Editor's Note: If you wish to delight in the motion of a hinge on which the medical paradigm is shifting, read this invited commentary from Helene Langevin, MD, the director of the NIH National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH). The receipt of her description of this change led me to seek the perspective of one of Langevin's predecessors, former NIH Office of Alternative Medicine director Wayne Jonas, MD, JACM's Methods Editor. Jonas' response, approved for sharing, began this way: “First of all let me say it is a breath of fresh air to hear Helene's talks recently and the direction of the NCCIH strategic plan on whole person care and the encapsulation of her vision in this essay. Congratulations to her and the whole field for moving the core concepts of integrative health more to central stage not only at NCCIH but also to align it with NIH and our health care system in general in ways that have not happened before.” The direction follows the NCCIH's emphasis on solid methodological foundations over the past decade. Other hinges toward whole person health are also swinging: most prominently, the “whole health” program at the Veteran's Administration; a Whole Health Institute and an associated Whole Health Medical School, with powerful philanthropic backing; and an integrative leader in Indiana's University Hospitals named the network's “Chief Whole Health Officer.” We are fully aligned here at JACM. In January 2022, the journal's subtitle will announce this mission: Advancing Whole Health. Langevin's direction at NCCIH followed an extensive community process, including those talks Jonas' referenced, which led to the NCCIH Strategic Plan 2021–2025: Mapping a Pathway to Research on Whole Person Health. Enjoy Langevin's piece on how she and they arrived at this direction. We are proud at JACM to be helping this cause-of-causes by helping hoist this momentous work into the peer-reviewed world. “Fresh air” indeed!—John Weeks, Contributing Editor, Special Projects and Collaborations, JACM (johnweeks-integrator.com).

Helene M. Langevin, MD

Introduction

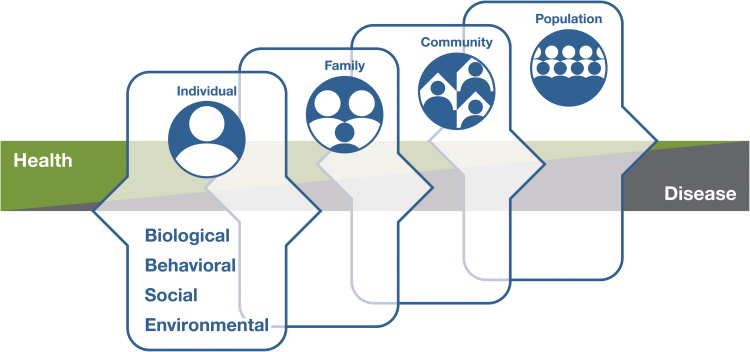

In the face of converging global health crises, the role of the research community in improving people's lives has never been more clear and urgent: the global COVID-19 pandemic, the obesity epidemic, the opioid crisis, and other growing health burdens are loudly telling us that we must think about health in a different way to chart much-needed progress. We must first recognize that these problems are not independent of one another, and then bring the concept of whole person health into discussions of how we are asking and answering pressing research questions. In our work at the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), we understand whole person health to mean supporting the health and well-being of each person across multiple domains—biological, behavioral, social, and environmental—through research on multicomponent nutritional, psychological, and physical approaches to care.

As director of NCCIH, it has been gratifying for me to work with colleagues across NIH who also recognize this imperative and are embracing the concept of whole person health, as we envision it, to inform the critical work of driving discovery. At NCCIH, we have folded the concept of whole person health into our new strategic plan,* which will serve to guide NCCIH's research endeavors for the coming 5 years.

Pragmatic Roots of Whole Person Health

The mindset for whole person health is borne out of the pragmatic challenges we see every day in the experiences of patients and the stubbornly persistent and interconnected factors that can lead people into a poor state of health—and keep them there. The current health crises have galvanized us to better understand the importance of the environment as a determinant of health. This means both the physical environment where people live—housing, air quality, noise and crowding, and food access—as well as the social environment—violence and crime, equity, and justice.

Importantly, we need to consider how these factors act synergistically to impact stress, sleep, and mental health, as well as cardiovascular, respiratory, digestive, endocrine, and immune function. Also, we need to determine the research gaps and identify research opportunities related to behavioral, social, and environmental factors that can be protective and restorative. Implementation research could be especially useful in areas where an evidence base already exists, for example, how access to healthy food and nutrition education influences obesity and metabolic function; how aspects of the physical environment such as access to sidewalks and safe bike paths can influence physical activity and musculoskeletal function; and how access to yoga classes and green spaces can help with stress management.

This is why the concept of whole person health is so important right now. We need to transform our approach to health care through recognition of our interdependence with each other and with the natural world. Our alarming health outcomes, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the global threat of climate change are a call to action to embrace a change in thinking that has already occurred in other areas of science.

The concept of whole person health is an important part of a growing awareness and integrative movement that began in the early 20th century with quantum physics and the birth of ecology, gathered steam in the 1970s with systems biology and network science, and arose expressly in medicine in the 1990s. This way of thinking emphasizes relationships and connections and teaches us that in a system, the whole influences every part, and every part influences the whole. This worldview is not new, and it shares many insights with Eastern philosophies that are foundational to “mind and body” practices such as meditation, yoga, and acupuncture, as well as traditional cultures from around the world that are rooted in awareness of the relationship of humans with nature, as well as the connections between body, mind, and spirit.

From Analysis and Reduction to Synthesis

Throughout the 20th century, biomedical research was strongly pulled toward analysis, the process by which research areas are broken down into smaller and smaller components, from physiological systems to singular molecular pathways. In contrast, synthesis—or the process of bringing components together—requires a different kind of effort that can be challenging, and has lagged behind. Our reductionist mindset translates into clinical settings and the health care that patients encounter. Health care providers are frequently siloed and pathways to care are disjointed, failing to assess the big picture for patients seeking solutions to pressing health problems. The promise of pharmaceutical approaches often becomes a fragile balancing act when multiple conditions—and multiple drugs with the potential for conflicting effects—are present in an individual.

While there are many causal factors, a fragmented approach that treats diseases one at a time, as though they are independent of each other, feeds our nation's overall poor state of health. In fact, more than a quarter of Americans were reported to have more than one chronic condition by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Center for Health Statistics in 2018.1 The presence of multiple chronic conditions—such as obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and degenerative joint disease—is often associated with other health burdens such as chronic pain, chronic stress, depression, opioid addiction, and suicide.

The toll of these health burdens can be seen in our nation's declining life expectancy. Although life expectancy at birth increased consistently over time in the United States through 2014, we saw a pivot in 2015 into consecutive years of decline.2 This downward trend may reflect a quantitatively small loss of life years, but our failure as a nation to make gains over those years is alarming.

The domino effect of chronic conditions is seen in the disproportionate toll they take on black, Hispanic, and other communities that are often both challenged by harmful social and environmental factors and underserved in our medical delivery ecosystem. For example, although COVID-19 is a respiratory infection, underlying chronic conditions have proven to be important factors in the severity and mortality of this disease, and, compounded by socioeconomic factors, serve to exacerbate the burden of COVID-19 in vulnerable populations. This pattern of disparities is visible in many other conditions.

In short, viewing human health through the prism of pieces and parts is no longer tenable. Scientific inquiry is vital to medical breakthroughs in diagnosing, treating, and preventing specific diseases. But alone, it is not enough. Our state of poor health creates an urgent need to “reassemble” the pieces and parts of health and see the whole person.

The Bidirectional Continuum of Health and Disease

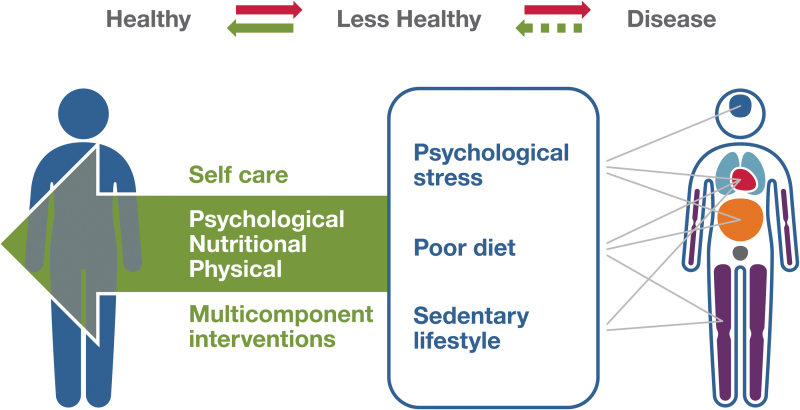

To understand whole person health, it is also essential to recognize the bidirectional continuum between health and disease on which people are always traveling (Fig. 1). In doing so, we can deepen not just our understanding of disease prevention, but also health restoration—or salutogenesis. This would include, for example, the return to health after an acute viral illness or flare-up of a chronic condition; normalization of cholesterol, hemoglobin A1C, and/or blood pressure in a patient with metabolic syndrome through lifestyle modification; and return to function and mobility after a musculoskeletal injury. We do not know whether salutogenesis consists of “pathogenesis in reverse,” or whether specific salutogenic mechanisms need to be activated for health to be restored.

Fig. 1.

Bi-directional health-disease continuum.

Within this framework, we can gain a necessary vantage point for looking at connections across biological, behavioral, social, and environmental domains, to better understand how co-occurring conditions arise and how protective factors can promote and restore health. We know that living organisms are organized into multiscale interdependent networks that not only can self-organize, but also have the potential to evolve and “grow” through the emergence of patterns of higher complexity in response to challenges. This can happen from the “bottom-up”—immune responses, epigenetic changes, or microbiome adaptations—or the “top-down”—changes in behavior or societal changes. It is important to point out that whole person research is not simply studying all the components of the whole person, but also exploring connections between these components such as “balance” and “adaptability” that relate to complex system behaviors.

The framework for understanding whole person health gives us the opportunity to examine the potential role of multicomponent interventions, building on NCCIH's current research portfolio on nutritional, psychological, and physical treatment approaches. For the research community, the whole person health framework serves as a way to explore the potential for interventions developed with the whole person in mind to impact several systems, improving overall health.

In fact, whole person health has already taken root across NIH, and NCCIH has been proud to lead and collaborate on research initiatives such as Bridge to Artificial Intelligence,† Sound Health,‡ the Health Care Systems Research Collaboratory,§ and others. Each of these projects involves Institutes and Centers across NIH and reflects the growing recognition that an integrative mindset has the potential to have a transformative impact on research. The NCCIH team is proud that these collaborations put our center in a position to serve as a convener for important discussions and collaborations that can accelerate progress in this area.

Another important area of activity and leadership has come from The Veterans Health Administration's Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Collaboration through its “Whole Health” program. Evaluating whole person care models—including long-term outcomes, cost-effectiveness, and care across various health care settings—is important to ensuring that proven approaches can eventually be adopted into care. Robust evidence supporting whole person approaches can lead to inclusion within health coverage, making care accessible, including for socioeconomically disadvantaged populations.

Complexity of Research on Whole Person Health

While the opportunity to deepen the work in whole person health research is clear, we recognize that studies on this topic will be challenging. By nature, whole person health is complex. At NCCIH, we see opportunities to foster discussion on addressing complex methodologies required for studies, support peer reviewers in effectively evaluating studies that take a whole person approach, and promote enhanced cross-disciplinary collaboration. It will take coordinated effort among stakeholders in the research community to explore both the challenges and the opportunities.

To advance research on whole person health and rigorous studies that generate meaningful results, we must develop innovative approaches for overcoming specific hurdles. Research on whole person health must integrate across physiological systems, explore multicomponent interventions, and measure the impact of interventions in multiple organs, systems, and domains. We must also advance our ability to measure outcomes of interest. As researchers, we are well equipped to measure negative outcomes such as pain or processes such as inflammation. But we are less grounded in how to measure positive outcomes such as resilience or stamina or mechanisms such as regeneration or repair.

One area of exploration is that of multicomponent approaches, which can include therapeutic systems such as Traditional Chinese Medicine, Ayurveda, and naturopathy that have underlying theoretical diagnostic and therapeutic frameworks that are different from those of conventional medicine. This type of research is challenging to conduct, and early studies supported by NCCIH were hampered by challenges in finding the right methods for studying complex interventions. But methods subsequently derived from NCCIH's work, particularly those focused on testing interventions that have demonstrated efficacy within pragmatic clinical trials, will serve as a helpful roadmap in advancing research into multicomponent approaches.

The field of nutrition research illustrates both the opportunity and the challenges that come with research on whole person health. Establishing new approaches to thinking about health and health restoration opens new doors within the nutritional domain, encompassing facets such as probiotics, prebiotics, herbs, vitamins and minerals, other essential nutrients, food as medicine, metabolites, and dietary patterns. Research in this area can deepen what we understand about the role of nutrition within multicomponent approaches, whether they are conventionally based programs or rooted in systems outside of conventional medicine. We will also gain more understanding of multicomponent practices in wide use today through diverse sets of integrative practitioners, and individuals in their self-designed care.

Stress management research is another area where a whole person health approach will potentially be transformative. Stress is often perceived as occurring in the mind, but it has well-documented physical effects as well. We know that chronic stress can negatively influence physiological processes involving every aspect of the body. Research on stress management using “mind and body” approaches such as meditation and yoga so far has mostly focused on psychology and neuroscience, but there are tremendous opportunities to integrate mind and body and explore how stress management can impact extra-neural systems as well, including the endocrine, immune, digestive, cardiovascular, and musculoskeletal systems.

A Clear Imperative for Whole Person Health

Our nation's current poor state of health highlights the urgency of addressing the lack of integration in health care. I do not expect the effort to be easy. Reductionist approaches are hardwired into much of how we think about research. But for those in the research community who see the opportunity that comes with examining research questions through a whole person health framework, our newly published strategic plan will provide important guideposts.

By incorporating strong methodology, multisystem interactions, health restoration, resilience, and patient engagement, I am confident that NCCIH-supported research will yield new insights and change health care for the better: not just make health care patient centered but make it centered on the whole person.

Integrative health is not simply putting complementary and conventional medicine together. It is an emergent field of study that aims at transforming health care through a balance of analysis and synthesis, a focus on health, and an understanding of the fundamental interconnectedness of human life with its environment—both the social determinants of health as well as the physical environment.

When fully realized, integrative health is whole person health: empowering individuals, families, communities, and populations to improve their health in multiple interconnected domains: biological, behavioral, social, and environmental (Fig. 2). This will be challenging but well worth the effort.

Fig. 2.

Multi-level whole person health framework.

NCCIH Strategic Plan FY 2021–2025: Mapping a Pathway to Research on Whole Person Health (https://www.nccih.nih.gov/about/nccih-strategic-plan-2021-2025).

Bridge to Artificial Intelligence (https://commonfund.nih.gov/bridge2ai).

Sound Health: An NIH-Kennedy Center Partnership (https://www.nih.gov/research-training/medical-research-initiatives/sound-health).

NIH Health Care Systems (HCS) Research Collaboratory (https://commonfund.nih.gov/hcscollaboratory).

References

- 1. Boersma P, Black LI, Ward BW. Prevalence of multiple chronic conditions among US adults, 2018. Prev Chronic Dis 2020;17:E106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Woolf SH, Schoomaker H. Life expectancy and mortality rates in the United States, 1959–2017. JAMA 2019;322:1996–2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]