visit (OR 0.95; 95% CI 0.91, 0.98); n = 1196).

Association of mental health with attendance at 60-month study visit

A unit higher baseline global quality of life (OR 2.02; 95% CI 1.27, 3.23; n = 1237) and satisfaction with life (OR 1.03; 95% CI 1.00, 1.05; n = 1237) scores were associated with a 102% and 3% increase in odds of attending the 60-month study visit. Conversely, a unit higher baseline anxiety (OR 0.95; 95% CI 0.92, 0.98; n = 1237) and depression (OR 0.94; 95% CI 0.91, 0.97; n = 1237) scores were associated with a 5% and 6% decrease in odds of attending the 60-month study visit (Table 6). Baseline quality of life, satisfaction with life, anxiety, and depression were not associated with attendance at the 60-month study visit in the mutually adjusted model (Table 6).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated whether participants’ mental health was associated with the rate of attendance and engagement with the behavioural weight management programme (WW) and trial (WRAP). Lower levels of depression symptoms and higher scores for satisfaction with life at baseline were associated with higher rates of attendance at WW sessions (i.e., higher rates of programme attendance). Similarly, adults with obesity who reported experiencing fewer symptoms of depression and anxiety and a higher satisfaction with life at baseline were more likely to report higher engagement with the programme resources (WW e-tools and mobile phone app). We also found that those reporting greater quality of life at baseline were likely to have lower engagement with the WW mobile phone app than those with poorer quality of life, however this association was not consistent across study findings. Higher scores for quality of life and satisfaction with life and fewer symptoms of depression and anxiety were also associated with higher attendance at all study visits up to 5 years follow-up.

Overall, we found that adults with obesity who self-reported being more mentally healthy at baseline were more likely to attend programme sessions, engage with programme resources, and attend study follow-up assessments. Previous research has reported that low levels of attendance and engagement in behavioural weight management trials are associated with decreased likelihood of achieving clinically significant weight loss, consequently reducing the likelihood of gaining the associated health benefits [9–11]. These findings highlight an emerging research priority to explore how to maximise the engagement and retention of people experiencing poorer mental health.

It is important to note, however, that study findings should be interpreted with consideration to the loss of significance in mutually adjusted models and the magnitude of the effect sizes presented. Many significant associations in univariable models became non-significant when mutually adjusted, potentially due to the mental health-related exposure variables being moderately correlated (Additional file 1: Table S1). Cross-correlation of exposure variables found correlations to range between small and large, with measures of anxiety and depression most highly correlated. Future research may consider the use of a composite indicator by combining individual measures into a single index, therefore reducing the impact of multicollinearity. The effect sizes of the associations between mental health and attendance and engagement were considered to be small, suggesting a small increase in risk of reporting lower attendance and engagement when reporting poor mental health at baseline [48]. However, these changes may still have a meaningful effect on the effectiveness of the behavioural weight management programme and trial. More research is needed to confirm the size of effect and investigate the potential impact on programme effectiveness and health outcomes.

Previous systematic review evidence has found no consistent psychological factors to be associated with attendance and engagement, but recommended further research into this area [7]. In the current study, we found poorer rates of attendance and engagement in those with poor mental health scores at baseline, aligning with the findings of McLean and colleagues who reported lower attendance among participants with higher levels of anxiety or depression [33]. Furthermore, current findings also align with previous research reporting those with higher levels of anxiety or depression are more likely to report worse attendance and engagement with the weight management trial [13, 34]. Some previous research, however, has reported finding mental health to not be associated with attendance and engagement [14, 35], contrasting with the findings of the current study. This may be due to the differing classification of mental health within different studies. For example, Funderburk and colleagues defined mental health as diagnosed versus non-diagnosed with mental illness [35], whereas we considered mental health as a symptom-continuum which appreciates that participants can experience one or more symptoms of mental illness without meeting diagnostic criteria [30, 31]. This approach was selected as it is associated with reduced stigma, and enables the investigation of a broader range of mental health outcomes [30–32].

There are many reasons why mental health might influence attendance and engagement with a behavioural weight management programme. Having poor mental health can make participation and engagement difficult and, in particular, can make it difficult to engage in things that may interfere with self-soothing coping strategies (e.g., emotional eating) [49]. Many adults with obesity seek social support and socialisation from WW groups [50]. For those living with poor mental health, forming connections with others can be impeded by an increased likelihood to withdraw/isolate, be less vulnerable with others when forming connections, and be more likely perceive others to judge them poorly (i.e., self-conscious/lacking self-esteem) [50]. In turn, those living with obesity and mental ill-health are likely to experience greater difficulties to connect with peers at the WW group than those who are mentally healthy, thus reducing the likelihood of programme attendance as their hopes and expectations of social support are not met. Previous negative experiences with healthcare providers (e.g., experiencing blame, shame, and discrimination for weight and/or mental health) may have reduced trust in services and healthcare staff, resulting in reduced engagement with services [49, 51]. Participants may also find that lack of immediate weight changes emphasises feelings of failure and shame, reduces their confidence in services’ effectiveness [52–55], and results in feelings of disappointment with the programme content [53]. Understandably, these feelings may decrease their motivation to attend the programme sessions.

Future research could use qualitative approaches to explore the mechanisms underpinning why those with poor mental health are less likely to attend and engage with behavioural weight management programmes. The mechanisms influencing programme attendance and engagement may be individual-level, societal-level, or operate across multiple levels. Understanding of these mechanisms would enable development of approaches to combat this issue. Furthermore, future research might explore whether tailoring programmes for those with obesity and poor mental health may result in improved programme attendance and engagement. For example, the RAINBOW trial provided a tailored weight management programme for persons with obesity and depression, finding modest improvements in both weight and depression symptoms [56]. We are unaware, however, if the tailored programme resulted in greater attendance and engagement rates than similar individuals attending a standard behavioural weight management programme.

The findings of the current study suggest that follow-up participant samples are less likely to include people with poorer mental health at baseline. Potential explanations may be higher levels of anxiety regarding clinical assessments (e.g., blood-sampling), lack of confidence in trial effectiveness (e.g., lack of immediate results), discomfort answering personal questionnaires (e.g., psychological assessments), and perceived participant burden (e.g., unhappy with length of questionnaires about mental health) [57–59]. Previous evidence from behavioural weight management trials should not be discarded, however caution should be taken when interpreting findings. In future trials, researchers should consider implementing a participant retention strategy that supports those with poorer mental health at baseline.

Strengths and limitations

It is uncommon for behavioural weight management trials to measure and report mental health outcomes [6]. This secondary analysis of the WRAP trial benefited from the inclusion of multiple mental health outcomes at each assessment. Study findings were limited to those mental health measures implemented in the WRAP trial, the primary focus of which was the impact on weight and related outcomes [36]. Mental health measures not collected in this trial may further explain participant attendance and engagement rates, such as social support, stress, loneliness, self-esteem, and self-efficacy. Future research should aim to measure a wide range of mental health outcomes, but this must be balanced against participant burden.

A limitation was the large proportion of missing data, specifically for attendance at WW sessions and engagement with the WW resources. We had pre-specified a sensitivity analysis using multiple imputation, but also pre-specified that this would not be appropriate if the level of missingness were 25% or more (as it was for the programme attendance and engagement analyses), and would not be necessary if the level of missingness were less than 5% (as it was for the analysis of study attendance).

In addition, it is worth noting that engagement with WW digital resources and the mobile phone app was assessed using a self-report questionnaire and is therefore subject to potential error and bias, such as recall error and social desirability bias. To increase the accuracy of engagement data going forward, we recommend the use of objective measures either in replacement or in combination with self-report measures.

Despite these limitations, this study contributes new evidence to the field by seeking to understand the factors impacting attendance and engagement in behavioural weight management trials. To our knowledge, this study is one of the first to explicitly focus on the impact of mental health on programme and study attendance and engagement. We investigated the impact of participant mental health on numerous attendance and engagement factors and found relatively consistent evidence across factors. The aims of this secondary analysis were determined a priori, with a comprehensive statistical analyses plan determined prior to obtaining the trial data. The WRAP trial benefits from the randomised controlled trial design and minimal eligibility criteria that increase the representative nature of the baseline participant sample relative to the general population of adults with obesity in the UK.

Conclusions

This study shows that adults with obesity attending a behavioural weight management programme are less likely to attend programme sessions, engage with programme resources, and attend study follow-up visits if they report higher levels of depression and anxiety, and lower scores for quality of life and satisfaction with life at baseline. The small effect sizes reported suggest a small increase in odds of low attendance and engagement in those experiencing poor mental health at baseline, however the changes may still have a meaningful effect on programme effectiveness and trial completion. Lower attendance and engagement are associated with reduced likelihood of achieving clinically significant weight loss and the associated health benefits, highlighting the importance of maximising participant attendance and engagement in behavioural weight management programmes. Future research should explore the effectiveness of targeted strategies to maximise attendance and engagement in those reporting poorer mental health upon entering a behavioural weight management programme or trial. Additionally, researchers should ensure to apply appropriate caution when interpreting trial findings, and sufficiently control for potential bias due to mental health when conducting trial analyses.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge their Co-Investigators on the WRAP trial (Paul Aveyard, Emma Boyland, Simon Cohn, Jason Halford, Susan Jebb, Adrian Mander, Marc Suhrcke) and the WRAP 5 year follow up (Andrew Hill, Alan Brennan, Ed Wilson, Brett Doble, Carly Hughes, Jennifer Bostock) who contributed to obtaining funding and the design and conduct of the trial and follow up, as well as the trial managers (Jennifer Woolston and Ann Thomson) and the research staff who facilitated participant recruitment and follow up. We would like to thank the participants of the WRAP trial for their participation in the study. We would also like to thank Clare Boothby for supporting data management.

Abbreviations

- A-Level

Advanced Level Qualification

- BI

Brief intervention

- BMI

Body mass index

- CI

Confidence Interval

- GCSE

General Certificate of Secondary Education

- CP12

12-weeks commercial weight management programme

- CP52

52-weeks commercial weight management programme

- HADS

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- IMD

Index of Multiple Deprivation

- IRR

Incidence Rate Ratio

- OR

Odds Ratio

- SD

Standard Deviation

- SLQ

Satisfaction with Life Questionnaire

- WRAP

Weight loss Referrals for Adults in Primary care trial

- WW

(formerly) Weight Watchers

Authors’ contributions

RAJ designed the study, analysed and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. JM and SJS contributed to the design of the study, interpretation of the data, and critically reviewed the manuscript. RD and SJG provided critical appraisal of the study and manuscript. AV contributed to the interpretation of the data and critically reviewed the manuscript. AA designed and supervised the study, interpreted the data and critically appraised and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The WRAP trial was funded by the National Prevention Research Initiative through research grant MR/J000493. The intervention was provided by WW (formerly Weight Watchers) at no cost via an MRC Industrial Collaboration Award. Five year follow up of the WRAP trial was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research Programme (RP-PG-0216-20010). RAJ, ALA, SJG, and SJS are supported by the Medical Research Council (MRC) (Grant MC_UU_00006/6). The University of Cambridge has received salary support in respect of SJG from the National Health Service in the East of England through the Clinical Academic Reserve. All funding bodies had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, and in the writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset analysed during the current study is not publicly available. Participant consent allows for data to be shared in future analyses with appropriate ethical approval, and the host institution have an access policy (https://www.mrc-epid.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Data-Access-Sharing-Policy-v1-0_FINAL.pdf) so that interested parties can obtain the data for replication or other research purposes that are ethically approved. Data access is available from the senior author, who is also the principal investigator of the WRAP trial, upon reasonable request (ala34@cam.ac.uk).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for up to 2 year post randomisation assessment was received by East of England Cambridge East and local approvals from NRES Committee North West Liverpool Central and NRES Committee South Central Oxford. Ethical approval for 5 years post randomisation assessment was received from West Midlands- Coventry and Warwickshire Research Ethics Committee 8th December 2017. The original trial (ISRCTN82857232) and 5 year follow up (ISRCTN64986150) were prospectively registered with Current Controlled Trials on 15/10/2012 and 01/02/2018 (10.1186/ISRCTN82857232; 10.1186/ISRCTN64986150).

Consent for publication

At enrolment, a member of the research team trained in taking informed consent ensured participants understood the trial and had read the participant information sheet. All participants provided written informed consent for their participation in the trial.

Competing interests

RAJ, JM, RD and SS declare that they have no competing interests. ALA and SJG are the principal investigators on two publicly funded (MRC, NIHR) trials where the intervention is provided by WW (formerly Weight Watchers) at no cost outside the submitted work.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Semlitsch T, Stigler FL, Jeitler K, Horvath K, Siebenhofer A. Management of overweight and obesity in primary care—a systematic overview of international evidence-based guidelines. Obes Rev. 2019;20(9):1218–1230. doi: 10.1111/obr.12889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tuomielhto J, Lingstrom J, Eriksson J, Valle T, Hamalainen H, Ilanne-Parikka P, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2008;344(18):1343–1350. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmad Zamri L, Appannah G, Zahari Sham SY, Mansor F, Ambak R, Mohd Nor NS, et al. Weight change and its association with cardiometabolic risk markers in overweight and obese women. J Obes. 2020; Available from: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/jobe/2020/3198326/?utm_source=researcher_app&utm_medium=referral&utm_campaign=RESR_MRKT_Researcher_inbound. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Wing RR, Lang W, Wadden TA, Safford M, Knowler WC, Bertoni AG, et al. Benefits of modest weight loss in improving cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(7):1481–1486. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones RA, Lawlor ER, Birch JM, Patel MI, Werneck AO, Hoare E, et al. The impact of adult behavioural weight management interventions on mental health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2020:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Moroshko I, Brennan L, O’Brien P. Predictors of dropout in weight loss interventions: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2011;12(11):912–934. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pirotta S, Joham A, Hochberg L, Moran L, Lim S, Hindle A, et al. Strategies to reduce attrition in weight loss interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2019;20(10). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Johnston CA, Moreno JP, Hernandez DC, Link BA, Chen TA, Wojtanowski AC, et al. Levels of adherence needed to achieve significant weight loss. Int J Obes. 2019;43(1):125–131. doi: 10.1038/s41366-018-0226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stubbs RJ, Morris L, Pallister C, Horgan G, Lavin JH. Weight outcomes audit in 1.3 million adults during their first 3 months’ attendance in a commercial weight management programme. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2225-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stubbs RJ, Brogelli DJ, Pallister CJ, Whybrow S, Avery AJ, Lavin JH. Attendance and weight outcomes in 4754 adults referred over 6 months to a primary care/commercial weight management partnership scheme. Clin Obes. 2012;2(1–2):6–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-8111.2012.00040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blane DN, McLoone P, Morrison D, MacDonald S, O’Donnell CA. Patient and practice characteristics predicting attendance and completion at a specialist weight management service in the UK: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(11):1–9. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leung AWY, Chan RSM, Sea MMM, Woo J. An overview of factors associated with adherence to lifestyle modification programs for weight management in adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Elfhag K, Rössner S. Initial weight loss is the best predictor for success in obesity treatment and sociodemographic liabilities increase risk for drop-out. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;79(3):361–366. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geiker NRW, Astrup A, Hjorth MF, Sjödin A, Pijls L, Markus CR. Does stress influence sleep patterns, food intake, weight gain, abdominal obesity and weight loss interventions and vice versa? Obes Rev. 2018;19(1):81–97. doi: 10.1111/obr.12603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bak M, Fransen A, Janssen J, van Os J, Drukker M. Almost all antipsychotics result in weight gain: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94112. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fruh SM. Obesity: risk factors, complications, and strategies for sustainable long-term weight management. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2017;29:S3–14. doi: 10.1002/2327-6924.12510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fabricatore A, Wadden T, Higginbotham A, Faulconbridge L, Nguyen A, Heymsfield S, et al. Intentional weight loss and changes in symptoms of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes. 2011;35(11):1363–1376. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKibbin CL, Kitchen KA, Wykes TL, Lee AA. Barriers and facilitators of a healthy lifestyle among persons with serious and persistent mental illness: perspectives of community mental health providers. Community Ment Health J. 2014;50(5):566–576. doi: 10.1007/s10597-013-9650-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization . The European Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization . Weight bias and obesity stigma: considerations for the WHO European Region. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pudney EV, Himmelstein MS, Puhl RM, Foster GD. Distressed or not distressed? A mixed methods examination of reactions to weight stigma and implications for emotional wellbeing and internalized weight bias. Soc Sci Med. 2020;14(249):112854. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kane JC, Elafros MA, Murray SM, Mitchell EMH, Augustinavicius JL, Causevic S, et al. A scoping review of health-related stigma outcomes for high-burden diseases in low- and middle-income countries. BMC Med. 2019;17(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Avila C, Holloway AC, Hahn MK, Morrison KM, Restivo M, Anglin R, et al. An overview of links between obesity and mental health. Curr Obes Rep. 2015;4(3):303–310. doi: 10.1007/s13679-015-0164-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erickson ZD, Kwan CL, Gelberg HA, Arnold IY, Chamberlin V, Rosen JA, et al. A randomized, controlled multisite study of behavioral interventions for veterans with mental illness and antipsychotic medication-associated obesity. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(S1):32–39. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3960-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rouse PC, Ntoumanis N, Duda JL, Jolly K, Williams GC. In the beginning: role of autonomy support on the motivation, mental health and intentions of participants entering an exercise referral scheme. Psychol Health. 2011;26(6):729–749. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2010.492454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santini ZI, Jose PE, York Cornwell E, Koyanagi A, Nielsen L, Hinrichsen C, et al. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans (NSHAP): a longitudinal mediation analysis. Lancet Public Heal [Internet] 2020;5(1):E62–E70. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stafford M, Von Wagner C, Perman S, Taylor J, Kuh D, Sheringham J. Social connectedness and engagement in preventive health services: an analysis of data from a prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Heal. 2018;3(9):E438–E446. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30141-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nuyen J, Tuithof M, de Graaf R, van Dorsselaer S, Kleinjan M, Have M t. The bidirectional relationship between loneliness and common mental disorders in adults: findings from a longitudinal population-based cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2020;55(10):1297–1310. doi: 10.1007/s00127-019-01778-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seow LSE, Chua BY, Xie H, Wang J, Ong HL, Abdin E, et al. Correct recognition and continuum belief of mental disorders in a nursing student population. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1447-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Angermeyer MC, Millier A, Rémuzat C, Refaï T, Schomerus G, Toumi M. Continuum beliefs and attitudes towards people with mental illness: results from a national survey in France. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2015;61(3):297–303. doi: 10.1177/0020764014543312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schomerus G, Angermeyer MC, Baumeister SE, Stolzenburg S, Link BG, Phelan JC. An online intervention using information on the mental health-mental illness continuum to reduce stigma. Eur Psychiatry [Internet] 2016;32:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McLean R, Morrison D, Shearer R, Boyle S, Logue J. Attrition and weight loss outcomes for patients with complex obesity, anxiety and depression attending a weight management programme with targeted psychological treatment. Clin Obes. 2016;6(2):133–142. doi: 10.1111/cob.12136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Somerset SM, Graham L, Markwell K. Depression scores predict adherence in a dietary weight loss intervention trial. Clin Nutr. 2011;30(5):593–598. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Funderburk JS, Arigo D, Kenneson A. Initial engagement and attrition in a national weight management program: demographic and health predictors. Transl Behav Med. 2016;6(3):358–368. doi: 10.1007/s13142-015-0335-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahern AL, Aveyard PN, Halford JC, Mander A, Cresswell L, Cohn SR, et al. Weight loss referrals for adults in primary care (WRAP): protocol for a multi-Centre randomised controlled trial comparing the clinical and cost-effectiveness of primary care referral to a commercial weight loss provider for 12 weeks, referral for 52 week. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):620. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahern AL, Wheeler GM, Aveyard P, Boyland EJ, Webber L, Irvine L, et al. Extended and standard duration weight-loss programme referrals for adults in primary care (WRAP): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2214–2225. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30647-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy (New York) 1996;37(1):53–72. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(96)00822-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess [Internet]. 1985;49(1):71–75. Available from: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Devlin N, Shah K, Feng Y, Mulhern B, van Hout B. Valuing health-related quality of life: an EQ-5D-5L value set for England. Health Econ. 2018;27:7–22. doi: 10.1002/hec.3564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pavot W, Diener E. Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychol Assess. 1993;5(2):164–172. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pavot WG, Diener E, Colvin CR, Sandvik E. Further validation of the satisfaction with life scale: evidence for the cross-method convergence of well-being measures. J Personal Assess. 1991;57:149–161. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5701_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(2):69–77. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jagielski AC, Brown A, Hosseini-Araghi M, Thomas GN, Taheri S. The association between adiposity, mental well-being, and quality of life in extreme obesity. PLoS One. 2014;9(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Mackenzie RM, Ells LJ, Simpson SA, Logue J. Core outcome set for behavioural weight management interventions for adults with overweight and obesity: standardised reporting of lifestyle weight management interventions to aid evaluation (STAR-LITE) Obes Rev. 2020;21(2):1–25. doi: 10.1111/obr.12961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.StataCorp . Stata statistical software: Release 16. College Station: StataCorp LLC; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen H, Cohen P, Chen S. How big is a big odds ratio? Interpreting the magnitudes of odds ratios in epidemiological studies. Commun Stat Simul Comput. 2010;39(4):860–864. [Google Scholar]

- 49.The British Psychological Society . Psychological perspectives on obesity : Addressing policy , practice and research priorities. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zwickert K, Rieger E. A qualitative investigation of obese women’s experiences of effective and ineffective social support for weight management. Clin Obes. 2014;4(5):277–286. doi: 10.1111/cob.12072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roberts Haf S, Bailey Elisabeth J, Roberts SH, Bailey JE. Incentives and barriers to lifestyle interventions for people with severe mental illness: a narrative synthesis of quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods studies. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(4):690–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rand K, Vallis M, Aston M, Price S, Piccinini-Vallis H, Rehman L, et al. “It is not the diet; it is the mental part we need help with.” A multilevel analysis of psychological, emotional, and social well-being in obesity. Int J Qual Stud Health Well Being. 2017;12(1) Available from:. 10.1080/17482631.2017.1306421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Kirk SFL, Price SL, Penney TL, Rehman L, Lyons RF, Piccinini-Vallis H, et al. Blame, shame, and lack of support: a multilevel study on obesity management. Qual Health Res. 2014;24(6):790–800. doi: 10.1177/1049732314529667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garip G, Yardley L. A synthesis of qualitative research on overweight and obese people’s views and experiences of weight management. Clin Obes. 2011;1(2–3):110–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-8111.2011.00021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mold F, Forbes A. Patients’ and professionals’ experiences and perspectives of obesity in health-care settings: a synthesis of current research. Health Expect. 2013;16(2):119–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00699.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ma J, Rosas LG, Lv N, Xiao L, Snowden MB, Venditti EM, et al. Effect of integrated behavioral weight loss treatment and problem-solving therapy on body mass index and depressive symptoms among patients with obesity and depression: the RAINBOW randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321(9):869–879. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grossi E, Dalle Grave R, Mannucci E, Molinari E, Compare A, Cuzzolaro M, et al. Complexity of attrition in the treatment of obesity: clues from a structured telephone interview. Int J Obes. 2006;30(7):1132–1137. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Colombo O, Ferretti VV, Ferraris C, Trentani C, Vinai P, Villani S, et al. Is drop-out from obesity treatment a predictable and preventable event? Nutr J. 2014;13(1):9–11. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-13-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miller BML, Brennan L. Measuring and reporting attrition from obesity treatment programs: a call to action! Obes Res Clin Pract. 2015;9(3):187–202. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The dataset analysed during the current study is not publicly available. Participant consent allows for data to be shared in future analyses with appropriate ethical approval, and the host institution have an access policy (https://www.mrc-epid.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Data-Access-Sharing-Policy-v1-0_FINAL.pdf) so that interested parties can obtain the data for replication or other research purposes that are ethically approved. Data access is available from the senior author, who is also the principal investigator of the WRAP trial, upon reasonable request (ala34@cam.ac.uk).