Introduction:

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has affected millions of people worldwide and is caused by infection from the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 pathogen. While COVID-19 most commonly affects the respiratory system, multiple neurological complications have been associated with this pathogen. We report a case of Wernicke encephalopathy in a young girl with poor oral intake secondary to anosmia and dysgeusia after a COVID-19 infection.

Case Report:

After a recent infection of COVID-19, a 15-year-old girl developed an overwhelming noxious metallic tase resulting in a 30 lb weight loss from being unable to tolerate oral foods. She presented to the hospital 3 months later with bilateral horizontal conjugate gaze palsies, up beating vertical nystagmus, difficulty with limb coordination and gait ataxia. She was found to have a thiamine level of 51 nmol/L (reference range: 70 to 180 nmol/L) and her brain magnetic resonance imaging showed fluid-attenuated inversion recovery and diffusion-weighted imaging changes in the periaqueductal gray and dorsomedial thalami suggestive of Wernicke encephalopathy. She was started on parenteral thiamine replacement and had significant neurological improvement.

Conclusions:

As this pandemic continues to progress, more long-term neurological sequelae from COVID-19 such as Wernicke encephalopathy can be expected. Strong clinical suspicion for these complications is needed to allow for earlier diagnosis and faster treatment initiation.

Key Words: COVID-19, syndrome coronavirus-2, thiamine deficiency, Wernicke encephalopathy, vitamin deficiency

CASE REPORT

A previously healthy 15-year-old girl presented to the emergency department with 1 week of abnormal eye movements, horizontal diplopia and gait instability. Three months prior, she developed rhinorrhea, cough, and subjective fevers after a family member living in the same house was diagnosed with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Over the next few weeks she developed anosmia and dysgeusia and was unable to tolerate oral intake of food due to an overwhelming noxious metallic taste causing severe nausea and occasional emesis. She had multiple emergency department visits during this time for nausea and reported an ~30 pound weight loss. One week before her hospitalization, she began to notice “swaying” of the world around her, horizontal diplopia and unsteadiness while ambulating. These symptoms gradually worsened resulting in her becoming bed bound due to unsteady gait.

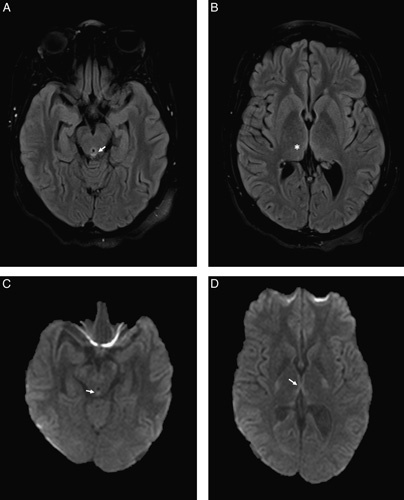

On admission, she was found to have bilateral horizontal conjugate gaze palsies, up beating vertical nystagmus, difficulty with limb coordination and gait ataxia. She had complete loss of smell to ground coffee, sweet scented soap, and peanut butter as well as a strong metallic taste to salty crackers, sweet cereal, and sour candy. Her syndrome coronavirus-2 antibody testing was positive. She was found to have thiamine deficiency [51 nmol/L (reference range: 70 to 180 nmol/L)] and was diagnosed with Wernicke encephalopathy. Her brain magnetic resonance imaging revealed typical findings of thiamine deficiency with fluid-attenuated inversion recovery and diffusion-weighted imaging changes in the periaqueductal gray and dorsomedial thalami (Fig. 1). She was also found to have folate deficiency (3.8, normal ≥5.9 ng/mL), low albumin (3.0, normal: 3.5 to 4.9 g/dL), and vitamin C deficiency (<5, normal: 23 to 114 μmol/L) and weighed 67 kg (down from a reported 85 kg 3 mo prior), further suggestive of severe malnutrition. She was started on parenteral thiamine replacement with great improvement after 1 week and was discharged home with oral vitamin supplementation and physical therapy.

FIGURE 1.

MRI brain revealed findings suggestive of Wernicke encephalopathy with hyperintense lesions on FLAIR sequences in the periaqueductal gray and dorsomedial thalami (A, B) and restricted diffusion on DWI sequences in the periaqueductal gray and around the third ventricle (C, D). The white arrows illustrate the changes in the periaqueductal gray area and the star illustrates the changes in the dorsomedial thalami seen in Wernicke Encephalopathy on MRI. DWI indicates diffusion-weighted imaging; FLAIR, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

DISCUSSION

We report a case of Wernicke encephalopathy in a young girl after a recent antibody confirmed COVID-19 infection. She had hallmark signs of Wernicke encephalopathy with nystagmus, bilateral horizontal gaze ophthalmoplegia and gait ataxia. While altered mental status is a core symptom of Wernicke encephalopathy, only 16% have all 3 core triad symptoms of encephalopathy, ophthalmoplegia and ataxia.1 In addition, younger patients who develop Wernicke encephalopathy are thought to be at less risk for encephalopathy due to an increased cognitive reserve.2 The presumed cause of our patient’s Wernicke encephalopathy is severe malnutrition secondary to olfactory and gustatory dysfunction from her recent COVID-19 infection, resulting in thiamine deficiency. This is the most likely cause, as she did not have other risk factors for thiamine deficiency such as alcohol usage, personal dietary restrictions, eating disorder or other medical causes of malabsorption. In addition, our patient developed symptoms of thiamine deficiency ~2 months after onset of anosmia and dysgeusia which is similar to the 4 to 12 week time course observed in bariatric surgery patients who develop Wernicke encephalopathy.3

Olfactory and gustatory dysfunction are common early onset neurological complications of COVID-19. A meta-analysis of reported studies demonstrated a 52.7% prevalence of olfactory dysfunction (ranging from hyposmia to anosmia) and 43.9% prevalence of gustatory dysfunction (ranging from hypogeusia to dysgeusia).4 The duration of these symptoms is unclear and further outcome studies are needed, especially in patients with severe olfactory and gustatory dysfunction. Of the limited studies to date, the median time to recovery for both hyposmia and dysgeusia is 7 to 17 days, but some case reports have failed to show improvement >1 month after infection.5–8

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to progress, there will be more patients at risk for late onset COVID related complications. These patients will be at risk for different neurological complications than those seen in the earlier stages postinfection. Vitamin deficiencies such as thiamine deficiency are a serious concern, especially in patients experiencing severe olfactory and gustatory dysfunction. Strong clinical suspicion for these complications is needed to allow for earlier diagnosis and faster treatment initiation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

David Ross Landzberg, Email: David.Ross.Landzberg@Emory.Edu.

Ekta Bery, Email: ekta.indra.bery@emory.edu.

Suhasini Chico, Email: suhasini.padhi@emory.edu.

Sookyong Koh, Email: sookyong.koh@emory.edu.

Barbara Weissman, Email: bweissm@emory.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1. Harper CG, Giles M, Finlay-Jones R. Clinical signs in the Wernicke-Korsakoff complex: a retrospective analysis of 131 cases diagnosed at necropsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1986;49:341–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Oudman E, Wijnia JW, van Dam M, et al. Preventing Wernicke encephalopathy after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2018;28:2060–2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Singh S, Kumar A. Wernicke encephalopathy after obesity surgery: a systematic review. Neurology. 2007;68:807–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tong JY, Wong A, Zhu D, et al. The prevalence of olfactory and gustatory dysfunction in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163:3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lee Y, Min P, Lee S, et al. Prevalence and duration of acute loss of smell or taste in COVID-19 patients. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:e174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Paolo G. Does COVID-19 cause permanent damage to olfactory and gustatory function? Med Hypotheses. 2020;143:110086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kosugi EM, Lavinsky J, Romano FR, et al. Incomplete and late recovery of sudden olfactory dysfunction in COVID-19. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;86:490–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hopkins C, Surda P, Whitehead E, et al. Early recovery following new onset anosmia during the COVID-19 pandemic-an observational cohort study. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;49:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]