Abstract

Black, Native, and Latinx populations represent the racial and ethnic groups most impacted by poverty. This unequal distribution of poverty must be understood as a consequence of policy decisions - some that have sanctioned violence and others that have created norms - that continue shape who has access to power, resources, rights and protections. In this review, we draw on scholarship from multiple disciplines, including pediatrics, public health, environmental health, epidemiology, social and biomedical science, law, policy, and urban planning to explore the central question—What is the relationship between structural racism, poverty, and pediatric health? We discuss historic and present-day events that are critical to the understanding of poverty in the context of American racism and pediatric health. We challenge conventional paradigms that treat racialized poverty as an inherent part of American society. We put forth a conceptual framework to illustrate how white supremacy and American capitalism drive structural racism and shape the racial distribution of resources and power where children and adolescents live, learn, and play, ultimately contributing to pediatric health inequities. Finally, we offer anti-poverty strategies grounded in anti-racist practices that contend with the compounding, generational impact of racism and poverty on heath to improve child, adolescent, and family health.

Keywords: Structural Racism, Poverty, Capitalism, Pediatric Health

“[T]he association between socioeconomic status and race in the United States has its origins in discrete historical events but persists because of contemporary structural factors that perpetuate those historical injustices. In other words, it is because of institutionalized racism that there is an association between socioeconomic status and race in this country”

-Camara P. Jones, MD, MPH, PhD

Introduction

The field of Pediatrics, which encompasses the health of infants, children, adolescents, and families, has long prioritized addressing poverty. However, our traditional approaches in addressing poverty have neglected the role of structural racism as a root cause of poverty and a key driver of pediatric health inequities.1,2 These approaches fail to attend to the broader structural drivers that impoverish individuals, neighborhoods, and populations. In so doing, our field has ignored the critical role of structural racism thus normalizing the racial distribution of child poverty and, thereby distancing ourselves from effective anti-poverty strategies. In this review, we evaluate the relationship between structural racism, poverty, and adverse pediatric health, briefly exploring historical, anti-poverty legislative efforts and contextualizing the racial/ethnic distribution of poverty. We summarize these findings (Box 1) and present a conceptual framework to illustrate these intersections and organize our discussion into domains according to where children and adolescents live, work, and play (Figure 1). Finally, we offer recommendations for strategies at the nexus of anti-racist and anti-poverty action.

Box 1. Intersections between Structural Racism and Poverty by Social Determinant of Health Domain.

| Domain | Summary |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Live | A child’s physical residence and household may be impacted by the structural forces of racism through: • Lower Homeownership, Predatory lending and Land devaluation • Mass incarceration • Redlining & Gentrification • Wealth gap |

| Learn | An educational “home” is comprised of the physical or built environment, the social environment, and the disposable resources. Schools attended by REM are more likely to have: • Environmental risks (e.g., air, water, and noise pollution) • Lower school funding due to the inequitable allocation (e.g., use of local income tax base) |

| Play | Appropriate play and recreational spaces are critical for children and may promote resilience. However, REM may not experience the health and psychosocial benefits of green spaces due to: • Underexposure to park spaces due to historical atrocities • Poor park quality |

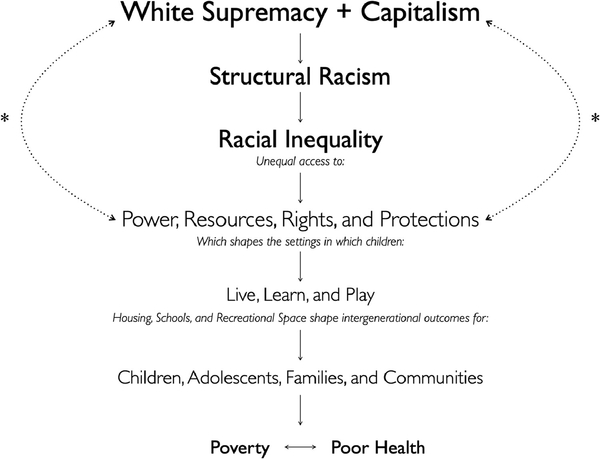

Figure 1.

Structural racism is a product of white supremacy and capitalism. Structural racism is defined as “differential access to societal goods, services, and opportunities by race” and it manifests in unequal access to power, resources, rights, and protections. Racial inequality fundamentally shapes the settings in which children live, learn, and play, and in turn, shapes intergenerational health outcomes at the individual, family, and community level. Together, structural racism, white supremacy, and capitalism create poverty and poor health, and concentrate poverty and poor health among racial and ethnic minorities. * Unequal access to power, resources, rights, and protections by race, reinforces notions of white racial dominance (white supremacy) and racial subjugation provides the social hierarchy that capitalism requires and exploits for profit accumulation.

The Unequal Racial Distribution of Child Poverty

Structural racism binds socioeconomic status to race/ethnicity. Structural racism is a system which confers differential access to societal goods, services, and opportunities by race3 and it shapes and is shaped by white supremacy and capitalism. White supremacy is inclusive of racial hate groups but goes beyond this singularity. Specifically, white supremacy refers to the control of social, cultural, economic, and political power and resources by white people and in their interest.4,5 This control results in and is maintained by the explicit hierarchical ordering of racial groups and the inequitable distribution of resources across racial groups, which justifies and enforces the ideology of whites as the superior or dominant racial group. In the US, white supremacy has been historically upheld by laws, policies, violence, or deprivation.5 These approaches work to disenfranchise racially minoritized (RM)6 groups, and limit their access to resources, power (i.e., social, political, economic, and ideological control), or protections.7,8

Structural racism is also inextricably intertwined with capitalism, the US economic system; however, it is not unique to the American condition. Capitalism requires, maintains, and reinforces the racial hierarchies that structural racism and white supremacy are used to establish. This produces and reproduces racial inequality for profit and allows racial subjugation to both generate capital (e.g., the Transatlantic Slave Trade) and enable capital accumulation (e.g., the racial wealth gap). This historically has occurred through forms of extraction, dispossession, theft, exploitation and through the “free market,” which is predicated on distinct structural advantages (social power, rights, privileges) for certain racial and class groups. Some refer to this interrelationship between racism and capitalism, as “Racial Capitalism.” 9–11

For the purposes of this review, it is beyond the scope to provide the full history of Racial Capitalism, as an analytic for understanding child poverty. But we present it here to be clear that the racial distribution of child poverty in the US, the concentration of poverty within Black, Native, and Latinx populations, and the consequent racial health inequities that result from racial inequality are all a direct product of the relationships between structural racism, white supremacy, and capitalism.12

Together, structural racism, white supremacy, and capitalism function to extract and distribute resources along a racial hierarchy which then concentrates and perpetuates poverty within certain racial groups. The unequal racial distribution of poverty, then, must be understood as the consequence of historic and current profit-incentives like those that devalue RM groups’ assets (e.g., homes and neighborhoods) or their lives and livelihoods (e.g., incarceration, education quality, and employment access). Due to the complexity of these relationships, our conceptual framework illustrates these intersections. This framework is anchored within the social determinants of health (SDoH) model that conceptualizes children’s health as an amalgamation of the exposures that occur within multiple settings (Figure 1).

A Brief History of Federal Anti-Poverty Efforts

Federal efforts to eliminate child poverty have been underway since the early 1900s, with the creation of a Children’s Bureau and the Towner Maternity and Infancy Act, the first national and social program for women and children. However, the 1960s marked a transformational time in US anti-poverty legislation. The Economic Opportunity Act (EOA), informally known as the “War on Poverty,” was a multi-tiered effort that, along with subsequent legislation (Box 2) focused on individual economic uplift but left structural racism unaddressed.13

Box 2. Legislation Passed Adjacent to Economic Opportunity Act by Domain and Purpose.

| Legislation | Domain | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Civil Rights Act (1964) 1 | Civil Rights | Expand access and opportunities for Black Americans (e.g., Desegregated schools; Enhanced Voting Rights Act protections; and Prohibited discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or nationality) |

| Food Stamp Act (1964) 2 | Food | Improve nutrition among low-income households |

| Amendments to the Social Security Act (1965) | General Health & Welfare | Established Medicare and Medicaid |

| Housing and Urban Development Act (1965) 4 | Housing | Created the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), as a cabinet agency and made privately owned housing available to low-income families |

| Elementary and Secondary Education Act, Higher Education Act (1965) 5 | Education | Funded primary and secondary education, |

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 (PL 88-352) (1964)

The Food Stamp Act of 1964 (PL 88-525, 78 Stat. 703) (1964)

The Social Security Amendments of 1965 (PL 89-97, 79 Stat. 286) (1965)

The Housing and Urban Development Act of 1965 (P.L. 89-117, 79 Stat. 451) (1965)

The Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 (P.L. 89-10, 79 Stat. 27) (1965)

The EOA's safety-net programs lowered national poverty levels, but not equally for all racial groups,14 as this legislation was not paired with the enforcement of anti-discrimination regulations. Consequently, while some benefited from these programs, others did not. Specifically, prior to the mid-1960s, 40% of Black Americans lived in poverty and then 30% by the mid-1970s, but the poverty rate never fell as low as 8%, the poverty rate held by white Americans during that time. This uneven racial and ethnic distribution of poverty, and the inequity in adverse health outcomes that accompany it, persists today.14–17

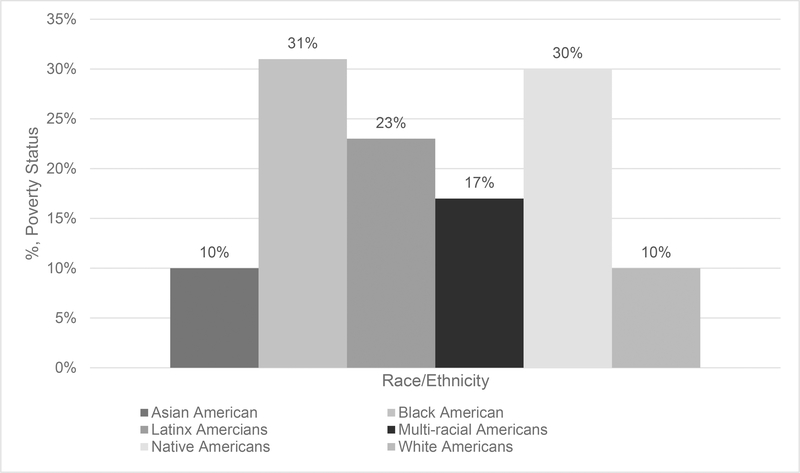

Despite these laudable historical efforts, poverty has proven an indomitable problem. Currently, thirty-four million people (10.5%) and over 10 million children and adolescents under age 18 (14.4%) live below the federal poverty line in the United States.14 While children and adolescents as a whole are the “most likely Americans” to live in poverty; RM youth under 18 disproportionately live below the poverty line and are more likely to live in neighborhoods with concentrated poverty, despite the passage of the EOA (Fig 2).13–15,17 Further, RM individuals who identify as sexual and gender minorities (SGM) face an even higher prevalence of poverty and housing instability than their non-SGM peers.15

Figure 2.

Children and Adolescents in Poverty by Race and Ethnicity, 2019

To understand both the persistence of poverty and its concentration among RM groups, it is critical to explore the historical and contemporary policies and practices, which impacted housing, incarceration, education, and recreational spaces, which imposed structural barriers on families and harmed RM groups, in particular. Thus, preventing RM groups from successfully escaping poverty and in turn, shaping the health of RM children and adolescents uniquely. These structural barriers are best illustrated within the settings where children and adolescents live, learn, and play. Of note, American Indian/Indigenous populations are an important RM population impacted by structural racism, historical trauma, and poverty. Bell et al. more fully addressed the impact of poverty and health within American Indian/Indigenous groups.

Live: The Unequal Distribution of Homeownership and Incarceration

Homeownership provides a significant pathway to social and economic mobility,18 through wealth accumulation and stable housing. However, homeownership has been elusive to many US-based RM groups, particularly Black Americans. Current estimates report homeownership rates at 73% among white Americans, 57.7% among Asian or Pacific Islander Americans, 50.8% among American Indians/Alaskan Natives, 47.5% among Latinx Americans, and 42.1% among Black Americans.19,20 This racial distribution of homeownership reflects a history of discrimination, exclusion, predatory inclusion,21 and economic marginalization perhaps best illustrated by reviewing the impacts of redlining, the Great Recession, and gentrification.

Redlining

Redlining is a form of structural racism and has been described as a “state-sanctioned system of segregation”22,23 Redlining was adopted in the early 1930s through late 1970s by the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) (a federal agency), to advise mortgage lenders as to which neighborhoods were considered lending risks. Geographical areas with higher densities of “undesirable” populations (e.g. Black, Latinx, and Jewish people, low-income whites, immigrants, noncitizens, and communists) were considered risky and outlined in yellow and red on maps, with red areas nearly exclusively reserved for predominantly Black neighborhoods.24 The practice codified white supremacy, enabling white Americans of all economic backgrounds to benefit from more advantaged neighborhoods and higher home values, and justified false racist perceptions that Black Americans lowered housing values. Redlining was used throughout the country25 and reinforced residential segregation originating under slavery, Jim Crow laws and Black codes. Redlining was coupled with higher mortgage interest rates and restrictive housing covenants that limited the housing stock available to Black homeowners, government subsidies that financed white American’s exclusive access to suburbs, and violence that ensued after Black homeowners moved into white neighborhoods. Consequently, Black Americans paid more for substandard housing than white Americans - due to their limited housing options and lack of power within the real estate industry - and were predominantly relegated to urban centers and housing projects.22,23

Redlining also contributed to the seismic wealth gap between racial and ethnic groups in the US. Home ownership encompasses nearly 30% of American families’ wealth.26 Given the exclusion of Black Americans from owning homes and the predatory practices targeted towards those who owned homes, it is unsurprising that Black American household wealth is estimated at 4% of the total US household wealth.27 This absence of wealth further excludes Black Americans from the housing market today and from the indirect benefits of home equity, including affording higher education and intergenerational wealth transfers.28 This creates a generational and cyclical nature to poverty, such that 50% of Black Americans live in the poorest neighborhoods for at least two generations, contrasted to just 7% of white Americans.29

Redlining also fueled neighborhood divestment creating food, healthcare, and “opportunity” deserts, making poorer families less upwardly mobile. The impact of redlining goes beyond economic wellbeing, including present-day impacts on perinatal health. The prevalence of infants small-for-gestational age, perinatal mortality, and preterm births are higher in formerly redlined areas (with higher rates seen in the worst HOLC graded neighborhoods).30–32

The Great Recession

As the housing market boomed in the early 2000s, and the pool of mortgagers and refinancers became smaller, banks targeted individuals with low credit scores, low-income individuals, and RM groups through subprime mortgages. The banks charged expensive fees and rates that outpaced a borrower’s repayment ability. This economic exploitation resulted in increased foreclosures nationally and lead to the collapse of banks and the economy, referred to as “The Great Recession.” Individuals experienced losses of jobs, businesses, and housing, as homeownership became a source of insurmountable debt for families.33 RM groups experienced disproportionate housing and job loss. The Great Recession impacted the construction and manufacturing job market, which had a higher representation of RM groups.24,25 At its peak, the US unemployment rate was 10% overall (October 2009), 15% and 12% for Black Americans and Latinx individuals, respectively. 33,34

Poverty rates during the Great Recession were the highest among Black Americans and Latinx Americans at 26% and 25%, respectively, followed by Asian Americans at 13% and white Americans at 9%. The poverty rates were even higher for youth in 2010. All youth had a poverty rate of 22%, whereas 39% of Black youth and 35% of Latinx youth were in poverty.35 Like redlining, the Great Recession influenced health, as indicated by lower birth rates and higher levels of psychological distress, suicide, and worse subsequent physical health in adults.34 Children also experienced increased adverse health conditions during the period of the Great Recession,, including decreased birthweights and increased prevalence of overweight and obese status in childhood.34 RM youth who experienced more economic hardship during the Great Recession experienced higher levels of epigenetic aging, allostatic load, and worse self-rated health, further demonstrating the relationship between racism, capitalism, poverty, and pediatric health.36

Gentrification

Gentrification refers to an influx of individuals from a favorable social position (i.e., “gentry”) into lower-income neighborhoods. This is often tied to historical patterns of residential segregation and government policies that catalyze gentrification by directing capital and public subsidies into communities unevenly.37 Gentrification prices out long-term residents; displacing them and disrupting social networks. Gentrification may be negatively associated with poor mental health in children but may not influence physical health, like asthma or obesity.38 Thus while housing security, namely homeownership is rarely thought of as an anti-poverty measure; in the US, it is both an anti-poverty and anti-structural racism measure, and vital to improving health equity.

Mass Incarceration

The 1960s “War on Poverty” was also accompanied by a concurrent “War on Crime” that criminalized Black poverty in particular, linked social service support with forms of police surveillance. This ultimately contributed to the expansion of the carceral state and the mass incarceration of RM groups, especially Black Americans.39 Then, the “War on Drugs,” in the 1980s-1990s, led to the racial profiling and targeting of RM groups through excessive arrest, sentencing, and incarceration for drug offenses.39,40 The disproportionate rates of arrests and incarceration were not explained by differences in the use or sale of drugs but rather, policies that instituted severe penalties with the use of certain drugs (e.g., crack cocaine) and mandatory minimum sentencing.40,41 Such practices continue today and influence poverty rates, particularly among Black males. However, the surge in incarceration in the US across racial groups, increased poverty rates that otherwise would have decreased by 20% between 1980–2004.39,42 While incarceration specifically impacts the incarcerated individual, the reach extends to the child and family. Today, mass incarceration impacts over 5 million children and disproportionately impacts low income and rural children, Black and Latinx children.43,44 The incarceration of a parent is associated with juvenile and subsequent involvement in the carceral system.44–46 The experience of both parental incarceration and juvenile justice involvement is associated with depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).44,47,48 Those individuals with a history of parental incarceration in childhood are more likely to skip needed medical care, abuse prescription drugs, and have increased lifetime sexual partners in young adulthood.44 Mass incarceration, which differentially impacts RM groups, due to racial profiling and differential sentencing removes caregivers from the home, potentially disrupting caregiver attachment, and influencing health for multiple generations.

Learn: The Unequal Distribution of Quality Education

The allocation of a school’s resources varies by state and draws from the local income and tax base (20–50%) and state funding (40–70%).49,50 Schools within poorer and majority-minority neighborhoods have a lower tax base and therefore, less resources to provide a quality education because these communities have lower property values and household incomes.24 In essence, residential segregation drives school segregation and under-resourced schools, which often serve the most impoverished communities,51 imperiling educational attainment and making social mobility less attainable. Though student academic achievement is lower in high-poverty RM and non-RM communities alike, Black students report lower academic achievement regardless of poverty status compared to white students.52 This reinforces that additional factors sabotage academic success for RM students,52 impacting health long-term.

School Environment

Though school environments are not defined by their available resources, they may be constrained by them. A school’s environment includes physical/material and social resources. School funding shapes environmental risks (e.g., air and noise quality, water safety, lead exposure, as well as school and playground design) and there is little federal oversight of school environments.49,53–55 Schools with larger concentrations of RM students may be endure more environmental risks and thus present environmental justice concerns.54,55 Schools with substandard physical conditions are associated with adverse health, such as respiratory illness (e.g., asthma53) and lower levels of physical activity, as well as poor school performance49).

However, schools that demonstrate positive sociocultural attributes may be instrumental in supporting children from less resourced environments, narrowing health inequities.50 Key “school determinants” are not only the physical and structural environments, but also include health policies, programs and resources, school climate and composition.50 For example, schools with health programs and professionals (e.g. nurses, counselors, psychologists, or social workers) have positive influences on both physical and mental child health. Similarly, school that promote a positive school climate56 and have a smaller size have benefits including improved mental and behavioral health, substance use, and psychosocial wellbeing.50 Positive school environments may be able to mitigate the relationship between poverty, racism, and health outcomes.

Play: The Unequal Distribution of Recreational Spaces

There is a growing recognition that access to recreational spaces, like national and urban parks, is inequitable. Like housing and schools, high quality green spaces are concentrated in predominately white and affluent areas. When available, green spaces tend to be underutilized by RM groups. This underuse may stem from historic place-based discrimination.57 Prior to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, many RM groups were legally prohibited from using national and state parks or forced to use segregated facilities, and attempts to integrate these spaces would result in violence.57,58 Thus, for some RM groups, some green spaces represent “sick places” and may serve as painful reminders of sites of torture or death.57 The historic and violent exclusion of previous generations of RM groups may have led to underexposure for subsequent generations that persists today.

A more contemporary barrier to park use may be park quality, and its connection to park funding, which is driven by competitive philanthropic grants or national funds. In essence, park funding relies largely on a volunteer workforce comprised of grant writers.59 Cities with higher median incomes and less Black and Latinx residents have higher quality parks. Predominately Latinx cities experienced more park inequities than Black cities.59 Other structural barriers that keep RM groups out of green spaces include socioeconomic resources, transportation, knowledge of outdoor activities, safety concerns, and a white workforce dressed similarly to law enforcement.57,58,60,61

Green Spaces & Health

The relationship between green spaces and positive child health outcomes has been established.62 However, impoverished, non-urban, and RM youth are less likely to have a neighborhood park.63 Children without a neighborhood park are less physically active, spend more time on screens, and experience worse sleep.63 Further, lack of parks are associated with higher BMI and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder diagnosis.63,64 Conversely, access to green spaces is associated with lower emotional and behavioral conditions and may be beneficial to mental well-being in youth but these findings are mixed.63,65 However, poor children, non-urban children, and RM children may be less likely to benefit from the health benefits of green spaces due their absence and underuse. Given the influence of redlining and residential segregation, environment justice concerns extend beyond the presence of green space. These include the of the lack of clean air and water, as well as the lack of greenery and shade in areas with higher concentrations of RM populations.65,66 These environmental exposures are tied to behavioral and cognitive health.67

Discussion

This review illustrates the how structural racism, white supremacy, and capitalism limit access to material resources, like housing, education, and recreational spaces, independent of income. Historical factors such as redlining, school segregation and inequitable access to education and opportunities, as well as contemporary factors, like mass incarceration, recessions, gentrification, school quality, and green space access, are all critical to discussions of child poverty. Using the frame of structural racism, we can better account for and ameliorate the disproportionate rates of poverty among RM groups.

Policy initiatives like raising the minimum wage or expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit have been proposed to lower poverty rates.68,69 However, they do little to address the opportunity gaps that create barriers to employment, the racial wealth gap that creates barriers to mobility, and differential access to healthcare and other resources. Enduring solutions to undo the harmful influence of poverty on child and adolescent health must confront structural racism and white supremacy which exploit racial subjugation for profit accumulation. These solutions will be multi-level, complex, and require partnerships between communities, academic, government, and private sectors. Effective anti-poverty solutions must also account for privilege and power inequality and seek to redistribute power and resources through policies such as: reparations, decarceration, and equitable educational and recreational funding.

Reparations.

Financial renumeration for the transatlantic slave trade, must be understood as a foundational anti-racist, anti-poverty measure. Without such wealth redistribution that both acknowledges and accounts for American capitalism as a structural driver of child poverty and poor health outcomes, the unequal racial distribution of child poverty will persist.70 While debate remains regarding the mechanism of such reparations, plans should be made for the US government and every private institution that benefitted from slavery and land dispossession and theft to publicly acknowledge, atone for, and redress such harms. And although some American Indian/Indigenous tribes entered into charters with the US government to account for these losses, ongoing threats to American Indian/Indigenous sovereignty underscore the importance of articulating reparative processes for these tribes as well. Reparations would allow descendants of the enslaved to buy homes, start businesses, pay for educational expenses, as well as build and transfer wealth, narrowing pediatric health inequities for future generations.

Decarceration with support.

Over-policing, racial profiling in arrests and sentencing, as well as mandatory minimums and other disparate sentencing practices have contributed to the disproportionate incarceration of RM groups, namely Black men, fracturing families.71 Transnational efforts for criminal justice reform are underway,72 and mostly targeted the twenty percent of persons incarcerated for nonviolent or drug offenses.73 However, decarceration efforts should be expanded to include incarcerated persons as a whole. There is substantial evidence that structural racism is embedded within the carceral system from lawmaking to sentencing, release or capital punishment decisions.71 Additionally, 555,000 individuals are held in jails awaiting trials because they are unable to post bail, and nearly 70% are RM groups.73,74 Further highlighting the links between racism and poverty.

Importantly, decarceration necessitates wraparound services for those re-entering communities. Educational and job resources, housing support, and access to health care, mental health, and substance programs will help to combat the disenfranchisement of formerly incarcerated individuals. In essence, the conditions that likely contributed to incarceration will need to be remedied. Decarceration along with other criminal justice reform efforts would impact formerly incarcerated individuals, but also serve as a primary prevention strategy for adverse physical and mental health among their children.

Equitable Educational and Recreational Funding and Spaces.

Schools that have higher needs are often in under-resourced communities without appropriate funding, staffing, and community support which may further health inequities.71 To address the innumerable challenges faced by students and schools in economically distressed neighborhoods, school funding and resource allocation require radical changes. The amount of funding schools receive from their district and state should be inversely proportional to the tax base supporting that school. Creating programs in high-needs schools that attract and retain high-quality teachers and have health-professionals and services available will better meet student needs. Similarly, recreational spaces, should have equitable funding and quality, and not rely on the presence of competitive grant-writers and environmental justice advocates. High quality recreational spaces in RM communities are needed to support the socioemotional development of children, promote thriving, and positive health outcome for children.

Conclusion

The US is experiencing a sociopolitical and racial re-birth that necessitates acknowledging and undoing racist policies and practices. Pediatrics must attend to structural racism within our clinical, research, education, and advocacy efforts.75 Specifically, this focus requires the confrontation of white supremacy and capitalism as drivers of racism, poverty, and other SDoH. Child health advocates must engage multidisciplinary partners to better address the historic and contemporary processes that link structural racism and poverty to pediatric health. Eliminating racism and white supremacy will uncouple the link between race and poverty and is required to eradicate poverty and eliminate racial health inequities.

What this narrative review adds.

This narrative review article integrates multidisciplinary scholarship to illustrate the relationship between racism, poverty, and pediatric health in the United States. We discuss the impact of historic and present-day legislation on poverty and provides suggestions for future policy efforts.

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to offer our sincere thanks to Wayne Garris, JD, MAPP, and Drs. Edith Chen and Diane Whitmore Schanzenback, who critically edited this manuscript, and toto Peggy Murphy, the research librarian who helped to identify articles for this manuscript. Finally, we acknowledge those who have been made impoverished and minoritized due to a persistent but changeable structure.

Funding:

N. Heard-Garris’s efforts was supported by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (5K01HL147995-02) and K. Kan’s efforts were supported by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K12 HS026385-01). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agency.

Sources:

Income and Poverty in the United States: 2019. The United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2020/demo/p60-270.html. Accessed October 29, 2020.

Selected Population Profile in the United States. American Community Survey. Table ID: 20201. Published 2019. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=ACSSPP1Y2017.S0201&t=006%20-%20American%20Indian%20and%20Alaska%20Native%20alone%20%28300,%20A01-Z99%29&tid=ACSSPP1Y2019.S0201. Accessed October 30, 2020.

Financial Disclosure: None of the authors have any financial relationships relevant to the work presented.

Conflict of Interest: None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Neckerman KM, Garfinkel I, Teitler JO, Waldfogel J, Wimer C. Beyond Income Poverty: Measuring Disadvantage in Terms of Material Hardship and Health. Academic Pediatrics. 2016;16(3):S52–S59. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Short KS. Child Poverty: Definition and Measurement. Academic Pediatrics. 2016;16(3):S46–S51. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2015.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(8):1212–1215. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.8.1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ansley FL. White Supremacy (and What We Should Do about It). In: Delgado R, Stefancic J, Eds. Critical White Studies: Looking Behind the Mirror. Temple University Press; 1997. Accessed March 3, 2021. https://search.library.northwestern.edu [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyd RW. The case for desegregation. Lancet. 2019;393(10190):2484–2485. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31353-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stewart D-L. Racially Minoritized Students at U.S. Four-Year Institutions. The Journal of Negro Education. 2013;82(2):184–197. doi: 10.7709/jnegroeducation.82.2.0184 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grabb EG. Theories of Social Inequality - Classical and Contemporary Perspectives. Third Edition. Harcourt Canada; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poland B, Lehoux P, Holmes D, Andrews G. How place matters: unpacking technology and power in health and social care. Health Soc Care Community. 2005;13(2):170–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2005.00545.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robinson CJ, Kelley RDG. Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. 2nd edition. University of North Carolina Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leroy J, Jenkins D, eds. Histories of Racial Capitalism. Columbia University Press; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelley RDG. What Did Cedric Robinson Mean by Racial Capitalism? Boston Review. Published January 12, 2017. Accessed May 14, 2021. http://bostonreview.net/race/robin-d-g-kelley-what-did-cedric-robinson-mean-racial-capitalism [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laster Pirtle WN. Racial Capitalism: A Fundamental Cause of Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic Inequities in the United States. Health Educ Behav. 2020;47(4):504–508. doi: 10.1177/1090198120922942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Children in poverty by race and ethnicity | KIDS COUNT Data Center. Accessed November 12, 2020. https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/44-children-in-poverty-by-race-and-ethnicity

- 14.Selected Population Profile in the United States. Amercian Community Survey. Table ID: 20201. Published 2019. Accessed October 30, 2020. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=ACSSPP1Y2017.S0201&t=006%20-%20American%20Indian%20and%20Alaska%20Native%20alone%20%28300,%20A01-Z99%29&tid=ACSSPP1Y2019.S0201 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Badgett MVL, Choi SK, Wilson BDM. LGBT Poverty in the United States: A Study of Differences between Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Groups. UCLA School of Law Williams Institute; 2019:47. Accessed October 19, 2020. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/National-LGBT-Poverty-Oct-2019.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaudry A, Wimer C. Poverty is Not Just an Indicator: The Relationship Between Income, Poverty, and Child Well-Being. Academic Pediatrics. 2016;16(3):S23–S29. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2015.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bureau UC. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2019. The United States Census Bureau. Accessed October 29, 2020. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2020/demo/p60-270.html [Google Scholar]

- 18.Millstein E. Beneficial impacts of homeownership: A research summary. Published online 2016. Accessed October 19, 2020. http://www.habitatbuilds.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Benefits-of-Homeownership-Research-Summary.pdf

- 19.Quarterly Homeownership Rates by Race and Ethnicity of Householder for the United States: 1994–2019. Figure 8. US Census. Accessed October 30, 2020. https://www.census.gov/housing/hvs/data/charts/fig08.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 20.US homeownership rates by race. USAFacts. Accessed October 25, 2020. https://usafacts.org/articles/homeownership-rates-by-race/

- 21.Taylor K-Y. Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership. The University of North Carolina Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rothstein R. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. Reprint Edition. Liveright; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23.A “Forgotten History” Of How The U.S. Government Segregated America. NPR.org. Accessed October 20, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2017/05/03/526655831/a-forgotten-history-of-how-the-u-s-government-segregated-america

- 24.Harshbarger AMP and D. America’s formerly redlined neighborhoods have changed, and so must solutions to rectify them. Brookings. Published October 14, 2019. Accessed October 20, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/research/americas-formerly-redlines-areas-changed-so-must-solutions/ [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson R, Madron J, Ayers N. Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America. Accessed October 20, 2020. https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/

- 26.Eggleston J, Hays D, Munk R, Sullivan B. The Wealth of Households: 2017. United States Census Bureau; 2020:6. Accessed October 27, 2020. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2020/demo/p70br-170.html [Google Scholar]

- 27.Broady EM, McIntosh Kriston, Edelberg Wendy, and Kristen E. The Black-white wealth gap left Black households more vulnerable. Brookings. Published December 8, 2020. Accessed February 4, 2021. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/12/08/the-black-white-wealth-gap-left-black-households-more-vulnerable/ [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chaudry A, Wimer C, Macartney S, et al. Poverty in the United States: 50-Year Trends and Safety Net Impacts. Office of Human Services Policy Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2016:47. Accessed October 19, 2020. https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/154286/50YearTrends.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 29.Massey DS, Tannen J. A Research Note on Trends in Black Hypersegregation. Demography. 2015;52(3):1025–1034. doi: 10.1007/s13524-015-0381-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matoba N, Suprenant S, Rankin K, Yu H, Collins JW. Mortgage discrimination and preterm birth among African American women: An exploratory study. Health Place. 2019;59:102193. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krieger N, Van Wye G, Huynh M, et al. Structural Racism, Historical Redlining, and Risk of Preterm Birth in New York City, 2013–2017. American journal of public health. 2020;110(7):1046–1053. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2020.305656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nardone A, Casey JA, Morello-Frosch R, Mujahid M, Balmes JR, Thakur N. Associations between historical residential redlining and current age-adjusted rates of emergency department visits due to asthma across eight cities in California: an ecological study. Lancet Planet Health. 2020;4(1):e24–e31. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(19)30241-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.What Really Caused the Great Recession? Institute for Research on Labor and Employment. Published September 19, 2018. Accessed October 28, 2020. https://irle.berkeley.edu/what-really-caused-the-great-recession/ [Google Scholar]

- 34.Margerison-Zilko C, Goldman-Mellor S, Falconi A, Downing J. Health Impacts of the Great Recession: A Critical Review. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2016;3(1):81–91. doi: 10.1007/s40471-016-0068-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.A lost decade: Poverty and income trends continue to paint a bleak picture for working families. Economic Policy Institute. Accessed October 17, 2020. https://www.epi.org/publication/lost-decade-poverty-income-trends-continue/ [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen E, Miller GE, Yu T, Brody GH. The Great Recession and health risks in African American youth. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2016;53:234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zuk M, Bierbaum AH, Chapple K, Gorska K, Loukaitou-Sideris A. Gentrification, Displacement, and the Role of Public Investment. Journal of Planning Literature. 2018;33(1):31–44. doi: 10.1177/0885412217716439 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dragan KL, Ellen IG, Glied SA. Gentrification And The Health Of Low-Income Children In New York City. Health Affairs. 2019;38(9):1425–1432. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haveman R, Blank R, Moffitt R, Smeeding T, Wallace G. The War on Poverty: Measurement, Trends, and Policy. J Policy Anal Manage. 2015;34(3):593–638. doi: 10.1002/pam.21846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mitchell O. Is the War on Drugs Racially Biased? Journal of Crime and Justice. 2009;32(2):49–75. doi: 10.1080/0735648X.2009.9721270 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drugs and Narcotics - Crack Cocaine, Race, And The War On Drugs. Accessed November 16, 2020. https://law.jrank.org/pages/6299/Drugs-Narcotics-CRACK-COCAINE-RACE-WAR-ON-DRUGS.html

- 42.DeFina R, Hannon L. The Impact of Mass Incarceration on Poverty. Crime & Delinquency. 2013;59(4):562–586. doi: 10.1177/0011128708328864 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murphey D, Cooper P. Parents behind bars: What happens to their children? Child Trends. Published October 2015. Accessed November 2, 2017. https://www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/2015-42ParentsBehindBars.pdf

- 44.Heard-Garris N, Winkelman TNA, Choi H, et al. Health Care Use and Health Behaviors Among Young Adults With History of Parental Incarceration. Pediatrics. 2018;142(3). doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kopak AM, Smith-Ruiz D. Criminal Justice Involvement, Drug Use, and Depression Among African American Children of Incarcerated Parents. Race and Justice. 2016;6(2):89–116. doi: 10.1177/2153368715586633 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roettger ME, Swisher RR. Associations of Fathers’ History of Incarceration with Sons’ Delinquency and Arrest Among Black, White, and Hispanic Males in the United States*. Criminology. 2011;49(4):1109–1147. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2011.00253.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heard-Garris N, Sacotte KA, Winkelman TNA, et al. Association of Childhood History of Parental Incarceration and Juvenile Justice Involvement With Mental Health in Early Adulthood. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(9):e1910465. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee RD, Fang X, Luo F. The impact of parental incarceration on the physical and mental health of young adults. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):e1188–1195. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sampson N. Environmental justice at school: understanding research, policy, and practice to improve our children’s health. J Sch Health. 2012;82(5):246–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2012.00694.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang K-Y, Cheng S, Theise R. School Contexts as Social Determinants of Child Health: Current Practices and Implications for Future Public Health Practice. Public Health Rep. 2013;128(Suppl 3):21–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Berliner DC. Poverty and Potential: Out-of-School Factors and School Success. Published online March 9, 2009. Accessed October 27, 2020. https://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/poverty-and-potential

- 52.Gordon MS, Cui M. The Intersection of Race and Community Poverty and Its Effects on Adolescents’ Academic Achievement. Youth & Society. 2018;50(7):947–965. doi: 10.1177/0044118X16646590 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McConnell R, Islam T, Shankardass K, et al. Childhood incident asthma and traffic-related air pollution at home and school. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(7):1021–1026. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pastor M, Morello‐Frosch R, Sadd JL. Breathless: Schools, Air Toxics, and Environmental Justice in California. Policy Studies Journal. 2006;34(3):337–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0072.2006.00176.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pastor M, Sadd JL, Morello-Frosch R. Who’s Minding the Kids? Pollution, Public Schools, and Environmental Justice in Los Angeles. Social Science Quarterly. 2002;83(1):263–280. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hopson LM, Lee E. Mitigating the effect of family poverty on academic and behavioral outcomes: The role of school climate in middle and high school. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011;33(11):2221–2229. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.07.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scott D, Lee KJJ. People of Color and Their Constraints to National Parks Visitation. The George Wright Forum. 2018;35(1):73–82. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Floyd DM. Race, Ethnicity and Use of the National Park System. All US Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository) 1999;(Paper 427):24.

- 59.Rigolon A, Browning M, Jennings V. Inequities in quality urban park systems: An environmental justice investigation of cities in the United States. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2018;178:156–169. [Google Scholar]

- 60.McCown RS. Evaluation of National Park Service 21st Century Relevancy Initiatives: Case Studies Addressing Racial and Ethnic Diversity in the National Park Service Published online 2013. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/220/

- 61.OPINION: Why America’s national parks are so white. Accessed October 29, 2020. http://america.aljazeera.com/opinions/2015/7/heres-why-americas-national-parks-are-so-white.html

- 62.McCormick R. Does Access to Green Space Impact the Mental Well-being of Children: A Systematic Review. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2017;37:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2017.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reuben A, Rutherford G, James J, Razani N. Association of neighborhood parks with child health in the United States. Prev Med. Published online October 6, 2020:106265. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vanaken G-J, Danckaerts M. Impact of Green Space Exposure on Children’s and Adolescents’ Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(12). doi: 10.3390/ijerph15122668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Arango T, Mollenkof B. ‘Turn Off the Sunshine’: Why Shade Is a Mark of Privilege in Los Angeles. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/01/us/los-angeles-shade-climate-change.html. Published December 1, 2019. Accessed February 4, 2021.

- 66.Plumer B, Popovich N, Palmer B. How Decades of Racist Housing Policy Left Neighborhoods Sweltering. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/08/24/climate/racism-redlining-cities-global-warming.html. Published August 31, 2020. Accessed February 4, 2021.

- 67.Washington HA. A Terrible Thing to Waste: Environmental Racism and Its Assault on the American Mind. Illustrated edition. Little, Brown Spark; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 68.The EITC and minimum wage work together to reduce poverty and raise incomes. Economic Policy Institute. Accessed October 29, 2020. https://www.epi.org/publication/eitc-and-minimum-wage-work-together/ [Google Scholar]

- 69.admin. Ending Child Poverty Now: Local Approaches for California. Children’s Defense Fund – California. Accessed October 29, 2020. https://cdfca.org/reports/ending-child-poverty-now-local/ [Google Scholar]

- 70.Coates S by T-N. The Case for Reparations. The Atlantic. Accessed October 29, 2020. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/

- 71.Reducing Racial Disparity in the Criminal Justice System: A manual for Practitioners and Policymakers. The Sentencing Project Research and Advocacy for Reform. Accessed October 30, 2020. https://www.racialequitytools.org/resourcefiles/sentencing.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 72.Top Trends in State Criminal Justice Reform, 2019. The Sentencing Project. Accessed October 30, 2020. https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/top-trends-in-state-criminal-justice-reform-2019/ [Google Scholar]

- 73.Initiative PP, Wagner WSP. Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2020. Accessed November 12, 2020. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2020.html

- 74.Initiative PP. How race impacts who is detained pretrial. Accessed March 5, 2021. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2019/10/09/pretrial_race/

- 75.Jindal M, Heard-Garris N, Empey A, Perrin EC, Zuckerman KE, Johnson TJ. Getting “Our House” in Order: Re-building Academic Pediatrics by Dismantling the Anti-Black Racist Foundation. Acad Pediatr. Published online September 3, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2020.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]