Abstract

Polymer topology dictates dynamic and mechanical properties of materials. For most polymers, topology is a static characteristic. In this article, we present a strategy to chemically trigger dynamic topology changes in polymers in response to a specific chemical stimulus. Starting with a dimerized PEG and hydrophobic linear materials, a lightly cross-linked polymer, and a cross-linked hydrogel, transformations into an amphiphilic linear polymer, lightly cross-linked and linear random copolymers, a cross-linked polymer, and three different hydrogel matrices were achieved via two controllable cross-linking reactions: reversible conjugate additions and thiol–disulfide exchange. Significantly, all the polymers, before or after topological changes, can be triggered to degrade into thiol- or amine-terminated small molecules. The controllable transformations of polymeric morphologies and their degradation herald a new generation of smart materials.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Stimuli-responsive polymers that are capable of adapting their structure, constitution, and reactivity on receiving an external stimulus have been emerging in various fields of study, such as biology, medicine, and manufacturing.1–4 Currently, the control of their properties has been limited to single chemical functional group interchanges and very limited structural/morphological changes. Similarly, degradable polymers are an important goal within polymer science and have been used in a wide range of applications spanning medicine and drug delivery to microelectronics and environmental protection.5 In 2018, Lamb et al. reported that a billion plastic items are entangled on coral reefs across the Asia-Pacific.6 Thus, it is increasingly critical that plastics and other polymers be triggered to degrade at will.7

The physical properties of polymers are strongly dependent on several features: their molecular weight distribution, tacticity, topology, chemical functionality, and density of cross-linking.8 It is rare that these features can be triggered to change by altering the bonding patterns within the backbone structure, as well as changing cross-linking group functionality, and thereby manipulate material properties. To realize transformations of macromolecular topology, exploiting the reversibility and orthogonality of dynamic covalent chemistry is useful because these reactions enable independent control over differing functional groups in a single chemical system.9–12 As alluded to above, if the orthogonal interactions can be manipulated under physiological conditions (i.e., in neutral aqueous media), they could lead to new therapeutic materials platforms. Further, if the molecular architecture can be morphed under mild conditions, and with the ability to disassemble the soft materials into small molecules on demand, controllable material properties and triggered biodegradation are within reach. Each of these features is described herein.

In the pursuit of such materials, Sumerlin reported that macromolecular metamorphosis via reversible Diels–Alder transformations of polymer architectures can be achieved in organic media at high temperature over a period of a few days.13,14 This exploration of topological interchange was an important step forward because a single system could be converted to several macromolecular architectures depending upon reaction conditions. However, the use of elevated temperatures and organic solvents and the lack of polymer degradation following transformation limit the applications that can be envisioned.

“Click chemistry” is a term used to describe reactions that are high yielding, wide in scope, and create byproducts that can be easily removed.15–17 The Cu(I)-catalyzed azide/alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) “click” reaction has been used extensively in the field of polymer science.18–20 Recently, our group reported an alternative click strategy and an associated chemically triggered “declick”, which involves the coupling of amines and thiols via conjugate acceptor 1, which functions in both aqueous and organic media21,22 (Scheme 1). The two thioethers in 1 can be released using various reagents,23 and amine/thiol conjugates such as 2 could be declicked with dithioltreitol (DTT). Noticeably, decoupling of conjugate acceptor 1 releases two equivalents of thiol, which can facilitate thiol—disulfide exchange reactions.23–25 Thus, we envisioned the use of structures such as 1 to couple and decouple amines/thiols in polymers,26 as well as facilitate disulfide dynamic exchange, as two reversible covalent bonding interactions for independent control of polymer morphology. With these reactions in mind, we pursued linear polymers and cross-linked network creation, along with chemically triggered metamorphosis and degradation. The dramatic topological manipulations reported herein and associated changes in physical properties, induced by chemically triggered transformations, represent a promising approach to generate tunable “smart” materials.

Scheme 1. General Schematic of the Coupling–-Decoupling Reactions Exploited Hereina.

aThe addition of an amine to 1 or 3 leads to formation of 2 through thiol release. Next, thiols can be scrambled using structures such as 1 or 2 with varying R-groups. The addition of various reagents releases thiols and amines in aqueous conditions and can create species 4 and the generalized structures 5, 6, and 7, each with distinctive UV–vis λmax values (4: 250 nm, 5: 290 nm, 6: 330–350 nm, and 7: 280–300 nm).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

New Conjugate Acceptor (CA) and Clicking–Declicking Reactions.

The core unit and basis for topological versatility for the polymers and gels was the conjugate acceptor 3, which was synthesized from Meldrum’s acid, carbon disulfide, and 6-iodo-1-hexyne in DMSO at room temperature in an analogous manner to 121,27 (Scheme 2, Figures S1–S3). This subunit was the central, modifiable linker that was used in coupling or cross-linking polymer entities that allowed for amine/thiol scrambling or disulfide exchange to chemically trigger morphological changes of the polymer/gel and subsequently “declick” degradation.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of the Conjugate Acceptor 3

To generate characteristic spectroscopic signals that would allow us to monitor the transformations of the polymers and gels, we analyzed the spectral differences of the chromophores involved in the clicking and declicking reactions of 1 with small molecules via UV–vis spectrophotometry. The vinylogous thio, oxo, and amino derivatives shown in Scheme 1 all have distinct absorbance spectra. For example, the reaction of 3 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with DTT, β-mercaptoethanol (BME), ethanedithiol (EDT), cysteine (Cys), and cysteamine (CYA) gave distinguishable UV–vis absorbance spectra. The λmax for 3 was at 350 nm, while reagent-induced declicking led to blue-shifted spectra and different λmax values depending on the structure of the cyclized products: DTT (250 nm, a tricyclic product, 4),28 BME (290 nm, 5), EDT (330 nm, 6), and Cys or CYA (280 nm, 7) (Figure S4). The relative speed of decoupling was DTT > BME > EDT ~ CYA > Cys. Thus, the chemical group interchanges involved in the polymer/network topological changes could be monitored by simple UV–vis absorbance spectroscopy, and the rate of decoupling could be controlled, if desired. As described below, the λmax values allowed us to follow the extent of chemical functional group interchange.

Next, LC-MS was employed to monitor the reactions between 3 and small molecular amines, such as benzyl amine (8) and 1,3,5-triaminomethylbenzene (9), to confirm the expected monothiol displacements. After 5 min, LC-MS peaks corresponding to complete product formation (10 and 11, CA = conjugate acceptor derived from 3) were identified for both amines (Scheme 3, Figure S5). Further, upon addition of a declicking trigger (DTT), the LC-MS peak corresponding to 10 and 11 vanished and a peak indicative of the tricyclic product 4 was observed (Figure S6), confirming that 3 retained similar chemical properties to 1 in the context of click and declick reactions.

Scheme 3.

Reactions between 3 and Amine Derivatives

Polymer Design, Analysis, and Transformation. An Overview.

To start, we created four polymer types by using standard CuAAC reactions: dimerized PEG 12, linear hydrophobic 13, hyperbranched 14, and cross-linked hydrogel 15 (Schemes 4 and 5). There were several reasons to choose these four architectures as our starting point. Linear polymers such as polyethylene, nylons, and polyesters possess high densities, high tensile strengths, and high melting points.30 Lightly cross-linked polymers have been widely applied in many applications, such as light-emitting materials, biomaterials, and composites.31 Hydrogels are commonly used scaffolds in tissue engineering, drug delivery, and sensing.32,33 Important for our triggered morphology changes, these four starting polymeric architectures contain repeating core conjugate acceptors analogous to 1 and 3. These acceptors could undergo reactions with amine-terminated polymers or branched monomers via the click reaction that releases thiols. In turn, the released thiols can be used in oxidation/reduction reactions through disulfide exchange. Thus, starting with structures 12–15, amphiphilic linear 16, lightly cross-linked homopolymer 17, random copolymer 18, cross-linked polymer 19, and hydrogels 20, 21, and 22 were generated by amine scrambling and disulfide formation (Scheme 4 and Table S1). Furthermore, all the polymeric architectures—before or after morphological changes—were degraded into small molecules or homopolymers induced by declick triggers, hence presaging potential applications such as plastic remediation, drug delivery, tissue engineering, or microelectronics.2,5

Scheme 4. Schematic Representation of the Polymer Synthesis and Topological Changes Achieved via Click–Declick Chemistry and Disulfide–Thiol Scramblinga.

aDimerized PEG (12) and hydrophobic linear polymer (13), lightly cross-linked polymer (14), and hydrogel (15) were synthesized via CuAAC. New amphiphilic linear polymer 16, lightly cross-linked 17, random copolymer 18, cross-linked polymer 19, and hydrogels 20, 21, and 22 were created via amine scrambling using the conjugate acceptor core of 3 and/or thiol–disulfide reactions. Note: Given the potential hazards of poly(azide) compounds, the reactions were carried out in the fume hood, treated carefully, and stored and used in safe places.29

Scheme 5. Synthesis of the Initial Set of Subunitsa.

aReagents and conditions: (a) CuSO4·;5H2O, sodium ascorbate, tert-butanol/H2O = 1:1 (vol), 20 °C; (b) CuI, tris(benzyltriazolylmethyl)amine (TBTA), sodium ascorbate, THF/DMF/H2O = 2:2:1 (vol), 20 °C; (c) CuI, TBTA, sodium ascorbate, THF/DMF/H2O = 1:1:1 (vol), 20 °C; (d) CuSO4·5H2O, sodium ascorbate, tert-butanol/H2O = 1:1 (vol), 20 °C.

Dimerized PEG Transformation to Aggregated Structures.

The dimerized PEG 12 was formed by CuAAC of poly(ethylene glycol) methyl ether azide (23, Mn ca. 1000 g mol−1) and 3 in a tert-butanol/water mixture (Scheme 5). Proton NMR spectroscopy (Figure S7) displayed the formation of triazole moieties, and LC-MS spectra (Figures S8, S9) showed the product with mass/charge ratio (m/z) = 2565.40 for [12 + H]+ and 1327.24 for [12 + 2H]2+. Next, gel permeation chromatography (GPC) displayed a shift to a lower elution time for 12 compared to 23 (Figure 1E), indicating the successful click of 23 with 3.

Figure 1.

UV–vis absorbance time kinetics, GPC, and rheometry for the polymer remodeling. (A) 12 (0.25 mg/mL) to 16 using amine-terminated polystyrene 24 (1.0 mg/mL); (B) 13 (0.4 mg/mL) to 17 using 1,3,5-triaminomethylbenzene (9) (20 μM); (C) 13 (0.2 mg/mL) to 18 using PEG diamine 26 (0.2 mg/mL); (D) 14 (0.14 mg/mL) to 19 using 9 (41 μM) before adding hydrogen peroxide. The time kinetics were run in chloroform every 20 min for (A); every 10 min for (B) and (D); every 30 min for (C); (E) GPC for 12, 16, 23, and 24 in chloroform; (F) DLS for 16 in water; (G) GPC for 13 and 18 in chloroform; (H) GPC for 13 and 17 in DMF (containing 0.01 M LiBr); (I) GPC for lightly cross-linked polymer 14 in chloroform; (J) storage modulus G′ and loss modulus G″ for cross-linked polymer 19; (K) storage modulus G′ and loss modulus G″ for swelled hydrogels 15, 20, 21, and 22 in HEPES buffer.

To transform 12 to an amphiphilic polymer, amine-terminated polystyrene 24 (Mn ca. 5000 g mol−1) was utilized to scramble one thiol of 12 to generate 16 (Scheme 4 and Figure S10). To monitor the transformation, UV–vis absorbance was used, which revealed a blue-shifted ratiometric signal corresponding to product formation. Specifically, the shift in absorbance of the bis-vinylogous thiol ester, as found in structure 1 (as in 6) (λmax = 330–350 nm), relative to an amine/thiol version of the conjugate acceptor, as found in structure 2 (as in 7) (λmax = 310 nm), indicated the formation of polymeric product 16 (Figures 1A and S11). In GPC analysis, 16 displayed a lower retention time and higher molecular weight (Mn = 5800 g mol−1) with Ð = 1.3 (Figure 1E). Subsequently, 16 was investigated using dynamic light scattering (DLS) to evaluate the size and amphiphilic properties (Figures 1F, S12, and S13). The correlation in size determined by DLS in aqueous solution (ca. 90 nm) suggests that 16 existed in assemblies.34–36 Thus, a hydrophilic freely aqueous soluble compound was triggered to generate aggregation in situ by an exchange of a single block unit.

Hydrophobic Polymer Transformations to Lightly Cross-Linked and Amphiphilic Copolymers.

The linear hydrophobic polymer 13 was obtained through step-growth CuAAC polymerization between 3 and 1,4-di(azidomethyl)-benzene (25), which afforded a yellow solid (Mn = 5300 g mol−1, Ð = 1.35) after precipitation and purification. (Scheme 5, Figure S14). Simple addition of 1,3,5-triaminomethylbenzene 9 to 13 resulted in a distinctive change in the polymer backbone as well as cross-linking. UV–vis time-kinetics displayed a blue-shift due to amine scrambling (i.e., analogous of 1 to 2), giving a clean isosbestic point at λ = 325 nm (Figure 1B). 1H NMR spectroscopy titrations of 13 with 9 demonstrated amine-induced scrambling and complete thiol release (Figure S15). This topological change releases dangling thiols in the polymer, and we took advantage of this to further cross-link the material. Thus, oxidation of the dangling thiols to disulfides was performed by addition of H2O2, generating lightly cross-linked polymer 17 (Mn = 21.0 kg mol−1, Ð = 1.18, Figure 1H, Table S2, and Figure S16). In Figure 1H, the prominent shoulders are likely due to smaller molecular weight polymers/oligomers with different extents of cross-linking. The approximate molecular weight of these shoulders is 200 g/mol and lower. To further determine the role of H2O2, we checked if sulfoxides were formed by oxidation of the thioethers on the Meldrum’s acid derivatives. LC-MS was used to monitor the reaction between 1 and H2O2. This was conducted using the same conditions used in creating polymer 17, and there was no chemical reaction (Figure S17). Also, an additional experiment was carried out with an excess of H2O2, and again no reaction was found. All the above data show that polymer 17 was constructed by two covalent attachments, one through the thiol/amine conjugate such as 2 and the other through disulfide bonds. Thus, we triggered both backbone and cross-linking interchanges from a hydrophobic polymer to a lightly cross-linked network.

In the next transformation, poly(ethylene glycol) diamine 26 (Mn = 6000 g mol−1) was used to functionalize 13, again via thiol displacement. Following the reaction between 13 and 26 in 1:1 ratio, product 18 was precipitated from cold methanol. UV–vis spectroscopy again demonstrated a decrease in the absorbance of 350 nm and increase at 310 nm (Figure 1C), while GPC displayed a lower retention time and higher molecular weight (Mn = 38.9 kg mol−1, Ð = 1.39, Table S2) for 18, indicating the formation of longer random copolymers (Figure 1G). Additionally, analysis of the 1H NMR spectrum (Figure S18) revealed the presence of peaks corresponding to PEG backbone protons. These data demonstrate successful chemically triggered remodeling of the linear polymers through amine/thiol scrambling.

Lightly Cross-Linked Polymer Transformations to Cross-Linked Polymer.

Lightly cross-linked polymer 14 was synthesized through the copper-catalyzed click reaction between 3 and 1,3,5-tris(azidomethyl)benzene (27) (Scheme 5, Figure S19). GPC with multiangle light scattering detection gave the molecular weight for 14 (Mn = 14.9 kg mol−1, Ð = 1.16, Figure 1I, Table S2). Using 1H NMR analysis via the method of Moore,37 an approximate degree of branching of 65% was obtained. Similar to the reaction of 12 or 13, UV–vis kinetics of the reaction of 14 with the triamine 9 demonstrated a blue-shift, and new 1H NMR spectroscopy resonances appeared in a time-dependent manner (Figures 1D and S20). The analyses confirmed the remolding of the architecture and the release of thiol moieties.38 The product was directly oxidized with H2O2, resulting in the highly cross-linked polymer 19 in a dimethylformamide (DMF)/tetrahydrofuran (THF) mixture, which exists as a gel (Figure S21). Rheometric tests found the storage modulus (G’) to be an average of 5.5 kPa and the loss modulus (G″) to be 1.5 kPa on average, slightly increasing with the change of angular frequency in the range 0.1–100 rad/s (Figure 1J). In summary, lightly cross-linked polymeric backbones were morphed, resulting in gels in situ by simple addition of a cross-linking unit.

Hydrogel Transformations to Single and Double Networking Hydrogels.

In addition to polymers, the strategies discussed here were applied to hydrogels. Initially, hydrogel 15 was synthesized via click reaction between 3 and four-arm poly(ethylene glycol) azide (28) (Mn ≈ 10.0 kg mol−1) in a water/tert-butanol mixture (Scheme 5). The volume of the hydrogel was expanded after swelling in water due to the hydrophilic network (see Supporting Information), resulting in a frequency-independent storage modulus of 2.2 kPa (Figure 1K).

Next, DTT was used to degrade the hydrogel by cleaving the linkage at conjugate acceptor core 3, leading to the quantitative generation of four-arm PEG thiol 29 (Figure 2E) in pH 7.3 HEPES (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid) buffer. After removal of 4 and residual DTT by dialysis, the resulting system containing numerous free thiols was cross-linked through disulfide bonds by addition of H2O2, generating a new networking matrix: hydrogel 20 (Table S1, Figure S22). Gel 20 demonstrated a softened elastic modulus of only 260 Pa, corresponding to lower overall cross-link density (Figure 1K). Continuing with the theme, we employed four-arm poly(ethylene glycol) amine 30 (Mn ca. 2.0 kg mol−1) to construct hydrogel 21, using multiple amines separated by long PEG chains that expanded the matrix of the hydrogel through scrambling thiols on the conjugate acceptor. Visibly, hydrogel 15 became a viscous liquid after mixing with 30 for 6 h (1:1 ratio to the conjugate acceptor), liberating the thiols along with a noticeable odor. Subsequent addition of H2O2 linked the free thiols as disulfides in a second cross-linking, leading to hydrogel 21 (Figure S23). Rheometric testing gave an even softer storage modulus (75 Pa) for the swelled hydrogel, which supported our proposed role of 30 to expand the hydrogel matrix. Next, four-arm PEG thiol 31 (Mn ca. 5.0 kg mol−1, 1:1 ratio to the conjugate acceptor) was utilized to morph the matrix of hydrogel 15, of which the thiols would exchange between a bis-vinylogous thiol ester in 15 and thiol-terminated derivative 31. Subsequently, released free thiols enabled the second cross-linking through formation of disulfides, generating hydrogel 22 (Figure S24). With this different cross-linking, the storage modulus became 230 Pa. Thus, numerous hydrogels of differing physical properties resulting from backbone alterations were readily created via simple mixing of reagents.

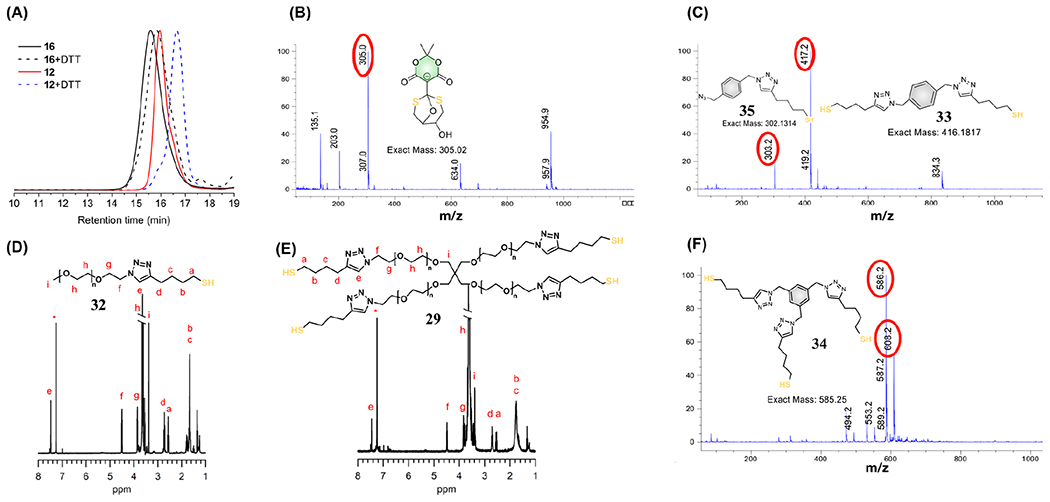

Figure 2.

GPC, 1H NMR spectroscopy, and LC-MS for the polymer degradation. (A) GPC of 12 and 16 before and after degradation; (B) mass spectra for tricyclic product 4 observed in LC-MS; (C) masses for 33 and 35 observed in LC-MS, resulted from decomposition of 13, 17, and 18; (D) 1H NMR for the thiol-terminated PEG product 32 released from 12; (E) 1H NMR for the four-arm PEG thiol 29 degraded from hydrogel 15; (F) mass spectra for 34 released from 14 and 19 in LC-MS.

Significantly, the topological remodeling of the polymer and hydrogel backbones and cross-linkers were performed in neutral aqueous condition at ambient temperature by simply adding new monomers, cross-linkers, polymers, or an oxidant. The resulting spatiotemporal regulation of material properties is promising in the applications of drug delivery systems, cell encapsulation, and cell migration.

Macromolecular Degradation into Small Molecules.

Remodeling and transforming polymeric architectures via chemically triggered synthesis has been described above. Another critical property of a polymer is its ability to degrade, which facilitates controlled removal of plastic pollutants once the material has served its purpose. Further, such triggerable material degradation should hold wide applicability in medicine and drug delivery. As we have stressed throughout, all of the bis-vinylogous thiol esters analogous to 1, bis-vinylogous thiol amine structures containing linkages as in 2, and disulfide bonds could be decoupled by various chemical reagents. Further, with the coexistence of two or more cross-linking chemical bonds, we could control and tune the degradation through different declicking reactions.

First, 12 was treated with DTT in HEPES buffer (pH 7.3) for 3 h, and the solution was then placed in dialysis tubing (1.0 kDa molecular weight cutoff) and suspended in deionized water for 40 h (changing the solvent every 10 h) to remove small molecules (Figure S25). The thiol-terminated product 32 was confirmed by 1H NMR spectroscopy (Figure 2D) and GPC, where a longer retention time (Figure 2A) indicated success of the decoupling reactions. Next, 16 was declicked using DTT for 36 h in HEPES buffer (50% acetonitrile as cosolvent, Figure S26). After dialysis, GPC data showed that the result had a lower molecular weight (Figure 2A). Next, polymers 13, 14, 17, 18, and 19 were all processed in HEPES buffer in the presence of DTT (overnight for 13 and 14; 2 days for 17 and 18; 5 days for 19). As expected, the polymers containing amine/thiol conjugate acceptors, such as structure 2, were more difficult to decompose than the polymers containing thiol ester conjugate acceptors such as with 1, due to the amine being less labile as a leaving group. Yet, all species did entirely degrade with DTT. A macroscopic surface-accessible degradation occurred, which can be seen by the naked eye and analyzed by LC-MS. LC-MS data showed the tricyclic product 4 (Figure 2B), with a mass/charge ratio (m/z) = 305.0 for all polymers declicked by DTT, bis-thiolterminated derivative 33 released from 13, 17, and 18 (m/z = 417.2, Figure 2C, Figures S27–S29), and three-arm thiol derivative 34 released from 14 and 19 (m/z = 586.2, 608.2, Figure 2F, Figures S30 and S31), respectively. We also observed the azide-containing side products 35, 36, and 37 (Figure 2C, Figures S27–S31) from the declick reaction mentioned above, due to an incomplete CuAAC click reaction.

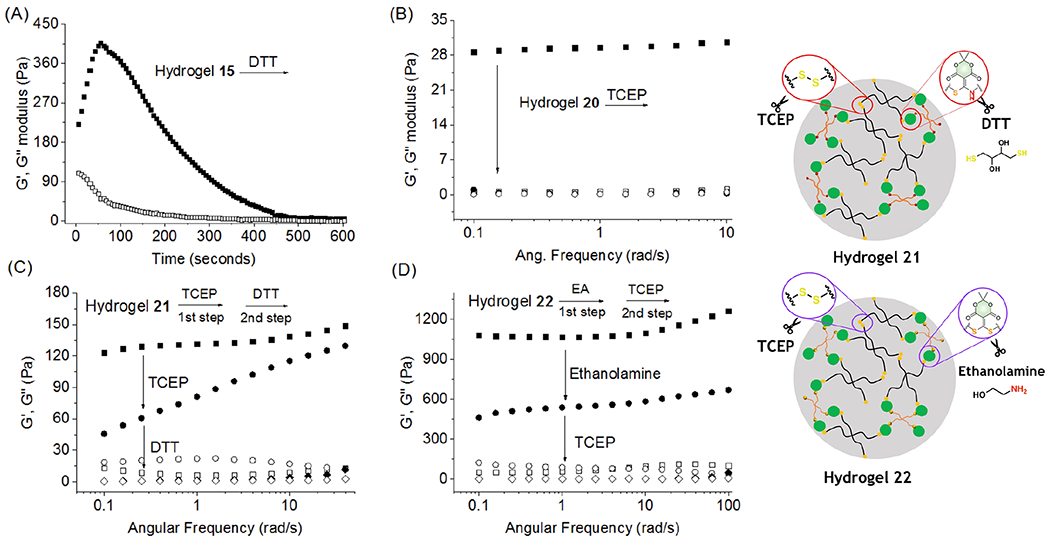

DTT was also successfully used to declick the hydrogels into small molecules. The 3D network 15 was processed in HEPES buffer in the presence of DTT, and after 20 min the yellow gel disassembled, with no disassembly of the control sample without DTT (inset picture in Figure S32). LC-MS verified the generation of 4 (Figure S32), and following dialysis, 1H NMR spectroscopy confirmed formation of 29 (Figure 2E). Furthermore, kinetic studies from the rheometer displayed a decreasing of the storage modulus (G’) due to degradation of hydrogel 15 following addition of DTT, indicating gradual breakage of the matrix (Figure 3A, Figure S33). Next, the viscoelasticity of soft hydrogel 20 (storage modulus G′ = 28 Pa) was transformed rapidly into a solution state (G′ < G″) due to the cleavage of disulfide bonds by tris(2-carboxyethyl)-phosphine (TCEP) (Figure 3B). Following dialysis, the solution state was reversed into a gel under hydrogen peroxide due to the re-formation of disulfide bonds (Figure S34).

Figure 3.

Monitoring hydrogel degradation by a rheometer. (A) Time-based kinetics for degradation of hydrogel 15 in the presence of DTT; (B) TCEP-induced disulfide reduction for hydrogel 20 degradation; (C) two cross-linked networks, a disulfide bond and amine/thiol conjugate acceptor linked in hydrogel 21, were degraded by TCEP and DTT, respectively; (D) two cross-linked networks, a bis-vinylogous thiol ester such as 1 and a disulfide bond linking hydrogel 22, were degraded by ethanolamine and TCEP, respectively. The storage modulus and loss modulus for hydrogels 20, 21, and 22 were scanned before and after degradation.

The cross-linked matrixes 21 and 22 could also be tuned and controlled by different decoupling reagents. The matrix of hydrogel 21 (G’ ≈ 130 Pa), containing both the amine/thiol conjugate and disulfide bonds, was tuned separately by TCEP for the reduction of disulfides (G’ ≈ 70 Pa) and subsequently by DTT for the cleavage of the thiol-amine conjugate analogous to 2 (G’ ≈ 5 Pa, Figures 3C and S35). For hydrogel 22 (G’ ≈ 1000 Pa), ethanolamine was employed to cut off the bis-vinylogous thiol ester core analogous to 1 (G’ ≈ 500 Pa), and then TCEP was used to reduce the disulfide bonds (G’ ≈ 5 Pa), decomposing the cross-linked hydrogel entirely into small molecules (Figures 3D and S36). The tunable and degradable properties of the hydrogels, particularly the ability to tune the two dynamically cross-linked samples under physiological conditions, are potentially applicable in drug delivery systems and tissue bioengineering.

CONCLUSION

We have demonstrated in macromolecular constructs the versatility of being able to click thiols, and amines and thiols, via structures analogous to 1 to make morphable soft materials. By simply controlling the sequence of addition of monomers, cross-linkers, or polymers, we could chemically trigger interconversion of backbone architectures and cross-links, control polymer morphologies, and alter macroscopic properties, all at ambient temperature in aqueous media. Specifically, the reversible conjugate additions inherent in the organic chemistry of 1 and its analogues introduced herein, coupled with thiol–disulfide scrambling, led to very simple approaches that interconvert linear hydrophobic, hydrophilic, and amphiphilic polymers, as well as lightly cross-linked polymers and hydrogels, further even allowing interconversion of random copolymers with other lightly cross-linked polymers. In addition, in a facile fashion four different hydrogels could be created via manipulating the components allowed to react with structures containing the reactivity of 1. The choice of amines and thiols used herein is specific to this study, but clearly the possibilities are vast given the numbers of amine and thiol units that can be imagined. Lastly, and potentially just as important, all the soft materials are degradable with various chemical triggers, although specifically DTT was used in this study. Owing to the mild reaction conditions and ease of use in a wide variety of applications, this method is expected to have numerous material applications.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 6. Schematic Depiction of Polymer Degradation Induced in the Presence of DTT or Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP)/Ethanolamine in Neutral HEPES Buffera.

aThe degradation process was triggered either by the cyclization between a bis-vinylogous derivatives of 3 with DTT, disulfide cleavage by reduction with TCEP, or ethanolamine-induced decoupling of structures such as 1, respectively.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the use of facilities and instrumentation supported by the National Science Foundation through the Center for Dynamics and Control of Materials: an NSF MRSEC under Cooperative Agreement No. DMR-1720595, and NIH grant number 1 S10 OD021508-01. We gratefully acknowledge the support of the Welch Regents Chair (F-0046) to E.V.A. and the Welch Foundation (F-1904) to N.A.L. X.L.S. thanks the National Natural Science Foundation of China for Grant No. 21907080.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.9b12122.

Additional experimental procedures and characterization data, materials and methods, supplementary text, Figures S1 to S36, Tables S1 and S2, captions for data S1 to S36, synthetic preparations (PDF)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/jacs.9b12122

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Xiaolong Sun, The Key Laboratory of Biomedical Information Engineering of Ministry of Education, School of Life Science and Technology, Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’an 710049, People’s Republic of China.

Malgorzata Chwatko, Department of Chemistry/McKetta Department of Chemical Engineering, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas 78712, United States.

Doo-Hee Lee, Department of Chemistry/McKetta Department of Chemical Engineering, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas 78712, United States.

James L. Bachman, Department of Chemistry/McKetta Department of Chemical Engineering, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas 78712, United States

James F. Reuther, Department of Chemistry, University of Massachusetts Lowell, Lowell, Massachusetts 01854, United States.

Nathaniel A. Lynd, Department of Chemistry/McKetta Department of Chemical Engineering, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas 78712, United States.

Eric V. Anslyn, Department of Chemistry/McKetta Department of Chemical Engineering, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas 78712, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Stuart MAC; Huck WT; Genzer J; Müller M; Ober C; Stamm M; Sukhorukov GB; Szleifer I; Tsukruk VV; Urban M Emerging applications of stimuli-responsive polymer materials. Nat. Mater 2010, 9 (2), 101–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Blum AP; Kammeyer JK; Rush AM; Callmann CE; Hahn ME; Gianneschi NC Stimuli-responsive nanomaterials for biomedical applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137 (6), 2140–2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Montero de Espinosa L; Meesorn W; Moatsou D; Weder C Bioinspired Polymer Systems with Stimuli-Responsive Mechanical Properties. Chem. Rev 2017, 117 (20), 12851–12892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Shafranek RT; Millik SC; Smith PT; Lee C-U; Boydston AJ; Nelson A Stimuli-responsive materials in additive manufacturing. Prog. Polym. Sci 2019, 93, 36–67. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Delplace V; Nicolas J Degradable vinyl polymers for biomedical applications. Nat. Chem 2015, 7 (10), 771–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Lamb JB; Willis BL; Fiorenza EA; Couch CS; Howard R; Rader DN; True JD; Kelly LA; Ahmad A; Jompa J Plastic waste associated with disease on coral reefs. Science 2018, 359 (6374), 460–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Christensen PR; Scheuermann AM; Loeffler KE; Helms BA Closed-loop recycling of plastics enabled by dynamic covalent diketoenamine bonds. Nat. Chem 2019, 11 (5), 442–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Su W-F Chemical and Physical Properties of Polymers. In Principles of Polymer Design and Synthesis; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013; pp 61–88. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Scheutz GM; Lessard JJ; Sims MB; Sumerlin BS Adaptable Crosslinks in Polymeric Materials: Resolving the Intersection of Thermoplastics and Thermosets. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141 (41), 16181–16196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Reuther JF; Dahlhauser SD; Anslyn EV Tunable Orthogonal Reversible Covalent (TORC) Bonds: Dynamic Chemical Control over Molecular Assembly. Angew. Chem., Int Ed 2019, 58 (1), 74–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Cudjoe E; Herbert KM; Rowan SJ Strong, Rebondable, Dynamic Cross-Linked Cellulose Nanocrystal Polymer Nanocomposite Adhesives. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10 (36), 30723–30731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Rowan SJ; Cantrill SJ; Cousins GR; Sanders JK; Stoddart JF Dynamic covalent chemistry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2002, 41 (6), 898–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Sun H; Kabb CP; Sims MB; Sumerlin BS Architecture-transformable polymers: Reshaping the future of stimuli-responsive polymers. Prog. Polym. Sci 2019, 89, 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Sun H; Kabb CP; Dai Y; Hill MR; Ghiviriga I; Bapat AP; Sumerlin BS Macromolecular metamorphosis via stimulus-induced transformations of polymer architecture. Nat. Chem 2017, 9, 817–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Kolb HC; Finn M; Sharpless KB Click chemistry: diverse chemical function from a few good reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2001, 40 (11), 2004–2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Kolb HC; Sharpless KB The growing impact of click chemistry on drug discovery. Drug Discovery Today 2003, 8 (24), 1128–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Qin A; Lam JWY; Tang BZ Click polymerization. Chem. Soc. Rev 2010, 39 (7), 2522–2544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Arslan M; Tasdelen MA Click Chemistry in Macromolecular Design: Complex Architectures from Functional Polymers. Chemistry Africa 2019, 2 (2), 195–214. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Binder WH; Sachsenhofer R ‘Click’chemistry in polymer and materials science. Macromol. Rapid Commun 2007, 28 (1), 15–54. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Binder WH; Sachsenhofer R ‘Click’ chemistry in polymer and material science: an update. Macromol. Rapid Commun 2008, 29 (12–13), 952–981. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Diehl KL; Kolesnichenko IV; Robotham SA; Bachman JL; Zhong Y; Brodbelt JS; Anslyn EV Click and chemically triggered declick reactions through reversible amine and thiol coupling via a conjugate acceptor. Nat. Chem 2016, 8 (10), 968–973. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Johnson AM; Anslyn EV Reversible Macrocyclization of Peptides with a Conjugate Acceptor. Org. Lett 2017, 19 (7), 1654–1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Sun X; Anslyn EV An Auto-Inductive Cascade for the Optical Sensing of Thiols in Aqueous Media: Application in the Detection of a VX Nerve Agent Mimic. Angew. Chem 2017, 129 (32), 9650–9654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Sun X; Shabat D; Phillips ST; Anslyn EV Self-propagating amplification reactions for molecular detection and signal amplification: Advantages, pitfalls, and challenges. J. Phys. Org. Chem 2018, 31, e3827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Sun X; Boulgakov AA; Smith LN; Metola P; Marcotte EM; Anslyn EV Photography Coupled with Self-Propagating Chemical Cascades: Differentiation and Quantitation of G- and V-Nerve Agent Mimics via Chromaticity. ACS Cent. Sci 2018, 4 (7), 854–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Ishibashi JSA; Kalow JA Vitrimeric Silicone Elastomers Enabled by Dynamic Meldrum’s Acid-Derived Cross-Links. ACS Macro Lett. 2018, 7 (4), 482–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Ben Cheikh A; Chuche J; Manisse N; Pommelet JC; Netsch KP; Lorencak P; Wentrup C Synthesis of. alpha.-cyano carbonyl compounds by flash vacuum thermolysis of (alkylamino) methylene derivatives of Meldrum’s acid. Evidence for facile 1, 3-shifts of alkylamino and alkylthio groups in imidoylketene intermediates. J. Org. Chem 1991, 56 (3), 970–975. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Meadows MK; Sun X; Kolesnichenko IV; Hinson CM; Johnson KA; Anslyn EV Mechanistic studies of a “Declick” reaction. Chem. Sci 2019, 10 (38), 8817–8824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Bräse S; Banert K Organic Azides: Syntheses and Applications; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Chawla KK; Meyers M Mechanical Behavior of Materials; Prentice Hall, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Zheng Y; Li S; Weng Z; Gao C Hyperbranched polymers: advances from synthesis to applications. Chem. Soc. Rev 2015, 44 (12), 4091–4130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Oliva N; Conde J; Wang K; Artzi N Designing Hydrogels for On-Demand Therapy. Acc. Chem. Res 2017, 50 (4), 669–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Zhu Z; Yang CJ Hydrogel Droplet Microfluidics for High-Throughput Single Molecule/Cell Analysis. Acc. Chem. Res 2017, 50 (1), 22–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Förster S; Antonietti M Amphiphilic block copolymers in structure-controlled nanomaterial hybrids. Adv. Mater 1998, 10 (3), 195–217. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Rösler A; Vandermeulen GW; Klok H-A Advanced drug delivery devices via self-assembly of amphiphilic block copolymers. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev 2001, 53 (1), 95–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Alexandridis P; Lindman B Amphiphilic Block Copolymers: Self-Assembly and Applications; Elsevier, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Markoski L; Thompson J; Moore J Indirect Method for Determining Degree of Branching in Hyperbranched Polymers. Macromolecules 2002, 35 (5), 1599–1603. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Mohapatra H; Phillips ST Using Smell To Triage Samples in Point-of-Care Assays. Angew. Chem., Int Ed 2012, 51 (44), 11145–11148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.